Abstract

Background

The Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) is a key P450 enzyme involved in the metabolism of exogenous and endogenous substrates. Previous studies have reported the existence of CYP1B1 L432V missense polymorphism in prostate, bladder and renal cancers. However, the effects of this polymorphism on the risk of these cancers remain conflicting. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the association between L432V polymorphism and the susceptibility of urinary cancers.

Methods

We searched the PubMed database without limits on language for studies exploring the relationship of CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and urinary cancers. Article search was supplemented by screening the references of retrieved studies manually. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to evaluate the strength of these associations. Simultaneously, publication bias was estimated by funnel plot and Begg’s test with Stata 11 software.

Results

We observed a significant association between CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and urinary cancers. The overall OR (95% CI) of CC versus CG was 0.937 (0.881-0.996), the overall OR (95% CI) of CC versus CG + GG was 0.942 (0.890-0.997). Furthermore, we identified reduced risk for CC versus other phenotypes in both prostate and overall urinary cancers, when studies were limited to Caucasian or Asian patients.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggests that the CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism is associated with urinary cancer risk.

Virtual Slides

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here: http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/3108829721231527

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer, urothelial carcinoma and renal cancer are common cancer types and major cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1, 2]. Smoking, diet and environmental factors have been reported to contribute to the carcinogenesis of these malignancies[3, 4]. However, the fact that a small fraction of people exposed to these carcinogens eventually develop urinary cancers suggests that individual genetic predisposition factors may contribute to carcinogenesis.

Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) is a member of the CYP1 gene family and one of the major enzymes involved in the hydroxylation of estrogens, involved in the oxidative activation and deactivation of xenobiotics[5–7]. Several polymorphisms in the CYP1B1 gene have been reported, including 4326C/G (L432V, rs1056836) in exon 3, which encodes the heme-binding domain, have been associated with enhanced catalytic activity when compared to the wild-type allele[8–10].

Polymorphisms in XPC and MHTFR gene have been reported to be associated with overall urinary cancer risk[11, 12], suggesting that urinary cancers share common mechanisms in the process of DNA repair and carcinogen metabolism. Several case–control studies were performed to identify the association of CYP1B1 polymorphisms with prostate, bladder and renal cancer risk. However, small sample sizes and limited populations in study design have often yielded inclusive results among the studies[13–29]. The inconsistent conclusions may have resulted from difference ethnic backgrounds and relatively small sample sizes. To validate the potential association between the CYP1B1 Leu432Val polymorphism and urinary cancer risk, we conducted a meta-analysis of data reported in 17 studies including 7,944 cases and 7,389 controls.

Methods

Publication search

Medline, PubMed, Embase and Web of Science were searched for all relevant articles with the following terms: “Cytochrome P450 1B1” or “CYP1B1”, “polymorphism” or “variant”, “case–control”, “risk”, “association”, “prostate cancer”, “bladder cancer” and “renal cancer” (last search was updated on Feb 10, 2014). References of the retrieved articles on this topic were also manually screened for additional relevant eligible studies.

Selection criteria

We defined inclusion criteria as follows: written in English; case–control design; sufficient information for estimating odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI); observed genotype frequencies in the controls in agreement with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Abstracts and unpublished reports were not considered. Investigations in subjects with family history or cancer-prone disposition were also excluded. Meanwhile, if studies had overlapping subjects, we selected the most recent study that included the largest number of individuals in the publications. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted the following information from each study: the first author, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, source of controls (population-based, hospital-based and mixed controls), genotyping method, number of genotyped cases and controls, number of genotypes for three CYP1B1 polymorphisms in cases and controls, and main findings.

Statistical methods

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was evaluated for each study, using the goodness-of-fit chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered representative of departure from HWE. Crude OR with 95% CI was used to assess the strength of association between the three CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and urinary cancer risk. Then, we calculated the pooled ORs and 95% CIs. Heterogeneity assumption was checked by the chi-square-based Q-test. A P value greater than 0.10 for the Q-test indicates a lack of heterogeneity among studies, so the pooled OR estimate of the each study was calculated by the fixed-effects model (the Mantel–Haenszel method), the random-effects model (the Der-Simonian and Laird method) was used otherwise[30, 31]. To assess the effects of individual studies on the overall risk of cancer, sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding each study at a time individually and recalculating the ORs and 95% CIs. We also used the inverted funnel plot and the Egger’s test to examine the potential influence of publication bias (linear regression analysis). The significance of the intercept was determined by the t-test suggested by Egger (P < 0.05 was considered representative of statistically significant publication bias)[32]. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were performed with STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) or SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results and discussion

Study characteristics

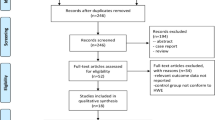

We identified a total of 71 relevant publications after initial screening. Among these, 26 publications had met the inclusion criteria and were subjected to further examination. We excluded 4 publications because they did not present detailed genotyping information. We also excluded 5 publications because they did not include L432V polymorphism. Our final data consisted of 10 publications with a total of 5949 cases and 5388 controls for prostate cancer, 5 publications with 1658 cases and 1593 controls for bladder cancer, 2 publications with 337 cases and 408 controls for renal cancer (Figure 1). Of these, there were 10 hospital-based studies and 7 population-based studies. Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Quantitative synthesis

Table 2 lists the main results of this meta-analysis. Overall, significant associations were found between CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and urinary cancer risk when all studies pooled into the meta-analysis (CC vs CG: OR = 0.937, 95% CI = 0.881-0.996; CC vs CG + GG: OR = 0.942, 95% CI = 0.890-0.997; C vs G: OR = 0.957, 95% CI = 0.917-0.998) (Figure 2). In the subgroup analysis, L432V polymorphism was significantly associated with prostate cancer or overall urinary cancer risk when population was defined as only Caucasians or Asians (Additional file1: Table S1). Nevertheless, when studies were restricted to population-based or hospital-based studies, none of these comparisons showed significant differences. The FPRP values for significant findings at different prior probability levels were also calculated. For a prior probability of 0.1, assuming that the OR for specific genotype was 0.67/1.50 (protection/risk), the FPRP values were 0.786, 0.79 and 0.794 for an association of overall CC vs CG, CC vs CG + GG and C vs G genotypes with an increased lung cancer risk.

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses

Heterogeneities were observed among studies for the association between the CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and urinary cancer risk (CC vs GG, CC vs CG, CC vs CG + GG, C vs G for prostate cancer; C vs G for bladder cancer; CC vs GG, CC vs CG, CC vs CG + GG, C vs G for overall urinary cancers). Therefore, we used the random-effects model that generated wider CIs. For the other groups of comparisons, no heterogeneity was found among studies and the fixed-effects model was performed (Table 2, Additional file1: Table S1). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis indicated that no single study changed the pooled ORs qualitatively (data not shown).

Publication bias

The shapes of the funnel plots seemed symmetrical, and Egger’s test suggested that publication bias was only found in the CC vs GG group of bladder cancer (Table 2, Additional file1: Table S1).

In this meta-analysis, we tested the association between L432V polymorphism in the CYP1B1 gene and urinary cancer risk by comparing the allele frequencies from 17 published studies. We observed a significant association of L432V polymorphism with overall urinary cancer risk, as well as in the subgroups defined as Caucasian or Asian populations. Urinary system tumorigenesis is a complex event, in which different carcinogenic chemicals are involved. Prostate is a hormone-responsive organ in which androgens are believed to stimulate growth and secretory functions. Evidences have been shown that CYP1B1 protein is highly expressed in prostate cancer tissues, while not in normal prostate tissues[33]. It has been reported that different allelic variants of CYP1B1 have different catalytic activities and specificities to procarcinogens, thus partly explains molecular mechanism of CYP1B1 in carcinogenesis[34]. Except for prostate cancer, case–control studies have shown inconsistent associations between CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and bladder cancer and renal cancer risk[24, 28, 29]. However, exact mechanisms of how CYP1B1 polymorphism contributes to urinary cancer susceptibility requires further illustration.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis should be discussed. First, the total number of included studies of bladder cancer and renal cancer was relatively small. Second, our results were based on unadjusted estimates, while a more precise analysis is needed if individual data were available, which would allow for the adjustment by other factors such as age, smoking status, drinking status. Finally, unpublished data may have not been included in the current analysis, potentially causing a bias in the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that the CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism is associated with urinary cancer development, especially in specified Caucasian and Asian populations. However, studies with larger number of samples from homogeneous urinary cancer patients are needed. Further biological investigations may eventually lead to better understanding of the association between the CYP1B1 polymorphism and urinary cancer risk.

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011, 61: 69-90. 10.3322/caac.20107.

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014, 64: 9-29. 10.3322/caac.21208.

Garcia-Closas M, Rothman N, Figueroa JD, Prokunina-Olsson L, Han SS, Baris D, Jacobs EJ, Malats N, De Vivo I, Albanes D, Purdue MP, Sharma S, Fu YP, Kogevinas M, Wang Z, Tang W, Tardón A, Serra C, Carrato A, García-Closas R, Lloreta J, Johnson A, Schwenn M, Karagas MR, Schned A, Andriole G, Grubb R, Black A, Gapstur SM, Thun M, et al.: Common genetic polymorphisms modify the effect of smoking on absolute risk of bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73: 2211-2220. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2388.

Joshi AD, Corral R, Catsburg C, Lewinger JP, Koo J, John EM, Ingles SA, Stern MC: Red meat and poultry, cooking practices, genetic susceptibility and risk of prostate cancer: results from a multiethnic case–control study. Carcinogenesis. 2012, 33: 2108-2118. 10.1093/carcin/bgs242.

Agundez JA: Cytochrome P450 gene polymorphism and cancer. Curr Drug Metab. 2004, 5: 211-224. 10.2174/1389200043335621.

Hayes CL, Spink DC, Spink BC, Cao JQ, Walker NJ, Sutter TR: 17 beta-estradiol hydroxylation catalyzed by human cytochrome P450 1B1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996, 93: 9776-9781. 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9776.

Sutter CH, Qian Z, Hong YP, Mammen JS, Strickland PT, Sutter TR: Genotyping human cytochrome: P450 1B1 variants. Methods Enzymol. 2002, 357: 53-58.

Hanna IH, Dawling S, Roodi N, Guengerich FP, Parl FF: Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) pharmacogenetics: association of polymorphisms with functional differences in estrogen hydroxylation activity. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 3440-3444.

Li DN, Seidel A, Pritchard MP, Wolf CR, Friedberg T: Polymorphisms in P450 CYP1B1 affect the conversion of estradiol to the potentially carcinogenic metabolite 4-hydroxyestradiol. Pharmacogenetics. 2000, 10: 343-353. 10.1097/00008571-200006000-00008.

Shimada T, Watanabe J, Kawajiri K, Sutter TR, Guengerich FP, Gillam EM, Inoue K: Catalytic properties of polymorphic human cytochrome P450 1B1 variants. Carcinogenesis. 1999, 20: 1607-1613. 10.1093/carcin/20.8.1607.

Dou K, Xu Q, Han X: The association between XPC Lys939Gln gene polymorphism and urinary bladder cancer susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2013, 8: 112-10.1186/1746-1596-8-112.

Xu W, Zhang H, Wang F, Wang H: Quantitative assessment of the association between MHTFR C677T (rs1801133, Ala222Val) polymorphism and susceptibility to bladder cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2013, 8: 95-10.1186/1746-1596-8-95.

Holt SK, Kwon EM, Fu R, Kolb S, Feng Z, Ostrander EA, Stanford JL: Association of variants in estrogen-related pathway genes with prostate cancer risk. Prostate. 2013, 73: 1-10. 10.1002/pros.22534.

Catsburg C, Joshi AD, Corral R, Lewinger JP, Koo J, John EM, Ingles SA, Stern MC: Polymorphisms in carcinogen metabolism enzymes, fish intake, and risk of prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012, 33: 1352-1359. 10.1093/carcin/bgs175.

Beuten J, Gelfond JA, Byrne JJ, Balic I, Crandall AC, Johnson-Pais TL, Thompson IM, Price DK, Leach RJ: CYP1B1 variants are associated with prostate cancer in non-Hispanic and Hispanic Caucasians. Carcinogenesis. 2008, 29: 1751-1757. 10.1093/carcin/bgm300.

Berndt SI, Chatterjee N, Huang WY, Chanock SJ, Welch R, Crawford ED, Hayes RB: Variant in sex hormone-binding globulin gene and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16: 165-168. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0689.

Cussenot O, Azzouzi AR, Nicolaiew N, Fromont G, Mangin P, Cormier L, Fournier G, Valeri A, Larre S, Thibault F, Giordanella JP, Pouchard M, Zheng Y, Hamdy FC, Cox A, Cancel-Tassin G: Combination of polymorphisms from genes related to estrogen metabolism and risk of prostate cancers: the hidden face of estrogens. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 3596-3602. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0908.

Sobti RC, Onsory K, Al-Badran AI, Kaur P, Watanabe M, Krishan A, Mohan H: CYP17, SRD5A2, CYP1B1, and CYP2D6 gene polymorphisms with prostate cancer risk in North Indian population. DNA Cell Biol. 2006, 25: 287-294. 10.1089/dna.2006.25.287.

Cicek MS, Liu X, Casey G, Witte JS: Role of androgen metabolism genes CYP1B1, PSA/KLK3, and CYP11alpha in prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14: 2173-2177. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0215.

Fukatsu T, Hirokawa Y, Araki T, Hioki T, Murata T, Suzuki H, Ichikawa T, Tsukino H, Qiu D, Katoh T, Sugimura Y, Yatani R, Shiraishi T, Watanabe M: Genetic polymorphisms of hormone-related genes and prostate cancer risk in the Japanese population. Anticancer Res. 2004, 24: 2431-2437.

Chang BL, Zheng SL, Isaacs SD, Turner A, Hawkins GA, Wiley KE, Bleecker ER, Walsh PC, Meyers DA, Isaacs WB, Xu J: Polymorphisms in the CYP1B1 gene are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003, 89: 1524-1529. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601288.

Tanaka Y, Sasaki M, Kaneuchi M, Shiina H, Igawa M, Dahiya R: Polymorphisms of the CYP1B1 gene have higher risk for prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002, 296: 820-826. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02004-1.

Berber U, Yilmaz I, Yilmaz O, Haholu A, Kucukodaci Z, Ates F, Demirel D: CYP1A1 (Ile462Val), CYP1B1 (Ala119Ser and Val432Leu), GSTM1 (null), and GSTT1 (null) polymorphisms and bladder cancer risk in a Turkish population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013, 14: 3925-3929. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.6.3925.

Salinas-Sanchez AS, Donate-Moreno MJ, Lopez-Garrido MP, Gimenez-Bachs JM, Escribano J: Role of CYP1B1 gene polymorphisms in bladder cancer susceptibility. J Urol. 2012, 187: 700-706. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.063.

Fontana L, Delort L, Joumard L, Rabiau N, Bosviel R, Satih S, Guy L, Boiteux JP, Bignon YJ, Chamoux A, Bernard-Gallon DJ: Genetic polymorphisms in CYP1A1, CYP1B1, COMT, GSTP1 and NAT2 genes and association with bladder cancer risk in a French cohort. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29: 1631-1635.

Figueroa JD, Malats N, Garcia-Closas M, Real FX, Silverman D, Kogevinas M, Chanock S, Welch R, Dosemeci M, Lan Q, Tardón A, Serra C, Carrato A, García-Closas R, Castaño-Vinyals G, Rothman N: Bladder cancer risk and genetic variation in AKR1C3 and other metabolizing genes. Carcinogenesis. 2008, 29: 1955-1962. 10.1093/carcin/bgn163.

Hung RJ, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Malaveille C, Hautefeuille A, Donato F, Gelatti U, Spaliviero M, Placidi D, Carta A, Scotto di Carlo A, Porru S: GST, NAT, SULT1A1, CYP1B1 genetic polymorphisms, interactions with environmental exposures and bladder cancer risk in a high-risk population. Int J Cancer. 2004, 110: 598-604. 10.1002/ijc.20157.

Salinas-Sanchez AS, Sanchez-Sanchez F, Donate-Moreno MJ, Rubio-del-Campo A, Serrano-Oviedo L, Gimenez-Bachs JM, Martinez-Sanchiz C, Segura-Martin M, Escribano J: GSTT1, GSTM1, and CYP1B1 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to sporadic renal cell cancer. Urol Oncol. 2012, 30: 864-870. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.10.001.

Sasaki M, Tanaka Y, Okino ST, Nomoto M, Yonezawa S, Nakagawa M, Fujimoto S, Sakuragi N, Dahiya R: Polymorphisms of the CYP1B1 gene as risk factors for human renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10: 2015-2019. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0166.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Mantel N, Haenszel W: Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959, 22: 719-748.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315: 629-634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Carnell DM, Smith RE, Daley FM, Barber PR, Hoskin PJ, Wilson GD, Murray GI, Everett SA: Target validation of cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 in prostate carcinoma with protein expression in associated hyperplastic and premalignant tissue. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004, 58: 500-509. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.064.

Shimada T, Watanabe J, Inoue K, Guengerich FP, Gillam EM: Specificity of 17beta-oestradiol and benzo[a]pyrene oxidation by polymorphic human cytochrome P4501B1 variants substituted at residues 48, 119 and 432. Xenobiotica. 2001, 31: 163-176. 10.1080/00498250110043490.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Scientific Program of the Department of Education, JiangXi Province, China (GJJ13047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WF J, G S and JH X conceived and performed statistics, WF J, XQ X and ZM S extracted data and wrote the manuscript, G S and ZM S revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13000_2014_986_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1: Subgroup analysis of association between CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism and urinary cancer risk. (DOCX )

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Sun, G., Xiong, J. et al. Association of CYP1B1 L432V polymorphism with urinary cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol 9, 113 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-113

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-113