Abstract

Background

In the Eastern and Upper Midwestern regions of North America, Ixodes scapularis (L.) is the most abundant tick species encountered by humans and the primary vector of B. burgdorferi, whereas in the southeastern region Amblyomma americanum (Say) is the most abundant tick species encountered by humans but cannot transmit B. burgdorferi. Surveys of Borreliae in ticks have been conducted in the southeastern United States and often these surveys identify B. lonestari as the primary Borrelia species, surveys have not included Arkansas ticks, canines, or white-tailed deer and B. lonestari is not considered pathogenic. The objective of this study was to identify Borrelia species within Arkansas by screening ticks (n = 2123), canines (n = 173), and white-tailed deer (n = 228) to determine the identity and locations of Borreliae endemic to Arkansas using PCR amplification of the flagellin (flaB) gene.

Methods

Field collected ticks from canines and from hunter-killed white-tailed were identified to species and life stage. After which, ticks and their hosts were screened for the presence of Borrelia using PCR to amplify the flaB gene. A subset of the positive samples was confirmed with bidirectional sequencing.

Results

In total 53 (21.2%) white-tailed deer, ten (6%) canines, and 583 (27.5%) Ixodid ticks (252 Ixodes scapularis, 161 A. americanum, 88 Rhipicephalus sanguineus, 50 Amblyomma maculatum, 19 Dermacentor variabilis, and 13 unidentified Amblyomma species) produced a Borrelia flaB amplicon. Of the positive ticks, 324 (22.7%) were collected from canines (151 A. americanum, 78 R. sanguineus, 43 I. scapularis, 26 A. maculatum, 18 D. variabilis, and 8 Amblyomma species) and 259 (37.2%) were collected from white-tailed deer (209 I. scapularis, 24 A. maculatum, 10 A. americanum, 10 R. sanguineus, 1 D. variabilis, and 5 Amblyomma species). None of the larvae were PCR positive. A majority of the flaB amplicons were homologous with B. lonestari sequences: 281 of the 296 sequenced ticks, 3 canines, and 27 deer. Only 22 deer, 7 canines, and 15 tick flaB amplicons (12 I. scapularis, 2 A. maculatum, and 1 Amblyomma species) were homologous with B. burgdorferi sequences.

Conclusions

Data from this study identified multiple Borreliae genotypes in Arkansas ticks, canines and deer including B. burgdorferi and B. lonestari; however, B. lonestari was significantly more prevalent in the tick population than B. burgdorferi. Results from this study suggest that the majority of tick-borne diseases in Arkansas are not B. burgdorferi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the Eastern and Upper Midwestern regions of North America, Ixodes scapularis (L.) is the most abundant tick species encountered by humans and the primary vector of Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease), whereas in the southeastern region Amblyomma americanum (Say) is the most abundant tick species encountered by humans but it cannot transmit B. burgdorferi[1, 2]. Since its first description in the 1970s, Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vector-borne disease in the northern hemisphere [3]. However, in some areas of the world Lyme borreliosis may be caused by Borrelia genotypes other than B. burgdorferi and includes a range of symptoms and pathologies [3, 4]. In the southern United States B. lonestari is associated with Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness (STARI) or Masters disease [5, 6]. This bacteria is common throughout the southeast and has been identified primarily in A. americanum; however, the etiology of B. lonestari remains undetermined [7–15] and recent reports indicate B. lonestari may not be pathogenic [16].

Health professionals often question cases of Lyme disease from the southeastern United States because symptoms may be confused with other tick-borne illnesses and not all patients produce the erythema migrans or bull’s eye rash used for diagnosis [15, 17]. Additionally, these cases are rarely fatal, but can cause cardiac, neurological and joint problems [17]. However, the potential vectors (I. scapularis), pathogens (B. burgdorferi) and hosts (Peromyscus species) are all present in the south [17]. In Georgia, B. burgdorferi was isolated and characterized from field collected I. scapularis and cotton mice (Peromyscus gossypinus); and these field isolates were transmitted via I. scapularis to hamsters (Cricetidae) and mice (Muridae) [1]. Field collected I. scapularis from Alabama could acquire, maintain, and transmit B. burgdorferi[18] and field collected ticks and rodents from the southern U.S. were positive for B. burgdorferi[1, 19–22]. Previously in Arkansas, ticks and reservoir species were screened for Borrelia in nine northeast Arkansas counties using indirect fluorescence antibody (IFA), both I. scapularis and A. americanum were identified as potential vectors, and deer mice (Peromyscus spp.) and marsh rice rats (Oryzomys palustris Harlan) as potential reservoir hosts [23]. Although the environment is suitable for Borrelia transmission [17], many researchers and physicians do not believe the southern U.S. is at risk for Borrelia related diseases [2, 4, 15]. The exact cause for the reduced incidence for Lyme disease in the southern United States is unknown, but hypotheses include the abundance of other tick species in the area, the habitat, host dynamics, and tick genetics [2, 24].

Previous research indicates that B. burgdorferi IFA positive canines geographically associated with I. scapularis infested deer, increase the likelihood of B. burgdorferi transmission to humans because the nymphs that feed on the deer may also feed on canines and their owners [25, 26]. Recent Arkansas tick studies identified five tick species infesting canines and white-tailed deer with A. americanum infesting canines and I. scapularis primarily infesting white-tailed deer [27]. A population genetic study of I. scapularis based on the 16 S mtDNA identified both the American and Southern lineages (formerly known as I. scapularis and I. dammini) on canines and white-tailed deer [28], which is a concern because the American I. scapularis lineage is more likely than the Southern I. scapularis lineage to transmit Lyme disease [29]. The objective of this study was to identify Borrelia species within Arkansas ticks, canines, and white-tailed deer to determine the identity and locations of Borreliae endemic to Arkansas using PCR amplification of the flagellin (flaB) gene. The CDC defines an endemic county as “endemic for Lyme disease if there are at least two confirmed human cases that were acquired in that county or there are established populations of I. scapularis infected with B. burgdorferi”[30].

Methods

Tick, canine, and white-tailed deer collections

This project used the collections reported in Trout and Steelman [27]. Briefly, ticks were collected from canines (March 2006 to November 2007) and white-tailed deer (Oct. 2007 – Jan. 2008) and stored in 80% ethanol until visual identification of species and life stage [31–33]. Additionally, a small volume of canine or white-tailed deer blood (0.5-1 cc) was obtained from each host and stored on a FTA card (FTA ® Indicating Micro Card, Whatman International Ltd, Maidstone, England) in an envelope labeled with collection information. FTA cards were stored at room temperature until DNA extraction. All FTA cards, all ticks from canines, and at least one specimen of each tick species from each white-tailed deer were subjected to further analyses.

Tick DNA extraction and detection for Borrelia species

To minimize DNA contamination, DNA extractions and PCR were conducted in different laboratories and reagents and equipment were dedicated to each procedure. Tick identification and extractions were conducted in the Veterinary Entomology Laboratory (VELUA) and PCR reactions were conducted in the Insect Genetics Laboratory (IGLUA) at the University of Arkansas. During each PCR, at least one blank reagent to detect contamination (negative control) and an appropriate positive control ensured PCR reagents and conditions were used. PCR and reaction product analyses were performed on the ticks according to the protocols of Trout et al.[28]. After tick identification to species, each specimen was dried on a paper towel to allow the residual ethanol to evaporate and was then cut longitudinally and half of the tick was subjected to the Qiagen Dneasy Insect Protocol (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Extracted DNA from half of the tick was stored at −20°C until further analyses. The remaining tick half was stored at −20°C for additional analysis or morphological confirmation as required. To evaluate the tick DNA, each sample was first assessed by PCR with Ixodidae specific mitochondrial primers (16 S + 2/16 S-1) using previously described cycling parameters [34]. If the mitochondrial marker amplified, then the tick was subjected to a genus specific flaB PCR to identify the presence of Borrelia DNA [6, 35].

Host DNA extraction and detection for Borrelia species

Each canine and white-tailed deer FTA card was screened in duplicate to determine the presence of Borrelia DNA. The FTA card was cut into halves, where half of the card remained at VELUA for an initial screening and the other half was sent to the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Ft. Worth (UNTHSC) for verification screening. Each FTA card half was removed from its envelope and a 1.2 mm disc was punched from the card using a sterilized Harris Micro Punch and the paper disc was washed for DNA extraction according to the Whatman protocol (Harris MicroPunch®, Whatman International Ltd, Maidstone, England). After the punch had dried at room temperature, it was subjected to PCR analyses. To ensure DNA detection from FTA punches were not inhibited in any manner, FTA punches were assessed for PCR amplification of host cytochrome b genes [36]. As with the ticks, canines and white-tailed deer specimens were screened for Borrelia species by PCR in a genus specific manner [6, 35].

Statistical analyses

Summary statistics and relative abundance of each tick species were calculated to determine overall trends within the population using JMP (α = 0.05) [37]. Fisher’s exact tests and two-tailed T-tests were performed in Excel 2007 to determine if the species of tick or tick host had any effect on the probability that the tick would be PCR positive for Borrelia[38]. Since spatial and temporal sampling of ticks and hosts were different (e.g., ticks from white-tailed deer were collected only in the fall) and this sampling structure may affect findings, comparisons across and among cohorts were not conducted.

Sequence identification of Borrelia species

PCR products, from flaB positive samples, were sent to UNTHSC for DNA sequence analysis. The PCR reaction products were hydrolyzed with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH) and sequence determination was performed using a BigDYE Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA) followed by capillary electrophoresis on a ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA) using the method of Williamson et al. [39]. Sequences were edited, aligned, and analyzed with Sequencher 4.7 (Gene Codes, Corporation, Ann Arbor MI) and compared with sequences in GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD).

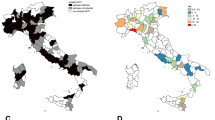

Spatial identification of Borrelia species

Canine and deer collection data along with their corresponding tick collections and Borrelia DNA presence/absence data were georeferenced into ArcMap 9.0 (ESRI Redlands, CA USA) and projected to the NAD 1983 UTM Zone 15 N of the GCS North American 1983 Geographic coordinate system. Boolean operations and symbology were used to identify locations with PCR positive ticks and hosts. The resulting Boolean map was overlaid on an existing county map of Arkansas [40].

Results

Identification of Borrelia DNA in the tick population

A total of 2123 ticks were included in this study and represented five tick species; I. scapularis (33%), A. americanum (31%), R. sanguineus (16 %), D. variabilis (9%), and A. maculatum (8%). An additional 3% were Amblyomma ticks that could not be identified to species because the tick specimens were damaged. The tick population was comprised of each life stage, but most were adults (83%) and more were collected from domesticated canines (67%) than from hunter-killed white-tailed deer (33%). Overall, 583 of the 2123 (27.5%) ticks tested by PCR produced an amplicon for the Borrelia flaB gene (Table 1). The prevalence of flaB amplicons for each tick species were 36.4 % (252/692) I. scapularis, 27.9% (50/179) A. maculatum, 25.8% (88/341) R. sanguineus, 24.5% (161/657) A. americanum, and 10.3% (19/184) D. variabilis. Fifty percent of the 583 flaB amplicons from PCR positive ticks were sequenced, representing approximately one fourth of the specimens from each tick species (Table 2). DNA sequences produced from the tick flaB amplicons represented multiple genotypes of Borrelia. These sequences align with B. burgdorferi strain B31 (AB035617), OK-strain HS-2 (FJ871032), Borrelia lonestari Clone Scc26 (DQ100451), isolate MO2002-V1 (AY850063), isolate TX076 (EF689742), strain NC/MD (AF273670), and clone AA115 (AY654945) (Figure 1). The majority (136/296) of flaB sequences matched B. lonestari strain NC/MD (AF273670) which was amplified from all five tick species. Locations of all Borrelia isolated from ixodid ticks collected from Arkansas canines and white-tailed deer during 2007 were mapped because B. burgdorferi ticks were few (Figure 2).

Polar tree layout of the phylogenetic relationship of the Borrelia flagellin B ( flaB ) gene fragment (330 bp) amplified from ticks collected from Arkansas canines and white-tailed deer, and host blood samplesa. Those specimens aligning with B. burgdorferi are highlighted in grayb. a The different tick species are abbreviated A. americanum (Aa), A. maculatum (Am), D. variabilis (Dv), I. scapularis (Is), and R. sangineus (Rs). Ticks from canines (c), ticks from deer (d), and blood samples (Canine or Deer) are also represented. bThe different Borrelia species are abbreviated as BL for B. lonestari and BB for B. burgdorferi

Identification of Borrelia DNA in canines and their ticks

Of the 173 canines and their 1427 ticks subjected to the flaB PCR, 5.8% (n = 10) and 22.7% (n = 324) were positive respectively. All ten positive canine flaB amplicons were sequenced and six samples were homologous to B. burgdorferi IP2 (AY345236), two were homolgous to B. lonestari NC/MD (AF273670), one was homologous to B. lonestari fragments MO2002-V1 (AY850063), and one was homologous to strain B. burgdorferi OK HS-2 (FJ871032) (Table 2). Contingency tests revealed that the number of flaB positive and negative ticks were significantly different based on tick species (×2 = 31.9; df = 5; P < 0.0001) such that I. scapularis (35.5%) had the highest flaB positive rate. The most frequently encountered tick on canines was A. americanum and 23.8% (151/634) were flaB PCR positive. Of the 173 canines, 87 canines did not have a positive tick, 27 canines had one positive tick, and 59 canines had more than one positive tick. Of the 59 canines with more than one positive tick, 18 canines had multiple specimens of the same species that were positive, 13 canines had specimens of two separate tick species positive, and two canines had specimens of three separate tick species PCR positive.

In canine collected ticks, the B. lonestari strain NC/MD (AF273670) was also the most common amplicon and amplified in nymphs, males, and females. Positive ticks were identified primarily in northwest Arkansas where many of the canines were collected (Figure 2A). Ticks from B. burgdorferi positive canines did not generate B. burgdorferi sequences. Instead these ticks were either negative for flaB or produced flaB positive amplicons that were homologous with B. lonestari.

Identification of Borrelia DNA in white-tailed deer and their ticks

Of the 250 white-tailed deer and the 696 ticks subjected to the flaB PCR, 19.6% (n = 49) and 37.2% (n = 259) were positive for flaB. Of the 49 white-tailed deer flaB amplicons, 24 amplicons were homologous to B. lonestari NC/MD (AF273670), 21 amplicons were homologous to B. burgdorferi OK HS-2 (FJ871032), 3 amplicons were homolgous to B. lonestari MO2002-V1 (AY850063), and one amplicon was homolgous to B. burgdorferi IP2 (AY345236) (Table 2). Contingency tests revealed that the number of flaB positive and negative ticks were not significantly different based on tick species (X2 = 3.96; df = 5; P = 0.556). flaB prevalence rates in ticks from white-tailed deer was 62.5% (5/8) in unknown Amblyomma, 41.7% (10/24) in R. sanguineus, 43.5% (10/23) in A. americanum, 37.5% (24/64) in A. maculatum, 36.6 % (209/571) in I. scapularis, and 16.7% (1/6) in D. variabilis. A majority of white-tailed deer did not have a positive tick (n = 91), but 70 white-tailed deer had more than one PCR positive tick of which 24 deer had more than one flaB positive tick species and one deer had three different tick species flaB positive. Fragments amplified from all five deer-collected tick species were most similar to the B. lonestari sequence AY850063. Positive ticks were identified throughout Arkansas (Figure 2B).

Discussion

Borreliae were identified in field collected ticks, canines, and white-tailed deer throughout the state suggesting the bacteria (as a family) are endemic in Arkansas. Of interest was the diversity of Borrelia genotypes identified from the variety of different field collections (Figure 1, Table 2). Five different B. lonestari genotypes and three different B. burgdorferi genotypes were identified in Arkansas. None of the genotypes appeared to be more common in one tick species or host; however, B. burgdorferi genotypes were only identified in ticks collected from deer - the significance of this finding remains to be determined. Specifically, B. burgdorferi genotypes were amplified only from twelve I. scapularis, two A. maculatum, and an Amblyomma tick that was too damaged for the species to be determined. Only one I. scapularis nymph was homologous with B. burgdorferi, consequently there is insufficient data to consider the area endemic for Lyme disease. This damaged Amblyomma nymph was collected in Washington County of northwest Arkansas. B. burgdorferi transmission by A. maculatum needs additional attention and previous studies with A. americanum have indicated that A. americanum cannot transmit B. burgdorferi[1, 2]. Due to the low prevalence of B. burgdorferi in nymphal ticks, Arkansas should not be considered a Lyme disease endemic area [30]. B. lonestari NC/MD was the most common sequence amplified (45.6%) and it is homologous to the sequence previously isolated from a patient’s skin with Lyme-like symptoms [41] suggesting this genotype is the most common Borrelia in Arkansas. In 2007, four Arkansas counties reported human cases of Lyme disease (Benton, Carroll, Washington, Crawford, and Saline Co.). Ticks collected from these counties in this study primarily produced amplicons homologous to B. lonestari, and a few ticks produced amplicons homologous to B. burgdorferi. If these human cases of Lyme disease are ‘real’ then they are most likely either rare, acquired from a different location, or are false positives. Collections of field collected ticks near the site of transmission (e.g., where the tick attached to the human) would answer these questions. Data presented here corroborate with Texas collected ticks identified with B. lonestari DNA in A. americanum A. cajennense, A. maculatum, D. variabilis, I. scapularis, and R. sanguineus and relatively few samples of B. burgdorferi DNA (AE000783) [39] and with B. lonestari in Arkansas white-tailed deer serum [26].

We documented Borrelia in five tick species infesting domesticated canines and white-tailed deer; consequently, Borreliae are likely endemic in Arkansas and in the southeastern U.S. by a more diverse tick repertoire than previously thought. Identifying Borrelia in ticks indicates that field collected ticks have fed on infected animals at some point in their life cycle and identifying Borrelia in canines and white-tailed deer indicates that infected ticks have transmitted Borrelia to these hosts. We observed a trend for ticks collected from canines to be positive with B. lonestari whereas ticks from deer could be positive with either B. lonestari or B. burgdorferi. This may be related to the species of tick collected on each host and the sampling periods, as canines were primarily infested with A. americanum and collected year round whereas white-tailed deer were primarily infested with I. scapularis and collected in the fall. Also, ticks feeding on white-tailed deer may actually be feeding on hosts that are incompetent reservoirs of Lyme disease [42]. Additional evidence is required to assert the potential for each role in transmission. Past research has indicated that several tick species are not active vectors of B. burgdorferi (e.g., transmission through salivary glands) [18, 20], but additional research should isolate Borrelias from the study area and confirm these tick species are not passive vectors (e.g., transmission studies in a suitable animal model). Additionally, often ticks are misidentified and physicians do not think “beyond Lyme disease” to diagnose the patient properly [2]. Other tick-borne diseases transmitted in Arkansas include rickettsia spotted fevers [32, 43] and Ehrlichiosis [13, 39], perhaps the cases of Lyme disease reported in 2007 were actually misdiagnosed.

Monitoring tick populations on canines could provide reliable early detection of tick-borne disease outbreaks [44]. Monitoring field populations of ticks for B. burgdorferi and other tick-borne diseases is essential to minimize transmission and maximize management. Recent landscape changes in Arkansas are expanding urban environments into deer habitats [45, 46]. Previously, this pattern of urban development into previous deer habitats in Lyme Connecticut led to the increased diagnoses of Lyme disease in the northeastern United States [47]; similar reports have indicated B. burgdorferi emerged independently in the Midwest and eastern United States [48–50].

Additional research into the involvement of Borrelia spp. in the southeastern zoonotic cycle (e.g., abundance of tick/host infection, reservoir maintenance, vector competency) should be conducted in order to determine the life cycle and etiology of the various Borreliae detected in this survey and what roles, if any, they may play relative to subsequent borreliosis observed in humans. Future work should also evaluate the interaction of A. americanum carrying B. lonestari, A. maculatum carrying B. burgdorferi, and I. scapularis carrying B. burgdorferi and what effect, if any, this might have on the pathogenicity of the Borreliae, as both tick species have been identified simultaneously infesting the same host [27, 51]. It is possible that there are multiple interactions occurring between tick species (e.g., species competition for host), the variety of hosts (e.g., Ixodid ticks feed on three different hosts), and the different Borreliae (infesting both the tick and the host), which warrants additional research.

Conclusions

Data from this study indicate multiple Borrelia genotypes are endemic to Arkansas because flaB was amplified from ticks, canines, and white-tailed deer, but the exact role each genotype plays in transmission and epidemiology remains undetermined. There were significantly more amplicons of B. lonestari than B. burgdorferi present suggesting that the majority of tick-borne diseases in Arkansas are not B. burgdorferi.

Abbreviations

- flaB:

-

flagellin gene

- IFA:

-

indirect fluorescence antibody

- IGLUA:

-

Insect Genetics Laboratory at the University of Arkansas

- STARI:

-

Southern tick associated rash illness

- UNTHSC:

-

University of North Texas Health Science Center in Ft. Worth

- VELUA:

-

Veterinary Entomology Laboratory at the University of Arkansas.

References

Oliver JH, Owsley MR, Hutcheson HJ, James AM, Chen C, Irby WS, Dotson EM, McLain DK: Conspecificity of the ticks Ixodes scapularis and I. dammini (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1993, 30: 54-63.

Stromodahl EY, Hickling GJ: Beyond Lyme: etiology of tick-borne human diseases with emphasis on the southeastern United States. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2012, in press

Dennis DT, Piesman JF: Overview of tick-borne infections of humans. Tick-borne Diseases of Humans. Edited by: Goodman JL, Dennis DT, Sonenshine DE. 2005, ASM Press, Washington, D.C, 3-11.

Bacon RM, Kiersten MS, Kugeler J, Mead PS: Surveillance for Lyme Disease—United States, 1992–2006. MMWR. 2008, 57 (Suppl 10): 1-9.

Armstrong PM, Rich SM, Smith RD, Hart DL, Spielman A, Telford SR: A new Borrelia infecting lone star ticks. Lancet. 1996, 347: 67-68.

Barbour AG, Maupin GO, Teltow GJ, Carter CJ, Piesman J: Identification of an uncultivatable Borrelia species in the hard tick Amblyomma americanum: possible agent of a Lyme disease-like illness. J Infect Dis. 1996, 173: 403-9. 10.1093/infdis/173.2.403.

Burkot TR, Mullen GR, Anderson R, Schneider BS, Happ CM, Zeidner NS: Borrelia lonestari DNA in Adult Amblyomma americanum Ticks, Alabama. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001, 7: 471-473.

Stegall-Faulk T, Clark DC, Wright SM: Detection of Borrelia lonestari in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) from Tennessee. J Med Entomol. 2003, 40: 100-102. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.1.100.

Stromdahl EY, Williamson PC, Kollars TM, Evans SR, Barry RK, Vince MA, Dobbs NA: Evidence of Borrelia lonestari DNA in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) removed from humans. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41: 5557-62. 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5557-5562.2003.

Clark K: Borrelia species in host-seeking ticks and small mammals in northern Florida. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 5076-5086. 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5076-5086.2004.

Varela-Stokes AS: Transmission of bacterial agents from lone star ticks to white-tailed deer. J Medical Entomol. 2007, 44: 478-483. 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[478:TOBAFL]2.0.CO;2.

Taft SC, Miller MK, Wright SM: Distribution of Borreliae among ticks collected from eastern states. Vector Borne Zoonot Dis. 2005, 5: 383-389. 10.1089/vbz.2005.5.383.

Mixson TR, Campbell SR, Gill JS, Ginsberg HS, Reichard MV, Schulze TL, Dasch GA: Prevalence of Ehrlichia, Borrelia, and Rickettsial Agents in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) Collected from nine states. J Med Entomol. 2006, 43: 1261-1268. 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[1261:POEBAR]2.0.CO;2.

Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Healy SP, Roegner VE, Meddis M, Jahn MB, Guthrie DL: Relative abundance and prevalence of selected Borrelia infections in Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) from publicly owned lands in Monmouth County, New Jersey. J Med Entomol. 2006, 43: 1269-1275. 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[1269:RAAPOS]2.0.CO;2.

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control: Lyme Disease. Division of Vector Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases. 2007,http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/lyme/ld_transmission.htm,

Vaughn MF, Sloane PD, Knierim K, Varkey D, Pilgad MA, Johnson BJB: Practice based research network partnership with CDC to acquire clinical specimens to study the etiology of Southern Tick-Associated rash illness (STARI). JABFM. 2010, 23: 720-727. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.100098.

Goddard J: What’s going on with Lyme disease in the South?. Inf Med. 2001, 18: 132-133.

Piesman J, Sinsky RJ: Ability of Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) to acquire, maintain, and transmit Lyme disease spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi). J Med Entomol. 1998, 25: 336-339.

Magnarelli LA, Oliver JH, Hutcheson HJ, Boone JL, Anderson JF: Antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in rodents in the eastern and southern United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1992, 30: 1449-1452.

Sanders FH, Oliver JH: Evaluation of Ixodes scapularis, Amblyomma americanum, and Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) from Georgia as Vectors of a Florida Strain of the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Med Entomol. 1995, 32: 402-406.

Durden LA, McLean RG, Oliver JH, Ubico SR, James AM: Ticks, Lyme disease spriochetes, trypanosomes, and antibody to encephalitis viruses in wild birds from coastal Georgia and South Carolina. J Parasitol. 1997, 83: 1178-1182. 10.2307/3284382.

Weller SJ, Baldridge GD, Munderloh UG, Noda H, Simser J, Kurtti TJ: Phylogenetic placement of rickettsiae from the ticks Amblyomma americanum and Ixodes scapularis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998, 36: 1305-1317.

Simpson KK, Hinck LW: The prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete, in ticks and rodents in northeast Arkansas. Proc Arkansas Academy of Sci. 1993, 47: 110-115.

Diuk-Wasser MS, Hoen AG, Cislo P, Brinkerhoff R, Hamer SA, Rowland M, Cortinas R, Vourc’h G, Melton F, Hickling GJ, Tsao JI, Bunikis J, Barbour AG, Kitron U, Piesman J, Fish D: Human risk of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, in eastern United States. Am Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012, 86: 320-327. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0395.

Daniels TJ, Fish D, Levine JF, Greco MA, Eaton AT, Padgett PJ, LaPointe DA: Canine exposure to Borrelia burgdorferi and prevalence of Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae) on deer as a measure of Lyme disease risk in the northeastern United States. J Med Entomol. 1993, 30: 171-178.

Murdock JH, Yabsley MJ, Little SE, Chandrashekar R, O'Connor TP, Caudell JN, Huffman JE, Langenberg JA, Hollamby S: Distribution of antibodies reactive to Borrelia lonestari and Borrelia burgdorferi in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) populations in the eastern United States. Vector borne and Zoonotic Dis. 2009, 9: 729-736. 10.1089/vbz.2008.0144.

Trout RT, Steelman CD: Ticks parasitizing canines and deer in Arkansas. J Entomol Sci. 2010, 45: 140-148.

Trout RT, Steelman CD, Szalanski AL: Population Genetics and Phylogeography of Ixodes scapularis from Canines and Deer in Arkansas. Southwestern Entomol. 2009, 34: 273-287. 10.3958/059.034.0308.

Qiu WG: Geographic uniformity of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) and its shared history with tick vector (Ixodes scapularis) in the northeastern United States. Genetics. 2002, 160: 833-849.

(CDC) Centers for Disease Control: Lyme Disease Division of Vector Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases. 2012,http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/faq/index.html#endemic,

Arthur DR: Ticks and Disease. 1961, Row, Peterson and Company, Evanston, IL

Lancaster JL, Patrick JK: Rocky mountain spotted fever in northwest Arkansas. J Arkansas Med Soc. 1977, 74: 156-158.

Goddard J, Norment BR: A guide to the ticks of Mississippi. 1985, Mississippi Agric For Expnt Stat Bull, Mississippi, 935-

Black WC, Piesman J: Phylogeny of hard- and soft- tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16 S rDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994, 91: 10034-10038. 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10034.

Bacon RM, Gilmore RD, Quintana M, Piesman J, Johnson BJB: DNA evidence of Borrelia lonestari in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) in Southeast Missouri. J Med Entomol. 2003, 40: 590-592. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.590.

Gilbert C, Ropiquet A, Hassanin A: Mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies of Cervidae (Mammalia, Ruminantia): Systematics, morphology, and biogeography. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006, 40: 101-117. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.017.

Sall J, Creighton L, Lehman A: JMP Start Statistics: A guide to statistics an data analysis using JMP and JMP IN Software. 2005, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 3

Dodge M, Stinson C: What’s new in Microsoft Office Excel 2007. Microsoft Office Excel 2007 inside out. 2007, Microsoft Press, Indianapolis, IN

Williamson PC, Billingsley PM, Teltow GJ, Seals JP, Turnbough MA, Atkinson SF: Borrelia, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia spp. in ticks removed from persons, Texas, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010, 16: 441-446.

Arkansas State Land Information Board: Natural color Select 1-Foot county Mosaic. Digital Orthrophoto Quadrangles, Color Infrared and Natural Color. 2006, AR Counties, Little Rock, Arkansas,http://www.geostor.arkansas.gov/G6/Home.html?id=bbf7f1801f53d2c3a3fcf719bef46f84,

James AM, Liveris D, Wormser GP, Schwartz I, Montecalvo MA, Johnson MJB: Borrelia lonestari infection after a bite by an Amblyomma americanum tick. J Infect Dis. 2001, 183: 1810-1814. 10.1086/320721.

Telford SR, Mather TN, Moore SI, Wilson ML, Spielman A: Incompetence of deer as reservoirs of the Lyme disease spirochete. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988, 39: 105-109.

Kardatzke JT, Neidhardt K, Dzuban DP, Sanchez JL, Azad AF: Cluster of tick-borne infections at Fort Chaffee, AR: Rickettsiae and Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodid ticks. J Med Entomol. 1992, 29: 669-672.

Rhea SK, Glickman SW, Waller A, Ising A, Maillard JM, Lund EM, Glickman LT: Evaluation of routinely collected veterinary and human health data for surveillance of human tick-borne diseases in North Carolina. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2011, 11: 9-14. 10.1089/vbz.2009.0255.

DeFries RS, Foley JA, Asner GP: Land-use choices: balancing human needs and ecosystem function. Front Ecol Environ. 2004, 2: 249-257. 10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0249:LCBHNA]2.0.CO;2.

Lepczyk CA, Hammer RB, Stewart SI, Radeloff VC: Spatiotemporal dynamics of housing growth hotspots in the North Central U.S. from 1940 to 2000. Landscape Ecol. 2007, 22: 939-952. 10.1007/s10980-006-9066-2.

Spielman A: The emergence of Lyme disease and human babesiosis in a changing environment. Ann New York Acad of Sci. 2006, 740: 146-156.

Pinger RR, Timmons L, Karris K: Spread of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in Indiana: collections of adults in 1991–1994 and description of a Borrelia burgdorferi infected populations. J Med Entomol. 1996, 33: 852-855.

Diuk-Wasser MA, Gatewood AG, Cortinas MR, Yaremych-Hamer S, Tsao J, Kitron U, Hickling G, Brownstein JS, Walker E, Piesman J, Fish D: Spatiotemporal patterns of host-seeking Ixodes scapularis nymphs (Acari: Ixodidae) in the United States. J Med Entomol. 2006, 43: 166-176. 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)043[0166:SPOHIS]2.0.CO;2.

Hoen AG, Margos G, Bent SJ, Diuk-Wasser MA, Barbour A, Kurtenbach K, Fish D: Phylogeography of Borrelia burgdorferi in the eastern United States reflects multiple independent Lyme disease emergence events. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009, 106: 15013-15018. 10.1073/pnas.0903810106.

Koch HG: Seasonal incidence and attachment sites of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on domestic dogs in southeastern Oklahoma and northwestern Arkansas. J Med Entomol. 1982, 19: 293-298.

Acknowledgments

We thank veterinarians with the Arkansas Veterinarian Society, Cory Gray with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, and the personnel involved with each association for collecting the tick samples from the various hosts. Special thanks to the Department of Forensic and Investigative Genetics at the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Ft. Worth Texas for conducting the sequence analyses and screening the FTA cards for Borrelia. We would also like to acknowledge the Department of Entomology at the University of Arkansas for additional support with this project. This research was supported in part by the University of Arkansas, Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare we have no competing interests with the work presented in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

RTF, CDS, and ALS conceived the study and designed the experiments. PMB and PCW conducted the work in Texas, and RTF conducted the work in Arkansas. RTF, KLK, PMB, and PCW analyzed the results. RTF and PCW wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fryxell, R.T.T., Steelman, C.D., Szalanski, A.L. et al. Survey of Borreliae in ticks, canines, and white-tailed deer from Arkansas, U.S.A.. Parasites Vectors 5, 139 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-139

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-139