Abstract

Robot-mediated post-stroke therapy for the upper-extremity dates back to the 1990s. Since then, a number of robotic devices have become commercially available. There is clear evidence that robotic interventions improve upper limb motor scores and strength, but these improvements are often not transferred to performance of activities of daily living. We wish to better understand why. Our systematic review of 74 papers focuses on the targeted stage of recovery, the part of the limb trained, the different modalities used, and the effectiveness of each. The review shows that most of the studies so far focus on training of the proximal arm for chronic stroke patients. About the training modalities, studies typically refer to active, active-assisted and passive interaction. Robot-therapy in active assisted mode was associated with consistent improvements in arm function. More specifically, the use of HRI features stressing active contribution by the patient, such as EMG-modulated forces or a pushing force in combination with spring-damper guidance, may be beneficial.

Our work also highlights that current literature frequently lacks information regarding the mechanism about the physical human-robot interaction (HRI). It is often unclear how the different modalities are implemented by different research groups (using different robots and platforms). In order to have a better and more reliable evidence of usefulness for these technologies, it is recommended that the HRI is better described and documented so that work of various teams can be considered in the same group and categories, allowing to infer for more suitable approaches. We propose a framework for categorisation of HRI modalities and features that will allow comparing their therapeutic benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common causes of adult disabilities. In the United States, approximately 795,000 individuals experience a new or recurrent stroke each year, and the prevalence is estimated at 7,000,000 Americans over 20 years of age [1]. In Europe, the annual stroke incidence rates are 141.3 per 100,000 in men, and 94.6 in women [2]. It is expected that the burden of stroke will increase considerably in the next few years [3]. The high incidence, in combination with an aging society, indicates future increases in incidence, with a strong impact on healthcare services and related costs.

Impairments after stroke can result in a variety of sensory, motor, cognitive and psychological symptoms. The most common and widely recognised impairments after stroke are motor impairments, in most cases affecting the control of movement of the face, arm, and leg on one side of the body, termed as hemiparesis. Common problems in motor function after hemiparetic stroke are muscle weakness [4–6], spasticity [4–6], increased reflexes [4], loss of coordination [4, 7] and apraxia [4]. Besides, patients may show abnormal muscle co-activation, implicated in stereotyped movement patterns, which is also known as ‘flexion synergy’ and ‘extension synergy’ [8, 9]. Concerning the upper extremity, impaired arm and hand function contributes considerably to limitations in the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL). One of the goals of post stroke rehabilitation is to regain arm and hand function, since this is essential to perform activities of daily living independently.

Stroke rehabilitation

Stroke rehabilitation is often described as a process of active motor relearning that starts within the first few days after stroke. Recovery is characterized by a high inter-individual variability, and it occurs in different processes. Some of the first events following nervous system injury are recovery due to restitution of non-infarcted penumbral areas, reduction of oedema around the lesion, and resolution of diaschisis [10–12], and comprise spontaneous neurological recovery. A longer term mechanism involved in neurological recovery is neuroplasticity, caused by anatomical and functional reorganisation of the central nervous system. Additionally, motor recovery after stroke may occur through compensational strategies. Compensation is defined as behavioural substitution, which means that alternative behavioural strategies are adopted to complete a task. In other words, function will be achieved through alternative processes, instead of using processes of ‘true recovery’ alone [11–13].

Treatment approaches

Many treatment approaches have been developed to aid motor recovery after stroke. These interventions are different in their approach to achieve functional gains. For instance, in the 1950s and 1960s, the so-called neurofacilitation approaches were developed. From these approaches based on neurophysiological knowledge and theories, the Bobath Concept, or neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT), is the most used approach in Europe [14–16]. This approach focuses on normalizing muscle tone and movement patterns, guided by a therapist using specific treatment techniques, in order to improve recovery of the hemiparetic side. Gradually, focus shifted towards the motor learning, or relearning approach [17]. Others have referred to these methods as the task-oriented approach. These new methods of clinical practice are based on the notion that active practice of context-specific motor tasks with suitable feedback will support learning and motor recovery [11, 17].

Overall, there is a lack of convincing evidence to support that any physiotherapy approach is more effective in recovery than any other approach [15, 16, 18]. However, in a review of Langhorne et al. [19], it is stated that some treatments do show promise for improving motor function, particularly those that focus on high-intensity and repetitive task-specific practice. Moreover, research into motor relearning and cortical reorganisation after stroke has showed a neurophysiologic basis for important aspects that stimulate restoration of arm function [20–23]. These important aspects of rehabilitation training involve functional exercises, with high intensity, and with active contribution of the patient in a motivating environment.

Rehabilitation robotics

Robot-mediated therapy for the upper limb of stroke survivors dates back to the 1990s. Since then a number of robotic devices have become commercially available to clinics and hospitals, for example the InMotion Arm Robot (Interactive Motion Technologies Inc., USA, also known as MIT-Manus) and the Armeo Power (Hocoma, Switzerland). Robotic devices can provide high-intensity, repetitive, task-specific, interactive training. Typically, such robots deliver forces to the paretic limb of the subject while practicing multi-joint gross movements of the arm. Most of the robotic devices applied in clinical trials or clinical practice offer the possibility of choosing among four modalities for training: active, active-assisted, passive and resistive. These terms relate to conventional therapy modes used in clinical practice and refer to subject’s status during interaction. Passive training for example refers to subject-passive/robot-active training such as in continuous passive motion (CPM) devices. The choice of modality (−ies) in each protocol is ultimately made by researchers/therapists.

There is evidence that robotic interventions improve upper limb motor scores and strength [24–26], but these improvements are often not transferred to performance of activities of daily living (ADL). These findings are shared among the most recent studies, including the largest randomised controlled trial related to robot-therapy to date [27]. A possible reason for a limited transfer of motor gains to ADL is that the earlier studies on robot-mediated therapy have only focused on the proximal joints of the arm, while integration of distal with proximal arm training has been recognized as essential to enhance functional gains [28, 29].

Another issue involved in the limited transfer of motor gains to ADL improvements in robot-mediated therapy research may relate to the large variety of devices and protocols applied across clinical trials. Lumping together many devices and protocols does not provide knowledge of the effectiveness of individual components, such as which of the available therapeutic modalities result in the largest effect [25]. Consequently, in literature there has been a transition towards reviews focusing on selective aspects of robot-mediated therapy, rather than its overall effectiveness [30–33].

A major step in that direction is the description of different control and interaction strategies for robotic movement training. In a non-systematic review, Marshal-Crespo et al. [34] collected a set of over 100 studies involving both upper and lower limb rehabilitation. They made a first distinction between assistive, challenging and haptic-simulating control strategies. They also described assistive impedance-based controllers, counterbalancing, EMG-based and performance-adapted assistance. Furthermore, they highlighted the need for trials comparing different interaction modalities. However, that review only included articles up to the year 2008 while much more new information has become available in the recent years.

Loureiro et al. [35] described 16 end-effector and 12 exoskeleton therapy systems in terms of joints involved, degrees of freedom and movements performed [35]. However, this non-systematic review did not report about the effects of the interventions or identify the interaction or control strategies used. Specifically focusing on training of the hand, Balasubramanian et al. [36] identified 30 devices for hand function and described them in terms of degrees of freedom, movements allowed, range of motion, maximum force (torque) and instrumentation. Among these devices, eight showed an improvement in functional use of the affected hand, in terms of increased scores on the Action Research Arm Test, Box and Block test or Wolf Motor Function Test [36]. Understanding and specifically targeting mechanisms underlying recovery of the entire upper limb after stroke is essential to maximize improvements on function or even activity level.

This literature study works towards clarifying the definitions adopted in robotic control and interaction strategies for the hemiparetic upper extremity (including both proximal and distal arm segments), and identifying the most promising approaches. The objective of this systematic review is to explore and identify the human robot interaction mechanisms used by different studies, based on the information provided in literature. We propose a framework to support future categorisation of various modalities of human-robot interaction and identify a number of features related to how such strategies are implemented. In addition, we will compare clinical outcome in terms of arm function and activity improvements associated with those interactions, which allows us to identify the most promising types of human robot interactions.

Methods

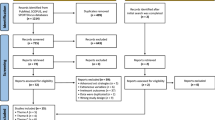

We conducted a systematic literature search on PubMed with keywords including stroke, robot and arm, upper limb, shoulder, elbow, wrist or hand. Detailed information about the search strategy is provided in Additional file 1: Appendix 1. We included full journal papers written in English about robotic training of (any part of) the upper limb. These included either uncontrolled (pre-post design) or (randomised) controlled trials, in which a group of at least four subjects received robot-mediated training. In addition, training outcome must be statistically evaluated (either pre- or post-treatment for the single group or a difference between groups). In cases where results from the same subjects were presented (partially) in other studies (e.g. a pilot study and the definitive protocol) we retained the study with the largest number of participants or the most recent study, if the number of participants were the same. Also, we discarded those studies where other interventions were applied during robot-mediated exercise (e.g. functional electrical stimulation). Two independent reviewers (AB and SN) conducted the search and selected the appropriate articles by discarding those articles which did not meet the selection criteria, based on title first, abstract second and subsequently using full-text articles. In case of doubt, the article was included in the next round of selection. After full-text selection, the two reviewers compared their selections for consensus. For each article, only those groups of subjects that were treated with a robotic device were included. Since some studies compared several experimental groups that differed by subject type, device used or experimental protocol, the number of groups did not match the number of articles. Thus, we refer to number of groups rather than number of studies.

For each group we filled a record in a structured table. Since the outcome of an intervention can be influenced by many factors, such as the initial level of impairment or the frequency and duration of the intervention, this table contains an extensive set of information (presented in Additional file 2): device used; arm segments involved in training; time post-stroke; number of subjects per group; session duration; number of weeks training; number of sessions per week; total therapy duration; modality (−ies) and features of HRI; baseline impairment measured as average Fugl-Meyer score; and clinical outcome in terms of body functions and activity level. Arm segments involved were categorised as one (single arm segment) or more (multiple arm segments) of shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist and hand, in which forearm represents pro/supination movement at the radio-ulnar joint. Time since stroke was categorised according to Péter et al. [37], considering the acute phase as less than three months post stroke, the sub-acute phase as three to six months post stroke and the chronic phase as more than six months post stroke.

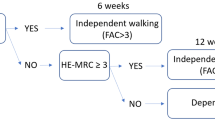

The main focus of this work is on the interaction between the subject and the robot. Table 1 categorises different ways of intervention commonly found in existing robot-mediated therapy (termed as ‘training modalities’ in this work). In active mode, performance arises from subject contribution only, whereas in passive mode the movement is performed by the robot regardless of subject’s response. In assistive modality, both subject and robot contribution affect movement performance. Passive-mirrored mode applies to bimanual devices, when the movement of the affected side is guided based on active performance of the unimpaired side. In active-assisted mode, the subject is performing actively at the beginning of the movement and the robot intervenes only when given conditions are met (e.g. if the target has not been reached within a certain time), leading to systematic success. In corrective mode instead, in such a case the robot would stop the subject to let then reprise active movement. In path guidance mode, the subject is performing actively in the movement direction, and the robot intervention is limited to its orthogonal direction. Finally, in resistive mode, the robot makes the movement more difficult by resisting the movement received from the subject. We categorised each group according to these modalities. Note that some terms refer to the subject status (i.e. “passive” and “active”), others to the robot behaviour (e.g. “resistive”).

However, these categories are not specific enough to classify such different interventions. For example, in the case of reaching movements, the assistive modality would refer to both cases where the robot is providing weight support or applying target-oriented forces. The terms commonly describing modalities of robot-mediated therapy (such as passive, active-assisted, resistive) had to be revised to provide more specific definitions in order to proceed with unambiguous classification. We therefore categorised all the modalities in a different way, specifically based on the features of their implementation. To do so, we identified the following specific technical features used to implement a certain modality (termed ‘HRI features’ in this work): passive, passive-mirrored, moving attractor, assistive constant force, triggered assistance, pushing force (in case of delay), EMG-proportional, tunnels, spring-damper guidance, spring and damper against movement. These categories are defined in detail in Table 2. Note that neither training modalities nor features of HRI are mutually exclusive categories, since groups might have been tested with several training modalities, and each modality might involve the presence of more than one HRI feature. We propose the classification of training modalities and HRI features adopted in this work as a framework for classification for future studies. This is an open framework, so that as new modalities or features are developed and tested, specific categories could be added, to be further referred.

We related clinical outcome to factors as segments of the arm trained, time since stroke and modalities and HRI features. We assessed clinical outcome as whether reported improvements were statistically significant or not, for each measure. Outcome was considered separately for body functions and structures (e.g., Fugl-Meyer, Modified Ashworth Scale, kinematics) and activities (e.g., Action Research Arm Test, Wolf Motor Function Test, Motor Activity Log), according to ICF definitions [38]. We categorized each outcome measure to either body functions or activities as defined by Sivan et al. [39] and Salter et al. [40–42]. A group was considered to have shown improvement when at least two-thirds of all the outcome measures within a specific category (of either body functions or activity level) had improved significantly.

Results

In September 2013, our search led to a total of 423 publications. The first two rounds of filtering, based on title and abstract, led to a set of 126 articles. After screening full-text articles, 74 studies were included, with a total of 100 groups treated with robots. Of the 74 studies, 35 were randomised controlled trials and 39 were clinical trials (pre-post measurement), involving 36 different devices. Group sizes ranged from 5 to 116 subjects, with a total of 1456 subjects. Table 3 presents a summarised overview of all included studies, grouped by device. Detailed information for each group is given in the table in Additional file 2: Appendix 2.With respect to stages of stroke recovery (Figure 1a), 73 of the 100 groups included patients in the chronic stage, 17 involved patients in the acute stage, and four groups involved patients in the sub-acute stage. In six cases subjects at different stages of recovery were included in the same group or no information about time since stroke was provided. The average FM score at inclusion among groups of acute subjects was 17.7 ± 12.7 and 25.9 ± 9.5 among chronic subjects. The higher average score for subacute subjects (29.3 ± 7.8) is possibly an outlier due to the small number of observations.

When considering the arm segments (Figure 1b), we observed that training involved shoulder movements for 71 groups, elbow flexion-extension for 74 groups, wrist movements for 32 groups, forearm pronation-supination for 20 groups, and hand movements for 20 groups. Training rarely focused on a single part of the arm, with four groups specifically trained for elbow [86, 90, 92, 93], five groups for wrist [73, 85, 87, 88] and six groups for hand [76–79, 116] movements. Training of movements involving the entire upper limb (as those performed during ADL) is not highly recurrent (seven groups) [27, 49, 84, 108, 109, 113].We then considered the modalities used, and Figure 2 shows an overview of the frequency of usage of each modality. In 63 groups more than one modality was used. Training included active-assistive modality in 63 groups. Twenty-eight groups were trained in assistive modality. Passive training was included in 35 groups. Active and resistive modalities were involved less frequently, in 29 and 22 groups, respectively. The passive-mirrored modality was used in 14 groups, path guidance in seven groups and corrective strategy in five groups.

We also considered these frequencies with respect to the stage of recovery. Passive and passive-mirrored modality are more recurrent for acute than for chronic subjects (with 77 and 24% of the groups of acute trained with these modalities, versus the respective 21 and 11% of chronic subjects). Similarly, modalities more suitable for less impaired subjects as resistive and active are more recurrent among chronic (23 and 30% of the cases, respectively) than within acute subjects (18% for both modalities). Instead, the choice among modalities was not affected by the level of impairment (as measured by FM score). As an instance, subjects trained with passive modality had an average FM of 27.1 ± 12.8 at inclusion versus 23.9 ± 9.6 of those who did not receive this treatment. Subsequently, we considered the HRI features. In 26 groups there was no clear description or reference to the intervention. Passive and passive mirrored modalities showed the same frequency as reported for the previous classification (35 and 14 groups) as the definition of these categories coincides in the two classifications. Triggered assistance, spring-damper along movement and a pushing force followed in order of frequency after passive training (with respectively 26, 18 and 15 groups). Assistance was delivered as a constant force in twelve groups, as a force proportional to the distance from a moving attractor in seven groups and proportional to the EMG activity in eight groups. Resistance was implemented as elastic forces in ten groups and viscous in eight groups. All included studies, except for one, fell in the definitions we provided a priori for categorizations. Recently, a particular paradigm of HRI (error-augmentation) showed clinical benefits [111], but it did not fit in any of the modalities we described a priori. In this modality, the robot tends to displace the subject’s hand from the optimal trajectory by applying a curl force field to the hand. This constitutes a new, different modality, which benefits could be investigated as more studies using it become available.

We then considered the outcome measures, although the positive outcome of an intervention depends on many factors such as the initial level of impairment of the subjects, frequency and duration of the treatment, baseline impairment (for which detailed information is available in Additional file 2: Appendix 2).

Overall, 54 of 99 groups (55%) showed significant improvements in body functions. Twenty-two of the 54 groups who measured outcomes related to the activity level (41%), showed improvements on this level.

With respect to time after stroke and observed that among acute stroke patients, 59% of the groups showed improvements on body functions, and 33% on activity level. In chronic stroke patients, 53% of the groups improved on body functions, and 36% on activity level. For the sub-acute phase, two out of four groups improved on body functions, and two out of three groups improved on activity level.

About outcome for arm segments trained, improvements on body function seemed to be equally distributed between different parts of the arm, but we observed that training of the hand seems to be most effective on the activity levels, with 60% of the groups showing improvements.

Table 4 shows the outcome for different modalities and features of HRI. When relating clinical outcome to specific training modalities, most of the studies (63 of the 100 groups) included multiple modalities in one training protocol. Among them, those including path-guidance (six of the seven groups) and corrective modality (four of the five groups) resulted in the highest percentage of groups improved for body functions (86% and 80%, respectively). However, this may be affected by the limited number of groups. Besides, these groups did not show persistent improvements on activity level. It is noteworthy that the most consistent improvements on activity level were reported for training including the active modality (nine of the 15 groups; 60%).

The effect of a single training modality (i.e., only one modality applied in a training protocol) was investigated in the remaining 37 groups: 24 groups applied only the active assistive modality, four groups trained with passive movement only, six groups applied only assistive training, two groups with passive mirrored and one group with resistive modality only. The active-assisted modality seemed to have the most consistent impact on improvements in both body functions and activities: 14 of the 24 groups (58%) [43, 44, 49, 60, 84, 86, 88, 90, 96, 100, 101] showed significant improvements in body functions. Regarding activities, four of the 11 groups (36%) [43, 79, 84, 96] measuring activity level showed significant improvements after active-assisted training. Training exclusively in passive mode was associated with improvement in body functions for two of four groups (50%) [76, 103] and in activities for one of three groups (33%) [103]. With the exclusive assistive modality, two of the six groups (33%) showed significant improvements in body functions [50, 61]. In passive-mirrored mode (two groups) and resistive mode (one group), none of the groups showed significant improvements in either body functions or activities.

We also considered whether the inclusion of a modality led to different outcome for subjects at different phases of recovery. Due to the small number of observations for subacute subjects, we neglect those results. Instead, for acute subjects we found that modalities with better outcome on body functions were active (2 out of 3 groups, 67%), assistive (4 out of 6 groups, 67%), active-assistive (5 out of 10 groups, 50%) and passive (6 of 13 groups, 46%). For subjects in acute phase, inclusion of passive mirrored and resistive modality did not lead to improvements in body functions (in none of the 4 and 3 groups, respectively). These results differ from subjects in chronic phase, where inclusion of passive-mirrored modality led to improvement in 75% of the groups (6 out of 8), while the inclusion of resistive modality was effective on 71% of the groups (12 of 17). The path guidance modality led to the best results for chronic patients (6 out of 6 groups improved on body functions). Results for other modalities are similar among them, with all the other modalities being effective on about 60% of the groups. The effectiveness is generally lower on the activity level. For acute subjects, there are not many observations for most of the modalities. Instead, for chronic subjects the inclusion of active modality (62%, 8 out of 13 groups) seemed to perform better than all the others, which were effective in about 40% of the cases. Exclusion to this is the passive-mirrored mode, for which only 1 of the 8 groups (12.5%) improved on activity level.

When we considered the specific HRI features used in the 14 groups who improved on body functions with active-assistance as single modality, five groups used triggered assistance, four groups EMG proportional, four groups a pushing force in combination with spring-damper guidance movement, and one group an assistive constant force. The four groups in active-assisted mode who improved on activity level used triggered assistance (two groups), assistive constant force (one group), and for one group it was not clear which feature of HRI was used.

When considering the clinical outcomes associated with those HRI features within the whole studies reviewed, as for the modalities most of the studies included multiple features of HRI in one training protocol (58 groups). Regarding multiple features of HRI applied in training protocols, those including EMG-proportional, tunnels and damper against movement resulted in the highest percentage of groups improved for body functions (100%, 100% and 75%, respectively). This is followed by spring damper guidance, pushing force, triggered assistance and spring against movement, showing an improvement in body functions in 61% (11 of 18 groups), 60% (9 of 15 groups), 60% (15 of 25 groups) and 60% (6 of 10 groups) respectively. However, the limited number of groups might be affecting this result, especially concerning outcomes at activity level.

The effect of a single feature of HRI (i.e. only one feature of HRI applied in a training protocol) was investigated in the remaining 42 groups. The most common single HRI feature was triggered assistance (TA), which was used in 14 groups. However, only seven of these showed significant improvements in body functions [43, 44, 96, 97, 100–102], and in the case of activities, four of the nine groups who measured outcomes on activity level (44%) improved [43, 96, 97]. The EMG-proportional feature the sole was used in five groups, all showing improved body functions (100%) [85, 86, 88, 90, 116], but only one of two groups showed improved activities [116]. A constant assistive force only was used in five groups, of which only one group showed improvements in both body functions and activities [84]. So, when focusing on single features, EMG proportional feature seems most promising, followed by passive and triggered assistance. However, the other HRI features that had good results in combined protocols with multiple features (tunnels, damper against movement, spring damper guidance and pushing force) have not been investigated as single feature of HRI at all. Nevertheless, a common aspect can be derived from the features with most consistent effects, indicating that the active component is promising for improving arm function. For activities, no conclusive answers can be drawn, because of the limited number of studies who have investigated this effect using a single feature at this point. This is also true for analysis of the relation of separate training modalities/HRI features with mediating factors such as initial impairment level, frequency and duration of training, etc.

Discussion

Our results highlight that robot-therapy has focused mostly on subjects in chronic phase of recovery, while considerably less studies involved subjects in acute and in sub-acute phases (73, 17 and four groups, respectively). However, our results indicate that patients across all stages of recovery can benefit from robot-mediated training.

Despite the evidence that training the hand (alone) is accompanied with improvement of both hand and arm function, we observed that many robot-therapy studies focused on proximal rather than on distal arm training. Also, only a limited number of studies focused on training the complete upper limb involving both proximal and distal arm movements, while there is evidence of benefits for training arm and hand together rather than separately [117]. Additionally, it is known that post-stroke training should include exercises that are as “task-specific/functional” as possible to stimulate motor relearning, which further supports inclusion of the hand and with proximal arm training [28, 29]. Additionally, to allow proper investigation of the effect of such functional training of both proximal and distal upper extremity simultaneously, outcome measures at activity level have to be addressed specifically, besides measurements on the level of body functions. However, in all but one study [91] outcomes related to body function were measured, but the effects of robotic training on activities were assessed in only 54 of 100 groups. This prevents adequate interpretation of the impact of robotic therapy and associated human robot interactions on functional use of the arm at this point.

When focusing on the modality of interaction, we observed that training protocols only occasionally included only one training modality, which makes it difficult to examine the effect of one specific modality. This also hindered a detailed analysis of separate effects per training modality and especially their relation with mediating factors such as initial impairment level, frequency and duration of training, etc.

Only a limited number of studies aimed at comparing two or more different robotic treatments. The first of those studies hypothesized benefits of inserting phases of resistive training in the therapy protocol [51]. Subjects were assigned to different groups, training with active-assistive modality only, resistive only or both. There were no significant effects from incorporating resistance exercises. Another study [69] compared a bimanual therapy (in passive mirrored mode) with a unimanual protocol which included passive, active-assistive and resistive training. Again, there were no significant differences between groups in terms of clinical scores. In a different study, active-assistive training delivered with an EMG-controlled device showed larger improvements (in Fugl-Meyer, Modified Ashworth Scale and muscle coordination) with respect to passive movement in wrist training [85]. Assistive forces may also be provided as weight support. In this case, subjects benefitted from a progressive decrease of such assistance, along therapy [80].

Even though there are a limited number of studies comparing separate training modalities, the available data indicated that robot-mediated therapy in active assisted mode led most consistently to improvements in arm function. Whether this mode is actually the most effective one cannot be stated at this point due to lack of a standard definitions used by different studies. It is remarkable that the application of two of the least adopted modalities, i.e. path guidance and corrective, did consistently result in improved clinical outcome. Although this effect might be due to the small number of studies which included them, this suggests that one way to be pursued in future research in order to improve the results of robotic rehabilitation is utilising robot’s programmable interaction potentials, rather than just mimicking what a therapist can do (passive, active-assisted, even resistance to some extent). Experimental protocols including more than one modality should also be sought, and the combined effect of different modalities should be investigated. As an instance, patients might switch from passive toward active modality as recovery progresses.

With respect to the specific strategy (HRI feature) for providing assistance when applying active assistive training, the findings from this review indicate that a pushing force in combination with lateral spring damper, or EMG-modulated assistance were associated with consistent improvements in arm function across studies, while triggered assistance showed less consistent improvement. It is suggested that modalities that stress the active nature of an exercise, requiring patients to initiate movements by themselves and keep being challenged in a progressive way throughout training (i.e., taking increases in arm function into account by increasing the level of active participation required during robot-therapy), do show favourable results on body function level.

The training modalities referred mainly to the description given by the authors of the reviewed studies, but in absence of a uniform definition for identifying robot-human contributions, groups often named the mechanisms used according to their preference and understanding of these mechanisms. Attention to the interaction mechanism between a person and robot is sometimes so limited that often authors did not even mention such mechanisms in their publications (this happened for 26 out of 100 groups). Given a commonly accepted categorisation for these modalities, researchers are then able to compare usefulness of different human-robot interaction mechanisms. It is thought that by providing a common-base for interaction, a larger body of evidence can be provided, i.e. via a data-sharing paradigm, to understand the full potential of robot-mediated therapy for improving arm and hand function after stroke. Ultimately, this can support better integration of robot-mediated therapy in day-to-day therapeutic interventions.

About the effectiveness of different modalities, considering that cortical reorganization and outcome after stroke rehabilitation is positively associated with active, repetitive task-specific (i.e., functional) practice [28, 29], human robot interactions stressing these features are preferred. In addition, there is a strong computational basis to push towards delivering minimally assistive therapy [118]. In contrast to this, passive movement is very recurrent, as it may provide more severely impaired subjects with the opportunity to practice. If this is the case, one way to improve the outcome of the therapy in this situation is to tailor the exercise to individual needs while stimulating active contribution of the patient as much as possible, rather than passively guiding to systematic success. Nevertheless, due to the large variety and heterogeneity in training modalities applied (i.e. contents of the intervention), it wasn’t possible to draw conclusions about the role of these additional mediating factors per training modality. More research about comparing different training modalities (with only one specific modality per group) is needed to answer more specifically which training modality would result in largest improvements in arm function and activities after robot-mediated upper limb training after stroke.

Conclusions

Our review shows that most of the literature about robot-mediated therapy for stroke survivors refers to subjects in chronic phase. In the same way, training most frequently targeted the proximal arm.

Regarding the human-robot interaction, there has been poor attention in documenting the control strategy and identifying which strategy provides better results. This is hampered by the ambiguity in definitions of HRI method employed. While each robot would incorporate a lower-level control, interaction between robot and human is often made possible by incorporating an interaction modality, which is not standardised across different studies.

Therefore, we have proposed a categorisation of training modalities (Table 1) and features of human-robot interaction (Table 2) as an open framework to allow groups to identify the type of mechanism used in their studies, allowing better comparison of results for particular training modalities.

Even though only limited studies specifically investigated different control strategies, the present review indicates that robot-therapy in active assisted mode was highly predominant in the available studies and was associated with consistent improvements in arm function. More specifically, the use of HRI features stressing active contribution by the patient (e.g. EMG-modulated control, or a pushing force in combination with spring-damper guidance) in robot-mediated upper limb training after stroke may be beneficial. More research into comparing separate training modalities is needed to identify which specific training modality is associated with best improvements in arm function and activities after robot-mediated upper limb training after stroke.

References

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012, 125 (1): e2-e220.

Heuschmann PU, Di Carlo A, Bejot Y, Rastenyte D, Ryglewicz D, Sarti C, Torrent M, Wolfe CD: Incidence of stroke in Europe at the beginning of the 21st century. Stroke. 2009, 40 (5): 1557-1563.

Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, Finkelstein EA, Hong Y, Johnston SC, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Nelson SA, Nichol G, Orenstein D, Wilson PW, Woo YJ: Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011, 123 (8): 933-944. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5.

Kelly-Hayes M, Robertson JT, Broderick JP, Duncan PW, Hershey LA, Roth EJ, Thies WH, Trombly CA: The American Heart Association Stroke Outcome Classification. Stroke. 1998, 29 (6): 1274-1280. 10.1161/01.STR.29.6.1274.

Wolfe CD: The impact of stroke. Br Med Bull. 2000, 56 (2): 275-286.

Teasell R: Musculoskeletal complications of hemiplegia following stroke. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1991, 20 (6): 385-395. 10.1016/0049-0172(91)90014-Q.

Trombly CA: Deficits of reaching in subjects with left hemiparesis: a pilot study. Am J Occup Ther. 1992, 46 (10): 887-897. 10.5014/ajot.46.10.887.

Twitchell TE: The restoration of motor function following hemiplegia in man. Brain. 1951, 74 (4): 443-480. 10.1093/brain/74.4.443.

Brunnström S: Movement Therapy in Hemiplegia: A Neurophysiological Approach. 1970, New York: Medical Dept., Harper & Row

Chen R, Cohen LG, Hallett M: Nervous system reorganization following injury. Neuroscience. 2002, 111 (4): 761-773. 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00025-8.

Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH: Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice. 2007, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 3

Kwakkel G, Kollen B, Lindeman E: Understanding the pattern of functional recovery after stroke: facts and theories. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004, 22 (3–5): 281-299.

Cirstea MC, Levin MF: Compensatory strategies for reaching in stroke. Brain. 2000, 123 (Pt 5): 940-953.

Lennon S, Baxter D, Ashburn A: Physiotherapy based on the Bobath concept in stroke rehabilitation: a survey within the UK. Disabil. Rehabil. 2001, 23 (6): 254-262. 10.1080/096382801750110892.

Pollock A, Baer G, Langhorne P, Pomeroy V: Physiotherapy treatment approaches for the recovery of postural control and lower limb function following stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2007, 21 (5): 395-410. 10.1177/0269215507073438.

van Peppen RPS, Kwakkel G, der Wel BCH-v, Kollen BJ, Hobbelen JSM, Buurke JH, Halfens J, Wagenborg L, Vogel MJ, Berns M, van Klaveren R, Hendriks HJM, Dekker J: Guideline for stroke by KNGF [in Dutch: KNGF-richtlijn Beroerte]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Fysiotherapie. 2004, 114 (5 Suppl): 1-78.

Carr JH, Shepherd RB: A motor relearning programme for stroke. 1987, Rockville, MD: Aspen Publishers, 2

Liao JY, Kirsch RF: Predicting the initiation of minimum-jerk submovements in three-dimensional target-oriented human arm trajectories. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012, 2012: 6797-6800.

Langhorne P, Coupar F, Pollock A: Motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8 (8): 741-754. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70150-4.

Schaechter JD: Motor rehabilitation and brain plasticity after hemiparetic stroke. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004, 73 (1): 61-72. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.04.001.

Krakauer JW: Arm function after stroke: from physiology to recovery. Semin Neurol. 2005, 25 (4): 384-395. 10.1055/s-2005-923533.

Kwakkel G: Intensity of practice after stroke: More is better. Power. 2009, 7: 24-

Kwakkel G, van Peppen R, Wagenaar RC, Wood Dauphinee S, Richards C, Ashburn A, Miller K, Lincoln N, Partridge C, Wellwood I, Langhorne P: Effects of augmented exercise therapy time after stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2004, 35 (11): 2529-2539. 10.1161/01.STR.0000143153.76460.7d.

Mehrholz J, Hadrich A, Platz T, Kugler J, Pohl M: Electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training for improving generic activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 6: CD006876

Prange GB, Jannink MJ, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, Hermens HJ, Ijzerman MJ: Systematic review of the effect of robot-aided therapy on recovery of the hemiparetic arm after stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006, 43 (2): 171-184. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.04.0076.

Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, Krebs HI: Effects of robot-assisted therapy on upper limb recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008, 22 (2): 111-121.

Lo AC, Guarino PD, Richards LG, Haselkorn JK, Wittenberg GF, Federman DG, Ringer RJ, Wagner TH, Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Bever CT, Bravata DM, Duncan PW, Corn BH, Maffucci AD, Nadeau SE, Conroy SS, Powell JM, Huang GD, Peduzzi P: Robot-assisted therapy for long-term upper-limb impairment after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2010, 362 (19): 1772-1783. 10.1056/NEJMoa0911341.

Oujamaa L, Relave I, Froger J, Mottet D, Pelissier JY: Rehabilitation of arm function after stroke. Literature review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2009, 52 (3): 269-293. 10.1016/j.rehab.2008.10.003.

Timmermans AA, Seelen HA, Willmann RD, Kingma H: Technology-assisted training of arm-hand skills in stroke: concepts on reacquisition of motor control and therapist guidelines for rehabilitation technology design. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009, 6: 1-10.1186/1743-0003-6-1.

Brochard S, Robertson J, Medee B, Remy-Neris O: What's new in new technologies for upper extremity rehabilitation?. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010, 23 (6): 683-687. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833f61ce.

Huang VS, Krakauer JW: Robotic neurorehabilitation: a computational motor learning perspective. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009, 6: 5-10.1186/1743-0003-6-5.

Waldner A, Tomelleri C, Hesse S: Transfer of scientific concepts to clinical practice: recent robot-assisted training studies. Funct Neurol. 2009, 24 (4): 173-177.

Pignolo L: Robotics in neuro-rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2009, 41 (12): 955-960. 10.2340/16501977-0434.

Marchal-Crespo L, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Review of control strategies for robotic movement training after neurologic injury. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2009, 6: 20-10.1186/1743-0003-6-20.

Loureiro RC, Harwin WS, Nagai K, Johnson M: Advances in upper limb stroke rehabilitation: a technology push. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2011, 49 (10): 1103-1118. 10.1007/s11517-011-0797-0.

Balasubramanian S, Klein J, Burdet E: Robot-assisted rehabilitation of hand function. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010, 23 (6): 661-670. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833e99a4.

Peter O, Fazekas G, Zsiga K, Denes Z: Robot-mediated upper limb physiotherapy: review and recommendations for future clinical trials. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011, 34 (3): 196-202. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328346e8ad.

WHO: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2001, Geneva: WHO

Sivan M, O'Connor RJ, Makower S, Levesley M, Bhakta B: Systematic review of outcome measures used in the evaluation of robot-assisted upper limb exercise in stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2011, 43 (3): 181-189. 10.2340/16501977-0674.

Salter K, Jutai JW, Teasell R, Foley NC, Bitensky J: Issues for selection of outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation: ICF Body Functions. Disabil Rehabil. 2005, 27 (4): 191-207. 10.1080/09638280400008537.

Salter K, Jutai JW, Teasell R, Foley NC, Bitensky J, Bayley M: Issues for selection of outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation: ICF activity. Disabil Rehabil. 2005, 27 (6): 315-340. 10.1080/09638280400008545.

Salter K, Jutai JW, Teasell R, Foley NC, Bitensky J, Bayley M: Issues for selection of outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation: ICF Participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2005, 27 (9): 507-528. 10.1080/0963828040008552.

Fasoli SE, Krebs HI, Ferraro M, Hogan N, Volpe BT: Does shorter rehabilitation limit potential recovery poststroke?. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2004, 18 (2): 88-94. 10.1177/0888439004267434.

Duret C, Hutin E: Effects of prolonged robot-assisted training on upper limb motor recovery in subacute stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013, 33 (1): 41-48.

Aisen ML, Krebs HI, Hogan N, McDowell F, Volpe BT: The effect of robot-assisted therapy and rehabilitative training on motor recovery following stroke. Arch Neurol. 1997, 54 (4): 443-446. 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160075019.

Volpe BT, Krebs HI, Hogan N, Edelstein OL, Diels C, Aisen M: A novel approach to stroke rehabilitation: robot-aided sensorimotor stimulation. Neurology. 2000, 54 (10): 1938-1944. 10.1212/WNL.54.10.1938.

Rabadi M, Galgano M, Lynch D, Akerman M, Lesser M, Volpe B: A pilot study of activity-based therapy in the arm motor recovery post stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2008, 22 (12): 1071-1082. 10.1177/0269215508095358.

Dipietro L, Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Stein J, Bever C, Mernoff ST, Fasoli SE, Hogan N: Learning, not adaptation, characterizes stroke motor recovery: evidence from kinematic changes induced by robot-assisted therapy in trained and untrained task in the same workspace. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2012, 20 (1): 48-57.

Krebs HI, Mernoff S, Fasoli SE, Hughes R, Stein J, Hogan N: A comparison of functional and impairment-based robotic training in severe to moderate chronic stroke: a pilot study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008, 23 (1): 81-87.

Krebs HI, Ferraro M, Buerger SP, Newbery MJ, Makiyama A, Sandmann M, Lynch D, Volpe BT, Hogan N: Rehabilitation robotics: pilot trial of a spatial extension for MIT-Manus. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2004, 1 (1): 5-10.1186/1743-0003-1-5.

Stein J, Krebs HI, Frontera WR, Fasoli SE, Hughes R, Hogan N: Comparison of two techniques of robot-aided upper limb exercise training after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004, 83 (9): 720-728. 10.1097/01.PHM.0000137313.14480.CE.

Ferraro M, Palazzolo JJ, Krol J, Krebs HI, Hogan N, Volpe BT: Robot-aided sensorimotor arm training improves outcome in patients with chronic stroke. Neurology. 2003, 61 (11): 1604-1607. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000095963.00970.68.

Daly JJ, Hogan N, Perepezko EM, Krebs HI, Rogers JM, Goyal KS, Dohring ME, Fredrickson E, Nethery J, Ruff RL: Response to upper-limb robotics and functional neuromuscular stimulation following stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005, 42 (6): 723-736. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.02.0048.

Macclellan LR, Bradham DD, Whitall J, Volpe B, Wilson PD, Ohlhoff J, Meister C, Hogan N, Krebs HI, Bever CT: Robotic upper-limb neurorehabilitation in chronic stroke patients. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005, 42 (6): 717-722. 10.1682/JRRD.2004.06.0068.

Finley MA, Fasoli SE, Dipietro L, Ohlhoff J, Macclellan L, Meister C, Whitall J, Macko R, Bever CT, Krebs HI, Hogan N: Short-duration robotic therapy in stroke patients with severe upper-limb motor impairment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005, 42 (5): 683-692. 10.1682/JRRD.2004.12.0153.

Volpe BT, Lynch D, Rykman-Berland A, Ferraro M, Galgano M, Hogan N, Krebs HI: Intensive sensorimotor arm training mediated by therapist or robot improves hemiparesis in patients with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008, 22 (3): 305-310. 10.1177/1545968307311102.

Posteraro F, Mazzoleni S, Aliboni S, Cesqui B, Battaglia A, Carrozza MC, Dario P, Micera S: Upper limb spasticity reduction following active training: a robot-mediated study in patients with chronic hemiparesis. J Rehabil Med. 2010, 42 (3): 279-281. 10.2340/16501977-0500.

Conroy SS, Whitall J, Dipietro L, Jones-Lush LM, Zhan M, Finley MA, Wittenberg GF, Krebs HI, Bever CT: Effect of gravity on robot-assisted motor training after chronic stroke: a randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011, 92 (11): 1754-1761. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.06.016.

Mazzoleni S, Sale P, Franceschini M, Bigazzi S, Carrozza MC, Dario P, Posteraro F: Effects of proximal and distal robot-assisted upper limb rehabilitation on chronic stroke recovery. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013, 33 (1): 33-39.

Zollo L, Rossini L, Bravi M, Magrone G, Sterzi S, Guglielmelli E: Quantitative evaluation of upper-limb motor control in robot-aided rehabilitation. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2011, 49 (10): 1131-1144. 10.1007/s11517-011-0808-1.

Pellegrino G, Tomasevic L, Tombini M, Assenza G, Bravi M, Sterzi S, Giacobbe V, Zollo L, Guglielmelli E, Cavallo G, Vernieri F, Tecchio F: Inter-hemispheric coupling changes associate with motor improvements after robotic stroke rehabilitation. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2012, 30 (6): 497-510.

Hesse S, Waldner A, Mehrholz J, Tomelleri C, Pohl M, Werner C: Combined transcranial direct current stimulation and robot-assisted arm training in subacute stroke patients: an exploratory, randomized multicenter trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011, 25 (9): 838-846. 10.1177/1545968311413906.

Hesse S, Werner C, Pohl M, Rueckriem S, Mehrholz J, Lingnau ML: Computerized arm training improves the motor control of the severely affected arm after stroke: a single-blinded randomized trial in two centers. Stroke. 2005, 36 (9): 1960-1966. 10.1161/01.STR.0000177865.37334.ce.

Hsieh YW, Wu CY, Liao WW, Lin KC, Wu KY, Lee CY: Effects of treatment intensity in upper limb robot-assisted therapy for chronic stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011, 25 (6): 503-511. 10.1177/1545968310394871.

Hesse S, Schulte-Tigges G, Konrad M, Bardeleben A, Werner C: Robot-assisted arm trainer for the passive and active practice of bilateral forearm and wrist movements in hemiparetic subjects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003, 84 (6): 915-920. 10.1016/S0003-9993(02)04954-7.

Liao WW, Wu CY, Hsieh YW, Lin KC, Chang WY: Effects of robot-assisted upper limb rehabilitation on daily function and real-world arm activity in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2012, 26 (2): 111-120. 10.1177/0269215511416383.

Wu CY, Yang CL, Chuang LL, Lin KC, Chen HC, Chen MD, Huang WC: Effect of therapist-based versus robot-assisted bilateral arm training on motor control, functional performance, and quality of life after chronic stroke: a clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2012, 92 (8): 1006-1016. 10.2522/ptj.20110282.

Burgar CG, Lum PS, Scremin AM, Garber SL, Van der Loos HF, Kenney D, Shor P: Robot-assisted upper-limb therapy in acute rehabilitation setting following stroke: Department of Veterans Affairs multisite clinical trial. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011, 48 (4): 445-458. 10.1682/JRRD.2010.04.0062.

Lum PS, Burgar CG, Van der Loos M, Shor PC, Majmundar M, Yap R: MIME robotic device for upper-limb neurorehabilitation in subacute stroke subjects: A follow-up study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006, 43 (5): 631-642. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.02.0044.

Burgar CG, Lum PS, Shor PC, Van der Loos HFM: Development of robots for rehabilitation therapy: the Palo Alto VA/Stanford experience. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000, 37 (6): 663-673.

Lum PS, Burgar CG, Shor PC, Majmundar M, Van der Loos M: Robot-assisted movement training compared with conventional therapy techniques for the rehabilitation of upper-limb motor function after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002, 83 (7): 952-959. 10.1053/apmr.2001.33101.

Lum PS, Burgar CG, Shor PC: Evidence for improved muscle activation patterns after retraining of reaching movements with the MIME robotic system in subjects with post-stroke hemiparesis. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2004, 12 (2): 186-194. 10.1109/TNSRE.2004.827225.

Colombo R, Pisano F, Mazzone A, Delconte C, Micera S, Carrozza MC, Dario P, Minuco G: Design strategies to improve patient motivation during robot-aided rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2007, 4: 3-10.1186/1743-0003-4-3.

Squeri V, Masia L, Giannoni P, Sandini G, Morasso P: Wrist rehabilitation in chronic stroke patients by means of adaptive, progressive robot-aided therapy. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2014, 22 (2): 312-325.

Abdullah HA, Tarry C, Lambert C, Barreca S, Allen BO: Results of clinicians using a therapeutic robotic system in an inpatient stroke rehabilitation unit. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011, 8: 50-10.1186/1743-0003-8-50.

Pinter D, Pegritz S, Pargfrieder C, Reiter G, Wurm W, Gattringer T, Linderl-Madrutter R, Neuper C, Fazekas F, Grieshofer P, Enzinger C: Exploratory study on the effects of a robotic hand rehabilitation device on changes in grip strength and brain activity after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2013, 20 (4): 308-316. 10.1310/tsr2004-308.

Sale P, Lombardi V, Franceschini M: Hand robotics rehabilitation: feasibility and preliminary results of a robotic treatment in patients with hemiparesis. Stroke Res Treat. 2012, 2012: 820931-

Stein J, Bishop L, Gillen G, Helbok R: Robot-assisted exercise for hand weakness after stroke: a pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011, 90 (11): 887-894.

Hwang CH, Seong JW, Son DS: Individual finger synchronized robot-assisted hand rehabilitation in subacute to chronic stroke: a prospective randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Clin Rehabil. 2012, 26 (8): 696-704. 10.1177/0269215511431473.

Ellis MD, Sukal-Moulton T, Dewald JP: Progressive shoulder abduction loading is a crucial element of arm rehabilitation in chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009, 23 (8): 862-869. 10.1177/1545968309332927.

Kahn LE, Zygman ML, Rymer WZ, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Robot-assisted reaching exercise promotes arm movement recovery in chronic hemiparetic stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2006, 3: 12-10.1186/1743-0003-3-12.

Cordo P, Lutsep H, Cordo L, Wright WG, Cacciatore T, Skoss R: Assisted movement with enhanced sensation (AMES): coupling motor and sensory to remediate motor deficits in chronic stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009, 23 (1): 67-77.

Chang JJ, Tung WL, Wu WL, Huang MH, Su FC: Effects of robot-aided bilateral force-induced isokinetic arm training combined with conventional rehabilitation on arm motor function in patients with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007, 88 (10): 1332-1338. 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.016.

Merians AS, Fluet GG, Qiu Q, Saleh S, Lafond I, Davidow A, Adamovich SV: Robotically facilitated virtual rehabilitation of arm transport integrated with finger movement in persons with hemiparesis. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011, 8: 27-10.1186/1743-0003-8-27.

Wei XJ, Tong KY, Hu XL: The responsiveness and correlation between Fugl-Meyer Assessment, Motor Status Scale, and the Action Research Arm Test in chronic stroke with upper-extremity rehabilitation robotic training. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011, 34 (4): 349-356. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32834d330a.

Hu X, Tong KY, Song R, Tsang VS, Leung PO, Li L: Variation of muscle coactivation patterns in chronic stroke during robot-assisted elbow training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007, 88 (8): 1022-1029. 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.006.

Song R, Tong KY, Hu X, Zhou W: Myoelectrically controlled wrist robot for stroke rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2013, 10: 52-10.1186/1743-0003-10-52.

Hu XL, Tong KY, Song R, Zheng XJ, Lui KH, Leung WW, Ng S, Au-Yeung SS: Quantitative evaluation of motor functional recovery process in chronic stroke patients during robot-assisted wrist training. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009, 19 (4): 639-650. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.04.002.

Hu XL, Tong KY, Li R, Xue JJ, Ho SK, Chen P: The effects of electromechanical wrist robot assistive system with neuromuscular electrical stimulation for stroke rehabilitation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012, 22 (3): 431-439. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.12.010.

Stein J, Narendran K, McBean J, Krebs K, Hughes R: Electromyography-controlled exoskeletal upper-limb-powered orthosis for exercise training after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007, 86 (4): 255-261. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3180383cc5.

Kutner NG, Zhang R, Butler AJ, Wolf SL, Alberts JL: Quality-of-life change associated with robotic-assisted therapy to improve hand motor function in patients with subacute stroke: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2010, 90 (4): 493-504. 10.2522/ptj.20090160.

Song R, Tong KY, Hu X, Li L: Assistive control system using continuous myoelectric signal in robot-aided arm training for patients after stroke. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2008, 16 (4): 371-379.

Song R, Tong KY, Hu X, Li L, Sun R: Arm-eye coordination test to objectively quantify motor performance and muscles activation in persons after stroke undergoing robot-aided rehabilitation training: a pilot study. Exp Brain Res. 2013, 229 (3): 373-382. 10.1007/s00221-013-3418-3.

Amirabdollahian F, Loureiro R, Gradwell E, Collin C, Harwin W, Johnson G: Multivariate analysis of the Fugl-Meyer outcome measures assessing the effectiveness of GENTLE/S robot-mediated stroke therapy. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2007, 4: 4-10.1186/1743-0003-4-4.

Lambercy O, Dovat L, Yun H, Wee SK, Kuah CW, Chua KS, Gassert R, Milner TE, Teo CL, Burdet E: Effects of a robot-assisted training of grasp and pronation/supination in chronic stroke: a pilot study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011, 8: 63-

Takahashi CD, Der-Yeghiaian L, Le V, Motiwala RR, Cramer SC: Robot-based hand motor therapy after stroke. Brain. 2008, 131 (Pt 2): 425-437.

Riley JD, Le V, Der-Yeghiaian L, See J, Newton JM, Ward NS, Cramer SC: Anatomy of stroke injury predicts gains from therapy. Stroke. 2011, 42 (2): 421-426. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599340.

Casadio M, Giannoni P, Morasso P, Sanguineti V: A proof of concept study for the integration of robot therapy with physiotherapy in the treatment of stroke patients. Clin Rehabil. 2009, 23 (3): 217-228. 10.1177/0269215508096759.

Colombo R, Pisano F, Micera S, Mazzone A, Delconte C, Carrozza MC, Dario P, Minuco G: Assessing mechanisms of recovery during robot-aided neurorehabilitation of the upper limb. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008, 22 (1): 50-63.

Colombo R, Sterpi I, Mazzone A, Delconte C, Minuco G, Pisano F: Measuring changes of movement dynamics during robot-aided neurorehabilitation of stroke patients. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2010, 18 (1): 75-85.

Panarese A, Colombo R, Sterpi I, Pisano F, Micera S: Tracking motor improvement at the subtask level during robot-aided neurorehabilitation of stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012, 26 (7): 822-833. 10.1177/1545968311431966.

Colombo R, Sterpi I, Mazzone A, Delconte C, Pisano F: Robot-aided neurorehabilitation in sub-acute and chronic stroke: does spontaneous recovery have a limited impact on outcome?. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013, 33 (4): 621-629.

Fazekas G, Horvath M, Troznai T, Toth A: Robot-mediated upper limb physiotherapy for patients with spastic hemiparesis: a preliminary study. J Rehabil Med. 2007, 39 (7): 580-582. 10.2340/16501977-0087.

Masiero S, Armani M, Rosati G: Upper-limb robot-assisted therapy in rehabilitation of acute stroke patients: focused review and results of new randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011, 48 (4): 355-366. 10.1682/JRRD.2010.04.0063.

Masiero S, Celia A, Rosati G, Armani M: Robotic-assisted rehabilitation of the upper limb after acute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007, 88 (2): 142-149. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.032.

Treger I, Faran S, Ring H: Robot-assisted therapy for neuromuscular training of sub-acute stroke patients. A feasibility study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008, 44 (4): 431-435.

Bovolenta F, Sale P, Dall'Armi V, Clerici P, Franceschini M: Robot-aided therapy for upper limbs in patients with stroke-related lesions. Brief report of a clinical experience. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011, 8: 18-

Housman SJ, Scott KM, Reinkensmeyer DJ: A randomized controlled trial of gravity-supported, computer-enhanced arm exercise for individuals with severe hemiparesis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009, 23 (5): 505-514. 10.1177/1545968308331148.

Sanchez RJ, Liu J, Rao S, Shah P, Smith R, Rahman T, Cramer SC, Bobrow JE, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Automating arm movement training following severe stroke: functional exercises with quantitative feedback in a gravity-reduced environment. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2006, 14 (3): 378-389.

Reinkensmeyer DJ, Wolbrecht ET, Chan V, Chou C, Cramer SC, Bobrow JE: Comparison of three-dimensional, assist-as-needed robotic arm/hand movement training provided with Pneu-WREX to conventional tabletop therapy after chronic stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012, 91 (11 Suppl 3): S232-S241.

Abdollahi F, Case Lazarro ED, Listenberger M, Kenyon RV, Kovic M, Bogey RA, Hedeker D, Jovanovic BD, Patton JL: Error augmentation enhancing arm recovery in individuals with chronic stroke: a randomized crossover design. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014, 28 (2): 120-128. 10.1177/1545968313498649.

Byl NN, Abrams GM, Pitsch E, Fedulow I, Kim H, Simkins M, Nagarajan S, Rosen J: Chronic stroke survivors achieve comparable outcomes following virtual task specific repetitive training guided by a wearable robotic orthosis (UL-EXO7) and actual task specific repetitive training guided by a physical therapist. J Hand Ther. 2013, 26 (4): 343-352. 10.1016/j.jht.2013.06.001.

Rabin BA, Burdea GC, Roll DT, Hundal JS, Damiani F, Pollack S: Integrative rehabilitation of elderly stroke survivors: the design and evaluation of the BrightArm. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012, 7 (4): 323-335. 10.3109/17483107.2011.629329.

Dohle CI, Rykman A, Chang J, Volpe BT: Pilot study of a robotic protocol to treat shoulder subluxation in patients with chronic stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2013, 10: 88-10.1186/1743-0003-10-88.

Frisoli A, Procopio C, Chisari C, Creatini I, Bonfiglio L, Bergamasco M, Rossi B, Carboncini MC: Positive effects of robotic exoskeleton training of upper limb reaching movements after stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012, 9: 36-10.1186/1743-0003-9-36.

Hu XL, Tong KY, Wei XJ, Rong W, Susanto EA, Ho SK: The effects of post-stroke upper-limb training with an electromyography (EMG)-driven hand robot. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013, 23 (5): 1065-1074. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2013.07.007.

Merians AS, Tunik E, Fluet GG, Qiu Q, Adamovich SV: Innovative approaches to the rehabilitation of upper extremity hemiparesis using virtual environments. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009, 45 (1): 123-133.

Emken JL, Benitez R, Sideris A, Bobrow JE, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Motor adaptation as a greedy optimization of error and effort. J Neurophysiol. 2007, 97 (6): 3997-4006. 10.1152/jn.01095.2006.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this manuscript was partially funded by the European project ‘SCRIPT’ Grant agreement no: 288698 (http://scriptproject.eu). SN has been hosted at University of Hertfordshire in a short-term scientific mission funded by the COST Action TD1006 European Network on Robotics for NeuroRehabilitation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

FA conceived of the idea to clarify the mechanism of interaction between human and robots. AB and SN contributed equally to data collection and analysis, and writing of the manuscript. AB and SN both reviewed all abstracts and full articles included in this review. AS, JB, GP and FA provided edits and revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12984_2013_634_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 2: ReviewedArticles.xlsx: an Excel spreadsheet which contains an entry for each of the groups, with all the aspects treated in this review (subjects group, arm segments, training modality and features of implementation and indicators for clinical outcome) and others as training duration, and the device used.(XLSX 48 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Basteris, A., Nijenhuis, S.M., Stienen, A.H. et al. Training modalities in robot-mediated upper limb rehabilitation in stroke: a framework for classification based on a systematic review. J NeuroEngineering Rehabil 11, 111 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-11-111

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-11-111