Abstract

Background

The nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis is a zoonotic parasite and the most important cause of eosinophilic meningitis worldwide in humans. In Brazil, this disease has been reported in the states of Espírito Santo and Pernambuco. The parasite has been detected in the naturally infected intermediate host, in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco and Santa Catarina. The murid Rattus norvegicus R. rattus were recently reported to be naturally infected in Brazil. In this study, we conducted a two-year investigation of the dissemination pattern of A. cantonensis in R. norvegicus in an urban area of Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, and examined the influence of seasonality, year, host weight and host gender on parasitological parameters of A. cantonensis in rats.

Methods

The study was conducted in an area of Trindade, São Gonçalo municipality, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Prevalence of infected rats, intensity and abundance of A. cantonensis were calculated, and generalized linear models were created and compared to verify the contribution of host gender, host weight, year and seasonality to the variations in A. cantonensis abundance and prevalence in rats.

Results

The prevalence of A. cantonensis infection was stable during the rainy (71%, CI 58.9- 81.6) and dry seasons (71%, CI 57.9-80.8) and was higher in older rats and in females. Seasonality, host weight (used as a proxy of animal age) and gender were all contributing factors to variation in parasite abundance, with females and heavier (older) animals showing larger abundance of parasites, and extreme values of parasite abundance being more frequent in the dry season.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of this parasite throughout the study suggests that its transmission is stable and that conditions are adequate for the spread of the parasite to previously unaffected areas. Dispersion of the parasite to new areas may be mediated by males that tend to have larger dispersal ability, while females may be more important for maintaining the parasite on a local scale due to their higher prevalence and abundance of infection. A multidisciplinary approach considering the ecological distribution of the rats and intermediate hosts, as well as environmental features is required to further understand the dynamics of angiostrongyliasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis is a nematode that, in its adult stage, parasitizes the pulmonary arteries of the synanthropic rodent Rattus norvegicus, the definitive host [1]. Mollusc species act as intermediate hosts and are infected by the first larval stage (L1) eliminated in rodent feces. Three weeks after mollusc infection, the larvae molt to the infective third stage (L3), becoming adult worms after being ingested by rats [2]. Humans become infected mainly by ingesting infected intermediate host or parts of the intermediate host consumed inadvertently when contaminating food is ingested, but may also be infected by consuming paratenic hosts (shrimps, crabs, frogs, planarians, and lizards) [3].

The recent introduction of A. cantonensis to the Americas [4] has resulted in human cases of eosinophilic meningitis throughout the continents [5–10]. In Brazil, this disease has been reported in the states of Espirito Santo, Pernambuco and São Paulo [7, 11, 12], and the natural intermediate host A. fulica has been observed in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco and Santa Catarina [13, 14]. Recently, R. norvegicus and R. rattus have been reported to be naturally infected in Brazil [15, 16].

Although A. cantonensis is currently spreading rapidly throughout the Americas [4], there have not been any studies that have focused on the role of R. norvegicus in parasite transmission; instead, most studies have focused only on the intermediate host [17, 18]. Horizontal studies are important because they allow us to characterize the profile of parasite transmission. In this study, we conducted a two-year investigation of A. cantonensis dissemination pattern in R. norvegicus in an urban area of Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, and examined the influence of seasonality, year, host weight (used as a proxy for host age), and host gender on the prevalence and abundance of A. cantonensis in rats.

Methods

Study area

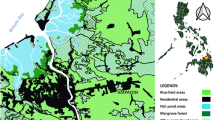

The study was conducted in an urban area of Trindade, São Gonçalo municipality (22°48’26.7”S, 43°00’49.1”W), the second most populous city (~1 million habitants) in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Figure 1). The climate is tropical with recognizable seasons: a rainy season from October to May and a dry season from April to November. The annual average temperature of the region is 25°C, with maximum and minimum temperatures ranging from 38°C to 17°C, respectively. The annual rainfall is 1200 mm (data obtained from Urban Climatological Station from Geosciences lab-LABGEO).

Rodent capture

We established three transects spaced approximately 50 meters apart with 20 trapping stations each along polluted watercourse banks close to human habitats. A trapping station was established every 5 meters and included both a Tomahawk® trap (16 × 5 × 5 inches) and Sherman® trap (3 × 3.75 × 12 inches). The study was conducted every three months from March 2010 to December 2011 and each capture session lasted 4 consecutive days.

Captured rodents were transported to a field laboratory, where they were euthanized in a CO2 chamber, sexed, weighed and necropsied. All animal procedures followed the guidelines for capture, handling and care of mammals of the American Society of Mammalogists [19]. The collection permits for rodents were obtained from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) Ethical Committee on Animal Use (Permit Number: LW 24/10) and the Brazilian government’s Institute for Wildlife and Natural Resources (Permit Number: 24353–1). Biosafety techniques were used during all procedures involving biological samples [20].

Parasitological procedures

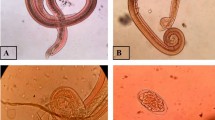

Helminths were collected from the pulmonary arteries and subarachnoid spaces. The organs were separated in Petri dishes and dissected under a stereomicroscope to remove the parasites. The collected worms were washed twice in physiological (0.9%) saline to remove tissue debris and were stored in 70% ethanol. Nematodes were clarified in lactophenol (40% lactophenol, 20% lactic acid, 20% phenol, and water q.s.p. 100 mL) and identified using a Zeiss Standard 20 light microscope. The morphology of the caudal bursa and size of the spicules were used as taxonomic characteristics for species identification according to Maldonado et al. (2010) [13] and Chen (1935) [21].

Data analyses

Prevalences with their Sterne’s exact 95% confidence intervals (CI) [22] and the k index of aggregation were calculated using the program Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 [22]. For that, animals were divided into three age classes according to their weight: juveniles (<100 g), subadults (100–200 g) and adults (>200 g) [23]. A binary logistic regression was used to investigate the influence of season, year, host gender and host weight (used as a proxy of animal age) on the presence/absence of A. cantonensis in rats and a generalized linear model with a negative binomial distribution and log link was performed to verify the contribution of those variables to the observed variation in A. cantonensis abundance in pulmonary arteries of rats. We created models consisting of all combinations and interactions of predictors, as well as additional models containing an interaction between gender and weight plus year and/or season as additional variables. These additional models were included because a priori analyses pointed out the inclusion of the interaction “host gender* host weight” on the pool of best-fitting models (see below). All analyses were performed using PASW Statistics Version 18.0. Models were compared using the Akaike Information Criterion corrected for small sample size (AICc). Models were ranked based on the difference between the best approximating model (model with the lowest AICc) and all others in the set of candidate models (ΔAICc); models with differences within two units of the top model were considered competitive (best-fitting) models with strong empirical support [24]. The relative importance of each predictor (or interaction of predictors) was quantified by calculating relative variable weights (var. weight), which consist on summing the Akaike weights across all the models where the predictor occurs. To better investigate model fit, we calculated the likelihood ratio chi-square test for the best-fitting model of parasite abundance; we also calculated the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic and computed the Nagelkerke R2 for the top model of parasite presence/absence. The wald Chi-Square test was used to check parameter significance in the best-fitting model.

We used the Mann–Whitney U-test and Moses test of extreme reaction in post-hoc analyses to test for differences in the parasite abundance and its range between host gender and seasons, whenever these predictors appeared amongst best-fitting models for parasite abundance. Spearman rank correlation was also used in post-hoc analyses to verify how parasite abundance varied with host weight in males and females. For all significance tests, α = 0.05.

Results

One hundred and fourteen R. norvegicus were captured during the study. Fifty-six rats were collected during the rainy season (4 rats were not weighed) and 58 during the dry season (Table 1).

A total of 861 adult worms were recovered from pulmonary arteries and 82 young worms (L5) in the subarachnoid space found in all age class. The highest parasite burden (42 adult helminths) occurred in an adult female during the dry season. In addition, the distribution of the nematodes was aggregated (k = 2.04).

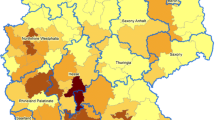

Four models were considered competing models in the analysis of parasite presence/absence in R. norvergicus, but their likelihoods were relatively low (from 0.12 to 0.19; Table 2). Moreover, model fit for the best-fitting model (model 1; Table 2) was also low (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.221; Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic: Chi-squared test = 8.561; df = 8; P = 0.381). Parasite presence/absence was best predicted by host weight (βmodel 1 = 0.006; var. weight = 0.54), host gender (βfemale, model 1 = 1.191; var. weight = 0.50), and year (β2010, model 1 = −0.693; var. weight = 0.50), although “year” was not a significant variable in the top model (Wald Chi-square = 2.20; df = 1; p = 0.138); All the other predictors in the best-fitting model were significant (P < 0.05). The prevalence of A. cantonensis varied from 63% to 87% (Table 3; Figure 2), and tended to be higher in females (78%; CI 65.2-87.2) than in males (59%; CI 46.4-70.1), while the prevalence in juveniles (43% CI 21.3-67.5) tended to be lower than in sub-adults (70% CI 48.9-84.5) and adults (77% CI 65.7-85.0). Prevalence was marginally larger in 2011, but confidence intervals overlapped considerably in this case (79% CI 66.4-88.1 against 64% CI 51.4-74.9; see also Table 3). The interaction between host weight and gender appeared in the third and fourth the best-fitting models for parasite presence/absence (Table 2), but its relative weight was lowest amongst predictors present in the best-fitting models (var. weight =0.40). Prevalence increases with age in both host sexes, but the difference between males and females occurs mostly in juveniles and subadults, with females showing larger prevalences than males. The multivariate analyses using host gender, host weight, year and season as independent variables and A. cantonensis abundance as the dependent variable indicated that two models were considered competitive (models 1 and 2; Table 4). Season, host weight and host gender contributed to variation in parasite abundance (likelihood ratio chi-square for model 1 = 16.03; df = 3; p = 0.001), even though Akaike weights indicated that the likelihood of the best-fitting models were relatively low (AICc weights = 0.40 and 0.15; Table 4). The variable “season” (var. weight = 0.87) appeared amongst the best-fitting models because 90% of the animals with abundance greater or equal than 20 worms (N = 11) were found in the dry season (βdry season,,model 1 = 0.579). Indeed extreme values of parasite abundance were more likely to occur in the dry season (Moses test of extreme reaction: P < 0.001; Figure 3B); parasite abundance, however, did not differ between seasons (P = 0.221). The interaction between host gender and host weight (var. weight = 0.57) appeared amongst the best-fitting models because the relationship between parasite abundance and host weight is stronger in females (βfemales*weight, model 1 = 0.004) than in males (βmales*weight, model 1 = 0.002), and the β value for males was not significant (Wald Chi-Square = 2.971; df = 1; p = 0.085). All the other parameters in the top model were significant (P < 0.05). Post-hoc correlations between parasite abundance and host weight showed that A. cantonensis abundance increases with host weight in both sexes (Rfemales = 0.40, N = 50, P = 0.004; Rmales = 0.30, N = 60, P = 0.002), which would explain why “host weight” (var. weight = 0.37) appeared as a main effect in the second best model (Model 2, Table 4).

Moreover, females had larger parasite abundance (P = 0.044) and extreme values of parasite abundance than males (P = 0.004; Figure 3A). Despite differences in parasite abundance between males and females, “host gender” as a main factor had the lowest relative variable weight amongst predictors in the best-fitting models (0.28).

Discussion

The prevalence of A. cantonensis in R. norvegicus in Rio de Janeiro is relatively high compared to other localities where infected rats have been found [3]. As reviewed by Wang et al. (2008) [3], areas in Cuba and the Dominican Republic (both in the Americas) had a high prevalence of A. cantonensis at 60% (12 infected rodents of 20 collected) and 100% (5 infected rodents in 5 collected), respectively. However, the small sample sizes used in these short-term studies do not allow conclusive results and preclude inference from the helminth infrapopulation structure. In our study, we observed a high and stable prevalence of A. cantonensis over two years, which suggests that transmission is continuously high. Prevalences were marginally larger in 2011, but confidence limits overlapped considerably between years (see also Table 3). It would be interesting, however, to investigate whether A. cantonensis prevalence in R. norvegicus is gradually increasing in the long-term.

The recent settlement of A. cantonensis in the study area of São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro state could partially explain the high prevalence of this parasite. Additionally, the presence of the exotic intermediate host A. fulica in the study area [14], and its recent dispersion to all the 27 federations in Brazil [14, 25, 26] may contribute to the establishment and increase of A. cantonensis transmission to its vertebrate host. However, nothing is known about the population dynamics of the mollusc species present in the study area, although it has been demonstrated that variation in the structure of the intermediate host population plays an important role in the seasonal fluctuations in helminth community parameters in the definitive host [27]. Stability in prevalence may also be caused by the following: (1) a long parasite lifespan in the definitive host and liberation of L1 larvae over long periods of time, which may maintain parasite transmission to the intermediate host even in times of low snail abundance in the environment; (2) the presence of more than one mollusc species that is able to facilitate development to the infective larval stage L3[28]; (3) the lack of factors constraining rat abundance (e.g., constant and high food availability and refuge); and (4) A. cantonensis genetic heterogeneity [29, 30], which may facilitate adaptation to new environments.

The positive relationship between A. cantonensis abundance and rat weight is at least partially associated with higher parasite burdens in older (and heavier) rats. As previously reported [31, 32], this observation is likely due to the longer period of exposure to infection, which is also corroborated by the higher parasite prevalence found in adult rats. Additionally, the relatively weak relationship may also suggest the presence of a regulatory process for parasite density. Indeed, experimental studies demonstrated that rats exposed to A. cantonensis are able to modulate the parasite burden when re-infected [33].

Males have higher levels of testosterone and larger home ranges than females [34, 35], which would potentially increase the probability of acquiring/maintaining an infection [36, 37]. However, females had a higher prevalence and abundance of A. cantonensis than males, and the relationship between parasite abundance and host weight was also stronger in females, which somewhat undermines the hypothesis that males are more frequently exposed to infection because of their larger home ranges and/or testosterone levels. Although male mammals generally harbor more helminth parasites than females [37], the hormonal response of each gender may determine their distinct parasitic profiles [38]. Some studies have demonstrated female-biased parasitism [39–41], suggesting that sex-biased parasitism is a complex phenomenon influenced by hormones other than testosterone [39] and that additional variables in the host-parasite relationship can influence predisposition to infection and parasite burdens. For example, female adolescents seem to locomote more and spend more time exploring aversive areas than males of the same age [42]; if that implies that females explore their home ranges better, then they may be more prone to infection than males. This would explain why prevalences are particularly higher in juvenile and subadult females than males (see Table 3). Notwithstanding, our findings indicate that females may be particularly important for maintaining the parasite at a local scale due to their higher prevalence and abundance of infection and their philopatric behavior, whereas dispersion of the parasite to new areas may be mediated mainly by males that tend to have larger dispersion ability [43, 44].

Although the prevalence of A. cantonensis did not vary between seasons (Table 3), the range of parasite abundance was greater during the dry season. Because the mollusc intermediate hosts are susceptible to desiccation [45], we would expect a lower abundance of snails and a consequently lower prevalence and abundance of A. cantonensis in rats during that season. The presence of a larger number of rats with young larvae of A. cantonensis in the subarachnoid space during the rainy season suggests that infection rates may actually be higher during the wet season. In many natural populations, however, animals show seasonal changes in stress hormones as a response to environmental changes (e.g. food or water shortage) and/or biotic factors (e.g. increased intraspecific competition) [46]. If stress hormones in rats were high during the dry season, then individuals may be less able to modulate parasite infection, which would explain the rats with higher burdens in that season. Nevertheless, there are no studies of seasonal changes in glucocorticoids in tropical mammals to support this hypothesis.

In summary, our results demonstrated that mainly host gender and host age (measured as host weight) contributed to variation in A. cantonensis prevalence, while season, host gender and host weight influenced parasite abundance. However, model fit for both parasite abundance and prevalence was low, which means that additional variables not investigated may be relatively more important for determining parasite abundance/prevalence in the definitive host. For instance, variables directly linked to infection rates and the abundance of the intermediate hosts might better predict R. norvegicus infection rates. Likewise, the host immune system and concomitant infection with other parasites may also be important predictors for the abundance of A. cantonensis in R. norvegicus. To disentangle the influence of these variables on parasite abundance and prevalence, field studies need to be associated with experimental studies.

Conclusions

The stability of A. cantonensis prevalence throughout the duration of this study confirms that this parasite is established in the urban region of São Gonçalo municipality in Rio de Janeiro State and is under adequate conditions for spreading to other areas. We suggest that a multidisciplinary approach that considers ecological aspects (e.g., variation in diet, dispersal ability and home range) of the rats and intermediate hosts, as well as environmental features is required to further understand the dynamic of several zoonoses, including angiostrongyliasis [47]. These studies are therefore essential for the implementation of surveillance and control strategies to reduce the risk of angiostrongyliasis among local residents and to limit the occurrence of new foci.

References

Acha PN, Szyfres B: Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Man and Animals. Volume 3. 2003, Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, Scientific and Tech. Publications, 3

Wang QP, Wu ZD, Wei J, Owen RL, Lun ZR: Human Angiostrongylus cantonensis: an update. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012, 35: 389-395.

Wang Q, Lai D, Zhu X, Chen X, Lun Z: Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008, 8: 621-630. 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70229-9. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70229-9

Maldonado AJ, Simões R, Thiengo S: Angiostrongyliasis in the Americas. Zoonosis. Volume 1. Edited by: Morales-Lorenzo J. 2012, InTech, 303-320. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/zoonosis/angiostrongyliasis-in-the-americas, 1

Pascual J, Bouli R, Aguiar H: Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis in Cuba, caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Amer J Trop Med Hyg. 1981, 30: 960-962.

Dorta-Contreras A, Padilla-Docal B, Moreira J, Robles L, Aroca J, Fernando Alarcón F, Bu-Coifiu- Fanego R: Neuroimmunological findings of Angiostrongylus cantonensis meningitis in ecuadorian patients. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2011, 69: 466-469. 10.1590/S0004-282X2011000400011.

Lima A, Mesquita S, Santos S, Aquino E, Rosa L, Duarte F, Teixeira A, Costa Z, Ferreira M: Alicata disease: neuroinfestation by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2009, 67: 1093-1096. 10.1590/S0004-282X2009000600025.

Barrow K, St Rose A, Lindo J: Eosinophilic meningitis: is Angiostrongylus cantonensis endmic in Jamaica?. West Indian Med J. 1996, 45: 70-71.

New D, Little M, Cross J: Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection from eating raw snails. New Eng J Med. 1995, 332: 1105-1106.

Aguiar P, Morera P, Pascual J: First record of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Cuba. Amer J Trop Med Hyg. 1981, 30: 963-965.

Espirito-santo MC, Pinto PLS, Mota DJG, Gryschik RCB: The first case of Angiostrongylus cantonensis eosinophilic meningitis diagonesd in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop. 2013, 55: 129-132. 10.1590/S0036-46652013000200012. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652013000200012

Caldeira R, Mendonça C, Gouveia C, Lenzi H, Graeff-Teixeira C, Lima WS, Mota EM, Pecora IL, Medeiros AMZ, Carvalho OS: First record of molluscs naturally infected with Angiostrongylus cantonensis (chen, 1935) (nematoda: metastrongyloidea) in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007, 102: 887-889. 10.1590/S0074-02762007000700018.

Thiengo S, Maldonado A, Mota E, Torres E, Caldeira R, Carvalho OS, Oliveira AP, Simões RO, Fernandez MA, Lanfredi RM: The giant African snail Achatina fulica as natural intermediate host of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Pernambuco, northeast Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010, 115: 194-199. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.01.005.

Maldonado A, Simões R, Oliveira A, Motta E, Fernandez M, Pereira ZM, Monteiro SS, Torres EJ, Thiengo SC: First report of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Achatina fulica (mollusca: gastropoda) from Southeast and South regions of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010, 105: 938-941.

Moreira VL, Giese EG, Melo FT, Simões RO, Thiengo SC, Maldonado A, Santos JN: Endemic angiostrongyliasis in Brazilian Amazon: natural parasitism of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Rattus rattus and R. norvegicus, and sympatric giant African land snails, Achatina fulica. Acta Trop. 2012, 125: 90-97.

Simões RO, Monteiro FA, Sanchez E, Thiengo SC, Garcia JS, Costa-Neto SF, Luque JL, Maldonado A: Endemic angiostrongyliasis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17: 1331-1333. 10.3201/eid1707.101822.

Ibrahim MM: Prevalence and intensity of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in freshwater snails in relation to some ecological and biological factors. Parasite. 2007, 14: 61-70. 10.1051/parasite/2007141061.

Mahajan RK, Almeida AJ, Sengupta SR, Renapurkar DM: Seasonal intensity of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the intermediate host, Laevicaulis alte. Int J Parasitol. 1992, 22: 669-671. 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90017-F.

Gannon WL, Sikes RS: Guidelines of the American society of mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. J Mammal. 2011, 92: 235-253. 10.1644/10-MAMM-F-355.1.

Lemos ERS, D’andrea PS: Trabalho com Animais Silvestres. Biossegurança, Informação e Conceitos, Textos Básicos. Edited by: Martins EV, Martins AS, Silva FHAL, Lopes MCM, Moreno MLV, Silva PCT. 2006, Rio de Janeiro: FIOCRUZ, 273-288. 1

Chen HT: A new pulmonary nematode of rats, Pulmonema cantonensis ng. nsp from Canton. Ann Parasitol. 1935, 13: 312-317.

Reiczigel J, Rózsa L: Quantitative parasitology 3.0. Budapest. 2005

Webster JP, Macdonald DW: Parasites of wild brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) on UH farms. Parasitology. 1995, 11: 247-255.

Burnham KP, Anderson DR: Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. 2002, New York: Springer

Thiengo SC, Simões RO, Fernandez MA, Maldonado A: Angiostrongylus cantonensis and rat lungworm disease in Brazil. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013, 72: 18-22.

Thiengo SC, Faraco FA, Salgado NC, Cowie R, Fernandez MA: Rapid spread of an invasive snail in South America: the giant African snail, Achatina fulica in Brazil. Biol Invasions. 2007, 9: 693-702. 10.1007/s10530-006-9069-6.

Maldonado A, Gentile R, Fernandes-Moraes CC, D’Andrea PS, Lanfredi RM, Rey L: Helminth communities of Nectomys squamipes naturally infected by the exotic trematode schistosoma mansoni in southeastern Brazil. J Helminthol. 2006, 80: 369-375. 10.1017/JOH2006366.

Carvalho Odos S, Scholte RG, Mendonça CL, Passos LK, Caldeira RL: Angiostrongylus cantonensis (nematode: metastrongyloidea) in molluscs from harbour areas in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012, 107: 740-746. 10.1590/S0074-02762012000600006.

Monte TC, Simões RO, Oliveira AP, Novaes CF, Thiengo SC, Silva AJ, Estrela PC, Maldonado A: Phylogenetic relationship of the Brazilian isolates of the rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis (nematoda: metastrongylidae) employing mitochondrial COI gene sequence data. Parasit Vectors. 2012, 6: 248-256.

Tokiwa T, Harunari T, Tanikawa T, Komatsu N, Koizumi N, Tung K-C, Suzuki J, Kadosaka T, Takada N, Kumagai T, Akao N, Ohta N: Phylogenetic relationships of rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, isolated from different geographical regions revealed widespread multiple lineages. Parasitol Int. 2012, 61: 431-436. 10.1016/j.parint.2012.02.005.

Abu-Madi MA, Lewis JW, Mickail M, Et-Nagger ME, Behnke JM: Monospecific helminth and arthropod infections in an urban area population of brown rats from Doha, Qatar. J Helminthol. 2001, 75: 313-320.

Abu-Madi MA, Behnke JM, Mikhail M, Lewis JW, Alkaabi ML: Parasite populations in the brown rat Rattus norvegicus from Doha, Qatar between years: the effect of host age, sex and density. J Helminthol. 2005, 79: 105-111. 10.1079/JOH2005274.

Au ACS, Ko RC: Changes in worm burden, haematological and serological response in rats after single and multiple Angiostrongulus cantonensis infections. Z Parasitenkd. 1979, 58: 233-242. 10.1007/BF00933930.

Lambert MS, Quy RJ, Smith RH, Cowan DP: The effect of habitat management on home‒range size and survival of rural Norway rat populations. J Appl Ecol. 2008, 2008 (45): 1753-1761.

Zuk M, McKean KA: Sex differences in parasite infections: patterns and processes. Int J Parasitol. 1996, 26: 1009-1023. 10.1016/S0020-7519(96)00086-0.

Schalk G, Forbes R: Male biases in parasitism of study type, host age and parasite taxon. Oikos. 1997, 78: 67-74. 10.2307/3545801.

Innes J: Advances in New Zealand mammalogy 1990–2000: European rats. J R SocNew Zealand. 2001, 31: 111-125. 10.1080/03014223.2001.9517642.

Poulin R: Sexual inequalities in helminth infections: a cost of being a male?. Amer Nat. 1996, 147: 287-295. 10.1086/285851.

Schuurs A, Verheul HAM: Effects of gender and sex steroids on the immune response. J Ster Biochem Mol Biol. 1990, 35: 157-172. 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90270-3.

Morales-Montor J, Chavarria A, De León MA, Del Castillo LI, Escobedo EG, Sánchez EN, Vargas JA, Hernández-Flores M, Romo-González T, Larralde C: Host gender in parasitic infections of mammals: an evaluation of the female host supremacy paradigm. J Parasitol. 2004, 90: 531-546. 10.1645/GE-113R3.

Krasnov BR, Morand S, Hawlena H, Khokhlova IS, Shenbrot GI: Sex-biased parasitism, seasonality and sexual size dimorphism in desert rodents. Oecologia. 2005, 146: 209-217. 10.1007/s00442-005-0189-y.

Lynn DA, Brown GR: The ontogeny of exploratory behaviour in male and female adolescent rats (Rattus norvegicus). Dev Psychol. 2009, 51: 513-520. 10.1002/dev.20386.

Calhoun JB: The Ecology and Sociology of the Norway rat. 1963, Bethesda, Maryland: U.S: Department of Health, Education and Welfare

Taylor KD: Range of movement and activity of common rats (Rattus norvegicus) on agricultural land. J App Ecol. 1978, 15: 663-677. 10.2307/2402767.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica: Vigilância e Controle de Moluscos de Importância Epidemiológica, Diretrizes Técnicas: Programa de Vigilância e Controle da Esquistossomose. 2007, Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde, 2

Reeder DM, Kramer KM: Stress in free-ranging mammals: integrating physiology, ecology, and natural history. J Mammal. 2005, 86: 225-235. 10.1644/BHE-003.1.

Himsworth CG, Parsons KL, Jardine C, Patrick DM: Rats, Cities, people, and pathogens: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of literature regarding the ecology of rat-associated zoonoses in urban centers. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 13: 1-11. 10.1089/vbz.2012.1002. doi:10.1089/vbz.2012.1195

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all that helped with the field work; the staff of CEADE for making a space available for our field laboratory; Secretary of Health of São Gonçalo; Heloisa Diniz of Imaging Service-FIOCRUZ and Geosciences Lab from Geography department (UERJ/FFP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the work: ROS, AMJ and JLL. Performed the work: ROS and JSG. Analyzed the data: ROS, NO, AMJ and JLL. Revised the manuscript for important intellectual content: AMJ, NO, JSG and JLL. Wrote the paper: ROS. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Simões, R.O., Júnior, A.M., Olifiers, N. et al. A longitudinal study of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in an urban population of Rattus norvegicus in Brazil: the influences of seasonality and host features on the pattern of infection. Parasites Vectors 7, 100 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-100

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-100