Abstract

Background

Fathers are intricately bound up in all aspects of family life. This review examines fathers in the presence of HIV: from desire for a child, through conception issues, to a summary of the knowledge base on fathers within families affected by HIV.

Methods

A mixed-methods approach is used, given the scarcity of literature. A review is provided on paternal and male factors in relation to the desire for a child, HIV testing in pregnancy, fatherhood and conception, fatherhood and drug use, paternal support and disengagement, fatherhood and men who have sex with men (MSM), and paternal effects on child development in the presence of HIV. Literature-based reviews and systematic review techniques are used to access available data Primary data are reported on the issue of parenting for men who have sex with men.

Results

Men with HIV desire fatherhood. This is established in studies from numerous countries, although fatherhood desires may be lower for HIV-positive men than HIV-negative men. Couples do not always agree, and in some studies, male desires for a child are greater than those of their female partners. Despite reduced fertility, support and services, many proceed to parenting, whether in seroconcordant or serodiscordant relationships. There is growing knowledge about fertility options to reduce transmission risk to uninfected partners and to offspring.

Within the HIV field, there is limited research on fathering and fatherhood desires in a number of difficult-to-reach groups. There are, however, specific considerations for men who have sex with men and those affected by drug use. Conception in the presence of HIV needs to be managed and informed to reduce the risk of infection to partners and children. Further, paternal support plays a role in maternal management.

Conclusions

Strategies to improve HIV testing of fathers are needed. Paternal death has a negative impact on child development and paternal survival is protective. It is important to understand fathers and fathering and to approach childbirth from a family perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fathers are intricately bound up in all aspects of family life. Family issues play a part in determining life roles, goals and social environment [1]. Yet within the HIV field, fatherhood is understudied. This is a shortcoming, given that HIV itself is predominantly a sexually transmitted infection, closely intertwined with human reproduction and intimate relationships. As fathers have input over the life course, from conception and birth attendance to child rearing, parenting and grand-parenting, their absence in the literature is stark.

This paper discusses a variety of fathering issues in the presence of HIV infection. Motherhood and parenting are empty concepts if fathers are not consulted, and any sociological or psychological study of families will confirm the central roles that relationships and fathers play. The paper should be read in conjunction with the paper by Hosegood and Madhavan [2] in this Journal of the International AIDS Society supplement, which may provide some explanatory pathways for the absence of data on fathers and the underrepresentation of paternal insights and views within the literature.

Methods

The review focuses on seven topics, which, although not exhaustive, provides a synthesis of the existing literature. This takes the form of systematic reviews when there is a sufficient body of data and original empirical data.

The topic, desire for a child, is covered by summarizing the current literature on desire for a child and conducting a specific systematic search on studies looking at childhood desires among men. The coverage was based on a previous systematic review [3] updated and adjusted to focus on men using Pubmed, the Cochrane Database and Psychlit. The search used the key terms, "fertility desire", "pregnancy", "reproductive decision making", "reproductive intentions", "motherhood", "fatherhood", "fathers", "men", "males" and "parenthood". Papers were then restricted to those which included mention of HIV and AIDS.

The topics of HIV testing in pregnancy, fatherhood and conception, fatherhood and drug use, paternal support and disengagement were summarized and reviewed based on a synthesis of published literature. For these topics, the paucity of data rendered a systematic review inappropriate.

The topic, fatherhood and men who have sex with men (MSM), was reviewed based on a synthesis of published literature and supplemented by original data from a survey of male HIV clinic attendees. This information was gathered in the UK [4]. The published data from this study focused on heterosexual, HIV-positive men (n = 32). For the purpose of this report, the data from 84 men who self-reported their sexuality as MSM" were included.

Questionnaire responses were gathered from consecutive male attendees at a London HIV clinic (n = 168) in a study approved by the local ethics committee. One hundred and sixteen men agreed to participate (69.1% response rate). Of these, 84 (72.4%) self-reported their sexuality as MSM signed an informed consent form, were provided with information as to the purpose of the study, assured of anonymity and completed a detailed 17-item questionnaire. The questionnaire included an examination of background demographic issues, parenting experience, attitudes toward parenthood, information needs in relation to reproductive support and service provision, decision making and possibility of unprotected sex, and the meaning of fatherhood.

Questions were rated on Lickert-type or forced choice scales, derived from scales previously utilized in a study of maternal attitudes to parenting in the presence of HIV infection. The data was analysed using SPSS

The section, Fatherhood and child development, was based on the findings from the Joint Learning Initiative on Children and AIDS report [5]. A systematic review of child outcome, orphaning and HIV formed the basis of this report. Data on paternal death were extracted for this article.

Results

Desire for a child

For men, fertility, status and lineage considerations all contribute to fertility desires. Most men reside in prenatal societies. Antle et al [1] described the importance that parenting has to people living with HIV, who saw it as a joyous part of their lives. In a large US representative sample of HIV-positive males, 28-29% desired children in the future [6].

A systematic review [3] of pregnancy desires identified 29 studies exploring reproductive intentions among HIV positive groups of people internationally. Twenty were studies of women only, seven explored views of men and women, and two examined the views of men exclusively.

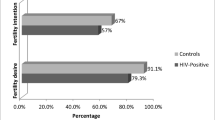

Data on men who have sex with men and bisexual men are particularly elusive. Indeed, some studies on parenting desires conducted among HIV populations specifically exclude men who e have sex only with men [6, 7]. Men continue to desire fatherhood in the presence of HIV, whether from the United Kingdom [4], South Africa [8, 9], Brazil [10, 11] or Uganda [12]. In one study in Uganda, men were more likely than women to desire children in the presence of HIV [13]. This was confirmed in a study in Nigeria [14], which also showed a desire for multiple children by men who were newly diagnosed and who had not disclosed their status. A USA study of 2864 people living with HIV showed that 59% of males expected to have a child in the future, but 20% of their female partners were not in agreement [6].

Yet when men and women with HIV are compared to HIV-negative groups, relatively lower fertility desires are reported. A study in Uganda showed a six-fold decrease in desire for children in the presence of HIV [12].

A systematic review of the terms, "pregnancy intentions in HIV" and "males/men", was carried out. The term, "pregnancy intentions", generated 1 122 studies, but when combined with HIV, this reduced to 66. When combined with "men and/or male", 28 studies remained. Hand sorting to meet inclusion criteria (male data, quantitative or qualitative methodology, pregnancy intention outcomes) revealed 14 relevant studies, 10 quantitative and four qualitative. These studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 shows consistent reports of a desire for fatherhood, with one qualitative study noting that none had "extinguished" the desire for a child. Despite this desire, many studies report a lack of information, services, advice and support.

HIV testing in pregnancy

HIV testing in pregnancy has become a standard facility available within pregnancy care. Yet, historically, this has been focused on women, with few attempts to include partners, despite the fact that it is highly cost-effective to offer screening to male partners [16] to record discordancy and to reduce the possibility of transmission of HIV during pregnancy. Late HIV infection during pregnancy may result in undetected HIV, missed opportunities for antiretroviral treatment and an elevated chance of vertical transmission. Policy has been very slow to change, despite the fact that testing women only is counterproductive, enhances stigma and leaves men out of the cycle of medical care [17].

Studies on couples testing show this approach to be viable. It results in reduced stigma, enhanced treatment uptake and reduced risk exposure in the event of discordancy [18–20]. Male partner testing is increased when women attending antenatal clinics are requested to invite their partners to attend [21, 22]. Couple counseling has shown greater levels of disclosure and acceptance [21, 22]. Women are more willing to accept HIV testing in pregnancy if their partners are tested at the same time [23] or even simply attend the clinic with them [24]. The converse is also true in that fear of negative responses from male partners is a disincentive to women testing [25, 26]. Yet randomized, controlled trials show low uptake of couples testing, and innovation is needed to reach out more systematically to men [27].

It is also curious to note that HIV testing has been confined to antenatal care with no parallel provision in family planning [28], termination of pregnancy clinics [29] or well-men (or women) clinics. This probably reflects a focus on the infant and may be short sighted. Provision for men at multiple venues may be a more effective strategy.

Fatherhood and conception

Conceiving a baby is an issue of heightened concern in the presence of HIV. The advent of new therapies and the growing knowledge base has meant that parenting in the presence of HIV is a realistic option [30, 31]. Attainment of fatherhood in the presence of HIV is affected by discordancy and by which partner is HIV positive. Interventions concentrate on reduction of viral load, which in turn reduces (but does not eliminate) risk of infection.

The key considerations relate to the risk of infection at the point of conception, reduced fertility as a result of HIV infection, prevention of infection to the infant, and access to support and services in the process of conception and pregnancy. Fertility care and treatment is well established as an HIV-associated service need. In 2001, 75% of fertility clinics surveyed in the UK had a policy of offering treatment to HIV-positive couples [32].

Reduced fertility and problems in conception have been reported in many couples who wish to have a baby, but who do not want to expose an uninfected partner to HIV [33]. Reduced motility of sperm has been noted in the presence of antiretroviral treatment [34, 35]. Treatment access is often limited, with ethical and referral barriers reported. Infertility problems were confirmed in a Spanish study [36] with abnormal semen parameters in 83.4% of HIV-infected and 41.7% of HIV-uninfected partners of 130 HIV-positive women. In an African study, there was a high level of risk exposure for non-infected male partners of HIV-positive women desiring pregnancy [37].

Where the man is HIV positive, conception has been documented in the presence of semen washing and in timed unprotected sex. For HIV-positive men, there are four options [38]. Three remove the possibility of genetic parenting: donor sperm insemination (which reduces the risk of viral transmission), fostering and adoption. Sperm-washing techniques have been well described for a number of years and are based on the finding that HIV does not attach to live sperm [39–44]. The techniques require high-level technological provision and have been well established as effective, with minimal risks of infection to either the infant or the partner [45–47, 30].

Strategies for harm reduction for couples with no access to treatment [49] try to limit exposure of the uninfected partner. The risk of transmission from an HIV-positive man to an HIV-negative woman in studies in the West is quoted as 0.1-0.3% per act of intercourse [49–51]. This may be elevated in the presence of coinfections. The risk of transmission from an HIV-positive woman to an uninfected man is somewhat lower.

Antiretroviral treatment may affect semen viral load. A review of 19 studies concluded that undetectable viral load in semen was possible with effective treatment, and was negatively influenced by poor adherence to treatment and the presence of other sexually transmitted infections [52]. Caution is consistently needed as studies have also established definitive viral shedding, even in the presence of full viral suppression [53–55]. A number of studies have attempted to evaluate the risk of infection to partners when conception is attempted. This varies by viral load, condom use outside of the fertility window and treatment status of the HIV-positive partner [56–59].

When the woman is HIV positive and the man is HIV negative, infection of her partner can be avoided by using artificial insemination techniques. When both partners are concordant for HIV, there is no risk of transmission, but there is potential for super infection with a different (and possibly drug-resistant) viral strain. To avoid this, artificial insemination procedures can be considered [38].

Fatherhood and men who have sex with men

Men who have sex with men (MSM) have traditionally fathered children in a number of ways, including having children in a previous or concurrent heterosexual relationship [60], forming a partnership with a woman [61], and using artificial insemination, semen donation or surrogate arrangements. They also become fathers by adoption and fostering children.

There has been a distinct lack of focus on the value of children for men who have sex with men (MSM) generally and HIV-positive, MSM specifically. A study in six US cities estimates that more than 7% of MSM and at least one-third of lesbians are parents [61]. Those men who do wish to become parents must overcome pressures of societal "norms" regarding who or what makes the best family. This is heightened for MSM, HIV-positive men, who, if they want to become parents, must overcome additional obstacles.

The thoughts and expectations of HIV-positive women have been researched, but those of men have been neglected. Prior to the HIV epidemic, Bigner and Jacobson (1989, 1992) investigated the value of children to MSM and heterosexual fathers. Comparisons between the two groups found that MSM fathers did not differ significantly in their desires to become parents, although their motivations for becoming parents were significantly different [62–64]. This was noted in differences on two motivational measures, namely tradition-continuity-security and social status.

A review of 23 empirical studies from 1978 to 2000 among children of lesbian mothers or MSM fathers (one Belgian/Dutch, one Danish, two British, and 18 North American) showed that the majority (20) reported on offspring of lesbian mothers, and three on MSM fathers. The study included 615 children with a wide age range who were contrasted with 387 controls on a series of measures. Children raised by lesbian mothers or MSM fathers did not systematically differ from other children on any of the seven outcome domains, including emotional functioning, sexual preference, stigma experience, and gender role behaviour [65].

Data on HIV-positive men in London were available for both heterosexual and MSM clinic attendees [4, 66]. Of the 84 MSM, 77.6% had not had any discussion with a doctor or nurse about the possibility of becoming a parent, with 68.2% feeling insufficiently informed. Approximately one-third had considered having children. Four had had a child prior to HIV diagnosis. Only 4.7% felt that they were fully informed about the issue, and 77.6% had not had any discussion with healthcare professionals about becoming a parent. Few men (4.7%) had considered sperm washing and no men had undergone sperm washing.

Three men reported fathering as a result of an unplanned pregnancy and four men had been involved in a planned pregnancy. More than half of the men questioned said that they would not have unprotected sex in order to conceive, although 38.2% would consider artificial insemination, 2.9% would definitely consider adoption, and 10.6% would definitely consider fostering. More than 90% believed that they would experience some discrimination. Of the sample, 29.4% believed that a child gave meaning to life, and 60% agreed with the statement that a baby would give them something to live for.

It is clear that significant proportions of HIV-positive MSM want children and would use a variety of routes to having a child if the opportunity was offered to them.

Fatherhood and drug use

In many countries, HIV infection among heterosexual groups is clustered around drug use as a risk factor. The issues surrounding fatherhood, HIV and drug use may have a direct effect on families. A study comparing drugusing fathers with a matched control group (n = 224) noted that drug use contributed to compromised fathering [67]. These results may reflect a skewed group as the drug-user fathers in this study were recruited from methadone maintenance programmes and may thus reflect a group already motivated to address or control their drug use and in contact with services.

Despite this potential positive bias, there were significant negative effects impacting on economic resources to support family formation, patterns of pair bonding, patterns of procreation and parenting behavior. The opioid-dependent fathers displayed: constricted personal definitions of the fathering role; poorer relationships with biological mothers; less co-residence with their children; lower economic provision; less parenting involvement; lower self-esteem as a father; and lower parenting satisfaction ratings. The researchers point out that such compromised fathering in itself may cause psychological distress to the father, as well as impaired parenting experience to the child [68].

A study of the adolescent children of drug-using, HIV positive fathers (n = 505) found direct associations between paternal distress and adolescent distress [69]. In addition, they described several indirect pathways, such as the link between paternal distress and impaired paternal teaching of coping skills, adolescent substance use, and ultimately, adolescent distress. They also report on a direct link between paternal drug addiction and/or HIV and adolescent distress. These data suggest that both drug use and HIV impact directly on fathers, as well as on their ability to parent their children.

Fathers and support of HIV-positive mothers

Although an understudied area, fathers are generally involved in pregnancy and their support may be key in a number of outcomes [84]. Studies that overlook paternal involvement run the risk of missing a crucial element in family composition, family dynamics and decision pathways. Male involvement in feeding decisions has been associated with increased ease of uptake of exclusive breastfeeding [70–72].

On the other hand, lack of male involvement or fear of male negative reaction has been clearly associated with lowered uptake or avoidance of HIV prevention and protection measures [73, 74]. Although many women fear negative reaction from partners when HIV-positive status is disclosed, studies have often recorded positive responses, such as support and financial assistance [75]. Disclosure patterns may often be culturally affected, and it is important to understand who the most desired disclosure contacts are [76].

Paternal disengagement

Within the HIV literature, there is a background echo, which may well be part of an ongoing myth, around paternal disengagement. Paternal disengagement is a concept that may need to be challenged in the absence of sound global data. Positive engagement in household life by men was reported in a longitudinal South African study. This positive engagement was often not supported or acknowledged [77].

There is good evidence that involving men and providing for risk reduction, particularly for men, can be effective. A systematic review of interventions for men and boys provided compelling evidence of the efficacy of such interventions, thus showing that interventions do exist and are effective and the barrier is one of reaching out to men rather, than the absence of effective tools to do so [78].

Yet there may be some variations and shifts in traditional roles, responsibilities and responses. HIV positive mothers were interviewed in Uganda to explore paternal involvement, as well as paternal kin support and future placement plans [79]. They found that half had fathers who were already deceased, one-third had fathers who were alive but non-resident with their children, and only 16% were residing with their fathers and being supported by them. Furthermore, contrary to cultural norms, mothers indicated preference for placement with maternal, rather than paternal, kin.

Families with HIV-positive mothers were compared with families with HIV-negative mothers, and found significant increased paternal absence and disengagement in the families with HIV-positive mothers [80]. In the USA, disclosure of HIV status was seen as similar to other diseases, but fathers disclosed later than mothers [81]. This may reflect clinic practice, and fathers being overlooked or excluded, as much as father behaviour. For example, White reported, "There was HIV discordancy in more than one-fifth of the parents' relationships. In over 46% of the relationships, the HIV status of the natural or birth father was not known because he was either untested or unavailable" [82]. Such a situation clearly indicates that including and reaching out to fathers is a specific strategy and may need a more family-oriented clinic approach to overcome such gaps.

Fathering an HIV-positive child can bring with it many stressors. Fathers of 31 HIV-positive children aged six to 18 years showed significantly elevated levels of both parenting and psychological distress compared with standardized norms [83]. These fathers requested a range of services, such as gender-specific support groups, assistance with child discipline, help with disease management, and support for future coping.

Fatherhood and child development

Research on child development has increasingly emphasized the importance of fathers [84]. The current era has seen a change in father roles, as well as a growth in understanding of such roles [85]. The literature on child development and paternal role in the presence of HIV is found in the "orphan" literature in studies that differentiate the gender of the deceased parent and explore the impact of paternal death on a variety of child outcomes.

Despite the fact that there is scant literature on the impact of HIV-positive fathers while they are alive, when they die, the ramifications are considerable. Although HIV is a key factor accounting for paternal death, there are other causes of mortality, such as violence, war, other illnesses and accidents. For example, more than a quarter of young South Africans reported that they had experienced a parental death [86]. Parental death in the HIV literature has been clouded by the fact that many studies do not differentiate between single parent death or dual parent death [87]. Furthermore, few disaggregate their data according to maternal or paternal death or proceed to analyze it separately. Those that do (n = 17) provide clear insight into the impact of paternal death on child development.

The findings are summarized in Table 2. Father presence exerts a protective factor on a range of child out comes and age at paternal loss is also important. Paternal death can affect economic environment, maternal mood, maternal health, access to treatment [88], access to schooling, migration from base families, and a number of other health and psychological out comes. These findings are complex as the effects of paternal death have implications on maternal health and wellbeing, as well as on child outcomes.

Conclusions

This paper clearly indicates the crucial role of fathers in family life and structure. The piecemeal state of the literature is lamentable. Where there is good evidence, it is clear that fathers and fathering is a central aspect of the HIV epidemic. Fathers play an important role in the family and their assistance can be harnessed if there is sufficient effort. Fathers can support mothers in the difficulties around infant feeding, early weaning and potential HIV disclosure through feeding practices.

Gender studies often explore lack of attention and provision for women, but in terms of family knowledge and response, the HIV literature on men generally and fathers specifically has specific oversights. Within this, some of the marginalized and difficult-to-reach groups are particularly hard hit. Fatherhood in the presence of HIV infection of the father and drug use in developing and resource-constrained countries, and for MSM, is not fully understood. Yet the loss of a father severely impacts on multiple facets of child development. Fatherhood and paternal contribution to families need to move to centre stage.

References

Antle BJ, Wells LM, Goldie RS, DeMatteo D, King SM: Challenges of parenting for families living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Work. 2001, 46 (2): 159-69.

Hosegood V, Madhavan : Data availability on men's involvement in families in sub-Saharan Africa to inform family-centred programmes for children affected by HIV and AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010, 13 (Suppl 2): S5-10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S5.

Nattabi B, Li J, Thompson SC, Orach CG, Earnest J: A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13 (5): 949-68. 10.1007/s10461-009-9537-y.

Sherr L, Barry N: Fatherhood and HIV-positive heterosexual men. HIV Med. 2004, 5: 258-63. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00218.x.

Sherr L: Strengthening families through HIV/AIDS prevention care treatment and support - a review. JLICA. 2008, [http://www.jlica.org/userfiles/file/SherrStrengtheningfamiliesthroughprevention,treatment.pdf]

Chen JL, Philips KA, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, Miu A: Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive men and women. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001, 33 (4): 144-152. 10.2307/2673717. 165

Panozzo L, Battegay M, Friedl A, Vernazza PL: Swiss Cohort Study: High risk behaviour and fertility desires among heterosexual HIV-positive patients with a serodiscordant partner-two challenging issues. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003, 133 (7-8): 124-127.

Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, Bekker LG, Shah I, Myer L: Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13 (Suppl 1): 38-46. 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1.

Myer L, Morroni C, Rebe K: Prevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected women and men receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007, 21 (4): 278-285. 10.1089/apc.2006.0108.

Paiva V, Filipe EV, Santos N, Lima TN, Segurado A: The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reprod Health Matters. 2003, 11 (22): 91-100. 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02293-6.

Paiva V, Santos N, França-Junior I, Filipe E, Ayres JR, Segurado : A desire to have children: gender and reproductive rights of men and women living with HIV: a challenge to health care in Brazil. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007, 21 (4): 268-277. 10.1089/apc.2006.0129.

Heys J, Kipp W, Jhangri GS, Alibhai A, Rubaale T: Fertility desires and infection with the HIV: results from a survey in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2009, 23 (Suppl 1): S37-45. 10.1097/01.aids.0000363776.76129.fd.

Nakayiwa S, Abang B, Packel L, Lifshay J, Purcell DW, King R, Ezati E, Mermin J, Coutinho A, Bunnell R: Desire for children and pregnancy risk behaviour among HIV-infected men and women in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10 (Suppl 4): S95-104. 10.1007/s10461-006-9126-2.

Oladapo OT, Daniel OJ, Odusoga OL, Ayoola-Sotubo O: Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive patients at a suburban specialist center. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005, 97 (12): 1672-1681.

Ndlovu V: Considering childbearing in the age of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): Views of HIV-positive couples. SAHARA J. 2009, 6 (2): 58-68.

Postma MJ, Beck EJ, Mandalia S, Sherr L, Walters MD, Houweling H, Jager JC: Universal HIV screening of pregnant women in England: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 1999, 318 (7199): 1656-1660.

Postma MJ, Beck EJ, Hankins CA, Mandalia S, Jager J, de Jong-van den Berg L, Walters M, Sherr L: Cost effectiveness of expanded antenatal HIV testing in London. AIDS. 2000, 14: 2383-2389. 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00020.

Theuring S, Mbezi P, Luvanda H, Jordan-Harder B, Kunz A, Harms G: Male involvement in PMTCT services in Mbeya Region, Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13 (Suppl 1): 92-102. 10.1007/s10461-009-9543-0.

Desgrées-du-Loû A, Orne-Gliemann J: Couple-centred testing and counselling for HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2008, 16 (32): 151-161. 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32407-0.

Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Kabura MN, John FN, Nduati RW, Mbori-Ngacha DA, John-Stewart GC: Antenatal couple counselling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004, 37 (5): 1620-1626. 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00016.

Katz DA, Kiarie JN, John-Stewart GC, Richardson BA, John FN, Farquhar C: HIV testing men in the antenatal setting: understanding male non-disclosure. Int J STD AIDS. 2009, 20 (11): 765-76. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009139.

Katz DA, Kiarie JN, John-Stewart GC, Richardson BA, John FN, Farquhar C: Male perspectives on incorporating men into antenatal HIV counselling and testing. PLoS One. 2009, 4 (11): e7602-10.1371/journal.pone.0007602.

Okonkwo KC, Reich K, Alabi AI, Umeike N, Nachman SA: An Evaluation of Awareness: Attitudes and Beliefs of Pregnant Nigerian Women toward Voluntary Counseling and Testing for HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007, 21 (4): 252-260. 10.1089/apc.2006.0065.

Baiden F, Remes P, Baiden R, Williams J, Hodgson A, Boelaert M, Buve A: Voluntary counselling and HIV testing for pregnant women in the Kassena-Nankan district of northern Ghana: Is couple counselling the way forward?. AIDS Care. 2005, 17 (5): 648-57.

Karamagi CAS, Tumwine JK, Tylleskar T, Heggenhougen K: Intimate partner violence against women in eastern Uganda: implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6: 284-10.1186/1471-2458-6-284.

Kowalczyk J, Jolly P, Karita E, Nibarere J-A, Vyankandondera J, Salibu H: Voluntary Counseling and testing for HIV Among Pregnant Women Presenting in labor in Kigali, Rwanda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2002, 31: 408-415.

Becker S, Mlay R, Schwandt HM, Lyamuya E: Comparing Couples' and Individual Voluntary Counseling and Testing for HIV at Antenatal Clinics in Tanzania: A Randomized Trial. AIDS Behav. 2009.

Bergenstrom A, Sherr L, Okolo S: HIV testing and prevention: family planning clinic attenders in London. Sex Transm Infect. 1999, 75: 130-

Bergenstrom A, Sherr L: HIV testing and prevention issues for women attending termination assessment clinics. Br J Fam Plann. 1999, 25: 3-8.

Gilling-Smith C, Nicopoullos JD, Semprini AE, Frodsham LC: HIV and reproductive care--a review of current practice. BJOG. 2006, 113 (8): 869-878. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00960.x.

Gilling-Smith C, Almeida P: HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C and infertility: reducing risk. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2003, 6: 106-112. 10.1080/1464770312331369343.

Apoola A, tenHof J, Allan PS: Access to infertility investigations and treatment in couples infected with HIV: questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2001, 323 (7324): 1285-10.1136/bmj.323.7324.1285.

Kalu E, Wood R, Vourliotis M, Gilling-Smith C: Fertility needs and funding in couples with blood-borne viral infection. HIV Med. 2009

van Leeuwen E, Wit FW, Repping S, Eeftinck Schattenkerk JK, Reiss P, van der Veen F, Prins JM: Effects of antiretroviral therapy on semen quality. AIDS. 2008, 22 (5): 637-642. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4de10.

van Leeuwen E, Wit FW, Prins JM, Reiss P, van der Veen F, Repping S: Semen quality remains stable during 96 weeks of untreated human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Fertil Steril. 2008, 90 (3): 636-641. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.102.

Coll O, Lopez M, Vidal R, Figueras F, Suy A, Hernandez S, Loncà M, Palacio M, Martinez E, Vernaeve V: Fertility assessment in non-infertile HIV-infected women and their partners. Reprod BiomedOnline. 2007, 14 (4): 488-494.

Ezeanochie M, Olagbuji B, Ande A, Oboro V: Fertility preferences, condom use, and concerns among HIV-positive women in serodiscordant relationships in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009, 107 (2): 97-98. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.06.013.

Fakoya A, Lamba H, Mackie N, Nandwani R, Brown A, Bernard E, Gilling-Smith C, Lacey C, Sherr L, Claydon P, Wallage S, Gazzard B: British HIV Association, BASHH and FSRH guidelines for the management of the sexual and reproductive health of people living with HIV infection 2008. HIV Med. 2008, 9 (9): 681-720. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00634.x.

Bagasra O, Farzadegan H, Seshamma T, Oakes JW, Saah A, Pomerantz RJ: Detection of HIV-1 proviral DNA in sperm from HIV-1-infected men. AIDS. 1994, 8 (12): 1669-1674. 10.1097/00002030-199412000-00005.

Vernazza PL, Gilliam BL, Dyer J, Fiscus SA, Eron JJ, Frank AC, Cohen MS: Quantification of HIV in semen: correlation with antiviral treatment and immune status. AIDS. 1997, 11 (8): 987-993. 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00006.

Quayle AJ, Xu C, Mayer KH, Anderson DJ: T lymphocytes and macrophages, but not motile spermatozoa, are a significant source of human immunodeficiency virus in semen. J Infect Dis. 1997, 176 (4): 960-968. 10.1086/516541.

Kim LU, Johnson MR, Barton S, Nelson MR, Sontag G, Smith JR, Gotch FM, Gilmour JW: Evaluation of sperm washing as a potential method of reducing HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples wishing to have children. AIDS. 1999, 13 (6): 645-651. 10.1097/00002030-199904160-00004.

Baccetti B, Benedetto A, Burrini AG, Collodel G, Elia C, Piomboni P, Renieri T, Sensini C, Zaccarelli M: HIV particles detected in spermatozoa of patients with AIDS. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1991, 23: 339-345.

Baccetti B, Benedetto A, Collodel G, di Caro A, Garbuglia AR, Piomboni P: The debate on the presence of HIV-1 in human gametes. J Reprod Immunol. 1998, 41 (1-2): 41-67. 10.1016/S0165-0378(98)00048-5.

Bujan L, Hollander L, Coudert M, Gilling-Smith C, Vucetich A, Guibert J, Vernazza P, Ohl J, Weigel M, Englert Y, Semprini AE, CREAThE network: Safety and efficacy of sperm washing in HIV-1-serodiscordant couples where the male is infected: results from the European CREAThE network. AIDS. 2007, 21 (14): 1909-1914. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282703879.

Sunderam S, Hollander L, Macaluso M, Vucetich A, Jamieson DJ, Osimo F, Duerr A, Semprini AE: Safe conception for HIV discordant couples through sperm-washing: experience and perceptions of patients in Milan, Italy. Reprod Health Matters. 2008, 16 (31): 211-219. 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31342-1.

Semprini AE, Bujan L, Englert Y, Smith CG, Guibert J, Hollander L, Ohl J, Vernazza P: Establishing the safety profile of sperm washing followed by ART for the treatment of HIV discordant couples wishing to conceive. Hum Reprod. 2007, 22 (10): 2793-2794. 10.1093/humrep/dem197.

Matthews LT, Mukherjee JS: Strategies for harm reduction among HIVaffected couples who want to conceive. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13 (Suppl 1): 5-11. 10.1007/s10461-009-9551-0.

de Vincenzi I: A longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1994, 331 (6): 341-346. 10.1056/NEJM199408113310601.

Baeten JM, Overbaugh J: Measuring the infectiousness of persons with HIV-1: opportunities for preventing sexual HIV-1 transmission. Curr HIV Res. 2003, 1 (1): 69-86. 10.2174/1570162033352110.

Mastro TD, de Vincenzi I: Probabilities of sexual HIV-1 transmission. AIDS. 1996, 10 (Suppl A): S75-82. 10.1097/00002030-199601001-00011.

Kalichman SC, Di Berto G, Eaton L: Human immunodeficiency virus viral load in blood plasma and semen: review and implications of empirical findings. Sex Transm Dis. 2008, 35 (1): 55-60. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318141fe9b.

Liuzzi G, Chirianni A, Clementi M, Bagnarelli P, Valenza A, Cataldo PT, Piazza M: Analysis of HIV-1 load in blood, semen and saliva: evidence for different viral compartments in a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. AIDS. 1996, 10 (14): F51-56.

Zhang H, Dornadula G, Beumont M, Livornese L, Van Uitert B, Henning K, Pomerantz RJ: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the semen of men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339 (25): 1803-1809. 10.1056/NEJM199812173392502.

Coombs RW, Speck CE, Hughes JP, Lee W, Sampoleo R, Ross SO, Dragavon J, Peterson G, Hooton TM, Collier AC, Corey L, Koutsky L, Krieger JN: Association between culturable human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in semen and HIV-1 RNA levels in semen and blood: evidence for compartmentalization of HIV-1 between semen and blood. J Infect Dis. 1998, 177 (2): 320-330. 10.1086/514213.

Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, Meehan MO, Lutalo T, Gray RH: Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342 (13): 921-929. 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303.

Castilla J, Del Romero J, Hernando V, Marincovich B, Garcia S, Rodriguez C: Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005, 40 (1): 96-101. 10.1097/01.qai.0000157389.78374.45.

Barreiro P, del Romero J, Leal M, Hernando V, Asencio R, de Mendoza C, Labarga P, Núñez M, Ramos JT, González-Lahoz J, Soriano V, Spanish HIV Discordant Study Group: Natural pregnancies in HIV-serodiscordant couples receiving successful antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006, 43 (3): 324-326. 10.1097/01.qai.0000243091.40490.fd.

Melo M, Varella I, Nielsen K, Turella L, Santos B: Demographic characteristics, sexual transmission and CD4 progression among heterosexual HIVserodiscordant couples followed in Porto Algegre, Brazil. 16th International AIDS Conference, Toronto TUPE0430. 2006

Khan SI, Hudson-Rodd N, Saggers S, Bhuiya A: Men who have sex with men's sexual relations with women in Bangladesh. Cult Health Sex. 2005, 7 (2): 159-169. 10.1080/13691050412331321258.

Cameron P, Cameron K: Homosexual parents. Adolescence. 1996, 31 (124): 757-776.

Bigner JJ, Jacobsen RB: Adult responses to child behavior and attitudes toward fathering: gay and nongay fathers. J Homosex. 1992, 23 (3): 99-112. 10.1300/J082v23n03_07.

Bigner JJ, Jacobsen RB: The value of children to gay and heterosexual fathers. J Homosex. 1989, 18 (1-2): 163-172. 10.1300/J082v18n01_08.

Bigner JJ, Jacobsen RB: Parenting behaviors of homosexual and heterosexual fathers. J Homosex. 1989, 18 (1-2): 163-172. 10.1300/J082v18n01_08.

Anderssen N, Amlie C, Ytterøy EA: Outcomes for children with lesbian or gay parents. A review of studies from 1978 to 2000. Scand J Psychol. 2002, 43 (4): 335-351. 10.1111/1467-9450.00302.

Sherr L, Barry N: Fatherhood and HIV - overlooked and understudied. Abstract no. 1034. 2nd IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment. 2003

McMahon TJ, Winkel JD, Rounsaville BJ: Drug abuse and responsible fathering: a comparative study of men enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment. Addiction. 2008, 103 (2): 269-283. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02075.x.

McMahon TJ, Rounsaville BJ: Substance abuse and fathering: adding poppa to the research agenda. Addiction. 2002, 97 (9): 1109-1115. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00159.x.

Brook DW, Brook JS, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Castro FG, Tiburcio N: Risk factors for distress in the adolescent children of HIV-positive and HIVnegative drug-abusing fathers. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (1): 93-100. 10.1080/09540120701426557.

Tijou Traoré A, Querre M, Brou H, Leroy V, Desclaux A, Desgrées-du-Loû A: Couples, PMTCT programs and infant feeding decision-making in Ivory Coast. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 69 (6): 830-837. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.001.

Matovu A, Kirunda B, Rugamba-Kabagambe G, Tumwesigye NM, Nuwaha F: Factors influencing adherence to exclusive breast feeding among HIV positive mothers in Kabarole district, Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2008, 85 (4): 162-170.

Msuya SE, Mbizvo EM, Hussain A, Uriyo J, Sam NE, Stray-Pedersen B: Low male partner participation in antenatal HIV counselling and testing in northern Tanzania: implications for preventive programs. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (6): 700-709. 10.1080/09540120701687059.

Kebaabetswe PM: Barriers to participation in the prevention of mother-tochild HIV transmission program in Gaborone, Botswana a qualitative approach. AIDS Care. 2007, 19 (3): 355-360. 10.1080/09540120600942407.

Moth IA, Ayayo ABCO, Kaseje DO: Assessment of utilisation of PMTCT services at Nyanza Provincial Hospital, Kenya. SAHARA. 2005, 2 (2): 244-250.

Ezegwui HU, Nwogu-Ikojo EE, Enwereji JO, Dim CC: HIV serostatus disclosure pattern among pregnant women in Enugu, Nigeria. J Biosoc Sci. 2009, 41 (6): 789-798. 10.1017/S0021932009990137.

De Baets AJ, Sifovo S, Parsons R, Pazvakavambwa IE: HIV disclosure and discussions about grief with Shona children: a comparison between health care workers and community members in Eastern Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 66 (2): 479-491. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.028.

Montgomery CM, Hosegood V, Busza J, Timaeus IM: Men's involvement in the South African family: engendering change in the AIDS era. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 62 (10): 2411-2419. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.026.

Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M, Olukoya A, Santos C: Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: Evidence of impact. Glob Public Health. 2009, 9: 1-15. 10.1080/17441690902942464.

Hodge DR, Roby JL: Sub-Saharan African women living with HIV/AIDS: an exploration of general and spiritual coping strategies. Soc Work. 2010, 55 (1): 27-37.

Pelton J, Forehand R, Morse E, Morse PS, Stock M: Father-child contact in inner-city African American families with maternal HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2001, 13 (4): 475-480. 10.1080/09540120120058003.

Lee MB, Rotheram-Borus MJ: Parents' disclosure of HIV to their children. AIDS. 2002, 16 (16): 2201-2207. 10.1097/00002030-200211080-00013.

White J, Melvin D, Moore C, Crowley S: Parental HIV discordancy and its impact on the family. AIDS Care. 1997, 9 (5): 609-615. 10.1080/713613199.

Wiener LS, Vasquez MJ, Battles HB: Brief report: fathering a child living with HIV/AIDS: psychosocial adjustment and parenting stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001, 26 (6): 353-358. 10.1093/jpepsy/26.6.353.

Lamb ME: Male roles in families "at risk": the ecology of child maltreatment. Child Maltreat. 2001, 6 (4): 310-313. 10.1177/1077559501006004004.

Cabrera NJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bradley RH, Hoff erth S, Lamb ME: Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Dev. 2000, 71 (1): 127-136. 10.1111/1467-8624.00126.

Operario D, Pettifor A, Cluver L, MacPhail C, Rees H: Prevalence of parental death among young people in South Africa and risk for HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 44 (1): 93-98. 10.1097/01.qai.0000243126.75153.3c.

Sherr L, Varrall R, Mueller J, JLICA Workgroup 1 Members, Richter L, Wakhweya A, Adato M, Belsey M, Chandan U, Drimie S, Haour-Knipe Victoria Hosegood M, Kimou J, Madhavan S, Mathambo V, Desmond C: A systematic review on the meaning of the concept 'AIDS Orphan': confusion over definitions and implications for care. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (5): 527-533. 10.1080/09540120701867248.

Kiboneka A, Nyatia RJ, Nabiryo C, Anema A, Cooper CL, Fernandes KA, Montaner JS, Mills EJ: Combination antiretroviral therapy in population affected by conflict: outcomes from large cohort in northern Uganda. BMJ. 2009

Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, Orner P, Bracken H, Zweigenthal V: "Life is still going on": reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 65 (2): 274-283. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019.

Ko N, Muecke M: To reproduce or not: HIV-concordant couples make a critical decision during pregnancy. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 2005, 50 (1): 23-30. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.08.003.

Smith DJ, Mbakwem BC: Life projects and therapeutic itineraries: marriage, fertility, and antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. AIDS. 2007, 21 (Suppl 5): S37-41. 10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af.

Thurman TR, Brown L, Richter L, Maharaj P, Magnani R: Sexual risk behavior among South African adolescents: is orphan status a factor?. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10 (6): 627-635. 10.1007/s10461-006-9104-8.

Beegle K, De Weerdt J, Dercon S: The intergenerational impact of the African orphans crisis: a cohort study from an HIV/AIDS affected area. Int J Epidemiol. 2009, 38 (2): 561-568. 10.1093/ije/dyn197.

Vreeman RC, Wiehe SE, Ayaya SO, Musick BS, Nyandiko WM: Association of antiretroviral and clinic adherence with orphan status among HIV-infected children in Western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 49 (2): 163-170. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318183a996.

Birdthistle IJ, Floyd S, Machingura A, Mudziwapasi N, Gregson S, Glynn JR: From affected to infected? Orphanhood and HIV risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2008, 22 (6): 759-766. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4cac7.

Hosegood V, Floyd S, Marston M, Hill C, McGrath N, Isingo R, Crampin A, Zaba B: The effects of high HIV prevalence on orphanhood and living arrangements of children in Malawi, Tanzania, and South Africa. Popul Stud (Camb). 2007, 61 (3): 327-336. 10.1080/00324720701524292.

Ford K, Hosegood V: AIDS mortality and the mobility of children in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Demography. 2005, 42 (4): 757-768. 10.1353/dem.2005.0029.

Doring M, França Junior I, Stella IM: Factors associated with institutionalization of children orphaned by AIDS in a population-based survey in Porto Alegre, Brazil. AIDS. 2005, 19 (Suppl 4): S59-63. 10.1097/01.aids.0000191492.43865.63.

Watts H, Lopman B, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S: Rising incidence and prevalence of orphanhood in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998 to 2003. AIDS. 2005, 19 (7): 717-725. 10.1097/01.aids.0000166095.62187.df.

Nyamukapa C, Gregson S: Extended family's and women's roles in safeguarding orphans' education in AIDS-afflicted rural Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 60 (10): 2155-2167.

Crampin AC, Floyd S, Glynn JR, Madise N, Nyondo A, Khondowe MM, Njoka CL, Kanyongoloka H, Ngwira B, Zaba B, Fine PE: The long-term impact of HIV and orphanhood on the mortality and physical well-being of children in rural Malawi. AIDS. 2003, 17 (3): 389-397. 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00013.

Lindblade KA, Odhiambo F, Rosen DH, DeCock KM: Health and nutritional status of orphans <6 years old cared for by relatives in western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8 (1): 67-72. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.00987.x.

Thorne C, Newell ML, Peckham C: Social care of children born to HIV-infected mothers in Europe. European Collaborative Study. AIDS Care. 1998, 10 (1): 7-16. 10.1080/713612346.

Kang M, Dunbar M, Laver S, Padian N: Maternal versus paternal orphans and HIV/STI risk among adolescent girls in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (2): 214-217. 10.1080/09540120701534715.

Parikh A, Desilva MB, Cakwe M, Quinlan T, Simon JL, Skalicky A, Zhuwau T: Exploring the Cinderella myth: intrahousehold differences in child wellbeing between orphans and non-orphans in Amajuba District, SouthAfrica. AIDS. 2007, 21 (Suppl 7): S95-S103. 10.1097/01.aids.0000300540.12849.86.

Timaeus IM, Boler T: Father figures: the progress at school of orphans in South Africa. AIDS. 2007, 21 (Suppl 7): S83-93. 10.1097/01.aids.0000300539.35720.a0.

Bhargava A: AIDS epidemic and the psychological well-being and school participation of Ethiopian orphans. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2005, 10 (3): 263-276. 10.1080/13548500412331334181.

Foster G, Shakespeare R, Chinemana F, Jackson H, Gregson S, Marange C, Mashumba S: Orphan prevalence and extended family care in a peri-urban community in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1995, 7 (1): 3-17. 10.1080/09540129550126911.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

This manuscript was conceived, drafted and authored by LS. Assistance in gathering references for the systematic review is acknowledged (N. Jahn). Assistance in the empirical study (N. Barry) is acknowledged.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sherr, L. Fathers and HIV: considerations for families. JIAS 13 (Suppl 2), S4 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S4