Abstract

Background

Germline mutations of the CHEK2 gene have been reported to be associated with breast cancer. In this study, we analyzed the association of CHEK2 mutations with the risk of development of breast cancer in women of North-Central Poland.

Methods

420 women with breast cancer and 435 controls were tested for three protein truncating (IVS2 + 1G > A, 1100delC, del5395) and one missense (I157T) CHEK2 mutation. IVS2 + 1G > A and I157T mutations were identified by RFLP-PCR, 1100delC variant was analyzed using an ASO-PCR and del5395 mutation by multiplex-PCR. The statistical tests: the odds ratio (OR) and Fisher’s exact test were used.

Results

In 33 out of 420 (7.9%) women consecutively diagnosed with breast cancer, we detected one of four analyzed CHEK2 mutations: I157T, 1100delC, IVS2 + 1G > A or del5395. Together they were not associated with the increased risk of breast cancer (North-Central control group: OR = 1.6, p = 0.124; the general Polish population: OR = 1.4, p = 0.109). This association was only seen for IVS2 + 1G > A mutation (OR = 3.0; p = 0.039). One of the three truncating CHEK2 mutations (IVS2 + 1G > A, 1100delC, del5395) was present in 9 of 420 women diagnosed with breast cancer (2.1%) and in 4 of 121 women (3.3%) with a history of breast cancer in a first- and/or second- degree relatives. Together they were associated with the increased risk of disease in these groups, compared to the general Polish population (OR = 2.1, p = 0.053 and OR = 3.2; p = 0.044, respectively). I157T mutation was detected in 25 of 420 women diagnosed with breast cancer (6.0%) and in 8 of 121 women (6.6%) with a history of breast cancer in first- and/or second- degree relatives. The prevalance of I157T mutation was 4.1% (18/435) in North-Central control group and 4.8% (265/5.496) in the general Polish population. However it was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.

Conclusion

Obtained results suggest that CHEK2 mutations could potentially contribute to the susceptibility to breast cancer. The germline mutations of CHEK2, especially the truncating ones confer low-penetrance breast cancer predisposition that contribute significantly to familial clustering of breast cancer at the population level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genetic basis of breast cancer (BC) is very complex and it is suggested that many various genes, especially tumor suppressors could play role in disease development [1].

The CHEK2 tumor suppressor gene belongs to the group of genes, which by regulating cell division protect the cells against too rapid, uncontrolled growth. In response to DNA damage Checkpoint kinase 2 (CHEK2) is activated on ATM-dependent pathway and then phosphorylates several substrates, such as p53, BRCA1 protein, CDC25A and CDC25C, involved in the cell cycle checkpoint control, through coordination of DNA repair, cell cycle progression and apoptosis [2].

Constitutional mutations of CHEK2 predispose to many types of common cancers, e.g. breast cancer [3–5]. In the general Polish population the most common CHEK2 mutations are I157T missense mutation and three premature protein-truncating mutations: IVS2 + 1G > A, del5395 and 1100delC, which prevalance is 4.8%, 0.4%, 0.4% and 0.2%, respectively [6].

In this report we present the results of research on association between congenital CHEK2 mutations and a risk of BC in women originating from the North-Central Poland, as well as the relation of these mutations to familial history of BC.

Materials and methods

Patients

420 women from the North-Central Poland (Kujawy-Pomerania voivodeship) with consecutively diagnosed BC, treated in 2007-2010 at the Oncology Center in Bydgoszcz, were included in the investigation, regardless of histopatological type and family history of the BC. The median age at BC diagnosis in the whole group was 46 years (range 26-73). One woman was diagnosed with bilateral BC – two primary cancers within two years (age 41 and 42).

In families of women with congenital CHEK2 mutations, molecular tests were performed. 61% (255/420) of women originated from families with at least one cancer in a close relative, the most frequently cancer of breast, ovary, lung, colon and prostate. 29% (121/420) of women originated from families with history of BC in first- and/or second- degree relatives. 5 out of 33 invited families (a total of 17 persons) agreed to be tested.

The first control group consisted of 435 healthy women from the North-Central region of Poland. The data on the general Polish population published by Cybulski et al. (2006) were used as the second control group (by courtesy of the Author) [6].

Informed consent was obtained from all patients and healthy persons. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Collegium Medicum, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Bydgoszcz, Poland.

Molecular analysis

The CHEK2 mutations analysis was performed in all 420 patients and 17 members of their families, as well as in all women from the first control group.

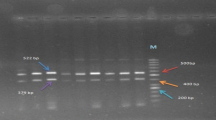

The mutations were investigated in DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes, extracted by standard salting-out method. I157T and IVS2 + 1G > A were examined by RFLP-PCR, 1100delC by ASO-PCR, and del5395 by multiplex-PCR with two primer pairs flanking breakpoint sites in introns 8 and 10 [3, 6].

Statistical analysis included the comparison of the frequency of variant alleles in studied and control groups. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated from two-by-two tables, and statistical significance of differences between tested and control groups was estimated using the Fisher’s exact test.

Results and discussion

At least one of CHEK 2 mutations was found in 33 out of 420 women diagnosed with BC (7.9%). This frequency was higher than in both control groups, however differences were not statistically significant (first control group: 5.1%, p = 0.124; second control group: 5.8%, p = 0.109) (Table 1). The observed lack of statistically significant correlation between carrying of a congenital CHEK2 mutation and the risk of BC in the patients from North-Central Poland may be caused by too small study groups.

The I157T, 1100delC and del5395 mutations separately were disclosed with 6.0%, 0.5% and 0.5% frequency, respectively, but none of these frequencies was statistically significantly different from the frequency in both control groups (first control group: 4.1%, 0.2%, 0.2%, respectively; second control group: 4.8%, 0.2%, 0.4%, respectively). However, the prevalence of IVS2 + 1G > A mutation was three-fold higher in relation to the general Polish population and the presence of this mutation turned out to be associated with an increased risk of BC (1.2% vs. 0.4%; OR = 3.0; p = 0.039) (Table 1).

Reports of other authors show that the frequency of CHEK2 mutations among women with diagnosed BC is different in various regions of Poland. Among BC women from throughout Poland and the South-Western Poland, these mutations were detected with higher frequency than in our investigations: 8.6% (385/4.454) and 9.9% (28/284), respectively [7, 8].

The increased risk of BC associated with three CHEK2 mutations IVS2 + 1G > A (1.1% vs. 0.48%; OR = 2.3, p = 0.04), 1100delC (0.5% vs. 0.25; OR = 2.0, p = 0.3) and I157T (6.7 vs. 4.8%; OR = 1.4, p = 0.02) was showed in 2004 by Cybulski et al. in BC women from the North-Western Poland and with four CHEK2 mutations: IVS2 + 1G > A (1.0% vs. 0.4%; OR = 2.4, p = 0.0008), 1100delC (0.4% vs. 0.2%; OR = 2.1, p = 0.07), I157T (6.5% vs. 4.8%; OR = 1.4, p = 0.0004), del5395 (0.9% vs. 0.4%; OR = 2.0, p = 0.009) in 2007 by the same authors in a large group of BC women from throughout the country [3, 7].

On the contrary, Myszka et al. (2011) did not show any relationship between the four investigated CHEK2 mutations and the risk of BC among BC women from the South-Western Poland [8]. Such correlation was not found either by Kwiatkowska et al. (2006), who investigated only the 1100delC mutation in women with BC originating from East-Central, West-Central and South-Eastern Poland [9].

However, Han et al. (2013) in the meta-analysis of the risk of breast cancer associated with CHEK2 I157T mutation in 15.985 patients from four countries (Bogdanova et al. 2005 [10]; Cybulski et al. 2004, 2009 [3, 11]; Domagała et al. 2012 [12]; Dufault et al. 2004 [13]; Irmejs et al. 2006 [14]; Kleibl et al. 2008 [15]; Serrano – Fernandez et al. 2009 [16]) found a strong correlation between carrying of CHEK2 I157T mutation and the risk of BC (OR = 1.58; p < 0.00001) [17].

In our study group any truncating CHEK2 mutation occurred with two-fold higher frequency than in general Polish population and we have also found their association with the increased risk of BC (2.1% vs. 1.1%; OR = 2.1, p = 0.053) (Table 1). Cybulski et al. also observed a strong association of truncating mutations with elevated risk of BC in women from throughout the country (OR = 2.2; p = 0.0001) [7].

We also investigated the association between a positive familial history of BC in first- and/or second-degree relatives and the risk of developing BC. In women from these families we detected three-fold higher frequency of truncating CHEK2 mutations together than in the general Polish population, and their association with the increased risk of BC (3.3% vs. 1.1%; OR = 3.2, p = 0.044). However, with regard to our control group, differences were at the limit of statistical significance (3.3% vs. 0.9%; OR = 3.7, p = 0.072), only. Among patients with truncating CHEK2 mutations the risk of BC in the group of women from families with BC aggregation was two-fold higher than among women with no family history of BC (first control group: OR = 3.7 vs. OR = 1.8, second control group: OR = 3.2 vs. OR = 1.6) (Table 1).

In women from families with BC aggregation, 1100delC mutation frequency was eight and a half-fold higher in relation to the general Polish population and the presence of this individual mutation turned out to be associated with an increased risk of BC (1.7% vs. 0.2%; OR = 7.7; p = 0.035) (Table 1).

Cybulski et al. also showed a higher relative risk of BC among women with family history of BC, carriers of one of the three truncating mutations, from throughout the Poland compared to women with no family history of BC: 4.1%, OR = 5.0 (95% CI, 3.3 to 7.6) versus 2.8%, OR = 3.3 (95% CI, 2.3 to 4.7) [18].

The results of family investigations indicate a strong, statistically significant association of the truncating mutations with BC development, which suggests that mutations in CHEK2 gene are associated with BC risk, especially in women originating from families with BC aggregation.

Our results are in favor of the results of Cybulski, and in contradiction with the results of Myszka and Kwiatkowska [3, 7–9, 18].

Our research, carried out in 5 families, confirmed hereditary character of all detected CHEK2 mutations (Figure 1). In family A, I157T mutation was detected in two sisters: one with BC (age 51), and the second healthy (age at the time of examination 46). In family B, woman with BC at age 47 and her two healthy brothers (age 61 and 53), as well as her two healthy daughters (age 26 and 22), were carriers of I157T. Vertical transmission of I157T and IVS2 + 1G > A mutations was also observed in family C. I157T was detected in healthy mother (age 75) and two her daughters: one healthy (age 50), one with BC (age 48). BC-affected daughter inherited also second mutation, IVS2 + 1G > A, through paternal line. The father, carrier of IVS2 + 1G > A, was diagnosed with prostate cancer (age at diagnosis unknown). Family D was burdened with the IVS2 + 1G > A mutation, which was disclosed in mother (BC at age 57) and in her two healthy daughters (age 38 and 25). 1100delC was found in family E, in three sisters, two of which were diagnosed with BC (age 51 and 43).

Pedigrees of families A-E, with CHEK2 mutations. Black symbols - persons affected with cancer; white symbols with a black dot inside - healthy mutation carriers. Age of cancer or age of CHEK2 mutation diagnosis in healthy persons is given in brackets. Br - breast cancer; Lu - lung cancer; Li - liver cancer; Pr - prostate cancer; Co - colon cancer. Arrows indicate probands. I157T, IVS2 + 1G > A or 1100delC - mutation carriers; N - analyzed persons who are not carriers of the mutation; n.t. - not tested.

In conclusion, we found a strong association between CHEK2 truncating mutations prevalence and breast cancer family history. We conclude that CHEK2 mutations are rare in BC, but our results suggest a tumor suppressor function of CHEK2 gene in a small proportion of breast cancers. Furthermore, our results suggest that the CHEK2 mutations are low-penetrance alleles with respect to BC. However, a variety of interactions between the mutated CHEK2 with other genes can be related to the development of BC. The presence of CHEK2 mutations in BC highlights the importance of the integrity of the DNA damage signals pathway in BC development. Although the mechanisms by which CHEK2 mutations contribute to the development of BC remain unknown, future studies may confirm the observations shown in the present report.

Abbreviations

- ASO:

-

Allele-specific oligonucleotide

- ATM:

-

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- Br:

-

Breast cancer

- CDC25A:

-

Cell division cycle 25 homolog A

- CDC25C:

-

Cell division cycle 25 homolog C

- CHEK2:

-

Cell-cycle checkpoint kinase 2

- Co:

-

Colon cancer

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- Li:

-

Liver cancer

- Lu:

-

Lung cancer

- N:

-

Analyzed persons who are not carriers of the mutation

- n.t:

-

Not tested

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- Pr:

-

Prostate cancer

- RFLP:

-

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

- p53:

-

Tumor protein p53.

References

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer: Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet 2001, 358: 1389–1399.

Ahn J, Urist M, Prives C: The Chk2 protein kinase. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004, 3: 1039–1047. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.033

Cybulski C, Górski B, Huzarski T, Masojć B, Mierzejewski M, Debniak T, Teodorczyk U, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Matyjasik J, Złowocka E, Lenner M, Grabowska E, Nej K, Castaneda J, Mędrek K, Szymańska A, Szymańska J, Kurzawski G, Suchy J, Oszurek O, Witek A, Narod SA, Lubiński J: CHEK2 is a multiorgan cancer susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet 2004, 75: 1131–1135. 10.1086/426403

Dong X, Wang L, Taniguchi K, Wang X, Cunningham JM, McDonnell SK, Qian C, Marks AF, Slager SL, Peterson BJ, Smith DI, Cheville JC, Blute ML, Jacobsen SJ, Schid DJ, Tindall DJ, Thibodeau SN, Liu W: Mutations in CHEK2 associated with prostate cancer risk. Am J Hum Genet 2003, 72: 270–280. 10.1086/346094

Lalloo F, Evans DG: Familial breast cancer. Clin Genet 2012, 82: 105–114. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01859.x

Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Górski B, Dębniak T, Masojć B, Jakubowska A, Gliniewicz B, Sikorski A, Stawicka M, Godlewski D, Kwias Z, Antczak A, Krajka K, Lauer W, Sosnowski M, Sikorska-Radek P, Bar K, Klijer R, Zdrojowy R, Małkiewicz B, Borkowski A, Borkowski T, Szwiec M, Narod SA, Lubiński J: A large germline deletion in the Chek2 kinase gene is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer. J Med Genet 2006, 43: 863–866. 10.1136/jmg.2006.044974

Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Górski B, Dębniak T, Masojć B, Jakubowska A, van de Watering T, Narod SA, Lubiński J: A deletion in CHEK2 of 5,395 bp predisposes to breast cancer in Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007, 102: 119–122. 10.1007/s10549-006-9320-y

Myszka A, Karpiński P, Ślęzak R, Czemarmazowicz H, Stembalska A, Gil J, Laczmańska I, Bednarczyk D, Szmida E, Sąsiadek MM: Irrelevance of CHEK2 variants to diagnosis of breast/ovarian cancer predisposition in Polish cohort. J Appl Genet 2011, 52: 185–191. 10.1007/s13353-010-0013-1

Kwiatkowska E, Skasko E, Niwinska A, Wojciechowska-Lacka A, Rachtan J, Molong L, Nowakowska D, Konopka B, Janiec-Jankowska A, Paszko Z, Steffen J: Low frequency of the CHEK2 1100delC mutation among breast cancer probands from three regions of Poland. Neoplasma 2006, 53: 305–308.

Bogdanova N, Enssen-Dubrowinskaja N, Feshchenko S, Lazjuk GI, Rogov YI, Dammann O, Bremer M, Karstens JH, Sohn C, Dork T: Association of two mutations in the CHEK2 gene with breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2005, 116: 263–266. 10.1002/ijc.21022

Cybulski C, Górski B, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Dębniak T, Wokołorczyk D, Jakubowska A, Serrano-Fernandez P, Dork T, Narod SA, Lubiński J: Effect of CHEK2 missense variant I157T on the risk of breast cancer in carriers of other CHEK2 or BRCA1 mutations. J Med Genet 2009, 46: 132–135.

Domagała P, Wokołorczyk D, Cybulski C, Huzarski T, Lubiński J, Domagała W: Different CHEK2 germline mutations are associated with distinct immunophenotypic molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012, 132: 937–945. 10.1007/s10549-011-1635-7

Dufault MR, Betz B, Wappenschmidt B, Hofmann W, Bandick K, Golla A, Pietschmann A, Nestle-Krämling C, Rhiem K, Hüttner C, von Lindern C, Dall P, Kiechle M, Untch M, Jonat W, Meindl A, Scherneck S, Niederacher D, Schmutzler RK, Arnold N: Limited relevance of the CHEK2 gene in hereditary breast cancer. Int J Cancer 2004, 110: 320–325. 10.1002/ijc.20073

Irmejs A, Miklasevics E, Boroschenko V, Gardovskis A, Vanags A, Melbarde-Gorkusa I, Bitina M, Suchy J, Gardovskis J: Pilot study on low penetrance breast and colorectal cancer predisposition markers in Latvia. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2006, 4: 48–51. 10.1186/1897-4287-4-1-48

Kleibl Z, Havranek O, Novotny J, Kleiblova P, Soucek P, Pohlreich P: Analysis of CHEK2 FHA domain in Czech patients with sporadic breast cancer revealed distinct rare genetic alterations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008, 112: 159–164. 10.1007/s10549-007-9838-7

Serrano-Fernandez P, Debniak T, Górski B, Bogdanova N, Dok T, Cybulski C, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Wokołorczyk D, Narod SA, Lubiński J: Synergistic interaction of variants in CHEK2 and BRCA2 on breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009, 117: 161–165. 10.1007/s10549-008-0249-1

Han FF, Guo CL, Liu LH: The effect of CHEK2 variant I157T on cancer susceptibility: evidence from a meta-analysis. DNA Cell Biol. 2013, 32: 329–335. 10.1089/dna.2013.1970

Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Jakubowska A, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Masojć B, Dębniak T, Górski B, Blecharz P, Narod SA, Lubiński J: Risk of breast cancer in women with a CHEK2 mutation with and without a family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29: 3747–3752. 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0778

Acknowledgement

The work was partially supported by the fund of the Collegium Medicum Nicolaus Copernicus University, Bydgoszcz, Poland, and partially by the grant of Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education: PBZ-MNiSW-05/I/2007/02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AB carried out the molecular genetic studies, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the manuscript. HJ conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. AJ-C, MH and MP-D carried out the molecular genetic studies. RL and MP enrolled the patients into the study group. OH designed the study, participated in writing, critically revised the manuscript and approved its final version. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bąk, A., Janiszewska, H., Junkiert-Czarnecka, A. et al. A risk of breast cancer in women - carriers of constitutional CHEK2 gene mutations, originating from the North - Central Poland. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 12, 10 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-12-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-12-10