Abstract

Background

Several general diseases cause blindness in patients with simultaneous combined retinal artery and vein occlusion.

Methods/patients

We examined 14 patients with acute unilateral visual loss due to combined retinal artery and venous occlusions. All 14 patients presented at the Polyclinic over a period of about 3 years. Fluorescein angiography was carried out in 12 patients to confirm the diagnosis. Ten patients underwent Doppler sonography and 11 echocardiography.

Results

Concerning systemic diseases, 11 of our 14 patients presented several cardiovascular risk factors, i.e., immunocytoma and arterial hypertension and hypercholesterolemia in one patient; another patient had chronic bronchitis, tachycardia and hypercholesterolemia. Six patients presented coagulation anomalies, and eight patients had arterial hypertension.

Doppler sonography revealed normal carotid arteries in nine of ten patients. In 8 of 11 patients, echocardiography displayed no cardiac abnormalities.

Ophthalmoscopy revealed no emboli in any of these patients.

Conclusion

Unilateral simultaneous combined incomplete retinal artery and venous occlusions should be considered as one entity. Eleven of our patients presented comorbidities reflecting several cardiovascular risk factors. Immunological diseases, malignancies and coagulopathies can cause this ocular disorder, resulting in blindness. No emboli were found in any of these patients. Patients suffering from acute visual loss must be examined for the presence of systemic diseases to enable therapy at an early stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systemic diseases in noninflammatory isolated branch or central retinal artery occlusions or isolated branch or central retinal vein occlusions have been described in large patient cohorts by several authors [1–3]. Regarding the rare entity of combined retinal artery and venous occlusions, cardiovascular risk factors have generally been documented in case reports involving few patients in most publications [4–50].

Three different types of combined retinal artery and vein occlusions (often incomplete) have been reported:

-

1.

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO).

-

2.

CRVO with branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO).

-

3.

CRVO with cilioretinal artery occlusion (CLRAO).

Criteria for the entity of combined retinal artery and venous occlusion are acute unilateral visual loss with retinal edema (retinal whitening of the posterior pole or along an artery), with or without a cherry red spot on the macula, retinal hemorrhages, enlarged, tortuous veins, delayed arterial dye filling of arteries and prolonged arteriovenous transit time in fluorescein angiography. Complete occlusions of the central retinal vein and central retinal artery are extremely rare. Several publications have reported central retinal vein occlusion in association with cilioretinal artery occlusion [7, 22, 23, 29–32, 41, 42, 48]. Hayreh et al. [22] argued that sudden CRVO associated with cilioretinal artery occlusion results in a marked rise in intraluminal pressure in the capillary bed. Cilioretinal artery occlusion is a hemodynamic block, not caused by emboli.

McLeod [31] pointed out that the probability of cilioretinal infarction increases with the increasing severity of CRVO. Pathogenesis of the combined CRVO with CLRAO is regarded as a particular entity that differs from the pathogenesis of combined central retinal artery obstruction and central retinal vein occlusion.

The choroidal arterial steal mechanism can influence the development of combined CRV and CRA occlusions.

Unilateral combined occlusion of the central retinal artery (CRAO) and central retinal vein (CRVO) was first described by Gross in 1907 [18] in a 48-year-old woman with anemia. Different causes of combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion have been reported. We propose various explanations for the disease’s development in our 14 patients.

Case presentation

Methods and patients

The 14 patients (5 female and 9 male) had a mean age of 57.6 years (33–75). All were examined at the Polyclinic of the University Eye Hospital over a period of approximately 3 years. The right eye was affected in nine, the left eye in five patients. The patients were referred because of acute unilateral visual loss.

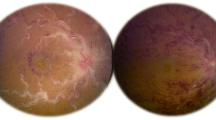

Unilateral combined retinal artery and vein occlusions were observed in all our patients. Ten (Table 1) presented combined CRVO and CRAO, and three patients had combined CRVO and BRAO (Table 2). One patient showed a combined cilioretinal artery occlusion (CLRAO) and CRVO Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Etiologies

Diagnoses of ocular and systemic diseases (including patients with cilioretinal artery occlusion and CRVO)

Ocular diseases

Posterior scleritis: (Shukla et al. [43]), blunt ocular trauma (Noble & Alvarez [34]), vitrectomy (Verma et al., [50]).

Retrobulbar anesthesia (Brown et al. [8], Giuffré et al. [16], Sullivan et al. [46]), thrombosis of the orbital superior ophthalmic vein (Hsu et al. [21]), meningeal carcinomatosis with compression of the retrobulbar optic nerve (Schaible & Golnik [40]).

Inflammatory ocular and/or orbital diseases of unknown origin (Bender [6]), papillophlebitis (Cassen et al. [9]) orbital inflammatory pseudotumor (Foroozan: [15]).

General diseases, immunological diseases.

Antiphospholipid syndrome (Ang et al. [4], Durukan [14]).

Systemic lupus erythematosus (Brown et al. [8], Cobo-Soriano et al. [11], Coppeto & Lessell [12]).

Churg-Strauss syndrome (Hamann [20]), Behçet’s disease (Richards [37]), interferon treatment (Jenisch et al. [24]).

Vascular diseases.

Arterial hypertension (Brazitikos et al. [7], Brown et al. [8], Limaye et al. [29], Vallé et al. [49], McLeod & Ring [30]), diabetes mellitus (Arikan et al. [5], Brown et al. [8]).

Migraine (Cassen et al. [9], Glacet-Bernard et al. [17]), Raynaud’s syndrome (Glacet-Bernard et al. [17]), smoker (Vallé et al. [49]).

Oral contraceptives (Brazitikos et al. [7], Glacet-Bernard et al. [17]), syphilis (Smith [44]).

Coagulopathy.

Activated protein C resistance (Vallé et al. [49]).

Inflammatory disease.

Sinus thrombosis.

Sinusitis and thrombosis in the sinus cavernosus (Richards: [37]).

Malignancies.

Prostate cancer (Jorizzo: [25]).

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Guyer et al. [19], Saatci [39]).

Lymphocytic leukemia (Chan et al. [10], Richards [37]).

In the ten patients with visual loss (Table 1), the right eye was affected in six and the left eye in four. For the examinations, fluorescein angiography was carried out in eight patients, revealing delayed arterial filling in six (patients 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10) and no filling delay in two (patients 7, 8). Optic disk swelling was observed in five patients (nos. 2, 3, 4, 8, 10); cotton-wool spots (CWSs) were detected in two patients (nos. 2 and 6).

Five patients (nos. 2, 3, 5, 7, 8) experienced distinct visual improvement after treatment, one patient (no. 6) a slight improvement, three patients (nos. 1, 9, 10) no visual change and one patient (no. 4) a slight deterioration.

In the three patients with visual loss (Table 2), the right eye was affected (nos. 11, 12, 13). All three underwent fluorescein-angiography, which revealed delayed arterial filling in one patient. We observed distinct visual improvement after treatment in one patient (no. 12) and no change in visual acuity in two patients (nos. 11 and 13).

In one patient with CLRAO and CRVO (no. 14), the left eye was affected. Fluorescein angiography revealed delayed dye filling of the cilioretinal artery. His visual acuity improved after treatment.

Doppler sonography was carried out in ten patients; nine had normal carotid arteries. Only one patient demonstrated bilateral, moderately sized carotid stenoses.

Echocardiography was carried out in 11 patients, yielding normal findings in 8 (nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 13, 14). One patient (no. 7) was suspected of having a diastolic disturbance during myocardial relaxation, while another patient (no. 11) presented ventricular hypertrophy. Another patient (no. 12) revealed a patent foramen ovale. The 48-year-old male with the patent foramen ovale had arterial hypertension and was a chronic smoker (as co-morbidity).

Treatment in some patients consisted of isovolemic hemodilution, aspirin administration or other anticoagulants. One patient received corticosteroids (no. 1). In those with systemic diseases, treatment was carried out in cooperation with internists. In one patient (no. 1, Table 1) with combined CRVO and CRAO, vitrectomy and endolaser treatment of the retina were carried out. One patient (no. 14, Table 3) revealed a combined CRVO with a cilioretinal arterial occlusion (CLRAO). This 39-year-old male was diagnosed with increased diastolic blood pressure. His visual acuity was 20/400 initially, improving slightly to 20/200 after anticoagulant treatment and lowering his blood pressure.

After treatment, we noted a distinct improvement in visual acuity (more than two lines) in six patients (nos. 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 12), slight improvement in one patient (no. 6), no change in visual acuity in five patients (nos. 1, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14) and deterioration in one patient after a recurrence (no. 4).

The patients whose visual acuity improved substantially were those with BRAO and incomplete CRVO, autoimmune disease (no. 5), hyperhomocysteinemia (no. 7), hypertension (nos. 3, 12) and bronchopneumonia (nos. 2, 8).

Results

Eight patients were diagnosed with arterial hypertension, three with hypercholesterolemia and six with coagulation anomalies. Three patients were chronic smokers. Eleven of our 14 patients presented comorbidities in the form of several cardiovascular risk factors.

Comorbidities were striking in our patients, as at least 11 of them presented several diseases, i.e., immunocytoma and arterial hypertension in conjunction with hypercholesterolemia (patient 1); chronic bronchitis with tachycardia and hypercholesterolemia (patient 2); arterial hypertension and hypercholesterolemia (patient 3); autoimmune disease with evidence of serum antimitochondrial antibodies and a tendency to arterial hypotension (patient 5); prostate cancer, anemia, a coagulation anomaly and diabetes mellitus (patient 6); hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperuricemia and a suspected diastolic disturbance of cardiac relaxation (patient 7); bronchopneumonia and a bilateral, medium-sized carotid stenosis (patient 8); heterozygous factor V mutation associated with venous thrombosis of the leg and arterial hypertension (patients 9 and 10); chronic smoking habit and a patent foramen ovale (patient 12); chronic smoker and a coagulation disorder (patient 13).

The three remaining (nos. 4, 11 and 14) presented less serious comorbidities: patient 4 had slightly elevated blood pressure and slightly increased homocysteine, patient 11 suffered from extremely high blood pressure, and patient 14 (who had an occlusion of a large cilioretinal artery) suffered from arterial hypertension. We identified no additional risk factors in these three patients.

Six patients presented coagulation anomalies in conjunction with other cardiovascular diseases, for instance the patient with paraneoplastic syndrome and diabetes mellitus. Arterial hypertension was diagnosed in 8 of 14 patients. One patient (no. 12) revealed a patent foramen ovale and hypertension. We detected no emboli in any of the patients ophthalmoscopically.

Discussion

Concerning the risk profile, the cardiovascular risk factors for retinal artery occlusion are arterial hypertension, carotid artery diseases, cardiac rhythm disorders and cardiac valvular diseases, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia and chronic smoking [3]. The cause of retinal artery occlusions in most patients is embolic. In our patients with combined CRAO with CRVO, however, no emboli were detected.

The main ophthalmoscopic feature of this entity is the absence of an embolus. Carotid artery examination and echocardiography in most of our patients failed to reveal cardiovascular anomalies that could lead to emboli. We carried out Doppler sonography in nine patients, of whom eight had normal carotid arteries. Only one patient revealed a moderate bilateral carotid stenosis.

Brown et al. [8] also reported the absence of carotid stenosis in most of their patients. Echocardiography was carried out in 11 patients in our group. Eight of them revealed no abnormalities, and only one patient, a chronic smoker, presented a patent foramen ovale (no. 12). Another patient revealed ventricular hypertrophy (no. 11), and a diastolic relaxation disturbance was suspected in an additional patient (no. 7).

The risk factors for retinal vein occlusion are systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus and open-angle glaucoma [1]. In patients with combined CRAO with CRVO, however, the risk profile seems to differ because a combination of cardiovascular risk factors is essential in this entity. Eleven of our 14 patients presented comorbidities in the form of several cardiovascular risk factors.

The literature describes several systemic diseases, some of which were detected in our patients, that can cause this vascular entity, i.e., coagulation disturbances, arterial hypertension, arteriosclerosis, mechanical vessel compression at the optic nerve level, vascular inflammation, immunological diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and interferon therapy.

Comorbidities are also described in some patients in the literature. Vallée et al. [49] reported on 1 of 11 patients who suffered from hypertension, anticardiolipin syndrome and von Willebrand syndrome. Another patient revealed hypercholesterolemia and protein S deficiency. In an additional patient who smoked, hypertension and monoclonal gammopathy were diagnosed.

Glacet-Bernard et al. [17] described one of seven patients who was a chronic smoker and presented hypertension as well as hypercholesterolemia, hyperuricemia and hyperfibrinogenemia.

A 62-year-old patient suffered from prostate cancer and diabetes mellitus [25]. Leibovitch et al. [27] diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus with lupus nephritis and severe hypertension in a 23-year-old man.

We assume that combined CRAO and CRVO occur simultaneously or within a short interval. However, an exception to this was published by Ang et al. [4]: a patient with an antiphospholipid syndrome initially revealed a CRVO and 1 month later an ophthalmic artery occlusion. Rachitskaya et al. [36] reported a CRVO in a 50-year-old man who presented a CRAO 2 weeks later.

Total bilateral blindness in conjunction with a complete arterial and venous interruption in blood flow was described by Coppeto & Lessell [12]. They reported severe bilateral retinal vasculitis with total retinal circulation arrest from thrombosis in most of the retinal vessels, including major arterioles, due to lupus erythematosus. That patient’s history also differed from our patients’ medical histories. Bilateral visual deterioration or blindness has also been reported [5, 6, 19].

We diagnosed a combined occlusion of a cilioretinal artery (CLRAO) with a CRVO in one patient (no. 14). Schatz et al. [41] observed ten patients presenting this combined occlusion. Schatz et al. noted pulsations in the cilioretinal artery in five eyes. They emphasized that the cilioretinal artery occlusion was not embolic. Due to lower perfusion pressure, the cilioretinal artery becomes relatively occluded. Their ten patients, all under 50 years of age, revealed cilioretinal artery occlusion associated with a non-ischemic CRVO. This disease’s prognosis is generally good. Eight of those nine eyes demonstrated a final visual acuity of 20/30 or better.

The prognosis of combined CRAO and CRVO, even if incomplete, is very poor, including blindness if left untreated. Such combined vascular retinal occlusions are caused by systemic diseases that should be treated at an early stage by an ophthalmologist and internist working together. As the systemic diseases in our patients are fundamental, treatment should be carried out in cooperation with internists.

Vallée et al. [49] are the only authors who treated patients with combined CRAO and CRVO via fibrinolysis. They selectively perfused urokinase via the femoral artery into the ophthalmic artery. Seven of eleven of their patients’ vision improved substantially, while one revealed an intravitreal hemorrhage with visual deterioration.

Patients with a combined retinal arteriovenous occlusion should be carefully followed up over months or years because of threatening neovascularization glaucoma. Rubeosis iridis was observed by Brown et al. [8], Smith [44], Stowe et al. [45], Richards [37], Sullivan et al. [46], Duker et al. [13] and Rachitskaya et al. [36].

Brown et al. [8] observed rubeosis iridis in 17 out of 21 patients (81%) with at least 6-month follow-up.

Conclusions

The essential findings in our 14 patients were:

-

1)

Unilateral simultaneous combined incomplete retinal artery and vein occlusions should be considered as one entity,

-

2)

Eleven patients (78.6%) revealed co-morbidities presenting as cardiovascular risk factors such as arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and chronic smoking. Immunological diseases, malignancies and coagulopathies may lead to this ocular disorder, causing blindness.

-

3)

Normal echocardiography in eight patients and normal Doppler sonography findings in nine patients were revealed.

-

4)

The mean age was 57.6 years (33–75).

-

5)

None of our patients presented an embolism. This is therefore the main difference from an isolated CRAO or BRAO, as they often are caused by embolic events.

-

6)

Patients suffering from acute visual loss must be examined for the presence of a systemic disease to enable treatment at an early stage.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report and any accompanying images.

References

Eye disease case–control study group: Risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 1996, 114: 545–554.

O’Mahoney PRA, Wong DT, Ray JG: Retinal vein occlusion and traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis. Arch Ophthalmol 2008, 126: 692–699.

Schmidt D, Hetzel A, Geibel-Zehender A, Schulte-Mönting J: Systemic diseases in non-inflammatory branch and central retinal artery occlusion - an overview of 416 patients. Eur J Med Res 2007, 12: 595–603.

Ang LPK, Lim ATH, Yap EY: Central retinal vein and ophthalmic artery occlusion in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Eye 2004, 18: 439–440.

Arikan G, Osman Saatci A, Soylev MF, Kocak N: Bilateral combined cilioretinal artery and central retinal vein occlusion. Ann Ophthalmol 2006, 38: 135–137.

Bender MB: Simulatneous closure of all the central retinal vessels. Am J Ophthalmol 1935, 18: 148–150.

Brazitikos PD, Pournaras CJ, Othenin-Girard P, Borruat FX: Pathogenetic mechanisms in combined cilioretinal artery and retinal vein occlusion: a reappraisal. Int Ophthalmol 1993, 17: 235–242.

Brown GC, Duker JS, Lehman R, Eagle RC: Combined central retinal artery-central vein obstruction. Int Ophthalmol 1993, 17: 9–17.

Cassen JH, Tomsak RL, DeLuise VP: Mixed arteriovenous occlusive disease of the fundus. J Clin Neuro-ophthalmol 1985, 5: 164–168.

Chan WM, Liu DTL, Lam DSC: Combined central retinal artery and vein occlusions as the presenting signs of ocular relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2004, 128: 134.

Cobo-Soriano R, Sanchez-Ramon A, Aparicio MJ, et al.: Antiphospholipid antibodies and retinal thrombosis in patients without risk factors: a prospective case–control study. Am J Ophthalmol 1999, 128: 725–732.

Coppeto J, Lessell S: Retinopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Ophthalmol 1977, 95: 794–797.

Duker JS, Cohen MS, Brown GC, Sergott RC, McNamara JA: Combined branch retinal artery and central retinal vein obstruction. Retina 1990, 10: 105–112.

Durukan AH, Akar Y, Bayraktar MZ, Dinc A, Sahin OF: Combined retinal artery and vein occlusion in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Can J Ophthalmol 2005, 40: 87–89.

Foroozan R: Combined central retinal and vein occlusion from orbital inflammatory pseudotumour. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004, 32: 435–449.

Giuffre G, Vadala M, Manfre L: Retrobulbar anesthesia complicated by combined central retinal vein and artery occlusion and massive vitreoretinal fibrosis. Retina 1995, 15: 439–441.

Glacet-Bernard A, Gaudric A, Touboul C, Coscas G: Occlusion de la veine centrale de la rétine avec occlusion d’une artère cilio-rétinienne: a propos de 7 cas. J Fr Ophtalmol 1987, 10: 269–277.

Gross O: Über einen Fall von Verschluss beider Centralgefäße. Arch Augenheilkd 1907, 56: 257–258.

Guyer DR, Green WR, Schachat AP, Bastacky S, Miller NR: Bilateral ischemic optic neuropathy and retinal vascular occlusions associated with lymphoma and sepsis. Clinicopathologic correlation. Ophthalmology 1990, 97: 882–888.

Hamann S, Johansen S: Combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion in Churg-Strauss syndrome: case report. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2006, 84: 703–706.

Hsu J, Ibarra MS, Jacobs D, Galetta SL, Brucker AJ: Combined central retinal vein and artery occlusion associated with an isolated superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis. Retina 2004, 24: 452–454.

Hayreh SS, Fraterrigo L, Jonas J: Central retinal vein occlusion associated with cilioretinal artery occlusion. Retina 2008, 28: 581–594.

Iijima H, Gohdo T, Tsukahara S: Familial dysplasminogenemia with central retinal vein and cilioretinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1998, 126: 312–314.

Jenisch T, Dietrich-Ntoukas T, Renner AB, Helbig H, Gamulescu MA: Kombinierter retinaler arteriovenöser Verschluss unter Interferon-beta-Therapie. Ophthalmologe 2012, 109: 71–75.

Jorizzo PA, Klein ML, Shults WT, Linn ML: Visual recovery in combined central retinal artery and central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1987, 104: 358–363.

Kremer I, Gilad E, Cohen S, Ben Sira I: Combined arterial and venous retinal occlusion as a presenting sign of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ophthalmologica 1985, 191: 114–118.

Leibovitch I, Goldstein M, Loewenstein A, Barak A: Combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2001, 40: 1195–1196.

Levy J, Baumgarten A, Rosenthal G, Rabinowitz R, Lifshitz T: Consecutive central retinal artery and vein occlusions in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Retina 2002, 22: 784–786.

Limaye SR, Tang RA, Pilkerton AR: Cilioretinal circulation and branch arterial occlusion associated with preretinal arterial loops. Am J Ophthalmol 1980, 89: 834–839.

McLeod D, Ring CP: Cilio-retinal infarction after retinal vein occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 1976, 60: 419–427.

McLeod D: Central retinal vein occlusion with cilioretinal infarction from branch flow exclusion and choroidal arterial steal. Retina 2009, 29: 1381–1395.

Murray DC, Christopoulou D, Hero M: Combined central retinal vein occlusion and cilioretinal artery occlusion in a patient on hormone replacement therapy. Br J Ophthalmol 2000, 84: 549–550.

Nicolo M, Artioli S, La-Mattina GC, Ghiglione D, Calabria G: Branch retinal artery occlusion combined with branch retinal vein occlusion in a patient with hepatitis C treated with interferon and ribavirin. Eur J Ophthalmol 2005, 15: 811–814.

Noble MJ, Alvarez EV: Combined occlusion of the central retinal artery and central retinal vein following blunt ocular trauma: a case report. Br J Ophthalmol 1987, 71: 834–836.

Özdek S, Yülek F, Güreik G, Aydin B, Hasanreisoglu B: Simultaneous central retinal vein and retinal artery branch occlusions in two patients with homocystinaemia. Eye 2004, 18: 942–945.

Rachitskaya A, Lee RK, Dubovy SR, Schiff ER: Combined central retinal vein and central retinal artery occlusions and neovascular glaucoma with interferon treatment. Europ J Ophthalmol 2012, 22: 284–287.

Richards RD: Simultaneous occlusion of the central retinal artery and vein. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1979, 77: 191–209.

Rubio JE, Charles S: Interferon-associated combined branch retinal artery and central retinal vein obstruction. Retina 2003, 23: 546–548.

Saatci AO, Düzovali Ö, Özbek Z, Saatci I, Sarialioglu F: Combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion in a child with systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol 1999, 22: 125–127.

Schaible ER, Golnik KC: Combined obstruction of the central retinal artery and vein associated with meningeal carcinomatosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1993, 111: 1467–1468.

Schatz H, Fong ACO, McDonald HR, Johnson RN, Joffe L, Wilkinson CP, de-Laey JJ, Yanuzzi LA, Wendel RT, Joondeph BC, Angioletti LV, Meredith TA: Cilioretinal artery occlusion in young adults with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 1991, 98: 594–601.

Seo MS, Woo JM, Seo JJ: Neovascular glaucoma associated with cilioretinal artery occlusion combined with perfused central retinal vein occlusion. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2002, 46: 198–202.

Shukla D, Mohan KC, Rao N, Kim R, Namperumalsamy P, Cunningham ET: Posterior scleritis causing combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion. Retina 2004, 24: 467–469.

Smith JL: Acute blindness in early syphilis. Arch Ophthalmol 1973, 90: 256–258.

Stowe GC, Zakov ZN, Albert DM: Central retinal vascular occlusion associated with oral contraceptives. Am J Ophthalmol 1978, 86: 798–801.

Sullivan KL, Brown GC, Forman AR, Sergott RC, Flanagan JC: Retrobulbar anesthesia and retinal vascular obstruction. Ophthalmology 1983, 90: 373–377.

Tavola A, Vigano’D’Angelo S, Bandello F, Brancato R, Parlavecchia M, Safa O, D’Angelo A: Central retinal vein and branch artery occlusion associated with inherited plasminogen deficiency and high lipoprotein(a) levels: a case report. Thrombosis Res 1995, 80: 327–331.

Theoulakis PE, Livieratour A, Petropoulos IK, Lepidas J, Brinkmann CK, Katsimpris JM: Cilioretinal artery occlusion combined with central retinal vein occlusion – a report of two cases and review of the literature. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2010, 227: 302–305.

Vallée JN, Paques M, Aymard A, Santiago PY, Adeleine P, Gaudric A, Merland JJ: Combined central retinal arterial and venous obstruction: emergency ophthalmic arterial fibrinolysis. Radiology 2002, 223: 351–359.

Verma L, Venkatesh P, Tewari HK: Combined retinal artery and central retinal vein occlusion following pars plana vitrectomy. Ophthalm Surg Lasers 1999, 30: 317–319.

Acknowledgement

I thank Dr. Nicolas Feltgen (University Eye Hospital Göttingen) for his support in preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declared that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, D. Comorbidities in combined retinal artery and vein occlusions. Eur J Med Res 18, 27 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783X-18-27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783X-18-27