Abstract

Background

Many risk factors for fractures have been documented, including low bone-mineral density (BMD) and a history of fractures. However, little is known about the short-term absolute risk (AR) of fractures and the timing of clinical fractures. Therefore, we assessed the risk and timing of incident clinical fractures, expressed as 5-year AR, in postmenopausal women.

Methods

In total, 10 general practice centres participated in this population-based prospective study. Five years after a baseline assessment, which included clinical risk factor evaluation and BMD measurement, 759 postmenopausal women aged between 50 and 80 years, were re-examined, including undergoing an evaluation of clinical fractures after menopause. Risk factors for incident fractures at baseline that were significant in univariate analyses were included in a multivariate Cox survival regression analysis. The significant determinants were used to construct algorithms.

Results

In the total group, 12.5% (95% confidence interval (CI) 10.1–14.9) of the women experienced a new clinical fracture. A previous clinical fracture after menopause and a low BMD (T-score <-1.0) were retained as significant predictors with significant interaction. Women with a recent previous fracture (during the past 5 years) had an AR of 50.1% (95% CI 42.0–58.1) versus 21.2% (95% CI 20.7–21.6) if the previous fracture had occurred earlier. In women without a fracture history, the AR was 13.8% (95% CI 10.9–16.6) if BMD was low and 7.0% (95% CI 5.5–8.5) if BMD was normal.

Conclusion

In postmenopausal women, clinical fractures cluster in time. One in two women with a recent clinical fracture had a new clinical fracture within 5 years, regardless of BMD. The 5-year AR for a first clinical fracture was much lower and depended on BMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), osteoporosis is the second leading health problem in the developed world in terms of numbers [1, 2], owing to the ageing of the western female population [1–9]. The incidence of fractures is related to the age of the population, and to skeletal and extra-skeletal factors [1–9]. The worldwide lifetime risk of osteoporotic fractures in women is 40%, and because of the ageing of the population, the overall prevalence of osteoporotic fractures is expected to rise considerably [10]. The mortality rate for hip fractures varies between 15 and 30% [10–12]. In 1990, there were 1.7 million hip fractures worldwide, and this could increase to 6.3 million by 2050 [10]. The resulting hospital costs alone amount to over US$3976 million in the European Union, US$500 million in Australia, US$5700 million in the USA, and US$9359 million in Japan [10]. In view of this high morbidity, mortality and economic burden, it is important to identify those groups of patients who are at high risk and for whom interventions to prevent osteoporotic fractures would be most effective [3, 4, 6–9].

In 1992–1994, a cross-sectional population-based study assessed BMD and other determinants that might influence osteoporosis among 4203 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 80 [7–9]. A random sample of women from the above study was re-examined 5–6 years later, allowing us to study the prognostic value of relevant determinants of experiencing a fracture.

Several researchers have addressed the same subject [13–22], and the WHO is currently developing a fracture risk assessment tool with which family physicians can predict 5-year and 10-year fracture risk [23]. However, data are scarce about the absolute risk (AR) of fractures and the timing of a previous clinical fracture [14–16]. Available studies suggest that fracture risk is highest immediately after a fracture, with the risk of an osteoporotic fracture being 12.0%[14] and that of any fracture being 12.2% during the first 2 years[16]. The risk of morphological vertebral fractures is 19.2% at 1 year after a previous morphological vertebral fracture[15]. The goal of our study was to assess the 5-year AR of incident clinical fractures among postmenopausal women.

Methods

Ethics

The ethics review committee of the Maastricht University and the Maastricht University Hospital approved the study (reference number MEC 94-196.1).

Participants

In total, 20 general practitioners (GPs) from 10 general practice centres participated. The participating general practices were invited based on their familiarity with the rules of 'good clinical practice' and based on their participation in earlier studies. The region can best be described as consisting of two cities surrounded by suburban villages [7].

A random sample of 1686 postmenopausal women, aged between 50 and 80 years, was drawn from the above study population [7–9]. Participating women signed an informed consent form.

Measurements

The assessments in 1992–1994 started with weight (in kilograms), height (in centimetres), and BMD (measured by a computer-guided DXA instrument; Hologic QDR-1000, Hologic Europe, Brussels, Belgium). Four experienced and specially trained research nurses performed all the measurements. After the measurements, the participants completed a questionnaire, which concentrated on variables possibly related to osteoporosis or low BMD [7–9]. In addition, all women were questioned about their medical history (including fracture history), family history and diet [7].

In the 1998–2000 assessments, one specially trained research nurse, or the principal investigator, completed a questionnaire in the presence of the participant, which recorded the history of fractures. The research assistant confirmed all fractures reported by the patients by searching the medical files in the participating GP centres. In the Netherlands, clinical fractures are treated in hospital and then reported to the patient's GP, who always includes this information in the patient's medical file. In our study, every fracture reported by a patient could thus be confirmed by her medical file.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 11.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The dependent variable was the first fracture suffered by a woman after baseline, taking only the first fracture after menopause into account. A power calculation for our main variable (timing of a previous fracture) was performed. This calculation compared two proportions [24].

The hazard of first fracture and the death hazard were used to compute the 5-year probability of fractures. Univariate Cox regression analysis was used to analyse possible predictors of suffering a fracture. Before being entered into the regression analysis, the non-discrete variables were dichotomised at the mean. The cutoff points for coffee intake per day and alcohol intake per week were set at five or more consumptions. The variables 'smoking' and 'sports', both past and present, were dichotomised as yes/no. The resulting significant variables were entered into a multivariate Cox regression to calculate the 5-year probability of fracture.

Further analysis investigated the influence of timing of a previous clinical fracture. A discrete variable was used, categorised as participants with a recent previous fracture (in the past 5 years; n = 68) and participants with an older previous fracture (longer than 5 years previously, but still after menopause; n = 62). The 5-year cutoff point was the optimum compromise between finding a sufficient number of fractures to allow statistical evaluation and minimising the loss to recall [7]. Thereafter, a multivariate subgroup analysis was performed, including the timing of previous fractures. These significant determinants were used to construct algorithms, which included relative risk (RR), AR and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

At baseline (1992–1994), BMD values for lumbar spine were divided into two categories: BMD T-score <-1.0 (including osteoporosis plus osteopenia) and T-score ≥ -1.0, according to WHO criteria [1].

Results

Of the 1686 women, 1207 were traceable and alive, and 759 agreed to take part in the follow-up measurement. This corresponded to a response rate of 62.9% of the traceable and surviving women (Figure 1). Non-participating women were compared with participating women in terms of the baseline variables. Age was the only variable that differed between the responders and non-responders; non-participants were on average 3.5 years older than participants.

The power calculation compares a recent previous fracture (n = 68) versus an older previous fracture (n = 62). The two proportions were 0.50 (34/68) and 0.19 (12/62), which resulted in a two-sided power of 0.95. This result showed that the study was sufficiently powered.

The characteristics of the study population at baseline (1992–1994) are shown in Tables 1 (non-discrete variables) and 2 (discrete variables). In total, 95 women (12.5%; 95% CI 10.1–14.9) had a clinical fracture during the 5-year follow-up (Table 3).

The univariate Cox regression showed that low BMD (T < -1.0), increasing age, a history of clinical fracture after menopause, coffee intake, and current or past smoking were significant predictors of a new clinical fracture (Table 4).

As shown in Table 1, there seemed to be some very low values for calcium intake. In an extended univariate Cox regression analysis to investigate the influence of this factor, the lowest quintile and quartile of calcium intake were excluded. This exclusion did not change the results [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.4, 95% CI 0.9–2.2, and HR = 1.3, 95% CI 0.8–2.0, respectively].

These significant determinants were entered into a multivariate Cox regression. The results of this analysis showed that a previous fracture (HR = 5.0, 95% CI 3.4–7.5) was a significant risk factor, and an interaction was found between a previous fracture and BMD. Low BMD contributed significantly only in the presence of interaction, and was therefore an effect modifier. Low BMD was not a significant predictor for patients with a previous fracture (n = 130; HR = 1.5, 95% CI 0.8–2.9), but was for those without (n = 629; HR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.5–5.8).

Table 3shows the details of 31 hand, foot and other fractures stated. Of these 31 fractures, 12 were caused by a traumatic accident (for example, fall from stairs or bicycle, or fractures incurred during sports). We therefore excluded these 12 fractures from an extended analysis. Multivariate Cox regression again showed that a previous fracture (HR = 5.0, 95% CI 3.2–7.8) was the most significant risk factor. Furthermore, low BMD contributed significantly only in the presence of an interaction, and was a significant predictor only for those without a previous fracture (n = 629; HR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.2–5.0). Thus, we found that excluding the fractures caused by a trauma did not change the results and they were therefore not excluded from further analysis.

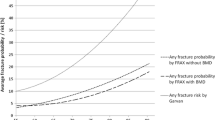

The multivariate subgroup analysis, including the timing of a previous fracture, showed that a recent previous fracture contributed significantly more to the risk of a new clinical fracture than did an older previous fracture (HR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7–6.3). Thus, whether a previous fracture was recent was an important risk factor for suffering a new clinical fracture. This result is illustrated in the cumulative survival plot of the postmenopausal women with a previous fracture (Figure 2), and shows clearly that a recent previous fracture was a much more important risk factor than an older previous fracture (R2 = 0.98 for an exponential trend line and 0.76 for a linear trend line).

The AR for incident clinical fracture was 50.1% (95% CI 42.0–58.1) in women with a recent previous fracture, and 21.2% (95% CI 20.7–21.6) in women with an older previous fracture (Figure 3). In women without a fracture history after menopause, BMD was a significant predictor. The participants without a fracture history and with normal BMD (T ≥ -1.0) had an AR of 7.0% (95% CI 5.5–8.5). This risk was 44.0% lower than that in the total study population (12.5%), and this subgroup represented 35.0% of the total study population. Women without a previous fracture and with low BMD had an AR of 13.8% (95% CI 10.9–16.6), which was 10.4% higher than that of the total study population (Figure 3).

Algorithm of risk factors for a new clinical fracture. Algorithm of risk factors for a new clinical fracture, their absolute risks (AR) plus 95% confidence intervals (CI), and relative risks (RR) for the subgroup with (n = 130) and without (n = 629) a fracture history. * Significant risk factors for a new clinical fracture based on multivariate Cox survival analysis; **reference.

Discussion

The results show that clinical fractures in postmenopausal women cluster in time. One in two women with a recent previous clinical fracture had a new clinical fracture within 5 years, regardless of BMD. The 5-year AR for a first clinical fracture was much lower and depended on BMD.

The HR of a previous fracture (5.0) is higher than the 2.0 reported in a large meta-analysis[5]; however, our analysis showed that having an older previous fracture (n = 62) led to an HR of 2.5 (95% CI 1.3–4.8), which is closer to the reported AR. The results show that a recent previous fracture is a more important predictor of a new clinical fracture than is an older previous fracture. Owing to effect modification, the algorithm differs between the subgroups with and without a previous fracture, leading to a stronger prediction model per subgroup. This allowed a low-risk group (35.0%) to be identified, consisting of women who can be spared a great deal of unnecessary worry. Nevertheless, 17.2% of the population were at very high risk.

The incidence of vertebral fractures may have been underestimated in our study because only clinical fractures were used. Morphometric fractures that do not come to clinical attention have significance and are not without symptoms[25, 26]. Kanis et al[27] showed that the 10-year vertebral probability of morphometric fractures was higher than for clinical fractures alone. Furthermore, morphometric fractures increase the risk of a new clinical fracture significantly and are, therefore, of prognostic significance[15]. BMD, especially measured at the spine, is a strong predictor of a first vertebral fracture[28]. All women in our study with a clinical vertebral fracture (n = 7) had a low BMD. Thus, our AR is generally an underestimate compared with the AR of fractures found when all morphometric fractures were taken into account.

The factors that were independent and significant predictors of fracture risk in our study have been investigated previously, leading to partly comparable results. However, limited data are available about absolute fracture risk and the timing of a previous clinical fracture [14–16] when controlling for most other risk factors. Our study differs from previous in some methodological aspects. Firstly, some studies used prospective data, but presented a risk prediction tool for 1 year[14–16, 22, 29], which could be too short a time span. Secondly, many studies developed a prediction model specially for hip or vertebral fractures [13, 15, 17–20], while we included all fractures. Finally, previous results may have differed from ours in terms of geographical factors. For example, the participants of the Dubbo Osteoporosis Study [20] lived in a region with considerably more sun shine than in northern Europe [30, 31], which might result in different vitamin D levels.

Age has been documented as a risk factor for fractures in several studies. In our study, age was a significant risk factor for a new clinical fracture only in the univariate analysis. One reason could be that we studied a relatively young population compared with other prospective studies, and the timing of a previous fracture is the main risk for new fractures for this population. All women were aged 50–80 years, with only 12.0% of the population aged 70 years and over, whereas women included in other studies were aged 65 years and over [19–21]. It is possible that our ARs are an underestimate, due to the 3.5-year age difference between the responders and non-responders. However, our results hardly differ from other studies, such as that of Johnell et al[32]. Based on person-years, our absolute fracture risk was 2.7% (95/3542), which is close to the AR reported by Johnell et al (AR: 2.2%; 3694/168 366)[32].

Our study was subject to some limitations. BMD measurement was performed on the lumbar spine, a measurement that can be influenced by osteoarthritis among the elderly. Measurements at the hip could have given additional information, but this had not been performed at baseline (1992–1994). Furthermore, 45 participants (5.9%) received advice about calcium intake and exercise after baseline measurements. Some participants may have heeded this advice, and may therefore have improved their lifestyle. However, the advice differed little from the recommendations regularly made to the general public, on which women may also act. One other factor that may have affected the results is the previous use of medication. However, only the 45 women mentioned above were being treated for osteoporosis (including treatment with a placebo), and excluding these participants from the analysis did not change the results. Finally, our sample size was relatively small in comparison with that in other studies. Johnell et al[32] studied 38 973 men and women (75% women) from 12 prospective cohorts. The total number of osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic fractures in these cohorts was 3694 (AR = 9.5%)[32]. This indicates that even though our sample was relatively small, our absolute fracture risk was still higher than the AR of Johnell's 12 prospective cohorts[32]. Based on person-years instead of numbers of participants, as mentioned previously, our absolute fracture risk was 2.7% (95/3542), which is close to the AR reported by Johnell et al (AR = 2.2%; 3694/168 366)[32].

Conclusion

The main conclusion of our study is that a recent previous fracture is a relevant factor in detecting postmenopausal women at high risk. One in two women with a recent previous fracture had a new clinical fracture within 5 years, regardless of BMD. This might be interesting information for a variety of professionals: GPs and hospital specialists can use it to quickly and accurately assess which postmenopausal women are at high or low risk, and thus, for which women fracture prevention should be initiated immediately. Future research should try to verify our results using a longer follow-up period.

References

Anonymous: Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994, 843: 1-129.

Hamblen D: Who cares for the patient with a fragility fracture?. Orthop Today Internat. 2004, 7: [http://www.boneandjointdecade.org/Default.aspx?contId=538]

Boereboom FTJ, de Groot RRM, Raymakers JA, Duursma SA: The incidence of hip fractures in The Netherlands. Neth J Med. 1991, 38: 51-58.

Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg CBO: Osteoporose Tweede Herziene Richtlijn. 2002, Alphen aan de Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications BV

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA, Berger ML: Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000, 15: 721-727. 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721.

Riggs BL, Melton LJ: The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone. 1995, 17: 505-511S. 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00258-4.

van der Voort DJM, Dinant GJ, Rinkens PELM, van der Voort-Duindam CJM, van Wersch JWJ, Geusens PP: Construction of an algorithm for quick detection of patients with low bone mineral density and its applicability in daily general practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000, 53: 1095-1103. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00226-2.

van der Voort DJM, Geusens PP, Dinant GJ: Risk factors for osteoporosis related to their outcome: fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12: 630-638. 10.1007/s001980170062.

van der Voort DJM, van der Weijer PHM, Barentsen R: Early menopause: Increased fracture risk at older age. Osteoporos Int. 2003, 14: 525-530. 10.1007/s00198-003-1408-1.

Delmas PD, Fraser M: Strong bones in later life: luxury or necessity?. Bull World Health Organ. 1999, 77: 416-422.

Browner WS, Pressman AR, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR: Mortality following fractures in older women. The study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 1996, 156: 1521-1525. 10.1001/archinte.156.14.1521.

Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA: Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. BMJ. 1993, 307: 1248-1250.

Burger H, De Laet CE, Weel AEAM, Hofman A, Pols HAP: Added value of bone mineral density in hip fracture risk scores. Bone. 1999, 25: 369-374. 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00173-8.

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, de Laet CEDH, Jonsson B: Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004, 15: 175-179. 10.1007/s00198-003-1514-0.

Lindsay RL, Silverman SL, Cooper C, Hanley DA, Barton I, Broy SB, Licata A, Benhamou L, Geusens P, Flowers K, et al: Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001, 285: 320-323. 10.1001/jama.285.3.320.

van Helden S, Cals J, Kessels F, Brink P, Dinant GJ, Geusens P: Risk of new clinical fractures within 2 years following a fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006, 17: 348-354. 10.1007/s00198-005-2026-x.

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, Cauley J, Black DM, Vogt TM: Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. N Engl J Med. 1995, 332: 767-773. 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202.

van der Klift M, de Laet CEDH, McCloskey EV, Johnell O, Kanis JA: Risk factors for incident vertebral fractures in men and women: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004, 19: 1172-1180. 10.1359/JBMR.040215.

McGrother CW, Donaldson MM, Clayton D, Abrams KR, Clarke M: Evaluation of a hip fracture risk score for assessing elderly women: the Melton Osteoporotic Fracture (MOF) study. Osteoporos Int. 2002, 13: 89-96. 10.1007/s198-002-8343-6.

Nguyen ND, Pongchaiyakul C, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV: Identification of high-risk individuals for hip fracture: a 14-year prospective study. J Bone Mineral Res. 2005, 20: 1921-1928. 10.1359/JBMR.050520.

Black DM, Steinbuch M, Palermo L, Dargent-Molina P, L LR, Hoseyni MS, Johnell O: An assessment tool for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12: 519-528. 10.1007/s001980170072.

Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E, Faulkner KG, Wehren LE, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM: Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA. 2001, 286: 2815-2822. 10.1001/jama.286.22.2815.

International Osteoporosis Foundation: WHO Working Group on Fracture Risk Assessment. [http://www.osteofound.org/activities/world_health_organization.html]

Java Applets for Power and Sample Size (computer software). [http://www.stat.uiowa.edu/~rlenth/Power]

Nevitt MC, Ettinger B, Black DM, Stone K, Jamal SA, Ensrud K, Segal M, Genant HK, Cummings SR: The association of radiographically detected vertebral fractures with back pain and function: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 128: 793-800.

Nevitt MC, Thompson DE, Black DM, Rubin SR, Ensrud K, Yates AJ, Cummings SR: Effect of alendronate on limited-activity days and bed-disability days caused by back pain in postmenopausal women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 77-85. 10.1001/archinte.160.1.77.

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, De Laet C, Jonsson B: The risk and burden of vertebral fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int. 2004, 15: 20-26. 10.1007/s00198-003-1463-7.

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Stone KL, Palermo L, Black DM, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Hochberg MC, Ensrud KE, Hillier TA, et al: Risk factors for a first-incident radiographic vertebral fracture in women ≥ 65 years of age: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20: 131-140. 10.1359/jbmr.2005.20.1.131.

Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, Abbott TA, Chen YT, Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES: An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2004, 164: 1113-1120. 10.1001/archinte.164.10.1113.

Climate Information Service NCC, Bureau of Meteorology: Mean hours of bright sunshine. Melbourne. 2004

Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut: Aantal uren zonneschijn. [http://www.knmi.nl/klimatologie/normalen1971-2000/per_station/stn380/4-normalen/380_maastricht.pdf]

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Delmas P, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, Mellstrom D, et al: Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Mineral Res. 2005, 20: 1185-1194. 10.1359/JBMR.050304.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/4/24/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to express appreciation to Mrs Pauline Versteeg, research assistant, who contributed substantially to the data acquisition. This project was supported by grants from Maastricht University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ACMG is the principal investigator and the main author of the manuscript. PPG and GJD are the supervisors of the principal investigator and responsible for the medical and scientific content of the manuscript. IFN and CMJRS are student investigators and were responsible for a considerable part of the data collection. DJMV is the founder of the cohort and responsible for the preliminary diagnostic studies. PELMR and ADMK are responsible for the statistical analyses of the data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript and agree with publication of their names.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Geel, A.C., Geusens, P.P., Nagtzaam, I.F. et al. Timing and risk factors for clinical fractures among postmenopausal women: a 5-year prospective study. BMC Med 4, 24 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-4-24

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-4-24