Abstract

Cutaneous melanoma carries the potential for substantial morbidity and mortality in the solid organ transplant population. We systematically reviewed the literature published from January 1995 to January 2012 to determine the overall relative risk and prognosis of melanoma in transplant recipients. Our search identified 7,512 citations. Twelve unique non-overlapping studies reported the population-based incidence of melanoma in an inception cohort of solid organ transplant recipients. Compared to the general population, there is a 2.4-fold (95% confidence interval, 2.0 to 2.9) increased incidence of melanoma after transplantation. No population-based outcome data were identified for melanoma arising post-transplant. Data from non-population based cohort studies suggest a worse prognosis for late-stage melanoma developing after transplantation compared with the general population. For patients with a history of pre-transplant melanoma, one population-based study reported a local recurrence rate of 11% (2/19) after transplantation, although staging and survival information was lacking. There is a need for population-based data on the prognosis of melanoma arising pre- and post-transplantation. Increased incidence and potentially worse melanoma outcomes in this high-risk population have implications for clinical care in terms of prevention, screening and reduction of immunosuppression after melanoma development post-transplant, as well as transplantation decisions in patients with a history of pre-transplant melanoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Important advances in solid organ transplantation have led to improved patient survival over recent decades. With prolonged survival, the long-term complications of immunosuppressive therapy have become increasingly important. Decreased immune surveillance after transplant leads to a three- to fourfold increased risk of malignancy compared to the general population[1, 2].

Skin cancer is the most common form of post-transplant malignancy, particularly squamous cell carcinoma (relative risk 14 to 82)[3–6]. Although the incidence of melanoma is increased to a lesser degree than for squamous cell carcinoma, the potential for melanoma metastasis can introduce significant morbidity and mortality. Previous studies of melanoma in the transplant population have often had low numbers of cases, which precludes precise estimation of relative risk and produces variable estimates across studies. In addition, data on clinical outcomes such as metastasis or mortality are scarce for melanoma arising pre- and post-transplantation.

With its increased incidence and significant metastatic potential, melanoma has important implications for the care of transplant recipients. We aim to systematically review the published literature to determine the overall relative risk and prognosis of melanoma in solid organ transplant recipients.

Materials and methods

On 12 January 2012, electronic literature searches were conducted in Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to week 1 of January 2012, and In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations from 1946 to the present) and EMBASE (1980 to week 2 of 2012) to identify eligible studies using a comprehensive search strategy developed in consultation with an information specialist. The search terms consisted of the following: cancer/neoplas*/tumor/tumour/malignan*/carcin*, or melanoma (expanded), and transplant (organ/kidney/renal/heart/cardiac/liver/hepat/lung/pulmonary/pancreas/intestine/spleen) and cohort/incidence/prevalence/prognosis.

Studies were limited to those published after 1995 in English and French. We included studies that estimated the relative risk or reported clinical outcomes (stage, recurrence, metastasis or death) of melanoma in a population-based inception cohort of solid organ transplant recipients (kidney, liver, heart, lung, pancreas or intestine). Studies were not excluded based on a quality assessment.

We initially screened all titles and abstracts to exclude articles that were clearly ineligible. We then reviewed full-text articles for all remaining citations. Reference lists from relevant articles were also reviewed for relevant articles. When needed, we obtained additional data from the study authors by email correspondence. If there were studies with more than a 50% overlap in their patient populations (based on country, year of transplant, type of graft and data source), we included data from only the most recent or inclusive study.

We pre-specified three main systematic review outcomes: the incidence and relative risk of melanoma diagnosed after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population; the outcomes of melanoma diagnosed after solid organ transplantation (post-transplant melanoma), including recurrence, metastasis and mortality (overall and melanoma-specific); and the outcomes of melanoma diagnosed prior to transplantation (pre-transplant melanoma).

For articles reporting incidence data, the pooled standardized incidence ratio (SIR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using weights from a random effects model. The variation in effect sizes attributable to heterogeneity was quantified using the I-squared statistic. To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, we used meta-regression to adjust for the graft organ type (renal/liver versus heart/lung) and the most recent year of transplantation included in the study cohort (>2000 versus ≤2000). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.1.

Results

The literature search identified 4,093 citations from Ovid MEDLINE and 6,311 from EMBASE. After removing duplicates, 7,512 unique citations were identified. We eliminated 7,369 citations based on title or abstract. A full-text review of the remaining 143 articles led to the further exclusion of 125 articles, most commonly because the studies were not population-based (Figure 1).

We identified 17 studies that reported the incidence of melanoma in a population-based cohort of solid organ transplant recipients[3–19]. No eligible studies of post-transplant melanoma outcomes were found. One population-based study reported the outcomes of pre-transplant melanoma. We requested and obtained additional information from the primary author for two studies through email correspondence[12, 20]. (Y Jiang, MD, 7 March 2011, and J Brewer, MD, 24 February 2012).

Incidence of post-transplant melanoma

Among the 17 population-based studies reporting melanoma incidence after transplant, five were excluded to avoid double counting of data that overlapped significantly with other studies[11, 14, 15, 17, 18]. Two Swedish studies collected data from the Swedish National In-patient Registry for patients transplanted between 1970 and 1994[14] and between 1970 and 1997[6]; we excluded the older cohort. A Norwegian study that reported skin cancer incidence in heart and renal transplant recipients[15] was excluded due to significant overlap with a larger study[10] that reported cancer risk after renal transplantation in all Nordic countries. We excluded two Australian[17, 18] studies that overlapped with a more recent study of a larger cohort of renal transplant recipients in Australia and New Zealand[7]. Finally, two studies from the United States used overlapping datasets; we included the more recent and inclusive study[11, 19].

Characteristics of the 12 included studies are listed in Table 1. The study populations were for kidney (N = 5), liver (N = 2), heart (N = 1) and various solid organ transplants (N = 4) performed in North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. There was less than 50% overlap of populations in three included studies from Sweden[6], Denmark[5] and the Nordic countries[10].

Regional cancer registries were the main data source for identifying melanoma diagnoses. All studies reported rates of melanoma in transplant recipients compared to their respective age-, sex- and time-matched general population rates. One study also accounted for race[19].

Overall, transplant recipients have a pooled estimate of 2.4 times (95% confidence interval, 2.0 to 2.9) the risk of melanoma compared to the general population (Figure 2). The overall I-squared was 46% (P = 0.04), indicating moderate heterogeneity between studies. Adjusting for the type of organ graft and the most recent year of transplant in the cohort reduced the I-squared value to 0%. Studies of renal or liver transplant recipients had an absolute increase in SIR of 0.29 compared to studies that included heart or lung transplant recipients (P = 0.01). Studies that included patients transplanted after the year 2000 had an increase in SIR of 0.41 compared to older studies (P = 0.03).

Prognosis of post-transplant melanoma

Our search identified no population-based studies reporting data on outcomes of de novo melanoma arising post-transplantation. We identified ten retrospective, non-population-based cohort studies that compiled data from various sources[20–29]. As many of these papers present overlapping data, the most summative articles are described in Table 2.

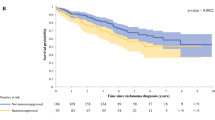

In the largest study reporting on post-transplant melanoma outcomes, Brewer et al. retrospectively identified 638 cases of post-transplant melanoma in the United States collected from three Mayo Clinic databases (Florida, Rochester and Arizona), the Organ Procurement Transplant Network (OPTN) and the Israel Penn International Tumor Transplant Registry (IPITTR). They found that overall survival rates were worse in the transplant population compared to the general population based on Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data. In particular, patients with melanomas with a Breslow depth of 1.51 to 3.00 mm and Clark levels III/IV had significantly worse outcomes compared with the expected survival rates in the general population[20]. A number of earlier publications also reported from these same databases[25, 27–29].

In the second largest non-overlapping study, Matin et al. reported worse outcomes for late stage (T3/T4) melanoma in transplant recipients compared to the general population[26]. This group analyzed cases from the Skin Care in Organ Transplant Patients, Europe network (SCOPE) database, which collects data from 14 transplant dermatology clinics. They compared 81 cases of melanoma in transplant patients to controls matched by age, sex, tumor thickness and ulceration, and found worse outcomes in transplant patients with stage T3/T4 tumors (>2 mm thick). They found outcomes similar to the controls for early stage (T1/T2) melanomas. The hazard ratio for T3/T4 stage tumors was 11.49 (3.6 to 36.8).

Frankenthaler et al. reported on outcomes of 19 melanoma patients who were taking immunosuppressive therapies for renal transplantation (4 patients) or autoimmune conditions (15 patients). Each case was matched to three non-immunosuppressed controls with a similar age, sex, stage and location of primary tumor. They found no significant difference in relapse rates but worse overall survival in the immunosuppressed group, suggesting a more aggressive clinical course[21]. Other smaller, uncontrolled cohort studies have shown variable findings (Table 2).

Post-transplantation prognosis of pre-transplant melanoma

Our search identified one population-based, retrospective, uncontrolled cohort study reporting on post-transplant outcomes of melanoma diagnosed prior to solid organ transplantation (Table 3)[30]. Chapman et al. reported data on cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers) diagnosed before renal transplantation that subsequently recurred post-transplant. From the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA), 19 of 11,894 patients who received renal transplants from 1963 to 1999 had a history of pre-transplant melanoma. Two of the nineteen patients (11%) had melanoma recurrence after transplant. No data on staging or post-transplant metastasis were available.

We also identified two non-population based, retrospective, uncontrolled cohort studies (Table 3)[20, 26]. Brewer et al. examined the post-transplant outcomes of 59 cases of pre-transplant melanoma collected from the IPITTR, OPTN and Mayo Clinic databases[20]. Breslow depth was available for a subset of 17 cases. They reported no recurrences and two melanoma metastases with a mean follow up of 10.5 years. This study encompassed data from two previous reports[25, 28], including data from IPITTR that originally suggested that 6 of 31 patients with pre-transplant melanoma died from post-transplant recurrences[28]. However, these findings could not be replicated by Brewer et al., whose study excluded melanoma diagnoses from IPITTR that were not histopathologically confirmed (personal communication, J Brewer, MD, 24 February 2012).

Matin et al. reported data voluntarily provided by physicians in the SCOPE network database (Table 3). Breslow depth was available for six of nine patients with pre-transplant melanoma. No post-transplant deaths were noted after 3.3 to 42 years of post-melanoma follow-up (median 14 years) and 0.5 to 10.2 years of post-transplant follow-up (median 5 years)[26].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of melanoma incidence and outcomes in the solid organ transplant population. Compared to the general population, there is a 2.4-fold increased incidence of melanoma in the transplant population. No population-based outcome data were identified for melanoma arising post-transplant. Data from non-population-based cohort studies suggest a worse prognosis for late-stage melanoma developing in a transplant population versus a general population. For melanoma arising prior to transplantation, one uncontrolled population-based study found an 11% local recurrence rate post-transplant, although staging and survival data were lacking.

Immune function plays a prominent role in the biological response to melanoma[31]. The increased incidence of melanoma in the transplant population is likely due to decreased immune surveillance, although the oncogenic potential of systemic immunosuppressant medications may also play a role. Reduced immune surveillance may also lead to poorer outcomes in melanoma arising pre- and post-transplant, but clinical data are limited. Late transmission of donor melanoma after up to 32 years of melanoma-free survival in the host suggests that immunosuppression can promote activation of previously dormant melanoma cells[32]. Melanoma regression with removal of immunosuppression has also been described[33], and many of the systemic treatments for metastatic melanoma are immune-activating therapies[34].

In transplant candidates with a history of melanoma, the risk of post-transplant recurrence and metastasis has important implications for the decision to pursue transplantation. The quality of data available to guide this decision is currently limited to uncontrolled, non-population-based reports that lack staging information. Otley et al. proposed a consensus-based framework of waiting time prior to consideration of transplantation, based on melanoma stage[35]. The risks and benefits of pursuing transplantation versus continued dialysis or organ failure in patients with a history of melanoma need to be weighed on a case-by-case basis.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, our review is limited by the quality of the included studies. Only one incidence study adjusted the melanoma rates for race, an important risk factor for skin cancer[19]. This could affect the estimates of relative risk if the racial composition differed between transplant and general populations. Data on the level of immunosuppression were also not available for the identified studies, with inevitable heterogeneity of medications and dosing within each transplant population and between studies. Furthermore, staging information was uniformly lacking, which precluded evaluation of the severity of melanoma at the time of diagnosis in the transplant population versus the general population, and the impact of stage on melanoma outcomes. Finally, the overall heterogeneity of the included incidence studies was moderate, as reflected by the I-squared value of 46%. We explored two potential sources of heterogeneity and found that the graft type and cohort year accounted for all of the between-study variability.

Conclusion

Our systematic review found that there is a 2.4-fold increased incidence of melanoma in the transplant population compared to the general population. Non-population-based data suggest a worse prognosis for late-stage melanoma developing in the transplant population versus the general population. These findings have several implications for clinical practice and research. The significantly increased overall risk of melanoma arising post-transplant means that these patients warrant a multi-pronged approach to primary and secondary prevention, including regular full skin examinations for cancer screening, a low biopsy threshold for suspicious pigmented lesions, and continual education on the importance of sun avoidance and protection. Our study has also identified an important knowledge gap that should be addressed in future research. Population-based studies that account for melanoma stage and risk factors are needed for patients and clinicians to understand better the prognosis of pre- and post-transplant melanoma. These data would help to inform treatment decisions, as tumors known to have a poorer prognosis may require more aggressive management, including significant reduction or discontinuation of immunosuppression. Robust outcome and staging data would also help to inform the decision to pursue, avoid or delay transplantation in patients with a history of melanoma.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- ANZDATA:

-

Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry

- BIDMC:

-

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- IPITTR:

-

Israel Penn International Tumor Transplant Registry

- OPTN:

-

Organ Procurement Transplant Network

- SCOPE:

-

Skin Care in Organ Transplant Patients, Europe network

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

- SIR:

-

standardized incidence ratio.

References

Sheil AG: Development of malignancy following renal transplantation in Australia and New Zealand. Transplant Proc. 1992, 24 (4): 1275-1279.

Gutierrez-Dalmau A, Campistol JM: Immunosuppressive therapy and malignancy in organ transplant recipients: a systematic review. Drugs. 2007, 67 (8): 1167-1198. 10.2165/00003495-200767080-00006.

Moloney FJ, Comber H, O’Lorcain P, O’Kelly P, Conlon PJ, Murphy GM: A population-based study of skin cancer incidence and prevalence in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2006, 154 (3): 498-504. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07021.x.

Collett D, Mumford L, Banner NR, Neuberger J, Watson C: Comparison of the incidence of malignancy in recipients of different types of organ: a UK Registry audit. Am J Transplant. 2010, 10 (8): 1889-1896. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03181.x.

Jensen AO, Svaerke C, Farkas D, Pedersen L, Kragballe K, Sorensen HT: Skin cancer risk among solid organ recipients: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010, 90 (5): 474-479. 10.2340/00015555-0919.

Adami J, Gabel H, Lindelof B, Ekstrom K, Rydh B, Glimelius B, Ekbom A, Adami HO, Granath F: Cancer risk following organ transplantation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 2003, 89 (7): 1221-1227. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601219.

Webster AC, Craig JC, Simpson JM, Jones MP, Chapman JR: Identifying high risk groups and quantifying absolute risk of cancer after kidney transplantation: a cohort study of 15,183 recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007, 7 (9): 2140-2151. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01908.x.

Jiang Y, Villeneuve PJ, Wielgosz A, Schaubel DE, Fenton SS, Mao Y: The incidence of cancer in a population-based cohort of Canadian heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010, 10 (3): 637-645. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02973.x.

Bastiaannet E, der Homan-van Heide JJ, Ploeg RJ, Hoekstra HJ: No increase of melanoma after kidney transplantation in the northern part of The Netherlands. Melanoma Res. 2007, 17 (6): 349-353. 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f0c880.

Birkeland SA, Storm HH, Lamm LU, Barlow L, Blohme I, Forsberg B, Eklund B, Fjeldborg O, Friedberg M, Frodin L, Glattre E, Halvorsen S, Holm NV, Jakobsen A, Jorgensen HE, Ladefoged J, Lindholm T, Lundgren G, Pukkala E: Cancer risk after renal transplantation in the Nordic countries, 1964–1986. Int J Cancer. 1995, 60 (2): 183-189. 10.1002/ijc.2910600209.

Hollenbeak CS, Todd MM, Billingsley EM, Harper G, Dyer AM, Lengerich EJ: Increased incidence of melanoma in renal transplantation recipients. Cancer. 2005, 104 (9): 1962-1967. 10.1002/cncr.21404.

Jiang Y, Villeneuve PJ, Fenton SS, Schaubel DE, Lilly L, Mao Y: Liver transplantation and subsequent risk of cancer: findings from a Canadian cohort study. Liver Transpl. 2008, 14 (11): 1588-1597. 10.1002/lt.21554.

Aberg F, Pukkala E, Hockerstedt K, Sankila R, Isoniemi H: Risk of malignant neoplasms after liver transplantation: a population-based study. Liver Transpl. 2008, 14 (10): 1428-1436. 10.1002/lt.21475.

Lindelof B, Sigurgeirsson B, Gabel H, Stern RS: Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2000, 143 (3): 513-519. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03703.x.

Jensen P, Hansen S, Moller B, Leivestad T, Pfeffer P, Geiran O, Fauchald P, Simonsen S: Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999, 40 (2 Pt 1): 177-186.

Villeneuve PJ, Schaubel DE, Fenton SS, Shepherd FA, Jiang Y, Mao Y: Cancer incidence among Canadian kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007, 7 (4): 941-948. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01736.x.

Vajdic CM, McDonald SP, McCredie MR, van Leeuwen MT, Stewart JH, Law M, Chapman JR, Webster AC, Kaldor JM, Grulich AE: Cancer incidence before and after kidney transplantation. JAMA. 2006, 296 (23): 2823-2831. 10.1001/jama.296.23.2823.

Bouwes Bavinck JN, Hardie DR, Green A, Cutmore S, MacNaught A, O’Sullivan B, Siskind V, Van Der Woude FJ, Hardie IR: The risk of skin cancer in renal transplant recipients in Queensland, Australia. A follow-up study. Transplantation. 1996, 61 (5): 715-721. 10.1097/00007890-199603150-00008.

Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF, Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Wolfe RA, Goodrich NP, Bayakly AR, Clarke CA, Copeland G, Finch JL, Fleissner ML, Goodman MT, Kahn A, Koch L, Lynch CF, Madeleine MM, Pawlish K, Rao C, Williams MA, Castenson D, Curry M, Parsons R, Fant G, Lin M: Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2011, 306 (17): 1891-1901. 10.1001/jama.2011.1592.

Brewer JD, Christenson LJ, Weaver AL, Dapprich DC, Weenig RH, Lim KK, Walsh JS, Otley CC, Cherikh W, Buell JF, Woodle ES, Arpey C, Patton PR: Malignant melanoma in solid transplant recipients: collection of database cases and comparison with surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data for outcome analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2011, 147 (7): 790-796. 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.159.

Frankenthaler A, Sullivan RJ, Wang W, Renzi S, Seery V, Lee MY, Atkins MB: Impact of concomitant immunosuppression on the presentation and prognosis of patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2010, 20 (6): 496-500. 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32833e9f5b.

Le Mire L, Hollowood K, Gray D, Bordea C, Wojnarowska F: Melanomas in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2006, 154 (3): 472-477. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07094.x.

Veness MJ, Quinn DI, Ong CS, Keogh AM, Macdonald PS, Cooper SG, Morgan GW: Aggressive cutaneous malignancies following cardiothoracic transplantation: the Australian experience. Cancer. 1999, 85 (8): 1758-1764. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990415)85:8<1758::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-F.

Lévêque L, Dalac S, Dompmartin A, Louvet S, Euvrard S, Catteau B, Hazan M, Schollhamer M, Aubin F, Dreno B, Daguin P, Chevrant-Breton J, Frances C, Bismuth MJ, Tanter Y, Lambert D: Melanoma in organ transplant patients. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2000, 127 (2): 160-165.

Dapprich DC, Weenig RH, Rohlinger AL, Weaver AL, Quan KK, Keeling JH, Walsh JS, Otley CC, Christenson LJ: Outcomes of melanoma in recipients of solid organ transplant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008, 59 (3): 405-417. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.015.

Matin RN, Mesher D, Proby CM, McGregor JM, Bouwes Bavinck JN, del Marmol V, Euvrard S, Ferrandiz C, Geusau A, Hackethal M, Ho WL, Hofbauer GFL, Imko-Walczuk B, Kanitakis J, Lally A, Lear JT, Lebbe C, Murphy GM, Piaserico S, Seckin D, Stockfleth E, Ulrich C, Wojnarowska FT, Lin HY, Balch C, Harwood CA: Melanoma in organ transplant recipients: clinicopathological features and outcome in 100 cases. Am J Transplant. 2008, 8 (9): 1891-1900. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02326.x.

Miao Y, Everly JJ, Gross TG, Tevar AD, First MR, Alloway RR, Woodle ES: De novo cancers arising in organ transplant recipients are associated with adverse outcomes compared with the general population. Transplantation. 2009, 87 (9): 1347-1359. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a238f6.

Penn I: Malignant melanoma in organ allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1996, 61 (2): 274-278. 10.1097/00007890-199601270-00019.

Dinh QQ, Chong AH: Melanoma in organ transplant recipients: the old enemy finds a new battleground. Australas J Dermatol. 2007, 48 (4): 199-207. 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00387.x.

Chapman JR, Sheil AG, Disney AP: Recurrence of cancer after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001, 33 (1–2): 1830-1831.

Tsoka S, Ainali C, Karagiannis P, Josephs DH, Saul L, Nestle FO, Karagiannis SN: Toward prediction of immune mechanisms and design of immunotherapies in melanoma. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2012, 40 (4): 279-294. 10.1615/CritRevBiomedEng.v40.i4.40.

Strauss DC, Thomas JM: Transmission of donor melanoma by organ transplantation. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11 (8): 790-796. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70024-3.

Dillon P, Thomas N, Sharpless N, Collichio F: Regression of advanced melanoma upon withdrawal of immunosuppression: case series and literature review. Med Oncol. 2010, 27 (4): 1127-1132. 10.1007/s12032-009-9348-z.

Gogas H, Polyzos A, Kirkwood J: Immunotherapy for advanced melanoma: fulfilling the promise. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013, 39 (8): 879-85. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.04.006.

Otley CC, Hirose R, Salasche SJ: Skin cancer as a contraindication to organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005, 5 (9): 2079-2084. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01036.x.

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgements. There were no funding sources for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the design of the study. ED carried out the search. AWC completed the statistical analysis. All authors were involved with analysis and presentation of collected information. ED and AWC drafted the manuscript. ED composed Figure 1. AWC and ED composed Figure 2. ED drafted the tables. CAM and JK revised the manuscript, figures and tables. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahlke, E., Murray, C.A., Kitchen, J. et al. Systematic review of melanoma incidence and prognosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplant Res 3, 10 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-1440-3-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-1440-3-10