Abstract

The composition of continental subduction-zone fluids varies dramatically from dilute aqueous solutions at subsolidus conditions to hydrous silicate melts at supersolidus conditions, with variable concentrations of fluid-mobile incompatible trace elements. At ultrahigh-pressure (UHP) metamorphic conditions, supercritical fluids may occur with variable compositions. The water component of these fluids primarily derives from structural hydroxyl and molecular water in hydrous and nominally anhydrous minerals at UHP conditions. While the breakdown of hydrous minerals is the predominant water source for fluid activity in the subduction factory, water released from nominally anhydrous minerals provides an additional water source. These different sources of water may accumulate to induce partial melting of UHP metamorphic rocks on and above their wet solidii. Silica is the dominant solute in the deep fluids, followed by aluminum and alkalis. Trace element abundances are low in metamorphic fluids at subsolidus conditions, but become significantly elevated in anatectic melts at supersolidus conditions. The compositions of dissolved and residual minerals are a function of pressure-temperature and whole-rock composition, which exert a strong control on the trace element signature of liberated fluids. The trace element patterns of migmatic leucosomes in UHP rocks and multiphase solid inclusions in UHP minerals exhibit strong enrichment of large ion lithophile elements (LILE) and moderate enrichment of light rare earth elements (LREE) but depletion of high field strength elements (HFSE) and heavy rare earth elements (HREE), demonstrating their crystallization from anatectic melts of crustal protoliths. Interaction of the anatectic melts with the mantle wedge peridotite leads to modal metasomatism with the generation of new mineral phases as well as cryptic metasomatism that is only manifested by the enrichment of fluid-mobile incompatible trace elements in orogenic peridotites. Partial melting of the metasomatic mantle domains gives rise to a variety of mafic igneous rocks in collisional orogens and their adjacent active continental margins. The study of such metasomatic processes and products is of great importance to understanding of the mass transfer at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels. Therefore, the property and behavior of subduction-zone fluids are a key for understanding of the crust-mantle interaction at convergent plate margins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Findings

Introduction

Continental subduction zones are generally marked by the occurrence of ultrahigh-pressure (UHP) eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks (e.g., Chopin 2003; Liou et al. 2009; Zheng 2012; Hermann and Rubatto 2014). These rocks contain important records of physical and chemical changes that occur at the slab-mantle interface in deep subduction channel. While arc volcanics above oceanic subduction zones are common and indirectly record the composition of oceanic subduction-zone fluids and their action on the mantle wedge (Stern 2002), so far, no arc volcanics have been found above continental subduction zones (e.g., Rumble et al. 2003; Zheng 2009, 2012). This provides evidence for a difference in the nature of crust-mantle interactions between the two types of subduction zones. Traditionally, the composition of oceanic subduction-zone fluids has been deciphered from the composition of arc volcanics (e.g., Tatsumi and Eggins 1995). These rocks exhibit enrichment of large ion lithophile elements (LILE) and light rare earth elements (LREE) relative to the primitive mantle and thus are generally attributed to slab dehydration and element transport at mantle depths of 80 to 130 km. However, the direct study of high-pressure (HP) blueschist- and eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks exhumed from subducted oceanic crust only provides information about the mass transfer at shallow depths of <80 km (e.g., Agard et al. 2009). On the other hand, UHP eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks are prominent in continental subduction zones, providing us with an excellent target to directly study subduction-zone fluids at subarc depths of >80 km (e.g., Zheng, 2009, 2012).

The transfer of crustal components in the form of fluids at subduction zones occurs in several steps, and the agents of mass transfer vary with time and space (e.g., Bebout 2007; Zheng 2012). While aqueous solutions are primarily responsible for extraction of water-soluble incompatible elements such as LILE from subducting crustal rocks (e.g., Hacker 2008; Bebout 2014), hydrous melts play a dominant role in mobilizing water-insoluble incompatible elements such as LREE from the subducting rocks (e.g., Hermann et al. 2006a; Zheng et al. 2011a). The nature of subduction-zone fluids is dictated by dehydration and melting of crustal rocks under different physicochemical conditions. The mobile agents migrate in pervasive and channelized ways at the slab-mantle interface, resulting in geochemical modification of both slab crust and wedge mantle rocks (e.g., Zheng 2012; Bebout 2013). Although we are not able to directly sample pristine fluids from deeply subducted crustal rocks, working backwards from metamorphic, anatectic and magmatic products in UHP metamorphic terranes provides insights into the geochemical property and behavior of subduction-zone fluids at the subarc depths. This overview outlines our present understanding of continental subduction-zone fluids and their implications for chemical geodynamics (Additional file 1 presents the glossary for the subduction factory).

Water in subduction-zone rocks

Water is a key component of subduction-zone rocks and is present as two species: (1) molecular water (H2O) and (2) structural hydroxyl (OH). The structural hydroxyl occurs in hydrous minerals and the point defects of nominally anhydrous minerals (NAMs). While hydrous minerals are the major carrier of water in subducted crustal rocks, NAMs carry trace amounts of water into the mantle. In HP to UHP metamorphic rocks, the molecular water occurs not only in the volume defects of minerals as microscale to nanoscale fluid inclusions, but also at the surface defects of mineral grains at grain boundaries and crystal fractures. Pore fluids are a major source of molecular water at subsolidus metamorphic conditions in metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks, but it is scarce in metaintrusive rocks (Zheng, 2009, 2012). There would be the transformation between structural OH and molecular H2O with P-T changes in HP to UHP metamorphic rocks.

With subduction of crustal rocks to mantle depths, the majority of water is released in the form of molecular water through breakdown of hydrous minerals. Significant amounts of structural hydroxyl and molecular water are also dissolved into NAMs with increasing pressure (Zheng 2009). The maximum solubility of water in the NAMs is achieved at the maximum pressure during subduction to mantle depths (Chen et al. 2011; Gong et al. 2013). During the exhumation of deeply subducted crustal rocks, on the other hand, the water in the NAMs is exsolved due to its decreased solubility with decreasing pressure (Zheng 2009). The liberated water may result in the formation of retrograde hydrous minerals in UHP rocks (Zheng et al. 2003). If exhumation occurs at elevated temperatures, the hydrous UHP minerals such as phengite may break down during decompression, resulting in local anatexis of the UHP rocks (Gao et al. 2012, 2013; Chen et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013).

Subduction-zone fluids are categorized into three types in terms of their H2O contents (e.g., Hermann et al. 2006a; Zheng et al. 2011a): (1) aqueous solution, which contains less than 30 wt. % of solutes; (2) hydrous silicate melt, which contains less than 35 wt. % of dissolved water; and (3) supercritical fluid, which exhibits the complete miscibility between aqueous solution and hydrous melt with variable proportions between the two fluid phases. The aqueous solution and the hydrous melt become progressively miscible with increasing pressure, eventually giving rise to a supercritical fluid above the second critical endpoint at UHP conditions (Manning 2004; Hermann et al. 2006a; Mibe et al. 2011; Adam et al. 2014). In this region, the amount of solutes in the supercritical fluid varies gradually as a function of pressure and temperature (Hack et al. 2007), with a variety of compositions between aqueous solution and hydrous melt (Zheng et al. 2011a; Hermann and Rubatto 2014). On the other hand, the solvus between aqueous solution and hydrous melt might be encountered during decompression of the supercritical fluid, resulting in the separation into aqueous solutions and hydrous melts (Zheng et al. 2011a). This may result in the precipitation of mineral phases depending on the relative solubilties of components before and after the phase separation. The phase separation of supercritical fluids has been directly observed in sophisticated in situ laboratory experiments (Kawamoto et al. 2012). Field-based studies suggested that some multiphase solid inclusions (MSI) may be crystallized from the separated hydrous melts (Ferrando et al. 2005; Frezzotti et al. 2007; Gao et al. 2012), whereas metamorphic zircon and rutile in metamorphic veins inside UHP eclogites may be grown from the separated aqueous solutions (Xia et al. 2010; Zheng et al. 2011b).

During the subduction of crustal rocks, the aqueous solution is generated not only by the prograde breakdown of hydrous minerals such as amphibole, biotite, chlorite, lawsonite, muscovite, serpentine, and zoisite with increasing pressure and temperature (e.g., Schmidt and Poli 2003; Rupke et al. 2004, Spandler and Pirard 2013) but also by the exsolution of molecular water and structural hydroxyl from NAMs (Zheng 2009). While some of these hydrous minerals may be present in small amounts in HP to UHP eclogites, some UHP eclogites may contain neither of these hydrous minerals. Instead, they contain hundreds to thousands of parts per million (ppm) H2O within NAMs such as garnet and pyroxene, not only as structural OH in point defects (Katayama and Nakashima 2003; Xia et al. 2005; Katayama et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2007; Sheng et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2007a) but also as molecular H2O in surface and volume defects (Su et al. 2002; Xiao et al. 2002; Fu et al. 2003; Gao et al. 2007; Ni et al., 2008; Zhang et al. 2008; Meng et al. 2009; Mukherjee and Sachan 2009). Analyses of the total water in NAMs yield the maximum water contents of about 2,500 ppm and about 3,500 ppm, respectively, in garnet and omphacite at UHP conditions (Chen et al. 2011; Gong et al. 2013). At pressures of the mantle transition zone, 1.4 to 1.5 wt % H2O may occur in ringwoodite included in a diamond (Pearson et al. 2014).

The dehydration of subducting crustal rocks may occur at P-T conditions on and above the wet solidus (Figure 1), resulting in anatexis of HP to UHP metamorphic rocks. This has been observed in many UHP metamorphic rocks where anatexis takes place at relatively high temperatures due to breakdown of hydrous UHP minerals such as phengite during decompression (Gao et al. 2012, 2013; Chen et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013). In a series of experiments on the rheology of eclogite at 1,300 to 1,500 K and 3.0 GPa, on the other hand, Zhang et al. (2004) observed partial melting of an eclogite that contained no hydrous minerals but only H2O of up to 300 ppm in garnet, 1,000 to 1,300 ppm in omphacite and 3,000 to 4,000 ppm in rutile. After the experiments, they measured almost no OH in garnet and only 600 to 700 ppm H2O in omphacite. This indicates the significant loss of water from both garnet and omphacite, demonstrating that water is preferentially enriched in hydrous melts. Likewise, minor amounts of water in feldspar and quartz of the deep continental crust may be accumulated in intergrain boundaries to facilitate partial melting of granitoids at temperatures hundreds of degrees below the dry solidus (Seaman et al. 2013). Therefore, dehydration melting can be caused not only by the breakdown of hydrous minerals but also by the exsolution of structural hydroxyl from NAMs. In either case, water is highly incompatible during partial melting of crustal and mantle rocks.

Metamorphic facies and stability fields of hydrous minerals under subduction-zone conditions. Metamorphism above the coesite/quartz transition line is referred as ultrahigh-pressure (UHP) metamorphism, whereas metamorphism below the coesite/quartz transition line is referred as high-pressure (HP) metamorphism. Dashed lines denote the geothermal gradients at 5°C/km and 15°C/km, respectively, in subduction zones. Solid dark-red curves denote the wet solidi for basalt (Schmidt and Poli 1998) and granite (Holtz et al., 2001), with circles for the second critical endpoints of the basalt-water system (after Mibe et al. 2011) and the granite-water system (after Hermann et al. 2006a). Mineral abbreviations: Amp, amphibole; Chl, chlorite; Cld, chloritoid; Law, lawsonite; Zo, zoisite. Lithological abbreviations: GS, greenschist-facies; EB, epidote blueschist-facies; EA, epidote amphibolite-facies.

The release of fluids is a key to physicochemical processes at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels. As illustrated in Figure 1, this primarily depends on the thermal structure of subduction zones. As documented by phase equilibrium calculations (Peacock and Wang, 1999; Kerrick and Connolly 2001a, 2001b), hot subduction at high geotherms of >15°C/km results in significant dehydration at shallow depths of <60 km, with abundant occurrences of greenschist- to amphibolite-facies metamorphic rocks but rare occurrences of arc volcanics above such hot subduction zones. In the extreme case, partial melting of subducting seafloor sediment is significant at upper amphibolite- to granulite-facies conditions, but the pressure is too low to induce partial melting of the mantle wedge. In contrast, cold subduction at low geotherms of 5 to 10°C/km leads to insignificant dehydration at the shallow depths, with significant occurrences of HP blueschist- to eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks and arc volcanics above such cold subduction zones (Peacock and Wang 1999). It is the cold subduction that leads to the insignificant dehydration at the shallow depths but the significant dehydration and anatexis at the subarc depths >80 km. Continental subduction generally takes place at low geotherms, yielding UHP metamorphic rocks that provide direct samples for the study of subduction-zone fluids at the subarc depths.

Composition of continental subduction-zone fluids

Experimental constraints

The solute composition of subduction-zone fluids is a function of the following three variables: (1) element solubility, (2) temperature, and (3) pressure. The amount of water in fluids is inversely correlated with that of solutes and thus also changes as a strong function of pressure and temperature. The major solutes are Si, Al, and alkalis (Na, K) with minor amounts of Ca, Fe, and Mg (Hermann et al. 2013). While Al is not significantly fractionated during partial melting, the aqueous solution preferentially dissolves Si and is characterized by a positive spike in alkalis. The aqueous solution and the hydrous melt have different capacities of dissolving and transporting trace elements during subduction-zone processes (e.g., Hermann et al. 2006a; Zheng et al. 2011a).

Figure 2 shows the experimentally determined concentration of major and trace elements in aqueous solutions and hydrous melts at HP to UHP conditions relative to the pelitic protolith that has a common crustal composition (Additional file 2: Table S1). Upon water-rock interaction and hydration melting, water-soluble incompatible trace elements such as LILE and U are preferentially enriched in aqueous solutions; LREE and Th tend to enter hydrous melts whereas heavy rare earth elements (HREE) are highly enriched in residues. The trace element concentrations of aqueous solutions are at least an order of magnitude lower than those of hydrous melts. However, the common water-soluble or fluid-mobile elements like LILE and LREE are not enriched in these fluids if residual assemblages are enriched in phengite and allanite, respectively. Uranium and Nb are more enriched in the fluid phase compared to Th and Ta.

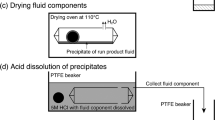

Experimentally determined element distribution of fluids normalized to the starting materials of pelitic composition. The major and trace element compositions of the starting materials and the fluids produced at HP to UHP conditions are given in Additional file 2: Table S1. Blue-green curves denote aqueous solutions, where data at 2.2 GPa are after Spandler et al. (2007); data at 2.5 to 4.5 GPa and 600 and 700°C are after Hermann and Spandler (2008) for major elements and Table S1 in Additional file 2 for trace elements from the same experiments. Red-orange curves denote hydrous melts with data after Hermann and Rubatto (2009).

Although mineral assemblages in the crustal rocks of mafic to felsic compositions are very different at low pressures, they converge to a common paragenesis at UHP conditions that is composed of coesite, garnet, clinopyroxene, phengite, and kyanite and accessory rutile, zircon, apatite, and allanite or monazite (e.g., Schmidt et al. 2004a; Hermann et al. 2006a; Schertl and O’Brien 2013). The proportions of these UHP metamorphic minerals are a function of whole-rock composition and P-T conditions, which exert a primary control on the trace element composition of coexisting fluid phases. LILE are primarily controlled by phengite, and therefore, in K-rich rocks containing high amounts of phengite, LILE are not necessarily enriched in the aqueous solution with respect to the dehydrated residue (Figure 2). In K-poor rocks, on the other hand, phengite may completely break down and thus no longer be a host mineral for LILE. In this case, the liberated fluids are highly enriched in LILE with respect to the dehydrated residue.

Garnet is a major host of HREE, resulting in depletion of HREE in aqueous solutions and hydrous melts (Figure 2). The major hosts for LREE, Th, and partly U are allanite and monazite. As allanite and monazite preferentially incorporate Th over U (Klimm et al. 2008; Skora and Blundy 2012; Stepanov et al. 2012), the coexisting fluid is characterized by a relative enrichment of U over Th (Figure 2). Significant enrichment of Th is only possible by allanite/monazite dissolution in hydrous melts (Hermann 2002; Klimm et al. 2008; Stepanov et al. 2012). On the other hand, U is a water-soluble element and very susceptible to dissolution from crustal rocks into aqueous solutions. Thus, the Th/U ratios of subduction-zone fluids may provide a distinction between the aqueous solutions and the hydrous melts at the slab-mantle interface in the subduction channel.

Rutile is a major host of high-field-strength elements (HFSE) such as Ti, Nb, and Ta. Zircon hosts Zr, Hf and some U, and apatite is the main host for P (e.g., Hermann 2002; Hermann and Rubatto 2009). Rutile preferentially incorporates Ta over Nb during hydration melting (Schmidt et al. 2004b; Xiong et al. 2011a), with Nb/Ta partition coefficients DNb/Ta < 1. In contrast, low-Mg amphibole, biotite, and phengite preferentially incorporate Nb over Ta during dehydration melting (Tiepolo et al. 2000; Green and Adam 2003; Stepanov and Hermann 2013), with Nb/Ta partition coefficients DNb/Ta > 1. Thus, subduction-zone fluids with elevated Nb/Ta ratios can form either by the breakdown of these hydrous minerals or by the presence of residual rutile in UHP eclogites. These results demonstrate that metamorphic dehydration and partial melting at the subarc depths may cause significant fractionation of trace elements with similar geochemical characteristics.

Because hydrous minerals host a wide range of trace elements, their presence and stability are a crucial factor in dictating the redistribution of elements during dehydration and melting at deep subduction zones. So are nominally anhydrous minor and accessory minerals. However, the stability of these minerals is highly influenced by temperature-pressure, fluid property, and fluid/rock ratio. As an accessory phase in the residue, for instance, monazite can be exhausted at elevated fluid/rock ratios at 800 to 900°C (Skora and Blundy 2010). Because the solubility of essential mineral structural components such as Ce in monazite increases exponentially with increasing temperature, only small amounts of anatectic melts are required to completely exhaust the accessory phase at temperatures >1,000°C (Stepanov et al. 2012). On the other hand, the dissolution of zircon into aqueous fluids can be significantly enhanced by the contemporaneous dissolution of Na-Al silicate components (Wilke et al. 2012). Therefore, the composition of subduction-zone fluids is dictated by the property of chemical reactions with passing rocks, which exerts substantial influence on the mobility of HFSE during subduction-zone metamorphism. Since supercritical fluids become available at UHP eclogite-facies conditions (Figure 1), the dissolution and transport of fluid-immobile incompatible trace elements are possible at the slab-mantle interface in the subduction channel (Zheng et al. 2011a).

Natural constraints

Due to the long journey from at least 100-km depth to the Earth’s surface, direct samples of deep subduction-zone fluids are not preserved in UHP metamorphic rocks. Nevertheless, metamorphic veins and migmatic leucosomes within UHP rocks can be used to retrieve information about the composition of deep fluids. Advanced micro-analytical methods are applied to acquire the geochemical composition of metamorphic and anatectic veins in UHP metamorphic terranes (Zheng et al. 2008; Chen et al., 2012a,2012b; Guo et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2012; Song et al. 2014). This leads to a better understanding of the role of fluids for mass transfer at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels. In addition, tiny MSI that are trapped within refractory minerals in UHP rocks may derive from anatectic melts (Ferrando et al. 2005; Malaspina et al. 2006; Gao et al. 2012, 2013; Liu et al. 2013), providing insights into the property and composition of deep subduction-zone fluids.

Metamorphic veins

Generally, there are two types of metamorphic veins in deeply subducted continental crust, which are mainly formed at subsolidus conditions: (1) felsic veins, which are primarily composed of variable abundances of felsic minerals such as quartz, feldspar, kyanite, and phengite with minor amounts of mafic minerals such as omphacite, garnet, zoisite, and amphibole (e.g., Franz et al. 2001; Li et al. 2001, Li et al. 2004; Zheng et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2012a; Sheng et al., 2012, 2013) and (2) mafic veins, which are usually composed of variable abundances of mafic minerals such as omphacite, epidote, zoisite, allanite, and garnet with minor amounts of felsic minerals such as quartz and kyanite (e.g., Gao et al. 2007; John et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2008; Spandler et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2012). In addition, the veins contain variable abundances of accessory minerals such as rutile, zircon, and apatite. Chemical reaction of the moving fluids with their host rocks scavenges various components into the fluids. This leads to different types of mineral parageneses for metamorphic veins in UHP metamorphic rocks. As a consequence, there is a significant variation in the composition of subduction-zone fluids, sometimes with survival of relict minerals from the fluid-scavenged rocks (e.g., Zheng et al. 2007; Sheng et al. 2012, 2013).

Available analyses on whole-rock geochemistry of metamorphic veins (Rubatto and Hermann 2003; Zhang et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2012a; Guo et al. 2012) provide evidence that many elements can be transported at least over short distances of a few meters. Because the formation of metamorphic veins is closely associated with the flow of aqueous solutions at subsolidus conditions, dissolution-reprecipitation reactions at appropriate fluid/rock ratios are necessary to produce various parageneses of vein-forming minerals. This is particularly so in view of the relatively low solubility of many major and trace elements in aqueous solutions (Figure 2), providing further evidence that dissolution-reprecipitation reactions are important for vein formation. Thus, the veins represent the material assemblages left behind from the passing fluid phase. As such, compositional data of metamorphic veins can be used to define the major element composition of metamorphic fluids by taking into account the solubility of vein minerals in aqueous solutions. Likewise, they can be used to approximate the trace element composition of metamorphic fluids by taking into account the partition coefficients between vein minerals and aqueous solutions.

Migmatic leucosomes and multiphase solid inclusions

In terms of their occurrence, composition, and age, migmatic leucosomes and MSI inside UHP metamorphic rocks can be inferred to represent the crystallized products of anatectic melts during continental collision, whereas restites are residues after partial melting and melt extraction. The majority of leucosomes and MSI have mineral parageneses similar to granitic rocks, suggesting their crystallization from felsic melts. Here, we refer the anatectic melts as the least evolved melts that are not completely separated from their parent rocks and thus experience the lowest extent of crystal fractionation (Li et al. 2013). In contrast, magmatic melts have evolved from different batches of anatectic melts, not only with complete separation from their parent rocks but also with significant crystal fractionation during their transport upward. Magmatic fluids are those exsolved from the magmatic melts during fractional crystallization at declined pressures. Studies of experimental petrology for dehydration melting of crustal rocks commonly produce melts with small ratios of melts to residued minerals. Such experimental melts are petrologically buffered by the multiphase assemblage of residued minerals under HP to UHP conditions. Therefore, they are petrologically more similar to the anatectic melts rather than the magmatic melts.

Geochemical analyses of migmatic leucosomes from UHP metamorphic terranes provide a proxy for the composition of anatectic melts (Zhang et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2012b; Yu et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013; Song et al. 2014). This is delineated by plotting the calc-alkalinity index (MALI = NaO + K2O - CaO in weight percentage) against SiO2 content (Figure 3a) and Si/Al ratios (molar SiO2/Al2O3) against (Na + K)/Al ratios [molar (Na2O + K2O)/Al2O3] (Figure 3b). For example, leucosomes inside UHP eclogites from North Qaidam (west-central China) exhibit large variations in composition (Chen et al. 2012b; Yu et al. 2012; Song et al. 2014), with SiO2 = 57.49 to 78.38 wt %, Al2O3 = 12.46 to 20.60 wt %, MALI = -3.22 to 5.86 and A/CNK = 0.68 to 1.26, Si/Al = 2.39 to 5.34, and (Na + K)/Al = 0.22 to 0.77 (Additional file 3: Table S2). Despite the variation from tonalitic to granodioritic to granitic, the composition of leucosomes is predominantly calcic (Figure 3a). The leucosomes exhibit significant enrichment of LILE and LREE but depletion of Nb, Ta, and HREE in the primitive mantle-normalized spidergrams (Figure 4). This generally resembles the distribution patterns of trace elements in common arc volcanics (Kelemen et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the leucosomes exhibit very large variations in trace element ratios, e.g., from 24 to 1,950 for Sr/Nd and from 0.21 to 25 for Th/U (Additional file 4: Table S3).

Composition of crystalline products of anatectic melts in UHP metamorphic terranes (Additional file3: Table S2). (a) MALI index (Na2O + K2O - CaO) against SiO2 contents, where the boundaries for calcic, calc-alkalic, alkali-calcic, and alkalic fields are after Frost et al. (2001). (b) Molar SiO2/Al2O3 ratios against molar (Na2O + K2O)/Al2O3 ratios, where open diamonds, stars, and circles denote the experimental data for aqueous solution, hydrous melt, and supercritical fluid, respectively, used in Figure two of Hermann et al. (2013) for comparison. Data for leucosomes in the UHP metamorphic rocks from North Qaidam are after Chen et al. (2012b), Yu et al. (2012), and Song et al. (2014), and those for multiphase solid inclusions (MSI) in garnet of the UHP eclogites from the Dabie orogen are after Gao et al. (2013). Large MSI have a size of 24 to 160 μm that were directly sampled by the internal ablation method for the LA-ICPMS analysis, whereas small MSI have a size of <24 μm that were sampled by the external ablation method with minor involvement of the host mineral (Gao et al. 2013).

Trace element spidergrams for migmatic leucosomes in the UHP metamorphic terrane of North Qaidam in China (Additional file4: Table S3). Black solid curves denote data from Dulan after Yu et al. (2012) and Song et al. (2014), and blue dash-dot curves denote data from Xitieshan after Chen et al. (2012b). Data for the primitive mantle are after McDonough and Sun (1995).

Restites provide complementary information to leucosomes on the composition of UHP melts. Garnet-rich rocks in the diamond-facies gneisses of the Kokchetav massif, Kazakhstan, display high MgO + FeO contents and depletion of SiO2 and alkalis. These restites formed at about 1,000°C and 5 GPa, have extreme depletion of LREE and Th, moderate depletion of LILE, enrichment of HREE, and highly variable Nb/Ta ratios, depending on whether residual phengite or residual rutile dominate the Nb/Ta in the restite (Stepanov et al. 2014). These data permit to constrain the composition of extracted melts as K-rich peraluminous granites with high LREE, strongly fractionated REE patterns, and moderate HREE and HFSE contents.

Some MSI are trapped in UHP minerals such as coesite, diamond, and majoritic garnet (Stöckhert et al. 2001; van Roermund et al. 2002; Scambelluri et al., 2008; Zhang et al. 2008), indicating that they were included as supercritical fluids at UHP conditions. Different sizes of felsic MSI in the garnet of UHP eclogites from the Dabie orogen (east-central China) exhibit very large variations in composition (Gao et al. 2013), with SiO2 = 63.78 to 94.43 wt %, Al2O3 = 1.89 to 18.26 wt %, MALI = 0.19 to 15.21, A/CNK = 0.18 to 1.54, Si/Al = 2.86 to 42.40, and (Na + K)/Al = 0.48 to 3.30 (Additional file 3: Table S2). While large MSI tend to exhibit high alkali contents, small MSI generally show high SiO2 contents. The elevated SiO2 contents but highly variable Al2O3 contents are attributable to the occurrence of almost single quartz phase in the MSI. This is particularly so for the small MSI that exhibit significantly higher Si/Al and (Na + K)/Al ratios than the experimentally defined fields for hydrous melts and supercritical fluids (Figure 3b), suggesting their precipitation from fluids rich in silica and alkalis. Trace element analyses of MSI in the garnet of Dabie eclogites show patterns with depletion of HFSE but more enrichment of LILE than LREE (Figure 5). These features are comparable with those observed in the partial melting experiments (Figure 2). Nevertheless, the MSI also exhibit very large variations in trace element ratios, e.g., from 0.37 to 1,333 for Sr/Nd and from 0.05 to 2.54 for Th/U (Additional file 4: Table S3). The formation of MSI in the garnet is attributed to dehydration melting due to phengite breakdown in the eclogites during exhumation (Gao et al. 2012, Gao et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013).

Trace element spidergrams for MS inclusions in garnet of UHP eclogite from the Dabie orogen, China (Additional file4: Table S3). (a) Large MS inclusions have a size of 24 to 160 μm that were directly sampled by internal ablation for the LA-ICPMS analysis. (b) Small MS inclusions have a size of <24 μm that were sampled by external ablation with minor involvement of the host mineral. Black curves denote the data from Gao et al. (2013), and blue curves denote the data from Liu et al. (2013). Data for the primitive mantle are after McDonough and Sun (1995). The composition of small MS inclusions was reconstructed by minimizing the Fe content of single MS inclusions relative to the host garnet in order to achieve the accurate estimate of its volume proportion relative to the ablated host garnet. This was based on the correct identification of mineral phases in these small MS inclusions.

Action of subduction-zone fluids

Accessary mineral records of trace element transport

Many field-based studies have indicated that the assumption of HFSE immobility in fluids is not always valid at subduction-zone metamorphic conditions. For example, Ti minerals such as titanite, rutile, and ilmenite in Alpine eclogitic veins are precipitated from metamorphic fluids (e.g., Philippot and Selverstone 1991), and metamorphic rutile is common in quartz-dominated veins hosted by UHP eclogites in Dabie-Sulu (Xiao et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2011b) and Chinese Tianshan (Gao et al. 2007; John et al. 2008). These observations suggest that metamorphic fluids can transport Ti at eclogite-facies conditions at least over short distances of a few meters. Combined with the generally low solubility of Ti in aqueous solutions (Figure 2), this indicates that dissolution-reprecipitation reactions must be involved in order to dissolve and transport the HFSE from host eclogites for rutile-bearing veining (Xia et al. 2010; Zheng et al. 2011a). While it is difficult to extract information about element solubilities from metamorphic and anatectic veins, important conclusions about trace element fractionation can be obtained from accessory minerals.

LA-ICPMS analyses of Nb and Ta concentrations in rutile are available for UHP eclogites and enclosed quartz veins from the Dabie-Sulu orogenic belt (Xiao et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2011b). In the case of large rutile grains, profile analyses yield consistently lower Nb/Ta ratios for internal domains than the continental crust, whereas marginal domains exhibit significant variations and elevations in Nb/Ta ratios (Figure 6a). In the other case of different sizes of rutile grains, the analyses give consistently higher Nb/Ta ratios than the continental crust (Figure 6b). In either case, the increase of Nb/Ta ratios is associated with the decrease of Ta contents, suggesting preferential incorporation of Nb over Ta into the metamorphic rutile. This is in agreement with the experimental observations showing that Ta is preferentially retained in the residue with respect to Nb during metamorphic dehydration and partial melting (Figure 2). In addition, the breakdown of hydrous minerals such as low-Mg amphibole, biotite, and phengite may have provided the high Nb/Ta fluids for rutile growth (Gao et al. 2014).

Plots of Nb/Ta ratios against Ta contents in rutile from UHP eclogite and enclosed quartz veins (Dabie-Sulu, China). (a) Large rutile grains in eclogite (#27a-1) and its enclosed quartz vein (#27b-1) from the Sulu orogen (data from Xiao et al. 2006). (b) Small rutile grains in eclogites and enclosed kyanite-quartz veins from the Sulu orogen (pair 1, data from Zhang et al. 2008) and the Dabie orogen (pair 2, data from Zheng et al. 2011b). Also shown are Nb/Ta ratios for the primitive mantle (McDonough and Sun 1995) and the continental crust (Rudnick and Gao 2003).

Zircon grains of metamorphic origin frequently occur in UHP eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks, exhibiting shapes and structures that indicate significant dissolution of protolith zircon and subsequent overgrowth of metamorphic zircon (e.g., Liati and Gebauer 1999; Rubatto and Hermann 2003; Zheng et al. 2004, 2007; Sheng et al. 2012, 2013). This indicates significant action of fluids on the protolith zircon at subsolidus to supersolidus conditions (Zheng, 2009). Dissolution of the protolith zircon becomes more efficient in supercritical fluids than in aqueous solutions and hydrous melts (Xia et al., 2010). This leads to metamorphic recrystallization of the protolith zircon via the mechanism of dissolution-reprecipitation (Figure 7). The resultant zircon domains commonly exhibit a porous texture in CL images, a consistent enrichment of trace elements such as LREE, HREE, and HFSE and nearly concordant U-Pb ages for the major UHP metamorphic episode. Substantially, zircon is an excellent phase to record the action of fluids because the U-Pb age, trace elements, and O and Hf isotopes can be determined within the same domain of single crystals (Chen et al. 2011; Sheng et al. 2012, 2013).

Trace element discrimination diagrams of metamorphosed zircons from UHP metamorphic rocks. The metamorphic recrystallization proceeds via the mechanisms of solid-state transformation (SST), replacement alteration (RA), and dissolution reprecipitation (DR), respectively. (a) Plot of (Yb/Gd)N versus (La/Sm)N, and (b) plot of Hf versus Nb + Ta. The zircon grains are from low-T/UHP metagranite in the Dabie orogen (Xia et al. 2010). The chondrite element values are after Sun and McDonough (1989).

During the subduction and exhumation of crustal rocks, the new growth of metamorphic and anatectic zircons generally depends on the availability of fluids (Zheng 2009; Xia et al. 2013). Likewise, the growth of metamorphic and anatectic garnets is primarily dictated by the breakdown of hydrous minerals such as amphibole, biotite, epidote, lawsonite, phengite, and zoisite at subsolidus and supersolidus conditions, respectively (e.g., Baxter and Caddick 2013; Li et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2014). All hydrous minerals are important hosts of given trace elements in HP to UHP metamorphic rocks, but with significant differences in trace element abundances. As a consequence, the newly grown zircon and garnet may acquire different concentrations of trace elements due to the breakdown of different hydrous minerals. So do the other minor and accessory minerals. Therefore, the stability of hydrous minerals at the subarc depths is a key not only to the metamorphic dehydration and partial melting but also to the partitioning of trace elements into the metamorphic and anatectic minerals.

Crust-mantle interaction in subduction channel

The mantle wedge above oceanic subduction channels usually belongs to the part of the asthenospheric mantle, which is hot (e.g., Stern 2002). In contrast, the mantle wedge above continental subduction channels commonly belongs to the part of the subcontinental lithospheric mantle (SCLM), which is cold (e.g., Zheng et al. 2013). This difference may be the reason why continental subduction zones generally have lower geotherms than the hot oceanic subduction zones. It is the low geotherms for HP blueschist- to eclogite-facies metamorphism (Figure 1) that results in the insignificant release of aqueous solutions during the subduction of crustal rocks at shallow depths of <80 km (Kerrick and Connolly 2001a, 2001b). As a consequence, there is insignificant loss of fluid-mobile incompatible trace elements from low-T/HP eclogites (Spandler et al. 2003, 2004; Miller et al. 2007; Xiao et al. 2012, 2013). In this regard, naturally exposed HP eclogite-facies rocks cannot serve as the target to investigate the fluid-assisted element mobility at subarc depths of 80 to 130 km, because they would be exhumed before attending the UHP metamorphic conditions (Agard et al. 2009). Instead, UHP eclogite-facies rocks are a sound target for this purpose. As such, the liberation of fluids at mantle depths of >80 km is a key to supra-subduction-channel (SSC) arc volcanism.

Dehydration of crustal rocks becomes prominent during their cold subduction to the subarc depths, where these rocks may be heated to 730 to 950°C at the slab-mantle interface (Hermann and Spandler 2008; Plank et al. 2009; Syracuse et al. 2010; Cooper et al. 2012). This also results in local dehydration melting, which is recorded by anatectic leucosomes, restites, and MSI in UHP metamorphic rocks (Zheng et al. 2011a; Gao et al. 2012, 2013; Chen et al. 2012b, 2013; Yu et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2013; Song et al. 2014; Stepanov et al. 2014). Fluids released from deeply subducting crustal rocks provide metasomatic agents for mass transfer at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels (Figure 8a). Reaction of the fluids with the mantle wedge peridotite generates metasomatic mantle domains (metasomes) that are responsible for the enrichment of fluid-mobile incompatible trace elements in arc volcanics (Zheng 2012; Spandler and Pirard 2013; Adam et al. 2014).

Schematic diagrams of the crust-mantle interaction in a continental subduction channel and the formation of SSC magmatic rocks. (a) The continental crust is subducted to mantle depths of >80 km, contributing incompatible major and trace elements to the SCLM wedge for crustal metasomatism. (b) Partial melting of the ultramafic to mafic metasomes and their underlying UHP crustal rocks yields mafic, intermediate, and felsic melts, respectively, for synexhumation and postcollisional magmatism. The difference in the composition of magmatic rocks is attributed to different extents of melt-peridotite reaction at the slab-mantle interface, where there is a jelly-sandwich structure in which a weak layer composed of metamorphic, anatectic and metasomatic rocks (the jelly) is sandwiched between the overlying mantle wedge and the underlying subducted crustal slab (Zheng et al. 2013).

Orogenic peridotites are common in many UHP terranes (Brueckner and Medaris 2000; Nimis and Morten 2000; Zhang et al. 2000), providing us with an excellent target to study the reaction of subduction-zone fluids with the mantle wedge at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels (Scambelluri et al. 2007; Zheng 2012). According to the occurrence of crustal derivatives in the orogenic peridotites, two types of crustal metasomatism may take place at mantle depths (Zheng 2012). One is modal metasomatism that is indicated by the presence of new mineral phases such as serpentine, chlorite, amphibole, phlogopite, apatite, carbonate, sulfide, titanite, ilmenite, and zircon, which are absent in primitive and depleted mantle sources. The metasomatic products may occur in serpentinized to chloritized peridotites or in pyroxenites and hornblendites. The new mineral phases are mineralogically and geochemically distinguishable from primary peridotite minerals. The other is cryptic metasomatism that is indicated by the absence of such new mineral phases but the enrichment of fluid-mobile incompatible trace elements such as LILE and LREE relative to HFSE and HREE. In the extreme case, only enrichment of highly incompatible water-soluble trace elements (e.g., LILE) occurs in orogenic peridotites, similar to the product of fluid metasomatism in forearc settings above oceanic subduction zones.

In association with variable occurrences of new mineral phases, variable enrichment of LILE and LREE in orogenic peridotites is prominent due to the crustal metasomatism (Brueckner et al. 2002; Malaspina et al. 2006, 2009; Scambelluri et al. 2006; Zhao et al. 2007b; Zhang et al. 2011). Both newly grown and relict zircon domains have been observed in orogenic peridotites (Katayama et al. 2003; Song et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2005, 2011; Hermann et al. 2006b; Zheng et al. 2006, 2008; Liati and Gebauer 2009; Xiong et al. 2011b). This indicates that both the chemical transport of dissolved Zr and the physical transport of crustal zircon xenocrysts by either metamorphic fluids or anatectic melts have taken place at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels (Zheng 2012). While U-Pb ages for the newly grown zircon directly date the metasomatic event, its Lu-Hf isotope composition is primarily inherited from the metasomatic agent and thus has little to do with the composition of the overlying lithosphere. The survival of protolith zircon in the orogenic peridotites suggests that the crustal metasomatism beneath the mantle wedge would have proceeded at kinetically limited conditions, and thus it did not achieve the thermodynamic equilibrium between crustal and mantle components.

Both aqueous solutions and hydrous melts are likely involved in the SSC metasomatism (Figure 8a). The former is commonly indicated by serpentinization and chloritization in orogenic peridotites, whereas the latter is generally recorded by pyroxenite and hornblendite in association with orogenic peridotite (Zheng 2012). The hydrous melts may originate from two types of continental crustal sources, one is the metagranite and other is the metasediment. Low-degree partial melting of the UHP crustal rocks yields alkaline igneous rocks of felsic composition (Zhao et al. 2012), and it is also a key to geochemical differentiation of subducted crustal rocks, because it can result in significant enrichment of melt-mobile incompatible trace elements relative to melt-immobile compatible trace elements in hydrous melts (McKenzie 1989). In contrast, high-degree partial melting of the deeply subducted continental crust gives rise to postcollisional granitoids (Zhao et al. 2007c).

Reaction of the mantle wedge peridotite with the felsic melts can create a variety of metasomatic rocks that range from mafic to ultramafic compositions, depending on the extent of melt-peridotite reaction in subduction channels (Zheng 2012). Olivine-poor metasomes may undergo partial melting upon heating, giving rise to various mafic igneous rocks in continental collision orogens (Zhao et al. 2013). Even andesitic melts could be produced by partial melting of a given mafic metasome that is generated by reaction of abundant felsic melts with the SSC peridotite (Chen et al. 2014). Therefore, various melts from basaltic to granitic compositions could be produced by partial melting of the metasomes in the mantle wedge and its underlying slab-mantle interface (Figure 8b). The crustal components in the metasomes can be identified in a series of diagrams plotting Ba/Th, Sr/Rb, (87Sr/86Sr)i, and ϵNd(t) values against (La/Yb)N values for mafic igneous rocks (Zhao et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2014). Similar diagrams are used to distinguish between metabasalt- and metasediment-derived melts in the SSC mantle source of continental basalts (Xu et al. 2014). These differ from oceanic arc basalts in which only the sediment-derived melt is isotopically inferred in their SSC mantle sources (e.g., Schiano et al. 1995; Elliott et al. 1997; Eiler et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2011).

Prospects for the future

Great advances have been made in the past two decades on the geochemistry of continental subduction-zone fluids. This is primarily achieved by natural observations of exhumed UHP eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks in collisional orogens in addition to experimental investigations of metamorphic dehydration and partial melting at subduction-zone P-T conditions. While metamorphic and anatectic veins in UHP rocks directly record mineral precipitation from these fluids, orogenic peridotites and pyroxenites provide an indirect record of transferring the crustal signal for various elements into the SCLM wedge. As such, continental deep subduction also delivers raw materials to the subduction factory. The crustal metasomatism at the slab-mantle interface in the subduction channel generates new mineral phases in orogenic peridotites, but it is critical to unambiguously distinguish between primary and secondary peridotite minerals. Therefore, we are still on the way to answer the following fundamental questions in subduction-zone processes: (1) How do mineral solubility and element partitioning change along the paths of subduction and exhumation at mantle depths of >80 km? (2) How do aqueous solutions, hydrous melts, and supercritical fluids respectively react with the mantle wedge peridotite to generate different composition of metasomes? (3) What is the role of subduction-zone fluids at the slab-mantle interface in dictating the composition of SSC mafic igneous rocks?

The property and behavior of deep subduction-zone fluids are substantial to the mass transfer at the slab-mantle interface in subduction channels. This is also a particularly important challenge because the fluids mediate the recycling of crustal components into the mantle and the reworking of the crust itself. Continental deep subduction triggers metamorphic dehydration and partial melting at the slab-mantle interface, but it did not create juvenile crust like arc volcanics above oceanic subduction zones. Nevertheless, partial melting of the SSC ultramafic metasomes gives rise to mafic igneous rocks in collisional orogens. The geochemical differentiation through dehydration melting and melt-peridotite reaction in continental subduction zones generally resembles that in oceanic subduction zones. However, this represents a different type of recycling of the continental crust compared to the more common recycling of terrigenous sediment in oceanic subduction zones. Partial melting of the continental SSC ultramafic metasomes also represents a different way of crustal growth and crust-mantle interaction with element fractionation from that in the much better studied case of arc volcanism above oceanic subduction zones. Therefore, it is of great significance to investigate comprehensively UHP metamorphic rocks and their associated assemblages such as ophiolites, peridotites, and pyroxenites in order to unravel the geochemical behavior of fluids and element recycling in the subduction factory.

References

Adam J, Locmelis M, Afonso JC, Rushmer T, Fiorentini ML: The capacity of hydrous fluids to transport and fractionate incompatible elements and metals within the Earth’s mantle. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2014, 15: 2241–2253. 10.1002/2013GC005199

Agard P, Yamato P, Jolivet L, Burov E: Exhumation of oceanic blueschists and eclogites in subduction zones: timing and mechanisms. Earth Sci Rev 2009, 92: 53–79. 10.1016/j.earscirev.2008.11.002

Baxter EF, Caddick MJ: Garnet growth as a proxy for progressive subduction zone dehydration. Geology 2013, 41: 643–646. 10.1130/G34004.1

Bebout GE: Metamorphic chemical geodynamics of subduction zones. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2007, 260: 373–393. 10.1016/j.epsl.2007.05.050

Bebout GE: Metasomatism in subduction zones of subducted oceanic slabs, mantle wedges, and the slab-mantle interface. In Metasomatism and the Chemical Transformation of Rock. Edited by: Harlov DE, Austrheim H. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2013:289–349.

Bebout GE: Chemical and isotopic cycling in subduction zones. Treatise Geochem 2014, 4: 703–747.

Brueckner HK, Medaris LG Jr: A general model for the intrusion and evolution of mantle peridotites in high-pressure and ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic terranes. J Metamorph Geol 2000, 18: 119–130.

Brueckner HK, Carswell DA, Griffin WL: Paleozoic diamonds within a Precambrian peridotite lens in UHP gneisses of the Norwegian Caledonides. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2002, 203: 805–816. 10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00919-6

Chen R-X, Zheng Y-F, Gong B, Zhao Z-F, Gao T-S, Chen B, Wu Y-B: Origin of retrograde fluid in ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks: constraints from mineral hydrogen isotope and water content changes in eclogite-gneiss transitions in the Sulu orogen. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2007, 71: 2299–2325. 10.1016/j.gca.2007.02.012

Chen R-X, Zheng Y-F, Gong B: Mineral hydrogen isotopes and water contents in ultrahigh-pressure metabasite and metagranite: constraints on fluid flow during continental subduction-zone metamorphism. Chem Geol 2011, 281: 103–124. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.12.002

Chen R-X, Zheng Y-F, Hu ZC: Episodic fluid action during exhumation of deeply subducted continental crust: geochemical constraints from zoisite-quartz vein and host metabasite in the Dabie orogen. Lithos 2012, 155: 146–166.

Chen D-L, Liu L, Sun Y, Sun W-D, Zhu X-H, Liu X-M, Guo C-L: Felsic veins within UHP eclogite at Xitieshan in North Qaidam, NW China: partial melting during exhumation. Lithos 2012, 136–139: 187–200.

Chen Y-X, Zheng Y-F, Hu ZC: Synexhumation anatexis of ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks: petrological evidence from granitic gneiss in the Sulu orogen. Lithos 2013, 156–159: 69–96.

Chen L, Zhao Z-F, Zheng Y-F: Origin of andesitic rocks: geochemical constraints from Mesozoic volcanics in the Luzong basin, South China. Lithos 2014, 190–191: 220–239.

Chopin C: Ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism; tracing continental crust into the mantle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2003, 212: 1–14. 10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00261-9

Cooper LB, Ruscitto DM, Plank T, Wallace PJ, Syracuse EM, Manning CE: Global variations in H2O/Ce: 1. Slab surface temperatures beneath volcanic arcs. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2012, 13(3):Q03024.

Eiler JM, Schiano P, Valley JW, Kita NT, Stolper EM: Oxygen-isotope and trace element constraints on the origins of silica-rich melts in the subarc mantle. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2007, 8: Q09012.

Elliott T, Plank T, Zindler A, White W, Bourdon B: Element transport from slab to volcanic front at the Mariana arc. J Geophys Res 1997, B102: 14991–15019.

Ferrando S, Frezzotti ML, Dallai L, Compagnoni R: Multiphase solid inclusions in UHP rocks (Su-Lu, China): remnants of supercritical silicate-rich aqueous fluids released during continental subduction. Chem Geol 2005, 223: 68–81. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.01.029

Franz L, Romer RL, Klemd R, Schmid R, Oberhansli R, Wagner T, Dong SW: Eclogite-facies quartz veins within metabasites of the Dabie Shan (eastern China): pressure-temperature-time-deformation path, composition of the fluid phase and fluid flow during exhumation of high-pressure rocks. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2001, 141: 322–346. 10.1007/s004100000233

Frezzotti ML, Ferrando S, Dallai L, Compagnoni R: Intermediate alkali-alumino- silicate aqueous solutions released by deeply subducted continental crust: fluid evolution in UHP OH-rich topaz-kyanite quartzites from Donghai (Sulu, China). J Petrol 2007, 48: 1219–1241. 10.1093/petrology/egm015

Frost BR, Barnes CG, Collins WJ, Arculus RJ, Ellis DJ, Frost CD: A geochemical classification for granitic rocks. J Petrol 2001, 42: 2033–2048. 10.1093/petrology/42.11.2033

Fu B, Touret JLR, Zheng Y-F, B-m J: Fluid inclusions in granulites, granulitized eclogites and garnet clinopyroxenites from the Dabie-Sulu terranes, eastern China. Lithos 2003, 70: 293–319. 10.1016/S0024-4937(03)00103-8

Gao J, John T, Klemd R, Xiong XM: Mobilization of Ti-Nb-Ta during subduction: evidence from rutile-bearing dehydration segregations and veins hosted in eclogite, Tianshan, NW China. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2007, 71: 4974–4996. 10.1016/j.gca.2007.07.027

Gao X-Y, Zheng Y-F, Chen Y-X: Dehydration melting of ultrahigh-pressure eclogite in the Dabie orogen: evidence from multiphase solid inclusions in garnet. J Metamorph Geol 2012, 30: 193–212. 10.1111/j.1525-1314.2011.00962.x

Gao X-Y, Zheng Y-F, Chen Y-X, Hu ZC: Trace element composition of continentally subducted slab-derived melt: insight from multiphase solid inclusions in ultrahigh-pressure eclogite in the Dabie orogen. J Metamorph Geol 2013, 31: 453–468. 10.1111/jmg.12029

Gao X-Y, Zheng Y-F, Xia X-P, Chen Y-X: U-Pb ages and trace elements of metamorphic rutile from ultrahigh-pressure quartzite in the Sulu orogen. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.04.032

Gong B, Chen R-X, Zheng Y-F: Water contents and hydrogen isotopes in nominally anhydrous minerals from UHP metamorphic rocks in the Dabie-Sulu orogenic belt. Chinese Sci Bull 2013, 58: 4384–4389. 10.1007/s11434-013-6069-7

Green TH, Adam J: Experimentally-determined trace element characteristics of aqueous fluid from dehydrated mafic oceanic crust at 3.0 GPa, 650–700°C. Eur J Mineral 2003, 15: 815–830. 10.1127/0935-1221/2003/0015-0815

Guo S, Ye K, Chen Y, Liu JB, Mao Q, Ma YG: Fluid-rock interaction and element mobilization in UHP metabasalt: constraints from an omphacite-epidote vein and host eclogites in the Dabie orogen. Lithos 2012, 136–139: 145–167.

Hack AC, Thompson AB, Aerts M: Phase relations involving hydrous silicate melts, aqueous fluids, and minerals. Rev Mineral Geochem 2007, 65: 129–185. 10.2138/rmg.2007.65.5

Hacker BR: H2O subduction beyond arcs. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2008, 9(3):Q03001. doi:10.1029/2007GC001707 doi:10.1029/2007GC001707

Hermann J: Allanite: thorium and light rare earth element carrier in subducted crust. Chem Geol 2002, 192: 289–306. 10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00222-X

Hermann J, Spandler C, Hack A, Korsakov AV: Aqueous fluids and hydrous melts in high-pressure and ultra-high pressure rocks: implications for element transfer in subduction zones. Lithos 2006, 92: 399–417. 10.1016/j.lithos.2006.03.055

Hermann J, Rubatto D, Trommsdorff V: Sub-solidus Oligocene zircon formation in garnet peridotite during fast decompression and fluid infiltration (Duria, Central Alps). Mineral Petrol 2006, 88: 181–206. 10.1007/s00710-006-0155-3

Hermann J, Spandler C: Sediment melts at subarc depths: an experimental study. J Petrol 2008, 49: 717–740.

Hermann J, Rubatto D: Accessory phase control on the trace element signature of sediment melts in subduction zones. Chem Geol 2009, 265: 512–526. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.05.018

Hermann J, Zheng Y-F, Rubatto D: Deep fluids in subducted continental crust. Elements 2013, 9: 281–288. 10.2113/gselements.9.4.281

Hermann J, Rubatto D: Subduction of continental crust to mantle depth: geochemistry of ultrahigh-pressure rocks. Treatise Geochem 2014, 4: 309–340.

Holtz F, Becker A, Freise M, Johannes W: The water-undersaturated and dry Qz-Ab-Or system revisited. Experimental results at very low water activities and geological implications. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2001, 141: 347–357. 10.1007/s004100100245

John T, Klemd R, Gao J, Garbe-Schönberg C-D: Trace-element mobilization in slabs due to non steady-state fluid-rock interaction: constraints from an eclogite-facies transport vein in blueschist (Tianshan, China). Lithos 2008, 103: 1–24. 10.1016/j.lithos.2007.09.005

Katayama I, Nakashima S: Hydroxyl in clinopyroxene from the deep subducted crust: evidence for H2O transport into the mantle. Am Mineral 2003, 88: 229–234.

Katayama I, Muko A, Iizuka T, Maruyama S, Terada K, Tsutsumi Y, Sano Y, Zhang RY, Liou JG: Dating of zircon from Ti-clinohumite-bearing garnet peridotite: implication for timing of mantle metasomatism. Geology 2003, 31: 713–716. 10.1130/G19525.1

Katayama I, Nakashima S, Yurimoto H: Water content in natural eclogite and implication for water transport into the deep upper mantle. Lithos 2006, 86: 245–259. 10.1016/j.lithos.2005.06.006

Kawamoto T, Kanzaki M, Mibe K, Matsukag KN, Ono S: Separation of supercritical slab-fluids to form aqueous fluid and melt components in subduction zone magmatism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012, 109: 18695–18700. 10.1073/pnas.1207687109

Kelemen PB, Hanghoj K, Greene AR: One view of the geochemistry of subduction-related magmatic arcs, with an emphasis on primitive andesite and lower crust. Treatise Geochem 2003, 3: 593–659.

Kerrick DM, Connolly JAD: Metamorphic devolatilization of subducted marine sediments and transport of volatiles to the Earth’s mantle. Nature 2001, 411: 293–296. 10.1038/35077056

Kerrick DM, Connolly JAD: Metamorphic devolatilization of subducted oceanic metabasalts: implications for seismicity, arc magmatism and volatile recycling. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2001, 189: 19–29. 10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00347-8

Klimm K, Blundy JD, Green TH: Trace element partitioning and accessory phase saturation during H2O-saturated melting of basalt with implications for subduction zone chemical fluxes. J Petrol 2008, 49: 523–553. 10.1093/petrology/egn001

Li Y-L, Zheng Y-F, Fu B, Zhou J-B, Wei C-S: Oxygen isotope composition of quartz-vein in ultrahigh-pressure eclogite from Dabieshan and implications for transport of high-pressure metamorphic fluid. Phys Chem Earth A 2001, 26: 695–704.

Li X-P, Zheng Y-F, Wu Y-B, Chen F-K, Gong B, Li Y-L: Low-T eclogite in the Dabie terrane of China: petrological and isotopic constraints on fluid activity and radiometric dating. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2004, 148: 443–470. 10.1007/s00410-004-0616-9

Li W-C, Chen R-X, Zheng Y-F, Li QL, Hu ZC: Zirconological tracing of transition between aqueous fluid and hydrous melt in the crust: constraints from pegmatite vein and host gneiss in the Sulu orogen. Lithos 2013, 162–163: 157–174.

Li W-C, Chen R-X, Zheng Y-F, Hu ZC: Dehydration and anatexis of UHP metagranite during continental collision in the Sulu orogen. J Metamorph Geol 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12100

Liati A, Gebauer D: Constraining prograde and retrograde P-T-t paths of Eocene HP rocks by SHRIMP dating of different zircon domains: inferred rates of heating, burial, cooling and exhumation for central Rhodope, northern Greece. Contrib Mineral Petrol 1999, 135: 340–354. 10.1007/s004100050516

Liati A, Gebauer D: Crustal origin of zircon in a garnet peridotite: a study of U-Pb SHRIMP dating, mineral inclusions and REE geochemistry (Erzgebirge, Bohemian Massif). Eur J Mineral 2009, 21: 737–750. 10.1127/0935-1221/2009/0021-1939

Liou JG, Ernst WG, Zhang RY, Tsujimori T, B-m J: Ultrahigh-pressure minerals and metamorphic terranes - the view from China. J Asian Earth Sci 2009, 35: 199–231. 10.1016/j.jseaes.2008.10.012

Liu Q, Hermann J, Zhang JF: Polyphase inclusions in the Shuanghe UHP eclogites formed by subsolidus transformation and incipient melting during exhumation of deeply subducted crust. Lithos 2013, 177: 91–1093.

Malaspina N, Hermann J, Scambelluri M, Compagnoni R: Polyphase inclusions in garnet-orthopyroxenite (Dabie Shan, China) as monitors for metasomatism and fluid-related trace element transfer in subduction zone peridotite. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2006, 249: 173–187. 10.1016/j.epsl.2006.07.017

Malaspina N, Hermann J, Scambelluri M: Fluid/mineral interaction in UHP garnet peridotite. Lithos 2009, 107: 38–52. 10.1016/j.lithos.2008.07.006

Manning CE: The chemistry of subduction-zone fluids. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2004, 223: 1–16. 10.1016/j.epsl.2004.04.030

McDonough WF, Sun S-s: The composition of the Earth. Chem Geol 1995, 120: 223–253. 10.1016/0009-2541(94)00140-4

McKenzie D: Some remarks on the movement of small melt fractions in the mantle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1989, 95: 53–72. 10.1016/0012-821X(89)90167-2

Meng DW, Wu XL, Fan XY, Meng X, Zheng JP, Mason R: Submicron-sized fluid inclusions and distribution of hydrous components in jadeite, quartz and symplectite-forming minerals from UHP jadeite-quartzite in the Dabie Mountains. China: TEM and FTIR Invest Appl Geochem 2009, 24: 517–526.

Mibe K, Kawamoto T, Matsukage KN, Fei YW, Ono S: Slab melting versus slab dehydration in subduction-zone magmatism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2011, 108: 8177–8182. 10.1073/pnas.1010968108

Miller C, Zanetti A, Thöni M: Eclogitisation of gabbroic rocks: redistribution of trace elements and Zr in rutile thermometry in an Eo-Alpine subduction zone (Eastern Alps). Chem Geol 2007, 239: 96–123. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2007.01.001

Mukherjee BK, Sachan HK: Fluids in coesite-bearing rocks of the Tso Morari Complex, NW Himalaya: evidence for entrapment during peak metamorphism and subsequent uplift. Geol Mag 2009, 146: 876–889. 10.1017/S0016756809990069

Ni P, Zhu X, Wang RC, Shen K, Zhang ZM, Qiu JS, Huang JP: Constraining ultrahigh-pressure (UHP) metamorphism and titanium ore formation from an infrared microthermometric study of fluid inclusions in rutile from Donghai UHP eclogites, eastern China. Geol Soc Am Bull 2008, 120: 1296–1304. 10.1130/B26090.1

Nimis P, Morten L: P–T evolution of ‘crustal’ garnet peridotites and included pyroxenites from Nonsberg area (upper Austroalpine), NE Italy: from the wedge to the slab. J Geodyn 2000, 30: 93–115. 10.1016/S0264-3707(99)00029-0

Peacock SM, Wang K: Seismic consequences of warm versus cool subduction metamorphism: examples from southwest and northeast Japan. Science 1999, 286: 937–939. 10.1126/science.286.5441.937

Pearson DG, Brenker FE, Nestola F, McNeill J, Nasdala L, Hutchison MT, Matveev S, Mather K, Silversmit G, Schmitz S, Vekemans B, Vincze L: Hydrous mantle transition zone indicated by ringwoodite included within diamond. Nature 2014, 507: 221–224. 10.1038/nature13080

Philippot P, Selverstone J: Trace-element-rich brines in eclogitic veins: implications for fluid composition and transport during subduction. Contrib Mineral Petrol 1991, 106: 417–430. 10.1007/BF00321985

Plank T, Cooper LB, Manning CE: Emerging geothermometers for estimating slab surface temperatures. Nat Geosci 2009, 2: 611–615. 10.1038/ngeo614

Rubatto D, Hermann J: Zircon formation during fluid circulation in eclogites (Monviso, Western Alps): implications for Zr and Hf budget in subduction zones. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2003, 67: 2173–2187. 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)01321-2

Rudnick RL, Gao S: Composition of the continental crust. Treatise Geochem 2003, 3: 1–64.

Rumble D, Liou JG, B-m J: Continental crust subduction and ultrahigh pressure metamorphism. Treatise Geochem 2003, 3: 293–319.

Rupke LH, Morgan JP, Hort M, Connolly JAD: Serpentine and the subduction zone water cycle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2004, 223: 17–34. 10.1016/j.epsl.2004.04.018

Scambelluri M, Hermann J, Morten L, Rampone E: Melt- versus fluid-induced metasomatism in spinel to garnet wedge peridotites (Ulten Zone, Eastern Italian Alps): clues from trace element and Li abundances. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2006, 151: 371–394. 10.1007/s00410-006-0078-3

Scambelluri M, Malaspina N, Hermann J: Subduction fluids and their interaction with the mantle wedge: a perspective from the study of high-pressure ultramafic rocks. Per Mineral 2007, 76: 253–265.

Scambelluri M, Pettke T, Van Roermund HLM: Majoritic garnets monitor deep subduction fluid flow and mantle dynamics. Geology 2008, 36: 59–62. 10.1130/G24056A.1

Schertl H-P, O’Brien PJ: Continental crust at mantle depths: key minerals and microstructures. Elements 2013, 9: 261–266. 10.2113/gselements.9.4.261

Schiano P, Clocchiatti R, Shimizu N, Maury RC, Jochum KP, Hofmann AW: Hydrous, silica-rich melts in the sub-arc mantle and their relationship with erupted arc lavas. Nature 1995, 377: 595–600. 10.1038/377595a0

Schmidt MW, Poli S: Experimentally based water budgets for dehydrating slabs and consequences for arc magma generation. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1998, 163: 361–379. 10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00142-3

Schmidt MW, Poli S: Generation of mobile components during subduction of oceanic crust. Treatise Geochem 2003, 3: 567–591.

Schmidt MW, Vielzeuf D, Auzanneau E: Melting and dissolution of subducting crust at high pressures: the key role of white mica. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2004, 228: 65–84. 10.1016/j.epsl.2004.09.020

Schmidt MW, Dardon A, Chazot G, Vannucci R: The dependence of Nb and Ta rutile-melt partitioning on melt composition and Nb/Ta fractionation during subduction processes. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2004, 226: 415–432. 10.1016/j.epsl.2004.08.010

Seaman SJ, Williams ML, Jercinovic MJ, Koteas GC, Brown LB: Water in nominally anhydrous minerals: Implications for partial melting and strain localization in the lower crust. Geology 2013, 41: 1051–1054. 10.1130/G34435.1

Sheng YM, Xia QK, Yang XZ, Hao YT: H2O contents and D/H ratios of nominally anhydrous minerals from ultrahigh-pressure eclogites of the Dabie orogen, eastern China. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2007, 71: 2079–2103. 10.1016/j.gca.2007.01.018

Sheng Y-M, Zheng Y-F, Chen R-X, Li QL, Dai MN: Fluid action on zircon growth and recrystallization during quartz veining within UHP eclogite: Insights from U-Pb ages, O-Hf isotopes and trace elements. Lithos 2012, 136–139: 126–144.

Sheng Y-M, Zheng Y-F, Li S-N, Hu ZC: Element mobility during continental collision: insights from polymineralic metamorphic vein within UHP eclogite in the Dabie orogen. J Metamorph Geol 2013, 31: 221–241. 10.1111/jmg.12016

Skora S, Blundy J: High-pressure hydrous phase relations of radiolarian clay and implications for the involvement of subducted sediment in arc magmatism. J Petrol 2010, 51: 2211–2243. 10.1093/petrology/egq054

Skora S, Blundy J: Monazite solubility in hydrous silicic melts at high pressure conditions relevant to subduction zone metamorphism. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2012, 321–322: 104–114.

Song SG, Zhang LF, Niu YL, Su L, Jian P, Liu DY: Geochronology of diamond-bearing zircons from garnet peridotite in the North Qaidam UHPM belt. Northern Tibetan Plateau: a record of complex histories from oceanic lithosphere subduction to continental collision. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2005, 234: 99–118. 10.1016/j.epsl.2005.02.036

Song SG, Niu YL, Su L, Wei CJ, Zhang LF: Adakitic (tonalitic-trondhjemitic) magmas resulting from eclogite decompression and dehydration melting during exhumation in response to continental collision. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2014, 130: 42–62.

Spandler CJ, Hermann J, Arculus RJ, Mavrogenes JA: Redistribution of trace elements during prograde metamorphism from lawsonite blueschist to eclogite facies; implications for deep subduction-zone processes. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2003, 146: 205–222. 10.1007/s00410-003-0495-5

Spandler C, Hermann J, Arculus R, Mavrogenes J: Geochemical heterogeneity and element mobility in deeply subducted oceanic crust: insights from high-pressure mafic rocks from New Caledonia. Chem Geol 2004, 206: 21–42. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.01.006

Spandler C, Mavrogenes J, Hermann J: Experimental constraints on element mobility from subducted sediments using high-P synthetic fluid/melt inclusions. Chem Geol 2007, 239: 228–249. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.10.005

Spandler C, Pettke T, Rubatto D: Internal and external fluid sources for eclogite-facies veins in the Monviso meta-ophiolite, Western Alps: implications for fluid flow in subduction zones. J Petrol 2011, 52: 1207–1236. 10.1093/petrology/egr025

Spandler C, Pirard C: Element recycling from subducting slabs to arc crust: a review. Lithos 2013, 170–171: 208–223.

Stepanov AS, Hermann J, Rubatto D, Rapp RP: Experimental study of monazite/melt partitioning with implications for the REE, Th and U geochemistry of crustal rocks. Chem Geol 2012, 300–301: 200–220.

Stepanov AS, Hermann J: Fractionation of Nb and Ta by biotite and phengite: Implications for the “missing Nb paradox”. Geology 2013, 41: 303–306. 10.1130/G33781.1

Stepanov AS, Hermann J, Korsakov AV, Rubatto D: Geochemistry of ultrahigh-pressure anatexis: fractionation of elements in the Kokchetav gneisses during melting at diamond-facies conditions. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2014, 167: 1002.

Stern RJ: Subduction zones Rev Geophys. 2002, 40(4):1012. doi:10.1029/2001RG000108 doi:10.1029/2001RG000108

Stöckhert B, Duyster J, Trepman C, Massonne H-J: Microdiamond daughter crystals precipitated from supercritical COH + silicate fluids included in garnet, Erzgebirge, Germany. Geology 2001, 29: 391–394. 10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0391:MDCPFS>2.0.CO;2

Su W, You ZD, Cong BL: Cluster of water molecules in garnet from ultrahigh-pressure eclogite. Geology 2002, 30: 611–614. 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0611:COWMIG>2.0.CO;2

Sun S-s, McDonough WF: Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalt: implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol Soc Spec Publ 1989, 42: 313–345. 10.1144/GSL.SP.1989.042.01.19

Syracuse EM, van Keken PE, Abers GA: The global range of subduction zone thermal models. Phys Earth Planet Inter 2010, 183: 73–90. 10.1016/j.pepi.2010.02.004

Tatsumi Y, Eggins S: Subduction Zone Magmatism. Blackwell Science, Oxford; 1995. 211 pp 211 pp

Tiepolo M, Vannucci R, Oberti R, Foley S, Bottazzi P, Zanetti A: Nb and Ta incorporation and fractionation in titanian pargasite and kaersutite: crystal-chemical constraints and implications for natural systems. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2000, 176: 185–201. 10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00004-2

Turner S, Caulfield J, Turner M, van Keken P, Maury R, Sandiford M, Prouteau G: Recent contribution of sediments and fluids to the mantle’s volatile budget. Nature Geosci 2011, 5: 50–54. 10.1038/ngeo1325

van Roermund HLM, Carswell DA, Drury MR, Heijboert TC: Microdiamonds in a megacrystic garnet websterite pod from Bardane on the island of Fjortoft, western Norway: evidence for diamond formation in mantle rocks during deep continental subduction. Geology 2002, 30: 959–962. 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0959:MIAMGW>2.0.CO;2

Wilke M, Schmidt C, Dubrail J, Appel K, Borchert M, Kvashnina K, Manning CE: Zircon solubility and zirconium complexation in H2O + Na2O + SiO2 ± Al2O3 fluids at high pressure and temperature. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2012, 349–350: 15–25.

Wu Y-B, Gao S, Zhang H-F, Yang S-H, Liu X-C, Jiao W-F, Liu Y-S, Yuan H-L, Gong H-J, He M-C: U-Pb age, trace-element, and Hf-isotope compositions of zircon in a quartz vein from eclogite in the western Dabie Mountains: constraints on fluid flow during early exhumation of ultra high-pressure rocks. Am Mineral 2009, 94: 303–312. 10.2138/am.2009.3042

Xia QK, Sheng YM, Yang XZ, Yu HM: Heterogeneity of water in garnets from UHP eclogites, eastern Dabieshan. China Chem Geol 2005, 224: 237–246. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.08.003

Xia Q-X, Zheng Y-F, Hu Z-C: Trace elements in zircon and coexisting minerals from low-T/UHP metagranite in the Dabie orogen: implications for fluid regime during continental subduction-zone metamorphism. Lithos 2010, 114: 385–413. 10.1016/j.lithos.2009.09.013

Xia Q-X, Zheng Y-F, Chen Y-X: Protolith control on fluid availability for zircon growth during continental subduction-zone metamorphism in the Dabie orogen. J Asian Earth Sci 2013, 67–68: 93–113.

Xiao YL, Hoefs J, van den Kerkhof AM, Simon K, Fiebig J, Zheng Y-F: Fluid evolution during HP and UHP metamorphism in Dabie Shan, China: constraints from mineral chemistry, fluid inclusions and stable isotopes. J Petrol 2002, 43: 1505–1527. 10.1093/petrology/43.8.1505

Xiao YL, Sun WD, Hoefs J, Simon K, Zhang ZM, Li SG, Hofmann AW: Making continental crust through slab melting: constraints from niobium-tantalum fractionation in UHP metamorphic rutile. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2006, 70: 4770–4782. 10.1016/j.gca.2006.07.010

Xiao YY, Lavis S, Niu YL, Pearce JA, Li HK, Wang HC, Davidson J: Trace-element transport during subduction-zone ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism: evidence from western Tianshan. China Geol Soc Am Bull 2012, 124: 1113–1129. 10.1130/B30523.1

Xiao YY, Niu YL, Song SG, Davidson J, Liu XM: Elemental responses to subduction-zone metamorphism: constraints from the North Qilian Mountain, NW China. Lithos 2013, 160–161: 55–67.

Xiong XL, Keppler H, Audetat A, Ni HW, Sun WD, Li Y: Partitioning of Nb and Ta between rutile and felsic melt and the fractionation of Nb/Ta during partial melting of hydrous metabasalt. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2011, 75: 1673–1692. 10.1016/j.gca.2010.06.039

Xiong Q, Zheng JP, Griffin WL, O’Reilly SY, Zhao JH: Zircons in the Shenglikou ultrahigh-pressure garnet peridotite massif and its country rocks from the North Qaidam terrane (western China): Meso-Neoproterozoic crust-mantle coupling and early Paleozoic convergent plate-margin processes. Precambr Res 2011, 187: 33–57. 10.1016/j.precamres.2011.02.003

Xu Z, Zheng Y-F, He H-Y, Zhao Z-F: Phenocryst He-Ar isotopic and whole-rock geochemical constraints on the origin of crustal components in the mantle source of Cenozoic continental basalt in eastern China. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 2014, 272: 99–110.

Yu SY, Zhang JX, Real PGD: Geochemistry and zircon U/Pb ages of adakitic rocks from the Dulan area of the North Qaidam UHP terrane, north Tibet: constraints on the timing and nature of regional tectonothermal events. Gondwana Res 2012, 21: 167–179. 10.1016/j.gr.2011.07.024

Zhang RY, Liou JG, Yang JS, Yui T-F: Petrochemical constraints for dual origin of garnet peridotites from the Dabie–Sulu UHP terrane, eastern-central China. J Metamorph Geol 2000, 18: 149–166. 10.1046/j.1525-1314.2000.00248.x

Zhang JF, Green HW, Bozhilov K, Jin ZM: Faulting induced by precipitation of water at grain boundaries in hot subducting oceanic crust. Nature 2004, 428: 633–636. 10.1038/nature02475

Zhang RY, Yang JS, Wooden JL, Liou JG, Li TF: U-Pb SHRIMP geochronology of zircon in garnet peridotite from the Sulu UHP terrane, China: implication for mantle metasomatism and subduction-zone UHP metamorphism. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2005, 237: 729–734. 10.1016/j.epsl.2005.07.003

Zhang ZM, Shen K, Sun WD, Liu YS, Liou JG, Shi C, Wang JL: Fluids in deeply subducted continental crust: petrology, mineral chemistry and fluid inclusion of UHP metamorphic veins from the Sulu orogen, eastern China. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2008, 72: 3200–3228. 10.1016/j.gca.2008.04.014

Zhang ZM, Dong X, Liou JG, Liu F, Wang W, Yui F: Metasomatism of garnet peridotite from Jiangzhuang, southern Sulu UHP belt: constraints on the interactions between crust and mantle rocks during subduction of continental lithosphere. J Metamorph Geol 2011, 29: 917–937. 10.1111/j.1525-1314.2011.00947.x

Zhao Z-F, Chen B, Zheng Y-F, Chen R-X, Wu Y-B: Mineral oxygen isotope and hydroxyl content changes in ultrahigh-pressure eclogite-gneiss transition from the Chinese Continental Scientific Drilling core samples. J Metamorph Geol 2007, 25: 165–186. 10.1111/j.1525-1314.2007.00693.x

Zhao R, Zhang RY, Liou JG, Booth AL, Pope EC, Chamberlain C: Petrochemistry, oxygen isotopes and U-Pb SHRIMP geochronology of mafic–ultramafic bodies from the Sulu UHP terrane. China J Metamorph Geol 2007, 25: 207–224. 10.1111/j.1525-1314.2007.00691.x

Zhao Z-F, Zheng Y-F, Wei C-S, Wu Y-B: Post-collisional granitoids from the Dabie orogen in China: Zircon U-Pb age, element and O isotope evidence for recycling of subducted continental crust. Lithos 2007, 93: 248–272. 10.1016/j.lithos.2006.03.067

Zhao Z-F, Zheng Y-F, Zhang J, Dai LQ, Liu XM: Syn-exhumation magmatism during continental collision: evidence from alkaline intrusives of Triassic age in the Sulu orogen. Chem Geol 2012, 328: 70–88.

Zhao Z-F, Dai L-Q, Zheng Y-F: Postcollisional mafic igneous rocks record crust-mantle interaction during continental deep subduction. Sci Rep 2013, 3: 3413. doi:10.1038/srep03413 doi:10.1038/srep03413

Zheng Y-F, Fu B, Gong B, Li L: Stable isotope geochemistry of ultrahigh pressure metamorphic rocks from the Dabie-Sulu orogen in China: implications for geodynamics and fluid regime. Earth Sci Rev 2003, 62: 105–161. 10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00133-2

Zheng Y-F, Wu Y-B, Chen FK, Gong B, Li L, Zhao Z-F: Zircon U-Pb and oxygen isotope evidence for a large-scale 18O depletion event in igneous rocks during the Neoproterozoic. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2004, 68: 4145–4165. 10.1016/j.gca.2004.01.007

Zheng JP, Griffin WL, O’Reilly SY, Yang JS, Zhang RY: A refractory mantle protolith in younger continental crust, east-central China: age and composition of zircon in the Sulu ultrahigh-pressure peridotite. Geology 2006, 34: 705–708. 10.1130/G22569.1