Abstract

In 21st-century public health, rapid urbanization and mental health disorders are a growing global concern. The relationship between diet, brain function and the risk of mental disorders has been the subject of intense research in recent years. In this review, we examine some of the potential socioeconomic and environmental challenges detracting from the traditional dietary patterns that might otherwise support positive mental health. In the context of urban expansion, climate change, cultural and technological changes and the global industrialization and ultraprocessing of food, findings related to nutrition and mental health are connected to some of the most pressing issues of our time. The research is also of relevance to matters of biophysiological anthropology. We explore some aspects of a potential evolutionary mismatch between our ancestral past (Paleolithic, Neolithic) and the contemporary nutritional environment. Changes related to dietary acid load, advanced glycation end products and microbiota (via dietary choices and cooking practices) may be of relevance to depression, anxiety and other mental disorders. In particular, the results of emerging studies demonstrate the importance of prenatal and early childhood dietary practices within the developmental origins of health and disease concept. There is still much work to be done before these population studies and their mirrored advances in bench research can provide translation to clinical medicine and public health policy. However, the clear message is that in the midst of a looming global epidemic, we ignore nutrition at our peril.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urbanization, commonly defined as the change in size, density and heterogeneity of cities, is a rapidly occurring global phenomenon. Projections suggest that within the next several decades, urbanization will continue in both developed and developing nations, such that by 2050 86% of the population of developed nations and 64% of developing nations will be urban residents. More immediately, by 2030, it is estimated that there will be an additional 1.35 billion people living in world cities [1, 2].

Urbanicity, a term that more specifically refers to the presence of conditions that are particular to urban vs nonurban areas, is ultimately defined as the impact of living in urban areas at a given time [3]. We acknowledge that urbanization and urbanicity can bring many potential benefits, including, but not limited to, those involving commerce, trade, education, communications and the efficient delivery of government and health-care services; however, the problems associated with rapid urbanization are many. In particular, urbanization is increasingly linked to changes in behavior that contribute to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) or so-called diseases of civilization. For example, urbanization has been associated with diminished levels of physical activity, compromised sleep and unhealthy dietary choices [3–8].

A related issue is the globalization of the food industry, reflected in substantial changes in efficiencies of production, marketing, transport, advertising and sale of food; this has prompted profound shifts in the composition of diets globally and has been one of the major drivers of changes in the distribution and burden of the NCDs over the second half of the 20th century [9, 10]. These changes may particularly affect those residing in deprived urban and suburban areas where there is a far higher density of retail venues that facilitate the consumption of unhealthy food commodities [11].

Among the NCDs, mental disorders—major depression and anxiety in particular—have been described as an impending global epidemic. Although less is known concerning the prevalence of these disorders in developing nations than elsewhere [12, 13], all data indicate that the burden of disease attributable to mental disorders will continue to rise globally over the coming decades [14]. Living in an urban environment [15–17], as well as global shifts associated with urbanicity [18–21], the food supply and food industry [22], climate change [23], food insecurity [24, 25], overnutrition and underactivity [26] and an overall transition from traditional lifestyles [27–29] have each been linked to increases in depression and other mental disorders. It is understood that depression and other mental disorders are not exclusive to urban areas; however, higher rates in urban areas have been reported with a degree of consistency [30, 31]. Moreover, looking specifically at neighborhood disadvantage, the adjusted odds of experiencing an emotional disorder are 59% higher in urban youth vs those in rural areas [32].

Regardless of the urban–rural divide, within developed nations, up to one-third of all visits to primary care clinicians involve patients with emotional disorders, most notably anxiety and/or depressive conditions [33]. In both developed nations and those in the midst of an epidemiological transition, depression is rapidly rising within the burden of disease rankings [34–36]. Moreover, depression is already part of an epidemic of comorbidity and will likely become even more so. Specifically, obesity, type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases strongly associated with lifestyle behaviors are highly comorbid with depression [37, 38].

Because diagnosable depression and anxiety [39–41] (and their subclinical and subthreshold variants that may otherwise escape detection [42]) are also outcomes associated with, and drivers of, subsequent cardiovascular and other chronic disease states (that is, they are both upstream and downstream of “physical” illness), a multidisciplinary approach to prevention and treatment is necessary [43]. The results of studies involving adults with depression indicate that treatment outcomes from standard first-line antidepressant or psychotherapy interventions (for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy) are far from being universally adequate. Notwithstanding the debates concerning the placebo effect vs antidepressant efficacy [44, 45] and their potential adverse effects [46] (as well as publication biases concerning cognitive–behavioral therapy [47–49]), treatment resistance, relapse and nonresponse remain a reality [50, 51]. Moreover, even with optimal care and access to services, the results of modeling studies suggest that only a proportion of the burden of mental disorders can be averted, pointing to a clear need to focus on prevention to reduce the incidence of mental disorders [52]. From a research perspective, there is an urgent need to examine various environmental or lifestyle variables more thoroughly, including those wherein there are scientifically plausible mechanisms that can explain risk.

With this background in mind, we explore recent developments within an emerging discipline known as nutritional psychiatry. The relationship between dietary patterns and risk of mental health disorders has been the subject of intense research in recent years. There seems little doubt that dietary patterns and mental health, as well as other NCDs, are intertwined with socioeconomic circumstances [53]. We examine some of the potential socioeconomic and environmental challenges that detract from a dietary pattern or optimal nutrient intake that might otherwise support positive mental health.

As discussed below, in the context of urbanization, cultural and technological changes and the global industrialization and ultraprocessing of food, the findings related to nutrition and mental health are connected to some of the most pressing issues of our time. They are also of relevance to matters of biophysiological anthropology and a potential evolutionary mismatch between our ancestral past and the contemporary nutritional environment. At the outset, we acknowledge that much of our focus here is on depression. This is largely because depression has received the lion’s share of international research attention as it relates to some of the nutritional and environmental variables; however, it should be understood that these discussions are of relevance to diverse topics ranging from reductions in violent behavior [54] to overall positive mental outlook in those who are otherwise well-adjusted [55, 56].

Nutritional psychiatry research

Among the variables that might afford resiliency against mental disorders or, on the other hand, contribute to risk, diet has emerged as a strong candidate [57]. Viewed superficially, nutrition is a variable that needs little explanation in terms of its mechanistic potential. The brain operates at a very high metabolic rate, utilizing a substantial proportion of the body’s energy and nutrient intake. The very structure and function (intra- and intercellular communication) of the brain is dependent upon amino acids, fats, vitamins and minerals and trace elements. The antioxidant defense system operates with the support of nutrient cofactors and phytochemicals and is of particular relevance to psychiatry [58]. Similarly, the functioning of the immune system is of substantial importance to psychiatric disorders and profoundly influenced by diet and other lifestyle factors [59]. Neuronal development and repair mechanisms (neurotrophic factors) throughout life are also highly influenced by nutritional factors [60]. In short, a theoretical framework of biological mechanisms whereby nutrition could exert its influence along a continuum ranging from general mental well-being to neuropsychiatric disorders is highly plausible. However, despite its role as the foundation of physiological processes, nutrition as a factor in promoting positive mental health (or working against it) has traditionally suffered from scientific neglect and/or poorly designed studies that compromise interpretation.

Encouragingly, there are signposts indicating a major shift related to nutritional matters in mental health. Given the aforementioned background on the burden of mental disorders, this development is timely. A variety of epidemiological studies, including high-quality prospective studies, have linked adherence to healthful dietary patterns with lowered risk of anxiety and/or depression [61–67]. The results of these studies indicate that nutrition may provide a very meaningful layer of resiliency. The effect sizes suggest a clinically relevant value, not simply a minimal statistical significance. Healthy dietary patterns characterized by a high intake of vegetables, fruits, potatoes, soy products, mushrooms, seaweed and fish have recently been associated with a decreased risk of suicide [68]. Specific elements of the diet—green tea and coffee, for example—have also been linked to a decreased risk of depressive symptoms [69]. Moreover, nutrition is emerging as a critical factor within the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) construct. Early nutrition is now being linked, convincingly, to later mental health outcomes [70]. Moreover, at the other end of the lifespan, adherence to a Mediterranean diet results in better cognitive outcomes and a reduced risk for dementia [71, 72].

In support of these large population studies, at the opposite end of the research continuum, sophisticated bench studies are determining the pathways whereby individual elements of diet—polyphenols, for example—can influence brain function [73–75]. The area of dietary fats is yet another area of intense scrutiny, one where high-fat, obesogenic diets consumed during the pre- and perinatal period have been associated with long-term changes in neurotransmission, brain plasticity and behavior in offspring [76–78]. Moreover, beyond the detrimental effects of excessive fat per se, recent experimental evidence suggests that all fats, and even classes of fats (for example, various saturated fat sources), cannot be painted with the same brush in the context of brain health [79–82]. It is also worth noting that the results of numerous international studies have linked low blood cholesterol levels with suicide risk [83], a finding that might be related to low levels of the more specific high-density lipoprotein that is otherwise promoted through healthy dietary practices [84].

On the one hand, in between the epidemiological and experimental evidence, the results of a variety of clinical studies suggest the value of ω-3-rich oils in disorders including, but not limited to, bipolar depression [85], posttraumatic stress disorder [86], major depression [87] and the indicated prevention of psychosis [88]. On the other hand, given the brain’s continuous use of such a wide variety of nutrients for its structure and function, and the potential errors in metabolism that may be at play in mental disorders, the traditional focus on a single-nutrient resolution [89] may mask the potential value of multinutrient interventions [90]. Zinc provides a good example. The results of a number of preclinical and clinical studies have indicated that zinc supplementation may be helpful for people with major depression [91], and low dietary zinc has not only been correlated with depression [92], but has also been linked to abnormalities in the response to antidepressant medication [93]. However, zinc is well-established to play key roles in the metabolism of ω-3 and other essential fatty acids [94]. Indeed, there are complex ways in which ω-3 and zinc work together in the epigenetic control of human neuronal cells [95]. It is likely, therefore, that in the clinical setting, a combination of nutrients may provide better outcomes [96]. In the process of translational medicine, further examination of multinutrient bench and intervention studies will be necessary [97, 98].

For better or for worse, large percentages of adults in developed nations are consumers of dietary supplements [99], and this seems especially true of those with mental disorders. For example, two-thirds of all patients with mood disorders in one recent Canadian study were found to be supplement consumers, and 58% were taking supplements in combination with psychotropic medications [100]. Such findings only add to the urgency of evaluating the role and importance of nutritional variables, ranging from overall dietary patterns to the epigenetic controls exerted by isolated nutrients. Moreover, there is a clear need to explicate in detail the ways in which dietary supplements may interact with medications, particularly the widely prescribed classes of antidepressants and anxiolytics.

There is also an imperative to examine more closely the ways in which the nonnutritional elements of the modern diet may contribute to various brain-related disorders. Such research should include, but is certainly not limited to, the possible role of food-derived residual pesticides in brain health [101] and the ways in which synthetic food dyes, artificial sweeteners and flavor enhancers may influence behavior [102–104]. The results of preliminary randomized, placebo-controlled research suggest that short-term exposure to gluten can induce depressive symptoms in people with nonceliac gluten sensitivity [105].

Although it is commonly held that there is “no health without mental health” [106], the emerging evidence suggests that the opposite is also true: Good physical health and aerobic fitness are vitally important to mental health [107, 108]. We would argue that if a healthy diet influences mood, it might also increase the likelihood that an individual will remain physically active. This might be especially true in people with depression or obesity, in whom mood-related barriers diminish the desire perform physical activity or minimize its postexertion appeal [109–111]. A positive emotional state encourages future participation in physical activity [112, 113]. Supplementation of individual components of traditional diets, such as vitamin C, have been shown to reduce heart rate, perceived exertion and general fatigue postexercise in overweight adults [114]. Adoption of the Mediterranean diet for 10 days has been found to result in significantly increased vigor, alertness and contentment among participants vs controls [115]. Adherence to traditional diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, has been linked to objectively measured physical performance [116, 117]. More research is required to tease apart the ways in which nutrition can be used to tackle the motivational barriers to initiating and maintaining a routine of physical activity.

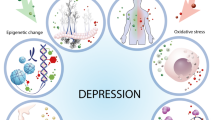

In people with mental disorders (and even acute diminished mental outlook), there appears to be involvement of chronic low-grade inflammation [118], oxidative stress [119], impaired metabolism [120], alterations to microbiota [121] and numerous other pathways that can be mediated by nutrition. In particular, there is currently much enthusiasm surrounding the potential of probiotics and prebiotics (or any agents capable of causing favorable shifts in the intestinal microbiota) as a means to promote positive mental health [122]. However, there has been little attention paid to the central role of diet as a variable working for or against the potential value, particularly over the long term, of these so-called psychobiotics [123, 124]. The same high-fat Westernized dietary factors that may negatively alter intestinal microbiota and promote intestinal permeability (provoking low-grade systemic inflammation via lipopolysaccharide endotoxin [121]) have also been shown to disrupt the critically important blood–brain barrier [125–127]. There may be untold consequences of diet-induced assaults to the integrity of both intestinal and the blood–brain barriers as they relate to mental health.

Clearly, there have been exciting advances in nutritional psychiatry research. The overall findings make it clear that nutrition matters in mental health. However, the degree to which nutrition matters remains unknown; the existing research, beyond validating nutrition as a variable of importance, has also served to generate a myriad of research questions that will require evidence-based answers. This in itself supports our call for broad collaboration to move this field of investigation forward and to explicate mechanistic pathways in order to identify targets for intervention. Many of the obstacles to learning how and the extent to which nutrition can work for or against positive mental health are related to the complex ways in which nutrition is intertwined with social, cultural and economic factors. In the next section, we address some of those complexities.

Environmental challenges, social determinants

The available evidence suggests that traditional dietary habits are beneficial for positive mental health and that unhealthy dietary choices are a related (but independent) detractor from a state of good mental health. Assuming for a moment that the evidence continues to grow more robust (an assumption generally supported by current meta-analysis results [66, 128]), the critical components of next-phase research will include further examination of the environmental factors that push toward (or pull away from) healthy, traditional dietary patterns. The environmental forces that facilitate a pull away from traditional diets appear to be extraordinarily strong.

Before examining some of the environmental factors that may work against nutrition for mental health, it is important to consider two contextual facts. First, mental health disparities within nations are commonplace; for example, depression does not occur randomly, and its rates, along with other mental disorders, are far higher in the disadvantaged social strata [129–131]. Second, the volumes of international research concerning obesity are likely of major relevance to the global mental health crisis. There seems little dispute that obesity can contribute to subsequent mental health problems. However, there are convincing prospective studies showing just the opposite—that depression and/or anxiety in children and adults predict subsequent weight gain over time [39, 132–137]. Therefore, scientific discussions concerning environmental factors related to obesity are highly relevant to the topic of mental health [138]. Also, much like depression, obesity is not randomly distributed within nations; it, too, is slanted toward neighborhood deprivation and lower socioeconomic strata (SES) [139].

Global urbanization, highlighted in the Introduction, is clearly linked to higher consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and beverages. The results of epidemiological and experimental research suggest that it is the highly palatable combination of sugar, fat and sodium that plays a key role in the attractiveness of such foods [140–142]. From an evolutionary perspective, the pleasure associated with energy-dense food consumption in the ancestral environment could motivate intake as a means of offsetting the scarcity of foods. Moreover, contemporary economic factors magnify the allure of inexpensive, widely available, energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods. Research indicates that higher costs are associated with nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables and quality protein sources such as fish and lean meat [143–145].

Animal experiments with the so-called cafeteria (Westernized) diet back up the contention that the availability and variety of palatable energy-dense foods drives long-term overconsumption of those foods, coincident with alterations to gene expression in the brain’s reward system [146, 147]. Indeed, experimental models of early-life stress show that the cafeteria diet can dampen the stress response, indicating that its consumption may be a form of self-medication [148]. This is supported by human research on the relationship between psychological distress and the increased consumption of so-called comfort foods [149–151]. Indeed, research shows that, at least in healthy adults, the direct infusion of fatty acids into the stomach (bypassing visual, gustatory and olfactory cues) can rapidly attenuate a laboratory-induced negative mood state [152].

Taken together, the physiological responses to the consumption of energy-dense comfort foods are likely to be behaviorally reinforced in people with mental health disorders. If we factor in economics and convenience in people who experience financial stress and physical fatigue, the likelihood of these foods’ being preferentially consumed increases. Moreover, the urban environment of people who live in low-SES neighborhoods, as it relates to food, is much different from that in affluent areas. Not only are fast-food outlets and convenience stores commonplace in disadvantaged neighborhoods [11, 153–155], but outdoor advertising of high-energy, low-nutrient foods and beverages is more prevalent there [156–158]. Not surprisingly, because there is little dispute that well-financed, targeted marketing is effective [159], brand name logo recognition of major fast-food outlets is high among children in low-SES neighborhoods [160].

Research also shows, on the one hand, that people in a lowered mood state are less likely to focus on the future health consequences of dietary decisions. Positive mood, on the other hand, increases the likelihood that an individual will not discount the future implications of what they are eating in the here and now [161]. This type of research, under the umbrella term of delayed (or temporal) discounting, is important in the context of the urban nutritional environment. Humans are prone to discount the value of future rewards and prioritize smaller but more immediate rewards. The strength of discounting, however, is associated with impulsivity, depression, obesity and unhealthy lifestyle habits [153, 162–165]. Minimal discounting of future considerations (that is, placing a high value on the future) is associated with a healthier diet and higher physical activity levels [166]. The overall cognitive load within an urban environment may magnify delayed discounting [167]. Subtle aspects of the urban environment, such as subconscious exposure to fast-food logos or even answering surveys in the general proximity of an urban fast-food outlet (vs full-service restaurant), increase impatience and encourage the discounting of future rewards for immediate gain. The immediate gain in this case might be the pleasure associated with low-nutrient, highly palatable foods and beverages. Moreover, individuals who reside in neighborhoods with high concentrations of fast-food outlets are more likely to prefer smaller immediate rewards over larger future gains [155].

Moving along this continuum, emerging research shows that food advertising as a driver of unhealthy food consumption is more pronounced when cognitive load is high (that is, distracting mental demands) and that those with lower SES backgrounds are more susceptible to the effects of advertising under cognitive load [168]. New research also confirms that excessive fast-food consumption is indeed attributable to the neighborhood food environment, with as much as 31% of the variance in excessive consumption attributable to living in urban areas with a moderate or high density of fast-food outlets [169]. However, fruit and vegetable consumption is markedly diminished in neighborhoods with a high clustering of fast-food outlets [170, 171]. Surrogate physiological markers of fruit and vegetable intake (for example, serum carotenoids) support the notion that adults who reside in deprived or lower SES neighborhoods are less likely to consume these foods or may displace them with unhealthy choices [172, 173].

Connected to the marketing forces influencing a pull away from traditional dietary habits is screen-based media consumption. Excess screen-based media consumption and so-called technostress have recently been linked to poor psychological health [174–182], and research shows that in neighborhoods where walkability is less than optimal, screen time is higher [183, 184]. Moreover, children who reside in urban environments [185] and deprived neighborhoods [186] have higher daily screen time than their rural or affluent counterparts. Higher screen time and depression could merely be a matter of association with less physical activity [187]; however, research shows that screen time (independently of physical activity) is significantly associated with the consumption of high-energy, low-nutrient foods and beverages [188]. Prospective research shows that baseline screen time predicts higher consumption of sugar-rich beverages when queried 20 to 24 months later [189, 190]. Similar results have been reported concerning baseline screen time and subsequent dietary habits in high school students and young adults: More screen time was found to predict consumption of fast-food, snacks and high-energy foods and beverages 5 years later [191]. The ways in which screen media can influence nutritional imbalances by encouraging high-energy, low-nutrient food consumption—via distraction of the activity itself and marketing of such foods during the activity [192–195]—is an area of research which requires expansion.

Evening screen media consumption, and even low levels of light at night (LAN), may suppress melatonin levels and compromise sleep [196]. Compromised sleep, too, has not only been linked to depression but also is associated with a prioritization of unhealthy foods choices [197, 198], and, at least in experimental models, LAN results in a more pronounced inflammatory response to high-fat foods [199]. Indeed, circadian rhythm disruption appears to be a distinct biological stressor that interacts with Westernized dietary patterns in the promotion of intestinal permeability and the loss of normal intestinal microbiota [200, 201].

Despite the research indicating that the consumption of energy-dense, high-fat, high-sugar and sodium-rich foods may be a highly palatable form of self-medication, the results of collection of dietary records and mood scores over a weekly period suggest that (in healthy university students) consumption of such foods increases negative mood 48 hours after consumption [202]. Additionally, food and beverage consumption is often a social activity. A greater understanding of the ways in which social isolation can minimize dietary diversity [203] or social support can facilitate healthy dietary patterns [204] is an essential area of research in nutritional psychiatry.

As a segue to our discussion regarding the evolutionary mismatch and nutritional anthropology, it is important to point out the cultural aspects of traditional dietary patterns as exemplified by the Mediterranean and Japanese models. It is not by chance that the Japanese and Mediterranean diets are each officially listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) on its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding and Register of Best Safeguarding Practices [205]. Both of these dietary patterns are steeped in tradition—nutritionally and otherwise. The listing by UNESCO specifically makes reference to the shared family and community experience in the consumption of these respective diets, including the ways in which dietary practices have been passed down from generation to generation. In other words, the cultural aspects of the diets are integral to adherence.

Cultural influences remain a driver of traditional dietary patterns; however, the Westernization of Japanese and Mediterranean diets appears to be corroding the culture of dietary tradition in both regions [206–208]. Lower rates of adherence to the Mediterranean diet have been reported to be common among urban youth in Italy and Greece compared to their rural counterparts [209, 210]. Lower amounts of screen time are associated with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Italian children [211]. The extent to which individual interest in traditional dietary patterns is associated with both social capital and psychological distress is a subject of ongoing research [212].

The relationships between healthy dietary habits and mental health are obviously complex. They weave their way through many aspects of modern technology and culture. The extent to which these nutritionally related environmental challenges ultimately contribute to the causation of mental disorders or present a barrier to effective treatment is a question in clear need of exploration. We hope that this will be the legacy of the field of nutritional psychiatry. In the meantime, it seems safe to say that the environmental challenges discussed above, those that might accelerate the adoption of Western dietary patterns, are colliding with an ancestral past that is still dictating human physiology [213].

Evolutionary mismatch?

Nutritional anthropology has taught us much concerning the makeup of ancestral dietary patterns. Undoubtedly, the ancestral diets were regionally varied, and it seems clear that there was no archetypal “Stone Age cuisine.” However, despite their differences, ancestral diets largely included a high intake of plant foods (rich in fiber and phytochemicals and facilitating a net base production), animal foods and a diverse range of commensal bacteria. Ancestral diets were also united by their absence of highly processed foods containing high sodium, added fats and refined sugar. In other words, the anthropological evidence concerning ancestral diets indicates that their regional and seasonal differences were minor compared to the ways in which they differ from the modern nutritional landscape [214, 215]. With this in mind, we can move toward discussions of evolutionary perspectives and epigenetic opportunities. After some background and historical framing, we next focus on three components of ancestral and traditional dietary practices: cooking techniques, dietary acid load and microbiota.

Evolutionary explanations for contemporary increases in psychopathologies include the mismatch theory. Broadly, this proposal suggests that there are gaps between the physiological and psychological requirements of individuals, as determined through millennia of adaptation to natural and social environments, and the ability of the modern environment to help fulfill those brain or mental health–related needs [29, 216]. The likelihood of mismatch is increased, according to theory, when culture and technology change more rapidly than human biological evolution [217]. Some of the lifestyle modifications associated with rapid technological and cultural changes—diminished physical activity, daily hassles and low-grade psychological stress, increased consumption of low-nutrient and energy-dense foods, loss of biodiversity in microbial contact—could chronically and unnecessarily stoke an immune defense system that is stuck in its ancestral past [218]. The ancestral immune system remains biologically well-adapted to preventing pathogen invasion, limiting acute infections, working with commensal microbes and assisting in programming the development of the nervous system [219]. However, its ability to perform these and other functions, as it has done for millennia, may now involve collateral damage in the form of allergies, asthma, autoimmune conditions and increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders [220–222].

The notion that modern dietary intake is at odds with our ancestral past, and that this disconnect has health-related consequences, is not new. In the early part of the 20th century, a small minority of medical writers were sounding alarms concerning the implications of a shift away from traditional diets. In 1922, the editors of the Medical Standard journal issued a stern warning concerning the increased consumption of the “output of the candy shop, soda fountain or pastry shop,” or, as they called it, “denatured, devitalized and demoralized foodstuffs.” More specifically, the editors’ argument was that such foods and beverages were at odds with optimal physiological functioning: “In other words, any kind of food is unfit to eat when its composition, through some artificial form of kitchen treatment, has become hostile to physiological life.… What is not for me is against me.… Never before in the world’s history of individual evolution were so many temptations put before him in the field of appetite and sensuous appeal as today” [223]. Also at this time, some experts were examining the dietary practices of people maintaining an isolated or indigenous existence [224], and others, such as noted nutritional scientist Frances Stern (1873–1947; later she would have a clinic at Tufts Medical Center (Boston, MA, USA) dedicated in her name), were assisting disadvantaged immigrants with ways in which to maintain their traditional dietary habits in an affordable way [225].

Stern, for her part, addressed the leaders of North American psychiatry at an annual conference in 1929, “hoping that the leaders there may guide the nutritionist to greater wisdom in the treatment of her patient.… In the field of dietotherapy, however, there is need of further light from psychiatry with regard to the interpretation of the mental life of patients, and the nutritionist is looking to the mental hygiene movement for research into the nature of the relationships between food and disturbances of the emotional life” [226]. Only today, the better part of a century later, has a response to Stern’s plea begun to take shape. From the perspective of nutritional anthropology, it was not until the 1980s that a scientific framework began to emerge, one in which shifts away from traditional dietary habits were at the core of the mismatch discussions and connections to chronic degenerative diseases [227].

Dietary patterns are more than simply reflections of macronutrients. In addition to the cultural aspects alluded to earlier, they involve methods of preparation. Experts in anthropology have noted that cooking techniques involving water—steaming and boiling—were widespread in our ancestral past. Indeed, although the precise dating of so-called Stone Age soups and stews remains unknown, they appear to be a minimum of 20,000 years old [228]. Some experts suggest that the use of steam to release necessary fat from animal bones may have been in practice 50,000 years ago or more [229, 230]. Suffice it to say that water-based cooking is an ancient practice. Those investigating the marked shift away from traditional dietary patterns in China and elsewhere have noted that the shifts toward processed foods and less potassium-rich foods are associated with changes in cooking technique. Specifically, there has been a decline in the consumption of foods prepared by steaming or boiling [4]. The traditional Japanese diet, one currently undergoing erosion, has included steamed and boiled foods since its early origins [231]. Indeed, the dashi (soup stock) is said to be the backbone of Japanese cuisine. Dashi made with flakes of dried bonito has been shown to improve mental outlook in randomized, controlled human trials [232] and to reduce anxiety-like behavior in experimental rodent studies [233].

One of the consequences of a shift away from water-based cooking to that of high heat in the absence of water (that is, baking, roasting, grilling, frying) is that it encourages the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Not to be confused with heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) produced by grilling meats (HCAs and PAHs experimentally linked to cancer), AGEs are highly oxidant compounds formed through the nonenzymatic reaction between reducing sugars and free amino acids. AGEs form in the body under normal metabolic circumstances; however, oxidative stress and inflammation are a well-known consequence of AGE levels rising beyond normal limits. The results of recent investigations have shown that the preformed AGEs in foods also add to the endogenous AGE burden. When considering the Westernized dietary pattern, with its reliance on foods thermally processed with high (dry) heat to enhance flavor, appearance and color, it should not be surprising that many of its foods are very high in AGEs [234]. The results of human studies have shown that a shift toward stewing, steaming, poaching and boiling of foods (lowering the AGE burden by approximately 50%) significantly reduces systemic inflammation and oxidative stress [235, 236]. Most of the research has been focused on type 2 diabetes and obesity, with improvements in insulin sensitivity noted in both populations after a switch to a low-AGE diet [237, 238]. Interestingly, people with depression and schizophrenia have low blood levels of soluble receptor for AGEs, a receptor tasked with binding and essentially halting some of the destructive consequences of AGEs [239, 240]. The emerging research related to AGEs forces us to look at not only dietary patterns but also the ways in which the foods within these patterns are prepared.

Another understudied aspect of the relevance of ancestral diets in contemporary mental health relates to the dietary acid load. Acid–base homeostasis is an example of a tightly controlled set of physiological mechanisms, checks and balances that are almost certainly a by-product of the Paleolithic nutritional environment [241]. The best available evidence suggests that the diets of our early East African ancestors were predominantly net base-producing [242]. The Westernized diet, with its heavy protein (amino acid) load, sodium intake and relative absence of fruits and vegetables (typically rich in buffering potassium, bicarbonate precursors, magnesium and calcium), has been linked to what has been described as a low-grade systemic metabolic acidosis in otherwise healthy adults [243]. Notwithstanding the pseudoscientific extrapolation of the low-grade acidosis proposal into so-called alkaline diets by lay writers, intriguing prospective research has shown that dietary acid load increases subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes [244]. Acid load has also been linked to cardiovascular health [245], elevated body weight, increased waist circumference and a lower percentage of lean body mass [246–248].

In our current context of mental health, it is noteworthy that a diet rich in potassium (compared to the DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) and a separate group in a high-calcium diet) was found to improve depression, tension, energy and the Profile of Mood States global score in otherwise healthy adults over the course of 1 month [249]. Also relevant to mental health is a specific physiological change induced by a high-acid load, fast-food type diet. In otherwise healthy adults who consumed an acidic, Western-type diet for 9 days, researchers neutralized the diet with bicarbonate supplements (while subjects maintained the high-acid-load diet) and found that cortisol levels were reduced significantly vs controls maintaining the diet [250]. This result suggests that the high acid load itself is a stressor because cortisol elevation can contribute to inflammation, oxidative stress and lowered mood states [251].

Because the acid–base balance in human blood and other tissue is so tightly regulated, with the exceptions of kidney disease and acute, overt metabolic acidosis, it would be tempting to dismiss the relevancy of dietary factors in regard to their ability to influence pH in and around tissue. However, despite unaltered blood pH, the chronic administration of oral bicarbonate has been shown to increase the extracellular pH of tumors, subsequently reducing the in vivo number and size of tumor metastases. Ultimately in those studies, the reductions in metastases after oral bicarbonate led to increased survival rates of the animals with tumors [252, 253]. In the general population, dietary acid load is associated with lower serum bicarbonate levels [254]. Returning to mental health, it has been shown that the ability of inhaled carbon dioxide to induce fear can be diminished by systemically administered bicarbonate. The amygdala is a highly sensitive chemosensor and contains within it the acid-sensing ion channel 1a (ASIC1a). Direct reductions of pH within the amygdala can evoke fear behavior, whereas inhibition of the ASIC1a receptor has been shown to have antidepressant-like effects in various stress models [255, 256].

Could there be connections between behavior, dietary acid load (and the low end of the normal physiological blood pH range from 7.36 to 7.38), ASIC1a sensitivity and the low serum bicarbonate levels associated with dietary acid load? Perhaps. In the meantime, we do know that potassium-rich diets are less frequently consumed by people with depression [257] and those in lower SES groups [258]. This is an area ripe for research. Related to this topic is the emerging research showing that even mild states of dehydration can negatively influence mood and cognition [259].

An aspect of evolutionary medicine that has ignited a spark in the international research community is a possible connection between the microbiome and mental health. This area of research, at least in its contemporary tone, has many of its original roots in the 1980s hygiene hypothesis, that which suggested that the global rise in allergic disease could be related to diminished opportunity for early-life exposure to pathogenic microbe exposure via increased hygiene and use of antibiotics as well as smaller family size [260]. A decade later, after a landmark 1998 paper by Swedish physician Agnes Wold, the focus shifted toward a more general gut microbial deprivation hypothesis, one that included “low exposure to bacteria via food or the environment in general. All this results in an ‘abnormally’ stable microflora” in Westernized nations [261]. The traditional focus on harmful microbes shifted toward lactic acid bacteria and commensals, with novel scientific frameworks bridging the immune system to emotional health via nonpathogenic microbes [262, 263].

The shift toward an abnormally stable (inflammatory) gut microbiota in Westernized nations became more evident when sophisticated 16S rRNA sequencing techniques allowed detailed stool analyses to be conducted. The results of recent studies have consistently shown that, compared to Westernized urbanites, rural dwellers and hunter-gatherers in Africa and South America have higher levels of microbial richness and diversity. The available evidence suggests that diet, rather than hygiene per se, is the key component to microbial diversity [264–267]. The results of analysis of the microbiome within ancient human coprolite (paleostool) samples indicate more alignment with the modern hunter-gatherer than with the urban dweller in a developed nation [268]. Because ancestral diets seem to set up a gut microbial diversity that is distinct from that currently being associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes [269], we once again arrive at a list of further questions pertaining to the ways in which traditional diets influence mental health.

Scientific interest in lifestyle medicine in general, and nutritional influences related to DOHaD in particular, has grown rapidly in the past several years [270, 271]. These discussions have often focused on obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and allergic diseases. Yet, there are still only limited discussions related to parental and early-life nutrition, epigenetic changes, microevolution, life-course and even transgenerational mental health [272–274]. Children born preterm (vs peers delivered at full term) are at significantly higher risk for developing mental disorders [275]; therefore, studies showing that healthy diets, at the time of conception [276] or during pregnancy [277], are associated with reduced risk of preterm delivery may have enormous implications for mental health. Although allergy is most often the first NCD to present itself in the clinical realm, subtle and even not-so-subtle behavioral alterations may predict subsequent allergic disease risk [278, 279].

It is not our desire to privilege mental health in the DOHaD discussions; rather, we wish to highlight the notion that a broader view is required, one that avoids silos and encourages collaboration. It seems very likely that the same evolutionary mismatch implicated in the global rise in allergic and autoimmune diseases is not distinct from that which seems to be at play in mental disorders [280]. Early-life immune programming via diet and microbes appears to be a universal application related to NCDs. The recent evidence showing that unhealthy maternal dietary choices predict subsequent childhood behavioral problems [70] is both groundbreaking and a source of optimism. It indicates that, despite the environmental challenges discussed earlier, things can be fixed. Indeed, there is an increasing sense of optimism regarding the opportunities for the prevention of mental disorders globally [281, 282].

Summary

Over the past several years, there has been a rapid growth in high-quality research related to nutrition and mental health. An area that has suffered neglect is finally starting to take shape, albeit in a preliminary fashion. Given the global changes described above—urbanicity, climate change and the globalization of the food industry resulting in profound shifts from traditional dietary patterns—there is a sense of urgency to bringing more efficiency and strength to the process of determining the ways in which overall dietary patterns, specific nutritional elements and/or multinutrient interventions can influence mental health.

Compromised mental health in both the broad sense (quality of life) and the more narrow clinical sense (disorders diagnosable based on the definitions published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) is highly comorbid with NCDs, and poor physical health is a particularly strong predictor of poor mental health [283]. Moreover, many of the high-prevalence NCDs share a multitude of underlying pathophysiological pathways with mental illnesses, including immune dysfunction and oxidative stress [59]. One need only pick a medical specialty, from cardiology and dermatology to gastroenterology and rheumatology, and it is plain to see how mental health presents itself as a variable of importance. However, nutrition is also emerging as a variable that uniquely interfaces with both mental health and some of the more notable conditions within these disciplines. Put another way, emerging research suggests that nutrition not only matters directly with regard to the conditions treated within various medical disciplines but also has the potential to influence mental outlook and mental disorders (improving or compromising, depending on intake) that can otherwise contribute to the ultimate outcomes of what are viewed as physical illnesses [284]. We cannot ignore this, particularly as it is becoming increasingly clear that diminished mental outlook and elevated perceptions of stress are drivers of unhealthy eating habits [285–287].

It is not the purpose of our discussion here concerning the interface between nutritional psychiatry and physiological anthropology to systematically review the outcomes and/or potential pathophysiological pathways in minute detail, nor is it to provide a critical assessment of the state of the nutritional psychiatry science in the context of current evidence-based mental health interventions. Our primary message is that the field of nutritional psychiatry is rapidly developing and that, although for the moment it primarily involves global researchers in the fields of nutrition, mental health, population health and epidemiology, this list will surely expand.

Emerging groups such as the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research aim to foster awareness, collaboration and ultimately meaningful clinical translation. Nutrition does not stand alone; it is intimately woven throughout social, cultural, economic, technological, behavioral and other (ancestral past vs present) environmental fabrics with which physiological anthropology concerns itself. As we have tried to make clear in this review, nutritional psychiatry is not a psychiatric specialty per se; on the contrary, the emerging research on the topic has been driven by an eclectic group of specialists in a wide variety of disciplines.

Time is no longer on the side of researchers. Global urbanization and an impending mental health crisis are a tandem juggernaut moving at rapid speed. Its destructive force will not be slowed down by additional silo-style research. Although growing in quality and providing cause for optimism, the current research remains scattered in various disciplines and lacks the collective push that is required in the process of translational medicine. Research studies published in isolation, no matter how elegant, ultimately make the job of translation and policy-making more difficult. We can surely conclude that things do not get better, in the scientific sense, by further neglect and disorganization of approach.

References

Seto KC, Güneralp B, Hutyra LR: Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109: 16083-16088.

Nations U: World Urbanization Prospects (2011 revision). 2012, New York: Author

Cyril S, Oldroyd JC, Renzaho A: Urbanisation, urbanicity, and health: a systematic review of the reliability and validity of urbanicity scales. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13: 513

Zhai FY, Du SF, Wang ZH, Zhang JG, Du WW, Popkin BM: Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes Rev. 2014, 15 (Suppl 1): 16-26.

Levine JA, McCrady SK, Boyne S, Smith J, Cargill K, Forrester T: Non-exercise physical activity in agricultural and urban people. Urban Stud. 2011, 48: 2417-2427.

Delisle H, Ntandou-Bouzitou G, Agueh V, Sodjinou R, Fayomi B: Urbanisation, nutrition transition and cardiometabolic risk: the Benin study. Br J Nutr. 2012, 107: 1534-1544.

Ng SW, Howard AG, Wang HJ, Su C, Zhang B: The physical activity transition among adults in China: 1991–2011. Obes Rev. 2014, 15 (Suppl 1): 27-36.

Bedrosian TA, Nelson RJ: Influence of the modern light environment on mood. Mol Psychiatry. 2013, 18: 751-757.

Popkin BM: Contemporary nutritional transition: determinants of diet and its impact on body composition. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011, 70: 82-91.

Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW: Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012, 70: 3-21.

Richardson AS, Boone-Heinonen J, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P: Are neighbourhood food resources distributed inequitably by income and race in the USA?. Epidemiological findings across the urban spectrum. BMJ Open. 2012, 2: e000698

Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Burstein R, Murray CJ, Vos T: Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013, 382: 1575-1586.

Baxter AJ, Patton G, Scott KM, Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA: Global epidemiology of mental disorders: What are we missing?. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e65514

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380: 2197-2223.

Jacobi F, Höfler M, Siegert J, Mack S, Gerschler A, Scholl L, Busch MA, Hapke U, Maske U, Seiffert I, Gaebel W, Maier W, Wagner M, Zielasek J, Wittchen HU: Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: the Mental Health Module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. in press. doi:10.1002/mpr.1439

Lederbogen F, Kirsch P, Haddad L, Streit F, Tost H, Schuch P, Wüst S, Pruessner JC, Rietschel M, Deuschle M, Meyer-Lindenberg A: City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature. 2011, 474: 498-501.

Penkallas AM, Kohler S: Urbanicity and mental health in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Mental Health. in press

Yiengprugsawan V, Caldwell BK, Lim LL, Seubsman S, Sleigh AC: Lifecourse urbanization, social demography, and health outcomes among a national cohort of 71,516 adults in Thailand. Int J Popul Res. 2011, 2011: 464275

Prina AM, Ferri CP, Guerra M, Brayne C, Prince M: Prevalence of anxiety and its correlates among older adults in Latin America, India and China: cross-cultural study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011, 99: 485-491.

Prina AM, Ferri CP, Guerra M, Brayne C, Prince M: Co-occurrence of anxiety and depression amongst older adults in low- and middle-income countries: findings from the 10/66 study. Psychol Med. 2011, 41: 2047-2056.

Trivedi JK, Sareen H, Dhyani M: Rapid urbanization - its impact on mental health: a south Asian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008, 50: 161-165.

Jacka FN, Sacks G, Berk M, Allender S: Food policies for physical and mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2014, 14: 132

Redshaw CH, Stahl-Timmins WM, Fleming LE, Davidson I, Depledge MH: Potential changes in disease patterns and pharmaceutical use in response to climate change. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2013, 16: 285-320.

Dewing S, Tomlinson M, le Roux IM, Chopra M, Tsai AC: Food insecurity and its association with co-occurring postnatal depression, hazardous drinking, and suicidality among women in peri-urban South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2013, 150: 460-465.

Melchior M, Chastang JF, Falissard B, Galéra C, Tremblay RE, Côté SM, Boivin M: Food insecurity and children’s mental health: a prospective birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e52615

Bloom SR, Kuhajda FP, Laher I, Pi-Sunyer X, Ronnett GV, Tan TM, Weigle DS: The obesity epidemic: pharmacological challenges. Mol Interv. 2008, 8: 82-98.

Hidaka BH: Depression as a disease of modernity: explanations for increasing prevalence. J Affect Disord. 2012, 140: 205-214.

Colla J, Buka S, Harrington D, Murphy JM: Depression and modernization: a cross-cultural study of women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006, 41: 271-279.

Logan AC, Selhub EM: Vis Medicatrix naturae: does nature “minister to the mind”?. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012, 6: 11

Streit F, Haddad L, Paul T, Frank J, Schäfer A, Nikitopoulos J, Akdeniz C, Lederbogen F, Treutlein J, Witt S, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Rietschel M, Kirsch P, Wüst S: A functional variant in the neuropeptide S receptor 1 gene moderates the influence of urban upbringing on stress processing in the amygdala. Stress. 2014, 17: 352-361.

Peen J, Schoevers RA, Beekman AT, Dekker J: The current status of urban–rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010, 121: 84-93.

Rudolph KE, Stuart EA, Glass TA, Merikangas KR: Neighborhood disadvantage in context: the influence of urbanicity on the association between neighborhood disadvantage and adolescent emotional disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014, 49: 467-475.

Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, Kessler RC, Kohn R, Offord DR, Ustun TB, Vicente B, Vollebergh WA, Walters EE, Wittchen HU: The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Aff. 2003, 22: 122-133.

Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, Wan X, Yu S, Jiang Y, Naghavi M, Vos T, Wang H, Lopez AD, Murray CJ: Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013, 381: 1987-2015.

Lee KS, Park JH: Burden of disease in Korea during 2000–10. J Public Health. 2014, 36: 225-234.

Mokdad AH, Jaber S, Aziz MI, AlBuhairan F, AlGhaithi A, AlHamad NM, Al-Hooti SN, Al-Jasari A, AlMazroa MA, AlQasmi AM, Alsowaidi S, Asad M, Atkinson C, Badawi A, Bakfalouni T, Barkia A, Biryukov S, El Bcheraoui C, Daoud F, Forouzanfar MH, Gonzalez-Medina D, Hamadeh RR, Hsairi M, Hussein SS, Karam N, Khalifa SE, Khoja TA, Lami F, Leach-Kemon K, Memish ZA: The state of health in the Arab world, 1990–2010: an analysis of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. Lancet. 2014, 383: 309-320.

Sartorius N, Cimino L: The co-occurrence of diabetes and depression: an example of the worldwide epidemic of comorbidity of mental and physical illness. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2012, 41: 430-431.

Lin CH, Lee YY, Liu CC, Chen HF, Ko MC, Li CY: Urbanization and prevalence of depression in diabetes. Public Health. 2012, 126: 104-111.

van Reedt Dortland AK, Giltay EJ, van Veen T, Zitman FG, Penninx BW: Longitudinal relationship of depressive and anxiety symptoms with dyslipidemia and abdominal obesity. Psychosom Med. 2013, 75: 83-89.

Thurston RC, Rewak M, Kubzansky LD: An anxious heart: anxiety and the onset of cardiovascular diseases. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013, 55: 524-537.

Nielsen TJ, Vestergaard M, Christensen B, Christensen KS, Larsen KK: Mental health status and risk of new cardiovascular events or death in patients with myocardial infarction: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013, 3: e003045

Balázs J, Miklósi M, Keresztény A, Hoven CW, Carli V, Wasserman C, Apter A, Bobes J, Brunner R, Cosman D, Cotter P, Haring C, Iosue M, Kaess M, Kahn JP, Keeley H, Marusic D, Postuvan V, Resch F, Saiz PA, Sisask M, Snir A, Tubiana A, Varnik A, Sarchiapone M, Wasserman D: Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety: psychopathology, functional impairment and increased suicide risk. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013, 54: 670-677.

Berk M, Sarris J, Coulson CE, Jacka FN: Lifestyle management of unipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2013, 443: 38-54.

Penn E, Tracy DK: The drugs don’t work? Antidepressants and the current and future pharmacological management of depression. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2012, 2: 179-188.

Khan A, Faucett J, Lichtenberg P, Kirsch I, Brown WA: A systematic review of comparative efficacy of treatments and controls for depression. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e41778

Spielmans GI, Kirsch I: Drug approval and drug effectiveness. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014, 10: 741-766.

Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, Hollon SD, Andersson G: Efficacy of cognitive-behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 196: 173-178.

Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS: A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2013, 58: 376-385.

Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM, Honyashiki M, Shinohara K, Imai H, Chen P, Hunot V, Churchill R: Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. in press. doi:10.1111/acps.12275

Cuijpers P, Turner EH, Mohr DC, Hofmann SG, Andersson G, Berking M, Coyne J: Comparison of psychotherapies for adult depression to pill placebo control groups: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014, 44: 685-695.

Thomas L, Kessler D, Campbell J, Morrison J, Peters TJ, Williams C, Lewis G, Wiles N: Prevalence of treatment-resistant depression in primary care: cross-sectional data. Br J Gen Pract. 2013, 63: e852-e858.

Jacka FN, Reavley NJ: Prevention of mental disorders: evidence, challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2014, 12: 75

Jacka FN, Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ, Butterworth P: Dietary patterns and depressive symptoms over time: examining the relationships with socioeconomic position, health behaviours and cardiovascular risk. PLoS One. 2014, 9: e87657

Gesch B: Adolescence: Does good nutrition = good behavior?. Nutr Health. 2014, 22: 55-65.

Sihvola N, Korpela R, Henelius A, Holm A, Huotilainen M, Müller K, Poussa T, Pettersson K, Turpeinen A, Peuhkuri K: Breakfast high in whey protein or carbohydrates improves coping with workload in healthy subjects. Br J Nutr. 2013, 110: 1712-1721.

Belcaro G, Luzzi R, Dugall M, Ippolito E, Saggino A: Pycnogenol® improves cognitive function, attention, mental performance and specific professional skills in healthy professionals age 35–55. J Neurosurg Sci. in press

Sarris J, O’Neil A, Coulson CE, Schweitzer I, Berk M: Lifestyle medicine for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2014, 14: 107

Moylan S, Berk M, Dean OM, Samuni Y, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, Hayley AC, Pasco JA, Anderson G, Jacka FN, Maes M: Oxidative & nitrosative stress in depression: Why so much stress?. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014, 45C: 46-62.

Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Pasco JA, Moylan S, Allen NB, Stuart AL, Hayley AC, Byrne ML, Maes M: So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?. BMC Med. 2013, 11: 200

Sizonenko SV, Babiloni C, Sijben JW, Walhovd KB: Brain imaging and human nutrition: which measures to use in intervention studies?. Adv Nutr. 2013, 4: 554-556.

Jacka FN, Mykletun A, Berk M, Bjelland I, Tell GS: The association between habitual diet quality and the common mental disorders in community-dwelling adults: the Hordaland Health Study. Psychosom Med. 2011, 73: 483-490.

Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, Williams LJ, Hodge AM, O’Reilly SL, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M: Association of western and traditional diets with depression and anxiety in women. Am J Psychiatry. 2010, 167: 305-311.

Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, Schlatter J, Lahortiga F, Serra Majem L, Martínez-González MA: Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009, 66: 1090-1098.

Skarupski KA, Tangney CC, Li H, Evans DA, Morris MC: Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013, 17: 441-445.

Rienks J, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD: Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-aged women: results from a large community-based prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013, 67: 75-82.

Lai JS, Hiles S, Bisquera A, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Attia J: A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014, 99: 181-197.

Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, Sergentanis IN, Kosti R, Scarmeas N: Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013, 74: 580-591.

Nanri A, Mizoue T, Poudel-Tandukar K, Noda M, Kato M, Kurotani K, Goto A, Oba S, Inoue M, Tsugane S, Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group: Dietary patterns and suicide in Japanese adults: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Br J Psychiatry. 2013, 203: 422-427.

Pham NM, Nanri A, Kurotani K, Kuwahara K, Kume A, Sato M, Hayabuchi H, Mizoue T: Green tea and coffee consumption is inversely associated with depressive symptoms in a Japanese working population. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17: 625-633. A published erratum appears in Public Health Nutr 2014, 17:715

Jacka FN, Ystrom E, Brantsaeter AL, Karevold E, Roth C, Haugen M, Meltzer HM, Schjolberg S, Berk M: Maternal and early postnatal nutrition and mental health of offspring by age 5 years: a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013, 52: 1038-1047.

Solfrizzi V, Panza F: Mediterranean diet and cognitive decline. A lesson from the whole-diet approach: what challenges lie ahead?. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014, 39: 283-286.

Martínez-Lapiscina EH, Clavero P, Toledo E, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, San Julián B, Sanchez-Tainta A, Ros E, Valls-Pedret C, Martinez-Gonzalez MÁ: Mediterranean diet improves cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013, 84: 1318-1325.

Lang UE, Borgwardt S: Molecular mechanisms of depression: perspectives on new treatment strategies. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013, 31: 761-777.

Yu Y, Wang R, Chen C, Du X, Ruan L, Sun J, Li J, Zhang L, O’Donnell JM, Pan J, Xu Y: Antidepressant-like effect of trans-resveratrol in chronic stress model: behavioral and neurochemical evidences. Psychiatr Res. 2013, 47: 315-322.

Pathak L, Agrawal Y, Dhir A: Natural polyphenols in the management of major depression. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013, 22: 863-880.

Sullivan EL, Nousen EK, Chamlou KA: Maternal high fat diet consumption during the perinatal period programs offspring behavior. Physiol Behav. 2014, 123: 236-242.

Sharma S, Zhuang Y, Gomez-Pinilla F: High-fat diet transition reduces brain DHA levels associated with altered brain plasticity and behaviour. Sci Rep. 2012, 2: 431

Fernandes C, Grayton H, Poston L, Samuelsson AM, Taylor PD, Collier DA, Rodriguez A: Prenatal exposure to maternal obesity leads to hyperactivity in offspring. Mol Psychiatry. 2012, 17: 1159-1160.

Pase CS, Roversi K, Trevizol F, Roversi K, Kuhn FT, Schuster AJ, Vey LT, Dias VT, Barcelos RC, Piccolo J, Emanuelli T, Bürger ME: Influence of perinatal trans fat on behavioral responses and brain oxidative status of adolescent rats acutely exposed to stress. Neuroscience. 2013, 247: 242-252.

Perveen T, Hashmi BM, Haider S, Tabassum S, Saleem S, Siddiqui MA: Role of monoaminergic system in the etiology of olive oil induced antidepressant and anxiolytic effects in rats. ISRN Pharmacol. 2013, 2013: 615685

Maric T, Woodside B, Luheshi GN: The effects of dietary saturated fat on basal hypothalamic neuroinflammation in rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2014, 36: 35-45.

Francis HM, Stevenson RJ: Higher reported saturated fat and refined sugar intake is associated with reduced hippocampal-dependent memory and sensitivity to interoceptive signals. Behav Neurosci. 2011, 125: 943-955.

Papadopoulou A, Markianos M, Christodoulou C, Lykouras L: Plasma total cholesterol in psychiatric patients after a suicide attempt and in follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2013, 148: 440-443.

Almeida OP, Yeap BB, Hankey GJ, Golledge J, Flicker L: HDL cholesterol and the risk of depression over 5 years. Mol Psychiatry. 2014, 19: 637-638.

Balanzá-Martínez V, Fries GR, Colpo GD, Silveira PP, Portella AK, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Kapczinski F: Therapeutic use of omega-3 fatty acids in bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011, 11: 1029-1047.

Matsuoka Y, Nishi D, Yonemoto N, Hamazaki K, Hashimoto K, Hamazaki T: Omega-3 fatty acids for secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder after accidental injury: an open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010, 30: 217-219.

Su KP, Wang SM, Pae CU: Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013, 22: 1519-1534.

Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, Mackinnon A, McGorry PD, Berger GE: Long-chain ω-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010, 67: 146-154.

Rucklidge JJ, Johnstone J, Kaplan BJ: Magic bullet thinking–why do we continue to perpetuate this fallacy?. Br J Psychiatry. 2013, 203: 154

Rucklidge JJ, Kaplan BJ: Broad-spectrum micronutrient formulas for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms: a systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013, 13: 49-73.

Solati Z, Jazayeri S, Tehrani-Doost M, Mahmoodianfard S, Gohari MR: Zinc monotherapy increases serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels and decreases depressive symptoms in overweight or obese subjects: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled tria. Nutr Neurosci. in press. doi:10.1179/1476830513Y.0000000105

Swardfager W, Herrmann N, Mazereeuw G, Goldberger K, Harimoto T, Lanctôt KL: Zinc in depression: a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013, 74: 872-878.

Młyniec K, Budziszewska B, Reczyński W, Doboszewska U, Pilc A, Nowak G: Zinc deficiency alters responsiveness to antidepressant drugs in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2013, 65: 579-592.

Eder K, Kirchgessner M: Dietary fat influences the effect of zinc deficiency on liver lipids and fatty acids in rats force-fed equal quantities of diet. J Nutr. 1994, 124: 1917-1926.

Sadli N, Ackland ML, De Mel D, Sinclair AJ, Suphioglu C: Effects of zinc and DHA on the epigenetic regulation of human neuronal cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012, 29: 87-98.

Rucklidge JJ, Frampton CM, Gorman B, Boggis A: Vitamin-mineral treatment of ADHD in adults: a 1-year naturalistic follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Atten Disord. in press. doi:10.1177/1087054714530557

Pipingas A, Camfield DA, Stough C, Cox KH, Fogg E, Tiplady B, Sarris J, White DJ, Sali A, Wetherell MA, Scholey AB: The effects of multivitamin supplementation on mood and general well-being in healthy young adults: a laboratory and at-home mobile phone assessment. Appetite. 2013, 69: 123-136.

Rucklidge JJ, Harris AL, Shaw IC: Are the amounts of vitamins in commercially available dietary supplement formulations relevant for the management of psychiatric disorders in children?. N Z Med J. 2014, 127: 73-85.

Dickinson A, Blatman J, El-Dash N, Franco JC: Consumer usage and reasons for using dietary supplements: report of a series of surveys. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014, 33: 176-182.

Davison KM, Kaplan BJ: Nutrient- and non-nutrient-based natural health product (NHP) use in adults with mood disorders: prevalence, characteristics and potential for exposure to adverse events. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013, 13: 80

Astiz M, Diz-Chaves Y, Garcia-Segura LM: Sub-chronic exposure to the insecticide dimethoate induces a proinflammatory status and enhances the neuroinflammatory response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide in the hippocampus and striatum of male mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013, 272: 263-271.

McCann D, Barrett A, Cooper A, Crumpler D, Dalen L, Grimshaw K, Kitchin E, Lok K, Porteous L, Prince E, Sonuga-Barke E, Warner JO, Stevenson J: Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3-year-old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2007, 370: 1560-1567. A published erratum appears in Lancet 2007, 370:1542

Quines CB, Rosa SG, Da Rocha JT, Gai BM, Bortolatto CF, Duarte MM, Nogueira CW: Monosodium glutamate, a food additive, induces depressive-like and anxiogenic-like behaviors in young rats. Life Sci. 2014, 107: 27-31.

Cong WN, Wang R, Cai H, Daimon CM, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Bohr VA, Turkin R, Wood WH, Becker KG, Moaddel R, Maudsley S, Martin B: Long-term artificial sweetener acesulfame potassium treatment alters neurometabolic functions in C57BL/6 J mice. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e70257

Peters SL, Biesiekierski JR, Yelland GW, Muir JG, Gibson PR: Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity – an exploratory clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014, 39: 1104-1112.

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, Rahman A: No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007, 370: 859-877.

Gubata ME, Urban N, Cowan DN, Niebuhr DW: A prospective study of physical fitness, obesity, and the subsequent risk of mental disorders among healthy young adults in army training. J Psychosom Res. 2013, 75: 43-48.

Sener U, Ucok K, Ulasli AM, Genc A, Karabacak H, Coban NF, Simsek H, Cevik H: Evaluation of health-related physical fitness parameters and association analysis with depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis. in press. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12237

Searle A, Calnan M, Lewis G, Campbell J, Taylor A, Turner K: Patients’ views of physical activity as treatment for depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011, 61: 149-156.

Weinstein AA, Deuster PA, Francis JL, Beadling C, Kop WJ: The role of depression in short-term mood and fatigue responses to acute exercise. Int J Behav Med. 2010, 17: 51-57.

Ekkekakis P, Parfitt G, Petruzzello SJ: The pleasure and displeasure people feel when they exercise at different intensities: decennial update and progress towards a tripartite rationale for exercise intensity prescription. Sports Med. 2011, 41: 641-671.

Annesi J: Relations of self-motivation, perceived physical condition, and exercise-induced changes in revitalization and exhaustion with attendance in women initiating a moderate cardiovascular exercise regimen. Women Health. 2005, 42: 77-93.

Kwan BM, Bryan A: In-task and post-task affective response to exercise: translating exercise intentions into behaviour. Br J Health Psychol. 2010, 15: 115-131.

Huck CJ, Johnston CS, Beezhold BL, Swan PD: Vitamin C status and perception of effort during exercise in obese adults adhering to a calorie-reduced diet. Nutrition. 2013, 29: 42-45.

McMillan L, Owen L, Kras M, Scholey A: Behavioural effects of a 10-day Mediterranean diet: results from a pilot study evaluating mood and cognitive performance. Appetite. 2011, 56: 143-147.

Shahar DR, Houston DK, Hue TF, Lee JS, Sahyoun NR, Tylavsky FA, Geva D, Vardi H, Harris TB: Adherence to Mediterranean diet and decline in walking speed over 8 years in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012, 60: 1881-1888.

Zbeida M, Goldsmith R, Shimony T, Vardi H, Naggan L, Shahar DR: Mediterranean diet and functional indicators among older adults in non-Mediterranean and Mediterranean countries. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014, 18: 411-418.

Kivimäki M, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Hamer M, Akbaraly TN, Kumari M, Jokela M, Virtanen M, Lowe GD, Ebmeier KP, Brunner EJ, Singh-Manoux A: Long-term inflammation increases risk of common mental disorder: a cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014, 19: 149-150.

Moylan S, Maes M, Wray NR, Berk M: The neuroprogressive nature of major depressive disorder: pathways to disease evolution and resistance, and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2013, 18: 595-606.

Marazziti D, Rutigliano G, Baroni S, Landi P, Dell’Osso L: Metabolic syndrome and major depression. CNS Spectr. in press. doi:10.1017/S1092852913000667

Bested AC, Logan AC, Selhub EM: Intestinal microbiota, probiotics and mental health: from Metchnikoff to modern advances: Part II – contemporary contextual research. Gut Pathog. 2013, 5: 3

Burnet PW, Cowen PJ: Psychobiotics highlight the pathways to happiness. Biol Psychiatry. 2013, 74: 708-709.

Ohland CL, Kish L, Bell H, Thiesen A, Hotte N, Pankiv E, Madsen KL: Effects of Lactobacillus helveticus on murine behavior are dependent on diet and genotype and correlate with alterations in the gut microbiome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013, 38: 1738-1747.

Selhub EM, Logan AC, Bested AC: Fermented foods, microbiota, and mental health: ancient practice meets nutritional psychiatry. J Physiol Anthropol. 2014, 33: 2

Pallebage-Gamarallage M, Lam V, Takechi R, Galloway S, Clark K, Mamo J: Restoration of dietary-fat induced blood–brain barrier dysfunction by anti-inflammatory lipid-modulating agents. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11: 117

Chang HC, Tai YT, Cherng YG, Lin JW, Liu SH, Chen TL, Chen RM: Resveratrol attenuates high-fat diet-induced disruption of the blood–brain barrier and protects brain neurons from apoptotic insults. J Agric Food Chem. 2014, 62: 3466-3475.

Takechi R, Pallebage-Gamarallage MM, Lam V, Giles C, Mamo JC: Nutraceutical agents with anti-inflammatory properties prevent dietary saturated-fat induced disturbances in blood–brain barrier function in wild-type mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2013, 10: 73

Rahe C, Unrath M, Berger K: Dietary patterns and the risk of depression in adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Nutr. 2014, 53: 997-1013.

Aneshensel CS: Toward explaining mental health disparities. J Health Soc Behav. 2009, 50: 377-394.

Wittayanukorn S, Qian J, Hansen RA: Prevalence of depressive symptoms and predictors of treatment among U.S. adults from 2005 to 2010. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014, 36: 330-336.

Ban L, Gibson JE, West J, Fiaschi L, Oates MR, Tata LJ: Impact of socioeconomic deprivation on maternal perinatal mental illnesses presenting to UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2012, 62: e671-e678.

Rofey DL, Kolko RP, Iosif AM, Silk JS, Bost JE, Feng W, Szigethy EM, Noll RB, Ryan ND, Dahl RE: A longitudinal study of childhood depression and anxiety in relation to weight gain. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2009, 40 (4): 517-526.

Goodman E, Whitaker RC: A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002, 110: 497-504.

Brumpton B, Langhammer A, Romundstad P, Chen Y, Mai XM: The associations of anxiety and depression symptoms with weight change and incident obesity: the HUNT study. Int J Obes. 2013, 37: 1268-1274.

Jeffery AN, Hyland ME, Hosking J, Wilkin TJ: Mood and its association with metabolic health in adolescents: a longitudinal study, EarlyBird 65. Pediatr Diabetes. in press. doi:10.1111/pedi.12125