Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common, early-onset and enduring developmental disorder whose underlying etiological and neurobiological processes are the current focus of major research. Research strategies have made considerable effort in elucidating the complex genetic architecture of ADHD and indicate various pathways from genotype to phenotype. Understanding ADHD as a neuropsychiatric disorder enabled to investigate markers of neural activity as endophenotypes to better explain the link from gene to symptomatology (the so-called imaging genetics approach). Overcoming the originally rather restrictive requirements for an endophenotype, imaging genetics studies are supposed to offer a much more flexible and hypothesis-driven approach towards the etiology of ADHD. Although 1) ADHD often persists into adulthood, thus remaining a prevalent disorder, and 2) imaging genetics provides a promising research approach, a review on imaging genetics in adult ADHD – as available for childhood ADHD (Durston 2010) – is lacking. In this review, therefore, findings from the few available imaging genetics studies in adult ADHD will be summarized and complemented by relevant findings from healthy controls and children with ADHD that are considered important for the adult ADHD imaging genetics approach. The studies will be reviewed regarding implications for basic research and possible practical applications. Imaging genetics studies in adult ADHD have the potential to further clarify pathophysiological pathways and mechanisms, to derive new testable hypotheses, to investigate genetic interaction effects and to partly influence practical applications. In combination with other research strategies, they can incrementally foster the understanding of relevant processes in a more comprehensive way. Current limitations comprise the incapability to discover new genes, a high genetic load in patients potentially obscuring the effect of single candidate genes, the mostly unknown heritability of the endophenotype and the heterogeneous manifestation of ADHD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) represents a common, early-onset and enduring neurodevelopmental disorder with a worldwide-pooled prevalence of 5.3% in childhood and adolescence [1]. In adulthood, ADHD-related symptoms may still cause impairments and its pooled prevalence still amounts to 2.5% [2, 3], so it cannot be regarded a mere transitional childhood disorder. Both childhood and adult ADHD have a large economic impact on society [4] and have been in a major focus of research in the last decades (see [5, 6]).

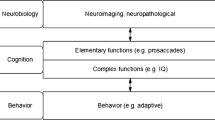

Research strategies have made great efforts in elucidating the complex genetic architecture of childhood and adult ADHD [7, 8]; association and linkage studies have revealed relationships of specific candidate genes with ADHD and with disorder-specific symptom scales, pointing towards pathophysiologically relevant genetic influences. The understanding of ADHD as a neuropsychiatric disorder (e.g., [9]) further enabled the investigation of the influence of specific genetic variations on markers of neural activity to better explain the link from gene to disorder and symptoms, respectively [10]. In such an imaging genetics approach neuroimaging data are treated as endophenotypes [10, 11], which are assumed to be more closely related to the underlying cellular and pathophysiological processes than the symptomatic behavior or the categorical diagnoses themselves. The pathway from gene to behavior is complex and characterized by different steps (see Figure one in [12]): variation in gene expression results in differential availability of proteins, which are necessary for specific structural and functional properties of neurons that make up neural units and circuits. The response of these circuits can be measured using various neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), magnetoencephalography (MEG) and electroencephalography (EEG). The first imaging genetics studies were published around the millennium (e.g., [13]) when imaging methods became more broadly available. Since then, the number of publications on imaging genetics has increased considerably and studies where applied to various neuropsychiatric disorders and related (endo)phenotypes.

Although the endophenotype concept for neuropsychiatric disorders [14] was rather restrictive and axiomatic when being first introduced (e.g., [11]), in recent years notions for a reconceptualization have been proposed. For example, Kendler and Neale [15] stress the necessity of differentiating between mediational (i.e. the endophenotype mediates the relation from gene to disorder) and liability index models (i.e. the endophenotype is risk-indicating and may only be an epiphenomenon), thus broadening the original framework. Furthermore, endophenotypes and thus imaging data could reflect environmental influences; it is also feasible to assume that some genetic influences only affect the endophenotype while others only affect the clinical symptoms [15]. Taken together, this illustrates that current concepts of (neuroimaging) endophenotypes may provide new insights into the pathophysiological processes and mechanisms as several influencing factors are considered and as the originally rather restrictive requirements for an endophenotype do not have to be fulfilled. This allows a much more flexible and hypothesis-driven approach towards the etiology of ADHD. Yet, imaging genetics in ADHD is still in its infancy and studies are scarce [16].

Although 1) ADHD often persists into adulthood, thus remaining a prevalent disorder, and 2) imaging genetics provides a promising research approach, a review on imaging genetics in adult ADHD – as available for childhood ADHD [17] – is lacking. In the present review, we will first summarize the findings from the few available imaging genetics studies in adult ADHD and subsequently discuss the various potentials and challenges in pathophysiological research and clinical implications assuming a more flexible understanding of endophenotypes [15].

Review

Literature searches using available data bases (pubmed, google scholar) were conducted to find imaging genetics studies in adult samples of ADHD (till May 2013). Eight studies (4 fMRI, 4 EEG) were then classified into two categories, i.e. cognitive and affective-motivational approaches, depending on whether they applied cognitive or emotional-motivational paradigms.a Although this distinction is arbitrary and may not always be unambiguous, it should help to better organize the available data. Table 1 summarizes the reviewed studies and Table 2 provides information about the effects the gene variants have.

Cognitive paradigms

Patients with childhood and adult ADHD show impairments in different cognitive domains [18, 19] which represent a core feature in ADHD-related psychopathology (e.g., [5]). The available imaging genetics studies have implemented different cognitive paradigms.

Go/NoGo paradigms

Continuous performance tasks (CPT, see [20]) involve the combination of response execution (in Go trials) and response inhibition processes (in NoGo trials) and thus higher-order motor control and attention. In a series of electroencephalographic (EEG) studies, our research group has applied an OX version of the CPT in a large sample of adult ADHD patients investigating the influence of several gene variants on behavioural and neural parameters. In these studies, we derived a topographical event-related potential (ERP) parameter, the so-called NoGo anteriorization (NGA), which has been proposed to reflect mechanisms of prefrontal response control. Basically, the individual NGA is calculated as the difference between the mean area centroids of the P300 field maps for the Go and NoGo condition. In one study [21], for two ADHD-associated gene variants within the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) gene (i.e. rs4570625, rs11178997) the risk alleles were associated with reduced NGA in both patients and controls. On the behavioral level, the expected pattern of lower performance in ADHD was found. In a subsequent study, the dopamine transporter (DAT, SLC6A3) gene was investigated. It had been found that in adult ADHD – contrary to childhood ADHD – the 9-repeat allelic variant of SLC6A3 represented the risk allele [22, 23]. Therefore, we hypothesized for our adult sample that the 9-repeat allele should be associated with decreased prefrontal function. In line with this hypothesis we found that – only in patients – the 9-repeat allele was associated with a reduced NGA, while there was no significant effect in the control group [24]. Recently, we were able to show that – across ADHD patients and controls – there was no main effect of two common gene variations (i.e. catecholamine-O-methyl transferase [COMT] val158met polymorphism; dopamine receptor D4, DRD4 variable number of tandem repeats [VNTR]) on behavioral performance or the NGA, but an interaction between the gene variants on the investigated parameters [25]. Such gene-by-gene interaction effects may offer new insights into the interplay of various genes at the physiological level. During the last years, a rather unexpected genetic candidate came into focus of ADHD research, i.e. common haplotype of the latrophilin 3 (LPHN3) gene that has been found to be associated with the disorder in pedigrees and population-based studies [26, 27]. It has also been shown to modulate dopaminergic neuron formation and locomotor activity/impulsivity in zebrafish, whereby effects can be influenced by methylphenidate [28]. Given this, we also found that having two risk alleles of the LPHN3 gene was associated with a decreased NGA [29].

Working memory paradigms

In these tasks, subjects are required to maintain or manipulate information in memory to fulfil specific experimental conditions. In an fMRI study, Brown et al. [23] applied a sequential letter visual n-back task and investigated whether task-specific activation contrasting 2- vs. 0-back was influenced by group or DAT genotype. While no differences emerged on the behavioral level, a marginal association of the DAT 9-allele with increased task-related suppression in the left medial PFC and a marginal genotype × diagnosis interaction in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) was found. According to the authors, the finding suggests that the task-related suppression in the default mode network (DMN) might act as an intermediate phenotype between DAT1 and ADHD.

Interference paradigms

These tasks require subjects to ignore specific (task-irrelevant) information to perform the experimental conditions correctly. In an ADHD group, Brown et al. [30] investigated mediating effects of the DAT1 gene on dACC function in a multi-source interference task (MSIT) and found less activation in homozygous 10- as compared to 9-repeat allele carriers when confronted with response-incongruent interfering stimuli.

Affective-motivational paradigms

In the emotional domain, ADHD patients also display various disturbances [31]; however, these have so far rarely been investigated in imaging genetics studies.

Reward paradigms

Hoogman et al. [32] applied a delay discounting task in which subjects had to choose between hypothetical immediate or delayed rewards. fMRI data indicated a generally increased ventral striatal activity in controls vs. ADHD patients; however, across both groups homozygous carriers of the short allele of the nitric oxide synthase (NOS1) gene (for more information see [33]) exhibited increased activity which – in the patients – was accompanied by higher impulsivity. Therefore, the authors assume the NOS1 influence on ADHD to be mediated by its effect on impulsivity. In another study, Hoogman et al. [34] investigated the influence of a DAT haplotype on ventral striatum activation during reward anticipation. Here, besides the a priori expected increased ventral striatal activity in controls vs. ADHD patients, no effect of the haplotype could be discerned.

Paloyelis et al. [35] argued against a deficit in anticipation-related neural activation in the ventral striatum. Instead they suggested dysfunctional processing of reward outcomes in adolescents with combined ADHD subtype (ADHS-CT). They further highlighted the role of genes influencing dopamine signaling in reward-processing as a DAT haplotype was found to modulate striatal responsivity during incentive-predicting stimuli. DAT 10/6-repeat allele homozygosity was associated with decreased reward-related anticipatory striatum activity in the ADHD-CT on the one hand, but increased neural activation in healthy controls on the other hand. In how far these findings also apply to adults has yet to be investigated.

Research on other endophenotypes and genes

As the number of available imaging genetics studies in adult ADHD is limited so far, we will shortly refer to exemplary findings in healthy subjects and children. Especially studies on emotional processing are promising. Behavioral studies reveal that ADHD children are less accurate in classifying emotional facial expressions [36–38]. On some measures they even tend to perform worse than autistic children [39] and seem to be unaware of their compromised social cognition [40]. These perceptual deficits can interfere with executive functions [41] and are not restricted to facial expressions, but occur in a similar way for vocal emotions [36, 37]. Behavioral studies in adult ADHD indicate that deficits in judgment of facial expressions persist to adulthood [31]. The neural correlates of this disturbed perception of emotional signals as well as their genetic origins, however, are largely unknown and warrant further investigation.

Neuroimaging studies in healthy participants provided evidence for distinct pathways for explicit versus implicit processing of emotions in faces [42] and voices [43]. Studies on explicit processing of emotions in childhood ADHD [44] revealed a hyperactivation of the amygdala during such paradigms. This enhanced activation of the amygdala in ADHD patients is in line with structural findings [45] as well as with a reduction of dopamine receptors [46] in this brain area. Genetic imaging studies in healthy subjects demonstrated that brain activation during emotional processing can be strongly influenced by the genotype of key enzymes of dopaminergic pathways including DRD4 [47] and DAT [48]. These genes have been associated with an increased risk for ADHD (for a review see [7, 27]). In particular, the high-activity genotype of COMT is a strong candidate for mediating altered emotional perception in ADHD since it has been shown to be linked to antisocial behavior in this patient group [49]. Similarly, recently described genes such as the brain-expressed GTP-binding RAS-like 2 gene DIRAS2 [50] and LPHN3 [27, 49] have also been shown to be associated with personality traits that predispose to socially disruptive behavior. Further candidate genes derived from imaging genetics studies in healthy adults that might impact perception of emotional stimuli in ADHD include the TPH2, which has been shown to modulate amygdala activity to emotional stimuli (rs4570625 G-allele polymorphism, [51]), as well as Stathmin 1 (STMN1), a neuronal growth associated protein which is highly expressed in the amygdala that modulates the P300 in an emotional Stroop task (rs182455 C-allele, [52]). Considering overlapping symptoms with borderline personality disorder (BPD) [53], studying mechanisms related to emotional dysregulation may clarify shared pathways.

Apart from dysfunctional emotional processes, other endophenotypes need to be considered in further studies, e.g., neuropsychological deficits, such as measures of attention, executive function and processing speed [54]. Furthermore, also other genes in the dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic and neurotrophic system need to be considered [7].

Discussion

So far, imaging genetics studies in adult ADHD are – compared to other lines of ADHD research – rather scarce and research is still at its beginning. Nonetheless, the available findings provide an outlook on the potential chances of this research approach which – in combination with complementary approaches – may help to increase our knowledge about the pathophysiological pathways in adult ADHD. Yet, several limitations need to be considered as well (see below).

Promises

The imaging genetics approach provides an improved insight into possible, important pathophysiological pathways and it allows deriving testable hypotheses that promote a better understanding of the neurobiology of normal and pathophysiologically altered behavior. Studies reporting that gene variants influence neural markers independently of diagnostic status (e.g., [21, 23, 25, 32]) hint at common neural pathways in patients and controls. Such influences are in line with a more continuous model of ADHD phenotypes going beyond simple categorical disorders. Assuming such a continuously distributed trait in the population [55, 56] – with ADHD being defined by an arbitrary threshold on this trait – may allow to estimate the individual risk for passing this threshold taking into account several single candidate genes. Studies only showing associations in ADHD patients, but not in healthy controls (e.g., [24]), hint at more disorder-specific pathways that may influence brain activity – and therefore clinically relevant behavior – independently of shared processes. Here, the presence of specific gene variants may indicate specific (neuropsychological) symptom dimensions, e.g., neural impairment in executive functions.

Candidate genes that have been replicated empirically in large-scale association studies (e.g., DAT) can be tested regarding their functional impact in a hypothesis-driven approach. These genetic findings indicate an involvement of specific psychopathological pathways which can be further investigated in imaging genetics studies: For example, the association of the DAT 9-repeat allele with adult ADHD led to our hypothesis that this allele – which influences the frontal-striatal loop – may be associated with a concurrent less efficient prefrontal functioning in our adult ADHD sample [24].

Imaging genetics has the potential to be used in a translational manner, thus allowing basic findings to influence practical applications. If specific gene variants are highly associated with altered brain activation in specific cognitive or emotional domains, a more tailored pharmacological or psychotherapeutic intervention can be chosen, thus offering new treatment targets [57]. Mattay et al. [58] found that COMT val/val carriers (i.e. carriers of the high enzyme activity variant putatively showing suboptimal prefrontal function at baseline) displayed more efficient prefrontal function in a working memory task after an amphetamine challenge, whereas in met/met carriers counterproductive effects were observed at high working memory loads. Studying schizophrenic patients, Ehlis et al. [59] found the val/val allele to be associated with lower performance and a reduced NGA; furthermore, they showed that patients responded better to typical or atypical antipsychotics depending on their NGA values before treatment [60]. Using and combining such knowledge may help to more carefully adjust treatment regimes and to reduce side effects.

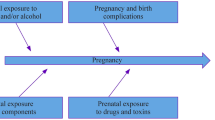

Complex interactive effects of several genes with individually small impact [61] have been suggested to underlie ADHD. The increasing number of large-scale studies will enable to investigate putative gene-by-gene interactions and their influence on ADHD-related behavior and neurophysiology (e.g., [25]). Beyond, also environmental factors contribute to ADHD; however, little is known about precise gene-by-environment interactions on the neural level. Therefore, gene-by-environment interactions could be a further target in such studies augmenting the data from behavioral studies and helping to clarify existing inconsistencies [62]. Integrating imaging genetics to investigate these interactions (for an overview see [63]) and distinct endophenotypes can lead to more precise statements concerning direct versus indirect effects of genes or environment on ADHD.

Imaging genetics is one element that in combination with other – also distant – research strategies (e.g., in vivo and in vitro investigations, animal models, combined PET-fMRI measurements) helps to identify important pathophysiological mechanisms. For example, the research on the risk haplotype in the LPHN3 gene originated from pedigree linkage studies in a Columbian genetic isolate [26] and was subsequently complemented by association samples in Caucasian samples [27, 64]. This convinced us to stratify our ADHD sample regarding this haplotype and we indeed found a reduced prefrontal functioning in the subgroup with two risk alleles [29]. At the same time, a study investigating the ortholog lphn3.1 in the zebrafish revealed that loss of its function resulted in misplaced diencephalic dopaminergic neurons and hyperactive and impulsive swimming behaviour; furthermore, this could be reversed by the common ADHD drugs methylphenidate and atomoxetine [28]. These findings fit with disturbances in the development of the dopaminergic system being influenced by this protein/receptor complex whose actual function is not well understood. As LPHN3 is not a direct key player in the dopaminergic system, its functional impact has to be further investigated. Here, imaging genetics may help to identify functional processes and underlying brain networks that are affected by gene variants and might link LPHN3 (albeit indirectly) to dopaminergic pathways.

Current limitations of the reviewed studies

Up to now, most studies in imaging genetics, especially in clinical research, lack large sample sizes. Several factors may contribute to this: e.g., patient recruitment problems or financial issues. Moreover, no longitudinal studies investigating the impact of gene variants across a specific time-span are available. Particularly, the different association of DAT polymorphism with ADHD in childhood vs. adulthood should be further elucidated by longitudinal research.

Although these candidate gene studies provide important information in the context of a clear functional hypothesis, they are unable to discover new genes or their combinations [65]. A genome-wide approach could, but is not feasible in imaging genetics. Furthermore, only investigating single genes might be a restricted perspective on the complexity, as larger influences of non-candidate genes could be missed.

The imaging genetics approach might be problematic, as patients are prone to disorder-related confounds and hence carry a high genetic load which also includes low-frequency genes (see Box 7 in [66]). This may obscure the effect of single common candidate genes which are the main target of the articles. The investigation of ADHD genes in larger healthy samples could help to assess and avoid these confounds.

Often, the question remains whether the applied imaging paradigms are in fact heritable. To date, a few studies already indicate heritability of the brain activation during working memory [67, 68] and inhibition [69] which supports the assumption of a heritable endophenotype; however, for most of the paradigms heritability has not been tested.

As dopaminergic candidate genes have been extensively investigated in molecular genetics studies [7, 70], imaging genetics studies should more specifically target these to further elucidate intermediate neurobiological processes.

ADHD shows a considerable overlap in clinical symptoms (e.g., emotional dysregulation) with BPD. High genetic correlations for these disorders support the hypothesis that ADHD in childhood might even be a precursor of BPD in adulthood [71]. Thus, future imaging genetics studies should include patient samples of both disorders to clarify whether identified endophenotypes are specific or reflect a common pathway of these disorders that result in impaired emotion regulation.”

Another aspect which is often not considered in current research literature on ADHD is its rather heterogeneous manifestation. Refining research in this respect might reduce contradictory results and simultaneously enhance comparability between studies. Also in this context, imaging genetics could be one approach to define ADHD subtypes that are more strongly related to differences in underlying neurobiology than current “clinical” diagnostic classifications. Some studies focusing on DSM-IV subtypes (inattentive, hyperactive, combined type) did not provide any significant effects [72, 73], while others revealed age-specific and persistent as well as cross-subtype and subtype-specific gene influences [74]. Such findings highlight the need to control for factors such as age or comorbid symptoms in imaging genetics studies. Beyond that, the so far scarce evidence of a genetic basis for DSM-IV subtypes needs to be further substantiated. Alternatively, besides diagnostic subtypes, further neuropsychologically based models could be taken into account to cope with the heterogeneity in ADHD. For example, the dual pathway model [75], subsequently refined to a triple pathway model [76], suggests ADHD-CT to be either a motivational style or a dysregulation of inhibition which in turn are suggested to be based on different pathways in the dopamine system. Even though current models still differ in many ways and could be further corroborated, they share the notion of ADHD as a heterogeneous disorder including different subtypes based on alterations in distinct neural pathways. This common view should be considered when focusing on gene moderating or mediating effects on brain functioning in ADHD with the longer-term objective to diminish inconclusive or contradictory results.

Limitations of the review

The review is based on only a few studies which prevents drawing strong unequivocal conclusions. These studies are also rather diverse with regards to paradigm, endophenoype measurement and investigated candidate genes.

Conclusion

Taken together, current literature on the genetics of ADHD is not conclusive. Here, imaging genetic studies could come into play and lead to new insights regarding the complex and diverse pathways from the level of genetic vulnerability to overt clinical symptoms. Also, presently, the reported research findings are not directly applicable in clinical practice for adult ADHD (diagnostics, treatment, therapy) which is an aspiration for the near future. As in 30% of ADHD patients stimulant treatments do not lead to symptom improvements [77], further research on pharmacogenetics is required. Longterm-studies integrating neuropsychological and neuroimaging methods may advance our comprehension of underlying mechanisms in drug action. Up till now, only one study has combined functional near-infrared spectroscopy imaging and possibly moderating genotypes in a treatment study using methylphenidate [78]. So, in research on effective and long-term stable treatment, different ADHD subtypes should be taken into account using imaging genetics.

Endnote

aOne study [78] was not integrated as both adult and adolescent ADHD patients were investigated, but not analyzed separately.

References

Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA: The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2007, 164: 942–948. 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.942

Simon V, Czobor P, Balint S, Meszaros A, Bitter I: Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2009, 194: 204–211. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048827

Faraone SV, Biederman J: What is the prevalence of adult ADHD? Results of a population screen of 966 adults. J Atten Disord 2005, 9: 384–391. 10.1177/1087054705281478

Matza LS, Paramore C, Prasad M: A review of the economic burden of ADHD. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2005, 3: 5. 10.1186/1478-7547-3-5

Barkley R: Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. 2nd edition. New York: Guilford; 1998.

Biederman J: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a selective overview. Biol Psychiatry 2005, 57: 1215–1220. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.020

Franke B, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Bau CH, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Mick E, Grevet EH, Johansson S, Haavik J, Lesch KP, Cormand B, Reif A, International Multicentre persistent ADHD Collaboration: The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review. Mol Psychiatry 2012, 17: 960–987. 10.1038/mp.2011.138

Khan SA, Faraone SV: The genetics of ADHD: a literature review of 2005. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2006, 8: 393–397. 10.1007/s11920-006-0042-y

Durston S: A review of the biological bases of ADHD: what have we learned from imaging studies? Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2003, 9: 184–195. 10.1002/mrdd.10079

Hariri AR, Weinberger DR: Imaging genomics. Br Med Bull 2003, 65: 259–270. 10.1093/bmb/65.1.259

Gottesman II, Gould TD: The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry 2003, 160: 636–645. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.636

Lesch KP: Linking emotion to the social brain. The role of the serotonin transporter in human social behaviour. EMBO Rep 2007, 8 Spec No: S24-S29.

Fallgatter AJ, Jatzke S, Bartsch AJ, Hamelbeck B, Lesch KP: Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism influences topography of inhibitory motor control. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 1999, 2: 115–120. 10.1017/S1461145799001455

Almasy L, Blangero J: Endophenotypes as quantitative risk factors for psychiatric disease: rationale and study design. Am J Med Genet 2001, 105: 42–44. 10.1002/1096-8628(20010108)105:1<42::AID-AJMG1055>3.0.CO;2-9

Kendler KS, Neale MC: Endophenotype: a conceptual analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2010, 15: 789–797. 10.1038/mp.2010.8

Durston S: Imaging genetics in ADHD. Neuroimage 2010, 53: 832–838. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.071

Durston S, de Zeeuw P, Staal WG: Imaging genetics in ADHD: a focus on cognitive control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009, 33: 674–689. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.009

Castellanos FX, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Milham MP, Tannock R: Characterizing cognition in ADHD: beyond executive dysfunction. Trends Cogn Sci 2006, 10: 117–123. 10.1016/j.tics.2006.01.011

Silva KL, Guimaraes-da-Silva PO, Grevet EH, Victor MM, Salgado CA, Vitola ES, Mota NR, Fischer AG, Contini V, Picon FA, Karam RG, Belmonte-de-Abreu P, Rohde LA, Bau CH: Cognitive deficits in adults with adhd go beyond comorbidity effects. J Atten Disord 2013,17(6):483–8. 10.1177/1087054711434155

Rosvold HE, Mirsky A, Sarason I, Bransome ED, Beck LH: A continuous performance test of brain damage. J Consult Psychol 1956, 20: 343–350.

Baehne CG, Ehlis AC, Plichta MM, Conzelmann A, Pauli P, Jacob C, Gutknecht L, Lesch KP, Fallgatter AJ: Tph2 gene variants modulate response control processes in adult ADHD patients and healthy individuals. Mol Psychiatry 2009, 14: 1032–1039. 10.1038/mp.2008.39

Franke B, Vasquez AA, Johansson S, Hoogman M, Romanos J, Boreatti-Hummer A, Heine M, Jacob CP, Lesch KP, Casas M, Ribases M, Bosch R, Sanchez-Mora C, Gomez-Barros N, Fernandez-Castillo N, Bayes M, Halmoy A, Halleland H, Landaas ET, Fasmer OB, Knappskog PM, Heister AJ, Kiemeney LA, Kooij JJ, Boonstra AM, Kan CC, Asherson P, Faraone SV, Buitelaar JK, Haavik J, et al.: Multicenter analysis of the SLC6A3/DAT1 VNTR haplotype in persistent ADHD suggests differential involvement of the gene in childhood and persistent ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35: 656–664. 10.1038/npp.2009.170

Brown AB, Biederman J, Valera E, Makris N, Doyle A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Mick E, Spencer T, Faraone S, Seidman L: Relationship of DAT1 and adult ADHD to task-positive and task-negative working memory networks. Psychiatry Res 2011, 193: 7–16. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.01.006

Dresler T, Ehlis AC, Heinzel S, Renner TJ, Reif A, Baehne CG, Heine M, Boreatti-Hummer A, Jacob CP, Lesch KP, Fallgatter AJ: Dopamine transporter (SLC6A3) genotype impacts neurophysiological correlates of cognitive response control in an adult sample of patients with ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35: 2193–2202. 10.1038/npp.2010.91

Heinzel S, Dresler T, Baehne CG, Heine M, Boreatti-Hummer A, Jacob CP, Renner TJ, Reif A, Lesch KP, Fallgatter AJ, Ehlis AC: COMT x DRD4 Epistasis Impacts Prefrontal Cortex Function Underlying Response Control. Cereb Cortex 2013, 23: 1453–1462. 10.1093/cercor/bhs132

Arcos-Burgos M, Castellanos FX, Pineda D, Lopera F, Palacio JD, Palacio LG, Rapoport JL, Berg K, Bailey-Wilson JE, Muenke M: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population isolate: linkage to loci at 4q13.2, 5q33.3, 11q22, and 17p11. Am J Hum Genet 2004, 75: 998–1014. 10.1086/426154

Arcos-Burgos M, Jain M, Acosta MT, Shively S, Stanescu H, Wallis D, Domene S, Velez JI, Karkera JD, Balog J, Berg K, Kleta R, Gahl WA, Roessler E, Long R, Lie J, Pineda D, Londono AC, Palacio JD, Arbelaez A, Lopera F, Elia J, Hakonarson H, Johansson S, Knappskog PM, Haavik J, Ribases M, Cormand B, Bayes M, Casas M, et al.: A common variant of the latrophilin 3 gene, LPHN3, confers susceptibility to ADHD and predicts effectiveness of stimulant medication. Mol Psychiatry 2010, 15: 1053–1066. 10.1038/mp.2010.6

Lange M, Norton W, Coolen M, Chaminade M, Merker S, Proft F, Schmitt A, Vernier P, Lesch KP, Bally-Cuif L: The ADHD-susceptibility gene lphn3.1 modulates dopaminergic neuron formation and locomotor activity during zebrafish development. Mol Psychiatry 2012, 17: 946–954. 10.1038/mp.2012.29

Fallgatter AJ, Ehlis AC, Dresler T, Reif A, Jacob CP, Arcos-Burgos M, Muenke M, Lesch KP: Influence of a Latrophilin 3 (LPHN3) risk haplotype on event-related potential measures of cognitive response control in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013, 23: 458–468. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.11.001

Brown AB, Biederman J, Valera EM, Doyle AE, Bush G, Spencer T, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Makris N, LaViolette PS, Oscar-Berman M, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ: Effect of dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3) variation on dorsal anterior cingulate function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2010, 153B: 365–375.

Rapport LJ, Friedman SR, Tzelepis A, Van Voorhis A: Experienced emotion and affect recognition in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology 2002, 16: 102–110.

Hoogman M, Aarts E, Zwiers M, Slaats-Willemse D, Naber M, Onnink M, Cools R, Kan C, Buitelaar J, Franke B: Nitric oxide synthase genotype modulation of impulsivity and ventral striatal activity in adult ADHD patients and healthy comparison subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2011, 168: 1099–1106.

Reif A, Herterich S, Strobel A, Ehlis AC, Saur D, Jacob CP, Wienker T, Topner T, Fritzen S, Walter U, Schmitt A, Fallgatter AJ, Lesch KP: A neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS-I) haplotype associated with schizophrenia modifies prefrontal cortex function. Mol Psychiatry 2006, 11: 286–300. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001779

Hoogman M, Onnink M, Cools R, Aarts E, Kan C, Arias Vasquez A, Buitelaar J, Franke B: The dopamine transporter haplotype and reward-related striatal responses in adult ADHD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013, 23: 469–478. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.05.011

Paloyelis Y, Mehta MA, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Kuntsi J: Striatal sensitivity during reward processing in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012, 51: 722–732. e729 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.006

Cadesky EB, Mota VL, Schachar RJ: Beyond words: how do children with ADHD and/or conduct problems process nonverbal information about affect? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000, 39: 1160–1167. 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00016

Corbett B, Glidden H: Processing affective stimuli in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Neuropsychol 2000, 6: 144–155. 10.1076/chin.6.2.144.7056

Singh SD, Ellis CR, Winton AS, Singh NN, Leung JP, Oswald DP: Recognition of facial expressions of emotion by children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Modif 1998, 22: 128–142. 10.1177/01454455980222002

Sinzig J, Morsch D, Lehmkuhl G: Do hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention have an impact on the ability of facial affect recognition in children with autism and ADHD? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008, 17: 63–72. 10.1007/s00787-007-0637-9

Pelc K, Kornreich C, Foisy ML, Dan B: Recognition of emotional facial expressions in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Neurol 2006, 35: 93–97. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.01.014

Passarotti AM, Sweeney JA, Pavuluri MN: Differential engagement of cognitive and affective neural systems in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2010, 16: 106–117. 10.1017/S1355617709991019

Critchley H, Daly E, Phillips M, Brammer M, Bullmore E, Williams S, Van Amelsvoort T, Robertson D, David A, Murphy D: Explicit and implicit neural mechanisms for processing of social information from facial expressions: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp 2000, 9: 93–105. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200002)9:2<93::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-Z

Wildgruber D, Ackermann H, Kreifelts B, Ethofer T: Cerebral processing of linguistic and emotional prosody: fMRI studies. Prog Brain Res 2006, 156: 249–268.

Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, Lunsford JR, Horsey SE, Reising MM, Thomas LA, Fromm SJ, Towbin K, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2010, 167: 61–69. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043

Plessen KJ, Bansal R, Zhu H, Whiteman R, Amat J, Quackenbush GA, Martin L, Durkin K, Blair C, Royal J, Hugdahl K, Peterson BS: Hippocampus and amygdala morphology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006, 63: 795–807. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.795

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Newcorn J, Fowler JS, Telang F, Solanto MV, Logan J, Wong C, Ma Y, Swanson JM, Schulz K, Pradhan K: Brain dopamine transporter levels in treatment and drug naive adults with ADHD. Neuroimage 2007, 34: 1182–1190. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.014

Pauli P, Conzelmann A, Mucha RF, Weyers P, Baehne CG, Fallgatter AJ, Jacob CP, Lesch KP: Affect-modulated startle reflex and dopamine D4 receptor gene variation. Psychophysiology 2010, 47: 25–33. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00923.x

Garcia-Garcia M, Clemente I, Dominguez-Borras J, Escera C: Dopamine transporter regulates the enhancement of novelty processing by a negative emotional context. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48: 1483–1488. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.01.018

Caspi A, Langley K, Milne B, Moffitt TE, O'Donovan M, Owen MJ, Polo Tomas M, Poulton R, Rutter M, Taylor A, Williams B, Thapar A: A replicated molecular genetic basis for subtyping antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008, 65: 203–210. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.24

Reif A, Nguyen TT, Weissflog L, Jacob CP, Romanos M, Renner TJ, Buttenschon HN, Kittel-Schneider S, Gessner A, Weber H, Neuner M, Gross-Lesch S, Zamzow K, Kreiker S, Walitza S, Meyer J, Freitag CM, Bosch R, Casas M, Gomez N, Ribases M, Bayes M, Buitelaar JK, Kiemeney LA, Kooij JJ, Kan CC, Hoogman M, Johansson S, Jacobsen KK, Knappskog PM, et al.: DIRAS2 is associated with adult ADHD, related traits, and co-morbid disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36: 2318–2327. 10.1038/npp.2011.120

Brown SM, Peet E, Manuck SB, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, Ferrell RE, Hariri AR: A regulatory variant of the human tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene biases amygdala reactivity. Mol Psychiatry 2005, 10: 884–888. 805 10.1038/sj.mp.4001716

Ehlis AC, Bauernschmitt K, Dresler T, Hahn T, Herrmann MJ, Roser C, Romanos M, Warnke A, Gerlach M, Lesch KP, Fallgatter AJ, Renner TJ: Influence of a genetic variant of the neuronal growth associated protein Stathmin 1 on cognitive and affective control processes: an event-related potential study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2011, 156B: 291–302.

Philipsen A: Differential diagnosis and comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) in adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006,256(Suppl 1):i42-i46.

Doyle AE, Willcutt EG, Seidman LJ, Biederman J, Chouinard VA, Silva J, Faraone SV: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder endophenotypes. Biol Psychiatry 2005, 57: 1324–1335. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.015

Levy F, Hay DA, McStephen M, Wood C, Waldman I: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a category or a continuum? Genetic analysis of a large-scale twin study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997, 36: 737–744. 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00009

Muglia P, Jain U, Inkster B, Kennedy JL: A quantitative trait locus analysis of the dopamine transporter gene in adults with ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27: 655–662.

Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR: Intermediate phenotypes and genetic mechanisms of psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006, 7: 818–827. 10.1038/nrn1993

Mattay VS, Goldberg TE, Fera F, Hariri AR, Tessitore A, Egan MF, Kolachana B, Callicott JH, Weinberger DR: Catechol O-methyltransferase val158-met genotype and individual variation in the brain response to amphetamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100: 6186–6191. 10.1073/pnas.0931309100

Ehlis AC, Reif A, Herrmann MJ, Lesch KP, Fallgatter AJ: Impact of catechol-O-methyltransferase on prefrontal brain functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32: 162–170. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301151

Ehlis AC, Pauli P, Herrmann MJ, Plichta MM, Zielasek J, Pfuhlmann B, Stober G, Ringel T, Jabs B, Fallgatter AJ: Hypofrontality in schizophrenic patients and its relevance for the choice of antipsychotic medication: an event-related potential study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2012, 13: 188–199. 10.3109/15622975.2011.566354

Faraone SV, Mick E: Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010, 33: 159–180. 10.1016/j.psc.2009.12.004

Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S: The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011, 68: 444–454. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189

Plomp E, Van Engeland H, Durston S: Understanding genes, environment and their interaction in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: is there a role for neuroimaging? Neuroscience 2009, 164: 230–240. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.024

Ribases M, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Sanchez-Mora C, Bosch R, Richarte V, Palomar G, Gastaminza X, Bielsa A, Arcos-Burgos M, Muenke M, Castellanos FX, Cormand B, Bayes M, Casas M: Contribution of LPHN3 to the genetic susceptibility to ADHD in adulthood: a replication study. Genes Brain Behav 2011, 10: 149–157. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00649.x

Amos W, Driscoll E, Hoffman JI: Candidate genes versus genome-wide associations: which are better for detecting genetic susceptibility to infectious disease? Proc Biol Sci 2011, 278: 1183–1188. 10.1098/rspb.2010.1920

McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, Ioannidis JP, Hirschhorn JN: Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet 2008, 9: 356–369. 10.1038/nrg2344

Blokland GA, McMahon KL, Thompson PM, Martin NG, de Zubicaray GI, Wright MJ: Heritability of working memory brain activation. J Neurosci 2011, 31: 10882–10890. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5334-10.2011

Blokland GA, McMahon KL, Hoffman J, Zhu G, Meredith M, Martin NG, Thompson PM, de Zubicaray GI, Wright MJ: Quantifying the heritability of task-related brain activation and performance during the N-back working memory task: a twin fMRI study. Biol Psychol 2008, 79: 70–79. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.03.006

Durston S, Mulder M, Casey BJ, Ziermans T, van Engeland H: Activation in ventral prefrontal cortex is sensitive to genetic vulnerability for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2006, 60: 1062–1070. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.020

Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID: Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Hum Genet 2009, 126: 51–90. 10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x

Distel MA, Carlier A, Middeldorp CM, Derom CA, Lubke GH, Boomsma DI: Borderline personality traits and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: a genetic analysis of comorbidity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2011, 156B: 817–825.

Todd RD, Jong YJ, Lobos EA, Reich W, Heath AC, Neuman RJ: No association of the dopamine transporter gene 3′ VNTR polymorphism with ADHD subtypes in a population sample of twins. Am J Med Genet 2001, 105: 745–748. 10.1002/ajmg.1611

Todd RD, Neuman RJ, Lobos EA, Jong YJ, Reich W, Heath AC: Lack of association of dopamine D4 receptor gene polymorphisms with ADHD subtypes in a population sample of twins. Am J Med Genet 2001, 105: 432–438. 10.1002/ajmg.1403

Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Larsson JO: Genetic contributions to the development of ADHD subtypes from childhood to adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006, 45: 973–981. 10.1097/01.chi.0000222787.57100.d8

Sonuga-Barke EJ: Psychological heterogeneity in AD/HD–a dual pathway model of behaviour and cognition. Behav Brain Res 2002, 130: 29–36. 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00432-6

Sonuga-Barke E, Bitsakou P, Thompson M: Beyond the dual pathway model: evidence for the dissociation of timing, inhibitory, and delay-related impairments in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010, 49: 345–355.

Kooij SJ, Bejerot S, Blackwell A, Caci H, Casas-Brugue M, Carpentier PJ, Edvinsson D, Fayyad J, Foeken K, Fitzgerald M, Gaillac V, Ginsberg Y, Henry C, Krause J, Lensing MB, Manor I, Niederhofer H, Nunes-Filipe C, Ohlmeier MD, Oswald P, Pallanti S, Pehlivanidis A, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Rastam M, Ryffel-Rawak D, Stes S, Asherson P: European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10: 67. 10.1186/1471-244X-10-67

Oner O, Akin A, Herken H, Erdal ME, Ciftci K, Ay ME, Bicer D, Oncu B, Bozkurt OH, Munir K, Yazgan Y: Association among SNAP-25 gene DdeI and MnlI polymorphisms and hemodynamic changes during methylphenidate use: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. J Atten Disord 2011, 15: 628–637. 10.1177/1087054710374597

Acknowledgments

Thomas Dresler was partly supported by the LEAD graduate school [GSC1028], a project of the Excellence Initiative of the German federal and state governments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TD and BB reviewed the literature, wrote the first draft and later finalized the manuscript after the other authors have reviewed it. TE rewrote parts of the manuscript and drafted the affective-motivational paradigms part. KPL rewrote the manuscript especially regarding details of genetics. ACE and AJF designed the concept of the review article and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ann-Christine Ehlis and Andreas J Fallgatter contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dresler, T., Barth, B., Ethofer, T. et al. Imaging genetics in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a way towards pathophysiological understanding?. bord personal disord emot dysregul 1, 6 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-6673-1-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-6673-1-6