Abstract

Background

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic drug used as a blood-sparing technique in many surgical specialties. The principal objective of our meta-analysis was to review randomized, controlled trials (RCT) comparing total blood loss and the number of patients receiving allogeneic blood transfusions with and without the use of TXA for knee (TKA) and hip (THA) arthroplasty.

Methods

Studies were included if patients underwent primary unilateral TKA or THA; the study involved the comparison of a TXA treatment group to a control group who received either a placebo or no treatment at all; outcome measures included total blood loss TBL, number of patients receiving allogeneic blood transfusions, and/or incidence of thromboembolic complications; the study was a published or unpublished RCT from 1995 – July 2012.

Results

Data were tested for publication bias and statistical heterogeneity. Combined weighted mean differences in blood loss favoured TXA over control for TKA and THA patients respectively [ −1.149 (p < 0.001; 95% CI −1.298, -1.000), -0.504 (p < 0.001; 95% CI, -0.672, -0.336)]. Combined odds ratios favoured fewer patients requiring allogeneic transfusions for TKA and THA with the use of TXA respectively [0.145 (p < 0.001; 95% CI, 0.094, 0.223), 0.327 (p < 0.001; 95% CI, 0.208, 0.515)]. Combined odds ratios indicated no increased incidence of DVT with TXA use in TKA and THA respectively [1.030 (p = 0.946; 95% CI, 0.439, 2.420), 1.070 (p = 0.895; 95% CI, 0.393, 2.911)].

Conclusions

TXA should be considered for routine use in primary knee and hip arthroplasty to decrease blood loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of total knee (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) is increasing and both are associated with considerable blood loss[1–9] thereby increasing a patient’s risk of transfusion[5, 9, 10]. Blood loss often leads to significant postoperative anemia[11] predisposing to an increased risk for cardiopulmonary events, transfusion reactions, and increased health care costs[5, 12]. Allogeneic transfusions may also increase the patient’s risk for post-operative infection[3, 10, 13, 14].

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic amino acid[2–4, 6, 9, 12, 14–16] which competitively blocks the lysine binding sites on plasminogen and thereby slows the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin[2, 3, 5–8, 10, 12, 14–20]. TXA may be administered intra-venous (IV) or topically in the surgical wound. TXA has been reported to reduce blood loss and be cost effective in many areas of orthopedic surgery, such as spinal surgery[11] as well as knee and hip arthroplasty[15, 17–19]. One significant concern with TXA however, is the possibility that it, as well as other antifibrinolytics, could increase the risk of developing thromboembolic complications such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

We performed a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials (RCT) to assess the efficacy of TXA in TKA and THA for the outcomes of total blood loss (TBL), the number of patients receiving allogeneic transfusions and the incidence of DVT.

We hypothesized that the use of TXA in both TKA and THA would significantly reduce blood loss and the number of patients receiving allogeneic transfusions without an increased incidence of DVT.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if: 1) patients underwent primary unilateral TKA or THA; 2) the study involved the comparison of a TXA treatment group to a control group who received either a placebo or no treatment at all; 3) outcome measures included TBL, number of patients receiving allogeneic blood transfusions, and/or incidence of thromboembolic complications; 4) the study was a published or unpublished RCT from 1995 – July 2012; 5) the procedure involved was not described as ‘minimally invasive’ or ‘less invasive’. Both English and non-English studies were included in the meta-analysis. Data on cost-effectiveness was not included in many research papers and thus was not used as an eligibility criterion.

Study identification

Two independent reviewers completed a systematic computerized search of online data-bases including Pubmed, Ovid MEDLINE and EMBASE. The key words used for the search included: tranexamic acid OR TXA AND total knee replacement OR total hip replacement OR total knee arthroplasty OR total hip arthroplasty OR TKA OR THA OR TKR OR THR. We also searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and http://www.Clinicaltrials.gov. After reviewing the title of the study we retrieved the abstract if we felt it was appropriate. We independently reviewed these abstracts and chose those studies that were potentially relevant. Bibliographies of each study included were reviewed for any further studies. Further, we searched the archives of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (2001–2011), Knee Society (2001–2011), Canadian Orthopedic Association (2003–2011), British Orthopedic Association (2002–2011) meetings for other potential studies.

Assessment of study quality

All studies were reviewed by two independent reviewers using the Jadad Score, a scale of 0 (very poor) to 5 (rigorous) was used to assess the methodological strength of a clinical trial[21]. Any conflicts were resolved by consensus. Studies with a Jadad score of 1 were considered poor, scores of 2 were considered adequate and a score of 3 or higher was considered as high quality.

Data collection

The following data were collected from all manuscripts for both the treatment group (TXA) as well as the control group: patient demographics, number of patients, dose of TXA, method of TXA administration, type of control (saline, non-TXA), TBL and/or number of patients receiving allogeneic transfusions, transfusion criteria, DVT screening method, thromboprophylaxis used, incidence of DVT and/or thromboembolic complications, as well as cost effectiveness.

Statistical analysis

Knee and hip replacement data were analyzed separately for our outcomes of interest: total surgical blood loss and the number of patients requiring allogeneic blood transfusions. In both cases, data were aggregated using a random-effects model and the meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 2.0 (Engelwood, NJ).

The summary statistic used for the continuous outcome of mean blood loss was the weighted mean difference (WMD). The WMD refers to the ratio of the differences between the means of the treatment and control groups divided by the standard deviation. In our study, a negative WMD favored the treatment group (TXA) and a positive WMD favored the control group. Some studies did not provide standard deviation (SD) values so, whenever possible, these values were cited from a previous systematic review of antifibrinolytic therapies by Kagoma et al.[22] which used pooled and estimated SD values where studies had not provided them. In some cases, if a CI was provided, the SD was calculated using the following formula where U refers to the upper limit of the CI, μ to the mean, s to the SD and n to the number of study participants in each group (TXC, control).

The summary statistic used for the outcomes: the number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusions as well as the incidence of DVT, was the odds ratio (OR). In this case, the OR referred to the odds of a patient requiring a blood transfusion in the treatment group divided by the odds of a patient requiring a blood transfusion in the control group; similarly, the odds of a patient having a DVT in the treatment group divided by the odds of a patient having a DVT in the control group. An OR value of less than one indicates that fewer patients in the TXA group required allogeneic blood transfusions, or developed a DVT, than in the control group. An OR value of greater than one indicates that more patients in the TXA group required allogeneic blood transfusions, or developed a DVT, than in the control group. We used two strategies to assess statistical heterogeneity between studies for both of our outcome measures. First, we used the methods of Hedges and Olkin to test for significance and homogeneity[23]. A p value < 0.1 was considered suggestive of statistical heterogeneity as these tests are traditionally underpowered.

The heterogeneity between studies was also assessed using the I2 statistic. The I2 statistic is a measure of the percentage of variation in the data that is as a result of heterogeneity as opposed to chance. I2 values of 0-25% are considered low, 25-75% are considered moderate and over 75% are considered high heterogeneity. Possible sources of heterogeneity which we noted prior to performing our study were: 1) the method of measuring/calculating blood loss; 2) the dose of TXA and method of administration; 3) the transfusion criteria 4) patient diagnosis (osteoarthritis versus inflammatory arthritis).

In addition, two funnel-plots were constructed for the outcomes of TBL and the number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusions, in patients undergoing TKA, to assess publication bias, the tendency of studies with a negative result to not be published. The more asymmetric the funnel plot, the more potential bias.

Results

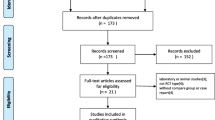

Using our search terms, a total of 420 references were identified. Three hundred and eighty-two were excluded after applying our eligibility criteria from their titles and/or abstracts, including exclusion of duplicates. Of the remaining 38 studies, three were excluded for lack of a control group and one was not randomized. Therefore, a total of 33 studies were included. All eligible studies were English-language.

Out of the 33 studies, one was triple-blind[24], 24 were double-blind[2, 4–6, 8, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18],[20, 25–37], three were single-blind[19, 38, 39], and in five studies the blinding was unclear[3, 40–44]. Additionally, 21 studies had a Jadad score greater than three[2, 4–6, 11, 12, 14, 17–19, 24–27, 31],[33–38] indicating they were of high quality. Ten studies[2, 3, 6, 18, 24–26, 31, 35, 36] used computer generated methods of randomization, one study used random number tables/lists[37] and 12 studies used sealed envelopes for allocation concealment[5, 6, 11, 12, 17, 24, 25, 27],[29, 38, 40, 41]. In eight studies the randomization was performed by a person/pharmacist/resident not involved in the study or the care of patients[4, 5, 11, 17, 27, 29, 34, 35]. In eight studies the method of randomization was unclear[8, 20, 28, 31, 33, 39, 42, 43]. Study characteristics as well as patient characteristics can be seen in Tables 1,2,3 and4.

The methods of TXA administration varied between studies. TXA was administered intravenously in 29 studies[2–6, 8, 12, 14, 17–20, 25–36, 38–42], intra-articularly in three studies[24, 37, 43], orally in one study[35] and topically in one study[11].

Figures 1 and2 represent funnel plots examining for potential publication bias between studies involving patients undergoing TKA. Figure 1 reports the weighted mean difference (WMD) of blood loss as a measure of the treatment effect (TXA). Figure 2 reports the logs OR of the numbers of patients requiring allogeneic transfusions as a measure of the treatment effect. Figure 1 demonstrates only minimal asymmetry and a few outliers, indicating mild publication bias. Figure 2 demonstrates moderate asymmetry, also indicating mild publication bias.

For TBL, the combined WMD for patients undergoing TKA was found to be −1.149 (p < 0.001; 95% CI −1.298, -1.000) (Figure 3). This indicates that for TKA patients, blood loss was less in the TXA groups in comparison to the control group at a statistically significant level. There was a high level of statistical heterogeneity between studies (p = 0.000, I2 = 85.710). We performed a sensitivity analysis here to explore causes of heterogeneity. Pooling data from only those studies administering TXA IV and calculating TBL based on the weight change of surgical swabs and drapes as well as the drain volume, demonstrated a statistically significant benefit of TXA over control; WMD = −1.706 (p < .001 95% CI −1.949,-1.463).

The combined WMD value for TBL in THA was −0.504 (p < 0.001; 95% CI, -0.672, -0.336) (Figure 4). This indicates that, for THA patients, blood loss was less in the TXA groups in comparison to the control group at a statistically significant level. There was a moderate level of heterogeneity between studies (p = 0.006, I2 = 58.000).

The combined OR for the number of patients receiving allogeneic blood transfusions for patients undergoing TKA was 0.145 (p < 0.001; 95% CI, 0.094, 0.223) (Figure 5). This indicates that, for TKA patients, the number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusions was less in the TXA groups in comparison to the control group at a statistically significant level. There was no heterogeneity between studies (p =0.801, I2 = 0.000).

The combined OR for the number of patients receiving allogeneic blood transfusions for patients undergoing THA was 0.327 (p < 0.001; 95% CI, 0.208, 0.515) (Figure 6). This indicates that, for THA patients, the number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusions was less in the TXA groups in comparison to the control group at a statistically significant level. There was moderate heterogeneity between studies (p = 0.135, I2 = 34.089).

The combined OR for the number of patients who developed a DVT for patients undergoing TKA was 1.030 (p = 0.946; 95% CI, 0.439, 2.420) (Figure 7). This indicates that, for TKA patients, there was no increase incidence of DVT associated with the use of TXA. There was no heterogeneity between studies (p =0.615, I2 = 0.000).

The combined OR for the number of patients who developed a DVT for patients undergoing THA was 1.070 (p = 0.895; 95% CI, 0.393, 2.911) (Figure 8). This indicates that, for THA patients, there was no increase incidence of DVT associated with the use of TXA. There was no heterogeneity between studies (p =0.677, I2 = 0.000).

In regards to complications, overall, a total of 30 DVT, three pulmonary embolisms (PE), one myocardial infarction (patient had a history of ischaemic heart disease[27]), three wound infections, nine wound hematomas, one chest infection were reported in the TXA groups. In the control groups a total of 20 DVT, four PE, five wound infections and six wound hematomas were reported.

Discussion

The results of our meta-analysis demonstrate a statistically significant benefit for TXA in reducing TBL and the number of patients receiving allogeneic transfusions in TKA and THA. We found the effect was even greater for TKA patients. There were also minimal differences in the incidence of thromboembolic complications with the use of TXA in our review.

In addition to TXA, other antifibrinolytic drugs, such as aprotinin, epsilon aminocaproic acid (EACA) , and fibrin spray have been used to decrease surgical blood loss[22]. Aprotinin however may cause allergic reactions[13, 31], thrombosis, nephrotoxicity as well as spongiform encephalopathy[13] and has not been shown to be cost-effective[31]. Aminocaproic acid has been shown be more costly and yet less effective than TXA[13] (TXA is 7–10 times as potent[28]). TXA has also been shown to be less expensive when compared to fibrin sealants and just as effective[11, 15].

In a fiscally constrained health care system, the cost benefit analysis of a therapeutic intervention is critical. Benoni et al.[17] and Good et al.[18] described total cost savings of 11, 354 SEK and £1100 respectively for patients undergoing TKA using TXA. Molloy et al. also noted an incremental cost per patient in their TXA group of only £4, compared to £380 in their fibrin spray group[19]. In their THA cohort, Benoni et al.[33] described a total savings of £625 per patient using TXA. Some have estimated a yearly savings of $65,000.00 (Can) for 1000 primary arthroplasties with routine TXA use[15]. The role of TXA use in routine primary arthroplasty appears cost effective but should be an outcome measure routinely studied in RCTs.

A single adequately powered RCT to detect a 0.5SD effect size difference in TBL (assuming 80% power and an alpha error rate of 5%) would require 63 patients per arm. By this calculation, all of the individual studies included in our meta-analysis were underpowered, suggesting that those concluding no difference between groups committed a type II beta error. This highlights the strength and importance of meta-analysis techniques as our study reviewed 33 manuscripts including a total of 1,957 patients, thereby increasing the power of our conclusion.

Additional meta-analyses and systematic reviews analyzing the efficacy of TXA in TKA and THA have been published. Zufferey et al.[44] and Kagoma et al.[22] examined the efficacy of TXA, aprontinin and EACA. However, data were pooled for orthopaedic procedures and antifibrinolytic treatment respectively. Zhang et al.[45] and Yang et al.[46] published meta-analyses analyzing blood loss, transfusion rates and rates of DVT with TXA in TKA. Data from bilateral TKAs were included, potentially leading the significant heterogeneity in mean differences of total blood loss. Cid and Lozano[47] examined transfusion rates in TKA with TXA however only included nine studies. Ho and Ismail[48] studied the effect of TXA with respect to transfusion rates. The majority of studies were for TKAs and sample size was fewer than 10 studies. Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses of TXA in TKA and THA were published in 2011 by Alshryda et al.[49] and Sukeik et al.[50] respectively. These reviews investigated the effects of TXA in TKA and THA with respect to total blood loss, post-operative blood loss, DVT and transfusion rate. Both, however, included fewer than ten studies in their analysis of total blood loss. Furthermore, Alshryda et al. included fewer than 15 studies in their analysis of allogeneic transfusions, and Sukeik et al. included fewer than 10. Despite their differences, all reviews came to conclusions analogous to our own.

There were several strengths of our review and meta-analysis. First, we performed exhaustive searches of the English and non-English languages literature to limit publication bias and pooled data from 33 manuscripts, including only RCTs. Second, many of our studies had Jadad scores of greater than three, indicating that most articles were of high quality.

Limitations

Our paper also has limitations. We used the Jadad score for assessing the quality of the individual studies. We recognize that this tool has limitations. It has been described as simplistic as it takes into account a limited number of variables and does not take into consideration bias as a result of allocation concealment[51]. In our study, we cannot exclude the presence of additional unpublished trials that showed a negative or an equivocal difference between the intervention and control groups. We note as well some limitations related to heterogeneity. We found moderate heterogeneity between TKA studies reporting blood loss however we performed a sensitivity analysis here to explore the cause of this heterogeneity. Despite differences among the studies, our findings suggest that across the various methods of measuring TBL or routes of administration, TXA lead to decreased blood loss as compared with alternative approaches. We have presented the I2 value for each outcome measure analyzed. Please note we present the data despite some with high heterogeneity and suggest that the reader use caution in interpreting the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we find that TXA leads to a statistically significant reduction in TBL and fewer patients requiring allogeneic transfusions, with no apparent increased risk of thromboembolic complications. Incomplete reporting of complications prevented us from pooling of this data and such larger trials are still needed to confirm the safety of TXA use in routine primary TKA and THA.

Abbreviations

- TXA:

-

Tranexamic acid

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- TBL:

-

Total blood loss

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- DVT:

-

Deep vein thrombosis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean difference.

References

Jones CA, Voaklander DC, Johnston DWC, Suarez-Alamazor ME: The effect of age on pain, function, and quality of life after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med. 2001, 161: 454-60. 10.1001/archinte.161.3.454.

Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K: Use of Tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999, 83: 596-601. 10.1093/bja/83.4.596.

Veien M, Sørensen JV, Madsen F, Juelsgaard P: Tranexamic acid given intraoperatively reduces blood loss after total knee replacement: a randomized controlled study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002, 46: 1206-1211. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.461007.x.

Kakar PN, Gupta N, Govil P, Shah V: Efficacy and safety of Tranexamic acid in control of bleeding following TKR: a randomized clinical trial. Indian J Anesth. 2009, 53: 667-671.

Orpen NM, Little C, Walker G, Crawfurd EJP: Tranexamic acid reduces early post-operative blood loss after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of 29 patients. Knee. 2006, 13: 106-10. 10.1016/j.knee.2005.11.001.

Álvarez JC, Santiveri FX, Ramos I, Vela E, Puig L, Escolano F: Tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusion in total knee arthroplasty even when a blood conservation program is applied. Transfusion. 2008, 48: 519-525. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01564.x.

Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, Merino I, Segur JM, Pereira A, Salazar F, Cid J, Lozano L, Mazzara R, Macule F: Effectiveness and safety of Tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008, 95: 39-44. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01045.x.

Kazemi SM, Mosaffa F, Eajazi A, Kaffashi M: The effect of Tranexamic acid on reducing blood loss in cementless total hip arthroplasty under epidural anesthesia. Thorofare. 2010, 33: 17-

Dhillon MS, Bali K, Prabhakar S: Tranexamic acid for control of blood loss in bilateral total knee replacement in a single stage. Indian J Orthop. 2011, 45: 148-152. 10.4103/0019-5413.77135.

Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P: Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011, 469: 2874-2880. 10.1007/s11999-011-1874-2.

Wong J, Abrishami A, El Beheiry H, Mahomed NN, Roderick Davey J, Gandhi R, Syed KA, Muhammad Ovais Hasan S, De Silva Y, Chung F: Topical application of tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss in total knee Arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of efficacy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010, 92: 2503-2513. 10.2106/JBJS.I.01518.

Hiippala ST, Strid LJ, Wennerstrand MI, Vesa J, Arvela V, Niemelä H, Mäntylä SK, Kuisma RI, Ylinen JE: Tranexamic acid radically decreases blood loss and transfusions associated with total knee Arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1997, 84: 839-844.

Ortega-Andreu M, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo R, Gómez-Barrena E: Blood loss control with two doses of tranexamic acid in a multimodal protocol for total knee Arthroplasty. Open Orthop J. 2011, 5: 44-48. 10.2174/1874325001105010044.

Garneti N, Field J: Bone bleeding during total hip arthroplasty after administration of tranexamic acid. J Arthroplasty. 2004, 19: 488-92. 10.1016/j.arth.2003.12.073.

Ralley FE, Berta D, Binns V, Howard J, Naudie DDR: One intraoperative dose of tranexamic acid for patients having primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010, 468: 1905-11. 10.1007/s11999-009-1217-8.

MacGillivray RG, Tarabichi SB, Hawari MF, Raoof NT: Tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss after bilateral total knee arthroplasty, a prospective, randomized double blind study. J Arthroplasty. 2011, 26: 24-8.

Benoni G, Fredin H: Fibrinolytic inhibition with Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after knee arthroplasty – a prospective, randomised, double-blind study of 86 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996, 78: 434-40.

Good L, Peterson E, Lisander B: Tranexamic acid decreases external blood loss but not hidden blood loss in total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth. 2003, 90: 596-9. 10.1093/bja/aeg111.

Molloy DO, Archbold HAP, Ogonda L, McConway J, Wilson RK, Beverland DE: Comparison of topical fibrin spray and tranexamic acid on blood loss after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surge [Br]. 2007, 89-B: 306-309.

Malhotra R, Kumar V, Garg B: The use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg. 2011, 21: 101-104. 10.1007/s00590-010-0671-z.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds JM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials : Is blinding necessary?. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-2. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Kagoma YK, Crowther MA, Douketis K, Bhandari M, Eikelbloom J, Lim W: Use of antifibrinolytic therapy to reduce transfusion in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery: A systematic review of randomized trials. Thromb Res. 2009, 123: 687-696. 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.09.015.

Hedges LV, Olkin I: Statistical methods for meta-analysis. 1985, Orlando: Academic Press, 108-138.

Sa-Ngasoongsong P, Channoom T, Kawinwonggowit V, Woratanarat P, Chanplakorn O, Wibulpolrasert B, Wongsak S, Udomsubpayakul U, Wechmongkolgorn S, Lekpittaya N: Postoperative blood loss reduction in computer-assisted surgery total knee replacement by low dose intra-articular tranexamic acid injection together with 2-hour clamp drain: a prospective triple-blinded randomized controlled trial. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2011, 3: e12-

Husted H, Blønd L, Sonne-Holme S, Holm G, Jacobsen TW, Gebuhr P: Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood-transfusions in primary total Hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003, 74: 665-669. 10.1080/00016470310018171.

Johansson T, Petterson L, Lisander B: Tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty saves blood and money: a randomized, double-blind study in 100 patients. Acta Orthop. 2005, 76: 314-319.

Hiippala S, Strid L, Wennerstrang M, Arvela V, Mäntylä S, Ylinen J, Niemelä H: Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) reduces perioperative blood loss associated with total knee Arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1995, 74: 534-537. 10.1093/bja/74.5.534.

Ekbäck G, Axelsson K, Ryttberg L, Edlund B, Kjellberg J, Weckström J, Carlsson O, Schött U: Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in total hip replacement surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000, 91: 1124-1130.

Benoni G, Lethagen S, Nilsson P, Fredin H: Tranexamic acid, given at the end of the operation, does not reduce postoperative blood loss in hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000, 71: 250-254. 10.1080/000164700317411834.

Niskanen RO, Korkala OL: Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in cemented hip arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind study of 39 patients with osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2005, 76: 829-832. 10.1080/17453670510045444.

Camarasa MA, Ollé G, Serra-Prat M, Martín A, Sánchez M, Ricós P, Pérez A, Opisso L: Efficacy of aminocaproic, tranexamic acids in the control of bleeding during total knee replacement: a randomized clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2006, 96: 576-582. 10.1093/bja/ael057.

Claeys MA, Vermeersch N, Haentjens P: Reduction of blood loss with Tranexamic acid in primary total Hip replacement surgery. Acta Chir Belg. 2007, 107: 397-401.

Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P: Blood conservation with Tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. A randomized, double-blind study in 40 primary operations. Act Ortho Scand. 2001, 72: 442-448. 10.1080/000164701753532754.

Lemay E, Guay J, Côté C, Roy A: Tranexamic acid reduces the need for allogenic red blood cell transfusions in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Can J Anesth. 2004, 51: 31-37. 10.1007/BF03018543.

Zohar E, Ellis M, Ifrach N, Stern A, Sapir O, Fredman B: The postoperative-blood sparing efficiency of oral versus intravenous Tranexamic acid after total knee replacement. Anesth Analg. 2004, 99: 1679-1683.

Ellis MH, Fredman B, Zohar E, Ifrach N, Jedeikin R: The effect of tourniquet application, Tranexamic acid, and desmopressin on the procoagulant and fibrinolytic systems during total knee replacement. J Clin Anesth. 2001, 13: 509-513. 10.1016/S0952-8180(01)00319-1.

Roy SP, Tanki UF, Butta A, Jain SK, Nagi OM: Efficacy of Intra-articular Tranexamic acid in blood loss reduction following primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012, [Epub ahead of print]

McConnell JS, Shewale S, Munro NA, Shah K, Deakin AH, Kinninmonth AW: Reduction of blood loss in primary hip arthroplasty with Tranexamic acid or fibrin spray. Acta Orethopaedica. 2011, 82: 660-663. 10.3109/17453674.2011.623568.

Imai N, Dohmae Y, Suda K, Miyasaka D, Ito T, Endo N: Tranexamic acid for reduction of blood loss during total Hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012, [Epub ahead of print]

Yamasaki S, Masuhara K, Fuki T: Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss after cementless total hip arthroplasty—prospective randomized study in 40 cases. Int Orthop (SICOT). 2004, 28: 69-73. 10.1007/s00264-003-0511-4.

Tanaka N, Sakahashi H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S: Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001, 83-B: 702-5.

Engel JM, Hohaus T, Ruwoldt R, Menges T, Jurgensen I, Hempelmann G: Regional hemostatic status and blood requirements after total knee arthroplasty with and without Tranexamic acid or aprontinin. Anesth Analg. 2001, 92: 775-780. 10.1213/00000539-200103000-00041.

Ishida K, Tsumura N, Kitagawa A, Hamamura S, Fukuda K, Dogaki Y, Kubo S, Matsumoto T, Matsushita T, Chin T, Iguchi T, Kurosaka M, Kuroda R: Intra-articular injection of Tranexamic acid reduces not only blood loss but also knee joint swelling after total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2011, 35: 1639-1645. 10.1007/s00264-010-1205-3.

Zufferey P, Merguiol F, Laporte S, Decousus H, Mismetti P, Auboyer C, Samama CM, Molliex S: Do antifibrinolytics reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in orthropedic surgery?. Anesthesiology. 2006, 105: 1034-1046. 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00026.

Zhang H, Chen J, Chen F, Que W: The effect of Tranexamic acid on blood loss and use of blood products in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011, [Epub ahead of print]

Yang Z, Chen W, Wu L: Effectiveness and safety of Tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. JBJS Am. 2012, [Epub ahead of print]

Cid J, Lozano M: Tranexamic acid reduces allogeneic Red cell transfusions in patient undergoing total knee arthroplasty: results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion. 2005, 45: 1302-1307. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00204.x.

Ho KM, Ismail H: Use of intravenous Tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total Hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003, 31: 529-537.

Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM: Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBJS Br. 2011, 93-B: 1577-1585.

Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of Tranexamic acid in total Hip replacement. JBJS Br. 2011, 930B: 39-46.

Berger VW, Alperson SY: A General Framework for the Evaluation of Clinical Trial Quality. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2009, 4: 79-88. 10.2174/157488709788186021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

There are no competing interests for any author.

Authors’ contributions

RG conceived and designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript. HE performed data acquisition, drafted the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. SM performed data acquisition and revised the manuscript. NM participated in the study design and coordination and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gandhi, R., Evans, H.M., Mahomed, S.R. et al. Tranexamic acid and the reduction of blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes 6, 184 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-184

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-184