Abstract

Background

Approximately 10% of Lynch syndrome families have a mutation in MSH6 and fewer families have a mutation in PMS2. It is assumed that the cancer incidence is the same in families with mutations in MSH6 as in families with mutations in MLH1/MSH2 but that the disease tends to occur later in life, little is known about families with PMS2 mutations. This study reports on our findings on mutation type, cancer risk and age of diagnosis in MSH6 and PMS2 families.

Methods

A total of 78 participants (from 29 families) with a mutation in MSH6 and 7 participants (from 6 families) with a mutation in PMS2 were included in the current study. A database of de-identified patient information was analysed to extract all relevant information such as mutation type, cancer incidence, age of diagnosis and cancer type in this Lynch syndrome cohort. Cumulative lifetime risk was calculated utilising Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

Results

MSH6 and PMS2 mutations represent 10.3% and 1.9%, respectively, of the pathogenic mutations in our Australian Lynch syndrome families. We identified 26 different MSH6 and 4 different PMS2 mutations in the 35 families studied. We report 15 novel MSH6 and 1 novel PMS2 mutations. The estimated cumulative risk of CRC at age 70 years was 61% (similar in males and females) and 65% for endometrial cancer in MSH6 mutation carriers. The risk of developing CRC is different between males and females at age 50 years, which is 34% for males and 21% for females.

Conclusion

Novel MSH6 and PMS2 mutations are being reported and submitted to the current databases for identified Lynch syndrome mutations. Our data provides additional information to add to the genotype-phenotype spectrum for both MSH6 and PMS2 mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)/Lynch syndrome (MIM 120435) accounts for approximately 2 percent of all diagnosed colorectal cancers (CRC) [1]. Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominantly inherited cancer syndrome characterised by early onset epithelial cancers. Patients with Lynch syndrome have an increased risk of developing malignancies during their lifetime, at a mean age of disease onset that is significantly lower than that observed in the general population. In addition to the high risk of developing CRC, Lynch syndrome patients are also at risk of developing malignancies in a variety of organs that include the uterus, small bowel, stomach, ovary, bladder, pancreas and the urinary tract [2, 3]. A breakdown in the fidelity of DNA mismatch repair has been shown to be the basis of the disease. At present four genes encoding proteins that are integrally involved in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) have been clearly associated with Lynch syndrome and these are MLH1 (MIM 120436), MSH2 (MIM 609309), MSH6 (MIM 600678) and PMS2 (MIM 600259) [4–7]. MMR provides several genetic stabilisation functions; it corrects DNA biosynthesis errors, ensures the fidelity of genetic recombination and participates in the earliest steps of cell cycle checkpoint/control and apoptotic responses [8]. MMR gene defects increase the risk of malignant transformation of cells, which ultimately result in the disruption of one or several genes associated with epithelial integrity [8, 9].

Genetic testing of MLH1 and MSH2 for Lynch Syndrome has been available for over a decade and during this time significant advances in the technologies used for diagnosis have occurred. Together with improvements in technology the ability to rapidly screen additional genes associated with Lynch syndrome, MSH6 and PMS2, has become available. The MMR genes MSH6 and PMS2 have been shown to interact with MSH2 and MLH1, respectively [9, 10]. Impediments to screening these two genes for mutations have been the high cost of testing and the presence of pseudogenes in PMS2 [11–13]. Notwithstanding, some information is available with respect to the frequency of MSH6 and PMS2 mutations but there is relatively limited information available regarding the spectrum of disease, especially in Australian Lynch syndrome families harbouring deleterious changes in one of these two genes.

Approximately 10 percent of Lynch syndrome families have a mutation in MSH6 and fewer families have a mutation in PMS2 [14]. It is assumed that the cancer incidence is the same in families with mutations in MSH6 as in families with mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 but that disease tends to occur later in life as a result of the partial compensation provided by MSH3 in MMR [15]. PMS2 mutations lead to an attenuated phenotype with weaker family history and older ages of disease onset [15]. Phenotype information for MSH6 and PMS2 mutation carriers is therefore of great interest for the recognition of Lynch syndrome and the formulation of sufficient surveillance schemes.

In the current study we report on our findings on mutation type, cancer risk and age of diagnosis in 29 families (78 participants) with a mutation in MSH6 and 6 families (7 participants) with a mutation in PMS2.

Materials and methods

All the participants selected for this study had previously been diagnosed with Lynch syndrome and harboured a mutation in either MSH6 or PMS2. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was obtained from Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Since 1997, samples have been tested for Lynch syndrome/HNPCC at the Division of Genetics, Hunter Area Pathology Service in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. Information from all the samples collected between 1997 and 2008 has been placed into a database. The families were referred for genetic testing due to a clinical diagnosis of HNPCC according to the Amsterdam II criteria/Bethesda criteria or due to the tumour displaying microsatellite instability (MSI) or immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrating loss of MSH6/PMS2 expression.

A total of 78 participants (from 29 Caucasian families) with a mutation in MSH6 and 7 participants (from 6 Caucasian families) with a mutation in PMS2 were included in the current study. A database of de-identified patient information was analysed to extract all relevant information such as mutation type, cancer risk, age of diagnosis and cancer type in this patient cohort. Of the 29 MSH6 mutation positive families, 16 fulfilled the Amsterdam II criteria and 1 fulfilled the Bethesda criteria, while 6 did not fulfil the guidelines for either (5 cases had loss of staining of MSH6, while 1 was MSI-High) and in 5 families the status was unknown (no pedigree/uninformative pedigree). Of the 6 PMS2 mutation positive families, 4 fulfilled the Amsterdam II criteria, while 2 families did not due to lack of family history of cancer or uninformative pedigree.

The diagnosis of the cancers in the mutation positive participants was confirmed in histopathological reports, while information of cancers in family members with unknown mutation status is collected from the family pedigrees.

Cumulative lifetime risk for MSH6 mutation carriers was calculated using Kaplan Meier survival analysis, and was determined on the basis of CRC being the 1st primary tumour against cancer free individuals and endometrial cancer being the 1st primary tumour against cancer free females. The observation time for the different cases was from birth until first cancer diagnosis or last follow-up appointment.

Results

MSH6 families

We identified 26 different MSH6 mutations in the 29 probands; a list of the mutations is shown in Table 1. Eleven of the identified MSH6 mutations have been reported before [16–23] and fifteen MSH6 mutations are novel mutations (six of these have been posted on the LOVD database and the remaining nine will be submitted). All mutations are considered causative and predictive testing has been offered to family members. Table 1 also lists available immunohistochemistry (IHC) and microsatellite instability (MSI) results from the participant's tumours. IHC results were available in 20 of the 29 families; the tumour of 16 probands showed lack of staining (-ve) for MSH6, 2 tumours were -ve MSH2 but positive (+ve) for MSH6, 1 tumour showed isolated loss of MSH6 while 1 was uninformative for MSH6 but +ve for MLH1, MSH2 and PMS2. MSI results were available from 6 probands, all displaying MSI-High (unstable), 4 of them belonging to the -ve MSH6 group.

Of the total 78 MSH6 mutation positive participants belonging to 29 families, only 21 participants (27%) had developed colorectal cancer (CRC). The average and median age of diagnosis of CRC was 48 years, ranging from 21 to 72 years. The median age of individuals who were cancer free at the time of sample collection was 44 years, ranging from 18-76, and the average age of this group was 45 years.

Cancer incidence in the MSH6 mutation positive families includes, in order of frequency (in how many families the cancer was observed): CRC in 23 families (79%); cancer of the endometrium in 17 families (59%); breast or prostate cancer in 7 families (24%); and ovarian cancer in 5 families (17%). Other extra colonic cancers, including lung, bladder, stomach, cervical, Hodgkin lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, pancreas, liver, throat, lymphoma, thyroid, leukaemia, kidney, gallbladder, brain, melanoma, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and pituitary tumour can be seen in four or less families. In six families, cancer of an unknown site was recorded (Table 2). Extra colonic cancers were diagnosed in 2 individuals (9.5%) who had developed CRC and in 14 individuals (25%) who had not developed CRC. Table 3 provides detailed information about the extracolonic cancers in these patients. A wide spectrum of malignancies was present in the 29 MSH6 families and individuals with two primary tumours were observed in 14 of the 29 families (48%), see Table 2 for details.

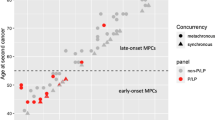

Lifetime/cumulative risk of developing colorectal and endometrial cancer are shown in Figure 1 and 2 respectively. The cumulative risk of CRC in both male and female mutation carriers at 70 years of age was 61.5% for MSH6 mutation carriers (Figure 1A), which is similar if divided by gender (Figure 1B). A difference can be seen between males and females at an earlier age with females only being at 21% risk at age 50 years, while males have a risk of ~34% at 50 years of age. The cumulative risk of endometrial cancer in woman at age 70 years was 65%.

Of the 53 female participants in this study, 10 had developed endometrial cancer and the average and median age of diagnosis was 59 and 57 years respectively, ranging from 50-74 years. In 6 of the 17 families where endometrial cancer had been recorded, there were one or more individuals who had both endometrial plus another primary tumour.

In 4 families pedigree information was not accessible and in 3 families the proband was cancer free (the proband is the first person tested from the family in our laboratory, the index person of the family might have been tested in another laboratory either national or international). For the 22 families where full family history was available, cancer was present in one of the probands' parents in 13 families.

PMS2 families

A list of the 4 identified PMS2 mutations can be seen in Table 4. Three of the identified PMS2 mutations have been reported before [24–26] and one PMS2 mutation is a novel mutation. All mutations are considered causative and predictive testing has been offered to family members. Table 4 also lists the type of cancer and age of diagnosis in the probands of these families.

The 7 PMS2 participants include 6 probands and 1 family member. Five probands had been diagnosed with CRC at age 38, 41, 47, 55 and 60 years, one of them (CRC at 55 years) was also diagnosed with renal cancer at age 50 years. One proband has not developed CRC but was diagnosed with cancer of the small intestine at 63 years of age; the family member of this proband is currently cancer free at age 39 years.

Cancer incidence in the PMS2 mutation positive families includes, in order of frequency (in how many families the cancer can be seen): CRC (6 families); lung, stomach and brain cancer (2 families); endometrial + breast cancer, and ovarian + breast cancer (1 family); breast, cervical, Merkel cell and small intestine cancer (1 family).

Discussion

The MSH6 participants included in this study are representative of all the HNPCC patients tested in New South Wales, Australia from 1997 to 2008, which we estimate is approximately half of the Australian HNPCC/Lynch syndrome families. The identified MSH6 mutations represent 10.3% of the pathogenic mutations identified in MMR genes in our Lynch syndrome families. This is in accordance with the expected frequencies of MSH6 mutations in already published material on Lynch syndrome [14, 20, 27, 28]. We report 15 novel MSH6 mutations and 1 novel PMS2 mutations in Lynch syndrome families not listed in the Mismatch Repair Genes Variant Database (Memorial University of Newfoundland), the InSIGHT database as a Lynch syndrome mutation or the Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD).

Families with MSH6 mutations have been reported to have a lower incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) and later age of disease onset than MLH1 and MSH2 families [20], while others suggest same high lifetime risk of CRC and later age of disease onset [15, 29]. In our Lynch syndrome cohort 27% had developed CRC, which is lower than expected [30]. This could be due to there being an over-representation of woman (68%) in the MSH6 participants, as woman have been reported to be at lower risk of CRC than men [30]. The median age of diagnosis of CRC was 48 years in the cohort studied, which is approximately 3-7 years younger than previously reported [20, 27, 31]. The median age for the rest of the cohort was 44 years, which is an indication of the likelihood of more people developing CRC at a later age and thereby increasing the median age of diagnosis of CRC. Exclusion of missense mutations in this study could also influence the low age of CRC observed, as cases were selected due to more severe alterations and the chance of developing CRC earlier is therefore higher. In this patient cohort the lifetime risk for CRC at age 70 years was ~61% independent of gender, which is somewhat different from the lifetime risk of MSH6 mutation carriers presented in a previous study were there was a clear difference between males and females at age 70 years [32]. The males in both studies had similar lifetime risk, but we fail to see the lower risk in woman. A meta-analysis of 5 different MSH6 mutation positive Lynch syndrome cohorts displayed a much lower lifetime risk of CRC at ~20% [33], which is an indication that our sample cohort might be too small to produce reliable lifetime risk figures.

The median age of endometrial cancer in this study was 59 years, supporting the much later onset of cancer in MSH6 mutation carriers [27]. Females in this patient cohort had a lifetime risk of endometrial cancer of 65% at 70 years of age, which is similar to previously reported risk figures for MSH6 mutation carriers [32] but again much higher than risk figures produced from a much larger study population [33]. Endometrial cancer was seen in 59% of the MSH6 families as the second most common malignancy observed. Extra colonic cancers were observed with a higher frequency in the participants who had not developed CRC compared to the participants who had developed CRC. These observations are in accordance with the cancer frequencies seen in the German Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer Consortium [20]. Cancer incidence in these families was as previously reported [30] with CRC being the most common, followed by endometrial cancer. Breast and prostate cancer were observed in 23% of the MSH6 families, while ovarian cancer was observed in 17% of the families. Both ovarian and prostate cancer were expected to be observed in Lynch syndrome families [34] but the inclusion of breast cancer in the cancer spectrum in Lynch syndrome is controversial [35–39]. The high incidence of breast cancer in these families may genuinely reflect an increased risk of breast cancer, or it may indicate the high incidence of breast cancer in the general population (1 in 9 woman in Australia [40]).

Previously, it has been reported that patients with pathogenic MSH6 mutations are less frequently affected by multiple tumours [20]. This does not seem to be the case in our families as one or more individuals who had been diagnosed with two primary malignancies occurred in 14 of the 29 MSH6 families.

Currently the general consensus is that MSH6 mutations in HNPCC are under-diagnosed [25, 35, 41]. This is thought to be due to MSH6 not being routinely tested in most laboratories and that the presence of MSH6 mutations is under-estimated due to a more atypical presentation of disease, making the patients less likely to fulfil diagnostic criteria. This is supported by a report of an unusual high incidence of MSH6 mutations (21%) in Amsterdam negative families [42]. In the current study, participants were selected based on the molecular diagnosis of Lynch syndrome, nevertheless 24% of our families did not fulfil the Amsterdam II criteria. There is no routine screening for MSH6 in our laboratory and it is only performed when there is loss of MSH6 expression in the tumour (IHC) or a family history indicating MSH6 mutation.

PMS2 mutations lead to an attenuated phenotype with weaker family history and an older age of onset [15]. Communicating cancer risk to PMS2 mutation carriers and deciding which surveillance protocol is adequate for the families is a difficult task for the genetic counsellor/geneticist. In this study, only 6 PMS2 families were included. While this is not enough families to be able to predict a PMS2 phenotype, it is important that the information is publicly available so that a PMS2 phenotype can be made in the future.

Lynch syndrome is a complex disease with variation in disease expression influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, as evidenced by differences in genotype-phenotype within and between families with the same mutations and by ethnicity and mutated MMR gene [43–45]. To date, no worldwide genotype-phenotype correlation has been detected. Our data provides additional information to add to the genotype-phenotype spectrum for both MSH6 and PMS2 mutations. As approximately half of the clinically diagnosed HNPCC population can be classified as having Lynch syndrome (germline mutation in MMR genes), there are most likely other genomic regions that are also responsible for the disease. Future next-generation sequencing are likely to provide us with some answers by locating new genomic regions of interest, as shown by identification of the EPCAM deletion [46], but until the methodology is widely available the candidate gene approach in individual Lynch syndrome cohorts will help us in understanding the genotype-phenotype mystery.

References

Lynch HT, Boland CR, Gong G, Shaw TG, Lynch PM, Fodde R, Lynch JF, de la Chapelle A: Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity in the Lynch syndrome: diagnostic, surveillance and management implications. Eur J Hum Genet 2006, 14: 390–402. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201584

Lawes DA, SenGupta SB, Boulos PB: Pathogenesis and clinical management of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2002, 89: 1357–1369. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02290.x

Lu K: Endometrial cancer in women with HNPCC. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005, 15: 400–401. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.t01-1-abst_4.x

Bronner CE, Baker SM, Morrison PT, Warren G, Smith LG, Lescoe MK, Kane M, Earabino C, Lipford J, Lindblom A: Mutation in the DNA mismatch repair gene homologue hMLH1 is associated with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Nature 1994, 368: 258–261. 10.1038/368258a0

Fishel R, Lescoe MK, Rao MR, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Garber J, Kane M, Kolodner R: The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell 1993, 75: 1027–1038. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3

Miyaki M, Konishi M, Tanaka K, Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Muraoka M, Yasuno M, Igari T, Koike M, Chiba M, Mori T: Germline mutation of MSH6 as the cause of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 1997, 17: 271–272. 10.1038/ng1197-271

Nicolaides NC, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, Wei YF, Carter KC, Ruben SM, Rosen CA, Haseltine WA, Fleischmann RD, Fraser CM, et al.: Mutations of two PMS homologues in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Nature 1994, 371: 75–80. 10.1038/371075a0

Jiricny J: The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006, 7: 335–346. 10.1038/nrm1907

Peltomaki P: Role of DNA mismatch repair defects in the pathogenesis of human cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003, 21: 1174–1179. 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.060

Silva FC, Valentin MD, Ferreira Fde O, Carraro DM, Rossi BM: Mismatch repair genes in Lynch syndrome: a review. Sao Paulo Med J 2009, 127: 46–51. 10.1590/S1516-31802009000100010

Chadwick RB, Meek JE, Prior TW, Peltomaki P, de La Chapelle A: Polymorphisms in a pseudogene highly homologous to PMS2. Hum Mutat 2000, 16: 530. 10.1002/1098-1004(200012)16:6<530::AID-HUMU15>3.0.CO;2-6

Hayward BE, De Vos M, Valleley EM, Charlton RS, Taylor GR, Sheridan E, Bonthron DT: Extensive gene conversion at the PMS2 DNA mismatch repair locus. Hum Mutat 2007, 28: 424–430. 10.1002/humu.20457

Niessen RC, Kleibeuker JH, Jager PO, Sijmons RH, Hofstra RM: Getting rid of the PMS2 pseudogenes: mission impossible? Hum Mutat 2007, 28: 414–415. 10.1002/humu.20447

Al-Sukhni W, Aronson M, Gallinger S: Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: familial adenomatous polyposis and lynch syndrome. Surg Clin North Am 2008, 88: 819–844. vii 10.1016/j.suc.2008.04.012

Boland CR, Koi M, Chang DK, Carethers JM: The biochemical basis of microsatellite instability and abnormal immunohistochemistry and clinical behavior in Lynch syndrome: from bench to bedside. Fam Cancer 2008, 7: 41–52. 10.1007/s10689-007-9145-9

Kolodner RD, Tytell JD, Schmeits JL, Kane MF, Gupta RD, Weger J, Wahlberg S, Fox EA, Peel D, Ziogas A, et al.: Germ-line msh6 mutations in colorectal cancer families. Cancer Res 1999, 59: 5068–5074.

Klift H, Wijnen J, Wagner A, Verkuilen P, Tops C, Otway R, Kohonen-Corish M, Vasen H, Oliani C, Barana D, et al.: Molecular characterization of the spectrum of genomic deletions in the mismatch repair genes MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, and PMS2 responsible for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2005, 44: 123–138. 10.1002/gcc.20219

Plaschke J, Ruschoff J, Schackert HK: Genomic rearrangements of hMSH6 contribute to the genetic predisposition in suspected hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. J Med Genet 2003, 40: 597–600. 10.1136/jmg.40.8.597

Goodfellow PJ, Buttin BM, Herzog TJ, Rader JS, Gibb RK, Swisher E, Look K, Walls KC, Fan MY, Mutch DG: Prevalence of defective DNA mismatch repair and MSH6 mutation in an unselected series of endometrial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100: 5908–5913. 10.1073/pnas.1030231100

Plaschke J, Engel C, Kruger S, Holinski-Feder E, Pagenstecher C, Mangold E, Moeslein G, Schulmann K, Gebert J, von Knebel Doeberitz M, et al.: Lower incidence of colorectal cancer and later age of disease onset in 27 families with pathogenic MSH6 germline mutations compared with families with MLH1 or MSH2 mutations: the German Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2004, 22: 4486–4494. 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.033

Wagner A, Barrows A, Wijnen JT, Klift H, Franken PF, Verkuijlen P, Nakagawa H, Geugien M, Jaghmohan-Changur S, Breukel C, et al.: Molecular analysis of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in the United States: high mutation detection rate among clinically selected families and characterization of an American founder genomic deletion of the MSH2 gene. Am J Hum Genet 2003, 72: 1088–1100. 10.1086/373963

Plaschke J, Kruger S, Pistorius S, Theissig F, Saeger HD, Schackert HK: Involvement of hMSH6 in the development of hereditary and sporadic colorectal cancer revealed by immunostaining is based on germline mutations, but rarely on somatic inactivation. Int J Cancer 2002, 97: 643–648. 10.1002/ijc.10097

Hampel H, Frankel W, Panescu J, Lockman J, Sotamaa K, Fix D, Comeras I, La Jeunesse J, Nakagawa H, Westman JA, et al.: Screening for Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) among endometrial cancer patients. Cancer Res 2006, 66: 7810–7817. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1114

Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, Hampel H, Green J, Potter JD, Lindblom A, Lagerstedt K, Thibodeau SN, Lindor NM, et al.: The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations. Gastroenterology 2008, 135: 419–428. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.026

Lagerstedt Robinson K, Liu T, Vandrovcova J, Halvarsson B, Clendenning M, Frebourg T, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Peltomaki P, et al.: Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) diagnostics. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007, 99: 291–299. 10.1093/jnci/djk051

Etzler J, Peyrl A, Zatkova A, Schildhaus HU, Ficek A, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Kratz CP, Attarbaschi A, Hainfellner JA, Yao S, et al.: RNA-based mutation analysis identifies an unusual MSH6 splicing defect and circumvents PMS2 pseudogene interference. Hum Mutat 2008, 29: 299–305. 10.1002/humu.20657

Zhao YS, Hu FL, Wang F, Han B, Li DD, Li XW, Zhu S: Meta-analysis of MSH6 gene mutation frequency in colorectal and endometrial cancers. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2009, 72: 690–697. 10.1080/15287390902841003

Devlin LA, Graham CA, Price JH, Morrison PJ: Germline MSH6 mutations are more prevalent in endometrial cancer patient cohorts than hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer cohorts. Ulster Med J 2008, 77: 25–30.

Kastrinos F, Syngal S: Recently identified colon cancer predispositions: MYH and MSH6 mutations. Semin Oncol 2007, 34: 418–424. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.07.005

Alarcon F, Lasset C, Carayol J, Bonadona V, Perdry H, Desseigne F, Wang Q, Bonaiti-Pellie C: Estimating cancer risk in HNPCC by the GRL method. Eur J Hum Genet 2007, 15: 831–836. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201843

Wagner A, Hendriks Y, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, de Leeuw WJ, Morreau H, Hofstra R, Tops C, Bik E, Brocker-Vriends AH, Meer C, et al.: Atypical HNPCC owing to MSH6 germline mutations: analysis of a large Dutch pedigree. J Med Genet 2001, 38: 318–322. 10.1136/jmg.38.5.318

Ramsoekh D, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Dooijes D, Tops CM, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ: Cancer risk in MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 mutation carriers; different risk profiles may influence clinical management. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2009, 7: 17. 10.1186/1897-4287-7-17

Baglietto L, Lindor NM, Dowty JG, White DM, Wagner A, Gomez Garcia EB, Vriends AH, Cartwright NR, Barnetson RA, Farrington SM, et al.: Risks of Lynch syndrome cancers for MSH6 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 102: 193–201.

Jarvinen HJ, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Aktan-Collan K, Peltomaki P, Aaltonen LA, Mecklin JP: Ten years after mutation testing for Lynch syndrome: cancer incidence and outcome in mutation-positive and mutation-negative family members. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27: 4793–4797. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7784

Goldberg Y, Porat RM, Kedar I, Shochat C, Galinsky D, Hamburger T, Hubert A, Strul H, Kariiv R, Ben-Avi L, et al.: An Ashkenazi founder mutation in the MSH6 gene leading to HNPCC. Fam Cancer 2009, in press.

Scott RJ, McPhillips M, Meldrum CJ, Fitzgerald PE, Adams K, Spigelman AD, du Sart D, Tucker K, Kirk J: Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in 95 families: differences and similarities between mutation-positive and mutation-negative kindreds. Am J Hum Genet 2001, 68: 118–127. 10.1086/316942

Muller A, Edmonston TB, Corao DA, Rose DG, Palazzo JP, Becker H, Fry RD, Rueschoff J, Fishel R: Exclusion of breast cancer as an integral tumor of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2002, 62: 1014–1019.

Oliveira Ferreira F, Napoli Ferreira CC, Rossi BM, Toshihiko Nakagawa W, Aguilar S, Monteiro Santos EM Jr, Vierira Costa ML, Lopes A: Frequency of extra-colonic tumors in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and familial colorectal cancer (FCC) Brazilian families: An analysis by a Brazilian Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Institutional Registry. Fam Cancer 2004, 3: 41–47. 10.1023/B:FAME.0000026810.99776.e9

Jensen UB, Sunde L, Timshel S, Halvarsson B, Nissen A, Bernstein I, Nilbert M: Mismatch repair defective breast cancer in the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010,120(3):777–82. 10.1007/s10549-009-0449-3

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF HEALTH AND WELFARE CANCER AUSTRALIA & AUSTRALASIAN ASSOCIATION OF CANCER REGISTRIES: Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: cancers diagnosed from 1982 to 2004. 2008.

Roncari B, Pedroni M, Maffei S, Di Gregorio C, Ponti G, Scarselli A, Losi L, Benatti P, Roncucci L, De Gaetani C, et al.: Frequency of constitutional MSH6 mutations in a consecutive series of families with clinical suspicion of HNPCC. Clin Genet 2007, 72: 230–237. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00856.x

Ramsoekh D, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Dinjens WN, Steyerberg EW, Halley DJ, Kuipers EJ, Dooijes D: A high incidence of MSH6 mutations in Amsterdam criteria II-negative families tested in a diagnostic setting. Gut 2008, 57: 1539–1544. 10.1136/gut.2008.156695

Jones JS, Chi X, Gu X, Lynch PM, Amos CI, Frazier ML: p53 polymorphism and age of onset of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in a Caucasian population. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10: 5845–5849. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0590

Talseth BA, Meldrum C, Suchy J, Kurzawski G, Lubinski J, Scott RJ: Age of diagnosis of colorectal cancer in HNPCC patients is more complex than that predicted by R72P polymorphism in TP53. Int J Cancer 2006, 118: 2479–2484. 10.1002/ijc.21661

Talseth BA, Meldrum C, Suchy J, Kurzawski G, Lubinski J, Scott RJ: Aurora-A and Cyclin D1 polymorphism and the age of onset of colorectal cancer in Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer. Int J Cancer 2008, 122: 1273–1277. 10.1002/ijc.23177

Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP, Chan TL, Goossens M, Hebeda KM, Voorendt M, Lee TY, Bodmer D, Hoenselaar E, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, et al.: Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3' exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet 2009, 41: 112–117. 10.1038/ng.283

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Hunter Medical Research Institute and Gladys M Brawn Memorial Fund through the University of Newcastle.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BTP: Study design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; statistical analysis. MM, CG and AS: Acquisition of data. RJS: Study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Talseth-Palmer, B.A., McPhillips, M., Groombridge, C. et al. MSH6 and PMS2 mutation positive Australian Lynch syndrome families: novel mutations, cancer risk and age of diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 8, 5 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-8-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-8-5