Abstract

Background

The ABC transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp) is recognized as a site for drug-drug interactions and provides a mechanistic explanation for clinically relevant pharmacokinetic interactions with digoxin. The question of whether several P-gp inhibitors may have additive effects has not yet been addressed.

Methods

We evaluated the effects on serum concentrations of digoxin (S-digoxin) in 618 patients undergoing therapeutic drug monitoring. P-gp inhibitors were classified as Class I, with a known effect on digoxin kinetics, or Class II, showing inhibition in vitro but no documented effect on digoxin kinetics in humans. Mean S-digoxin values were compared between groups of patients with different numbers of coadministered P-gp inhibitors by a univariate and a multivariate model, including the potential covariates age, sex, digoxin dose and total number of prescribed drugs.

Results

A large proportion (47%) of the digoxin patients undergoing therapeutic drug monitoring had one or more P-gp inhibitor prescribed. In both univariate and multivariate analysis, S-digoxin increased in a stepwise fashion according to the number of coadministered P-gp inhibitors (all P values < 0.01 compared with no P-gp inhibitor). In multivariate analysis, S-digoxin levels were 1.26 ± 0.04, 1.51 ± 0.05, 1.59 ± 0.08 and 2.00 ± 0.25 nmol/L for zero, one, two and three P-gp inhibitors, respectively. The results were even more pronounced when we analyzed only Class I P-gp inhibitors (1.65 ± 0.07 for one and 1.83 ± 0.07 nmol/L for two).

Conclusions

Polypharmacy may lead to multiple drug-drug interactions at the same site, in this case P-gp. The S-digoxin levels increased in a stepwise fashion with an increasing number of coadministered P-gp inhibitors in patients taking P-gp inhibitors and digoxin concomitantly. As coadministration of digoxin and P-gp inhibitors is common, it is important to increase awareness about P-gp interactions among prescribing clinicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Knowledge about mechanisms of interactions makes it possible to predict and prevent pharmacokinetic drug interactions. The MDR1 gene encodes the ABC transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which functions as an efflux pump and is recognized as a site for drug-drug interactions [1–5]. Several commonly used drugs inhibit P-gp efflux, which can increase gastrointestinal absorption, decrease elimination in the bile and urine, and affect the distribution of drugs to certain compartments, such as the central nervous system (CNS) [2–5].

Digoxin has a narrow therapeutic range and is recognized as a high-affinity P-gp substrate [6]. Risk factors for digoxin toxicity are well known to clinicians and include advanced age, impaired renal function and low body weight. Despite this, statistics show that unintended digoxin intoxication remains a common problem [7]. Digoxin has again become a subject of discussion after recent publications demonstrated sex-based differences in mortality [8] and increased mortality among men with serum concentrations of digoxin (S-digoxin) > 1.5 nmol/L [9]. In this context, heightened attention to a patient's S-digoxin level is warranted.

Certain inhibitors of P-gp have been demonstrated to increase S-digoxin levels in healthy volunteers [2, 10, 11], sometimes in a dose-dependent manner [12]. As digoxin is frequently coadministered with P-gp inhibitors, we wanted to i) evaluate whether clinically relevant interactions are observed in a large group of ordinary digoxin patients and ii) investigate whether patients taking several P-gp inhibitors have additive elevations in S-digoxin levels compared with patients with one concomitantly prescribed P-gp inhibitor.

Methods

Study population and analysis of S-digoxin

All patients on digoxin therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) at Uppsala University hospital (Sweden) over the past three years were considered for this study. Patients were included if they were on oral digoxin treatment; their S-digoxin values were above the detection limit; steady-state concentrations had been reached; the serum samples were measured at trough; and information about concomitant treatment was available.

The S-digoxin levels had been determined by a fluorescence polarization immunoassay (TDx®, Abbott Scandinavia AB, Sweden).

Substance classification

To classify the concomitantly administered drugs as P-gp inhibitors, PubMed was systematically searched for the INN substance name and English spelling combined with the terms 'P-gp', 'Pgp' and 'MDR1'. Substances were classified as P-gp inhibitors when demonstrating a clear inhibitory effect on P-gp in cellular transport assays, in cellular uptake assays or in animal models using mdr1a(-/-)mice. A literature review was also performed combining the search terms 'digoxin' and the substance names. Any effect of each drug on digoxin pharmacokinetics in vivo was documented.

To evaluate whether only P-gp inhibitors with well-recognized digoxin interactions in vivo contribute to a change in S-digoxin, the P-gp inhibitors were further divided into two groups: Class I P-gp inhibitors, with well-documented effects on digoxin pharmacokinetics in vivo, and Class II P-gp inhibitors, with established P-gp inhibitory effect in vitro and putative effects on S-digoxin in vivo. Class I and II P-gp inhibitors were compared with drugs that had no or unknown effects on P-gp. Only substances administered orally were included in the classification.

Statistical analysis

Adjusted mean S-digoxin values for each category of P-gp were computed on the basis of the regression estimates calculated with the General Linear Model using Proc GLM in SAS 8.02 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA), with the confounding factors at their mean values. Data are presented as mean values ± SE. Two different models were used: one univariate and one multivariate, including the potential covariates age, sex, digoxin dose and total number of prescribed drugs for each individual (all continuous). In addition, subclass analysis including p-creatinine values was performed.

Results

Patient characteristics

Therapeutic drug monitoring charts from 618 patients (256 men and 362 women) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The study population included patients with a diagnosis of heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation. See Table 1 for patient characteristics. Forty-seven percent of the study population were taking at least one P-gp inhibitor. Patients with S-digoxin levels above the recommended therapeutic range, > 2.5 nmol/L, (the upper limit of the therapeutic range at the time of the study) were more likely to have coadministered P-gp inhibitors compared with patients with S-digoxin = 2.5 nmol/L (68% vs. 47%, P = 0.01, using Chi-square test).

Substance classification

Our study population had a total of 228 different drug substances prescribed. Of these, 21 were documented P-gp inhibitors and eight were P-gp inhibitors with reported digoxin interactions (Table 2).

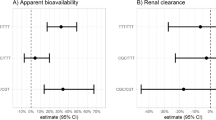

Association between S-digoxin levels and number of coadministered P-gp inhibitors

Overall, patients with concomitant P-gp inhibitors had higher S-digoxin levels than patients without: 1.55 ± 0.04 compared with 1.26 ± 0.04 nmol/L, P < 0.001 (the results differed in the third decimal between the univariate and multivariate analyses [Figure 1A]). Subclass analysis of the 542 patients for whom p-creatinine was available did not alter these results. An increasing number of P-gp inhibitors was associated with stepwise elevations in S-digoxin levels (Figure 1B).

The association between S-digoxin levels and the number of prescribed P-gp inhibitors (A) Adjusted* S-digoxin means for the patients without ('0') (N = 328, S-digoxin mean ± SE 1.26 ± 0.04 nmol/L) or with ('≥ 1'), P-gp inhibitors (N = 290, S-digoxin mean ± SE 1.55 ± 0.04 nmol/L). (B) Adjusted* S-digoxin means for patients taking zero, one, two or three P-gp inhibitors. The number of patients were 328, 204, 78 and eight, respectively. The S-digoxin means ± SE (nmol/L) were 1.26 ± 0.04, 1.51 ± 0.05, 1.59 ± 0.08 and 2.00 ± 0.25. *Adjusted for age, sex, digoxin dose and total number of prescribed drugs.

Analysis of classified P-gp inhibitors

The S-digoxin levels were 1.25 ± 0.04 nmol/L for patients with no P-gp inhibitors compared with 1.65 ± 0.07 and 1.83 ± 0.17 for patients with one and two Class I P-gp inhibitors, respectively (Figure 2). The differences in the calculations using the univariate compared with the multivariate model were minute. The effect on mean S-digoxin levels among patients with Class I P-gp inhibitors was not solely attributed to the most frequently coadministered P-gp inhibitors, spironolactone and verapamil, because exclusion of patients with these drugs gave similar, although smaller, differences. Patients taking one or two Class II P-gp inhibitors also tended to have elevated S-digoxin levels compared with patients with no P-gp inhibitors, although these differences were not significant in the multivariate model.

The association between S-digoxin levels and the number of prescribed Class I P-gp inhibitors Adjusted* S-digoxin means for patients taking zero, one or two Class I P-gp inhibitors. The numbers of patients were 328, 96 and 17, respectively. The S-digoxin means ± SE (nmol/L) were 1.25 ± 0.04, 1.65 ± 0.07 and 1.83 ± 0.17. *Adjusted for age, sex, digoxin dose and total number of prescribed drugs.

Discussion

Rathore et al. (2003) [9] recently reported that the mortality rate was increased at S-digoxin levels above 1.5 nmol/L. Therefore, it is particularly important to be aware of factors that influence S-digoxin levels. We consider the magnitudes of the differences seen in S-digoxin in this study, 20–60% increases, to be of clinical importance. The patients taking one or more P-gp inhibitor had S-digoxin levels above 1.5 nmol/L, while patients without P-gp inhibitors were below this limit.

Pharmacokinetic interactions with digoxin can arise from mechanisms other than P-gp, for example, changes in renal function, changes in gut motility or pH, disturbances of digoxin-metabolizing intestinal bacteria or possibly from interactions with other transport proteins, such as members of the solute carrier family (SLC) [13]. P-gp seems, however, to be a major determinant for digoxin pharmacokinetics.

Drugs with structures similar to digoxin can interfere with digoxin immunoassays [14]. Of the concomitant drugs taken by the patients in this study, spironolactone and its metabolites have been reported to interfere with the digoxin readings [15]. That spironolactone can interfere with digoxin immunoassays has been known for 30 years [16], but until recently little information about this effect has been available for newer digoxin assays. In a 1999 report by Steimer et al. [17], a case of digoxin toxicity resulted from falsely low values using the MEIA II assay for digoxin (AxSYM®; Abbott). Canrenone and spironolactone were identified as the major interfering substances. In a subsequent study, Steimer et al. (2002) [15] examined nine digoxin assays including the TDx® used in our study. False-negative results were attributable to spironolactone, canrenone and other steroids in several newer digoxin assays. In contrast, falsely increased digoxin concentrations could be detected in the TDx assay®, although these were very small except in the absence of digoxin and at high concentrations of the interfering substance. In updated product information for the TDx assay® released by Abbott Scandinavia AB [18], the results of a careful study of the analytical interference from spironolactone, canrenone and other steroids confirmed the results of Steimer et al. [15]. Spironolactone and canrenone, at concentrations estimated to be the maximal blood concentrations found in patients treated with these drugs, were shown to increase the digoxin concentration by 4% and 15%, respectively. Spironolactone metabolites at concentrations corresponding to a daily intake of 100 mg falsely increased the digoxin concentration by 7%.

It is important to note that the doses recommended for patients with heart failure are considerably lower than this (12.5–50 mg). The average intake in our study was 34 mg/day. Furthermore, our results cannot be due to assay interference because the association between serum digoxin concentrations and P-gp inhibitors remains statistically significant even when all patients on spironolactone are excluded from the study (1.46 ± 0.05 compared with 1.26 ± 0.04 nmol/L, P < 0.001, for patients with and without concomitant P-gp inhibitors, respectively).

Likely explanations for the more pronounced effect of Class I P-gp inhibitors on S-digoxin levels compared with Class II P-gp inhibitors are the inhibitory concentrations for a certain drug in relation to the concentrations achieved in clinical use. As the drugs have been evaluated for P-gp inhibitory effect using several different in vitro methods, it was not proper to perform a comparison of the Ki or IC50 values from the literature. A majority of the Class I inhibitors are given at higher doses than Class II inhibitors (the range of the lowest recommended doses is 10–200 mg for Class I vs. 0.25–60 mg for Class II), and the Class I inhibitors are often more potent, inhibiting digoxin transport by P-gp in vitro at lower concentrations. Other factors, such as time-point for the administration and physiochemical properties of the drug, might also contribute to the effect seen in vivo. Today, the in vitro data used to select the Class II drugs is not sufficient for the prediction of clinically relevant P-gp interactions in vivo. Before such interactions are fully understood, the Class II drugs should be regarded as potential mediators of drug-drug interactions when coadministered with digoxin or other P-gp substrates.

P-gp has a broad substrate specificity and, unfortunately, it is not possible to state that a particular group of drugs, for example, calcium channel blockers or HMG-coenzyme A inhibitors, are P-gp inhibitors with potential clinical consequences. For instance, verapamil is a P-gp inhibitor demonstrating clinical effects on digoxin kinetics, whereas diltiazem is not [19]. Similarly, the HMG-coenzyme A inhibitor pravastatin is not an in vitro P-gp inhibitor [20], in contrast to atorvastatin, which is an in vitro P-gp inhibitor that also demonstrates in vivo effects on P-gp [11]. Any investigation of P-gp inhibitory effects and possible clinical consequences should, therefore, be made for each single drug entity.

Conclusions

In this report we show that coadministration of P-gp inhibitors with digoxin is associated with significant elevations in S-digoxin levels in an ordinary group of digoxin patients. To avoid exposing patients to excessive digoxin levels, prescribing clinicians should consider potential P-gp interactions. Particular notice should be taken when more than one P-gp inhibitor is coadministered with digoxin, as administration of more than one P-gp inhibitor is associated with additive elevations in S-digoxin levels.

References

Fromm MF, Kim RB, Stein CM, Wilkinson GR, Roden DM: Inhibition of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport: A unifying mechanism to explain the interaction between digoxin and quinidine. Circulation. 1999, 99: 552-557.

Drescher S, Glaeser H, Murdter T, Hitzl M, Eichelbaum M, Fromm MF: P-glycoprotein-mediated intestinal and biliary digoxin transport in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002, 73: 223-231. 10.1067/mcp.2003.27.

Lown KS, Mayo RR, Leichtman AB, Hsiao HL, Turgeon DK, Schmiedlin-Ren P, Brown MB, Guo W, Rossi SJ, Benet LZ, Watkins PB: Role of intestinal P-glycoprotein (mdr1) in interpatient variation in the oral bioavailability of cyclosporine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997, 62: 248-260.

Schinkel AH, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, Borst P: Absence of the mdr1a P-glycoprotein in mice affects tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone, digoxin, and cyclosporin A. J Clin Invest. 1995, 96: 1698-1705.

Sadeque AJ, Wandel C, He H, Shah S, Wood AJ: Increased drug delivery to the brain by P-glycoprotein inhibition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000, 68: 231-237. 10.1067/mcp.2000.109156.

Tanigawara Y, Okamura N, Hirai M, Yasuhara M, Ueda K, Kioka N, Komano T, Hori R: Transport of digoxin by human P-glycoprotein expressed in a porcine kidney epithelial cell line (LLC-PK1). J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992, 263: 840-845.

Juurlink DN, Mamdani M, Kopp A, Laupacis A, Redelmeier DA: Drug-drug interactions among elderly patients hospitalized for drug toxicity. JAMA. 2003, 289: 1652-1658. 10.1001/jama.289.13.1652.

Rathore SS, Wang Y, Krumholz HM: Sex-based differences in the effect of digoxin for the treatment of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 1403-11. 10.1056/NEJMoa021266.

Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM: Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2003, 289: 871-878. 10.1001/jama.289.7.871.

Westphal K, Weinbrenner A, Giessmann T, Stuhr M, Franke G, Zschiesche M, Oertel R, Terhaag B, Kroemer HK, Siegmund W: Oral bioavailability of digoxin is enhanced by talinolol: evidence for involvement of intestinal P-glycoprotein. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000, 68: 6-12. 10.1067/mcp.2000.107579.

Boyd RA, Stern RH, Stewart BH, Wu X, Reyner EL, Zegarac EA, Randinitis EJ, Whitfield L: Atorvastatin coadministration may increase digoxin concentrations by inhibition of intestinal P-glycoprotein-mediated secretion. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000, 40: 91-98. 10.1177/00912700022008612.

Tanaka H, Matsumoto K, Ueno K, Kodama M, Yoneda K, Katayama Y, Miyatake K: Effect of clarithromycin on steady-state digoxin concentrations. Ann Pharmacother. 2003, 37: 178-181. 10.1345/aph.1C203.

Kodawara T, Masuda S, Wakasugi H, Uwai Y, Futami T, Saito H, Abe T, Inu K: Organic anion transporter oatp2-mediated interaction between digoxin and amiodarone in the rat liver. Pharm Res. 2002, 19: 738-743. 10.1023/A:1016184211491.

Thomas RW, Maddox RR: The interaction of spironolactone and digoxin: a review and evaluation. Ther Drug Monit. 1981, 3: 117-120.

Steimer W, Muller C, Eber B: Digoxin assays: frequent, substantial, and potentially dangerous interference by spironolactone, canrenone, and other steroids. Clin Chem. 2002, 48: 507-516.

Philips AP: The improvement of specificity in radioimmunoassay. Clin Chim Acta. 1973, 44: 333-340. 10.1016/0009-8981(73)90075-2.

Steimer W, Muller C, Eber B, Emmanuilidis K: Intoxication due to negative canrenone interference in digoxin drug monitoring. Lancet. 1999, 354: 1176-1177. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03818-0.

Abbot laboratories. 23 July 2003, [http://www.abbott.com]

Rameis H, Magometschnigg D, Ganzinger U: The diltiazem-digoxin interaction. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984, 36: 183-189.

Wang E, Casciano CN, Clement RP, Johnson WW: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) characterized as direct inhibitors of P-glycoprotein. Pharm Res. 2001, 18: 800-806. 10.1023/A:1011036428972.

Kakumoto M, Takara K, Sakaeda T, Tanigawara Y, Kita T, Okumura K: MDR1-mediated interaction of digoxin with antiarrhythmic or antianginal drugs. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002, 25: 1604-1607. 10.1248/bpb.25.1604.

Laer S, Scholz H, Buschmann I, Thoenes M, Meinertz T: Digitoxin intoxication during concomitant use of amiodarone. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998, 54: 95-96. 10.1007/s002280050427.

Okamura N, Hirai M, Tanigawara Y, Tanaka K, Yasuhara M, Ueda K, Komano T, Hori R: Digoxin-cyclosporin A interaction: modulation of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein in the kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993, 266: 1614-1619.

Verstuyft C, Strabach S, Morabet H, Kerb R, Brinkmann U, Dubert L, Jaillon P, Funck-Brentano C, Trugnan G, Becquemont L: Dipyridamole enhances digoxin bioavailability via P-glycoprotein inhibition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003, 73: 51-60. 10.1067/mcp.2003.8.

Nakamura T, Kakumoto M, Yamashita K, Takara K, Tanigawara Y, Sakaeda T, Okumura K: Factors influencing the prediction of steady state concentrations of digoxin. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001, 24: 403-408. 10.1248/bpb.24.403.

van der Sandt IC, Blom-Roosemalen MC, de Boer AG, Breimer DD: Specificity of doxorubicin versus rhodamine-123 in assessing P-glycoprotein functionality in the LLC-PK1, LLC-PK1:MDR1 and Caco-2 cell lines. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000, 11: 207-214. 10.1016/S0928-0987(00)00097-X.

Hedman A, Angelin B, Arvidsson A, Dahlqvist R, Nilsson B: Interactions in the renal and biliary elimination of digoxin: stereoselective difference between quinine and quinidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990, 47: 20-26.

Yasuda K, Lan LB, Sanglard D, Furuya K, Schuetz JD, Schuetz EG: Interaction of cytochrome P450 3A inhibitors with P-glycoprotein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002, 303: 323-332. 10.1124/jpet.102.037549.

Dey S, Hafkemeyer P, Pastan I, Gottesman MM: A single amino acid residue contributes to distinct mechanisms of inhibition of the human multidrug transporter by stereoisomers of the dopamine receptor antagonist flupentixol. Biochemistry. 1999, 38: 6630-6639. 10.1021/bi983038l.

Golstein PE, Boom A, van Geffel J, Jacobs P, Masereel B, Beauwens R: P-glycoprotein inhibition by glibenclamide and related compounds. Pflugers Arch. 1999, 437: 652-660. 10.1007/s004240050829.

Rodin SM, Johnson BF, Wilson J, Ritchie P, Johnson J: Comparative effects of verapamil and isradipine on steady-state digoxin kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988, 43: 668-672.

Pauli-Magnus C, Rekersbrink S, Klotz U, Fromm MF: Interaction of omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole with P-glycoprotein. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001, 364: 551-557. 10.1007/s00210-001-0489-7.

Schinkel AH, Wagenaar E, Mol CA, van Deemter L: P-glycoprotein in the blood-brain barrier of mice influences the brain penetration and pharmacological activity of many drugs. J Clin Invest. 1996, 97: 2517-2524.

Wandel C, Kim R, Wood M, Wood A: Interaction of morphine, fentanyl, sufentanil, alfentanil, and loperamide with the efflux drug transporter P-glycoprotein. Anesthesiology. 2002, 96: 913-920.

Claudio JA, Emerman JT: The effects of cyclosporin A, tamoxifen, and medroxyprogesterone acetate on the enhancement of adriamycin cytotoxicity in primary cultures of human breast epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996, 41: 111-122.

Weiss J, Dormann SM, Martin-Facklam M, Kerpen CJ, Ketabi-Kiyanvash N, Haefeli WE: Inhibition of P-glycoprotein by newer antidepressants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003, 305: 197-204. 10.1124/jpet.102.046532.

Rapeport WG, Coates PE, Dewland PM, Forster PL: Absence of a sertraline-mediated effect on digoxin pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic findings. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996, 57 (Suppl 1): 16-19.

Raeissi SD, Hidalgo IJ, Segura-Aguilar J, Artursson P: Interplay between CYP3A-mediated metabolism and polarized efflux of terfenadine and its metabolites in intestinal epithelial Caco-2 (TC7) cell monolayers. Pharm Res. 1999, 16: 625-632. 10.1023/A:1018851919674.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/2/8/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research and Swedish Research Council grant no. 9478.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

GE participated in the collection of the patient material, the computer analysis of the data, the classification of P-gp-inhibitors and in the writing of the manuscript. PH participated in the collection of the patient material, the computer analysis of the data and in the writing of the manuscript. PA participated in the analysis of the data and in the writing of the manuscript. KM participated in the in the computer analysis of the data. HM conceived the study and participated in its design and in the writing of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Englund, G., Hallberg, P., Artursson, P. et al. Association between the number of coadministered P-glycoprotein inhibitors and serum digoxin levels in patients on therapeutic drug monitoring. BMC Med 2, 8 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-8