Abstract

Background

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) is the treatment of choice for irresectable meningioma. Due to the strong expression of somatostatin receptors, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) has been used in advanced cases. We assessed the feasibility and tolerability of a combination of both treatment modalities in advanced symptomatic meningioma.

Methods

10 patients with irresectable meningioma were treated with PRRT (177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3 octreotate or - DOTA0,Tyr3 octreotide) followed by external beam radiotherapy (EBRT). EBRT performed after PRRT was continued over 5–6 weeks in IMRT technique (median dose: 53.0 Gy). All patients were assessed morphologically and by positron emission tomography (PET) before therapy and were restaged after 3–6 months. Side effects were evaluated according to CTCAE 4.0.

Results

Median tumor dose achieved by PRRT was 7.2 Gy. During PRRT and EBRT, no side effects > CTCAE grade 2 were noted. All patients reported stabilization or improvement of tumor-associated symptoms, no morphologic tumor progression was observed in MR-imaging (median follow-up: 13.4 months). The median pre-therapeutic SUVmax in the meningiomas was 14.2 (range: 4.3–68.7). All patients with a second PET after combined PRRT + EBRT showed an increase in SUVmax (median: 37%; range: 15%–46%) to a median value of 23.7 (range: 8.0–119.0; 7 patients) while PET-estimated volume generally decreased to 81 ± 21% of the initial volume.

Conclusions

The combination of PRRT and EBRT is feasible and well tolerated. This approach represents an attractive strategy for the treatment of recurring or progressive symptomatic meningioma, which should be further evaluated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While surgery is the mainstay in treatment of meningioma, external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) offers the only other curative option in meningioma management [1, 2].

For benign (WHO Grade 1) tumors, recommended doses are generally 50–54 Gy in fractions of 1.8–2 Gy, alternatively single doses of 12–16 Gy are used in radiosurgery [1–3]. No clear dose–response relationship has been established justifying higher doses to date.

However, especially higher grade meningiomas (≥WHO II), large, irregular tumors in critical locations and recurrent tumors in both radiation-naive as well as previously irradiated regions would likely benefit from a highly conformal dose escalation without increasing dose to normal tissues [4, 5]

In case of a recurrence after external radiotherapy, results of studies using pharmacological targeted approaches have been modest at best and are often associated with significant toxicities [6].

A potential target for a specific and well tolerable therapy in advanced meningioma is the somatostatin receptor (SSR). About 90% of the meningiomas show SSR expression, especially the receptor subtypes 1 and 2 [7]. Positron emission tomography using 68 Ga-labelled somatostatin analogues (SSR-PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using 111In-octreotid are well established for imaging neuroendocrine tumors and have also shown very promising results for the diagnostic work up and for target volume delineation in radiotherapy treatment planning of meningioma [8–10]. Since many tumors display a fairly strong expression of somatostatin receptors, “peptide receptor radionuclide therapy” (PRRT), which is well evaluated and commonly used in neuroendocrine tumors [11, 12], has already been used in advanced cases of meningioma showing promising results [13–15]. However, in the largest study, published by Bartolomei et al., about one third of the patients showed tumor progression after therapy [15].

In order to increase efficacy of treatment, it seems reasonable to combine external beam radiotherapy and PRRT therapy. Besides delivering a higher radiation dose to the tumor, this approach could also be used to reduce the external beam radiation dose to critical organs at risk next to the tumor such as cranial nerves, brainstem and normal brain. Due to the short range of beta particles, somatostatin analogues labelled with [177Lu], such as 177Lu- DOTATATE (177Lu DOTA0,Tyr3 octreotate) and [177Lu]-DOTATOC (177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3octreotide) are of special interest.

We herein report the tolerance and feasibility of a combined PRRT-EBRT approach with one cycle of radiopeptide therapy preceeding EBRT in patients with symptomatic non-resectable meningioma.

Materials and methods

Patients

From May 2010 to May 2011, 10 patients with irresectable advanced primary or recurrent meningioma (7 WHO grade I, 2 grade II, 1 not known) were treated with radiopeptide therapy and EBRT. As part of treatment planning, all patients received somatostatin receptor PET to assess not only SSR expression but also for a more accurate delineation of the target volume. All cases were initially discussed and assigned to the pilot trial in unanimous decision in an interdisciplinary tumor board including physicians from neurosurgery, radiation oncology, neuroradiology, nuclear medicine and medical oncology. The combined treatment was performed according to German law on a compassionate use basis. All patients gave their informed consent for the procedure. Patient characteristics can be found in Table 1. All except one patient had one or more previous surgeries; one had been previously treated with radiotherapy.

PET imaging and PRRT

All patients were assessed for somatostatin receptor expression by PET prior to initiation of PRRT. Until September 2010 [68 Ga-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotide (Ga-DOTATOC) was employed; due to a change in availability of the precursor peptide, [68 Ga-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate (Ga-DOTATATE) was used thereafter. The somatostatin analogue for PRRT was switched simultaneously for the same reason.

Also, until September 2010, a dedicated PET (Siemens ECAT Exact 47) was used for SSR-PET in the first 6 patients; afterwards a newly installed PET/CT (Siemens Biograph mCT 64) was used.

Data sets of the head were acquired 60 minutes after the injection of 111 ± 35 MBq 68 Ga-DOTATOC/DOTATATE. For the dedicated PET, 3D data were collected for 20 min and corrected for attenuation using Ge-68 line sources, data were reconstructed using filtered back projection.

On the PET/CT, a 10 min 3D data acquisition (matrix: 200 x 200) was started after a low-dose-CT (30 mAs, 120 kV, slice thickness 0.5 mm). After decay and scatter correction, PET data were reconstructed iteratively with attenuation correction using dedicated software (HD.PET, Siemens Esoft).

The maximum standardized uptake value SUVmax as well as the mean SUV in a spherical volume of interest 1 cm in diameter (SUVpeak) in the tumor region with highest tracer uptake were determined (Table 2).

PET data were utilized to estimate the tumor volumes (Table 2). The tumors were delineated with the software ROVER (ABX Germany [16]) by setting thresholds relative to the maximum SUV in the PET data sets, which provided acceptable recovery of the volumes of spheres with comparable sizes in phantom measurements (unpublished Data by MCK and HH).

Prior to PRRT, a preexisting reduced renal function was excluded using 99mTc-MAG3; calculated clearance values were always >50 percent of the normal values, adjusted for age and body surface. Pregnancy was excluded by β-HCG test.

The PRRT followed a standardized protocol with infusion of 1500 mL of lysine-arginine solution (2.5% of lysine and 2.5% of arginine) starting 30 minutes at of 500 mL/hour before therapy for renal protection and standardized antiemetic medication (Ondansetron 4 mg p.o.). Radionuclide therapy was administered over 15–20 minutes using a shielded infusion pump system. Patients remained in the radionuclide therapy ward for 4–5 days.

For dosimetry, whole body scans with a [177Lu] standard were performed daily during hospitalization starting on the day of radionuclide administration (Siemens Ecam Duet, medium energy collimator, 20% window around the 208 keV peak, matrix 256 × 1024, scan speed 20 cm/min) and decay kinetics in the total body and the whole tumor were determined. Additionally, a SPECT/CT of the head was acquired 4–5 days after treatment (Siemens Symbia T2, equipped with a medium energy collimator). SPECT/CT data were reconstructed iteratively (3D-OSEM, 6 subsets, 6 iterations, Gauss filter of 8 mm); both attenuation and scatter were corrected for. The sensitivity of the SPECT/CT scanner in counts/second/kBq was determined from calibration with 177Lu activity standards in a head phantom. For technical reasons, SPECT/CT could not be performed in one patient. Assuming equal decay kinetics in all voxels of the tumor, the tumor decay function was normalized to the absolute activity value measured by SPECT/CT for the voxel with the highest uptake to deduce the maximum voxel dose Dvox.

External beam radiotherapy

EBRT was initiated no later than 9 days (median 2 days) after discharge of the patient from the radionuclide therapy ward.

SSR-PET and contrast enhanced volumetric MR-images were coregistered with the planning CT for all patients and respective GTV (gross tumor volume), CTV (clinical target volume) and PTV (planning target volume) delineated. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy plans were implemented in all cases. 1.8–2.0 Gy were delivered to the D95 surrounding the PTV to a total dose of 40–60 Gy. The total dose depended not only upon treatment volume, location and previous RT, but also on the calculated best estimate of dose from the PRRT at the discretion of the responsible radiation oncologist (RAS, MF). Thus, if vision was to be preserved, the maximum dose for the optic organs at risk was 54 Gy (D01) but, depending on previous RT or calculated PRRT-dose, also substantially lower (i.e.only 45 Gy in patient 2 as shown in Figure 1). All patients were fixated in thermoplastic masks; treatment was image guided with at least weekly conebeam CT [17].

Intensity modulated radiotherapy isodose map of patient no. 2. This patient has a large meningioma with bitemporal spread surrounding the optic nerves and chiasm. Shown are transversal (upper left), sagittal (lower left) and coronal (right) views. In order to err on the side of caution due to the estimated 6.6 Gy PRRT dose, the optic tract was limited to 45 Gy (thick green line) and the PTV encompassing dose was limited to 49 Gy (thick orange line) instead of the originally planned 54 Gy.

Evaluation of toxicity and tumor response

Evaluation preceding therapy included standard documentation of the patient’s history and physical examination. Serum chemistry and a complete blood cell count were obtained. Drug- and radiotherapy-related adverse events and toxicities were evaluated according to the Common Toxicity Criteria of the National Cancer Institute (version 4.0). At four weeks and 3–6 months after therapy, symptoms also were reassessed in the outpatient clinic of the department of radiation oncology; at these occasions serum chemistry and a complete blood cell count were obtained again. For tumor evaluation, contrast enhanced MR imaging was performed for all patients; <25% volume change was considered stable disease, >25% volume increase progressive disease and >25% decrease was deemed partial remission. SSR-PET was performed additionally after 3 – 6 months in 7 patients.

Statistical methods

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 19.0; SPSS Inc.) was used for statistical analyses. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were recorded as mean ± standard deviation (SD), for those without normal distribution, the median and the range are mentioned. For the assessment of the correlation uptakes in PET and doses due to PRRT, a Spearman rank test was used. A P-value of 0.05 or smaller was considered to indicate significance.

Results

PRRT

7.4±0.3 GBq of 177Lu-DOTATOC/-DOTATATE were administered (Table 3). While mean total body residence time was 25.7 ± 7.7 h (range: 14.7–39.3 h), maximum activities in the tumor per 0.11 ³ voxel at 1 hour p.a. back-extrapolated from SPECT/CT ranged from 3 to 557 kBq corresponding to 0.4*10-6 to 70.5*10-6 of the administered activity. The mean lifetime of the activity in the voxels was 63.0 ± 17.7 h (range: 29.7–94.2 h). The resulting tumor dose showed a large variation (median: 7.2 Gy; range 0.2–30.6) (Table 3). A high correlation was observed between the uptakes in PET and PRRT (Spearman’s rank test: P > 0.01). Figure 2 illustrates the posttherapeutic scintigraphic whole body images acquired in one patient. No acute toxicities were observed during PRRT.

EBRT

A median dose of 53.0 Gy (range 41.8–60.0) was administered in 26.7±4.3 fractions using IMRT (Table 3, Figure 1). The radiation dose delivered by PRRT showed large variation; the EBRT target dose was significantly reduced from the planned dose in four of the ten patients because of concerns about anterior optic pathway toxicity due to the summation of doses (Table 3, Figure 1).

The other patients received EBRT as planned, irrespective of the PRRT, since the cumulative dose to neighboring organs at risk was deemed not critical by the responsible radiation oncologists. No unusual toxicities were observed during radiotherapy (Figure 3).

Follow-up

As of November 2011 patients had a follow up of a median 13.4 months (range 4.3 months–17.0 months). All patients were alive.

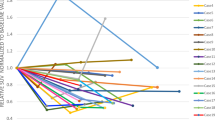

One patient (no. 9) reported a temporary worsening of symptoms about 3–5 months after treatment, which could not be objectified clinically; on MRI, the tumor showed a good partial remission (>50%). Four patients reported an improvement of their symptoms. On morphological imaging, tumor size was stable in 8/10 patients; surprisingly, a complete remission was reported in patient nr.4 on the MRI acquired three months after EBRT. In the 7 patients who had a follow-up SSR-PET, PET based volume estimates decreased to 81% ± 21% (range: 46%–107%; p = 0.029) of the original size. In all of these 7 patients, the SUV values were higher after therapy as compared to the baseline PET. SUVpeak increased by a median of 34% (range: 8%–53%); the corresponding value for SUVmax was 37% (range: 15%–46%).

No chronic effects > Grade 1 have been observed to date after PRRT and EBRT; laboratory values remained unchanged during follow-up.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of combined external beam- PRRT for meningiomas. The combination of these two therapeutic modalities has only been described once in literature; Burdick et al. combined EBRT with 90Y ibritumomab tiuxetan in relapsed or refractory bulky follicular lymphoma [18]. They concluded that EBRT, used to pretreat bulky sites, may improve clinical outcomes and potentially extend survival when combined with radioimmunotherapy. Furthermore, several preclinical mouse and rat model studies of heterotopic and orthotopic glioblastomas have also found a positive synergistic effect of radionuclide therapy and EBRT [19, 20]: by combining both, a stronger reduction in tumor mass was measured than achieved with either treatment modality alone.

Bartolomei et al. reported on single-modality-PRRT using 90Y-DOTATOC as salvage monotherapy in patients with advanced meningioma. Even though therapy was well tolerated, the efficacy was limited, which most likely can be attributed to the limited dose delivered to the tumor [15]. Recently, a successful treatment of metastatic anaplastic meningioma with 177Lu-DOTATATE has also been reported [14].

The small number of patients and short follow up preclude a definitive answer regarding the efficacy of the combination of EBRT and PRRT treatment. The overall positive results (8 patients with morphologically stable disease, one with partial and one with complete response) after a median follow-up of 12.8 months are promising. They compare favorably to the results obtained by using the non-radioactive somatostatin analogue octreotide [21, 22] and the study by Bartolomei et al. [15]. Of course, direct comparison of this study with ours is difficult due to a different patient collective and follow up. However, the short-term results in our study appear to be superior even though the achieved doses are lower than those published for PRRT in neuroendocrine tumors [23].

The current study furthermore has the limitation that we, just like other hospitals, were forced to change from the one somatostatin analogue (DOTATOC) to another one (DOTATATE) due to a change in availability of the GMP-grade precursor. Even though the difference between the two peptides is very small, it results in known alterations of receptor binding and whole body kinetics. Studies comparing the two peptides yield contradictory results on which peptide is superior for clinical use [24, 25]. Nonetheless, as the different peptides do not differ in their dosimetric methodology, this will not affect the validity of the PRRT dosimetry.

In contrast to prior larger studies we opted to use 177Lu as the therapeutic radionuclide even though the alternative, 90Y, has a six-fold higher energy deposition per decay event. This is partly compensated for by the higher activity that can be safely administered and the longer physical half-life of 177Lu. The use of 177Lu has several advantages. Firstly, due to the co-emitted gamma rays, dosimetry is easily feasible with 177Lu but challenging with the pure beta emitter 90Y, especially in smaller structures. Secondly, renal toxicity is lower for 177Lu [26], which is particularly important for patients with a longer life expectancy. Thirdly and most decisive, 177Lu has a much steeper dose gradient curve than 90Y. Figure 4 shows a dose distribution at the surface of a tumor with homogeneous 177Lu or 90Y activity uptake normalized to the maximum absorbed dose inside the tumor. The calculations are based on point dose kernels published in [27]. The relative dose decreases more rapidly with 177Lu than with 90Y. Tissue penetration outside the tumor is negligible for 177Lu; at a distance of 0.3 mm from the tumor surface, the dose delivered by radionuclide therapy is less than 10% of the maximal tumor dose. At least in theory, this should spare critical tissues immediately abutting the tumor (such as cranial nerves and the chiasm). The isotope and activity to be used to treat a specific patient should therefore be selected based on individual parameters such as tumor site, prognosis, radio peptide uptake, renal function, and life expectancy.

In order to avoid severe adverse effects, we chose to err on the side of caution and consequently the target EBRT dose was reduced in four of the patients with tumors very close to critical structures (Figure 1). However, only long term observations and further trials will allow better prediction of whether such a measure is truly necessary as well as which patients will attain a significant dose benefit from such a combined treatment.

Since radiotherapy as a stand-alone therapeutic modality has a high success and disease control rate even in large skull base meningiomas [28, 29], a combined therapy might be most advantageous in advanced cases with tumors in proximity to radiosensitive structures such as the optic nerve, in the re-irradiation setting and for high-grade meningioma.

For a comparison of the absorbed doses of the two treatment modalities (EBBRT and PRRT), several authors suggest the application of the biologically equivalent dose concept [30–32]. In the framework of the present study, the quantities needed for the calculation of the tumor BED were unclear, so the absorbed doses of both treatment modalities were added. Future studies are needed to obtain the parameters for robust BED calculation.

An interesting finding is the increased uptake of Ga-DOTATATE/DOTATOC in meningiomas after the combined therapeutic approach. This was observed in all 7 patients who were reimaged after therapy (Table 2). In order to minimize the effects of the usage of different PET scanners we assessed both the SUVmax and the SUVpeak (the mean SUV in a spherical VOI of 1 cm diameter). The increase was observed for both parameters, so a significant effect of the equipment used appears unlikely. Haug et al. reported in a study on well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors that the tumor-to-spleen SUV ratio was an independent predictor of a longer progression free survival (PFS) after one cycle of PRRT. However, the change of absolute SUVmax did not correlate with PFS [33]. In our study, the tumor-to-spleen-ratio was not calculated because the spleen was not in the field of view. On the other hand, it is known from preclinical studies that neuroendocrine tumors recurring after PRRT have an increased SSR expression [33]. The observation of a SUVmax increase in our patients is not necessarily an indicator of increased receptor expression. Other possible explanations might be an increased blood flow induced by EBRT, the reduction in active tumor (cell) volume after therapy as observed by PET delineation or by reparative/reactive post-radiation changes. When corrected for individual tumor shrinkage, the SUV remains almost unchanged after therapy with a mean deviation of 5% ± 24% (range: -31%–32%). Since no patient progressed during follow-up, no conclusion can be drawn from the present data whether the increase in SUV correlates with prognosis as reported in neuroendocrine tumors in the paper by Haug et al. [33]. However, as a consequence from the observation of generally increasing SUV, PRRT could also be performed after EBRT; either as first cycle or additionally as a second cycle.

Conclusions

Our experiences gained in this pilot phase indicate that peptide receptor radionuclide therapy of meningiomas may be safely used in combination with external beam radiation therapy. This approach represents an attractive strategy for the treatment of irresectable locally recurring, progressive or symptomatic meningioma in order to either increase the dose delivered to the tumor and / or to reduce the dose for organs at risk. Further studies are warranted on the basis of these results.

References

Nicolato A, Foroni R, Alessandrini F, Maluta S, Bricolo A, Gerosa M: The role of Gamma Knife radiosurgery in the management of cavernous sinus meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002, 53: 992-1000. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02802-X.

Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Maitz AH, Lunsford LD: Gamma knife radiosurgery of imaging-diagnosed intracranial meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003, 56: 801-806. 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00126-3.

Spiegelmann R, Cohen ZR, Nissim O, Alezra D, Pfeffer R: Cavernous sinus meningiomas: a large LINAC radiosurgery series. J Neurooncol. 2010, 98: 195-202. 10.1007/s11060-010-0173-1.

Milosevic MF, Frost PJ, Laperriere NJ, Wong CS, Simpson WJ: Radiotherapy for atypical or malignant intracranial meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996, 34: 817-822. 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02166-3.

Hug EB, Devries A, Thornton AF, Munzenride JE, Pardo FS, Hedley-Whyte ET, Bussiere MR, Ojemann R: Management of atypical and malignant meningiomas: role of high-dose, 3D-conformal radiation therapy. J Neurooncol. 2000, 48: 151-160. 10.1023/A:1006434124794.

Chamberlain MC, Barnholtz-Sloan JS: Medical treatment of recurrent meningiomas. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011, 11: 1425-1432. 10.1586/ern.11.38.

Arena S, Barbieri F, Thellung S, Pirani P, Corsaro A, Villa V, Dadati P, Dorcaratto A, Lapertosa G, Ravetti JL, et al: Expression of somatostatin receptor mRNA in human meningiomas and their implication in in vitro antiproliferative activity. J Neurooncol. 2004, 66: 155-166.

Henze M, Schuhmacher J, Hipp P, Kowalski J, Becker DW, Doll J, Macke HR, Hofmann M, Debus J, Haberkorn U: PET imaging of somatostatin receptors using [68GA]DOTA-D-Phe1-Tyr3-octreotide: first results in patients with meningiomas. J Nucl Med. 2001, 42: 1053-1056.

Sweeney RA, Bale RJ, Moncayo R, Seydl K, Trieb T, Eisner W, Burtscher J, Donnemiller E, Stockhammer G, Lukas P: Multimodality cranial image fusion using external markers applied via a vacuum mouthpiece and a case report. Strahlenther Onkol. 2003, 179: 254-260. 10.1007/s00066-003-1031-2.

Gehler B, Paulsen F, Oksuz MO, Hauser TK, Eschmann SM, Bares R, Pfannenberg C, Bamberg M, Bartenstein P, Belka C, Ganswindt U: [68 Ga]-DOTATOC-PET/CT for meningioma IMRT treatment planning. Radiat Oncol. 2009, 4: 56-10.1186/1748-717X-4-56.

Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Kam BL, van Eijck CH, van Essen M, Kooij PP, Feelders RA, van Aken MO, Krenning EP: Treatment with the radiolabeled somatostatin analog [177 Lu-DOTA 0, Tyr3]octreotate: toxicity, efficacy, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 2124-2130. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2553.

Imhof A, Brunner P, Marincek N, Briel M, Schindler C, Rasch H, Macke HR, Rochlitz C, Muller-Brand J, Walter MA: Response, survival, and long-term toxicity after therapy with the radiolabeled somatostatin analogue [90Y-DOTA]-TOC in metastasized neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29: 2416-2423. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7873.

van Essen M, Krenning EP, Kooij PP, Bakker WH, Feelders RA, de Herder WW, Wolbers JG, Kwekkeboom DJ: Effects of therapy with [177Lu-DOTA0, Tyr3]octreotate in patients with paraganglioma, meningioma, small cell lung carcinoma, and melanoma. J Nucl Med. 2006, 47: 1599-1606.

Sabet A, Ahmadzadehfar H, Herrlinger U, Wilinek W, Biersack HJ, Ezziddin S: Successful radiopeptide targeting of metastatic anaplastic meningioma: case report. Radiat Oncol. 2011, 6: 94-10.1186/1748-717X-6-94.

Bartolomei M, Bodei L, De Cicco C, Grana CM, Cremonesi M, Botteri E, Baio SM, Arico D, Sansovini M, Paganelli G: Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with (90)Y-DOTATOC in recurrent meningioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009, 36: 1407-1416. 10.1007/s00259-009-1115-z.

Hofheinz F, Potzsch C, Oehme L, Beuthien-Baumann B, Steinbach J, Kotzerke J, van den Hoff J: Automatic volume delineation in oncological PET. Evaluation of a dedicated software tool and comparison with manual delineation in clinical data sets. Nuklearmedizin. 2012, 51: 9-16.

Boda-Heggemann J, Lohr F, Wenz F, Flentje M, Guckenberger M: kV cone-beam CT-based IGRT: a clinical review. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011, 187 (5): 284-291. 10.1007/s00066-011-2236-4.

Burdick MJ, Neumann D, Pohlman B, Reddy CA, Tendulkar RD, Macklis R: External beam radiotherapy followed by 90Y ibritumomab tiuxetan in relapsed or refractory bulky follicular lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. , 79: 1124-1130.

Israel I, Blass G, Reiners C, Samnick S: Validation of an amino-acid-based radionuclide therapy plus external beam radiotherapy in heterotopic glioblastoma models. Nucl Med Biol. 2011, 38: 451-460. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.12.002.

Samnick S, Romeike BF, Lehmann T, Israel I, Rube C, Mautes A, Reiners C, Kirsch CM: Efficacy of systemic radionuclide therapy with p-131I-iodo-L-phenylalanine combined with external beam photon irradiation in treating malignant gliomas. J Nucl Med. 2009, 50: 2025-2032. 10.2967/jnumed.109.066548.

Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Fadul CE: Recurrent meningioma: salvage therapy with long-acting somatostatin analogue. Neurology. 2007, 69: 969-973. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271382.62776.b7.

Johnson DR, Kimmel DW, Burch PA, Cascino TL, Giannini C, Wu W, Buckner JC: Phase II study of subcutaneous octreotide in adults with recurrent or progressive meningioma and meningeal hemangiopericytoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011, 13: 530-535. 10.1093/neuonc/nor044.

Wehrmann C, Senftleben S, Zachert C, Muller D, Baum RP: Results of individual patient dosimetry in peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu DOTA-TATE and 177Lu DOTA-NOC. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2007, 22 (3): 406-416. 10.1089/cbr.2006.325.

Forrer F, Uusijarvi H, Waldherr C, Cremonesi M, Bernhardt P, Mueller-Brand J, Maecke HR: A comparison of (111)In-DOTATOC and (111)In-DOTATATE: biodistribution and dosimetry in the same patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004, 31: 1257-1262.

Esser JP, Krenning EP, Teunissen JJ, Kooij PP, van Gameren AL, Bakker WH, Kwekkeboom DJ: Comparison of [(177)Lu-DOTA(0), Tyr(3)]octreotate and [(177)Lu-DOTA(0), Tyr(3)]octreotide: which peptide is preferable for PRRT?. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006, 33: 1346-1351. 10.1007/s00259-006-0172-9.

Valkema R, Pauwels SA, Kvols LK, Kwekkeboom DJ, Jamar F, de Jong M, Barone R, Walrand S, Kooij PP, Bakker WH, Lasher J, Krenning EP: Long-term follow-up of renal function after peptide receptor radiation therapy with (90)Y-DOTA(0), Tyr(3)-octreotide and (177)Lu-DOTA(0), Tyr(3)-octreotate. J Nucl Med. 2005, 46 (Suppl 1): 83S-91S.

Botta F, Mairani A, Battistoni G, Cremonesi M, Di Dia A, Fasso A, Ferrari A, Ferrari M, Paganelli G, Pedroli G, Valente M: Calculation of electron and isotopes dose point kernels with FLUKA Monte Carlo code for dosimetry in nuclear medicine therapy. Med Phys. 2011, 38: 3944-3954. 10.1118/1.3586038.

Astner ST, Theodorou M, Dobrei-Ciuchendea M, Auer F, Kopp C, Molls M, Grosu AL: Tumor shrinkage assessed by volumetric MRI in the long-term follow-up after stereotactic radiotherapy of meningiomas. Strahlenther Onkol. 2010, 186 (8): 423-429. 10.1007/s00066-010-2138-x.

Minniti G, Clarke E, Cavallo L, Osti MF, Esposito V, Cantore G, Cappabianca P, Enrici RM: Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy for large benign skull base meningiomas. Radiat Oncol. 2011, 6: 36-10.1186/1748-717X-6-36.

Cremonesi M, Botta F, Di Dia A, Ferrari M, Bodei L, De Cicco C, Rossi A, Bartolomei M, Mei R, Severi S: Dosimetry for treatment with radiolabelled somatostatin analogues. A review. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010, 54: 37-51.

Cremonesi M, Ferrari M, Di Dia A, Botta F, De Cicco C, Bodei L, Paganelli G: Recent issues on dosimetry and radiobiology for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011, 55: 155-167.

Strigari L, Benassi M, Chiesa C, Cremonesi M, Bodei L, D'Andrea M: Dosimetry in nuclear medicine therapy: radiobiology application and results. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011, 55: 205-221.

Haug AR, Auernhammer CJ, Wangler B, Schmidt GP, Uebleis C, Goke B, Cumming P, Bartenstein P, Tiling R, Hacker M: 68 Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT for the early prediction of response to somatostatin receptor-mediated radionuclide therapy in patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med. 2010, 51: 1349-1356. 10.2967/jnumed.110.075002.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Franz R. Kaiser and Stefanie Diessl for their assistance and to the medical team, nurses and technical assistants of the departments of Nuclear Medicine and Radiation Oncology for their support. This publication was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Würzburg in the funding programme “Open Access Publishing”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None of the authors has a conflict of interest; no financial support was received for this project.

Authors’ contribution

MCK: Conceived the combined approach, treated the patients with PRRT, collected and analyzed data, wrote and revised the manuscript. HH: Conceived the combined therapy approach, performed dosimetry in the context of PRRT, wrote parts of and revised manuscript, MLoe: Was involved in the treatment of the patients, revised the manuscript. FAV: Collected and analyzed data, revised the manuscript. MS: Performed the synthesis of 177Lu-DOTATATE/-TOC, revised the manuscript. MLa: Conceived the combined therapy approach, revised the manuscript. CR: Gave valuable input on the study conception, oversaw the treatments, and revised the manuscript. SSS: Conceived the combined therapy approach, revised the manuscript, provided the basis for somatostatin receptor PET and PRRT. AKB: Gave valuable input on the manuscript, oversaw treatments, revised the manuscript. MF: Gave input on the study conception, oversaw the treatments, performed radiotherapy, and revised the manuscript. RAS: Conceived the combined approach, performed radiotherapy, collected and analyzed data wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kreissl, M.C., Hänscheid, H., Löhr, M. et al. Combination of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with fractionated external beam radiotherapy for treatment of advanced symptomatic meningioma. Radiat Oncol 7, 99 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-7-99

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-7-99