Abstract

Background and Objective

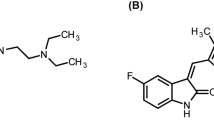

An increasing trend in prescribing proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) inevitably increases the risk of unwanted drug–drug interactions (DDIs). The aim of this study was to uncover pharmacokinetic interactions between two PPIs—omeprazole and pantoprazole—and venlafaxine.

Methods

A therapeutic drug monitoring database contained plasma concentrations of venlafaxine and its active metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine. We considered three groups: a group of patients who received venlafaxine without confounding medications (non-PPI group, n = 906); a group of patients who were comedicated with omeprazole (n = 40); and a group of patients comedicated with pantoprazole (n = 40). Plasma concentrations of venlafaxine, O-desmethylvenlafaxine and active moiety (venlafaxine + O-desmethylvenlafaxine), as well as dose-adjusted plasma concentrations, were compared using non-parametrical tests.

Results

Daily doses of venlafaxine did not differ between groups (p = 0.949). The Mann–Whitney U test showed significantly higher plasma concentrations of active moiety, as well as venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine, in both PPI groups [p = 0.023, p = 0.011, p = 0.026, +29% active moiety, +27% venlafaxine, +36% O-desmethylvenlafaxine (pantoprazole); p = 0.003, p = 0.039 and p < 0.001, +36% active moiety, +27% venlafaxine, +55% O-desmethylvenlafaxine (omeprazole)]. Significantly higher concentration-by-dose (C/D) values for venlafaxine and active moiety were detected in the pantoprazole group (p = 0.013, p = 0.006, respectively), while in the omeprazole group, C/D ratios for all three parameters—venlafaxine, O-desmethylvenlafaxine and active moiety—were significantly higher (p = 0.021, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Significantly higher plasma concentrations for all parameters (venlafaxine, O-desmethylvenlafaxine, active moiety) suggest clinically relevant inhibitory effects of both PPIs, most likely on the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19-mediated metabolism of venlafaxine. The findings might be the result of different degrees of CYP2C19 involvement, therefore the inhibition of CYP2C19 by both PPIs may lead to an increased metabolism via CYP2D6 to O-desmethylvenlafaxine.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Patterson SM, Cadogan CA, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC, Ryan C, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD008165. doi:10.1002/14651858

Stingl JC, Kaumanns KL, Claus K, Lehmann ML, Kastenmuller K, Bleckwenn M, et al. Individualized versus standardized risk assessment in patients at high risk for adverse drug reactions (IDrug)—study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:49.

Cadieux RJ. Drug interactions in the elderly. How multiple drug use increases risk exponentially. Postgrad Med. 1989;86(8):179–86.

Paulzen M, Haen E, Gründer G, Lammertz SE, Stegmann B, Schruers KR, et al. Pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of hypertension in risperidone-medicated patients—thinking of clinically relevant CYP2D6 interactions. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf, Engl). 2016;30(8):803–9.

Schoretsanitis G, Stegmann B, Hiemke C, Gründer G, Schruers KR, Walther S, et al. Pharmacokinetic patterns of risperidone-associated adverse drug reactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(9):1091–8.

Schoretsanitis G, Haen E, Hiemke C, Gründer G, Stegmann B, Schruers KR, et al. Risperidone-induced extrapyramidal side effects: is the need for anticholinergics the consequence of high plasma concentrations? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(5):259–64.

Morkem R, Barber D, Williamson T, Patten SB. A Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network study evaluating antidepressant prescribing in Canada from 2006 to 2012. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(12):564–70.

Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818–31.

Schwabe U, Paffrath D. Arzneiverordnungs-report 2015: Berlin. Heidelberg: Springer; 2015.

Calderon-Larranaga A, Gimeno-Feliu LA, Gonzalez-Rubio F, Poblador-Plou B, Lairla-San Jose M, Abad-Diez JM, et al. Polypharmacy patterns: unravelling systematic associations between prescribed medications. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84967.

Gjestad C, Westin AA, Skogvoll E, Spigset O. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on the serum concentrations of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(1):90–7.

Rocha A, Coelho EB, Sampaio SA, Lanchote VL. Omeprazole preferentially inhibits the metabolism of (+)-(S)-citalopram in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70(1):43–51.

Bondolfi G, Morel F, Crettol S, Rachid F, Baumann P, Eap CB. Increased clozapine plasma concentrations and side effects induced by smoking cessation in 2 CYP1A2 genotyped patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27(4):539–43.

Fogelman SM, Schmider J, Venkatakrishnan K, von Moltke LL, Harmatz JS, Shader RI, et al. O- and N-demethylation of venlafaxine in vitro by human liver microsomes and by microsomes from cDNA-transfected cells: effect of metabolic inhibitors and SSRI antidepressants. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20(5):480–90.

Patroneva A, Connolly SM, Fatato P, Pedersen R, Jiang Q, Paul J, et al. An assessment of drug-drug interactions: the effect of desvenlafaxine and duloxetine on the pharmacokinetics of the CYP2D6 probe desipramine in healthy subjects. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(12):2484–91.

Nichols AI, Fatato P, Shenouda M, Paul J, Isler JA, Pedersen RD, et al. The effects of desvenlafaxine and paroxetine on the pharmacokinetics of the cytochrome P450 2D6 substrate desipramine in healthy adults. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(2):219–28.

Ogilvie BW, Yerino P, Kazmi F, Buckley DB, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Paris BL, et al. The proton pump inhibitor, omeprazole, but not lansoprazole or pantoprazole, is a metabolism-dependent inhibitor of CYP2C19: implications for coadministration with clopidogrel. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39(11):2020–33.

Haen E. Therapeutic drug monitoring in pharmacovigilance and pharmacotherapy safety. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):254–8.

Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, Conca A, Dietmaier O, Egberts K, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195–235.

US Food and Drug Administration. Drug development and drug interactions: table of substrates, inhibitors and inducers. 2014. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugInteractionsLabeling/ucm093664.htm. Accessed 27 Jun 2017.

Shams ME, Arneth B, Hiemke C, Dragicevic A, Müller MJ, Kaiser R, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphism and clinical effect of the antidepressant venlafaxine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31(5):493–502.

Schmitt G, Herbold M, Peters F. Methodenvalidierung im forensisch-toxikologischen Labor: Auswertung von Validierungsdaten nach den Richtlinien der GTFCh mit VALISTAT: Arvecon GmbH; 2003.

Liu TJ, Jackevicius CA. Drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(3):275–89.

Curi-Pedrosa R, Daujat M, Pichard L, Ourlin JC, Clair P, Gervot L, et al. Omeprazole and lansoprazole are mixed inducers of CYP1A and CYP3A in human hepatocytes in primary culture. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269(1):384–92.

Rost KL, Brosicke H, Heinemeyer G, Roots I. Specific and dose-dependent enzyme induction by omeprazole in human beings. Hepatology. 1994;20(5):1204–12.

Frick A, Kopitz J, Bergemann N. Omeprazole reduces clozapine plasma concentrations. A case report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(3):121–3.

Buchthal J, Grund KE, Buchmann A, Schrenk D, Beaune P, Bock KW. Induction of cytochrome P4501A by smoking or omeprazole in comparison with UDP-glucuronosyltransferase in biopsies of human duodenal mucosa. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;47(5):431–5.

Mookhoek EJ, Loonen AJ. Retrospective evaluation of the effect of omeprazole on clozapine metabolism. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(3):180–2.

Karlsson L, Zackrisson AL, Josefsson M, Carlsson B, Green H, Kugelberg FC. Influence of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes on venlafaxine metabolic ratios and stereoselective metabolism in forensic autopsy cases. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15(2):165–71.

Klamerus KJ, Maloney K, Rudolph RL, Sisenwine SF, Jusko WJ, Chiang ST. Introduction of a composite parameter to the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine and its active O-desmethyl metabolite. J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;32(8):716–24.

Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlstrom M, Weidolf L. Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(8):821–7.

Klotz U, Schwab M, Treiber G. CYP2C19 polymorphism and proton pump inhibitors. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;95(1):2–8.

Topic E, Stefanovic M, Samardzija M. Association between the CYP2C9 polymorphism and the drug metabolism phenotype. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42(1):72–8.

Gawronska-Szklarz B, Adamiak-Giera U, Wyska E, Kurzawski M, Gornik W, Kaldonska M, et al. CYP2C19 polymorphism affects single-dose pharmacokinetics of oral pantoprazole in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(9):1267–74.

Ichikawa H, Sugimoto M, Sugimoto K, Andoh A, Furuta T. Rapid metabolizer genotype of CYP2C19 is a risk factor of being refractory to proton pump inhibitor therapy for reflux esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(4):716–26.

Sagar M, Bertilsson L, Stridsberg M, Kjellin A, Mardh S, Seensalu R. Omeprazole and CYP2C19 polymorphism: effects of long-term treatment on gastrin, pepsinogen I, and chromogranin A in patients with acid related disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(11):1495–502.

Payan M, Rouini MR, Tajik N, Ghahremani MH, Tahvilian R. Hydroxylation index of omeprazole in relation to CYP2C19 polymorphism and sex in a healthy Iranian population. Daru. 2014;22:81.

Deshpande N, Sharanya V, Ravi Kanth VV, Murthy HVV, Sasikala M, Banerjee R, et al. Rapid and ultra-rapid metabolizers with CYP2C19*17 polymorphism do not respond to standard therapy with proton pump inhibitors. Meta Gene. 2016;9:159–64.

Stamm TJ, Becker D, Sondergeld LM, Wiethoff K, Hiemke C, O’Malley G, et al. Prediction of antidepressant response to venlafaxine by a combination of early response assessment and therapeutic drug monitoring. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2014;47(4–5):174–9.

Steen NE, Aas M, Simonsen C, Dieset I, Tesli M, Nerhus M, et al. Serum level of venlafaxine is associated with better memory in psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2015;169(1–3):386–92.

Lobello KW, Preskorn SH, Guico-Pabia CJ, Jiang Q, Paul J, Nichols AI, et al. Cytochrome P450 2D6 phenotype predicts antidepressant efficacy of venlafaxine: a secondary analysis of 4 studies in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(11):1482–7.

Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, Clarke GN, Wagner KD, Vitiello B, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92–7.

Pauli-Magnus C, Rekersbrink S, Klotz U, Fromm MF. Interaction of omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole with P-glycoprotein. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364(6):551–7.

Hendset M, Haslemo T, Rudberg I, Refsum H, Molden E. The complexity of active metabolites in therapeutic drug monitoring of psychotropic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39(4):121–7.

Bachmeier CJ, Beaulieu-Abdelahad D, Ganey NJ, Mullan MJ, Levin GM. Induction of drug efflux protein expression by venlafaxine but not desvenlafaxine. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2011;32(4):233–44.

Gursoy O, Memis D, Sut N. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on gastric juice volume, gastric pH and gastric intramucosal pH in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig. 2008;28(12):777–82.

Paulzen M, Haen E, Stegmann B, Hiemke C, Gründer G, Lammertz SE, et al. Body mass index (BMI) but not body weight is associated with changes in the metabolism of risperidone. A pharmacokinetics-based hypothesis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;18(73):9–15.

Hassan-Alin M, Andersson T, Niazi M, Rohss K. A pharmacokinetic study comparing single and repeated oral doses of 20 mg and 40 mg omeprazole and its two optical isomers, S-omeprazole (esomeprazole) and R-omeprazole, in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60(11):779–84.

Dadabhai A, Friedenberg FK. Rabeprazole: a pharmacologic and clinical review for acid-related disorders. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8(1):119–26.

Klamerus KJ, Parker VD, Rudolph RL, Derivan AT, Chiang ST. Effects of age and gender on venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine pharmacokinetics. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(5):915–23.

Unterecker S, Hiemke C, Greiner C, Haen E, Jabs B, Deckert J, et al. The effect of age, sex, smoking and co-medication on serum levels of venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine under naturalistic conditions. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2012;45(6):229–35.

Reis M, Lundmark J, Bjork H, Bengtsson F. Therapeutic drug monitoring of racemic venlafaxine and its main metabolites in an everyday clinical setting. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24(4):545–53.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the significant number of people who contributed with their excellent professional, technical, and pharmacological competence to build up the KONBEST database with 50,049 clinical pharmacological comments as of 2 February 2016 (ranked among the professional groups in historical order): A. Köstlbacher created the KONBEST software in his PhD thesis, based on an idea by E. Haen, C. Greiner, and D. Melchner, along the workflow in the clinical pharmacological laboratory at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Regensburg. A. Köstlbacher, along with his colleague A. Haas, continuously maintain the KONBEST software and its data-mining platform (Haas & Köstlbacher GbR, Regensburg, Germany). Laboratory technicians performed the quantitative analysis: D. Melchner, T. Jahner, S. Beck, A. Dörfelt, U. Holzinger, and F. Pfaff-Haimerl. The clinical pharmacological comments regarding drug concentrations were composed by licensed pharmacists and medical doctors. Licensed pharmacists: C. Greiner, W. Bader, R. Köber, A. Hader, R. Brandl, M. Onuoha, N. Ben Omar, K. Schmid, A. Köppl, M. Silva, B. Fay, S. Unholzer, C. Rothammer, S. Böhr, F. Ridders, D. Braun, M. Schwarz, M. Dobmeier, M. Wittmann, M. Vogel, M. Böhme, K. Wenzel-Seifert, B. Plattner, P. Holter, R. Böhm, and R. Knorr. Furthermore, the authors thank Mrs. Paraskevi Giannakaki for her expertise in statistics, and Dr. Sarah E. Lammertz for her ability to transfer numbers into intriguing figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

Ekkehard Haen received speaker’s or consultancy fees from the following pharmaceutical companies: Servier, Novartis, and Janssen-Cilag. He is managing director of AGATE, a non-profit working group to improve drug safety and efficacy in the treatment of psychiatric diseases. He reports no conflicts of interest with this publication. Christoph Hiemke has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Janssen-Cilag and Servier. He is managing director of psiac GmbH, which provides an internet-based DDI program for psychopharmacotherapy. He reports no conflicts of interest with this publication. Gerhard Gründer has served as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany), Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Lundbeck (Copenhagen, Denmark), Ono Pharmaceuticals (Osaka, Japan), Roche (Basel, Switzerland), Servier (Paris, France), and Takeda (Osaka, Japan). He has served on the speakers’ bureau of Eli Lilly, Gedeon Richter (Budapest, Hungary), Janssen Cilag (Neuss, Germany), Lundbeck, Roche, Servier, and Trommsdorf (Aachen, Germany), and has received grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. He is co-founder of Pharma Image GmbH (Düsseldorf, Germany) and Brainfoods GmbH (Selfkant, Germany). He reports no conflicts of interest with this publication. Georgios Schoretsanitis received a grant from the bequest ‘in memory of Maria Zaoussi’, State Scholarships Foundation, Greece, for clinical research in psychiatry for the academic year 2015–2016. Maxim Kuzin, Benedikt Stegmann, Michael Paulzen declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The research study did not receive funds or support from any source.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuzin, M., Schoretsanitis, G., Haen, E. et al. Effects of the Proton Pump Inhibitors Omeprazole and Pantoprazole on the Cytochrome P450-Mediated Metabolism of Venlafaxine. Clin Pharmacokinet 57, 729–737 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0591-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0591-8