Abstract

Background and aims

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is a relatively new treatment for liver tumor. The outcomes of SBRT for liver tumor unfit for ablation and surgical resection were evaluated.

Methods

Liver tumor patients treated with SBRT in seven Japanese institutions were studied retrospectively. Patients given SBRT for liver tumor between 2004 and 2012 were collected. Patients treated with SBRT preceded by trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) were eligible. Seventy-nine patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and 51 patients with metastatic liver tumor were collected. The median biologically effective dose (BED) (α/β = 10 Gy) was 96.3 Gy for patients with HCC and 105.6 Gy with metastatic liver tumor.

Results

The median follow-up time was 475.5 days in patients with HCC and 212.5 days with metastatic liver tumor. The 2-year local control rate (LCR) for HCC and metastatic liver tumor was 74.8% ± 6.3% and 64.2 ± 9.5% (p = 0.44). The LCR was not different between BED10 ≥ 100 Gy and < 100 Gy (p = 0.61). The LCR was significantly different between maximum tumor diameter > 30 mm vs. ≤ 30 mm (64% vs. 85%, p = 0.040) in all 130 patients. No grade 3 laboratory toxicities in the acute, sub-acute and chronic phases were observed.

Conclusions

There was no difference in local control after SBRT in the range of median BED10 around 100 Gy for between HCC and metastatic liver tumor. SBRT is safe and might be an alternative method to resection and ablation.

Summary

There was no difference in local control after SBRT in the range of median BED10 around 100 Gy for between HCC and metastatic liver tumor and SBRT is safe and might be an alternative method to resection and ablation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Japan, an infection rate of the hepatitis C is high, and there are many hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases. The liver is also a common lesion of metastases from most common solid malignancies. According to clinical practice guidelines from Japan, resection, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and liver transplantation are the available curative options for HCC [1]. Recently, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) has become a treatment option for patients with liver tumor who are not eligible for surgery, RFA, or liver transplantation. Although HCC doesn’t really have bad radiation sensitivity [2], what’s happening now is that SBRT for HCC has not been performed very much. One of the reasons is that the role of radiotherapy (RT) for liver tumors has been limited due to the risk of radiation-induced liver disease (RILD) [3]. However, technological advances have made it possible for radiation to be delivered to small liver tumors while reducing the risk of RILD [4]. Resection, RFA, or trance-catheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) are often performed for HCC and liver metastasis in Japan. However, only 10–20% of HCC patients have a resectable disease [5]. A drawback to RFA is that some anatomic areas make the procedure difficult to perform [6]. It is only the case with a central lesion of the liver, with direct invasion into the vessels, and/or that an effect of TACE was insufficient to be introduced to SBRT. In patients with centrally located HCC with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis, major resection is often contraindicated due to insufficient residual liver volume [7]. RFA is therefore often contraindicated for HCC in those areas, which are located in and near the hepatic portal vein or central bile duct [8] and abutting the diaphragm [6]. Additionally, the risk of neoplastic seeding along the needle track after RFA has been reported [9].

SBRT offers an alternative, non-invasive approach to the treatment of liver metastasis. The goal of SBRT is to deliver a high dose to the target, thereby providing better local tumor control, while limiting dose to surrounding healthy tissue, thereby potentially decreasing complication rates. Early applications of SBRT to liver metastases have been promising [10–20]. While these data establish the safety of stereotactic radiation therapy for liver metastases, all SBRT treatments must be performed cautiously given the challenges of organ motion and the low radiation tolerance of the surrounding hepatic parenchyma.

Takeda et al.[21] reported that local control rate (LCR) after SBRT for lung metastases from colorectal cancer with a 2-year LCR of 72% was worse than that for primary lung cancer. We hypothesized that the same thing as this might apply to HCC and liver metastasis and, in other words, LCR after SBRT for liver metastases might be worse than that for HCC.

Because there was little number of cases that has performed liver SBRT in every each institution, we wanted to research results and a side effect as a whole in many institutions. The purpose of this study was to retrospectively evaluate the outcomes, mainly concerning local control, of patients treated at various dose levels in many Japanese institutions.

Materials and methods

Patients

This is a retrospective study to review 130 patients with primary or metastatic liver cancers treated at seven institutions extracted from the database of Japanese Radiological Society multi-institutional SBRT study group (JRS-SBRTSG). The investigation period was from May 2004 to November 2012.

The diagnosis of HCC depended mostly on imaging studies, because candidates for SBRT were unfeasible for pathological confirmation. During follow-up of patients with liver disease, nodules ≥1 cm were diagnosed as HCC based on the typical hallmarks (hyper-vascular in the arterial phase with washout in the portal, venous or delayed phases) from imaging studies, which included a combination of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, 4-phase multi-detector computed tomography (CT), dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and CT during hepatic arteriography and arterio-portography studies. The diagnosis was established according to a review [22] and clinical practice guidelines [23, 24]. The eligibility of SBRT for HCC was a single lesion in principle.

The diagnosis of metastatic liver tumor was confirmed by diagnostic imaging including ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI. The eligibility of SBRT for metastatic liver tumor was without other lesions and in less than four.

Patient and tumor characteristics were shown in Table 1. HCC included 79 cases and the liver metastases included 51 cases. The Child-Pugh score before SBRT for HCC was 84.8% in grade A, 11.4% in grade B, and 1.3% in grade C. Ischemic HCC was 16/79 cases (20%) and plethoric HCC was 55/79 cases (70%). The median alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (ng/mL) and des-gamma carboxy prothrombin (PIVKA-II) (AU/mL) value before SBRT for evaluable 73 patients with HCC were 12.7 (range; 0.8-8004) and 35 (range; 3.1-16900). The median indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min (ICG15) value before SBRT for evaluable 25 patients with HCC was 21.2% (range; 3–56.2%). This SBRT was the first treatment in 26/79 cases (33%) and was the first treatment about the same lesion as this SBRT in the additional 7 cases. About the primary tumor site of liver metastases, colo-rectum was 58.8%, lung was 9.8%, and stomach was 9.8%. The number of SBRT lesions was from 1 to 4 (solitary was 41/51 cases) for liver metastasis.

Treatment

For treatment planning, abdominal pressure corsets such as body shell or vacuum cushion such as blue back were used, and it was confirmed that tumor motion was <1 cm. Then, the gross tumor volume (GTV) was delineated on the both inspiratory and expiratory planning CT images in the case of respiratory depression method. The breath-holding method was used in 36 cases, gating method in 10 cases, and respiratory depression method in 25 cases about HCC patients. The planning target volume (PTV) was configured considering respiratory movement, a set-up margin, and a sub-clinical margin (Figure 1). SBRT was performed with an X-ray beam linear accelerator of 6 MV. The total dose was delivered depending on judgment each institution. A collapsed cone (CC) convolution, superposition algorithm, or analytical anisotropic algorithm (AAA) was used for dose calculations.

The mode value of total irradiated dose was 48 Gy in 4 fractions (38/79 cases) (from 40 Gy in 4 fractions to 60 Gy in 10 fractions) for HCC and 48 Gy in 4 fractions (12/51 cases) and 52 Gy in 4 fractions (16/51 cases) (from 30 Gy in 3 fractions to 60 Gy in 8 fractions) for metastatic liver tumor. The biologically effective dose (BED) (α/β = 10 Gy) was 75–106 Gy (median: 96 Gy) for patients with HCC and 56–134 Gy (median: 106 Gy) with metastatic liver tumor (Table 1). The formula about BED10 was used; BED (Gy10) = nd (1 + d/α/β). In all 130 cases, CT registration like cone beam CT was performed each treatment.

SBRT was delivered using multiple non-coplanar static beams (using > 7 non-coplanar fields) generated by a linear accelerator or volumetric modulated arc therapy. Daily image guidance, by using either orthogonal X-rays or onboard CT imaging, was used to re-localize the target before treatment delivery.

Trans-catheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in 7 HCC patients, FOLFILI regimen (folinic acid, fluorouracil, plus irinotecan) in a metastatic liver tumor patient, or TAXOL® (paclitaxel) in a metastatic liver tumor patient was performed before SBRT. Oral TS-1 was combined concurrently with SBRT in an HCC patient.

Follow up

Patients were seen monthly for 1 year after SBRT and tri-monthly thereafter. Laboratory tests were done at every visit. Treatment responses and intrahepatic recurrences were evaluated with dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MRI every 3 months with modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) [25]. Toxicity was evaluated with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0. Acute and sub-acute toxicities were defined as adverse events occurring within 3 months and 3–6 months, respectively, after SBRT. Late toxicities related with liver and other toxicities were defined as those occurring after 6–12 months and from 6 months to last follow-up, respectively. Laboratory tests included aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, platelet count, and albumin.

Local recurrence was defined as progressive disease in mRECIST or the new appearance of a lesion within the PTV, and local control was defined as free of local recurrence. Local control was defined as freedom from local progression by mRECIST.

Statistical analysis

Control and survival rates were calculated with Kaplan-Meier analysis. Log-rank testing was used to compare outcomes between the subsets of patients analyzed. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used for multivariate analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The points on survival curves by Kaplan Meier are a censored case.

Results

Eligible patients

The median follow-up time was 475.5 days (range; 101–2050 days) in patients with HCC and 212.5 days (range; 26–2713 days) with metastatic liver tumor. SBRT was performed as scheduled and was feasible in all patients. At the last follow-up, 48/79 cases (61%) were survival and 31/79 (39%) were dead for HCC and 42/51 cases (82%) were survival and 9/51 cases (18%) were dead for metastatic liver tumors.

Treatment outcomes

Clinical results were shown in Table 2. As to the initial local effect, complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) were 45.6% and 35.4% in SBRT for HCC and 29.4% and 45.1% for metastatic liver tumor, respectively.

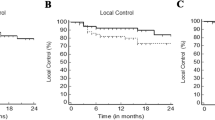

The 2-year cumulative LCR for HCC and metastatic liver tumor was 74.8% ± 6.3% (standard error) and 64.2 ± 9.5% (p = 0.44) (Figure 2). The LCR was not different between BED10 ≥ 100 Gy (69.0% ± 7.6% at 2 years) vs. < 100 Gy (72.4% ± 7.7%) in all 130 patients (p = 0.61) (Figure 3). The LCR was not different between HCC (68.2% ± 11.2%) vs. liver metastasis (68.3% ± 11.2%) in 70 patients with the higher BED10 ≥ 100 Gy (p = 0.96). The LCR was not different between BED10 ≥ 100 Gy (68.3% ± 11.2%) vs. < 100 Gy (46.5% ± 16.9%) in 51 patients with liver metastasis (68.2% ± 11.2% vs. 79.2% ± 7.7%, p = 0.72) and in 79 patients with HCC (p = 0.43). In all 130 patients, the LCR was not different between maximum tumor diameter > 20 mm vs. ≤ 20 mm (70.6% ± 7.6% vs. 83.5% ± 7.6%, p = 0.28) and ≥ 40 mm vs. < 40 mm (55.4% ± 17.2% vs. 79.8% ± 5.1%, p = 0.32) except for > 30 mm vs. ≤ 30 mm (64.1% ± 9.1% vs. 85.2% ± 5.6%, p = 0.040) (Figure 4). The LCR was not different between BED10 ≥ 100 Gy (66.2% ± 33.8%) vs. < 100 Gy (62.3% ± 12.6%) in 41 patients with the bigger tumor diameter > 30 mm (p = 0.78). The LCR was not different between older (>70 y.o.) vs. younger (≤70 y.o.) (74.4% ± 6.2% vs. 70.6% ± 8.9%, p = 0.76).

By multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazards regression analysis), the maximum tumor diameter > 30 mm vs. ≤ 30 mm (other covariates were BED10 ≥ 100 Gy vs. <100 Gy of p = 0.70, age >70 y.o. vs. ≤ 70 y.o. of p = 0.73, HCC vs. metastatic liver tumor of p = 0.52) was the only significant factor for LCR (p = 0.047, 95% CI = 1.014-7.546).

The scatter diagram between BED10 and local control time was shown in Figure 5. There was no correlation between BED10 and local control time. We didn’t show the fact that the higher BED10 was, the longer local control time was.

The 2-year overall survival (OS), cause specific survival (CSS), disease free survival (DFS), and distant metastatic free survival (DMF) were 52.9% ± 7.1%, 69.0% ± 6.9%, 39.9% ± 6.9%, and 76.3% ± 6.6% in 79 patients with HCC, respectively (Figure 6). The number of patients at risk was 43, 21, 9, and 3 at 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-year in OS, respectively. The 2-year OS was 71.9% ± 9.4% in 51 patients with metastatic liver tumor.

The 2-year cumulative LCR for HCC (n = 79) vs. metastatic liver tumor from colorectal cancer (n = 30) vs. from other cancers (n = 21) was 74.1% ± 6.2% vs. 54.2% ± 11.8% vs. 87.5% ± 11.7% (p = 0.18 by comparison among three groups, p = 0.12 between colorectal and other cancers, and p = 0.16 between HCC and colorectal cancer).

Treatment-related toxicity

All SBRT were completed without toxicity during RT period. There was no Grade 5 toxicity. Nine patients (7%) experienced Grade 2–4 gastrointestinal toxicity. Three patients had Grade 2 gastric inflammations at both 1 Mo (40 Gy in 4 fractions and 60 Gy in 10 fractions) and one gastric ulcer at 27 Mo (60 Gy in 10 fractions). Four had Grade 3 intestinal tract bleedings at 5 Mo (50 Gy in 5 fractions) and 6 Mo (40 Gy in 4 fractions) and transverse colon ulceration at 5 Mo (60 Gy in 10 fractions) and duodenal ulcer at 17 Mo (48 Gy in 4 fractions) without chemotherapy in all 4 cases. One patient had Grade 4 gastro-duodenal artery rupture at 6 Mo after SBRT of 48 Gy in 4 fractions without chemotherapy. One patient complained of chest wall pain after SBRT of 45.2 Gy in 4 fractions combined with TACE.

No significant (≥ grade 3) liver enzyme elevation was observed during treatment. No classic RILD was observed.

Discussion

This is a retrospective study to review 130 patients with primary or metastatic liver cancers treated at 20 institutions extracted from the database of JRS-SBRTSG. The primary aim of the paper is to report outcome in terms of survival, local control, and toxicity. Overall survivals in this study of 53% for HCC (n = 79) and 72% for liver metastases (n = 51) at 2 year after SBRT were almost satisfactory (median follow-up was 16 months), but there were various biases in that the candidates included frail patients contraindicated due to decompensated cirrhosis and older patients with a median age of 73 years. It was the reason why only LCR was performed for the factor analysis in this study.

The local controls after stereotactic body radiotherapy for liver tumor were 65% to 100% in HCC and 56% to 100% in metastatic liver tumor. Results of phase I/II studies and retrospective series of SBRT for HCC patients indicated high local control rates of 90-100% [26–29]. In this study, local recurrence was seen at within 8 months in almost all cases and at 20 to 23 months in some cases. The LCR of HCC in this study was slightly poor and could hardly have been more different from that of metastatic liver tumor. We showed the summary of LC after SBRT for liver tumor in Table 3.

LCR might be overestimated using cumulative LCR like the present report because patients who died without the evidence of local recurrence were excluded. Since the pure LCR want to be calculated, the patients who died without local recurrence were treated as a censored case. Takeda et al.[21] reported that LCR after SBRT for lung metastases from colorectal cancer with a 2-year LCR of 72% was worse than that for primary lung cancer and also in the present study, LCR for liver metastases from colorectal cancer was slightly worse than that for HCC or liver metastases from other cancers, although there was no significant difference. The patient number at this time may be too small to detect the significant differences on LCR among three groups.

To improve our results of local control and so on, we may increase radiation dose. The median BED10 in this study was 96 Gy for patients with HCC and 106 Gy with metastatic liver tumor. Although it is natural that BED10 is over 100 Gy in the SBRT for lung tumor, the fact may be not true of the SBRT for liver tumor. Although the aim of SBRT is to deliver a high ablative dose to destroy tumor cells, the optimal treatment dose should be determined based on both tumor control and long-term safety because radiation damage to the normal liver tissue is dose-volume-dependent [35, 36]. In SBRT for liver tumors, the prescribed dose and fraction vary across studies, ranging from 24–60 Gy in 2–6 fractions, and most studies focused predominantly on liver metastases [37]. Since metastatic lung tumors require dose escalation due to relatively low radio-sensitivity [38], increasing the dose to metastatic liver tumors appears to be reasonable, and patients with normal liver function treated with SBRT have rarely developed RILD. In contrast, dose escalation in HCC patients with decompensated cirrhotic liver disease may be disadvantageous with respect to normal liver tolerance. A dose-control relationship has been described for patients treated with SBRT for liver and lung metastases. In an analysis of 246 lesions treated with three-fraction SBRT for primary or metastatic tumors within the lung or liver, McCammon et al.[39] demonstrated significant improvement in local control with increasing dose and the 3-year local control rate in their series was 89.3% for those lesions that received 54 to 60 Gy versus 59% and 8.1% for lesions that received 36 to 53.9 Gy and less than 36 Gy, respectively (p < 0.01). Tekeda et al.[40] used 35–40 Gy in 5 fractions based on baseline liver function and liver volume receiving ≥20 Gy of SBRT for untreated solitary HCC patients.

By multivariate analysis, the maximum tumor diameter > 30 mm vs. ≤ 30 mm was only one prognostic factor for LCR. According to Rusthoven et al.[17], actuarial in-field local control rates at one & two years after SBRT of 60 Gy in 3 fractions for the treatment of 47 patients with one to three hepatic metastases (63 lesions) were 95% & 92% and 2-year local control was 100% among lesions with maximal diameter of 3 cm or less.

However, this study has some limitations in that it is a retrospective and multi-institutional series with a relatively short follow-up period. The group is very heterogeneous including primary and metastatic liver tumors. That is why the irradiated dose and the follow-up method are inconsistent, too. The reason why there was no difference by the stratification of irradiated dose may be that in this study the problem of algorithm or prescription point can be integrated. We are planning to start a multi-institutional prospective large-scale clinical trial that standardized these factors.

Conclusions

There was no difference in LCR between liver metastasis vs. HCC and the higher vs. lower BED10 against SBRT for liver cancer except for the bigger vs. smaller tumor diameter. SBRT is a safe treatment and may be an alternative option for patients with liver tumor unfit for resection or RFA. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate the effect of SBRT for liver tumor.

References

Arii S, Sata M, Sakamoto M, Shimada M, Kumada T, Shiina S, Yamashita T, Kokudo N, Tanaka M, Takayama T, Kudo M: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: Report of Consensus Meeting in the 45th Annual Meeting of the Japan Society of Hepatology (2009). Hepatol Res 2010, 40: 667-685. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00673.x

Yamashita H, Nakagawa K, Shiraishi K, Tago M, Igaki H, Nakamura N, Sasano N, Siina S, Omata M, Ohtomo K: Radiotherapy for lymph node metastases in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007, 22: 523-527. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04450.x

Garrean S, Hering J, Saied A, Helton WS, Espat NJ: Radiofrequency ablation of primary and metastatic liver tumors: a critical review of the literature. Am J Surg 2008, 195: 508-520. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.06.024

Dawson LA, Normolle D, Balter JM, McGinn CJ, Lawrence TS, Ten Haken RK: Analysis of radiation-induced liver disease using the Lyman NTCP model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002, 53: 810-821. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02846-8

Ikai I, Arii S, Okazaki M, Okita K, Omata M, Kojiro M, Takayasu K, Nakanuma Y, Makuuchi M, Matsuyama Y, Monden M, Kudo M: Report of the 18th follow-up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res 2010, 40: 1043-1059. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00731.x

Rhim H, Lim HK: Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma abutting the diaphragm: the value of artificial ascites. Abdom Imaging 2009, 34: 371-380. 10.1007/s00261-008-9408-4

Torzilli G, Makuuchi M, Inoue K, Takayama T, Sakamoto Y, Sugawara Y, Kubota K, Zucchi A: No-mortality liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients: is there a way? A prospective analysis of our approach. Arch Surg 1999, 134: 984-992. 10.1001/archsurg.134.9.984

Lin SM, Lin CJ, Lin CC, Hsu CW, Chen YC: Randomised controlled trial comparing percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation, percutaneous ethanol injection, and percutaneous acetic acid injection to treat hepatocellular carcinoma of 3 cm or less. Gut 2005, 54: 1151-1156. 10.1136/gut.2004.045203

Yamashita H, Nakagawa K, Shiraishi K, Tago M, Igaki H, Nakamura N, Sasano N, Shiina S, Omata M, Ohtomo K: External beam radiotherapy to treat intra- and extra-hepatic dissemination of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency thermal ablation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006, 21: 1555-1560. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04432.x

Herfarth KK, Debus J, Lohr F, Bahner ML, Rhein B, Fritz P, Höss A, Schlegel W, Wannenmacher MF: Stereotactic single-dose radiation therapy of liver tumors: results of a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol 2001,19(1):164-170.

Wada H, Takai Y, Nemoto K, Yamada S: Univariate analysis of factors correlated with tumor control probability of three-dimensional conformal hypofractionated high-dose radiotherapy for small pulmonary or hepatic tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004,58(4):1114-1120. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.08.012

Kavanagh BD, Schefter TE, Cardenes HR, Stieber VW, Raben D, Timmerman RD, McCarter MD, Burri S, Nedzi LA, Sawyer TE, Gaspar LE: Interim analysis of a prospective phase I/II trial of SBRT for liver metastases. Acta Oncol 2006,45(7):848-855. 10.1080/02841860600904870

Hoyer M, Roed H, Traberg Hansen A, Ohlhuis L, Petersen J, Nellemann H, Kiil Berthelsen A, Grau C, Aage Engelholm S, Von der Maase H: Phase II study on stereotactic body radiotherapy of colorectal metastases. Acta Oncol 2006,45(7):823-830. 10.1080/02841860600904854

Katz AW, Carey-Sampson M, Muhs AG, Milano MT, Schell MC, Okunieff P: Hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for limited hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007,67(3):793-798. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.025

Goodman KA, Wiegner EA, Maturen KE, Zhang Z, Mo Q, Yang G, Gibbs IC, Fisher GA, Koong AC: Dose-escalation study of single-fraction stereotactic body radiotherapy for liver malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010,78(2):486-493. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.020

Lee MT, Kim JJ, Dinniwell R, Brierley J, Lockwood G, Wong R, Cummings B, Ringash J, Tse RV, Knox JJ, Dawson LA: Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy of liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27: 1585-1591. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0600

Rusthoven KE, Kavanagh BD, Cardenes H, Stieber VW, Burri SH, Feigenberg SJ, Chidel MA, Pugh TJ, Franklin W, Kane M, Gaspar LE, Schefter TE: Multi-institutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27: 1572-1578. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6329

Rule W, Timmerman R, Tong L, Abdulrahman R, Meyer J, Boike T, Schwarz RE, Weatherall P, Chinsoo Cho L: Phase I dose-escalation study of stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with hepatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2011, 18: 1081-1087. 10.1245/s10434-010-1405-5

Chang DT, Swaminath A, Kozak M, Weintraub J, Koong AC, Kim J, Dinniwell R, Brierley J, Kavanagh BD, Dawson LA, Schefter TE: Stereotactic body radiotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: a pooled analysis. Cancer 2011, 117: 4060-4069. 10.1002/cncr.25997

Fumagalli I, Bibault JE, Dewas S, Kramar A, Mirabel X, Prevost B, Lacornerie T, Jerraya H, Lartigau E: A single-institution study of stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with unresectable visceral pulmonary or hepatic oligometastases. Radiat Oncol 2012, 7: 164. 10.1186/1748-717X-7-164

Takeda A, Kunieda E, Ohashi T, Aoki Y, Koike N, Takeda T: Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for oligometastatic lung tumors from colorectal cancer and other primary cancers in comparison with primary lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2011,101(2):255-259. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.033

Murakami T, Imai Y, Okada M, Hyodo T, Lee WJ, Kim MJ, Kim T, Choi BI: Ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma: toward improved treatment decisions. Oncology 2011,81(Suppl 1):86-99.

Bruix J, Sherman M: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011, 53: 1020-1022. 10.1002/hep.24199

European association for the study of the liver; European organisation for research and treatment of cancer: EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012, 56: 908-943.

Lencioni R, Llovet JM: Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010, 30: 52-60. 10.1055/s-0030-1247132

Tse RV, Hawkins M, Lockwood G, Kim JJ, Cummings B, Knox J, Sherman M, Dawson LA: Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26: 657-664. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3529

Chi A, Liao Z, Nguyen NP, Xu J, Stea B, Komaki R: Systemic review of the patterns of failure following stereotactic body radiation therapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: clinical implications. Radiother Oncol 2010, 94: 1-11. 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.008

Andolino DL, Johnson CS, Maluccio M, Kwo P, Tector AJ, Zook J, Johnstone PA, Cardenes HR: Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011, 81: e447-e453. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.04.011

Kang JK, Kim MS, Cho CK, Yang KM, Yoo HJ, Kim JH, Bae SH, Jung da H, Kim KB, Lee DH, Han CJ, Kim J, Park SC, Kim YH: Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma as a local salvage treatment after incomplete transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer 2012, 118: 5424-5431. 10.1002/cncr.27533

Blomgren H, Lax I, Näslund I, Svanström R: Stereotactic high dose fraction radiation therapy of extracranial tumors using an accelerator. Clinical experience of the first thirty-one patients. Acta Oncol 1995, 34: 861-870. 10.3109/02841869509127197

Cardenes HR, Price TR, Perkins SM, Maluccio M, Kwo P, Breen TE, Henderson MA, Schefter TE, Tudor K, Deluca J, Johnstone PA: Phase I feasibility trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol 2010, 12: 218-225. 10.1007/s12094-010-0492-x

Kwon JH, Bae SH, Kim JY, Choi BO, Jang HS, Jang JW, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Chung KW: Long-term effect of stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma ineligible for local ablation therapy or surgical resection. Stereotactic radiotherapy for liver cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10: 475. 10.1186/1471-2407-10-475

Louis C, Dewas S, Mirabel X, Lacornerie T, Adenis A, Bonodeau F, Lartigau E: Stereotactic radiotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: preliminary results. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2010, 9: 479-487.

Seo YS, Kim MS, Yoo SY, Cho CK, Choi CW, Kim JH, Han CJ, Park SC, Lee BH, Kim YH, Lee DH: Preliminary result of stereotactic body radiotherapy as a local salvage treatment for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2010, 102: 209-214. 10.1002/jso.21593

Goyal K, Einstein D, Yao M, Kunos C, Barton F, Singh D, Siegel C, Stulberg J, Sanabria J: Cyberknife stereotactic body radiation therapy for nonresectable tumors of the liver: preliminary results. HPB Surg 2010., 2010: doi: 10.1155/2010/309780

Son SH, Choi BO, Ryu MR, Kang YN, Jang JS, Bae SH, Yoon SK, Choi IB, Kang KM, Jang HS: Stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with unresectable primary hepatocellular carcinoma: dose-volumetric parameters predicting the hepatic complication. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010, 78: 1073-1080. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.009

Dawood O, Mahadevan A, Goodman KA: Stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45: 2947-2959. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.011

van Laarhoven HW, Kaanders JH, Lok J, Peeters WJ, Rijken PF, Wiering B, Ruers TJ, Punt CJ, Heerschap A, van der Kogel AJ: Hypoxia in relation to vasculature and proliferation in liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006, 64: 473-482. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.982

McCammon R, Schefter TE, Gaspar LE, Zaemisch R, Gravdahl D, Kavanagh B: Observation of a dose-control relationship for lung and liver tumors after stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 73: 112-118. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.062

Takeda A, Sanuki N, Eriguchi T, Kobayashi T, Iwabutchi S, Matsunaga K, Mizuno T, Yashiro K, Nisimura S, Kunieda E: Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for previously untreated solitary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013, 29: 372-379.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose with respect to this presentation.

Authors’ contributions

HY and HO carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. YM, NM, YM, TN, and TK were gave clinical data in their own institution and corrected the manuscript. KN corrected the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamashita, H., Onishi, H., Matsumoto, Y. et al. Local effect of stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary and metastatic liver tumors in 130 Japanese patients. Radiat Oncol 9, 112 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-9-112

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-9-112