Abstract

Background

Malaria vector control in Sudan relies mainly on indoor residual spraying (IRS) and the use of long lasting insecticide treated bed nets (LLINs). Monitoring insecticide resistance in the main Sudanese malaria vector, Anopheles arabiensis, is essential for planning and implementing an effective vector control program in this country.

Methods

WHO susceptibility tests were used to monitor resistance to insecticides from all four WHO-approved classes of insecticide at four sentinel sites in Gezira state over a three year period. Insecticide resistance mechanisms were studied using PCR and microarray analyses.

Results

WHO susceptibility tests showed that Anopheles arabiensis from all sites were fully susceptible to bendiocarb and fenitrothion for the duration of the study (2008–2011). However, resistance to DDT and pyrethroids was detected at three sites, with strong seasonal variations evident at all sites. The 1014 F kdr allele was significantly associated with resistance to pyrethroids and DDT (P < 0.001) with extremely high effects sizes (OR > 7 in allelic tests). The 1014S allele was not detected in any of the populations tested. Microarray analysis of the permethrin-resistant population of An. arabiensis from Wad Medani identified a number of metabolic genes that were significantly over-transcribed in the field-collected resistant samples when compared to the susceptible Sudanese An. arabiensis Dongola strain. These included CYP6M2 and CYP6P3, two genes previously implicated in pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.s, and the epsilon-class glutathione-S-transferase, GSTe4.

Conclusions

These data suggest that both target-site mechanisms and metabolic mechanisms play an important role in conferring pyrethroid resistance in An. arabiensis from Sudan. Identification in An. arabiensis of candidate loci that have been implicated in the resistance phenotype in An. gambiae requires further investigation to confirm the role of these genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sudan, in 2010, accounted for the highest number of malaria cases in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region (WHO/EMR), and was responsible for 58% of the total regional malaria cases[1]. The 2007 National Strategic Plan for Malaria in Sudan aimed to reduce morbidity and mortality of malaria by 50% by 2012 (National Malaria Control Programme, unpublished data). The use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) are the main components of most malaria prevention and control strategies because they are highly effective and have a relatively low cost. Currently there are only four classes of insecticides approved for IRS (pyrethroids, organochlorines, organophosphates and carbamates), and only one class, the pyrethroids, allowed for use on LLINs[2]. Given the importance of insecticide use in malaria vector control, and the continuous development of insecticide resistance in malaria mosquitoes, monitoring the susceptibility of vectors to pyrethroids and the other insecticide classes is essential. Furthermore, it is necessary to identify the resistance mechanisms involved[2, 3] in order to formulate evidence-based resistance management strategies.

Malaria vector control in Sudan has a long history[4]. The main vector control interventions include IRS and the use of LLINs, chemical larviciding of water bodies/breeding sites, environmental management and some, albeit limited, biological control. The Sudanese Ministry of Health (MOH) has provided free distribution of LLINs in Gezira state since 2005[1].

Insecticide resistance is widespread in the major African vectors belonging to the Anopheles gambiae complex[5–8] and in particular, resistance to pyrethroids has been shown to hamper malaria control programmes[9]. Anopheles arabiensis is the main vector in central Sudan and multiple insecticide resistance has been reported in Sudanese populations of this species. This includes resistance to the organochlorides benzene hexachloride (BHC) and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)[10], the organophosphate malathion[11] and to various pyrethroids[12].

The two best understood mechanisms of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes are target site insensitivity and metabolic resistance[13]. Target site insensitivity to pyrethroids and DDT is a result of changes in the neuronal voltage-gated sodium ion channel (VGSC). In An. gambiae s.s., two point mutations at amino acid position 1014 of the VGSC have been described, resulting in either a leucine to phenylalanine (L1014F)[14], or a leucine to serine (L1014S) substitution[15]. Both of these knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations have been shown to be associated with DDT and pyrethroid resistance phenotypes[15–17]. In An. arabiensis, kdr mutations have been found in several widely dispersed locations including Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Uganda and Sudan[12, 18–21].

Metabolic resistance is generally associated with three large enzyme families: the cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450s), carboxyl/cholinesterases (CCEs), and glutathione-S transferases (GSTs)[22]. Little information is available on the metabolic resistance mechanisms present in Sudanese An. arabiensis populations although Hemingway[11, 23] did implicate a carboxylesterase gene in resistance to malathion. Recently, Nardini et al.[21] reported that one P450 gene, CYP9L1, showed increased transcription in a Sudanese DDT selected laboratory strain (SENN-DDT) compared to an unselected susceptible strain.

In the present study, we describe the insecticide resistance patterns of An. arabiensis populations from central Sudan over a three year period, and report the principle mechanisms responsible for the observed resistance to pyrethroids and DDT. Results from this study will guide the development of effective insecticide resistance management strategies in Sudan.

Methods

Study area

This study was carried out in Gezira state in central Sudan. The state is situated in a rich savanna environment. The area has a hot dry summer from April to June with daily temperatures between 32-42°C, and relative humidity of 20%. The rainy season starts in late June and ends in October. Winter is relatively cold and dry and occurs from December to February, with daily temperatures between 15-21°C, and a relative humidity of 30% (Sudan Meteorological Services, 2005, unpublished data).

Four sentinel sites were identified for biannual resistance monitoring (Figure 1). These sites were chosen to cover a range of insecticide selection pressures. These included an urban site with local use of insecticides in subsistence agriculture (Wad Medani), a rural site with intensive crop cultivation (Elmanagil), a site with very high coverage of insecticide-based malaria control interventions (Wad Elhadad) and a site with no intensive agriculture and no organized vector control programme (Rufaa).

Mosquito collections

Anopheles mosquitoes were collected between October 2008 and January 2011. Two rounds of collections were performed every year in each of the four sites to coincide with the two peaks of malaria transmission seasons (October/November - the period towards the end of the wet season; and January - the dry season). Mosquitoes were collected as larvae and transferred to the BNNICD (Blue Nile National Institute for Communicable Diseases) insectary and reared to the adult stage to be used for WHO insecticide susceptibility tests. Samples were taken from multiple breeding sites within a 10 km radius and collections undertaken over several days to minimize the probability of analyzing siblings from a single female.

WHO bioassay tests

Larvae were reared to the adult stage, morphologically identified, and only Anopheles gambiae s.l. non-blood fed, 3–5 day old adult females were used for the insecticide bioassays. Insecticide papers were obtained from the WHO reference centre in Malaysia. Each batch was tested on the insecticide susceptible Kisumu strain of An. gambiae at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine before dispatch to Sudan. Five insecticides were tested: 4% DDT (organochlorine), 0.75% permethrin (type I pyrethroid), 0.05% deltamethrin (type II pyrethroid), 0.1% bendiocarb (carbamate) and 1% fenitrothion (organophosphate) according to standard WHO protocols[24].

Mosquito identification and kdr mutation detection

From each sentinel site and for each insecticide, 30–50 mosquitoes taken from the control exposure as well as 20 specimens that survived exposure and 20 specimens that died, were identified to species level using PCR[25]. The hydrolysis probe/Taqman®-kdr assay[26] was used for the detection of the L1014F and L1014S mutations from pyrethroid/DDT bioassay survivors and dead specimens.

Data analysis

Susceptibility status of mosquito populations was evaluated according to WHO criteria[2]. Mortality greater than 98% indicates susceptibility, mortality less than 98% suggests resistance and needs further investigation, and mortality of 90% or lower confirms insecticide resistance. Mortalities in the control groups were less than 5%, thus no corrections using Abbott’s formula were required[27]. A two sample t-test was used to compare the differences in mortalities between the two different seasons during each year of collection and to check for significant change in mortalities over the three years. Analyses were undertaken for each insecticide using Statistix7 analytical software. Regression analysis was used to compare the kdr allele frequencies over the three years. Allelic association between kdr and resistance, and odds ratios, were calculated in Vassar Stats (http://vassarstats.net/odds2x2.html).

Microarray analysis

Microarray analysis was performed to test for gene transcription differences between three sample conditions: Wad Medani resistant mosquitoes (survived 120 minute exposure to permethrin, which is equivalent to an LT80), Wad Medani unexposed, and the control DONG (susceptible An. arabiensis strain from Dongola in North Sudan, susceptible to all known insecticides; housed at BNNICD, Sudan and the Botha de Meillon Insectary, National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), South Africa).

For each biological condition, total RNA was extracted from 5 pools of 15, 3 day old unfed female mosquitoes using the Arcturus PicoPure Kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) with an on-column DNase digestion (RNase-Free DNase , Qiagen, UK). Total RNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, USA) and quality assessed using the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Assay on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Stockport, UK). RNA pools (100 ng total) were labeled separately with Cy3 and/or Cy5 using the Agilent Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Labeled RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), eluted in 30 μl water, and quantity and quality determined as above. All samples passed the yield and specific activity thresholds recommended by Agilent. Cy3-labelled cRNA (300 ng) and Cy5-labelled cRNA (300 ng) were combined and hybridised to the AGAM-15 K chip[28].

The experimental design for microarray comparisons is depicted in Additional file1: Figure S1. Hybridization, washing, scanning and feature extraction were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Analysis was undertaken in GeneSpring GX 11 (Agilent Technologies) following filtering out of all probes where either red or green signal was not significantly above background. A 2-fold cut-off with probability ≤0.05 (FDR adjusted;[29]) was applied to all features in order to determine significance. All data have been submitted to ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/miamexpress/) with accession number E-MEXP-3656.

qPCR validation

The microarray results were validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR).

Fold-change differences between Wad Medani resistant and Dongola (susceptible) were calculated for CYP6P3, CYP6Z3 and GSTe4 with normalization to the control ribosomal reference gene RSP7. Primer sequences are provided in Table 1.

Superscript III (Invitrogen) was used to produce cDNA for qPCR. All cDNA samples were cleaned using the PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) prior to use. A 2-fold dilution series of template cDNA was used to produce the required standard curves. All reactions were prepared in triplicate in 20 μl volumes containing 1× Agilent Brilliant III SYBR qPCR Mastermix, 300 nM of each primer, and 1 μl template RNA (100 ng/ul). Reactions were performed using the Agilent MX3005 qPCR system. The cycling conditions were 3 min at 95°C followed by 10s at 95°C, 10s at 60°C (40 cycles). The ΔΔCt method was used for calculation of fold change values[30].

Results

WHO bioassay tests

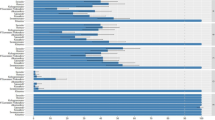

A total of six collection rounds were conducted at four sentinel sites in central Sudan from October 2008 to January 2011 (two rounds per year). During each year of collection, around 2, 270 adult mosquitoes reared from larval collections were exposed (400–450 per insecticide) to five insecticides (permethrin, deltamethrin, DDT, bendiocarb and fenitrothion). Figure 2 shows the susceptibility/resistance status of An. gambiae s.l. in these collections. Identification to species level revealed only the presence of An. arabiensis from all four sentinel sites. They were fully susceptible to bendiocarb (carbamate) and fenitrothion (organophosphate) at all four sites (data not shown).

High frequencies of permethrin and DDT resistance were observed over the three years of monitoring in the urban agricultural area of Wad Medani, and in Rufaa, the area with low insecticide exposure (Figure 2).

Two sample t-tests were used to analyse the differences in susceptibility between the different seasons for each insecticide for each of the three years. Tables 2 and3 summarize the results of comparisons between seasons within sites, and between years within sites respectively. Seasonal variations were most pronounced in Wad Medani with resistance more pronounced in the wet season than the dry.

Detection of kdr

The 1014 F allele was significantly associated with resistance to pyrethroids and DDT in all seasons (P < 0.001) with effect sizes (odds ratios) ranging from 7.8 to 15.5 in allelic tests (Table 4 and Additional file2: Table S1). The L1014S mutation was not detected in any specimens.

Microarray analysis

No significantly differentially expressed genes were detected between the Wad Medani population that survived exposure to the permethrin LT80 and theWad Medani unexposed controls (Additional file3: Table S2). However, in comparisons of Wad Medani resistant samples with the DONG susceptible strain 1,341 probes showed differential transcription levels (FC ≥ 2; P < 0.05; Additional file3: Table S2 and Additional file4: Table S3). The lowest p values were for unidentified proteins followed by trypsins and chymotrypsins (Additional file4: Table S3). However, numerous detoxification genes were over expressed in the permethrin resistant field population compared to the laboratory susceptible colony (Table 5). Genes from the three families commonly associated with insecticide metabolism are each represented by 4 probes on the array and genes for which all four probes were significant, and whose maximum fold change was greater than 5 were selected as the strongest candidates. This candidate list included CYP6Z3, CYP6M2, CYP6P3, and GSTe4.

qPCR analysis

qPCR validated the microarray results for CYP6P3 (microarray FC = 12.45; qPCR FC = 13.35) and for GSTe4 (microarray FC = 2.41; qPCR FC = 3.2). For CYP6Z3, the FC value obtained from microarray analysis (10.39) was lower than that obtained using qPCR (21.35) but was still significant.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that insecticide resistance is present in Sudanese vector populations[10–12, 23, 31, 32]. The present study extends this work through evaluation of the resistance status of An. arabiensis over three years of monitoring in areas with different levels of insecticide exposure and explores the difference in resistance patterns between the two different seasons of malaria transmission.

Anopheles arabiensis was the only member of the An. gambiae complex found in Gezira state, as has been demonstrated previously[4, 12, 32, 33]. The field population of An. arabiensis collected from Gezira state was susceptible to bendiocarb (a carbamate) and fenitrothion (organophosphate). Bendiocarb is currently used for IRS in Gezira state. It was first applied for public health purposes in central Sudan in 2007 when An. arabiensis showed strong resistance to the pyrethroid insecticide, permethrin[12].

Anopheles arabiensis from central Sudan exhibited resistance to permethrin, DDT and deltamethrin. The most resistant population was found in Wad Medani, an urban agricultural site. The presence of multiple insecticide resistance in the study area is consistent with previous studies[12, 31, 32]. There is strong variation in mortality rates between the two different seasons of each year of collection (wet/dry). For example, in Wad Medani, permethrin and DDT resistance during the 2008–2009 rounds of collections was high with mortality rates of 33% and 35.5% respectively during the wet season. During the dry season, the mortality rates increased to 89% and 73.4% for permethrin and DDT respectively. The same trend is observed for deltamethrin where the mortality was 73.2% during the wet season and 100% during the dry season. Such seasonal variations in susceptibility of Anopheles mosquitoes to insecticides have been reported in Burkina Faso[34], Benin[35] and Chad[36].

Resistance in the mosquito population to permethrin, and the reduced susceptibility to deltamethrin in Wad Elhadad, a site of intensive LLIN coverage, may have developed as a result of sustained exposure of adult mosquitoes to these insecticides from LLINs. DDT is currently not used in Sudan, however, high levels of resistance were still observed. DDT resistance was strongly associated with the L1014F mutation and it is possible that recent pyrethroid use has selected for this cross-resistance mechanism. As a result, high levels of DDT resistance was observed, even in areas where DDT use had been discontinued for a number of years. Similar results were reported in the same area in previous studies[12, 32]. The kdr allele 1014 F is strongly associated with resistance in these populations. Effects sizes (Odds Ratios) are high; in allelic tests they are similar to the values reported previously for effects sizes of kdr in Ghanaian and Cameroonian An. gambiae[37].

While 1014 F imparts a dramatic effect on resistance, it does not completely explain the resistance phenotype since many 1014 L homozygotes survive 1 hr exposure to pyrethroids and DDT, suggesting that alternative mechanisms of resistance are operating in this population. This phenomenon has been described before[21, 38, 39].

In order to investigate the metabolic resistance mechanisms involved in the resistance of these field populations, a whole genome microarray approach was used. In comparisons of An. arabiensis from Wad Medani, which survived exposure to permethrin equivalent to an LT80, with the susceptible DONG strain, a large number of genes showed significantly different transcription levels. The most significantly over-transcribed genes were trypsins, chymotrypsins and loci of no known function for which the relationship with resistance is difficult to investigate. A number of detoxification genes were also significantly over-transcribed, including genes with known roles in permethrin metabolism, e.g. CYP6P3 and CYP6M2, both of which have been demonstrated to be capable of metabolising pyrethroids in vitro[40, 41]. In addition to this, CYP6M2 was recently shown to also metabolise DDT[28]. The highest over-transcribed candidate was the glutathione-S-transferase GSTe4 which exhibits >15 fold mRNA expression in the resistant strain. Whilst GSTs have recognised roles in DDT metabolism, they may also be associated with pyrethroid resistance[42].

No significantly over-transcribed probes were detected in comparisons of Wad Medani resistant samples with unexposed controls from the same site. However, this may be explained by significant effects of 1014 F on resistance since samples for microarray were not matched for kdr status. In addition, there is reduced power to detect gene expression differences in comparisons of resistant samples with unexposed controls since these, by definition, will contain resistant individuals. The high levels of resistance and the importance of both target-site and metabolic processes in the resistance phenotype indicate that continued monitoring of expression of detoxification loci in resistant populations of An. arabiensis is necessary.

Whether the resistance found in central Sudan is due to agricultural usage of chemicals, domestic aerosols/coils/ITNs for personal protection or from malaria vector control activities is difficult to assess as we do not have data on the types or quantities of chemicals used for agriculture or domestic use. What is clear, however, is that resistance has been found at all four study sites, albeit at different frequencies. This endorses the malaria vector control programme’s implementation of a resistance management strategy for central Sudan, as mentioned above, along the lines advocated by the WHO Global Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management[2].

Conclusions

This study reports strong seasonal variation in the susceptibility levels to pyrethroids and DDT in Gezira state. The results obtained in this study will enable informed choice of insecticides for use in vector control programmes in Gezira state. In addition, the data obtained will provide baseline information needed in the monitoring of the susceptibility of An. arabiensis to the carbamate insecticide bendiocarb currently being used by the vector control programme for indoor residual house spraying.

References

World Health Organization: World Malaria Report 2010. 2012, Geneva: WHO

World Health Organization: Global Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management in malaria vectors. 2012, Geneva: WHO

McCarroll L, Hemingway J: Can insecticide resistance status affect parasite transmission in mosquitoes?. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002, 32: 1345-1351. 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00097-8.

El Gaddal AA, Haridi AM, Hassan FT, Hussein H: Malaria in the Gezira Managil Irrigated Scheme of the Sudan. J Trop Med Hyg. 1985, 88: 153-159.

Coetzee M, Horne DWK, Brooke BD, Hunt RH: DDT, dieldrin and pyrethroid insecticide resistance in African malaria vector mosquitoes: an historical review and implications for future malaria control in southern Africa. Sth Afr J Sci. 1999, 95: 215-218.

Hargreaves K, Hunt RH, Brooke BD, Mthembu J, Weeto MM, Awolola TS, Coetzee M: Anopheles arabiensis and An. quadriannulatus resistance to DDT in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2003, 17: 417-422. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2003.00460.x.

Santolamazza F, Calzetta M, Etang J, Barrese E, Dia I, Caccone A, Donnelly MJ, Petrarca V, Simard F, Pinto J, Torre A: Distribution of knock-down resistance mutations in Anopheles gambiae molecular forms in west and west-central Africa. Malar J. 2008, 7: 74-10.1186/1475-2875-7-74.

Ranson H, N'Guessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V: Pyrethroid resistance in African anopheline mosquitoes: what are the implications for malaria control?. Trends Parasitol. 2011, 27: 91-98. 10.1016/j.pt.2010.08.004.

Sharp B, Ridl F, Govender D, Kuklinski J, Kleinschmidt I: Malaria vector control by indoor residual insecticide spraying on the tropical island of Bioko. Equatorial G Malar J. 2007, 6: 52-10.1186/1475-2875-6-52.

Haridi A: Inheritance of DDT resistance in species A and B of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Bull Wld Hlth Org. 1972, 47: 619-626.

Hemingway J: Biochemical studies on Malathion resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from Sudan. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983, 77: 477-480. 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90118-9.

Abdalla H, Matambo TS, Koekemoer LL, Mnzava AP, Hunt RH, Coetzee M: Insecticide susceptibility and vector status of natural populations of Anopheles arabiensis from Sudan. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102: 263-271. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.10.008.

Hemingway J, Ranson H: Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000, 45: 371-391. 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.371.

Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williams MS, Darriet F, Berge JB, Devonshire AL, Guillet P, Pasteur N, Pauron D: Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol. 1998, 7: 179-184. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1998.72062.x.

Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule JM, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins FH: Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol. 2000, 9: 491-497. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00209.x.

Chandre F, Darriet F, Duchon S, Finot L, Manguin S, Carnevale P, Guillet P: Modifications of pyrethroid effects associated with kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 14: 81-88. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00212.x.

Kolaczinski JH, Fanello C, Herve J-P, Conway DJ, Carnevale P, Curtis CF: Experimental and molecular genetic analysis of the impact of pyrethroid and non-pyrethroid insecticide impregnated bednets for mosquito control in an area of pyrethroid resistance. Bull Entomol Res. 2000, 90: 125-132.

Diabate A, Baldet T, Chandre F, Dabire KR, Simard F, Ouedraogo JB, Guillet P, Hougard JM: First report of a kdr mutation in Anopheles arabiensis from Burkina Faso, West Africa. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2004, 20: 195-196.

Kulkarni MA, Rowland M, Alifrangis M, Mosha FW, Matowo J, Malima R, Peter J, Kweka E, Lyimo I, Magesa S, Salanti A, Rau ME, Drakeley C: Occurrence of the leucine-to-phenylalanine knockdown resistance (kdr) mutation in Anopheles arabiensis populations in Tanzania, detected by a simplified high-throughput SSOP-ELISA method. Malar J. 2006, 5: 56-10.1186/1475-2875-5-56.

Verhaeghen K, Bortel WV, Roelants P, Backeljau T, Coosemans M: Detection of the East and West African kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis from Uganda using a new assay based on FRET/Melt Curve analysis. Malar J. 2006, 5: 16-10.1186/1475-2875-5-16.

Nardini L, Christian RN, Coetzer N, Ranson H, Coetzee M, Koekemoer LL: Detoxification enzymes associated with insecticide resistance in laboratory strains of Anopheles arabiensis of different geographic origin. Parasit Vectors. 2012, 5: 113-10.1186/1756-3305-5-113.

Ranson H, Claudianos C, Claudianos C, Ortelli F, Abgrall C, Hemingway J, Sharakhova MV, Unger MF, Collins FH, Feyereisen R: Evolution of supergene families associated with insecticide resistance. Science. 2002, 298: 179-181. 10.1126/science.1076781.

Hemingway J: Malathion carboxylesterase enzymes in Anopheles arabiensis from Sudan. Pest B Physiol. 1985, 23: 309-313. 10.1016/0048-3575(85)90091-4.

World Health Organization: Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vectors, bio-efficacy and persistence of insecticides on treated surfaces. WHO/CDS/CPC/MAL/98.12. 1998, Geneva: WHO

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH: Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993, 49: 520-529.

Bass C, Nikou D, Donnelly MJ, Williamson MS, Ranson H, Ball A, Vontas J, Field LM: Detection of knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in Anopheles gambiae: a comparison of two new high-throughput assays with existing methods. Malar J. 2007, 6: 111-10.1186/1475-2875-6-111.

World Health Organization: Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes. 2013, Geneva: WHO

Mitchell SN, Stevenson BJ, Muller P, Wilding CS, Egyir-Yawson A, Field LG, Hemingway J, Paine MJI, Ranson H, Donnelly MJ: Identification and validation of a gene causing cross-resistance between insecticide classes in Anopheles gambiae from Ghana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109: 6147-6152. 10.1073/pnas.1203452109.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1995, 57: 289-300.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 - ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001, 25: 402-408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262.

Matambo TS, Abdalla H, Brooke BD, Koekemoer LL, Mnzava A, Hunt RH, Coetzee M: Insecticide resistance in the malarial mosquito Anopheles arabiensis and association with the kdr mutation. Med Vet Entomol. 2007, 21: 97-102. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00671.x.

Himeidan YE, Abdel Muzamil HM, Christopher JM, Ranson H: Extensive permethrin and DDT resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from eastern and central Sudan. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4: 15-10.1186/1756-3305-4-15.

Petrarca V, Nugud AD, Elkarim Ahmmed MA, Haridi AM, Di Deco MA, Coluzzi M: Cytogenetics of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Sudan, with special reference to the An. arabiensis: relationships with East and West African population. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 14: 149-164. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00231.x.

Diabate A, Baldet T, Chandre F, Akogbeto M, Guiguemde TR, Darriet F, Brengues C, Guillet P, Hemingway J, Small GJ, Hougard JM: The role of agricultural use of insecticides in resistance to pyrethroidsin Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 67: 617-622.

Djegbe I, Boussari O, Sidick A, Martin T, Ranson H, Chandre F, Akogbeto M, Corbel V: Dynamics of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Benin: first evidence of the presence of L1014S kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae from West Africa. Malar J. 2011, 10: 261-10.1186/1475-2875-10-261.

Ranson H, Abdalla H, Badolo A, Guelbeogo WM, Kerah-Hinzoumbe C, Yangalbe-Kalnone E, Sagnon N, Simard F, Coetzee M: Insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae: data from the first year of a multi-country study highlight the extent of the problem. Malar J. 2009, 8: 299-10.1186/1475-2875-8-299.

Weetman D, Wilding CS, Steen K, Morgan JC, Simard F, Donnelly MJ: Association mapping of insecticide resistance in wild Anopheles gambiae populations: major variants identified in a low-linkage disequilibrium genome. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e13140-10.1371/journal.pone.0013140.

Brooke BD: Review. kdr: Can a single mutation produce an entire insecticide resistance phenotype?. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102: 524-525. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.001.

Brooke BD, Koekemoer LL: Major effect genes or loose confederations? The development of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Parasit Vectors. 2010, 3: 74-10.1186/1756-3305-3-74.

Muller P, Warr E, Stevenson BJ, Pignatelli PM, Morgan JC, Steven A, Yawson AE, Mitchell SN, Ranson H, Hemingway J, Paine MJI, Donnelly MJ: Field-caught permethrin resistant Anopheles gambiae overexpress CYP6P3, a P450 that metabolizes pyrethroids. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4: 1000286-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000286.

Stevenson BJ, Bibby J, Pignatelli P, Muangnoicharoen S, O'Neill PM, Lian LY, Muller P, Nikou D, Steven A, Hemingway J, Sutcliffe MJ, Paine MJ: Cytochrome P450 6 M2 from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae metabolizes pyrethroids: sequential metabolism of deltamethrin revealed. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011, 41: 492-502. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.02.003.

Vontas JG, Small GJ, Hemingway J: Glutathione S-transferases as antioxidant defence agents confer pyrethroid resistance in Nilaparvata lugens. Biochem J. 2001, 357: 65-72. 10.1042/0264-6021:3570065.

Acknowledgements

HA received financial support from the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (WHO/TDR). The study was supported by grants from the NHLS-Research Trust (LLK) and the South African Research Chair Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation (MC). We would like to thank Chris Jones and Rodolphe Poupardin (LSTM) for assistance with data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HA, CSW, LN and PP were responsible for the field work and laboratory processing of material; LLK, HR and MC designed the project. All authors contributed to the data analysis, drafting the manuscript and all approved the final version.

Electronic supplementary material

13071_2013_1409_MOESM1_ESM.pptx

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Microarray design. Arrows indicate details of labelling: Cy3 → Cy5. N = Wad Medani non exposed controls. R = Wad Medani resistant to permethrin. D = DONG susceptible strain. (PPTX 38 KB)

13071_2013_1409_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Table S1: Summary of L1014F kdr genotypes and allele frequencies in alive and dead An. arabiensis exposed to pyrethroid and DDT from four sentinel sites in central Sudan during six rounds of collections over three years. (DOC 24 KB)

13071_2013_1409_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Additional file 3: Table S2: Summary of significantly differentially expressed probes. The total number of probes following filtering out of probes not significantly > background is also given. (DOCX 11 KB)

13071_2013_1409_MOESM4_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 4: Table S3: List of genes, with corrected p-values and Fold Change, significantly differentially expressed in Wad Medani vs Dongola arrays. (XLSX 179 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdalla, H., Wilding, C.S., Nardini, L. et al. Insecticide resistance in Anopheles arabiensis in Sudan: temporal trends and underlying mechanisms. Parasites Vectors 7, 213 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-213

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-213