Abstract

Background

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is an effective therapy to correct for a deficiency of multiple coagulation factors during bleeding. In past years, use of FFP has increased, in particular in patients on the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and has expanded to include prophylactic use in patients with a coagulopathy prior to undergoing an invasive procedure. Retrospective studies suggest that prophylactic use of FFP does not prevent bleeding, but carries the risk of transfusion-related morbidity. However, up to 50% of FFP is administered to non-bleeding ICU patients. With the aim to investigate whether prophylactic FFP transfusions to critically ill patients can be safely omitted, a multi-center randomized clinical trial is conducted in ICU patients with a coagulopathy undergoing an invasive procedure.

Methods

A non-inferiority, prospective, multicenter randomized open-label, blinded end point evaluation (PROBE) trial. In the intervention group, a prophylactic transfusion of FFP prior to an invasive procedure is omitted compared to transfusion of a fixed dose of 12 ml/kg in the control group. Primary outcome measure is relevant bleeding. Secondary outcome measures are minor bleeding, correction of International Normalized Ratio, onset of acute lung injury, length of ventilation days and length of Intensive Care Unit stay.

Discussion

The Transfusion of Fresh Frozen Plasma in non-bleeding ICU patients (TOPIC) trial is the first multi-center randomized controlled trial powered to investigate whether it is safe to withhold FFP transfusion to coagulopathic critically ill patients undergoing an invasive procedure.

Trial Registration

Trial registration: Dutch Trial Register NTR2262 and ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01143909

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is an effective therapy to correct for a deficiency of multiple coagulation factors [1]. International guidelines support its use in case of bleeding in patients with such a deficiency [2, 3]. Use of FFP has grown steadily in the past years, in particular in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) [4]. In the last decade, use of FFP has expanded to include prophylactic administration of FFP. However, there are concerns about the efficacy of FFP to prevent bleeding. Evidence from randomized controlled trials that support FFP transfusion to correct coagulopathy before an invasive procedure is limited, including commonly performed procedures on the ICU, such as insertion of a central venous catheter, a chest drain or a percutaneous tracheotomy [5]. Moreover, retrospective studies suggest that the risk of bleeding after an invasive procedure is low and relevant bleeding requiring blood transfusion or an intervention is less then 1% [6].

Prophylactic FFP may not further reduce bleeding incidence, but carries the risk of acute lung injury, occurring in up to 30% of transfused ICU patients [7], resulting in an increased duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay [8, 9]. However, despite the absence of evidence, in our ICU patients, 33% of plasma is transfused to non-bleeding patients [10], which is in accordance with reports on ICU transfusion practice in Europe and the United States [11, 12].

With the aim to investigate whether prophylactic FFP transfusions to critically ill patients can be safely omitted, a multi-center randomized clinical trial is conducted in ICU patients with a coagulopathy undergoing an invasive procedure.

Methods/Design

Objectives and design

The primary objective of the 'Transfusion of fresh frozen Plasma In non-bleeding Critically ill' trial ('TOPIC' trial) is to assess whether omitting prophylactic FFP transfusion is non-inferior to prophylactic FFP transfusion (current practice) to prevent relevant bleeding in ICU patients with a coagulopathy, who are undergoing an invasive procedure.

The preferred design to demonstrate the non-inferiority of no FFP transfusion prior to an invasive procedure against FFP transfusion to prevent bleeding would be a double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. However, manufacturing a completely matched placebo in full compliance with the current Good Manufacturing Practice standards was not considered possible for this non-commercial, academic study. Therefore, we have chosen for a multicentre prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded end point evaluation (PROBE) design.

The Institutional Review Board of the Academic Medical Center - University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, approved the trial. The TOPIC trial is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered on March 26 2010 at http://www.trialregister.nl with trial identification number NTR2262 and on June 14 2010 at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov with trial identification number NCT01143909.

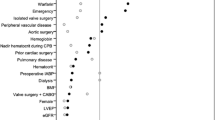

Consort Diagram

Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram of the TOPIC trial.

Study population

The source population consists of patients admitted to medical-surgical ICUs, who have a prolonged International Normalized Ratio (INR) and will undergo an invasive procedure. Based on previous reports, we expect that 30% of ICU patients have a prolonged INR [13]. A total of 400 patients will be randomized to omitting FFP or receiving 12 ml/kg FFP before a scheduled intervention. Local investigators will screen consecutive patients with a prolonged INR, which is determined daily in all ICU patients. Patients with an INR ≥ 1.5 and ≤ 3.0, who are 18 years and older and will be undergoing an invasive procedure, are eligible. Defined invasive procedures are insertion of a central venous catheter, thoracocentesis, percutaneous tracheotomy or drainage of abscess or fluid collection.

Patients with clinically overt bleeding, e.g. with decrease of hemoglobin > 1 mmol/L, needing transfusion or hemodynamic instability due to bleeding at the time of the procedure or with a thrombocytopenia of < 30 × 109/L are excluded from participation. Also, patients are excluded if they are treated with vitamin K antagonists, activated protein C, abciximab, tirofiban, ticlopidine, low molecular weight heparin (therapeutic dosage), heparin or prothrombin complex concentrates. In addition, patients with a history of congenital or acquired coagulation factor deficiency or bleeding diathesis are excluded. Patients will only be included after informed consent from the patient, his/her (legal) representative or the closest relative has been obtained.

Randomization and intervention

Patients are randomly assigned to receive or not to receive a single dose of 12 ml/kg FFP. The randomization procedure is password protected, web-based, using permuted blocks and stratified by study centre and invasive procedure. Patients can only be randomized once (e.g. for one procedure). The units of FFP will be ordered from Sanquin, the Dutch National Bloodbank. The chosen amount of 12 ml/kg will lead to an estimated reduction of INR to 1.4 - 1.6.

Standard procedures

The predetermined invasive procedures are placement of any central venous catheter, percutaneous tracheostomy, thoracocentesis and percutaneous drainage of any fluid collection or abscess. Clinical practices, such as using ultrasound guidance when inserting a central venous catheter, are applied according to each centers specific expertise and routine, to minimize interference of the trial intervention with normal clinical practice.

Protocol drop out

Subjects can leave the study at any time for any reason if they wish to do so without any consequences. The investigator can decide to withdraw a subject from the study for urgent medical reasons. In patients who develop an acute reaction (increase in body temperature of more than 2°C, hypotension, bronchospasm or development of urticaria), the transfusion will be stopped immediately and adequate clinical measures will be taken accordingly With an incidence of transfusion reaction of 0.1- 1% [3], we expect little drop-outs. Unless patients declare that collected data need to be discarded, data of dropped out participants will be included in the intention to treat analysis.

Rescue therapy

FFPs will be ordered (but not thawed) from the blood transfusion laboratory also for the patients randomized to the arm with no transfusion. When a relevant bleeding occurs during or after the procedure, these blood products will be readily at hand to be administered.

Study end points

The primary outcome of this study will be a procedure-related relevant bleeding, occurring within 24 hours after the procedure. Relevant bleeding is defined using a validated tool (HEME) in the critically ill [14]: overt bleeding with any of the following: a decrease in hemoglobin by more then 2 g/dL (1.2 mmol/L) in the absence of another cause or transfusion of 2 or more units red cells without an increase in hemoglobin or a decrease in systolic blood pressure by more then 20 mmHg, or an increase in heart rate by 20 beats per minute or more, or bleeding at a insertion or wound site requiring an intervention. Interventions to cease bleeding are defined as an extra suture at the insertion site, embolization by an intervention radiologist or any surgical intervention required to stop the bleeding. The primary end point will be assessed by a physician who is blinded for the randomization result at 1 and 24 hours after the intervention.

Secondary endpoints include the occurrence of minor bleeding (e.g. prolonged bleeding at the insertion site or increase in size of subcutaneous hematoma), the development of ALI and circulatory overload. For this purpose the Lung Injury Score will be calculated at 24 hours. This score includes chest radiographic score, hypoxemia score (PaO2/FiO2), positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) level (cm H2O), and respiratory system compliance score when available [15]. According to the definition, circulatory overload can be defined as bilateral edema on chest x-ray and a wedge pressure > 18 mmHg. In patients who will not have a SwanGanz catheter in place, circulatory overload will be defined as pulmonary edema in the presence of at least 3 of the following: positive fluid balance, elevated central venous pressure, a history of heart failure and increase in oxygenation in response to diuretics. Furthermore, the effect of FFP on correction of INR and clotting variables and the effect of FFP transfusion on outcome (duration of mechanical ventilation, length of ICU stay and ICU mortality) will be evaluated.

Other variables that are collected include demographics, co-morbidities, severity of illness (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation IV, APACHE IV [16]), medication use, hemodynamic and respiratory data (from the electronic patient data monitoring system). Blood samples will be drawn to determine coagulation variables, hemoglobin, blood gas analysis and liver- and renal function.

After the invasive procedure has been completed, repeated assessments will be made after 1 and 24 hours. These will include registration of hemodynamic and respiratory data from the Patient Data Management System (PDMS), a limited physical examination (inspection of the insertion site of the catheter or drain), inspection of drain production, and collection of a blood sample to perform blood gas analysis and assess hemoglobin levels. The limited physical examination will be done by an independent physician blinded for the randomization group. A chest radiograph will be performed 24 hours after the procedure.

Statistical considerations

A systematic search of the literature showed that the occurrence of a relevant bleeding (resulting in shock or requiring blood transfusion or intervention) in patients with a coagulopathy undergoing invasive procedures is 0.1 - 0.8% [17–24]. Hence, it is expected that in 99% of the patients no major bleeding will occur under prophylactic FFP transfusion and that there will be no increase in the incidence of major bleedings in case no prophylactic FFP transfusion is given. Group size calculation is focused on demonstrating non-inferiority. When the sample size in each group is 198, a one-sided Z test with continuity correction (pooled) achieves 80% power to reject the null hypothesis that the proportion of bleeding patients in the experimental group (no FFP transfusion) is 0.04 or higher, i.e. is inferior to the proportion in the control group (FFP transfusion) by a safety margin of 0.03, in favor of the alternative hypothesis that the proportion in the experimental group is non-inferior. It is assumed that the expected difference in proportions is zero and the proportion in the control group is 0.01. The one-sided significance level of the test was targeted at 0.05. Based on our pilot trial, we expect that all included patients are available for evaluation at the end of the study. Therefore, we intend to enroll 200 patients per treatment arm: 400 patients in total.

Statistical analysis

Baseline assessments and outcome parameters will be summarized using simple descriptive statistics. Variables will be expressed by their mean and standard deviation if normally distributed, if not normally distributed they will be expressed by their medians and interquartile ranges. The main analysis focuses on a comparison between the trial treatment groups of the primary outcome, the occurrence of relevant bleedings (using a binary variable), expressed in a relative risk estimate and absolute risk increase. In case of clinically relevant baseline imbalances, the primary outcome will be additionally analyzed using multivariate Poisson or logistic regression, when appropriate.

Secondary outcome parameters such as coagulation variables, acute lung injury, number of ventilation days and length of ICU stay will be expressed using continuous variables. Minor bleedings, occurrence of acute lung injury and serious adverse events will be expressed as binary variables (any versus none). The secondary outcome parameters will be analyzed using the Chi-square test (including RR estimates), two group t-test or Mann-Whitney test, when appropriate. In all analyses statistical uncertainties will be expressed in 95% confidence limits.

Because of the non-inferiority design of the trial, both an intention to treat analysis as well as a per-protocol analysis will be done.

Study organization

The study principal investigator coordinates the study together with the local investigator of the Academic Medical Center. Each participating center has its own local principal investigator who all approved the final trial design and protocol.

This study is considered a low risk trial, in which current practice, transfusion of FFP, with known side effects, is compared to omitting FFP. However, an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) is instituted and monitors patient safety during the study.

Any serious adverse event (SAE) will be reported to the Institutional Review Board of the Academic Medical Center - University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands and the DSMB. A predefined list of SAEs will be listed and reported periodically instead of individually, including transfusion reactions and minor bleeding not requiring an intervention.

Discussion

Coagulopathy is highly prevalent in critically ill patients. An INR of > 1.5 occurs in 30% of patients and is associated with increased mortality [13]. Risk factors for coagulopathy are sepsis, liver disease, multiple blood transfusions and trauma [13, 25]. Coagulopathy results from an imbalance between activation of coagulation and impaired inhibition of coagulation and fibrinolysis. The disturbance between these components of the coagulation system leads to a variable clinical picture, ranging from patients with an increased bleeding tendency ("consumption coagulopathy") to those with diffuse intravascular coagulation (DIC) with (micro-) vascular thrombosis. However, clinical assessment of coagulation status and bleeding tendency in these patients is complex and the ability of global coagulation tests to accurately reflect in vivo coagulation is questioned [26]. In daily clinical practice, the INR, although initially developed to monitor warfarin therapy, is one of the commonly used tests to assess coagulopathy. In ICU patients, the majority indeed has a prolonged INR [10, 11, 13].

ICU patients frequently undergo invasive procedures, which carry the risk of bleeding. However, the incidence of bleeding after an invasive procedure in patients with a prolonged INR is low. It is shown that central venous catheter placement can be safely done in coagulopathic patients, without the need to correct coagulation abnormalities [19, 21]. The incidence of major bleeding, requiring transfusion of red blood cells, ranges from 0.1-0.8%, of minor bleeding from 2.2-6% [20, 22, 27]. Studies on the safety of performing a percutaneous tracheostomy in patients with a prolonged INR report no evidence of major bleeding [28]. After thoracocentesis, the risk of relevant bleeding is 0.2% and the risk of minor bleeding is 2.6% [29].

Use of FFP to correct for a deficiency of multiple coagulation factors in case of bleeding [1] is supported by many international guidelines [3, 30]. However, efficacy of the use of prophylactic FFP in non-bleeding patients is uncertain [31]. Although consensus regarding profylactic use is lacking, 30-50% of FFP units are administered to non bleeding patients [10, 13, 32]. There are important variations in ICU clinicians' beliefs and practices in relation to FFP treatment of non-bleeding coagulopathic critically ill patients [12, 32, 33]. Also, the dose of FFP administered varies widely, ranging from 7.2 to 14.4 ml/kg [32]. Studies on transfusion practice point to the assumption of ICU physicians that FFP corrects clinically relevant coagulopathy, thereby preventing bleeding [34].

FFP can correct a prolonged INR in critically ill patients, but most studies show a reduction and not a complete normalization of INR [1, 7, 35, 36]. A minimally elevated INR (up to 1.5) cannot be corrected, even with higher doses of FFP [37, 38]. When INR is > 1.5, a relationship between dose and target INR is found [1, 38]. Studies on the dose of FFP to correct INR in ICU patients show conflicting results. Two randomized controlled trials (RCT) in ICU patients have been done. A small study showed that 33 ml/kg was more effective in achieving target levels of coagulation factors compared to 12 ml/kg [1]. However, the range of dosage in this study was wide and an association with bleeding was not studied. In a larger RCT in ICU patients, 20 ml/kg did not differ from 12 ml/kg in correction of INR or increasing coagulation factors above a minimum haemostatic threshold [35]. As complete correction of INR is not a target in this trial, because a mild prolonged INR (< 1.5) is not considered a risk of bleeding [6, 37], we chose the dose of 12 ml/kg FFP for the control group. In addition, transfusion with higher doses of FFP is not current practice (own data and [12, 32]) and may hamper compliance of physicians to the study protocol.

In recent years, many reports have been published on the detrimental effects of FFP. It is well shown that FFP transfusion is an independent risk factor for new onset of acute lung injury [39–45], in particular in patients who are mechanically ventilated [46]. Furthermore, studies consistently report a significant increase in length of ICU stay [34, 44, 46].

The TOPIC trial aims to demonstrate that omitting prophylactic FFP transfusion in coagulopathic critically ill patients undergoing an invasive procedure is safe in terms of bleeding complications. Recently, one other trial with similar purposes has been completed (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00953901), but results have not been published yet. Of note, in this trial, all hospitalized patients were eligible, in contrast to our trial which focuses on ICU patients. Recently, a trial on the effectiveness of FFP in critically ill has been completed (EPICC trial http://www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00302965), not merely studying the effect of prophylactic FFP use since also active bleeding patients have been included in this study,.

A limitation of our trial is that it is not a double blind placebo controlled trial. However, manufacturing a completely matched placebo was considered not feasible for this non-commercial, academic study. The chosen PROBE design has the advantages of lower costs and greater similarity to standard clinical practice. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that the reliability of end-point evaluation would differ between a PROBE study and a double-blind study, provided that the same criteria are applied [47]. In addition, it is shown that results from double-blind, placebo-controlled and PROBE trials are statistically comparable [48].

Former studies on the efficacy of FFP have been criticized by using irrelevant end-points, such as correction of INR [6]. The primary outcome of this study will be a procedure-related relevant bleeding, occurring within 24 hours after the procedure as assessed by the HEME tool [14]. A possible disadvantage of the tool is that some items scored with the HEME tool, such as decrease in systolic blood pressure or increase in heart rate, may also occur in the absence of bleeding. However, the inter-rater agreement and agreement between raters on bleeding severity assessments using the HEME tool was shown to be very high (φ = 0.99 (95% CI 0.97-0.99 and φ = 0.98 (95% CI 0.96-0.99 respectively) [14].

In conclusion, the TOPIC trial is a multi-center randomized trial, powered to test the hypothesis that omitting prophylactic FFP prior an intervention in critically ill patients with a coagulopathy is safe and is not associated with increased bleeding complications. In addition, the TOPIC trial determines the effect of FFP on correction of coagulopathy and evaluates the potential detrimental effects of FFP in this patient group.

Trial status

The trial is currently ongoing; we expect to complete patient recruitment in 2013.

Abbreviations

- ALI:

-

Acute Lung Injury

- APACHE IV:

-

Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation IV score

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DSMB:

-

Data Safety Monitoring Board

- FFP:

-

Fresh Frozen Plasma

- HEME:

-

HEmorrhage MEasurement

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- INR:

-

International Normalized Ratio

- PDMS:

-

Patient Data Monitoring System

- PROBE:

-

Prospective Randomized Open-label Blinded-End point

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- RR:

-

Relative Risk

- SAE:

-

Serious Adverse Event

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TISS:

-

Therapeutic Intervention Score System

References

Chowdhury P, Saayman AG, Paulus U, Findlay GP, Collins PW: Efficacy of standard dose and 30 ml/kg fresh frozen plasma in correcting laboratory parameters of haemostasis in critically ill patients. Br J Haematol. 2004, 125: 69-73. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04868.x.

Gunter P: Practice guidelines for blood component therapy. Anesthesiology. 1996, 85: 1219-1220.

O'Shaughnessy DF, Atterbury C, Bolton MP, Murphy M, Thomas D, Yates S, Williamson LM: Guidelines for the use of fresh-frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate and cryosupernatant. Br J Haematol. 2004, 126: 11-28.

Wallis JP, Dzik S: Is fresh frozen plasma overtransfused in the United States?. Transfusion. 2004, 44: 1674-1675. 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.00427.x.

Stanworth SJ, Brunskill SJ, Hyde CJ, McClelland DB, Murphy MF: Is fresh frozen plasma clinically effective? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Haematol. 2004, 126: 139-152. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04973.x.

Holland L, Sarode R: Should plasma be transfused prophylactically before invasive procedures?. Curr Opin Hematol. 2006, 13: 447-451. 10.1097/01.moh.0000245688.47333.b6.

Dara SI, Rana R, Afessa B, Moore SB, Gajic O: Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in critically ill medical patients with coagulopathy. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 2667-2671. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000186745.53059.F0.

Gajic O, Rana R, Winters JL, Yilmaz M, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, O'Byrne MM, Evenson LK, Malinchoc M, DeGoey SR, Afessa B, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB: Transfusion-related acute lung injury in the critically ill: prospective nested case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 176: 886-891. 10.1164/rccm.200702-271OC.

Vlaar AP, Binnekade JM, Prins D, van SD, Hofstra JJ, Schultz MJ, Juffermans NP: Risk factors and outcome of transfusion-related acute lung injury in the critically ill: a nested case-control study. Crit Care Med. 2010, 38: 771-778. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc4d4b.

Vlaar AP, in der Maur AL, Binnekade JM, Schultz MJ, Juffermans NP: A survey of physicians' reasons to transfuse plasma and platelets in the critically ill: a prospective single-centre cohort study. Transfus Med. 2009, 19: 207-212. 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00928.x.

Dzik W, Rao A: Why do physicians request fresh frozen plasma?. Transfusion. 2004, 44: 1393-1394. 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.00422.x.

Watson DM, Stanworth SJ, Wyncoll D, McAuley DF, Perkins GD, Young D, Biggin KJ, Walsh TS: A national clinical scenario-based survey of clinicians' attitudes towards fresh frozen plasma transfusion for critically ill patients. Transfus Med. 2011, 21: 124-129. 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2010.01049.x.

Walsh TS, Stanworth SJ, Prescott RJ, Lee RJ, Watson DM, Wyncoll D: Prevalence, management, and outcomes of critically ill patients with prothrombin time prolongation in United Kingdom intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2010, 38: 1939-1946.

Arnold DM, Donahoe L, Clarke FJ, Tkaczyk AJ, Heels-Ansdell D, Zytaruk N, Cook R, Webert KE, McDonald E, Cook DJ: Bleeding during critical illness: a prospective cohort study using a new measurement tool. Clin Invest Med. 2007, 30: E93-102.

Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR: An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988, 138: 720-723.

Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34: 1297-1310. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215112.84523.F0.

Al DA, Haddad S, Arabi Y, Dabbagh O, Cook DJ: The safety of percutaneous tracheostomy in patients with coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2007, 19: 37-49.

Auzinger G, O'Callaghan GP, Bernal W, Sizer E, Wendon JA: Percutaneous tracheostomy in patients with severe liver disease and a high incidence of refractory coagulopathy: a prospective trial. Crit Care. 2007, 11: R110-10.1186/cc6143.

Doerfler ME, Kaufman B, Goldenberg AS: Central venous catheter placement in patients with disorders of hemostasis. Chest. 1996, 110: 185-188. 10.1378/chest.110.1.185.

Fisher NC, Mutimer DJ: Central venous cannulation in patients with liver disease and coagulopathy--a prospective audit. Intensive Care Med. 1999, 25: 481-485. 10.1007/s001340050884.

Foster PF, Moore LR, Sankary HN, Hart ME, Ashmann MK, Williams JW: Central venous catheterization in patients with coagulopathy. Arch Surg. 1992, 127: 273-275. 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420030035006.

Goldfarb G, Lebrec D: Percutaneous cannulation of the internal jugular vein in patients with coagulopathies: an experience based on 1,000 attempts. Anesthesiology. 1982, 56: 321-323. 10.1097/00000542-198204000-00021.

Kluge S, Meyer A, Kuhnelt P, Baumann HJ, Kreymann G: Percutaneous tracheostomy is safe in patients with severe thrombocytopenia. Chest. 2004, 126: 547-551. 10.1378/chest.126.2.547.

Pandit RA, Jacques TC: Audit of over 500 percutaneous dilational tracheostomies. Crit Care Resusc. 2006, 8: 146-150.

Talving P, Benfield R, Hadjizacharia P, Inaba K, Chan LS, Demetriades D: Coagulopathy in severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2009, 66: 55-61. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318190c3c0.

Levi M, Meijers JC: DIC: which laboratory tests are most useful. Blood Rev. 2011, 25: 33-37. 10.1016/j.blre.2010.09.002.

Mumtaz H, Williams V, Hauer-Jensen M, Rowe M, Henry-Tillman RS, Heaton K, Mancino AT, Muldoon RL, Klimberg VS, Broadwater JR, Westbrook KC, Lang NP: Central venous catheter placement in patients with disorders of hemostasis. Am J Surg. 2000, 180: 503-505. 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00552-3.

Rosseland LA, Laake JH, Stubhaug A: Percutaneous dilatational tracheotomy in intensive care unit patients with increased bleeding risk or obesity. A prospective analysis of 1000 procedures. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011, 55: 835-841. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02458.x.

McVay PA, Toy PT: Lack of increased bleeding after paracentesis and thoracentesis in patients with mild coagulation abnormalities. Transfusion. 1991, 31: 164-171. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31291142949.x.

Iorio A, Basileo M, Marchesini E, Materazzi M, Marchesi M, Esposito A, Palazzesi GP, Pellegrini L, Pasqua BL, Rocchetti L, Silvani CM: The good use of plasma. A critical analysis of five international guidelines. Blood Transfus. 2008, 6: 18-24.

Stanworth SJ, Grant-Casey J, Lowe D, Laffan M, New H, Murphy MF, Allard S: The use of fresh-frozen plasma in England: high levels of inappropriate use in adults and children. Transfusion. 2011, 51: 62-70. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02798.x.

Stanworth SJ, Walsh TS, Prescott RJ, Lee RJ, Watson DM, Wyncoll D: A national study of plasma use in critical care: clinical indications, dose and effect on prothrombin time. Crit Care. 2011, 15: R108-10.1186/cc10129.

Veelo DP, Dongelmans DA, Phoa KN, Spronk PE, Schultz MJ: Tracheostomy: current practice on timing, correction of coagulation disorders and peri-operative management - a postal survey in the Netherlands. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007, 51: 1231-1236. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01430.x.

Lauzier F, Cook D, Griffith L, Upton J, Crowther M: Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35: 1655-1659. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269370.59214.97.

Tinmouth A, Chatelain E, Fergusson D, McIntyre L, Giulivi A, Hebert P: A Randomized Controlled Trial of High and Standard Dose Fresh Frozen Plasma Transfusions in Critically Ill Patients. Transfusion. 2008, 48: 26A-27A.

Abdel-Wahab OI, Healy B, Dzik WH: Effect of fresh-frozen plasma transfusion on prothrombin time and bleeding in patients with mild coagulation abnormalities. Transfusion. 2006, 46: 1279-1285. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00891.x.

Holland LL, Foster TM, Marlar RA, Brooks JP: Fresh frozen plasma is ineffective for correcting minimally elevated international normalized ratios. Transfusion. 2005, 45: 1234-1235. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00184.x.

Holland LL, Brooks JP: Toward rational fresh frozen plasma transfusion: The effect of plasma transfusion on coagulation test results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006, 126: 133-139. 10.1309/NQXHUG7HND78LFFK.

Gajic O, Dara SI, Mendez JL, Adesanya AO, Festic E, Caples SM, Rana R, St Sauver JL, Lymp JF, Afessa B, Hubmayr RD: Ventilator-associated lung injury in patients without acute lung injury at the onset of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004, 32: 1817-1824. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000133019.52531.30.

Khan H, Belsher J, Yilmaz M, Afessa B, Winters JL, Moore SB, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O: Fresh-frozen plasma and platelet transfusions are associated with development of acute lung injury in critically ill medical patients. Chest. 2007, 131: 1308-1314. 10.1378/chest.06-3048.

Gajic O, Dzik WH, Toy P: Fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusion for nonbleeding patients in the intensive care unit: benefit or harm?. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34: S170-S173. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214288.88308.26.

Gajic O, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kor DJ, Winters JL, Moore SB, Afessa B: Transfusion from male-only versus female donors in critically ill recipients of high plasma volume components. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35: 1645-1648. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269036.16398.0D.

Wright SE, Snowden CP, Athey SC, Leaver AA, Clarkson JM, Chapman CE, Roberts DR, Wallis JP: Acute lung injury after ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: the effect of excluding donations from females from the production of fresh frozen plasma. Crit Care Med. 2008, 36: 1796-1802. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181743c6e.

Rana R, Fernandez-Perez ER, Khan SA, Rana S, Winters JL, Lesnick TG, Moore SB, Gajic O: Transfusion-related acute lung injury and pulmonary edema in critically ill patients: a retrospective study. Transfusion. 2006, 46: 1478-1483. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00930.x.

Jia X, Malhotra A, Saeed M, Mark RG, Talmor D: Risk factors for ARDS in patients receiving mechanical ventilation for > 48 h. Chest. 2008, 133: 853-861. 10.1378/chest.07-1121.

Gajic O, Rana R, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, Lymp JF, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB: Acute lung injury after blood transfusion in mechanically ventilated patients. Transfusion. 2004, 44: 1468-1474. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04053.x.

Hansson L, Hedner T, Dahlof B: Prospective randomized open blinded end-point (PROBE) study. A novel design for intervention trials. Prospective Randomized Open Blinded End-Point. Blood Press. 1992, 1: 113-119. 10.3109/08037059209077502.

Smith DH, Neutel JM, Lacourciere Y, Kempthorne-Rawson J: Prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint (PROBE) designed trials yield the same results as double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with respect to ABPM measurements. J Hypertens. 2003, 21: 1291-1298. 10.1097/00004872-200307000-00016.

Acknowledgements

Funding source

This study is an investigator-initiated trial, funded by ZonMw Netherlands Organisation for Health, Research and Development, The Hague, The Netherlands and the Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MM and NJ: preparation of the initial drafts of the manuscript and preparation of the final version. All: review of the initial drafts of the manuscript. NJ and MM designed the study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, M.C., de Jonge, E., Arbous, M.S. et al. Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma in non-bleeding ICU patients -TOPIC TRIAL: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 12, 266 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-12-266

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-12-266