Abstract

Limited data on sex differences in body composition changes in response to higher protein diets (PRO) compared to higher carbohydrate diets (CARB) suggest that a PRO diet helps preserve lean mass (LM) in women more so than in men.

Objective

To compare male and female body composition responses to weight loss diets differing in macronutrient content.

Design

Twelve month randomized clinical trial with 4mo of weight loss and 8mo weight maintenance.

Subjects

Overweight (N = 130; 58 male (M), 72 female (F); BMI = 32.5 ± 0.5 kg/m2) middle-aged subjects were randomized to energy-restricted (deficit ~500 kcal/d) diets providing protein at 1.6 g.kg-1.d-1 (PRO) or 0.8 g.kg-1.d-1 (CARB). LM and fat mass (FM) were measured using dual X-ray absorptiometry. Body composition outcomes were tested in a repeated measures ANOVA controlling for sex, diet, time and their two- and three-way interactions at 0, 4, 8 and 12mo.

Results

When expressed as percent change from baseline, males and females lost similar amounts of weight at 12mo (M:-11.2 ± 7.1 %, F:-9.9 ± 6.0 %), as did diet groups (PRO:-10.7 ± 6.8 %, CARB:-10.1 ± 6.2 %), with no interaction of gender and diet. A similar pattern emerged for fat mass and lean mass, however percent body fat was significantly influenced by both gender (M:-18.0 ± 12.8 %, F:-7.3 ± 8.1 %, p < 0.05) and diet (PRO:-14.3 ± 11.8 %, CARB:-9.3 ± 11.1 %, p < 0.05), with no gender-diet interaction. Compared to women, men carried an extra 7.0 ± 0.9 % of their total body fat in the trunk (P < 0.01) at baseline, and reduced trunk fat during weight loss more than women (M:-3.0 ± 0.5 %, F:-1.8 ± 0.3 %, p < 0.05). Conversely, women carried 7.2 ± 0.9 % more total body fat in the legs, but loss of total body fat in legs was similar in men and women.

Conclusion

PRO was more effective in reducing percent body fat vs. CARB over 12mo weight loss and maintenance. Men lost percent total body fat and trunk fat more effectively than women. No interactive effects of protein intake and gender are evident.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight and obesity as a public health issue is well established in adult men and women; however, the distribution and storage of adipose tissue as well as the metabolic consequences of elevated levels of adiposity appear to be impacted by sex status. It is well established that females store greater amounts of adipose tissue compared to males, whether expressed as absolute amounts or in relation to body weight (i.e. percent body fat or %Fat) [1]. Furthermore, with regard to fat depot distribution, there is a dimorphic patterning characterized by the typical woman storing greater amounts in the lower body, particularly the gluteofemoral region, and the typical man having the abdomen as the favored depot [1]. Because of the influence of sex hormones on this depot, the majority of females assume a more androidal fat pattern after the menopausal transition [2]. With regard to central adiposity, comparing subcutaneous and visceral depots, women are more likely to have a larger subcutaneous depot whereas men store more visceral adipose tissue [3, 4], although again, this preferential depot may be altered with reductions in estrogen with the postmenopausal transition [2].

It is well established that weight loss in overweight or obese individuals reduces risk for metabolic diseases associated with adiposity [5]. However, body composition changes that occur with weight loss typically include loss of both fat mass (FM) and lean mass (LM). For example, a weight loss of 10 % body mass with dietary energy restriction decreased both FM and skeletal muscle in obese women [6]. Research, although limited, suggests that there are sex differences in body composition changes resulting from weight loss. Men appear to lose both FM and LM at a similar rate, whereas women have been found to lose more FM than LM, with these changes being related to baseline body composition [7, 8]. Furthermore, regionally, it appears that although both men and women lose FM from the abdominal area and the femoral region, men may lose more abdominal fat, and women may lose more femoral FM [7, 9].

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute guidelines call for weight loss regimens that attenuate loss of LM while losing FM [5]. The most effective macronutrient composition of the diet for optimal body composition change during weight loss is currently a high priority research area [10] and may have implications for optimal body composition changes, especially in mid-life and older adults [11]. Our own research suggests that weight loss diets higher in protein and lower in carbohydrate (PRO) appear to promote marginally more weight loss, similarly to previous findings [12, 13], but augment FM loss with a relative preservation of LM compared to a conventional higher carbohydrate/lower protein diet (CARB) [14] although not all studies are in agreement [15, 16].

The dietary protein requirement is frequently expressed as 15-20 % of total energy [17]. This format may be inappropriate when energy intake is determined without respect to the absolute protein requirement. For example, 15 % energy from protein may fall short of the absolute protein requirement of 0.8 g·kg-1·d-1 during energy restriction, as in a weight loss diet. Theoretically, individuals with more LM, including males relative to females, may be particularly susceptible to suboptimal protein intakes during energy restriction, promoting a loss of lean body mass [17]. However, one study on body composition changes in response to PRO compared to CARB weight loss diets suggest that a PRO diet helps preserve LM in women more so than in men [9]. Insufficient data directly comparing male and female body composition responses to weight loss diets differing in macronutrient content are currently available to draw conclusions or develop dietary recommendations.

In this context, the purpose of this analysis was to examine sex differences in whole body and regional body composition changes, including FM and LM, resulting from weight loss in response to isocaloric PRO and CARB weight loss diets. We anticipated that the PRO diet would more favorably affect changes in body composition (i.e. promote FM loss and attenuate LM loss) in men, who have greater LM and may thus require more protein, than in women, compared to the CARB diet.

Subjects and methods

Overview

This study was a 12 mo two-center weight loss trial (4 mo active weight loss; 8 mo weight maintenance) using a parallel-arm randomized design. This gender comparison is a secondary analysis of the weight loss trial previously reported elsewhere [18, 19]. Subjects were blocked by body mass index (BMI), sex and age then randomized into diets prescribing either a low carbohydrate to protein ratio (PRO group: ~ 1.6 g·kg-1·d-1 of protein or 30 % of energy from protein, 40 % carbohydrate and 30 % fat) or a high carbohydrate to protein ratio (CARB group: 0.8 g·kg-1·d-1 of protein or 15 % protein, 55 % carbohydrate and 30 % fat). Due to study design of the diet treatment, it was not possible to blind subjects and research staff to group assignment. (See Diet Treatments below.)

Subjects

One hundred thirty men (n =58) and women (n =72) aged 40 to 56 y were recruited to participate in the weight loss study. Exclusion criteria were BMI < 26 kg/m2, body weight > 140 kg (due to DXA scanning bed constraints), smoking, any existing medical conditions requiring medications that impact primary or secondary outcomes of the study, i.e. use of oral steroids or use of anti-depression medication. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and The Pennsylvania State University. Subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

All subjects participated in a baseline evaluation period that included a 24-h food recall, instructions for weighing and recording of foods, two 3-d weighed food records during separate weeks and measurements of height and weight. This evaluation period was 10 to 20 d and served as an initial control period for each subject. During the baseline period, subjects were instructed to maintain stable body weight and to consume a diet similar to the past 6 mo. After the baseline period, subjects reported to the laboratory after a 12 h overnight fast for measurements of body weight and body composition.

Diet treatments

The PRO diet prescribed dietary protein at 1.6 g. kg -1.d-1 (~30 % of energy intake) with a carbohydrate/protein ratio <1.5 and dietary lipids ~30 % energy intake. The CARB diet provided dietary protein equal to 0.8 g.kg-1.d-1 (~15 % of energy intake) with a carbohydrate/protein ratio > 3.5 and total fat ~ 30 % of energy intake. These diets were designed to fall within the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range of the DRIs as established by the Institute of Medicine [20] with minimum RDA intakes for carbohydrates >130 g/d and protein >0.8 g.kg-1.d-1 and with upper ranges for carbohydrates <65 % and protein <35 % of total energy intake. The two diets were formulated to be equal in energy (7.10 MJ d-1, 1700 kcal d-1 for females; 7.94 MJ d-1, 1900 kcal d-1 for males), total fat intake (30 % of energy) and fiber (17 g/1000 kcal). Each diet group received a menu plan with meals for each day meeting established nutritional requirements [20] and dietary fat guidelines [21]. Diet differences between groups were designed to reflect direct substitution of foods in the protein groups (meats, dairy, eggs and nuts) for foods with high carbohydrate content (breads, rice, cereals, pasta and potatoes). The education guidelines for the CARB group followed the USDA Food Guide Pyramid [22] and emphasized restricting dietary fat and cholesterol with use of whole grain breads, rice, cereals and pasta. For the PRO group, the education guidelines emphasized use of high quality low fat proteins including lean meat, reduced fat dairy and eggs or egg substitutes. Both diets included 5 vegetable servings/d and 2 to 3 fruit servings/d.

Education Program and Monitoring

Subjects were provided electronic food scales and instructed to weigh all food servings at all meals. Subjects were required to report two 3-d weighed food records during the baseline period prior to assignment to diet groups. Nutrient intakes were evaluated as mean daily intakes from the 3-d weighed records using Nutritionist Pro software (First DataBank Inc. 2003, San Bruno, CA). After baseline data collection, subjects received specific diet program instructions from a research dietitian including the menus, food substitutions and portion sizes. Throughout the 12-mo study, subjects were required to attend a 1 h meeting each week at the weight management research facility. Meetings were specific for each treatment group and directed by research dietitians who provided diet and exercise information, answered questions and reviewed diet records for treatment compliance. Each week, subjects were weighed in light clothing without shoes and turned in 3-d weighed food records.

The education program focused on diet compliance with some exercise guidance. Activity guidelines emphasized physical activity lifestyle recommendations based on the NIH Guidelines for Weight Management [5]. These guidelines recommend a minimum of 30 min of walking 5 d/wk. Participation in physical activity for the groups was voluntary. Physical activity was monitored using daily activity logs and armband accelerometers (BodyMedia, Cincinnati, OH) worn 3 d/mo. Activity logs were collected each week. Based on these measurements, subjects averaged less than 100 min/wk of added exercise. These results were similar between diet treatment groups.

Body composition

After 4, 8 and 12 mo, subjects reported to the laboratory after a 12 h overnight fast for measurements of body weight and body composition. Body weight was measured using an electronic scale (Tanita, Model BWB-627A, Tokyo Japan). Height was measured using a stadiometer. Body composition was determined by dual energy X-ray absorptometry (DXA; Illinois: Hologic QDR 4500A, software version 11.1:3; Penn State: Hologic QDR 4500 W, software version 12.5) and scans for a given individual were analyzed by the same technician. A regional analysis was performed per manufacturer guidelines, which involved placing lines bisecting the femoral neck and the glenohumeral joint. Appendicular lean mass was determined by summing lean soft tissue mass from leg and arm subregions. The appendicular skeletal muscle index was calculated as total appendicular lean mass / height² in meters.

Data Analyses and Statistics

Data were screened for normality and outliers. Change in dietary intakes and body composition were compared across time, with respect to diets and sex using unstructured repeated measures ANOVA models. Models were applied to intakes of total energy, protein, carbohydrate and fat, as well as weight and weight loss from baseline, total body LM, FM and %Fat and regional %Fat of the legs and trunk. The ratio of FM of the trunk vs. the legs was also modeled, as well as the distribution of fat mass of the legs and trunk, that is, the proportion of total body FM contained in these regions. These parameters permitted contrasting of the primary site of weight loss across diets and sexes. All models used intent-to-treat analysis and tested for all two- and three-way interactions of sex, diet and time. Although statistical inference was rooted in the repeated measures models, change scores were calculated and are utilized for baseline-adjusted visual presentation of the data. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 14 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05. Reported values are means ± standard errors.

Results

Eighteen of 36 CARB females had withdrawn from the study at 12 months, as well as 18 of 30 CARB males, 14 of 36 PRO females and 9 of 28 PRO males. Total body weight, FM and LM loss and dietary intakes have been reported previously [18, 19]. Dietary intakes are reiterated briefly here, whereas body composition outcomes reported here focus on sex differences. Participants lost 8.2 % of baseline body weight (95 % CI, 7.5-8.9) at 4 mo and 10.5 % (8.9-12.0) at 12 mo, with no differences by diet, sex, or their interaction (all P > 0.2). By 4 mo, energy intake was aligned approximately at prescribed levels, and protein and carbohydrate intakes diverged according to diet as prescribed (diet x time interaction P < 0.05; Table 1). Diets were similar in energy intake across diets through the intervention, although they differed between PRO and CARB males at baseline (Table 1).

Protein intake also approached prescribed levels in the PRO (1.37 ± 0.04 g kg-1·d-1 or 29 ± 0.6 percent of energy) and CARB (0.82 ± 0.03 g kg-1 ·d-1 or 18 ± 0.3 percent of energy) groups at 4 mo. Protein intake was similar at 4 and 12 mo (Table 1). Fat intake increased slightly from 4 to 12 mo irrespective of diet (P < 0.05). Carbohydrate intake declined in PRO participants to accommodate additional protein, as expected, though fat intake was mildly elevated in PRO vs. CARB participants (Table 1). Intakes of all nutrients were generally higher in men (Table 1). Physical activity was similar across diet and sex and timepoints (P > 0.10).

Although men lost more total weight than women (P = 0.04 for sex x time interaction), this effect was eliminated when weight loss was expressed as a percentage of baseline weight (Table 2). Significant interactions for both diet x time (P = 0.03) and sex x time (P < 0.01) were observed for loss of whole body FM, although diet effects within each time point were not significant (Table 1). A similar pattern emerged for LM (P = 0.03 for diet x time; P < 0.01 for sex x time). The three-way interaction of diet x sex x time was not significant at any site for LM or FM.

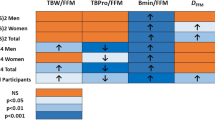

No diet or diet x time interaction effect was observed on total body LM or appendicular LM. A decline in %Fat was found for women and men in both diets at the whole body, trunk and legs (Figure 1). Though %Fat improved for all subjects, improvements were more pronounced in men compared to women and in PRO compared to CARB participants (P < 0.01 for diet x time and sex x time effects; Figure 1). The three-way interaction of diet x sex x time was not significant at any site.

Change in % fat mass of the whole body (WB), trunk and legs in adult men and women prescribed to a higher protein (PRO) or high carbohydrate (CARB) diet. ∆: PRO males, ○: PRO females, ▼: CARB males, ●: CARB females. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 130, α = 0.05. Analysis performed using an unstructured linear mixed model including diet, sex, time and their two- and three-wayinteractions. No significant sex x diet x time interactions were observed. a significant effect of sex within time. b significant effect of diet within time. c all groups differ from respective baseline values.

The share of total body fat stored at the trunk was also higher at baseline in men (mean difference 7.0 ± 0.87 %, P < 0.01), and experienced a greater decline in men (change of −3.0 ± 0.54 % at 12 mo) compared to women (change of −1.8 ± 0.32 % at 12 mo; P = 0.02 for sex x time interaction). As expected, the share of total fat carried in the legs was higher in females (mean difference at baseline 7.2 ± 0.85 %, P < 0.01), but the interaction of sex and time was not significant (P = 0.16). The effect of diet and its interactions with sex and time were not significant for either of these parameters.

The relative site-specific loss of fat mass was compared using the ratio of trunk fat to leg fat. The ratio was higher in men at baseline (1.9 ± 0.068 vs. 1.3 ± 0.040, P < 0.01 for difference), but declined more rapidly in men over the course of the intervention, irrespective of diet (Figure 2).

Change in the ratio of trunk to leg fat mass for adult men and women prescribed a higher protein (PRO) or a high carbohydrate (CARB) diet. ∆: PRO males, ○: PRO females, ▼: CARB males, ●: CARB females. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 130, α = 0.05. Analysis performed using an unstructured linear mixed model including diet, sex, time and their two- and three-way interactions. No significant sex x diet x time interactions were observed. a significant effect of sex within time. c all groups differ from respective baseline values.

Discussion

The present study investigated sex differences in body compositional changes in response to a PRO weight loss diet compared to an isocaloric CARB weight loss diet in middle-aged adults. The main finding of this study was that diet and sex impacted changes in body composition independently and additively for the whole body, trunk and leg FM. No interactions of diet and sex were found on either whole body or regional body composition suggesting that males and females respond similarly to caloric restriction diets differing in protein content. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether a higher protein diet can confer differences between men and women in degree or location of FM and LM reductions.

Some studies suggest that higher levels of protein in the diet may have a direct influence on degree of lean mass lost during energy restriction [9, 10, 14]. Because men generally have more LM, their absolute protein needs may be greater than in women; therefore, providing adequate protein during weight loss may be important in preserving LM. Contrary to our present results, Farnsworth et al., found that LM is preserved in women, but not in men on a higher protein diet [9]. The study by Farnsworth [9] was limited by a small number of men and a shorter duration (16 weeks total) than in the present study. Also, different protein levels between studies may partly explain the different findings. The higher protein diet in the Farnsworth study provided approximately 110 g protein/d for both men (~1.0 g kg-1 d-1) and women (~1.2 g kg-1 d-1) [9].

Conversely, protein intakes in the current study were slightly higher in men (PRO: 130 g d-1, 1.3 g kg -1 d-1. CARB: 75 g d-1, 0.8 g kg-1 d-1) than in women (PRO: 100 g d-1 or 1.2 g kg-1 d-1. CARB: 64 g d-1, 0.7 g kg-1 d-1). One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that a threshold for LM maintenance was met in the current study, but not by the slightly lower protein intake relative to body weight reported by Farnsworth [9]. A threshold effect for maintaining LM during negative energy balance has not been characterized; however, a previous report in post-menopausal women demonstrated that for every additional 0.1 g kg -1 d-1 of dietary protein intake, 0.62 kg LM was preserved during a 20-wk weight loss intervention [23]. The range of protein intakes was below the current RDA for protein intake [23]. Notably, a subsequent study demonstrates that protein intake of 1.5 g kg-1 d-1, which is above the current RDA, suppresses proteolysis thus inhibiting loss of lean mass [24, 25].

Although men lost more total weight than women, when expressed relative to baseline body weight both sexes lost similar amounts of weight (~10 %). Importantly, we found that more of the total weight loss was derived from fat relative to LM in men (63 % and 77 % for CARB and PRO, respectively) than women (57 % and 67 %), and that more fat relative to lean was lost in PRO participants of both sexes. This is similar to previous findings [26], whereas other studies report no such effect of diet [9]. Although some studies show that sex does not influence the composition of weight loss from energy restriction [27, 28], this finding is inconsistent [29, 30]. In men, our results are similar to those reported in the literature, with the expectation that ~70 % of weight loss is comprised of FM during dieting alone [31]. Women in the PRO group also compared similarly to what was expected for FM loss, while the women in the CARB group lost less FM. However, we found no significant impact of the diets on sex differences in whole body weight, FM or LM loss.

Given the well-known association between central adiposity and CVD and metabolic complications [32–35], identifying changes in body fat distribution with weight loss is of particular interest. It is well established that women have greater levels of adiposity than men [1], and the distribution of fat differs, with men storing a greater proportion centrally and women in the gluteofemoral region [1]. However, with regard to the fat patterning, sex differences in changes in regional adipose depots through energy restriction are not well characterized. It appears that while both men and women lose FM from the abdominal area [7, 36] and the femoral region [9], men may lose more abdominal fat [9, 37] and women lose more femoral FM [7], even when matched on total weight and total fat loss [29]. Our data support the sex disparity in region of fat loss. Although both men and women reduced the relative fat of the whole body, trunk and leg, and no significant sex difference in the effect of the diets was found, these improvements are more pronounced in men, with the greatest change found in the PRO male group. Further assessment of the changes in the distribution of fat loss, indicated men experienced a reduction in the ratio of trunk fat to leg fat, suggesting that a greater degree of fat loss was derived from the central region.

Little evidence is available in the literature on potential underlying mechanisms to explain regional differences in body composition changes between men and women undergoing weight loss. However, one possible explanation for differences between men and women in their response to a higher protein weight loss diet could be related to a greater post-meal Diet Induced Thermogenesis (DIT) found in men compared to women [38, 39]. Another explanation could be related to recent findings from an animal study, which showed that the protein content of a meal is the trigger for muscle protein synthesis, and this was shown to significantly increase energy expenditure, as measured by changes in adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) and the signaling molecule adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [40]. Importantly, the content of the branch chained amino acid leucine in a higher protein diet plays a key role in mechanisms that support the preservation of lean mass [41]. Other mechanisms, such as hormonal differences between sexes, may be responsible for the observed differences in body composition changes between men and women. Unfortunately, data from the present study are insufficient to examine underlying mechanisms.

Even though the sample size in the present study is larger than in most other studies, a diet by gender interaction may be only detectable with a larger baseline sample, which suggests that the effect of diet on sex differences in composition may be small. Men may benefit more from a greater protein intake during weight loss due to greater LM compared to women. A study designed to provide protein per kg of LM rather than in absolute terms or per kg body weight could elucidate this issue. Another consideration for our results is that the age range in the current study spans across menopausal status in women, potentially allowing hormonal status to influence the distribution of fat loss. Although our study was not designed to evaluate the impact of hormonal status or age per se on treatment effects, weight loss treatments that maximize FM loss while maintaining LM, especially in the legs are critical to combat the rising incidence of sarcopenic obesity. Indeed, statements in the literature regarding body composition and older adults indicate that this is a high research priority [11, 42]. Lastly, more accurate measures of regional body composition, such as with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, could elucidate differences in loss of FM from the abdominal vs. gluteofemoral regions between men and women and perhaps differences in changes in LM, especially in the lower body which is critical for physical function.

In summary, although we found no significant sex differences in the effects of diet on how much and where FM and LM are reduced during weight loss states, there is some evidence that protein intake levels may impact the amount of LM preserved during weight loss, perhaps regardless of sex. Clearly, further intervention studies, designed to assess interactive effects of sex and macronutrient content of the diet, are required to determine whether protein intake recommendations under energy restriction need to be adjusted to help maintain LM while losing FM, especially in populations such as older adults who are at higher risk for sarcopenia.

Funding sources

Illinois Council on Food and Agricultural Research, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, The Beef Board, Kraft Foods, National Science Foundation (PI: Layman).

References

Nielsen S, Guo Z, Johnson CM, Hensrud DD, Jensen MD: Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J Clin Invest. 2004, 113: 1582-1588.

Dubnov G, Brzezinski A, Berry EM: Weight control and the management of obesity after menopause: the role of physical activity. Maturitas. 2003, 44: 89-101. 10.1016/S0378-5122(02)00328-6.

Lemieux S, Prud'homme D, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP: Sex differences in the relation of visceral adipose tissue accumulation to total body fatness. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993, 58: 463-467.

Kvist H, Chowdhury B, Grangard U, Tylen U, Sjostrom L: Total and visceral adipose-tissue volumes derived from measurements with computed tomography in adult men and women: predictive equations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988, 48: 1351-1361.

NHLBI: Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. Institute NHLaB. 1998, MD, Bethesda

Janssen I, Fortier A, Hudson R, Ross R: Effects of an energy-restrictive diet with or without exercise on abdominal fat, intermuscular fat, and metabolic risk factors in obese women. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 431-438. 10.2337/diacare.25.3.431.

Mauriege P, Imbeault P, Langin D, Lacaille M, Almeras N, Tremblay A, Despres JP: Regional and gender variations in adipose tissue lipolysis in response to weight loss. J Lipid Res. 1999, 40: 1559-1571.

Newman AB, Lee JS, Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Nevitt M, Harris TB: Weight change and the conservation of lean mass in old age: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 82: 872-878. quiz 915–876

Farnsworth E, Luscombe ND, Noakes M, Wittert G, Argyiou E, Clifton PM: Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 78: 31-39.

Krieger JW, Sitren HS, Daniels MJ, Langkamp-Henken B: Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression 1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 83: 260-274.

Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S: Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 1849-1863. 10.1038/oby.2005.228.

Due A, Toubro S, Skov AR, Astrup A: Effect of normal-fat diets, either medium or high in protein, on body weight in overweight subjects: a randomised 1-year trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 1283-1290. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802767.

Skov AR, Toubro S, Rønn B, Holm L, Astrup A: Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999, 23: 528-536. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800867.

Layman DK, Evans E, Baum JI, Seyler J, Erickson DJ, Boileau RA: Dietary protein and exercise have additive effects on body composition during weight loss in adult women. J Nutr. 2005, 135: 1903-1910.

Noakes M, Keogh JB, Foster PR, Clifton PM: Effect of an energy-restricted, high-protein, low-fat diet relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet on weight loss, body composition, nutritional status, and markers of cardiovascular health in obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81: 1298-1306.

Bowen J, Noakes M, Clifton PM: Effect of calcium and dairy foods in high protein, energy-restricted diets on weight loss and metabolic parameters in overweight adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005, 29: 957-965. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802895.

Layman DK: Dietary Guidelines should reflect new understandings about adult protein needs. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2009, 6: 12-10.1186/1743-7075-6-12.

Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D, Griel A, Psota T, Kris-Etherton P: A Moderate-Protein Diet Produces Sustained Weight Loss and Long-Term Changes in Body Composition and Blood Lipids in Obese Adults. J Nutr. 2009, 139: 514-521. 10.3945/jn.108.099440.

Thorpe MP, Jacobson EH, Layman DK, He X, Kris-Etherton PM, Evans EM: A diet high in protein, dairy, and calcium attenuates bone loss over twelve months of weight loss and maintenance relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate diet in adults. J Nutr. 2008, 138: 1096-1100.

Institute of Medicine FaNB: Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. 2002, National Academy Press, Washington DC

NHLBI: Third report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. 2001, ATP III, Washington DC

Agriculture UDo, Services UDoHaH: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. ed 4th. 2005, Health and Human Services, Washington DC

Bopp MJ, Houston DK, Lenchik L, Easter L, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ: Lean mass loss is associated with low protein intake during dietary-induced weight loss in postmenopausal women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108: 1216-1220. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.04.017.

Piatti PM, Monti F, Fermo I, Baruffaldi L, Nasser R, Santambrogio G, Librenti MC, Galli-Kienle M, Pontiroli AE, Pozza G: Hypocaloric high-protein diet improves glucose oxidation and spares lean body mass: comparison to hypocaloric high-carbohydrate diet. Metabolism. 1994, 43: 1481-1487. 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90005-1.

Hoffer LJ, Taveroff A, Robitaille L, Hamadeh MJ, Mamer OA: Effects of leucine on whole body leucine, valine, and threonine metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997, 272: E1037-1042.

Parker B, Noakes M, Luscombe N, Clifton P: Effect of a high-protein, high-monounsaturated fat weight loss diet on glycemic control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 425-430. 10.2337/diacare.25.3.425.

Ballor DL, Poehlman ET: Exercise-training enhances fat-free mass preservation during diet-induced weight loss: a meta-analytical finding. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994, 18: 35-40.

Janssen I, Ross R: Effects of sex on the change in visceral, subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in response to weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999, 23: 1035-1046. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801038.

Leenen R, van der Kooy K, Droop A, Seidell JC, Deurenberg P, Weststrate JA, Hautvast JG: Visceral fat loss measured by magnetic resonance imaging in relation to changes in serum lipid levels of obese men and women. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993, 13: 487-494. 10.1161/01.ATV.13.4.487.

Wirth A, Steinmetz B: Gender differences in changes in subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat during weight reduction: an ultrasound study. Obes Res. 1998, 6: 393-399.

Garrow JS, Summerbell CD: Meta-analysis: effect of exercise, with or without dieting, on the body composition of overweight subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995, 49: 1-10.

Misra A, Vikram NK: Clinical and pathophysiological consequences of abdominal adiposity and abdominal adipose tissue depots. Nutrition. 2003, 19: 457-466. 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)01003-1.

Van Pelt RE, Evans EM, Schechtman KB, Ehsani AA, Kohrt WM: Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 282: E1023-1028.

Karelis AD, St-Pierre DH, Conus F, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Poehlman ET: Metabolic and body composition factors in subgroups of obesity: what do we know?. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89: 2569-2575. 10.1210/jc.2004-0165.

Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, Cheema P, Bahouth SW: Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology. 2004, 145: 2273-2282. 10.1210/en.2003-1336.

Weinsier RL, Hunter GR, Gower BA, Schutz Y, Darnell BE, Zuckerman PA: Body fat distribution in white and black women: different patterns of intraabdominal and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue utilization with weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001, 74: 631-636.

Luscombe ND, Clifton PM, Noakes M, Farnsworth E, Wittert G: Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on weight loss and energy expenditure after weight stabilization in hyperinsulinemic subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 27: 582-590. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802270.

Visser M, Deurenberg P, van Staveren WA, Hautvast JG: Resting metabolic rate and diet-induced thermogenesis in young and elderly subjects: relationship with body composition, fat distribution, and physical activity level. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995, 61: 772-778.

Gougeon R, Harrigan K, Tremblay JF, Hedrei P, Lamarche M, Morais JA: Increase in the thermic effect of food in women by adrenergic amines extracted from citrus aurantium. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 1187-1194. 10.1038/oby.2005.141.

Wilson GJ, Layman DK, Moulton CJ, Norton LE, Anthony TG, Proud CG, Rupassara SI, Garlick PJ: Leucine or carbohydrate supplementation reduces AMPK and eEF2 phosphorylation and extends postprandial muscle protein synthesis in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 301: E1236-1242. 10.1152/ajpendo.00242.2011.

Layman DK, Walker DA: Potential importance of leucine in treatment of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2006, 136: 319S-323S.

Alley DE, Ferrucci L, Barbagallo M, Studenski SA, Harris TB: A research agenda: the changing relationship between body weight and health in aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008, 63: 1257-1259. 10.1093/gerona/63.11.1257.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the Illinois Council on Food and Agricultural Research, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, The Beef Board, Kraft Foods, and the National Science Foundation (PI: Layman).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors’ contributions

MM and RV participated in the study coordination and data collection, and drafted the manuscript. MT performed the statistical analysis and participated in drafting the manuscript. DL, PK-E and EE conceived of and designed the study, and participated in its coordination as well as helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Dr Layman has participated in speaker bureaus for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association and the National Dairy Council.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, E.M., Mojtahedi, M.C., Thorpe, M.P. et al. Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: a randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutr Metab (Lond) 9, 55 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-55

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-55