Abstract

A large volume of human clinical data supports increased dietary protein for favorable changes to body composition, but not all data are conclusive. The aim of this review is to propose two theories, “protein spread theory” and “protein change theory” in an effort to explain discrepancies in the literature. Protein spread theory proposed that there must have been a sufficient spread or % difference in g/kg/day protein intake between groups during a protein intervention to see body composition and anthropometric differences. Protein change theory postulated that for the higher protein group, there must be a sufficient change from baseline g/kg/day protein intake to during study g/kg/day protein intake to see body composition and anthropometric benefits. Fifty-one studies met inclusion criteria. In studies where a higher protein intervention was deemed successful there was, on average, a 58.4% g/kg/day between group protein intake spread versus a 38.8% g/kg/day spread in studies where a higher protein diet was no more effective than control. The average change in habitual protein intake in studies showing higher protein to be more effective than control was +28.6% compared to +4.9% when additional protein was no more effective than control. Providing a sufficient deviation from habitual intake appears to be an important factor in determining the success of additional protein in weight management interventions. A modest increase in dietary protein favorably effects body composition during weight management interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Annual healthcare costs relating to obesity approximate $150 billion in the US alone[1]. Thus, there would be great utility for dietary strategies that require minimal restriction yet benefit body composition and metabolic health. Manipulation of dietary macronutrient intake in favor of protein has shown considerable promise since the 1990s[2] and has gained increasing support recently[3–7].

In the US, the Food and Nutrition Board provides a dietary protein recommendation for adults of 0.8 g/kg/day known as the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends 0.83 g/kg/day of high quality protein[8]. Multiple researchers support the consumption of greater protein than the RDA, arguing that the RDA is a minimum level for health, not an optimal intake for health indicators such as body composition[9, 10] something the WHO also notes[8]. Still, there is resistance to recommending a higher amount of protein to the public.

While some will critique that the satiating effect of higher dietary protein sometimes results in voluntary hypophagia[11], leading to an energy intake discrepancy between groups, there is evidence that increased dietary protein leads to improved body composition and anthropometrics under iso-, hypo-, and hyper-caloric conditions[2, 11–44]. Thus, the traditional dogma of “energy in versus energy out” explaining weight and body compositional change is not entirely accurate. Another critique is that there are some studies in which greater protein is no more effective than control[45–60]. These studies do not find negative effects on body composition from higher protein, rather benefits are shown that are the same, but no greater than in controls[45–60]. There has been little examination of why discrepancies in the protein and weight management literature exist.

Due primarily to limitations of dietary adherence in free-living adults, spread, or difference, in protein intake between groups during a study is often less than originally designed[45, 46, 57, 61]. While this would seem an intuitive explanation for why some studies do not show greater body composition and anthropometric benefits of higher protein intakes it seems to have been largely overlooked until recently[62]. One purpose of the present review is to expand upon this observation in methodological critique we have coined protein spread theory.

Additionally, the body’s response to protein is not static, but adjusts to the diet it is afforded[63–65]. For example, progressive increases in protein intake are coupled with increased fasting nitrogen losses[66, 67] along with an increase in feeding induced nitrogen accrual[66, 67] that is perhaps even more pronounced than fasting losses[66]. Although not fully elucidated, a possible implication of this might be an effect on lean tissue mass. A few studies specifically address change in habitual protein intake. Soenen et al. had participants increase habitual protein intake 16%, from 1.13 g/kg/day to 1.31 g/kg/day via substitution of ~500 kcal with a milk protein based supplement containing 52 g protein. Over 12 weight-stable wk this led to 0.7 kg greater lean mass gain and fat loss compared to isoenergetic controls[68]. Bray et al. reported that increasing a 1.2 g/kg/day protein intake to ≥ 1.8 g/kg/day via overfeeding led to an ~3.5-4 kg greater gain in lean body mass in eight wk[69]. Additionally, Petzke et al. reported a positive correlation (r = 0.643, p = 0.0001) between change in habitual protein intake and change in fat-free body mass[70]. While the aforementioned data point to a dynamic response to dietary protein intake it is difficult to extrapolate these findings from a healthy population to the obese. Thus, the second purpose of this review was to propose and examine protein change theory in effort to extend these findings. Objectives of protein change theory are to 1) critique the failure to assess baseline dietary intake in many studies; 2) critique what we feel in an overemphasis on % energy from protein 3) increase recognition that the response of an individual to a diet is influenced by their previous dietary exposures.

Methods

Protein spread theory postulated that there must have been a sufficient spread or% difference in g/kg/day protein intake between groups during a protein intervention to see anthropometric differences. Protein change theory postulated that for the higher protein group, there must be a sufficient change from baseline g/kg/day protein intake to during study g/kg/day protein intake to see anthropometric benefits. Given variety of outcome measures reported in studies in this review (Table1) categorization was necessary. “Anthropometric benefits” referred to herein are: weight loss, body-fat loss, waist circumference reduction, regional body-fat loss, lean mass preservation, decreased weight regain, decreased fat regain, or lean mass gain.

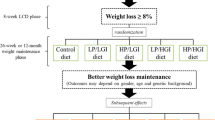

Keyword searches in the PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL databases were conducted up to July 2012 using the search criteria in Figure1. The protein spread theory portion (Table2) of this review examined weight loss trials with a protein intervention, weight loss trials followed by a weight maintenance period incorporating a protein intervention, and protein interventions that spanned both weight loss and weight maintenance periods. Only weight loss studies were examined in the protein change analysis (Tables3 &4). Including weight maintenance studies would introduce a brief period where participants’ metabolisms had to adjust to an atypical intake, making “habitual protein intake” leading into the protein intervention difficult to define. Only two cross-over studies[38, 56] were designed such that the habitual intake of participants prior to intervention could be determined and thus could be included in the change analysis. See the legend of Table1 for more on study categorization.

The following were reasons for exclusion from this review: 1) examination of total protein intake not part of design (focus was on another macronutrient or timing/type of protein was manipulated in a manner not intended to effect total protein intake); 2) energy deficit not incorporated or not incorporated in both groups; 3) non-overweight/obese population; 4) significant differences in baseline anthropometrics; 4) poor dietary control or reporting; 5) < 4 wk; 6) exercise or lifestyle intervention employed not consistent between groups; 7) duplicate of another included study reporting different data sets; 8) participants with conditions not necessarily related to obesity (gout, heart failure, polycystic ovarian syndrome, AIDS, post-pregnancy or bariatric surgery, etc.). This review focused on data from the past two decades (1992-present). A recent meta-regression encompassing 1936–2005 concluded that a greater intake of dietary protein enhances maintenance of lean mass by ~0.6 to 1.2 kg during weight loss. See the analysis by Krieger et al.[3] for further reading.

Based upon the aforementioned criteria, 51 studies were reviewed (Table1). Protein intake is related to body composition and metabolic health, and the RDA is a minimum needed for health in these areas. Thus, the inadequate protein consumed by participants (as defined by the RDA) in the lower protein group of some studies may be viewed by some scientists as creating easier circumstances for a higher protein group to see improved anthropometrics vs. this sub-optimal protein group. For this reason, study groups in which intake of the lower protein group was at or above 0.79 g/kg/day were isolated in a subsequent reanalysis. Given rounding in the calculation methods that follow, studies with a lower protein group at 0.79 g/kg/day were included as meeting the RDA.

Although not perfect, dietary recalls can be reliable in classifying macronutrient intakes[71]. Data from dietary recalls and weighed food records were used for consistency, as this was the form of protein intake reporting used in all studies. Studies using only food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) were excluded. Only some studies provided urine marker derived protein intakes. Some studies provided protein intake data in g/kg/day terms. When only% energy from protein was provided, calculations using energy intake were made to convert this value into g/kg/day. Evidence was examined in a g/kg/day fashion for a more stable comparison across variations of body mass and intakes between studies.

When only g protein/day was provided, baseline body mass was the devisor, yielding g/kg/day. Some studies providing protein intake in g/kg/day terms calculated using baseline body mass while others used post-weight loss body mass. For these studies, the authors manually derived g/kg/day protein intakes using baseline body mass for consistency. Energy intakes provided in mega joules or kilojoules were converted to kilocalories. Dietary intake data sets for multiple time points were often combined as a composite and are noted (Table1).

The term “higher protein” was used to describe the group that had a “higher” protein intake relative to a “lower” protein group, sometimes referred to as a “control” group. “Higher” and “lower” were relative, not denoting a specific intake.

“Spread” calculations for protein spread theory were calculated by:

Between group% spread in protein intake = [((higher protein group g/kg/day intake during study - control group g/kg/day intake during study)/control group g/kg/day intake during study) × 100]

“Change in habitual protein intake” calculations were calculated by:

Change in habitual protein intake = [((g/kg/day intake during study – g/kg/day intake at baseline)/g/kg/day intake at baseline) × 100]

For both theories, after values were obtained for each study, means of particular groups of studies (Figure1) were calculated. Baseline intake refers to g/kg/day protein intake prior to protein intervention.

Results

Thirty-five of the 51 studies examined showed superior body composition and anthropometric benefits of a higher protein intake over control. However, sixteen studies showed no greater body composition and anthropometric benefits of a higher protein intake compared to control. We proposed protein spread theory and protein change theory as possible explanations for this discrepancy.

Protein spread theory

Within 35 studies showing anthropometric benefits of higher protein, g/kg/day intake was 58.4% greater than control on average (Table2). Within 16 studies showing no additional anthropometric benefits of higher protein, g/kg/day intake was only 38.8% greater than control on average.

Since some scientists may find excluding studies with a sub-RDA lower protein group a more balanced analysis of protein spread theory, a reanalysis was performed including only the 27 studies that met RDA inclusion criteria. The 27 were divided into: 1) those 17 showing additional benefit to increased protein and 2) those 10 that did not (Figure2). This additional analysis supported protein spread theory as the mean spread in g/kg/day protein intake in the 17 studies showing a benefit of increased protein was 52%. This was close to the 58.4% figure from the original analysis (Table2). Similarly, the mean spread in the 10 studies showing no additional benefit of increased protein was 30.3%. This was close to the 38.8% figure from the original analysis and supported protein spread theory. Benefit versus no greater benefit group means were also provided for only those studies providing urinary biomarker verification of protein intakes (Table2).

Spreads in protein consumption between higher and lower protein groups in protein spread analysis. Spread RDA – Benefit = only those studies meeting RDA inclusion criteria in which the higher protein group experienced greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention; Spread All – Benefit = all studies in which the higher protein group experienced greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention; Spread RDA –No > Benefit = only those studies meeting RDA inclusion criteria in which the higher protein group experienced no greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention; Spread All – No > Benefit = all studies in which the higher protein group experienced greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention.

Protein change theory

Not all weight loss only studies reported baseline dietary intake. In those 25 that did, the average percent increase in habitual g/kg/day protein intake was 28.6% in 17 studies which showed anthropometric benefit to a higher protein intake compared to only 4.9% in eight studies that showed no additional benefit (Tables3 &4).

Since perhaps some scientists would find excluding studies with a sub-RDA lower protein group a more balanced analysis of protein change theory, a reanalysis was performed including only the 13 baseline intake reporting studies that met RDA inclusion criteria. The 13 were divided into: 1) those seven showing additional benefit to increased protein and 2) those six that did not (Figure3). This additional analysis supported protein change theory as the mean spread in g/kg/day protein intake in the seven studies showing a benefit of increased protein was 36.9%. This was relatively close to the 28.6% figure from the original analysis (Table2). Similarly, the mean spread in the six studies showing no benefit of increased protein was −0.1%. This was close to the 4.9% figure from the original analysis and supported protein change theory. Benefit versus no greater benefit group means were also provided for only those studies providing urinary biomarker verification of protein intakes (Tables3 &4).

Percent deviation from habitual protein intake among groups in protein change analysis. Only weight loss studies reporting baseline protein intake. Change RDA – Benefit = only those studies meeting RDA inclusion criteria in which the higher protein group experienced greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention; Change All – Benefit = all studies in which the higher protein group experienced greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention; Change RDA –No > Benefit = only those studies meeting RDA inclusion criteria in which the higher protein group experienced no greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention; Change – No > Benefit = all studies in which the higher protein group experienced greater anthropometric benefits than controls during the intervention.

Discussion

This review supports our protein spread and change theories as possible explanations for discrepancies in the protein and weight management literature. Among studies showing greater anthropometric benefits of higher protein there is typically a relatively large% difference spread of approximately 58.4% between the g/kg/day intake of the higher protein group and control. Additionally, that the higher protein group’s during study g/kg/day protein intake is substantially different, or approximately 28.6% greater than baseline, is important. When these spreads and habitual deviations are lower, closer to 38.8% and 4.9% respectively, there is little additional anthropometric benefit produced by higher protein interventions. Evidence weighs heavily toward studies showing anthropometric benefits of increased protein intake[2, 11–44]. Those that did not support additional benefits still showed that higher protein was equally as good as an alternative diet[45–60].

Protein spread theory

Studies showing anthropometric benefits in the protein spread analysis had a higher protein group consuming on average 58.4% g/kg/day more protein than controls. For example, Leidy et al. had overweight and obese women maintain a caloric deficit of ~750 kcal/day for 12 wk. Controls consumed 0.82 g/kg protein/day. Higher protein participants consumed 1.41 g/kg/day. The higher protein group retained significantly more lean mass (+1.3 kg) than control, and achieved the same weight loss[31]. In another study, participants consuming 1.71 g/kg/day protein gained back 1 kg less weight, lost 2.2 kg more fat, and gained 1.2 kg more fat-free mass versus controls consuming 1.29 g/kg/day protein during 13 wk weight maintenance[44]. Similarly, during 26–52 wk weight maintenance, 3.1-3.6 and 2–3.3 kg greater weight and fat loss were achieved versus control when higher protein groups achieved protein intake spreads from controls of 45.9-68.5%[2, 16].

There appeared to be some outliers within studies showing no additional benefit of a higher protein intake (Table2), however, there appeared to be plausible explanations for nearly all outliers. Wycherley et al.[60] was grouped in the “no benefit” studies, despite showing a 2 kg greater reduction in fat mass in higher protein participants achieving a 67.7% g/kg/day spread because this fat reduction just missed statistical significance (p = 0.06). There were also similar trends for body mass and waist circumference[60]. A six wk study by Johnston et al. did not show a superior anthropometric effect of a 98.8% g/kg/day spread[51], but did not assess baseline intake and used a bioelectrical impedance device to assess body composition, shown to be problematic in short weight loss[72]. Higher protein participants did have greater diet satisfaction and less hunger[72] which influences long-term dietary success[25, 29]. Although there were no greater anthropometric benefits of a 71.6% g/kg/day spread in a 12 wk study by Luscombe et al., the lower protein group contained double the # of women in the higher protein group. Meanwhile the higher protein group has more than double the urinary albumin level of lower protein participants at baseline, seeming to indicate some discrepancy between groups in protein metabolism[53]. Although there did not appear a plausible explanation why a 69.9% g/kg/day intake spread did not yield greater anthropometric benefits in a another study by Luscombe and colleagues[54] as in the previous outliers[51, 53] no baseline dietary information was provided and thus it is unknown if these large between group spreads actually involved any appreciable change in habitual protein intake for the higher protein groups.

A flaw in some long duration trials was that while no differences in weight loss were shown with higher protein, body composition was not assessed. Additionally, protein intake spread between groups was often less than designed[45, 46, 48, 57, 61], a problem noted in a recent editorial[62].

Protein change theory

Multiple studies in this review (Table3) showed 0.8-3.3 g/kg/day greater fat loss in higher protein participants over 4–26 wk when change from habitual intake was 20.2%-35.3%[11, 32, 38, 43]. There appeared to be three outliers in Table3[22, 33, 35]. Higher protein participants in these studies achieved changes in habitual protein intake of only 5.4, -6.4, and 6.9% respectively yet still saw greater anthropometric improvements compared to controls. However, these studies involved appreciable g/kg/day protein intake spreads of 32.2, 39.7, and 47.9% respectively. Perhaps this spread, coupled with the fact that the lower protein groups in Mahon et al. and McMillan Price et al. reduced their habitual protein intakes the most of any studies in this review, -36.4 and −36.5% respectively, was a combination that allowed for superior anthropometric outcomes for these higher protein participants. Although not as pronounced, lower protein participants in the Frestedt et al. study notably decreased their habitual protein intake by −22.4%, leading to the lowest during study lower protein group intake in this review of 0.59 g/kg. Perhaps this coupled with the aforementioned spread was enough to allow for anthropometric differences between protein groups. Additionally in regard to the McMillan-Price et al. study[35], participants were stratified: 1) lower protein/higher GI; 2) lower protein/lower GI; 3) higher protein/higher GI; and 4) higher protein/lower GI[35]. In women, higher protein/higher GI lost significantly more body and fat mass than lower protein/higher GI. There was a 47.9% g/kg/day protein intake spread between these groups. There was also a small 6.74% increase in habitual protein intake for the higher protein/higher GI group. Conversely, higher protein/lower GI was less effective for weight and fat loss compared to lower protein/lower GI. Results were puzzling as lower GI can aid weight management. However, spread in protein intake between low GI groups was only 32.8% and higher protein/lower GI did not change their habitual intake (± 0%). Thus, three of the four theory related means nearly fit our mean theory numbers, with all four fitting directionally. Some have shown gender difference in response to higher protein[20, 42] while others have not[23, 44].

In table4 there appeared to be two outliers within studies showing no additional benefit of a higher protein intake, however, there appeared to be plausible explanations for both. Higher protein participants in a study by Rizkalla et al. increased their habitual protein intake by 31% and achieved a greater reduction in waist circumference (p = 0.07), trunk fat (p = 0.08), total fat (p = 0.10), body-weight (p = 0.14), and adipocyte diameter (p = 0.048). This study[56] was grouped in the “no benefit” studies because only the adipocyte diameter finding was statistically significant and per the methods of this review, only whole/regional body anthropometric measures could be considered “anthropometric benefits.” The higher protein group in a study by Magrans-Courtney et al. showed no greater benefit of a 32% increase in habitual protein intake. However, the increase in habitual protein intake in this higher protein group of 32% was a composite of a 55% increase at wk 10 and a 10% increase at wk 14[55]. The reported protein intake at wk 10 had a standard deviation of ± 47 g as compared to ± 10–13 g at wk 0 and 14. Thus, the increase in habitual intake was likely closer to 10%, more in line with the 4.9% average from this group of studies (Table4).

A flaw in previous trials was that at times higher protein groups consumed more protein than control, yet less than their habitual intake, and saw no difference in anthropometrics[33, 52, 57, 61]. Thus, the “intervention” diet was really not an intervention to their metabolism. The human body does not know persay the% kcals it is receiving from each macronutrient. In some cases, increasing the% of kcals from protein during energy restriction can actually result in less protein being consumed during intervention than habitual intake as a simple function of energy deficit. Habitual intake mediates the effects of protein on bone health and satiety[73, 74] and studies have shown that that the thermic effect of protein decreases over time while dieting[53, 54]. We propose that changes in habitual protein intake may mediate the effects of protein on lean body mass[70]. Perhaps a progressive loss of body and lean body mass with dieting increases the capacity for amino acid deposition. Meanwhile this more rapid disposal of amino acids from circulation may mandate a progressive increase in protein intake to achieve satiety[74] and ultimately weight management goals.

The lack of accounting for protein distribution throughout the day may also explain outliers in this review. Two leading protein metabolism research groups have recently discussed the importance of spacing protein evenly throughout the day to optimize body composition endpoints[75, 76]. Thus, it is unlikely that adding additional protein to meals that were already protein rich has the same effect as achieving a higher daily protein intake by adding protein to meals that were previously protein poor.

New approaches in data reporting and assessment

Recently, Layman et al. and Flechtner-Mors et al. reported body composition changes as a ratio of fat lost/lean mass lost[21, 27]. Westerterp-Plantenga et al. generated an energy efficiency ratio of body mass regain/energy intake[44], while Ballesteros-Pamar et al. examined the ratio of weight loss achieved/energy deficit[45]. Layman et al. and Flechtner-Mors et al. analyzed participants achieving at least 10% weight loss and found a greater prevalence of higher protein participants[21, 29], while Frestedt et al. split participants into “responders” and “non-responders”[22]. If all studies reported these additional data sets and baseline dietary intakes, further insight could be gained. Although most studies in this review verified protein intakes with urinary biomarkers (Tables2,3,4), the lack of these assessments in all studies is a limitation. These measures should be assessed whenever possible as long term adherence to a weight loss diet is typically poor[77] and dietary recalls are prone to underreporting, although to a lesser extent than FFQs[78]. Additionally, the varied study durations, gender, age groups, protein types, and body composition assessments in this review are limitations, however, general conclusions can be drawn from the consistency in study findings per our theories.

Conclusions

Most adults habitually consume 88 g or ~1.07 g/kg/day protein[6, 79]. Per protein change theory, a 28.6% increase to a representative habitual protein intake would involve an increase of about 25–30 g/day or from 1.07 g/kg/day to 1.38 g/kg/day, which approximates the protein intake of most high protein groups in this review. Baseline protein intake should be known prior to deciding the level of protein intervention during a trial.

Designing studies with sufficient spread between group protein intakes would more likely assure a considerable difference between groups is achieved during the trial even with an expected degree of dietary non-compliance. Protein prescription proportional to bodyweight should become the norm in future studies versus% energy as should control for even distribution of protein across meals[75]. Finally, there is need for further examination of our theories in the context of change from higher baseline protein intakes.

Higher protein interventions were deemed successful when there was, on average, a 58.4% g/kg/day between group intake spread. In this review, the average change in habitual protein intake in weight loss studies showing higher protein to be more effective than control was +28.6%. These findings support our protein spread and change theories. Further research is needed to determine if there are specific spread and change thresholds.

Authors’ information

JDB holds an MS in Sports Dietetics, a BS in Exercise Science and is a Registered Dietitian and Senior Scientist for USANA Health Sciences, Inc. JDB is an Adjunct Professor to graduate students in the Division of Nutrition at the University of Utah. JDB has worked in the field with weight management clientele, collegiate, and professional athletes and in the lab researching shoulder biomechanics and the role of macronutrients in hypertension. Having reviewed protein metabolism literature, JDB’s current objective is to provide insight on scientific research based upon phenomena observed by practitioners in the field. BMD holds a PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology from Oregon State University and has published numerous original scientific studies, most recently on the role of vitamin D in active populations. As Executive Director of Product & Technology Innovation, BMD oversees an expansive clinical studies program involving collaborations between USANA Health Sciences and several universities and private research institutions.

Funding

JDB and BMD are employees of USANA Health Sciences, Inc. This review was prepared on company time.

Abbreviations

- RDA:

-

Recommended dietary allowance

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- FFQs:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- GI:

-

Glycemic index

- g/kg/day:

-

grams protein per kilogram per day.

References

Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W: Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009, 28: w822-w831. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822.

Skov AR, Toubro S, Ronn B, Holm L, Astrup A: Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999, 23: 528-536. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800867.

Krieger JW, Sitren HS, Daniels MJ, Langkamp-Henken B: Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression 1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 83: 260-274.

Abete I, Astrup A, Martinez JA, Thorsdottir I, Zulet MA: Obesity and the metabolic syndrome: role of different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and maintenance. Nutr Rev. 2010, 68: 214-231. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00280.x.

Schoeller DA, Buchholz AC: Energetics of obesity and weight control: does diet composition matter?. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105: S24-S28.

Austin GL, Ogden LG, Hill JO: Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011, 93: 836-843. 10.3945/ajcn.110.000141.

Champagne CM, Broyles ST, Moran LD, Cash KC, Levy EJ, Lin PH: Dietary intakes associated with successful weight loss and maintenance during the Weight Loss Maintenance trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011, 111: 1826-1835. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.014.

World Health Organization: Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition: report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation. WHO technical report series. 2007, 935: 1-265.

Layman DK: Protein quantity and quality at levels above the RDA improves adult weight loss. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004, 23: 631S-636S.

Campbell WW, Trappe TA, Wolfe RR, Evans WJ: The recommended dietary allowance for protein may not be adequate for older people to maintain skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001, 56: M373-M380. 10.1093/gerona/56.6.M373.

Mojtahedi MC, Thorpe MP, Karampinos DC, Johnson CL, Layman DK, Georgiadis JG: The effects of a higher protein intake during energy restriction on changes in body composition and physical function in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011, 66: 1218-1225.

Abete I, Parra D, Martinez JA: Legume-, fish-, or high-protein-based hypocaloric diets: effects on weight loss and mitochondrial oxidation in obese men. J Med Food. 2009, 12: 100-108. 10.1089/jmf.2007.0700.

Aldrich ND, Reicks MM, Sibley SD, Redmon JB, Thomas W, Raatz SK: Varying protein source and quantity do not significantly improve weight loss, fat loss, or satiety in reduced energy diets among midlife adults. Nutr Res. 2011, 31: 104-112. 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.01.004.

Baer DJ, Stote KS, Paul DR, Harris GK, Rumpler WV, Clevidence BA: Whey protein but not soy protein supplementation alters body weight and composition in free-living overweight and obese adults. J Nutr. 2011, 141: 1489-1494. 10.3945/jn.111.139840.

Claessens M, van Baak MA, Monsheimer S, Saris WH: The effect of a low-fat, high-protein or high-carbohydrate ad libitum diet on weight loss maintenance and metabolic risk factors. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009, 33: 296-304. 10.1038/ijo.2008.278.

Clifton PM, Keogh JB, Noakes M: Long-term effects of a high-protein weight-loss diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 87: 23-29.

Demling RH, DeSanti L: Effect of a hypocaloric diet, increased protein intake and resistance training on lean mass gains and fat mass loss in overweight police officers. Ann Nutr Metab. 2000, 44: 21-29. 10.1159/000012817.

Due A, Toubro S, Skov AR, Astrup A: Effect of normal-fat diets, either medium or high in protein, on body weight in overweight subjects: a randomised 1-year trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 1283-1290. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802767.

Evans EM, Mojtahedi MC, Thorpe MP, Valentine RJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Layman DK: Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: a randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012, 9: 55-10.1186/1743-7075-9-55.

Farnsworth E, Luscombe ND, Noakes M, Wittert G, Argyiou E, Clifton PM: Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 78: 31-39.

Flechtner-Mors M, Boehm BO, Wittmann R, Thoma U, Ditschuneit HH: Enhanced weight loss with protein-enriched meal replacements in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010, 26: 393-405. 10.1002/dmrr.1097.

Frestedt JL, Zenk JL, Kuskowski MA, Ward LS, Bastian ED: A whey-protein supplement increases fat loss and spares lean muscle in obese subjects: a randomized human clinical study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008, 5 (8): 8-

Hursel R, Westerterp-Plantenga MS: Green tea catechin plus caffeine supplementation to a high-protein diet has no additional effect on body weight maintenance after weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89: 822-830. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27043.

Josse AR, Atkinson SA, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM: Increased consumption of dairy foods and protein during diet- and exercise-induced weight loss promotes fat mass loss and lean mass gain in overweight and obese premenopausal women. J Nutr. 2011, 141: 1626-1634. 10.3945/jn.111.141028.

Larsen TM, Dalskov SM, Van BM, Jebb SA, Papadaki A, Pfeiffer AF: Diets with high or low protein content and glycemic index for weight-loss maintenance. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 2102-2113. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007137.

Lasker DA, Evans EM, Layman DK: Moderate carbohydrate, moderate protein weight loss diet reduces cardiovascular disease risk compared to high carbohydrate, low protein diet in obese adults: A randomized clinical trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008, 5 (30): 30-

Layman DK, Boileau RA, Erickson DJ, Painter JE, Shiue H, Sather C: A reduced ratio of dietary carbohydrate to protein improves body composition and blood lipid profiles during weight loss in adult women. J Nutr. 2003, 133: 411-417.

Layman DK, Evans E, Baum JI, Seyler J, Erickson DJ, Boileau RA: Dietary protein and exercise have additive effects on body composition during weight loss in adult women. J Nutr. 2005, 135: 1903-1910.

Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D: A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults. J Nutr. 2009, 139: 514-521. 10.3945/jn.108.099440.

Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS: Additional protein intake limits weight regain after weight loss in humans. Br J Nutr. 2005, 93: 281-289. 10.1079/BJN20041305.

Leidy HJ, Carnell NS, Mattes RD, Campbell WW: Higher protein intake preserves lean mass and satiety with weight loss in pre-obese and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007, 15: 421-429. 10.1038/oby.2007.531.

Lockwood CM, Moon JR, Tobkin SE, Walter AA, Smith AE, Dalbo VJ: Minimal nutrition intervention with high-protein/low-carbohydrate and low-fat, nutrient-dense food supplement improves body composition and exercise benefits in overweight adults: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008, 5: 11-10.1186/1743-7075-5-11.

Mahon AK, Flynn MG, Stewart LK, McFarlin BK, Iglay HB, Mattes RD: Protein intake during energy restriction: effects on body composition and markers of metabolic and cardiovascular health in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007, 26: 182-189.

McAuley KA, Hopkins CM, Smith KJ, McLay RT, Williams SM, Taylor RW: Comparison of high-fat and high-protein diets with a high-carbohydrate diet in insulin-resistant obese women. Diabetologia. 2005, 48: 8-16. 10.1007/s00125-004-1603-4.

McMillan-Price J, Petocz P, Atkinson F, O'neill K, Samman S, Steinbeck K: Comparison of 4 diets of varying glycemic load on weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in overweight and obese young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166: 1466-1475. 10.1001/archinte.166.14.1466.

Meckling KA, Sherfey R: A randomized trial of a hypocaloric high-protein diet, with and without exercise, on weight loss, fitness, and markers of the Metabolic Syndrome in overweight and obese women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007, 32: 743-752. 10.1139/H07-059.

Morenga LT, Williams S, Brown R, Mann J: Effect of a relatively high-protein, high-fiber diet on body composition and metabolic risk factors in overweight women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64: 1323-1331. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.163.

Navas-Carretero S, Abete I, Zulet MA, Martinez JA: Chronologically scheduled snacking with high-protein products within the habitual diet in type-2 diabetes patients leads to a fat mass loss: a longitudinal study. Nutr J. 2011, 10 (74): 74-

Nickols-Richardson SM, Coleman MD, Volpe JJ, Hosig KW: Perceived hunger is lower and weight loss is greater in overweight premenopausal women consuming a low-carbohydrate/high-protein vs high-carbohydrate/low-fat diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105: 1433-1437. 10.1016/j.jada.2005.06.025.

Noakes M, Keogh JB, Foster PR, Clifton PM: Effect of an energy restricted, high protein, low fat diet relative to a conventional high carbohydrate, low fat diet on weight loss, body composition, nutritional status, and markers of cardiovascular health in obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81: 1298-1306.

Papakonstantinou E, Triantafillidou D, Panagiotakos DB, Koutsovasilis A, Saliaris M, Manolis A: A high-protein low-fat diet is more effective in improving blood pressure and triglycerides in calorie-restricted obese individuals with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64: 595-602. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.29.

Parker B, Noakes M, Luscombe N, Clifton P: Effect of a high-protein, high-monounsaturated fat weight loss diet on glycemic control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 425-430. 10.2337/diacare.25.3.425.

Te Morenga LA, Levers MT, Williams SM, Brown RC, Mann J: Comparison of high protein and high fiber weight-loss diets in women with risk factors for the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. Nutr J. 2011, 10 (40): 40-

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lejeune MP, Nijs I, Van OM, Kovacs EM: High protein intake sustains weight maintenance after body weight loss in humans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 57-64. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802461.

Ballesteros-Pomar MD, Calleja-Fernandez AR, Vidal-Casariego A, Urioste-Fondo AM, Cano-Rodriguez I: Effectiveness of energy-restricted diets with different protein:carbohydrate ratios: the relationship to insulin sensitivity. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13: 2119-2126. 10.1017/S1368980009991881.

Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Keogh JB, Luscombe ND, Wittert GA, Clifton PM: Long-term effects of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on weight control and cardiovascular risk markers in obese hyperinsulinemic subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 661-670. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802617.

Delbridge EA, Prendergast LA, Pritchard JE, Proietto J: One-year weight maintenance after significant weight loss in healthy overweight and obese subjects: does diet composition matter?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 90: 1203-1214. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27209.

de Souza RJ, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Hall KD, LeBoff MS, Loria CM: Effects of 4 weight-loss diets differing in fat, protein, and carbohydrate on fat mass, lean mass, visceral adipose tissue, and hepatic fat: results from the POUNDS LOST trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95: 614-625. 10.3945/ajcn.111.026328.

Gilbert JA, Joanisse DR, Chaput JP, Miegueu P, Cianflone K, Almeras N: Milk supplementation facilitates appetite control in obese women during weight loss: a randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2011, 105: 133-143. 10.1017/S0007114510003119.

Hinton PS, Rector RS, Donnelly JE, Smith BK, Bailey B: Total body bone mineral content and density during weight loss and maintenance on a low- or recommended-dairy weight-maintenance diet in obese men and women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64: 392-399. 10.1038/ejcn.2009.156.

Johnston CS, Tjonn SL, Swan PD: High-protein, low-fat diets are effective for weight loss and favorably alter biomarkers in healthy adults. J Nutr. 2004, 134: 586-591.

Larsen RN, Mann NJ, Maclean E, Shaw JE: The effect of high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a 12 month randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2011, 54: 731-740. 10.1007/s00125-010-2027-y.

Luscombe ND, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Parker B, Wittert G: Effects of energy-restricted diets containing increased protein on weight loss, resting energy expenditure, and the thermic effect of feeding in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 652-657. 10.2337/diacare.25.4.652.

Luscombe ND, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Farnsworth E, Wittert G: Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on weight loss and energy expenditure after weight stabilization in hyperinsulinemic subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 27: 582-590. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802270.

Magrans C, Wilborn C, Rasmussen C, Ferreira M, Greenwood L, Campbell B: Effects of diet type and supplementation of glucosamine, chondroitin, and MSM on body composition, functional status, and markers of health in women with knee osteoarthritis initiating a resistance-based exercise and weight loss program. J Int Soc Sports Nutr . 2011, 20 (8): 8-

Rizkalla SW, Prifti E, Cotillard A, Pelloux V, Rouault C, Allouche R: Differential effects of macronutrient content in 2 energy-restricted diets on cardiovascular risk factors and adipose tissue cell size in moderately obese individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95: 49-63. 10.3945/ajcn.111.017277.

Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Smith SR, Ryan DH, Anton SD: Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 859-873. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748.

Sargrad KR, Homko C, Mozzoli M, Boden G: Effect of high protein vs high carbohydrate intake on insulin sensitivity, body weight, hemoglobin A1c, and blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105: 573-580. 10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.009.

Sukumar D, Ambia-Sobhan H, Zurfluh R, Schlussel Y, Stahl TJ, Gordon CL: Areal and volumetric bone mineral density and geometry at two levels of protein intake during caloric restriction: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2011, 26: 1339-1348. 10.1002/jbmr.318.

Wycherley TP, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Cleanthous X, Keogh JB, Brinkworth GD: A high-protein diet with resistance exercise training improves weight loss and body composition in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010, 33: 969-976. 10.2337/dc09-1974.

Frisch S, Zittermann A, Berthold HK, Gotting C, Kuhn J, Kleesiek K: A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of carbohydrate-reduced or fat-reduced diets in patients attending a telemedically guided weight loss program. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009, 8 (36): 36-

Astrup A, Pedersen SD: Is a protein calorie better for weight control?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95: 535-536. 10.3945/ajcn.111.031625.

Sukhatme PV, Margen S: Models for protein deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978, 31: 1237-1256.

Millward DJ: An adaptive metabolic demand model for protein and amino acid requirements. Br J Nutr. 2003, 90: 249-260. 10.1079/BJN2003924.

Hegsted DM: From chick nutrition to nutrition policy. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000, 20: 1-19. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.1. 1–19

Price GM, Halliday D, Pacy PJ, Quevedo MR, Millward DJ: Nitrogen homeostasis in man: influence of protein intake on the amplitude of diurnal cycling of body nitrogen. Clin Sci (Lond). 1994, 86: 91-102.

Pacy PJ, Price GM, Halliday D, Quevedo MR, Millward DJ: Nitrogen homeostasis in man: the diurnal responses of protein synthesis and degradation and amino acid oxidation to diets with increasing protein intakes. Clin Sci (Lond). 1994, 86: 103-116.

Soenen S, Westerterp-Plantenga MS: Changes in body fat percentage during body weight stable conditions of increased daily protein intake vs. control. Physiol Behav. 2010, 101: 635-638. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.09.014.

Bray GA, Smith SR, De JL, Xie H, Rood J, Martin CK: Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012, 307: 47-55. 10.1001/jama.2011.1918.

Petzke KJ, Lemke S, Klaus S: Increased fat-free body mass and no adverse effects on blood lipid concentrations 4 weeks after additional meat consumption in comparison with an exclusion of meat in the diet of young healthy women. J Nutr Metab. 2011, 2011: 210930-Epub;%2011 Jun 14.: 210930

Marr JW, Heady JA: Within- and between-person variation in dietary surveys: number of days needed to classify individuals. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1986, 40: 347-364.

Vazquez JA, Janosky JE: Validity of bioelectrical-impedance analysis in measuring changes in lean body mass during weight reduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991, 54: 970-975.

Sebastian A: Protein consumption as an important predictor of lower-limb bone mass in elderly women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 82: 1355-1356.

Long SJ, Jeffcoat AR, Millward DJ: Effect of habitual dietary-protein intake on appetite and satiety. Appetite. 2000, 35: 79-88. 10.1006/appe.2000.0332.

Layman DK: Dietary Guidelines should reflect new understandings about adult protein needs. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2009, 6 (12): 12-

Paddon-Jones D, Rasmussen BB: Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009, 12: 86-90. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831cef8b.

Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ: Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005, 293: 43-53. 10.1001/jama.293.1.43.

Subar AF, Kipnis V, Troiano RP, Midthune D, Schoeller DA, Bingham S: Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: the OPEN study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 158: 1-13. 10.1093/aje/kwg092.

McDowell MA, Fryar CD, Ogden CL, Flegal KM: Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2003–2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2008, 10: 1-45.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Micah Drummond for his critical third party review of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JDB and BMD are employees of USANA Health Sciences, Inc. USANA Health Sciences, Inc. had no role in the direction, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this review. USANA Health Sciences has provided for the article processing charge. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions

JDB designed the manuscript, collected and analyzed study data, wrote, and edited the manuscript. BMD provided manuscript direction and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bosse, J.D., Dixon, B.M. Dietary protein in weight management: a review proposing protein spread and change theories. Nutr Metab (Lond) 9, 81 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-81

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-81