Abstract

Background

Behçet’s Disease (BD) is characterized by a relapsing-remitting course, with symptoms of varying severity across almost all organ systems. There is a diverse array of therapeutic options with no universally accepted treatment regime, and it is thus important that clinical practice is evidence-based. We reviewed all currently available literature describing management of BD, and investigated whether evidence-based practice is possible for all disease manifestations, and assessed the range of therapeutic options tested.

Methods

We conducted an internet search of all literature describing management of BD up to August 2013, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. We recorded treatment options investigated and disease manifestations reported as primary and secondary study outcomes. Quality of data was assessed according to the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) hierarchy of evidence.

Results

Whilst there is much literature describing treatment of ocular and mucocutaneous disease, there is little to guide management of rheumatoid, cardiovascular and neurological disease. This broadly reflects the prevalence of disease manifestations of BD, but not the severity. Biologic therapies are the most commonly investigated intervention. The proportion of SIGN-1 graded studies is declining, and there are no SIGN-1 graded studies investigating neurological or gastrointestinal manifestations of BD.

Conclusions

This is the first study to investigate trends in published literature for management of BD over time. It identifies neurological, cardiovascular and gastro-intestinal disease as particular areas of unmet need and suggests that overall quality of evidence is declining. Future research should be designed to address these areas of insufficiency to facilitate evidence-based practice in BD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

To achieve optimum patient outcomes, clinicians must strive to practice evidence-based medicine wherever possible. Evidence-based practice has two requirements: the availability of published research[1], and the ability to critically appraise the information presented[2].

Decisions regarding treatment should thus be informed by the experience of others, as presented in peer-reviewed medical and scientific journals. Clinicians must however be aware of bias and inaccuracy, and be prepared to question such literature. Publication does not guarantee quality, and there is a hierarchy of evidence ranging from that derived through expert opinion and case report, to that supported by large-scale randomized controlled trials[3].

This is particularly important for the management of rare diseases, where there may not be a widely-accepted “gold-standard” treatment, and also in complex multi-system diseases, where there are likely to be a range of potential treatment options depending on the presenting features. Behçet’s Disease (BD) is both rare and complex: is a multi-system inflammatory disorder of unknown aetiology[4], with an estimated incidence of 0.64 per 100,000 people in the UK and 5.2 per 100,000 in the USA. Higher disease rates are observed in Mediterranean and Far Eastern countries along the historic “Silk Route”, with disease incidence in Turkey between 20 and 421 per 100,000 people[5].

Patients display a diverse spectrum of symptoms, both in terms of organ system affected and also the severity of disease in each of these systems[6]. As a result, disease management is variable with therapeutic options ranging from symptomatic relief through to systemic immunosuppression[7, 8]. Treatment is usually instigated and monitored by a multi-disciplinary team, involving collaboration between dermatologists, ophthalmologists and rheumatologists, with input by cardiologists, genitourinary physicians and neurologists as required.

It follows that best practice in BD demands a large body of supporting literature; it is important that each member of the multi-disciplinary team has access to up-to-date evidence to guide their management, with supporting data for each potential disease manifestation, at varying degrees of severity.

We set out to investigate the scope and quality of the evidence-base available to clinicians involved in the management of BD, paying particular attention to how this literature has evolved over time. We were keen to determine if it is possible to practice evidence-based medicine for all potential disease manifestations and through review of observed trends to identify any areas of unmet need, to guide further research in this area. This was achieved through a comprehensive review of all available peer-reviewed literature, assessing the range of therapeutic options investigated, the disease manifestations for which these investigations were performed and the overall quality of the resulting research.

Methods

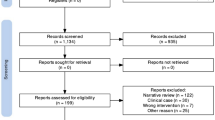

A systematic online literature search was performed using the PubMed database, Medline, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) for all studies published before August 2013 combining the terms “therapy OR therapeutic OR treatment”, “behçet*” (exploded), and all publication types relating to clinical trials as listed in the PubMed database.

To be considered for further review, studies were assessed against strict inclusion and exclusion criteria; for inclusion, all documented cases of BD must have been diagnosed according to the International Study Group (ISG) guidelines (1990)[9], or for those studies recruiting patients prior to the publication of these guidelines, diagnosis of BD must have been deemed concordant with ISG criteria by all authors of this review. Furthermore, the study must have been directly concerned with a therapeutic intervention. Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions were included in the review.

Publications were excluded if the intervention group comprised fewer than 20 patients with ISG-confirmed BD, or if the study did not directly assess a therapeutic option. Duplicates, narrative reviews and editorials were excluded from further analysis. Due to the native language of the reviewers, we were unable to assess studies without an English language translation. Since our aim was to assess the range of data currently available, previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews were also excluded from the quantitative analysis.

Data extracted comprised date of publication, number of patients with ISG-confirmed BD, disease manifestations investigated and whether this was as a primary or secondary study outcome, and therapeutic intervention(s) assessed. Quality was assessed in accordance with the Scottish Intercollegiate Grading Network (SIGN) hierarchy of evidence grading for published literature[3], using a simplified categorization as indicated in Table1. Data was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for coding and further analysis.

Results

The initial search identified 255 papers, of which 60 met the above criteria for further review (Table2). Most studies were excluded due to small sample size.

Of the 60 studies included in this analysis, ocular and mucocutaneous manifestations of disease were the most frequently reported primary outcomes (27 and 26 studies respectively), with far fewer studies reporting on cardiovascular, neurological or rheumatological outcomes (Table3). Two studies were primarily concerned with quality of life measures, and two with serological markers of disease with no symptomatic correlation. Eight studies (13.33%) reported on a range of disease manifestations as primary outcomes.

These studies represent an overall sample size of 4302 patients with BD, of which 1555 were involved in studies reporting on ocular outcomes, 1420 mucocutaneous outcomes, 1144 cardiovascular outcomes, 449 rheumatological outcomes, 56 neurological, and 109 other outcomes.

The most commonly reported secondary outcome was rheumatological disease, being assessed in eight studies, with mucocutaneous disease, cardiovascular and neurological disease each being reported as secondary outcome in a further five studies.

A total of 37 distinct therapeutic interventions were assessed, which were categorized as shown in Table4. Most studies investigated pharmacological agents, with only six studies investigating non-pharmacological interventions (ocular surgery, retinal laser, cardiovascular surgery, interventional radiology, dental hygiene and dental surgery).

Between 1988 and 2013, there has been a steady increase in the number of publications reporting on ocular and mucocutaneous disease manifestations as primary outcome measures. During this period, there has been a slower increase in the number of studies reporting on rheumatological disease as primary outcome and little increase in the number of studies reporting on all other manifestations (Figure1).

Since 2007 there has been a significant increase in the number of studies investigating biologic therapies for manifestations of BD (Figure2). The most significant increase has been in those studies reporting on ocular manifestations as primary outcome, for which the cumulative number of studies has increased by 140% since 2009 (Figure3).

According to the SIGN grading for hierarchy of evidence[3], the highest quality research has been conducted for studies reporting on mucocutaneous disease manifestations as primary outcome, followed by those investigating rheumatological outcomes, then ocular outcomes. There are currently no high quality controlled trials of therapy for neurological consequences of BD (Figure4).

There has been a relative decline in the number of SIGN-1 graded studies being published since 2010, compared to a relative increase in lower-quality grade 2 and 3 studies (Figure5).

Discussion

Evidence-based practice demands continuous reappraisal of peer-reviewed literature, and clinicians must be prepared to update treatment guidelines as new therapies are validated. To achieve this, it is useful to assess the scope of published data, both to review those disease manifestations and treatment modalities that have been thoroughly investigated, and identify any which may have been neglected. Through review of current trends in published research we can predict how the situation is likely to evolve over time and identify areas of unmet need for future investigation.

This report represents the first such assessment of trends over time in published literature for the management of BD. We have reviewed the available data with respect to disease manifestations investigated, therapeutic interventions tested and have made an assessment of the quality of this evidence.

We conclude that whilst there is a wealth of published literature available to guide evidence-based practice in BD, there are still worrying gaps in the evidence:

In our analysis, mucocutaneous and ocular manifestations were the most commonly reported primary outcomes, followed by rheumatological disease, with very few studies reporting on neurological or cardiovascular symptoms as primary outcome. These proportions reflect the prevalence of each manifestation in the patient population; in one review mucocutaneous disease was reported in almost all patients, ocular involvement in up to 69%, joint involvement in up to 59%, vascular involvement in up to 38% and central nervous system involvement in up to 20% of patients with BD[6]. It could thus be reasoned that “supply” of literature is largely matched to “demand”.

Review of publication trends over time suggests that whilst the number of studies reporting ocular manifestations as primary outcome are increasing, there have been no new publications using mucocutaneous manifestations as primary outcome since 2009, and none using rheumatological manifestations as primary outcome since 1998. Extrapolating these trends forwards, this suggests a “plateau” in new data generation for certain aspects of disease, with little new data likely to appear in the foreseeable future.

Furthermore, whilst mucocutaneous disease is indeed the most common manifestation of BD, it is the cardiovascular and neurological disease which has the potential to be most serious[5]. Currently, the ability to make evidence-based treatment decisions for neurological and cardiovascular disease manifestations is severely limited by a lack of data, with only four studies employing cardiovascular disease as primary outcome and two neurological disease.

We found no literature to guide interventions in the management of gastro-intestinal disease. This has previously been documented[70] and we find no evidence of changing practice in this area.

The current trend in the types of therapeutic agent assessed reveals a bias towards newer, biologic therapies, with a relative over-representation of studies testing biologics in ocular disease. Again, this reflects the relative frequency and severity of ocular manifestations in BD.

There is a paucity of studies at the highest levels of scientific evidence with over-representation of SIGN-2 and SIGN-3 graded papers. This is particularly noticeable in those studies reporting primary outcomes of ocular disease, which whilst showing the greatest increase in frequency, display one of the lowest incidences of SIGN-1 graded studies. There is currently no SIGN-1 graded literature for management of neurological disease.

Again, it is perhaps most worrying that we observe a relative decrease in the overall frequency of SIGN-1 graded papers over recent years, whilst the frequency of lower quality papers is increasing. Our exclusion criteria eliminated all SIGN-4 graded papers from review.

Given the deficit of published data to guide management of the less common manifestations of BD and the difficulty in performing large-scale randomized controlled trials in rare diseases, clinicians may wish to consider an alternative approach to generation of treatment guidelines. Kobayashi et al. employed a modified Delphi approach in developing guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intestinal BD[71]; this approach involves development of consensus-based guidelines through expert review of a selection of clinical statements extracted from existing literature. It could be argued that rather than being limited to the conventional hierarchy of evidence as described by SIGN, this approach allows a degree of objective assessment of lower-quality studies which would traditionally be excluded from published systematic reviews.

For rare diseases, consensus-based guidelines may necessitate an international collaborative approach, which can be facilitated through centres of excellence[72]. In addition to “physical” centres of excellence in a hospital setting, there is a growing recognition of the value of virtual centres of excellence such as the ORPHANET information portal[73].

We have made no comment on treatment efficacy or side effects in our review. Hatemi et al. have previously published detailed guidelines for the management of BD, both in the form of evidence-based recommendations by The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)[74], and an accompanying systematic review of published literature[70]. An independent management algorithm was proposed in a wider review article by Alpsoy in 2012[75], and a Cochrane review of pharmacotherapy in BD was published in 2009[76]. These publications currently constitute the “gold standard” for clinicians wishing to review treatment outcomes in existing literature, and provide a strong foundation on which to base treatment decisions.

Clinicians should however be aware of the limitations of these existing reviews: The EULAR review assessed published literature only up to December 2006 and Alpsoy up to 2010, whilst the Cochrane review (despite being published later) included RCTs up to January 1998. Furthermore, whilst the Alpsoy review is a useful resource, it makes no comment on the quality of referenced studies, and relies on a mixture of primary data and existing review articles. According to our inclusion criteria, we have identified a further 21 studies which were published since the EULAR recommendations were finalized, and a further 16 RCTs since the termination of the Cochrane review in 1998. Our review would suggest an update of each of these existing sources is indicated.

We also note that these existing reviews assess only pharmacological treatment options; high-quality evidence is lacking in other modalities, however we found evidence of ten studies reporting either primary or secondary study outcomes of non-pharmacological therapies. Whilst we acknowledge that surgery and other invasive interventions should be reserved as a last resort, we would urge clinicians to remember the impact of diet and exercise on general health and well being of patients with BD, and consider these areas which would benefit from increased research activity.

This review is subject to a number of limitations: As discussed above, we have made no comment on the detail of study outcomes, and have only categorized them in terms of organ system investigated. We would recommend that clinicians refer to the aforementioned publications by Hatemi et al. for a comprehensive discussion of treatment efficacy[70, 74], but remain aware of the need for frequent updates of published guidelines and be prepared to consult original sources for themselves.

We may also have excluded a number of “useful” publications based on their small sample size; Behçet’s Disease remains relatively rare in many populations[5] and clinicians may struggle to generate large sample sizes for clinical studies. They may however generate interesting data on unusual treatment modalities in small groups, and we would encourage clinicians to assess these studies for themselves.

Conclusions

We conclude that evidence-based practice in BD is currently an ideal and not a feasible reality. To date, there have been numerous studies on treatment for ocular and mucocutaneous manifestations, however the availability of evidence from large scale, randomized controlled trials remains limited and we hope investigation continues in these areas. There is an alarming shortage of research investigating all other disease manifestations, and this is an important area of unmet need that should be addressed through future work.

In addition, whilst current research is biased towards newer biologic therapies, there is significant scope for reappraisal of older agents that may prove to be beneficial in certain situations following rigorous scientific review.

Abbreviations

- BD:

-

Behçet’s disease

- EBM:

-

Evidence based medicine

- EULAR:

-

European league against rheumatism

- ISG:

-

International study group

- SIGN:

-

Scottish intercollegiate guideline network.

References

Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS: Evidence based medicine : what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996, 312: 71-72. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71.

Fowkes FG, Fulton PM: Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ. 1991, 302: 1136-1140. 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1136.

Harbour R, Miller J: A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ. 2001, 323: 334-336.

Direskeneli H: Behçet’s disease: infectious aetiology, new autoantigens, and HLA-B51. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001, 60 (11): 996-1002. 10.1136/ard.60.11.996.

Yazici Y, Yurdakul S, Yazici H: Behçet’s syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010, 12 (6): 429-435. 10.1007/s11926-010-0132-z.

Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G: Behçet’s Disease. NEJM. 1999, 341 (17): 1284-1291. 10.1056/NEJM199910213411707.

Alexoudi I, Kapsimali V, Vaiopoulos A, Kanakis M, Vaiopoulos G: Evaluation of current therapeutic strategies in Behçet’s disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2011, 30 (2): 157-163. 10.1007/s10067-010-1566-4.

Arida A, Fragiadaki K, Giavri E, Sfikakis PP: Anti-TNF agents for Behcet's Disease: analysis of published data on 369 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 41 (1): 61-70. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.09.002.

Wechsler B, Davatchi F, Mizushima Y, Hamza M, Dilsen N, Kansu E, Yazici H, Barnes CG, Chamberlain MA, James DG, Lehner T, O’Duffy JD, Rigby AS, Gregory J, Silman AJ: Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990, 335: 1078-1080.

Sakai T, Watanabe H, Kuroyanagi K, Akiyama G, Okano K, Kohno H, Tsuneoka H: Health- and vision-related quality of life in patients receiving infliximab therapy for Behcet uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013, 97 (3): 338-342. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302515.

Dick AD, Tugal-Tutkun I, Foster S, Zierhut M, Melissa Liew SH, Bezlyak V, Androudi S: Secukinumab in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis: results of three randomized, controlled clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2013, 120 (4): 777-787. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.040.

Yoshida A, Kaburaki T, Okinaga K, Takamoto M, Kawashima H, Fujino Y: Clinical background comparison of patients with and without ocular inflammatory attacks after initiation of infliximab therapy. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012, 56 (6): 536-543. 10.1007/s10384-012-0182-z.

Okada AA, Goto H, Ohno S, Mochizuki M: Ocular Behçet’s Disease Research Group Of Japan. Multicenter study of infliximab for refractory uveoretinitis in Behçet disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012, 130 (5): 592-598. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.2698.

Markomichelakis N, Delicha E, Masselos S, Fragiadaki K, Kaklamanis P, Sfikakis PP: A single infliximab infusion vs corticosteroids for acute panuveitis attacks in Behçet’s disease: a comparative 4-week study. Rheumatology. 2011, 50 (3): 593-597. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq366.

Giardina A, Ferrante A, Ciccia F, Vadalà M, Giardina E, Triolo G: One year study of efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of patients with ocular and neurological Behçet’s disease refractory to standard immunosuppressive drugs. Rheumatol Int. 2011, 31 (1): 33-37. 10.1007/s00296-009-1213-z.

Saadoun D, Wechsler B, Terrada C, Hajage D, Le Thi HD, Resche-Rigon M, Cassoux N, Le Hoang P, Amoura Z, Bodaghi B, Cacoub P: Azathioprine in severe uveitis of Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62 (12): 1733-1738. 10.1002/acr.20308.

Inanc MT, Kalay N, Heyit T, Ozdogru I, Kaya MG, Dogan A, Duran M, Kasapkara HA, Gunebakmaz O, Borlu M, Yarlıoglues M, Oguzhan A: Effects of atorvastatin and lisinopril on endothelial dysfunction in patients with Behçet’s disease. Echocardiography. 2010, 27 (8): 997-1003. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01180.x.

Chams-Davatchi C, Barikbin B, Shahram F, Nadji A, Moghaddassi M, Yousefi M, Davatchi F: Pimecrolimus versus placebo in genital aphthous ulcers of Behcet’s disease: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010, 13 (3): 253-258. 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01531.x.

Davatchi F, Shams H, Rezaipoor M, Sadeghi-Abdollahi B, Shahram F, Nadji A, Chams-Davatchi C, Akhlaghi M, Faezi T, Naderi N: Rituximab in intractable ocular lesions of Behcet’s disease; randomized single-blind control study (pilot study). Int J Rheum Dis. 2010, 13 (3): 246-252. 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01546.x.

Yamada Y, Sugita S, Tanaka H, Kamoi K, Kawaguchi T, Mochizuki M: Comparison of infliximab versus ciclosporin during the initial 6-month treatment period in Behçet disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010, 94 (3): 284-288. 10.1136/bjo.2009.158840.

Arabaci T, Kara C, Ciçek Y: Relationship between periodontal parameters and Behçet’s disease and evaluation of different treatments for oral recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Periodontal Res. 2009, 44 (6): 718-725. 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01183.x.

Kiliç H, Zeytin HE, Korkmaz C, Mat C, Gül A, Coşan F, Dinç A, Simşek I, Süt N, Yazici H: Low-dose natural human interferon-alpha lozenges in the treatment of Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology. 2009, 48 (11): 1388-1391. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep237.

Kim WH, Choi D, Kim JS, Ko YG, Jang Y, Shim WH: Effectiveness and safety of endovascular aneurysm treatment in patients with vasculo-Behçet disease. J Endovasc Ther. 2009, 16 (5): 631-636. 10.1583/09-2812.1.

Sun A, Wang YP, Chia JS, Liu BY, Chiang CP: Treatment with levamisole and colchicine can result in a significant reduction of IL-6, IL-8 or TNF-alpha level in patients with mucocutaneous type of Behcet’s disease. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009, 38 (5): 401-405. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00774.x.

Karacayli U, Mumcu G, Simsek I, Pay S, Kose O, Erdem H, Direskeneli H, Gunaydin Y, Dinc A: The close association between dental and periodontal treatments and oral ulcer course in behcet’s disease: a prospective clinical study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009, 38 (5): 410-415. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00765.x.

Köse O, Dinç A, Simşek I: Randomized trial of pimecrolimus cream plus colchicine tablets versus colchicine tablets in the treatment of genital ulcers in Behçet’s disease. Dermatology. 2009, 218 (2): 140-145. 10.1159/000182257.

Davatchi F, Sadeghi Abdollahi B, Tehrani Banihashemi A, Shahram F, Nadji A, Shams H, Chams-Davatchi C: Colchicine versus placebo in Behçet’s disease: randomized, double-blind, controlled crossover trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2009, 19 (5): 542-549.

Tabbara KF, Al-Hemidan AI: Infliximab effects compared to conventional therapy in the management of retinal vasculitis in Behçet disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008, 146 (6): 845-850. 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.09.010.

Kump LI, Moeller KL, Reed GF, Kurup SK, Nussenblatt RB, Levy-Clarke GA: Behçet’s disease: comparing 3 decades of treatment response at the National Eye Institute. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008, 43 (4): 468-472. 10.3129/i08-080.

Protogerou AD, Sfikakis PP, Stamatelopoulos KS, Papamichael C, Aznaouridis K, Karatzis E, Papaioannou TG, Ikonomidis I, Kaklamanis P, Mavrikakis M, Lekakis J: Interrelated modulation of endothelial function in Behcet’s disease by clinical activity and corticosteroid treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007, 9 (5): R90-10.1186/ar2289.

Tasli L, Mat C, De Simone C, Yazici H: Lactobacilli lozenges in the management of oral ulcers of Behçet’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006, 24 (3): S83-S86. Erratum in: Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007, 25(3):507-8

Sharquie KE, Najim RA, Al-Dori WS, Al-Hayani RK: Oral zinc sulfate in the treatment of Behcet’s disease: a double blind cross-over study. J Dermatol. 2006, 33 (8): 541-546. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00128.x.

Mat C, Yurdakul S, Uysal S, Gogus F, Ozyazgan Y, Uysal O, Fresko I, Yazici H: A double-blind trial of depot corticosteroids in Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatology. 2006, 45 (3): 348-352.

Al-Waiz MM, Sharquie KE, A-Qaissi MH, Hayani RK: Colchicine and benzathine penicillin in the treatment of Behçet disease: a case comparative study. Dermatol Online J. 2005, 11 (3): 3.

Ahn JK, Chung H, Yu HG: Vitrectomy for persistent panuveitis in Behçet’s disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005, 13 (6): 447-453. 10.1080/09273940591004232.

Melikoglu M, Fresko I, Mat C, Ozyazgan Y, Gogus F, Yurdakul S, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H: Short-term trial of etanercept in Behçet’s disease: a double blind, placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32 (1): 98-105.

Kötter I, Vonthein R, Zierhut M, Eckstein AK, Ness T, Günaydin I, Grimbacher B, Blaschke S, Peter HH, Stübiger N: Differential efficacy of human recombinant interferon-alpha2a on ocular and extraocular manifestations of Behçet disease: results of an open 4-center trial. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 33 (5): 311-319. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2003.09.005.

Sfikakis PP, Kaklamanis PH, Elezoglou A, Katsilambros N, Theodossiadis PG, Papaefthimiou S, Markomichelakis N: Infliximab for recurrent, sight-threatening ocular inflammation in Adamantiades-Behçet disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004, 140 (5): 404-406.

Nitecki SS, Ofer A, Karram T, Schwartz H, Engel A, Hoffman A: Abdominal aortic aneurysm in Behçet’s disease: new treatment options for an old and challenging problem. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004, 6 (3): 152-155.

Yu P, Bai H, Chen L, Zhang W, Xia Y, Wu G: Clinical study on therapeutic effect of acupuncture on Behcet’s disease. J Tradit Chin Med. 2003, 23 (4): 271-273.

Lashay AR, Rahimi A, Chams H, Davatchi F, Shahram F, Hatmi ZN, Khalkhali H, Beigi B: Evaluation of the effect of acetazolamide on cystoid macular oedema in patients with Behcet’s disease. Eye. 2003, 17 (6): 762-766. 10.1038/sj.eye.6700464.

Krause L, Turnbull JR, Torun N, Pleyer U, Zouboulis CC, Foerster MH: Interferon alfa-2a in the treatment of ocular Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003, 528: 511-519.

Matsuda T, Ohno S, Hirohata S, Miyanaga Y, Ujihara H, Inaba G, Nakamura S, Tanaka S, Kogure M, Mizushima Y: Efficacy of rebamipide as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers in patients with Behçet’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Drugs R D. 2003, 4 (1): 19-28. 10.2165/00126839-200304010-00002.

Sharquie KE, Najim RA, Abu-Raghif AR: Dapsone in Behçet’s disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. J Dermatol. 2002, 29 (5): 267-279.

Mudun BA, Ergen A, Ipcioglu SU, Burumcek EY, Durlu Y, Arslan MO: Short-term chlorambucil for refractory uveitis in Behcet’s disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2001, 9 (4): 219-229. 10.1076/ocii.9.4.219.3957.

Yurdakul S, Mat C, Tüzün Y, Ozyazgan Y, Hamuryudan V, Uysal O, Senocak M, Yazici H: A double-blind trial of colchicine in Behçet’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44 (11): 2686-2692. 10.1002/1529-0131(200111)44:11<2686::AID-ART448>3.0.CO;2-H.

Adler YD, Mansmann U, Zouboulis CC: Mycophenolate mofetil is ineffective in the treatment of mucocutaneous Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Dermatology. 2001, 203 (4): 322-324. 10.1159/000051781.

Fujino Y, Joko S, Masuda K, Yagi I, Kogure M, Sakai J, Usui M, Kotake S, Matsuda H, Ikeda E, Mochizuki M, Nakamura S, Ohno S: Ciclosporin microemulsion preconcentrate treatment of patients with Behçet’s disease. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1999, 43 (4): 318-326. 10.1016/S0021-5155(99)00025-8.

Alpsoy E, Er H, Durusoy C, Yilmaz E: The use of sucralfate suspension in the treatment of oral and genital ulceration of Behçet disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Dermatol. 1999, 135 (5): 529-532.

Kosar A, Haznedaroglu S, Karaaslan Y, Büyükasik Y, Haznedaroglu IC, Ozath D, Sayinalp N, Ozcebe O, Kirazli S, Dündar S: Effects of interferon-alpha2a treatment on serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha2 receptor, interleukin-2, interleukin-2 receptor, and E-selectin in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int. 1999, 19 (1-2): 11-14. 10.1007/s002960050091.

Zouboulis CC, Orfanos CE: Treatment of Adamantiades-Behçet disease with systemic interferon alfa. Arch Dermatol. 1998, 134 (8): 1010-1016.

Hamuryudan V, Mat C, Saip S, Ozyazgan Y, Siva A, Yurdakul S, Zwingenberger K, Yazici H: Thalidomide in the treatment of the mucocutaneous lesions of the Behçet syndrome. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 128 (6): 443-450. 10.7326/0003-4819-128-6-199803150-00004.

Calgüneri M, Ertenli I, Kiraz S, Erman M, Celik I: Effect of prophylactic benzathine penicillin on mucocutaneous symptoms of Behçet’s disease. Dermatology. 1996, 192 (2): 125-128. 10.1159/000246336.

Sakane T, Mochizuki M, Inaba G, Masuda K: A phase II study of FK506 (tacrolimus) on refractory uveitis associated with Behçet’s disease and allied conditions. Ryumachi. 1995, 35 (5): 802-813.

Moral F, Hamuryudan V, Yurdakul S, Yazici H: Inefficacy of azapropazone in the acute arthritis of Behçet’s syndrome: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995, 13 (4): 493-495.

Gardner-Medwin JM, Smith NJ, Powell RJ: Clinical experience with thalidomide in the management of severe oral and genital ulceration in conditions such as Behçet’s disease: use of neurophysiological studies to detect thalidomide neuropathy. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994, 53 (12): 828-832. 10.1136/ard.53.12.828.

Hamuryudan V, Moral F, Yurdakul S, Mat C, Tüzün Y, Ozyazgan Y, Direskeneli H, Akoglu T, Yazici H: Systemic interferon alpha 2b treatment in Behçet’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1994, 21 (6): 1098-1100.

Hayasaka S, Kawamoto K, Noda S, Kodama T: Visual prognosis in patients with Behçet’s disease receiving colchicine, systemic corticosteroid or cyclosporin. Ophthalmologica. 1994, 208 (4): 210-213. 10.1159/000310490.

Ozyazgan Y, Yurdakul S, Yazici H, Tüzün B, Işçimen A, Tüzün Y, Aktunç T, Pazarli H, Hamuryudan V, Müftüoğlu A: Low dose cyclosporin A versus pulsed cyclophosphamide in Behçet’s syndrome: a single masked trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992, 76 (4): 241-243. 10.1136/bjo.76.4.241.

Hamuryudan V, Yurdakul S, Rosenkaimer F, Yazici H: Inefficacy of topical alpha interferon in the treatment of oral ulcers of Behçet’s syndrome: a randomized, double blind trial. Br J Rheumatol. 1991, 30 (5): 395-396.

Benamour S, Bennis R, Messoudi M, Zaoui A, Amor B: Desensitization by autologous saliva and Behçet’s disease. Rev Med Interne. 1991, 12 (5): 339-342. 10.1016/S0248-8663(05)80843-4.

Elidan J, Levi H, Cohen E, BenEzra D: Effect of cyclosporine A on the hearing loss in Behçet’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991, 100 (6): 464-468.

Kazokoglu H, Saatçi O, Cuhadaroglu H, Eldem B: Long-term effects of cyclophosphamide and colchicine treatment in Behçet’s disease. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991, 23 (4): 148-151.

Simsek H, Dundar S, Telatar H: Treatment of Behçet disease with indomethacin. Int J Dermatol. 1991, 30 (1): 54-57. 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb05883.x.

Yazici H, Pazarli H, Barnes CG, Tüzün Y, Ozyazgan Y, Silman A, Serdaroğlu S, Oğuz V, Yurdakul S, Lovatt GE, Yazici B, Somani S, Müftüoğlu A: A controlled trial of azathioprine in Behçet’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990, 322 (5): 281-285. 10.1056/NEJM199002013220501.

Hamuryudan V, Yurdakul S, Serdaroglu S, Tüzün Y, Rosenkaimer F, Yazici H: Topical alpha interferon in the treatment of oral ulcers in Behçet’s syndrome: a preliminary report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1990, 8 (1): 51-54.

Masuda K, Nakajima A, Urayama A, Nakae K, Kogure M, Inaba G: Double-masked trial of cyclosporin versus colchicine and long-term open study of cyclosporin in Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1989, 1 (8647): 1093-1096.

Davies UM, Palmer RG, Denman AM: Treatment with acyclovir does not affect orogenital ulcers in Behçet’s syndrome: a randomized double-blind trial. Br J Rheumatol. 1988, 27 (4): 300-302. 10.1093/rheumatology/27.4.300.

BenEzra D, Cohen E, Chajek T, Friedman G, Pizanti S, de Courten C, Harris W: Evaluation of conventional therapy versus cyclosporine A in Behçet’s syndrome. Transplant Proc. 1988, 20 (3 Suppl 4): 136-143.

Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, Houman MH, Kotter I, Olivieri I, Salvarani C, Sfikakis PP, Siva A, Stanford MR, Stubiger N, Yurdakul S, Yazici H: Management of Behçet disease: a systematic literature review for the European League Against Rheumatism evidence-based recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68 (10): 1528-1534. 10.1136/ard.2008.087957.

Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, Iwao Y, Fukushima T, Hiwatashi N, Masahiro I, Bun-Ei I, Takahide M, Toshiyuki M, Takayuki M, Akira S, Mitsuhiro T, Toshifumi H: Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol. 2007, 42: 737-745. 10.1007/s00535-007-2090-4.

Taylor CM, Karet Frankl FE: Developing a strategy for the management of rare diseases. BMJ. 2012, 344: e2417-10.1136/bmj.e2417.

Rath A, Olry A, Dhombres F, Brandt MM, Urbero B, Ayme S: Representation of rare diseases in health information systems: the orphanet approach to serve a wide range of end users. Hum Mutat. 2012, 33 (5): 803-808. 10.1002/humu.22078.

Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, Houman MH, Kotter I, Olivieri I, Salvarani C, Sfikakis PP, Siva A, Stanford MR, Stubiger N, Yurdakul S, Yazici H: EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67 (12): 1656-1662. 10.1136/ard.2007.080432.

Alpsoy E: New evidence-based treatment approach in Behçet’s disease. Patholog. Res. Int. 2012, 2012: 871019.

Saenz A, Ausejo M, Shea B, Ga W, Welch V, Tugwell P: Pharmacotherapy for Behçet’s syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998(Suppl 4):. Art No.: CD001084. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001084.

Acknowledgements

RB is funded by a Fight for Sight (UK) clinical fellowship. AD is funded by Fight for Sight (UK) and Olivia’s Vision (UK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BM, RM, HK, NJ and MM performed the initial scoping study to identify papers for inclusion in this analysis and generated preliminary results on which this manuscript is based. RB reviewed this initial scoping study, finalized the list of papers for inclusion, completed the final analyses and produced the manuscript. AD and PM conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Barry, R.J., Markandey, B., Malhotra, R. et al. Evidence-based practice in Behçet’s disease: identifying areas of unmet need for 2014. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9, 16 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-16

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-16