Abstract

Background

The hydrogen sulfide-releasing sildenafil, ACS6, has been demonstrated to inhibit superoxide formation through donating hydrogen sulfide (H2S). We have found that H2S antagonizes homocysteine-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. The aim of the present study is to explore the protection of ACS6 against homocysteine-triggered cytotoxicity and apoptosis and the molecular mechanisms underlying in PC12 cells.

Methods

Cell viability was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. Cell apoptosis was observed using the chromatin dye Hoechst 33258 and analyzed by Flow Cytometry after propidium iodide staining. Mitochondrial membrane potential was monitored using the fluorescent dye Rh123. Intracellular reactive oxygen species were determined by oxidative conversion of cell permeable 2',7'-dichlorfluorescein-diacetate to fluorescent 2',7'-dichlorfluorescein. The expression of cleaved caspase-3 and bcl-2 and the accumulation of cytosolic cytochrome cwere analyzed by Western blot.

Results

We show that ACS6 protects PC12 cells against cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by homocysteine and blocks homocysteine-triggered cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation. ACS6 treatment results in not only prevention of homocysteine-caused mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) loss and reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction but also reversal of Bcl-2 down-expression.

Conclusions

These results indicate that ACS6 protects PC12 cells against homocysteine-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis by preservation of mitochondrial function though inhibiting both loss of Δψ and accumulation of ROS as well as modulating the expression of Bcl-2. Our study provides evidence both for a neuroprotective effect of ACS6 and for further evaluation of ACS6 as novel neuroprotectants for Alzheimer's disease associated with homocysteine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Homocysteine, a thiol-containing amino acid, is a key metabolic intermediate in sulfuramino acid metabolism [1, 2]. Homocysteine not only can be remethylated to methionine by enzymes that require folic acid but also can be catabolized to form cysteine by cystathionine-β-synthetase (CBS). Both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that homocysteine is toxic to neuronal cells [3–9]. One explanation for the mechanism of homocysteine neurotoxicity is that auto-oxidation of homocysteine leads to the formation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide [10]. The causative link between hyperhomocysteinemia and neurodegeneration has been known [11]. Elevated brain homocysteine has been reported in Alzheimer's disease (AD) [12]. It is now established that elevated plasma homocysteine is a strong, independent risk factor of AD [13–17]. Therefore, the potential role of homocysteine is regarded as a novel therapeutic target for AD [17].

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a well-known toxic gas with the smell of rotten eggs, is formed naturally in mammalian tissues and exhibits a series of biological and physiological effects [18–21]. It has been recognized as an important endogenous neuromodulator [18, 22]. In the central nervous system, endogenous H2S is synthesized from L-cysteine and this process is predominantly catalyzed by CBS [19, 23]. The roles of H2S in neuroprotection have been extensively reported [21, 24]. H2S protects primary rat cortical neurons from oxytosis induced by glutamate [25] as well as SHSY-5Y cells against the neurotoxicity of peroxynitite (ONOO¯) [26] and hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [27]. We also have reported that H2S produces neuroprotective effects when it is used to treat beta-amyloid- and 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridium ion (MPP+)-induced neurotoxicity [28–30]. Most recent study by our group have demonstrated that H2S protects neurons from damage caused by homocysteine to neurons [31], suggesting a promising role of H2S supplement as a novel therapeutic strategy for AD associated with homocysteine.

The pharmacological profile of a new, safe and effective H2S-releasing sildenafil (ACS6) was described recently [32]. Muzaffar et al. reported that ACS6 is a potent inhibitor of superoxide formation and that H2S release from ACS6 is crucial for its biological actions [32]. Thus, it is logical to test the role of ACS6 in homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity.

The purpose of this study therefore is to investigate the effects of ACS6 on homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity to PC12 cells, a clonal rat pheochromocytoma cell line, which is widely used for studying the cellular biology of neurons (33-35). We demonstrated for the first time that ACS6, a putative H2S-donating derivative of sildenafil, significantly protected PC12 cells against homocysteine-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis by inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) and up-regulation of bcl-2 expression. Our findings suggest that ACS6, acting as an H2S donor, is able to act as a neuroprotectant.

Materials and methods

Materials

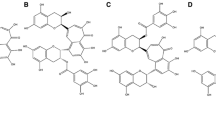

Hoechst 33258, Rhodamine 123 (Rh123), 2',7'-dichlorfluorescein- diacetate (DCFH-DA) and homocysteine were purchased from Sigma Chemical CO (st.Louis, MO, USA). ACS6, 1-Piperazineacetic acid 4-[[3-(4,7-dihydro-1-methyl-7-oxo-3-propyl-1H-pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)-4- ethoxyphenyl]sulphonyl]-,4-(3-thioxo-3H-1,2-dithiol-5-yl)phenyl ester, was supplied by CTG Pharma, Milan, Italy (The chemical structure of ACS6 is shown in Figure 1). Cell counter kit-8 (CCK-8) was bought from Dojindo Lab. (Rockville, MD, USA). Antibodies for detecting bcl-2 and cleaved caspase-3 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibody against cytochrome c (Cyt-c) was purchased from Abcam Technology (Cambridge, CB, UK). RPMI-1640 medium, horse serum and fetal bovine serum were supplied by Gibico BRL (Ground Island, NY, USA).

Cell culture

PC12 cells, a rat cell line derived from a Pheochromocytoma cells, were supplied from Sun Yat-sen University Experimental Animal Center (Guangzhou, China), and were maintained on tissue culture plastic in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2and 95% air. The culture media was changed three times per week.

Determination of cell viability

The viability of PC12 cells was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. PC12 cells were cultured in 96-well plates at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2and 95% air. When the cells were about 70% fusion, indicated conditioned-mediums were administered. At the end of treatment, 10 μl CCK-8 solutions were added into each well and then the plates were incubated for 3 h in the incubator. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Means of four wells optical density (OD) in the indicated groups were used to calculate the percentage of cell viability according to the formula below: cell viability (%) = OD treatment group/OD control group × 100%. The experiment was repeated three times.

Nuclear staining for assessment of apoptosis

Chromosomal condensation and morphological changes in the nucleus of PC12 cells were observed using the chromatin dye Hoechst 33258. The PC12 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min. After three rinses with PBS, the cells were stained with 5 mg/L Hoechst 33258 for 10 min. Slides were rinsed briefly with PBS, air dried, then mounted in an anti-fluorescein fading medium (Perma Fluor, Immunon, PA, USA). Slides were visualized under a fluorescent microscope (BX50-FLA, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Viable cells displayed normal nuclear size and uniform fluorescence, whereas apoptotic cells showed condensed nuclei or nuclear condensations. The percentage of apoptotic cells was evaluated as follows: The percentage of apoptotic cells = The numbers of apoptotic cells/(The numbers of apoptotic cells + The numbers of viable cells) × 100%.

Measurement of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ)

Δψ was monitored using the fluorescent dye Rh123, a cell permeable cationic dye, which preferentially enters into mitochondria based on the highly negative Δψ. Depolarization of Δψ results in the loss of Rh123 from the mitochondria and a decrease in intracellular fluorescence [36]. Rh123 (100 μg/L) was added to cell cultures for 45 min at 37°C. Rh123 fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry (FCM, Beckman-coulter Co., USA). Ten thousand cells per sample were analyzed and the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) in the positive cells represents the level of Δψ.

Measurement of intracellular ROS generation

Intracellular ROS were determined by oxidative conversion of cell permeable 2',7'-dichlorfluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) to fluorescent 2',7'-dichlorfluorescein (DCF) [37, 38]. The cells were collected by pipetting and were washed one time with PBS. After DCFH-DA (2.5 μM) was added to cell cultures for 20 min at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with PBS. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of the positive cells in ten thousand cells per sample was measured by FCM, and the MFI represents the amount of ROS.

Western blot analysis for cleaved caspase-3 and bcl-2

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was carried out on 5% stacking and 12% resolving gel with low range molecular weight standards (Solarbio, China). Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane with loading buffer (Beyotime, China) containing 0.1 M Tris (pH6.8), 20% glycerol, 10% mercaptoethanol, 4% SDS and 0.2% Bromophenol Blue. Samples were heated at 100°C for 5 min before gel loading. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a PVDF transfer membrane (Solarbio, China). After this, the membranes were blocked with TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% BSA (Sigma, USA) for 2 h. Following this, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 at 4°C over night. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG labeled with horseradish peroxidase (Zsbio, China) diluted at 1:1000 at room temperature for 2 h. The membranes were washed again and developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL, Zsbio, China) followed by apposition of the membranes with autoradiographic films (Kodak, China). The integrated optical density for the protein band was calculated by Image-J software.

Analysis of Cytosolic Cytochrome cAccumulation

Cytochrome crelease from mitochondria into the cytosol was measured by Western blot analysis. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 200gfor 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were then washed twice with chilled PBS and added with 400 μl of lysis buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM Na-EGTA, 1.5 mM Na-EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Shanghai, China). After incubation on ice for 5 min, the cells were gently scraped off and centrifuged at 1000gfor 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were further centrifuged at 16,000gfor 25 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was used as the soluble cytosolic fraction and subjected to Western blot analysis as mentioned above.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The significance of inter-group differences was evaluated by one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA: Least-significant difference's test for post hoc comparisons). Differences were considered significant at P< 0.05.

Results

ACS6 suppresses homocysteine-induced cytotoxicity

To investigate the effect of ACS6 on homocysteine-induced cytotoxicity, cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8 assay. As shown in Figure 2A, treatment with homocysteine (5 mmol/L) for 24 h significantly attenuated cell viability and the cytotoxic effect of homocysteine on PC12 cells was blocked by pretreatment with ACS6 at the concentrations of 4, 8, and 16 μmol/L for 30 min in a concentration-dependent manner. ACS6 (from 4 μmol/L to 16 μmol/L) alone did not measurably affect the viability of PC12 cells (Figure 2B). These results indicate that ACS6 protects PC12 cells against homocysteine-caused cytotoxicity.

ACS6 protects PC12 cells against homocysteine-induced cytotoxicity. (A) PC12 cells were pretreated with ACS6 (4, 8, or 16 μmol/L) for 30 min and then exposed to homocysteine (Hcy, 5 mmol/L) for 24 h. (B) PC12 cells were treated with 4, 8, and 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 3). ***P< 0.001, versus control group; #P< 0.05, ##P< 0.01, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine-treated alone group.

ACS6 inhibits homocysteine-induced apoptosis

The nuclear staining assay was used to assess the morphological changes of apoptosis in PC12 cells. As illustrated in Figure 3, the untreated cells and the cells treated with 16 μmol/L ACS exhibited uniformly dispersed chromatin and intact cell membrane. On the other hand, the homocysteine-treated cells (5 mmol/L, for 24 h) appeared typical characteristics of apoptosis, including apoptotic nuclear condensation. When PC12 cells were pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6, however, the number of cells with nuclear condensation induced by 24 h exposure to 5 mmol/L homocysteine was significantly reduced, suggesting that ACS6 protects PC12 cells against apoptosis induced by homocysteine.

Nuclear staining to evaluate the anti-apoptotic effect of ACS6. After pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 30 min, PC12 cells were exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Hcy) for 24 h and incubated with 5 mg/L Hoechst 33258 for 30 min. (A) Representative morphology visualized under a fluorescence microscope (10 × objective, BX50-FLA, Olympus). Cells with brightly fluorescent and fragmented nuclei were apoptotic. (B) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cells. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 5). ***P< 0.001, versus control group; ###P< 0.001, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine-treated alone group.

ACS6 decreases homocysteine-induced release of Cyt-c

We examined the effect of ACS6 on the release of Cyt-c in homocysteine-stimulated PC12 cells by Western blot analysis. As illustrated in Figure 4, treatment with homocysteine (5 mmol/L) for 24 h significantly promoted the release of Cyt-c in PC12 cells. However, the homocysteine-induced release of Cyt-c was significantly attenuated by pretreatment with ACS6 (16 μmol/L, 30 min). These results indicate that ACS6 prevents homocysteine-induced Cyt-c release.

Effects of ACS6 on the release of Cyt-c in PC12 cells. After pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 30 min, PC12 cells were exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Hcy) for 24 h. A, representative immunoblots for Cyt-c release from three independent experiments. Cytosolic fractions of the extract were subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-Cyt-c antibody. In all blots, staining for β-actin was used as a loading control. B, quantification of cytosolic Cyt-c accumulation as a percent of the control. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 3). ***P <0.001, versus control; #P< 0.05, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine-treated alone group.

ACS6 reduces homocysteine-induced activation of caspase-3

To investigate whether ACS6 modulates homocysteine-induced activation of caspase-3, the levels of caspase-3 activation were measured by Western blot analysis using anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody. As illustrated in Figure 5, exposure to homocysteine (5 mmol/L, 24 h) significantly enhanced the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in PC12 cells. However, the homocysteine-induced enhancement of cleaved caspase-3 expression was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with ACS6 (16 μmol/L, 30 min). These results indicate that ACS6 blocks the homocysteine-induced activation of caspase-3.

Effects of ACS6 on the activation of caspase-3 in PC12 cells. After pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 30 min, PC12 cells were exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Hcy) for 24 h. The activation of caspase-3 in PC12 cells was analyzed by Western blot using an anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody. Western blot images show representative results from three independent experiments. In all blots, staining for β-actin was used as a loading control. The level of cleaved caspase-3 expression obtained in each experimental condition was calculated as a fold of the control. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 3). ***P <0.001, versus control; ###P< 0.001, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine-treated alone group.

ACS6 attenuates homocysteine-induced accumulation of intracellular ROS

As the cytotoxicity of homocysteine is mainly mediated by oxidative stress [10, 39], we investigated the effect ACS6 on homocysteine-induced ROS formation by using DCFH-DA staining. Compared with non-treated control cells, the level of intracellular ROS was increased in PC12 cells treated with 5 mmol/L homocysteine for 24 h, as shown by the increase in the MFI of DCF quantified by FCM analysis (Figure 6A, B). However, when PC12 cells were co-treated with ACS6 (16 μmol/L), the MFI of DCF (Figure 6A, B) in PC12 cells exposed to homocysteine (5 mmol/L, 24 h) were significantly decreased, suggesting that homocysteine-induced intracellular ROS accumulation is attenuated by ACS6. The cells treated with ACS6 (16 μmol/L) alone showed weak DCF fluorescence similar to that in the vehicle control (Figure 6).

Effects of ACS6 on homocysteine-exerted accumulation of intracellular ROS in PC12 cells. After pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 30 min, PC12 cells were exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Hcy) for 24 h and stained with DCFH-DA for 20 min. The changes of ROS in different treatment groups were quantified by fluorescent sorting FCM analysis (A, B). (A) Representative histogram of DCF-derived fluorescence in PC12 cells exposed to different treatments measured by FCM. (B) Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DCF measured by FCM. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 3). ***P <0.001, versus control; ###P< 0.001, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine- treated alone group.

ACS6 prevents homocysteine-induced dissipation of Δψ

Dissipation of Δψ is a critical event in the process of apoptosis [40]. To examine whether the anti-apoptotic effect of ACS6 involves preservation of Δψ, we used Rh123 staining to assess the level of Δψ in PC12 cells. After 24 h exposure to 5 mmol/L homocysteine, the Δψ was obviously reduced, as shown by the decrease in the MFI of Rh123 quantified by FCM analysis (Figure 7A, B), compared with non-treated control cells. Although ACS6 exposure alone (16 μmol/L) has no effect on Δψ of PC12 cells, the cells pretreated with ACS6 (16 μmol/L) for 30 min enhanced the intensity of Rh123 fluorescence in PC12 cells treated with homocysteine (5 mmol/L) for 24 h (Figure 7A, B). These results suggested that homocysteine-induced dissipation of Δψ is inhibited by ACS6.

Effects of ACS6 on homocysteine-induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) in PC12 cells. After pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 30 min, PC12 cells were exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Hcy) for 24 h and stained with Rh123 for 20 min. The changes of Δψ in different treatment groups were quantified by fluorescent sorting FCM analysis. (A) Representative histogram of Rh123-derived fluorescence in PC12 cells exposed to different treatments measured by FCM. (B) Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Rh123 measured by FCM. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 3). **P <0.01, versus control; ##P< 0.01, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine-treated alone group.

ACS6 reverses homocysteine-induced down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression

Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein. To explore whether ACS6 modulates the effect of homocysteine on bcl-2 expression, the levels of bcl-2 were measured by Western blot analysis. As illustrated in Figure 8, exposure to homocysteine (5 mmol/L, 24 h) significantly reduced the expression of Blc-2 in PC12 cells. However, the homocysteine-induced decrease of Bcl-2 expression was significantly abolished by pretreatment with ACS6 (16 μmol/L, 30 min). These results indicate that ACS6 blocks the homocysteine-induced down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression.

Effects of ACS6 on the expression of Bcl-2 in PC12 cells. After pretreated with 16 μmol/L ACS6 for 30 min, PC12 cells were exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Hcy) for 24 h. The levels of Bcl-2 expression in PC12 cells were determined by Western blot using an anti-Bcl-2 antibody. Western blot images show representative results from three independent experiments. In all blots, staining for β-actin was used as a loading control. The level of Bcl-2 expression obtained in each experimental condition was calculated as a fold of the control. Values are the mean ± SEM (n= 3). **P <0.01, versus control; #P< 0.05, versus 5 mmol/L homocysteine-treated alone group.

Discussion

Homocysteine is known to induce neurotoxicity and apoptosis [6, 8] and cause oxidative damage [41]. Our previous results have demonstrated that homocysteine inhibits the activity and expression of CBS and the endogenous production of H2S in PC12 cells and this inhibitory effect contribute to the neurotoxicity of homocysteine [42]. We also found that H2S acts as a neuroprotectant counteracting an oxidative insult to neurons induced by homocysteine [31]. It has been shown that ACS6 inhibits the formation of superoxide by releasing H2S [32]. Therefore, we investigated whether ACS6 has the ability to attenuate the neurotoxicity of homocysteine.

PC12 cells, originally derived from a transplantable rat pheochromocytoma, are accepted as a model system for primary neuronal cells because of their ability to respond to nerve growth factor [43]. In the present study, we determined the neuroprotective effects of ACS6 on homocysteine neurotoxicity and the underlying mechanisms by studying PC12 cells. Similar to the findings by Linnebank et al.[9], we found that exposure of PC12 cells to homocysteine resulted in decrease of viability as well as increase of apoptotic cells. Furthermore, Cyt-c release and caspase-3 activation occurred in response to homocysteine in PC12 cells. These results indicated that homocysteine induces significant neurotoxicity and apoptosis in PC12 cell. Of important, the present work demonstrated that ACS6 not only attenuated the cytotoxicity and the apoptotic cells induced by homocysteine but also inhibited homocysteine-triggered Cyt-c release and caspase-3 activation in PC12 cells. This study is therefore the first to conclude that treatment with ACS6 blunts the apoptosis induced by homocysteine in PC12 cells.

It is well known that mitochondrial dysfunction is an important feature in apoptosis [44] as well as a prominent factor associated with cell death and some models of apoptosis [40]. Mitochondrial damage is consistent with intracellular ROS production and changes in Δψ during apoptosis [45]. Δψ has been shown to be involved in a variety of pathophysiological conditions, in particular for apoptosis [46, 47]. ROS is responsible for the homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity [10, 39]. Overproduction of ROS may result in mitochondrial dysfunction, causing Δψ loss and promoting Cyt-c release and caspase-3 activation, which ultimately cause cell apoptosis [48]. To investigate the mechanisms of the cytoprotective effect of ACS6 on homocysteine-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells, we examined its effects on the homocysteine-mediated changes in ROS and Δψ. The overproduction of ROS and dissipation of Δψ were significantly induced in homocysteine-exposed PC12 cells, while pretreatment with ACS6 prevented both phenomena. Our results suggested that the anti-apoptotic effect of ACS6 is associated with the preservation of mitochondrial function by blocking the dissipation of Δψ and the increase in ROS level.

It has been shown that Bcl-2 prevents apoptosis by regulating an antioxidant pathway [49]. Kane, et al.reported that bcl-2 inhibits neural death by reducing the generation of ROS [50]. Additionally, over-expression of bcl-2 increases stability of Δψ [51], and blocks cytochrome C release from mitochondria prior to mitochondrial membrane depolarization by preventing mitochondrial pore opening [52]. It is therefore established that the cytoprotective effects associated with decrease in ROS generation and stability of Δψ may be the results of over-expressed bcl-2. In the present study, we revealed that ACS6 blocked the down-regulation of bcl-2 induced by homocysteine. This finding implied that ACS6-induced up-regulation of bcl-2 expression may be involved in the protective actions of ACS6 against homocysteine-induced apoptosis and neurotoxicity.

In summary, our data for the first time demonstrated that ACS6 significantly limits the decrease in viability as well as the increase in apoptotic cells induced by homocysteine and prevents homocysteine-triggered Cyt-c release and caspase-3 activation. ACS6 not only blocks the loss of Δψ and overproduction of ROS caused by homocysteine but also upregulates the down-expression of Bcl-2 occurred in response to homocysteine. The findings support that ACS6 protects PC12 cells against homocysteine induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis and the underlying mechanism may involve preservation of mitochondrial function by inhibiting both loss of Δψ and accumulation of ROS as well as up-regulating the expression of bcl-2.

ACS6 is a putative H2S-donating derivative of sildenafil. It has been reported that H2S release from ACS6 is crucial for its biological action that inhibits the formation of superoxide [32]. In recent years, it has become clear that protects neurons from oxidative stress by increasing the levels of GSH [25, 53] and attenuate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preserving mitochondrial function [54]. It is worthy to note that a previous study reported that H2S was detrimental in cerebral ischemia in rats [55]. This finding suggested that H2S is protective at concentrations that are equivalent to normal physiological concentrations, but is deleterious at supraphysiological concentrations in the brain. This is also supported by the data that excessive inhibition of H2S by AOAA led to detrimental effects in the brain [55]. Therefore, the ability of H2S to regulate cell viability may be concentration and time dependent. At low concentrations, as may occur in physiological conditions, cells remain unscathed by H2S, but, at high concentrations, as may occur in pathological states, a cytotoxic/proapoptotic effect becomes evident. To date, H2S-releasing "drugs" used in biological experiments has been largely restricted to simple sulfide salts, most commonly sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), which releases H2S instantaneously in aqueous solution. However, the release of endogenous H2S from cells is likely to occur in lesser amounts and at a much slower rate than that from sulfide salts, and therefore NaHS may not mimic the biological effects of naturally produced H2S [56]. Muzaffar et al. reported that once taken up by cells, ACS6 would release H2S intracellularly and in a long-lasting controlled way [32]. Large amounts of H2S released over a short time frame by NaHS may trigger signaling pathways resulting in cell death, whereas this does not occur with the slower but sustained release of lower amounts of H2S from ACS6.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present findings clearly identify that ACS6, a novel H2S-releasing derivative, provides significant protection against homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity to PC12 cells by inhibiting both loss of Δψ and accumulation of ROS and up-regulating the expression of bcl-2. Based on the notion that elevated plasma homocysteine is a strong, independent risk factor of AD [13–17], our present study indicates that ASC6, or perhaps alternative related H2S-releasing compounds, could be worth to be further investigated in the study for their therapeutic uses as novel neuroprotectants for AD associated with homocysteine.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer's disease

- CBS:

-

cystathionine-β-synthetase

- Cyt-c:

-

cytochrome c

- DCFH-DA 2':

-

7':-dichlorfluorescein- diacetate

- DCF 2':

-

7':-dichlorfluorescein

- FCM:

-

flow cytometric

- H2S:

-

Hydrogen sulfide

- MFI:

-

mean fluorescent intensity

- Δψ:

-

mitochondrial membrane potential

- PI:

-

propidium iodide

- Rh123:

-

Rhodamine 123

- ROS:

-

reactive oxygen species

References

Prudova A, Bauman Z, Braun A, Vitvitsky V, Lu SC, Banerjee R: S-adenosylmethionine stabilizes cystathionine beta-synthase and modulates redox capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103 (17): 6489-94. 10.1073/pnas.0509531103.

Selhub J: Homocysteine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999, 19: 217-46. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217.

Lipton SA, Kim WK, Choi YB, Kumar S, D'Emilia DM, Rayudu PV, et al: Neurotoxicity associated with dual actions of homocysteine at the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94 (11): 5923-8. 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5923.

Parsons RB, Waring RH, Ramsden DB, Williams AC: In vitro effect of the cysteine metabolites homocysteic acid, homocysteine and cysteic acid upon human neuronal cell lines. Neurotoxicology. 1998, 19 (4-5): 599-603.

Kim JP, Koh JY, Choi DW: L-homocysteate is a potent neurotoxin on cultured cortical neurons. Brain Res. 1987, 437 (1): 103-10. 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91531-9.

Kruman II, Culmsee C, Chan SL, Kruman Y, Guo Z, Penix L, et al: Homocysteine elicits a DNA damage response in neurons that promotes apoptosis and hypersensitivity to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000, 20 (18): 6920-6.

Ho PI, Ortiz D, Rogers E, Shea TB: Multiple aspects of homocysteine neurotoxicity: glutamate excitotoxicity, kinase hyperactivation and DNA damage. J Neurosci Res. 2002, 70 (5): 694-702. 10.1002/jnr.10416.

Baydas G, Reiter RJ, Akbulut M, Tuzcu M, Tamer S: Melatonin inhibits neural apoptosis induced by homocysteine in hippocampus of rats via inhibition of cytochrome c translocation and caspase-3 activation and by regulating pro- and anti-apoptotic protein levels. Neuroscience. 2005, 135 (3): 879-86. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.048.

Linnebank M, Lutz H, Jarre E, Vielhaber S, Noelker C, Struys E, et al: Binding of copper is a mechanism of homocysteine toxicity leading to COX deficiency and apoptosis in primary neurons, PC12 and SHSY-5Y cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2006, 23 (3): 725-30. 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.010.

White AR, Huang X, Jobling MF, Barrow CJ, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, et al: Homocysteine potentiates copper- and amyloid beta peptide-mediated toxicity in primary neuronal cultures: possible risk factors in the Alzheimer's-type neurodegenerative pathways. J Neurochem. 2001, 76 (5): 1509-20. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00178.x.

van den Berg M, van der Knaap MS, Boers GH, Stehouwer CD, Rauwerda JA, Valk J: Hyperhomocysteinaemia; with reference to its neuroradiological aspects. Neuroradiology. 1995, 37 (5): 403-11.

Eto K, Asada T, Arima K, Makifuchi T, Kimura H: Brain hydrogen sulfide is severely decreased in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002, 293 (5): 1485-8. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00422-9.

Van Dam F, Van Gool WA: Hyperhomocysteinemia and Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009, 48 (3): 425-30. 10.1016/j.archger.2008.03.009.

Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, D'Agostino RB, et al: Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346 (7): 476-83. 10.1056/NEJMoa011613.

Miller JW: Homocysteine and Alzheimer's disease. Nutr Rev. 1999, 57 (4): 126-9.

Clarke R, Smith AD, Jobst KA, Refsum H, Sutton L, Ueland PM: Folate, vitamin B12, and serum total homocysteine levels in confirmed Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998, 55 (11): 1449-55. 10.1001/archneur.55.11.1449.

Dwyer BE, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA: Homocysteine and Alzheimer's disease: a modifiable risk?. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004, 36 (11): 1471-5. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.009.

Kimura H: Hydrogen sulfide as a neuromodulator. Mol Neurobiol. 2002, 26 (1): 13-9. 10.1385/MN:26:1:013.

Wang R: Two's company, three's a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter?. FASEB J. 2002, 16 (13): 1792-8. 10.1096/fj.02-0211hyp.

Lowicka E, Beltowski J: Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) - the third gas of interest for pharmacologists. Pharmacol Rep. 2007, 59 (1): 4-24.

Szabo C: Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007, 6 (11): 917-35. 10.1038/nrd2425.

Tan BH, Wong PT, Bian JS: Hydrogen sulfide: a novel signaling molecule in the central nervous system. Neurochem Int. 2010, 56 (1): 3-10. 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.08.008.

Moore PK, Bhatia M, Moochhala S: Hydrogen sulfide: from the smell of the past to the mediator of the future?. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003, 24 (12): 609-11. 10.1016/j.tips.2003.10.007.

Qu K, Lee SW, Bian JS, Low CM, Wong PT: Hydrogen sulfide: neurochemistry and neurobiology. Neurochem Int. 2008, 52 (1-2): 155-65. 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.05.016.

Kimura Y, Kimura H: Hydrogen sulfide protects neurons from oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2004, 18 (10): 1165-7.

Whiteman M, Armstrong JS, Chu SH, Jia-Ling S, Wong BS, Cheung NS, et al: The novel neuromodulator hydrogen sulfide: an endogenous peroxynitrite 'scavenger'?. J Neurochem. 2004, 90 (3): 765-8. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02617.x.

Whiteman M, Cheung NS, Zhu YZ, Chu SH, Siau JL, Wong BS, et al: Hydrogen sulphide: a novel inhibitor of hypochlorous acid-mediated oxidative damage in the brain?. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005, 326 (4): 794-8. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.110.

Tang XQ, Fan LL, Li YJ, Shen XT, Zhuan YY, He JQ, et al: Inhibition of hydrogen sulfide generation contributes to 1-methy-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced neurotoxicity. Neurotox Res. 2011, 19 (3): 403-11. 10.1007/s12640-010-9180-4.

Tang XQ, Yang CT, Chen J, Yin WL, Tian SW, Hu B, et al: Effect of hydrogen sulphide on beta-amyloid-induced damage in PC12 cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008, 35 (2): 180-6.

Yin WL, He JQ, Hu B, Jiang ZS, Tang XQ: Hydrogen sulfide inhibits MPP(+)-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Life Sci. 2009, 85 (7-8): 269-75. 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.05.023.

Tang XQ, Shen XT, Huang YE, Ren YK, Chen RQ, Hu B, et al: Hydrogen sulfide antagonizes homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Neurosci Res. 2010, 68 (3): 241-9. 10.1016/j.neures.2010.07.2039.

Muzaffar S, Jeremy JY, Sparatore A, Del Soldato P, Angelini GD, Shukla N: H2S-donating sildenafil (ACS6) inhibits superoxide formation and gp91phox expression in arterial endothelial cells: role of protein kinases A and G. Br J Pharmacol. 2008, 155 (7): 984-94.

Li R, Kong Y, Ladisch S: Nerve growth factor-induced neurite formation in PC12 cells is independent of endogenous cellular gangliosides. Glycobiology. 1998, 8 (6): 597-603. 10.1093/glycob/8.6.597.

Wang S, Hu CP, Jiang DJ, Peng J, Zhou Z, Yuan Q, et al: All-trans retinoic acid inhibits cobalt chloride-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells: role of the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase/asymmetric dimethylarginine pathway. J Neurosci Res. 2009, 87 (8): 1938-46. 10.1002/jnr.21999.

Duan WG, Shang J, Jiang ZZ, Yao JC, Yun Y, Yan M, et al: Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 down-regulates norepinephrine synthesis and release in PC12 cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009, 104 (6): 434-40. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00314.x.

Mattson MP, Zhang Y, Bose S: Growth factors prevent mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of calcium homeostasis, and cell injury, but not ATP depletion in hippocampal neurons deprived of glucose. Exp Neurol. 1993, 121 (1): 1-13. 10.1006/exnr.1993.1066.

Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Ames BN: Detection of picomole levels of hydroperoxides using a fluorescent dichlorofluorescein assay. Anal Biochem. 1983, 134 (1): 111-6. 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90270-1.

Grieve A, Butcher SP, Griffiths R: Synaptosomal plasma membrane transport of excitatory sulphur amino acid transmitter candidates: kinetic characterisation and analysis of carrier specificity. J Neurosci Res. 1992, 32 (1): 60-8. 10.1002/jnr.490320108.

Ho PI, Collins SC, Dhitavat S, Ortiz D, Ashline D, Rogers E, et al: Homocysteine potentiates beta-amyloid neurotoxicity: role of oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2001, 78 (2): 249-53. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00384.x.

Petronilli V, Penzo D, Scorrano L, Bernardi P, Di Lisa F: The mitochondrial permeability transition, release of cytochrome c and cell death. Correlation with the duration of pore openings in situ J Biol Chem. 2001, 276 (15): 12030-4.

Yan SK, Chang T, Wang H, Wu L, Wang R, Meng QH: Effects of hydrogen sulfide on homocysteine-induced oxidative stress in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006, 351 (2): 485-91. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.058.

Tang XQ, Shen XT, Huang YE, Chen RQ, Ren YK, Fang HR, et al: Inhibition of Endogenous Hydrogen Sulfide Generation is Associated with Homocysteine-Induced Neurotoxicity: Role of ERK1/2 Activation. J Mol Neurosci. 2010

Greene LA, Tischler AS: Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976, 73 (7): 2424-8. 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424.

Lemasters JJ, Qian T, He L, Kim JS, Elmore SP, Cascio WE, et al: Role of mitochondrial inner membrane permeabilization in necrotic cell death, apoptosis, and autophagy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002, 4 (5): 769-81. 10.1089/152308602760598918.

Kim WH, Park WB, Gao B, Jung MH: Critical role of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial membrane potential in Korean mistletoe lectin-induced apoptosis in human hepatocarcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2004, 66 (6): 1383-96. 10.1124/mol.104.001347.

Fiskum G, Starkov A, Polster BM, Chinopoulos C: Mitochondrial mechanisms of neural cell death and neuroprotective interventions in Parkinson's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003, 991: 111-9.

Knott AB, Perkins G, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy-Wetzel E: Mitochondrial fragmentation in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008, 9 (7): 505-18.

Orrenius S: Reactive oxygen species in mitochondria-mediated cell death. Drug Metab Rev. 2007, 39 (2-3): 443-55. 10.1080/03602530701468516.

Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ: Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993, 75 (2): 241-51. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-N.

Kane DJ, Sarafian TA, Anton R, Hahn H, Gralla EB, Valentine JS, et al: Bcl-2 inhibition of neural death: decreased generation of reactive oxygen species. Science. 1993, 262 (5137): 1274-7. 10.1126/science.8235659.

Wu LY, Ding AS, Zhao T, Ma ZM, Wang FZ, Fan M: Involvement of increased stability of mitochondrial membrane potential and overexpression of Bcl-2 in enhanced anoxic tolerance induced by hypoxic preconditioning in cultured hypothalamic neurons. Brain Res. 2004, 999 (2): 149-54. 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.081.

Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai J, et al: Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997, 275 (5303): 1129-32. 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129.

Kimura Y, Goto Y, Kimura H: Hydrogen sulfide increases glutathione production and suppresses oxidative stress in mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010, 12 (1): 1-13. 10.1089/ars.2008.2282.

Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, et al: Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104 (39): 15560-5. 10.1073/pnas.0705891104.

Qu K, Chen CP, Halliwell B, Moore PK, Wong PT: Hydrogen sulfide is a mediator of cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke. 2006, 37 (3): 889-93. 10.1161/01.STR.0000204184.34946.41.

Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, Neo KL, Cheng Y, Lee SW, et al: Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2008, 117 (18): 2351-60. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.753467.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (81071005, 30770740) and the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry ([2010]508).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr P Del Soldato is a shareholder of CTG Pharma, Milan, Italy. This company has patents on reagents used in this study. Professor Xiao-Qing Tang received a grant from CTG Pharma.

Authors' contributions

XQT and RQC designed and developed this study. YKR, YYZ, HRF and CYW conducted experiments, analyzed data and coordinated the study. XQT wrote the manuscript. PDS and AS designed ASC6 and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Xiao-Qing Tang, Rong-Qian Chen contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, XQ., Chen, RQ., Ren, YK. et al. ACS6, a Hydrogen sulfide-donating derivative of sildenafil, inhibits homocysteine-induced apoptosis by preservation of mitochondrial function. Med Gas Res 1, 20 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-9912-1-20

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-9912-1-20