Abstract

Introduction

Based on previous studies, a preclinical classification for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been proposed. However, 1) specificity of the different neuronal injury (NI) biomarkers has not been studied, 2) subjects with subtle cognitive impairment but normal NI biomarkers (SCINIB) have not been included in the analyses and 3) progression to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia of the AD type (DAT), referred to here as MCI/DAT, varies between studies. Therefore, we analyzed data from 486 cognitively normal (CN) and 327 DAT subjects in the AD Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)-1/GO/2 cohorts.

Results

In the ADNI-1 cohort (median follow-up of 6 years), 6.3% and 17.0% of the CN subjects developed MCI/DAT after 3 and 5 years follow-up, respectively. NI biomarker cutoffs [structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau] were established in DAT patients and memory composite scores were calculated in CN subjects in a cross-sectional sample (n = 160). In the complete longitudinally followed CN ADNI cohort (n = 326, median follow-up of 2 years), CSF and MRI values predicted an increased conversion to MCI/DAT. Different NI biomarkers showed important disagreements for classifying subjects as abnormal NI [kappa = (−0.05)-(0.33)] and into AD preclinical groups. SCINIB subjects (5.0%) were more prevalent than AD preclinical stage 3 subjects (3.4%) and showed a trend for increased progression to MCI/DAT.

Conclusions

Different NI biomarkers lead to different classifications of ADNI subjects, while structural MRI and CSF tau measures showed the strongest predictive value for progression to MCI/DAT. The newly defined SCINIB category of ADNI subjects is more prevalent than AD preclinical stage individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease (ND), characterized and diagnosed by the presence of tau neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques in the central nervous system [1]. Other neurodegenerative and non-degenerative disease pathologies commonly coexist in patients with dementia of the AD type (DAT) and community-dwelling subjects [2–5]. The advent of molecular and neuroimaging AD biomarkers has enabled researchers to better predict the pathologies underlying DAT [6, 7] and to formulate research diagnostic criteria [8]. These advances have led to the proposal of a hypothetical AD model [9] for the pathological and biomarker changes to emerge over one or more decades before the onset of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [10–12]. It is thought that amyloid deposition precedes cognitive changes by one or more decades and cognitive changes appear when measured amyloid levels approach a plateau. Using this model, a preclinical staging for AD has been proposed based on successive and additive presence of Aβ amyloid deposition (Stage 1), evidence of neuronal injury (NI) biomarkers (Stage 2) and subtle cognitive impairment (Stage 3) all of which precedes MCI and DAT. A separate category for cognitively impaired ADNI subjects with positive NI biomarkers in the absence of Aβ amyloid deposition (suspected non-Alzheimer pathophysiology (sNAP) has also been proposed [13]. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with Aβ amyloid ligands and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ measurements methods used for estimation of Aβ amyloid deposition are highly correlated [14, 15], but for the detection of NI due to AD pathology several other markers are suggested. These include CSF tau, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET). In addition, classification strategies using neuroimaging biomarkers are based on assessments of specific or composite regions of interest (ROI) or pattern analysis methods.

Two studies analyzing different cohorts have described the baseline and longitudinal outcomes of preclinical AD staging with a median follow-up of one and 3.9 years [16, 17]. These studies obtained different risk assessments of conversion from CN to MCI or DAT (referred to here as MCI/DAT) and used different sets of NI biomarkers. Although indications are given for the different NI biomarkers [18], no assessment or comparison of the different biomarker modalities and processing has been performed in a single study and this variability might affect the classification of the subjects into the different diagnostic categories. There is another potential and unexplored category of subjects composed of individuals with subtle cognitive impairment with normal neuronal injury biomarkers (SCINIB) independent of the presence or absence of amyloid deposition.

In this study, we 1) compared the agreement of different NI biomarkers and found important differences in prevalence for the different stages of AD, 2) assessed the risk of conversion to DAT in non-demented ADNI subjects that was associated with the different biomarkers to select the best combination of NI biomarkers for the classification of CN subjects, and 3) evaluated the progression of CN subjects to MCI/DAT based on these selected biomarkers.

Materials and methods

Participants and neuropsychological testing

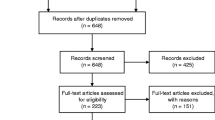

Data used in the preparation of this article, was downloaded from the ADNI database November 1st 2013 [19] (http://adni.loni.ucla.edu/ and Additional file 1: supplementary material). Diagnosis of MCI and DAT was established as previously described [20–22] (Additional file 1: Supplementary Material). We included 486ADNI-1/GO/2 CN subjects who were divided into two groups (Figure 1):

-

a)

The first group (Figure 1, blue square) was included in the longitudinal analysis (n = 326), based on a follow-up of at least 1 year and presence of baseline CSF Aβ1–42 or FDG PET measurements (Table 1).

-

b)

The second group of CN subjects (Figure 1, green square, Additional file 1:Table S2) was composed of CN subjects without follow-up (n = 100) or without CSF or FDG PET measures (n = 60). These subjects were used to estimate the cutoffs that define subtle cognitive changes for the CN.

-

327

ADNI-1/GO/2 DAT subjects were included to estimate the NI cutoffs for the preclinical AD classification (Additional file 1: Table S2). A summary composite memory measure developed by Crane et al. [23] was used to estimate the presence of subtle cognitive changes.

CSF biomarker collection and analysis

Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181 were measured using the multiplex xMAP Luminex platform (Luminex Corp, Austin, TX) with Innogenetics (INNO-BIA AlzBio3; Ghent, Belgium; for research use–only reagents) immunoassay kit–based reagents (see Additional file 1: supplementary material) [7, 24].

MRI and FDG-PET acquisition and processing

1.5-T MRI and 3-T non-accelerated sagittal volumetric 3D MPRAGE MRI images were acquired at each performance site for the ADNI 1 and ADNI-GO/2, respectively (http://adni.loni.ucla.edu). Only MRIs which passed the quality control evaluations were included. To estimate hippocampal volumes (HV) measures, cortical grey matter (GM) volumes were processed using Free-surfer software package version 4.4 and 5.1 image processing framework for the 1.5 and 3-T MRI images, respectively (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) [25, 26]. We estimated in an independent dataset a method to obtain the adjusted HV (aHV; adjusted for intracranial volume (ICV)) for the MRIs (Additional file 1: supplementary material) (Figure 2a). The SPARE-AD (Spatial Pattern of Abnormality for Recognition of Early Alzheimer’s disease) is an index that captures brain atrophy related to AD [27, 28]. FDG-PET data were acquired and reconstructed with the use of measured-attenuation correction and the specified reconstruction algorithm for each scanner type according to a standardized protocol (http://adni.loni.ucla.edu/). Images were downloaded and pre-processing using SPM5 by investigators at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). We calculated a pattern based summary score, the hypometabolic convergence index (HCI) [29] and an anatomically defined ROI, the posterior cingulate (PC-FDG-PET with FDG-images using pons as reference region) CMRgl (cerebral metabolic rate for glucose).

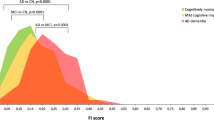

Validation of aHV transformation, cognitive and biomarker cutoffs and progression of ADNI-1 CN subjects. Comparisons of cross-validated 1.5-T and corresponding 3-T (a). Progression from CN to MCI/DAT in the ADNI-1 cohort (b). Prevalence of the different CN categories with the use of different neuronal injury biomarkers (c). Conversion of CN subjects to MCI/DAT in adjusted in ADNI-1/GO/2 CN subjects using aHV (d) (dotted line represents cutpoint of the heaviside function), SPARE-AD (e), t-tau/Aβ1–42 ratio (f) and the CN categories defined by the combined NI biomarkers (g).

Definition of preclinical AD stages and biomarker and cognitive cutoffs

Presence of Aβ amyloid deposition consistent with AD pathology and T-tau and p-tau181 cutoffs were selected based on cutoffs previously validated in a cohort including autopsy confirmed AD subjects [7]. For the MRI and FDG-PET NI biomarkers we did not have any available cutoffs based on a neuropathologically validated sample. We therefore calculated the cutoffs for the remaining NI biomarkers based on values that would give 90% sensitivity for DAT (Additional file 1: Table S3, Additional file 1: Figure S1) [13]. Using this methodology, we could not define a cutoff which was useful for the SPARE-AD score due to its high specificity (only 4.9% of the CN subjects had an abnormal SPARE-AD score). Cutoffs for the memory score indicative of subtle cognitive changes were estimated based on the 10th percentile in the CN subjects not included in the longitudinal analysis [13]. Subjects were categorized as NI presence if any of the two selected biomarkers was abnormal. Subjects were classified into the following categories (Additional file 1: Table S4): 1) Stage 0 [13] (normal Aβ1–42, normal NI biomarker and normal cognition), 2) Stage 1 (abnormal Aβ1–42, normal NI biomarkers and normal cognition), 3) Stage 2 (abnormal Aβ1–42, abnormal NI biomarker and normal cognition), 4) Stage 3 [18] (abnormal Aβ1–42, abnormal NI biomarker and abnormal cognition), 5) sNAP [13] (normal Aβ1–42 and abnormal NI biomarker) and 6) SCINIB (subtle cognitive impairment with normal NI biomarkers independent of Aβ1–42) using the different NI biomarkers.

Statistical analysis

For the comparison of baseline clinical, biomarker and demographic variables Mann–Whitney U and Kruskall-Wallis tests were applied for the comparison of 2 or 3 groups respectively. For analyses involving an association with longitudinal outcomes, a Box-Cox transformation was applied to non-normally distributed variables. Cutoffs for classification models were selected as described in previous sections. Agreement between the groups defined by the different NI biomarkers was defined using the Cohen’s kappa index. The Cox proportional hazard (PH) model was used to study the progression of CN subjects to MCI/DAT. This model included age, gender education and the presence of APOE ϵ4 allele in addition to the studied biomarker. Quantitative predictors were normalized and standardized in order to be able to compare the effect size of the different NI biomarkers in the PH model. Standardized biomarker values were set so that positive values would indicate abnormal values. The PH assumption was tested analyzing the correlation between the Schoenfeld residuals and survival time. In cases where that the assumption was not meet, a PH with a heaviside function was applied. No correction for multiple comparisons was applied, because all of our NI biomarkers were specified a priori based on the recommended NI biomarkers recommended in the preclinical AD criteria [18] and the exploratory nature of our analysis. Statistical significance was set at the p < 0.05 level. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Description of the cohort

In the total ADNI-1/GO/2 cohort, 43 (8.8%) of the CN subjects converted to MCI, 10 (2.1%) converted to DAT (8 had an MCI diagnosis before the DAT) and 11 (2.3%) died (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Of the MCI subjects, 35 (81%) were thought to have a DAT cognitive impairment profile, whereas 8 (19%) were thought to have developed MCI due to other etiologies (Additional file 1: Table S5). All demented patients had a probable DAT diagnosis. In Figure 2b we plot the survival plot for the ADNI-1 CN cohort with a median follow-up of 313 weeks (1st quartile 159 weeks; 3rd quartile: 364 weeks) for comparison with other studies. 86.5% of the ADNI-1 CN subjects had a follow-up of at least 3 years with a progression to MCI/DAT of 6.3%, whereas 56.1% had a follow-up of at least 5 years with a progression to MCI/DAT of 17.0%.

Comparison of groups based on NI biomarkers and cognitive cutoffs

The different NI biomarkers showed a low agreement, with Cohen’s kappa index values ranging from −0.05 to 0.33 (values below the diagonal in Table 2) and overall agreement between the different NI biomarkers ranged from 45.3% (SPARE-AD and PC-FDG-PET) to 79.0% (SPARE-AD and T-tau). Therefore, the potential use of any single biomarker or combinations of NI biomarkers can lead to important distinctions among the different categories of non-demented ADNI subjects as summarized in Figure 2c.

Clinical progression based on the different NI biomarkers and cognitive measures

Due to the absence of any specific recommendations regarding the use of different combinations of NI biomarkers to classify the CN subjects, we tested the associated risk of progression of CN subjects to MCI/DAT based on the different NI biomarkers in the Cox PH models (Table 3). Only the MRI and the t-tau/Aβ1–42 values were associated with a higher risk of progression to MCI/DAT (Figure 2d-f) while lower baseline memory measures were the strongest predictors. Finally, we also selected for further analysis a biomarker from each modality showing the strongest association with progression, i.e.t-tau for the CSF and aHV for the neuroimaging, and called this model the combined NI model.

Clinical progression based on the preclinical AD stages using different combinations of NI biomarkers and clinical measures

Of the 326 ADNI-1/GO/2 subjects with longitudinal follow-up, 238 had measurements for the selected NI biomarkers. Five out of the twelve SCINIB subjects had abnormal Aβ1–42. The association of the different categories with progression to MCI/DAT is summarized in and Table 4 (Figure 2g). Stage 3 was associated with progression to MCI/DAT and the SCINIB category showed a trend. Additional file 1: Table S6 lists the results obtained using neuroimaging-only or CSF-only NI biomarkers. When subjects were categorized using only CSF NI biomarker the Stage 3, we found that subjects in the sNAP or SCINIB category were associated with progression to MCI/DAT. In none of the models did stage 1 and 2 show an association with faster progression.

Discussion

Our study describes for the first time the unexplored variability of NI biomarkers among CN subjects, and we found that CSF tau and structural MRI measures, either aHV or SPARE-AD, were the strongest predictors of conversion to MCI/DAT from among a very comprehensive set of NI biomarkers. Selecting the best biomarkers, we classified the CN subjects and included the SCINIB category in our analyses since they had not been analysed in previous study, and we showed a higher prevalence of the SCINIB category than the AD preclinical stage 3. While only the AD preclinical stage was associated with increased progression to MCI/DAT, the SCINIB category showed a trend for progression which could become significant with longer follow up of these subjects.

Two previous studies have described the distribution of the AD preclinical stages and the progression of CN to MCI/DAT [16, 17] and a third study has described the neuropsychological changes, but not the diagnostic changes associated with the preclinical stages of AD [30]. In the Washington University (WU) study, with a median follow-up of 3.9 years, the 5-year progression from CN to a clinical dementia rating of at least 0.5 deemed to be due to AD was 10% [17]. On the other hand, the Mayo Clinic (MC) population-based study showed the same progression rate, namely 10%, but with a follow-up of a single year. In our study, the conversion from CN to MCI/DAT was 6.3% at 3 years of follow-up and 17.0% at 5 years of follow-up in the ADNI-1 cohort (median follow-up of five years). Neither the ADNI nor the WU cohorts are population-based studies like the MC cohort and comparisons should be performed to assess baseline differences that explain these findings. In addition a third study described longitudinal memory and executive decline in AD preclinical stages 1 and 2 but not in the sNAP category, although conversion to MCI/DAT was not studied [30].

In our study we included a wide range of standardized AD biomarker measurements that are used as measures of NI in the preclinical AD criteria [18]. In addition, for the MRI and FDG-PET we included two types of measures, i.e. regions of interest and machine learning methods. Similarly, two NI measures were available for the CSF, namely t-tau and p-tau181. The performed analyses showed that all the NI measures, even those within the same modality showed an important disagreement for the classification of subjects according to the consistent absence or presence of NI biomarkers (Table 2 and Figure 2c). This is not surprising due to the fact that NI biomarkers track changes in different stages of the disease and at a different rate [9]. For example, in this study aHV was only associated with faster progression in the first years. The measures that showed the highest agreement were CSF t-tau and p-tau181, which showed a high correlation as well as PC-FDG-PET and aHV, as described previously [31, 32]. In addition, biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity, like the SPARE-AD, cannot be used to categorize subjects using the previous approaches [13] due to the small overlap between CN and DAT subjects and therefore cutoffs based on the longitudinal outcomes might be needed for biomarkers with a high accuracy. Many NI biomarkers might not be disease specific. This is, for example, the case of MRI HV and medial temporal lobe measures that can be affected by different ND and show additive effect from ND [5, 33, 34]. This also can be the case of FDG-PET measures. Nevertheless, p-tau181, which would be expected to be the most specific NI biomarker, was the one that was associated with the highest prevalence of sNAP cases. Interestingly, a recent study reported that in some cases incident amyloid positivity is preceded by NI positivity [35]. These results underscore the importance of standardized studies which include different NI measures in order to assess the implications of using different biomarkers and how this can affect comparability of different studies.

The WU study used the presence of either abnormal t-tau or p-tau181 as NI biomarkers and the MC study used the presence of either abnormal FDG–PET or HCV. None of the studies assessed the impact of using a wider panel of different NI measures. From a diagnostic point of view, specific criteria are needed to define the different preclinical AD stages and studies should assess the different sources of variability for the different NI biomarkers as well as the specificity that each one offers.

Whereas from a research perspective it might be important to examine and compare in the same study different types of biomarkers this is not case in clinical scenarios that require cost effective and reproducible measures linked to clinical outcomes. Here, we studied several biomarkers in the ADNI cohort and found that structural MRI and CSF t-tau were the best predictors for conversion to MCI/DAT, and therefor they were used for the combined model. This is in agreement with previous studies that have shown that either brain atrophy [36, 37] or CSF biomarkers [30, 38, 39] are associated with an increased risk of progression of CN subjects to MCI/DAT. Finally, a recent study in a small subset of ADNI patients has shown that a combination of biomarkers can predict the conversion from CN subjects to MCI/DAT [40] and therefore biomarkers combinations might be able to predict the appearance of cognitive symptoms in subjects at risk with higher accuracy than the preclinical stages and reflecting the different underlying pathologies in subjects with cognitive impairment [5].

SCINIB is a new category outside the AD hypothetical model that includes subjects with subtle cognitive changes who were not previously identified by the array of NI biomarkers used in AD studies. This category was more prevalent in the ADNI cohort than the stage 3 group using the combined NI model. The SCINIB group was composed of a mixture of subjects with normal and abnormal CSF Aβ1–42 values and this group showed a trend for increased conversion to MCI/DAT. Previous studies have not included this group in their main analyses, because investigators have focused on validating the preclinical AD stages or subjects with NI measures. However, this might lead to the impression that the preclinical staging explains most of the conversion of CN subjects to MCI/DAT. It is not surprising that the SCINIB group might be associated with clinical progression because it is defined by neuropsychological measures that are also in part used to establish the clinical diagnosis (but this would also apply to the preclinical AD stage 3 groups). This finding underscores the importance of not excluding SCINIB subjects from studies and characterizing them longitudinally in order to understand their longitudinal prognosis and potential biomarkers that identify these subjects.

Conclusion

We confirm that there is increased progression for the AD preclinical stage 3 and probably SCINIB, but there is a high classification variability regarding the AD preclinical, sNAP and SCINIB categories based on the selection of the NI biomarkers that may reflect different aspects of disease. Therefore specific and standardized criteria are needed to be able to apply a reproducible and robust classification strategy and new approaches for the definition of cutoffs will be needed for biomarker with a high accuracy. In addition, a large percentage of subjects with baseline subtle memory changes fell into the SCINIB category, which needs further study to characterize its longitudinal outcome and the underlying pathological changes.

References

Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Hyman BT: National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta neuropathologica 2012, 123: 1–11. 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3

Toledo JB, Brettschneider J, Grossman M, Arnold SE, Hu WT, Xie SX, Lee VM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ: CSF biomarkers cutoffs: the importance of coincident neuropathological diseases. Acta Neuropathol 2012, 124: 23–35. 10.1007/s00401-012-0983-7

Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, Brettschneider J, Xie SX, Grossman M, Monsell SE, Kukull WA, Trojanowski JQ: Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Centre. Brain: J neurol 2013, 136: 2697–2706. 10.1093/brain/awt188

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA: Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology 2007, 69: 2197–2204. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24

Toledo J, Cairns N, Da X, Chen K, Carter D, Fleisher A, Householder E, Ayutyanont N, Roontiva A, Bauer R, Eisen P, Shaw LM, Davatzikos C, Weiner MW, Reiman EM, Morris JC, Trojanowski JQ: Clinical and multimodal biomarker correlates of ADNI neuropathological findings. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2013, 1: 65. 10.1186/2051-5960-1-65

McMillan CT, Irwin DJ, Avants BB, Powers J, Cook PA, Toledo JB, McCarty Wood E, Van Deerlin VM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Grossman M: White matter imaging helps dissociate tau from TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013, 84: 949–955. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304418

Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Annals of neurology 2009, 65: 403–413. 10.1002/ana.21610

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH: The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2011, 7: 263–269. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, Trojanowski JQ: Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet neurology 2013, 12: 207–216. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0

Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, Szoeke C, Macaulay SL, Martins R, Maruff P, Ames D, Rowe CC, Masters CL: Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet neurology 2013, 12: 357–367. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9

Toledo JB, Xie SX, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM: Longitudinal change in CSF Tau and Abeta biomarkers for up to 48 months in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 126: 659–670. 10.1007/s00401-013-1151-4

Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Lesnick TG, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Pankratz VS, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Mielke MM, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Petersen RC: Brain beta-amyloid load approaches a plateau. Neurology 2013, 80: 890–896. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182840bbe

Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Lowe V, Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Ivnik RJ, Roberts RO, Rocca WA, Boeve BF, Petersen RC: An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology 2012, 71: 765–775. 10.1002/ana.22628

Toledo JB, Vanderstichele H, Figurski M, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Jack CR Jr, Jagust W, Decarli C, Toga AW, Toledo E, Xie SX, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM: Factors affecting Abeta plasma levels and their utility as biomarkers in ADNI. Acta neuropathologica 2011, 122: 401–413. 10.1007/s00401-011-0861-8

Landau SM, Lu M, Joshi AD, Pontecorvo M, Mintun MA, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jagust WJ: Comparing positron emission tomography imaging and cerebrospinal fluid measurements of beta-amyloid. Annals of neurology 2013, 74: 826–836. 10.1002/ana.23908

Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Lowe V, Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Ivnik RJ, Roberts RO, Boeve BF, Petersen RC: Short-term clinical outcomes for stages of NIA-AA preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2012, 78: 1576–1582. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563bbe

Vos SJ, Xiong C, Visser PJ, Jasielec MS, Hassenstab J, Grant EA, Cairns NJ, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM: Preclinical Alzheimer's disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12: 957–965. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH: Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2011, 7: 280–292. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003

Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Cairns NJ, Green RC, Harvey D, Jack CR, Jagust W, Liu E, Morris JC, Petersen RC, Saykin AJ, Schmidt ME, Shaw L, Shen L, Siuciak JA, Soares H, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ: The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 2013, 9: e111-e194. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.1769

Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E: Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999, 56: 303–308. 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303

Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR Jr, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW: Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology 2010, 74: 201–209. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984, 34: 939–944. 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939

Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, Insel P, Mackin RS, Gross A, Jones RN, Mukherjee S, Curtis SM, Harvey D, Weiner M, Mungas D: Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Brain imaging and behavior 2012, 6: 502–516. 10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z

Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Figurski M, Coart E, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon AJ, Lewczuk P, Dean RA, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta neuropathologica 2011, 121: 597–609. 10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0

Reuter M, Rosas HD, Fischl B: Highly accurate inverse consistent registration: a robust approach. NeuroImage 2010, 53: 1181–1196. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.020

Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B: Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. NeuroImage 2012, 61: 1402–1418. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.084

Fan Y, Shen D, Gur RC, Gur RE, Davatzikos C: COMPARE: classification of morphological patterns using adaptive regional elements. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007, 26: 93–105.

Toledo JB, Da X, Bhatt P, Wolk DA, Arnold SE, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Davatzikos C: Relationship between plasma analytes and SPARE-AD defined brain atrophy patterns in ADNI. PloS one 2013, 8: e55531. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055531

Chen K, Ayutyanont N, Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Reschke C, Lee W, Liu X, Bandy D, Alexander GE, Thompson PM, Shaw L, Trojanowski JQ, Jack CR Jr, Landau SM, Foster NL, Harvey DJ, Weiner MW, Koeppe RA, Jagust WJ, Reiman EM: Characterizing Alzheimer's disease using a hypometabolic convergence index. NeuroImage 2011, 56: 52–60. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.049

van Harten AC, Smits LL, Teunissen CE, Visser PJ, Koene T, Blankenstein MA, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM: Preclinical AD predicts decline in memory and executive functions in subjective complaints. Neurology 2013, 81: 1409–1416. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a8418b

Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V: Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101: 4637–4642. 10.1073/pnas.0308627101

Fouquet M, Desgranges B, Landeau B, Duchesnay E, Mezenge F, de la Sayette V, Viader F, Baron JC, Eustache F, Chetelat G: Longitudinal brain metabolic changes from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. Brain : J Nneurol 2009, 132: 2067–2058.

Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, Schneider JA: TDP-43 Pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA neurology 2013, 70: 1418. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3961

Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, Baker M, Fardo DW, Kryscio RJ, Scheff SW, Jicha GA, Jellinger KA, Van Eldik LJ, Schmitt FA: Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta neuropathologica 2013, 126: 161–177. 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1

Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Lowe V, Vemuri P, Mielke MM, Jones DT, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Gregg BE, Pankratz VS, Petersen RC: Amyloid-first and neurodegeneration-first profiles characterize incident amyloid PET positivity. Neurology 2013, 81: 1732–1740. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435556.21319.e4

Rusinek H, De Santi S, Frid D, Tsui WH, Tarshish CY, Convit A, de Leon MJ: Regional brain atrophy rate predicts future cognitive decline: 6-year longitudinal MR imaging study of normal aging. Radiology 2003, 229: 691–696. 10.1148/radiol.2293021299

Driscoll I, Davatzikos C, An Y, Wu X, Shen D, Kraut M, Resnick SM: Longitudinal pattern of regional brain volume change differentiates normal aging from MCI. Neurology 2009, 72: 1913–1906.

Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM: Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid (42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Archives of neurology 2007, 64: 343–349. 10.1001/archneur.64.3.noc60123

Li G, Sokal I, Quinn JF, Leverenz JB, Brodey M, Schellenberg GD, Kaye JA, Raskind MA, Zhang J, Peskind ER, Montine TJ: CSF tau/Abeta42 ratio for increased risk of mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Neurology 2007, 69: 631–639. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267428.62582.aa

Rizk-Jackson A, Insel P, Petersen R, Aisen P, Jack C, Weiner M: Early Indications of Future Cognitive Decline: Stable versus Declining Controls. PloS one 2013, 8: e74062. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074062

Acknowledgements

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; GE Healthcare; Innogenetics, N.V.; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to Rev October 14, 2013 support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (http://www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. JQT is the William Maul Measey-Truman G. Schnabel, Jr., Professor of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr. Weiner reports stock/stock options from Elan, Synarc, travel expenses from Novartis, Tohoku University, Fundacio Ace, Travel eDreams, MCI Group, NSAS, Danone Trading, ANT Congress, NeuroVigil, CHRU-Hopital Roger Salengro, Siemens, AstraZeneca, Geneva University Hospitals, Lilly, University of California, San Diego–ADNI, Paris University, Institut Catala de Neurociencies Aplicades, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Ipsen, Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease, Pfizer, AD PD meeting, Paul Sabatier University, board membership for Lilly, Araclon, Institut Catala de Neurociencies Aplicades, Gulf War Veterans Illnesses Advisory Committee, VACO, Biogen Idec, Pfizer, consultancy from AstraZeneca, Araclon, Medivation/Pfizer, Ipsen, TauRx Therapeutics, Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, ExonHit Therapeutics, Servier, Synarc, Pfizer, Janssen, honoraria from NeuroVigil, Insitut Catala de Neurociencies Aplicades, PMDA/Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Tohoku University, commercial research support from Merck, Avid; government research support, DOD, VA, outside the submitted work. Dr. Shaw serves as consultant for Janssen AI R & D Janssen AI R & D and Lilly, outside the submitted work. Dr. Jagust has served as consultant for Genentech, Synarc, Siemens, F. Hoffman La Roche, Tau Rx, and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, outside the submitted work. Dr. Arnold reports grants from NIH, the American Health Assistance Foundation and the Marian S Ware Alzheimer’s Program, several pharmaceutical companies, other from Universities, pharmaceutical companies and advisory/speaking honoraria from Universities, pharmaceutical companies and law firms. Dr. Jack, Reiman, Chen, Wolk, Davatzikos, Da and Toledo have nothing to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript, contributed to interpretation of the data and critical review of the manuscript and study concept. XD and CD processed and analyzed the MRI data. KC and EMR processed and analyzed the FDG-PET data. JBT drafted the manuscript and performed the statistical analyses. JQT drafted the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

40478_2014_198_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1: ADNI 1 criteria for recruitment of CN and DAT subjects. Table S2. ADNI-1 and ADNI-GO/2 DAT patients included to derive cutoff values and CN subjects without longitudinal follow-up or lack of CSF or FDG-PET measurements. Table S3. Biomarker and clinical cutoffs with 90% DAT sensitivity and corresponding specificities obtained in CN not included in longitudinal analysis and cutoffs based on 10th percentile in CN not included in longitudinal analysis. Table S4. Criteria for classifying ADNI subjects into the different CN, prodromal DAT and clinically manifest DAT categories described in this study. Table S5. Clinical diagnoses of MCI subjects whose impairment was not attributed to AD. Table S6. Association between preclinical AD stages and conversion to MCI/DAT. Cox hazards models were adjusted for age, gender and APOE ϵ4 presence. Figure S1. Neuronal injury and memory cutoffs. aHV (a), SPARE-AD (b), HCI (c), FDG-PET ROI score (d) and memory composite score (e) values in CN and DAT subjects in the samples of subjects used for the estimation of cutoffs. Dashed line represents the selected cutoff. (DOCX 197 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Toledo, J.B., Weiner, M.W., Wolk, D.A. et al. Neuronal injury biomarkers and prognosis in ADNI subjects with normal cognition. acta neuropathol commun 2, 26 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-5960-2-26

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-5960-2-26