Abstract

Background

Dyskinesia, a major complication in the treatment of Parkinson's disease (PD), can require prolonged monitoring and complex medical management.

Discussion

The current paper proposes a new way to view the management of dyskinesia in an integrated fashion. We suggest that dyskinesia be considered as a factor in a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) equation where the signal is the voluntary movement and the noise is PD symptomatology, including dyskinesia. The goal of clinicians should be to ensure a high SNR in order to maintain or enhance the motor repertoire of patients. To understand why such an approach would be beneficial, we first review mechanisms of dyskinesia, as well as their impact on the quality of life of patients and on the health-care system. Theoretical and practical bases for the SNR approach are then discussed.

Summary

Clinicians should not only consider the level of motor symptomatology when assessing the efficacy of their treatment strategy, but also breadth of the motor repertoire available to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by a predominant loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta [1] leading to the development of motor symptoms. Four cardinal motor symptoms are associated with PD: tremor, muscle rigidity, postural instability and akinesia/bradykinesia [2]. PD is also associated with the development of non-motor symptoms stemming from the pathological involvement of particular brain structures and complex neurochemical imbalances [3]. These symptoms include psychiatric manifestations [4], rapid eye movement and other sleep disturbances [5, 6], mood disturbance [7, 8], bradyphrenia and cognitive deficits [9–12], anosmia [13], fatigue, autonomic system dysfunction and pain [14]. Although both motor and non-motor symptoms can be disabling for patients, current treatments target predominantly the motor dysfunction using mainly dopaminergic therapies. Prolonged use of dopaminergic agents can lead to drug-induced dyskinesia.

Dyskinesia may have deleterious effects on the quality of life of both patients and their caregivers, and create an additional strain on the health-care system. While several approaches are taken by movement disorder specialists to delay or manage dyskinesia, neurologists not specialized in the treatment of movement disorders and general practitioners may find it difficult to control dyskinesia while maintaining clinically significant reductions in typical PD symptoms. In this paper, we propose a novel way to view the clinical management of dyskinesia, which could benefit patient care. In order to comprehend fully the complexity of the problem of dyskinesia, we first provide an overview of the treatments for PD and how they can induce dyskinesia. We then provide a review of the impact of dyskinesia on quality of life and health-care costs.

Discussion

How prominent is the problem of PD?

The prevalence rate of PD was estimated a few years ago to be between 100 to 200/100,000 population [15–19], with an incidence rate of 10 to 20/100,000 population [20, 21]. However, the number of PD cases is increasing and will have grown from 10 million worldwide in the late 1980s [22] to 40 million in 2020 [23] due mainly to the aging population. While most patients with PD are diagnosed after the age of 55 (see [24, 25]), about 10% of patients are diagnosed before the age of forty [26, 27] and characterized as 'young-onset PD' [22]. While most young-onset patients exhibit typical parkinsonian symptoms [28], they appear to display slower disease progression [25] and show a tendency for increased prevalence and severity of motor fluctuations and dyskinesia with prolonged L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) therapy [22, 29–32]. Early onset of motor complications may be especially relevant in these patients as they will live with the disease for longer periods [33] with a diminished quality of life [34] and impaired social and economic productivity [34, 35].

What are the current treatments of PD?

Based on the classical model of basal ganglia movement disorders [36–38], the loss of dopaminergic neurons associated with PD results in depletion of dopamine content into the neostriatum. This translates into altered basal ganglia neural activity, producing a change in the output of the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical pathways. The cardinal hypokinetic symptoms of PD result from a change in the activity of thalamo-cortical inputs to motor cortical areas which impairs voluntary movement [36, 39, 40]. Consequently, the primary goal of PD treatment is to counteract the depletion of dopamine. Since dopamine causes severe nausea, and cannot easily cross the blood brain barrier, other means of counteracting this dopaminergic deficiency have been developed (see [41] and [42] for comprehensive reviews of current treatment options). In brief, the current gold standard for the treatment of PD motor symptoms is L-DOPA [24, 25, 41, 43–46] associated with a decarboxylase inhibitor such as carbidopa [47–49]. Over the years, several compounds were developed to be used as adjuncts to L-DOPA or as replacement therapy. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors such as entacapone and tolcapone are used as adjuncts to L-DOPA in order to enhance its bioavailability [26, 50, 51]. Monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors, on the other hand, are used to extend the duration of action of L-DOPA by decreasing the metabolic degradation of dopamine in the synaptic cleft [1, 22, 29, 46, 52–55]. Another class of drugs that can be used as an adjunct or replacement to L-DOPA is dopamine agonists as they bind to dopaminergic receptors, mimicking the action of dopamine. They were initially used to reduce the dose of L-DOPA to control motor complications [24, 41] and may be considered for initial monotherapy [56, 57], especially in younger patients to delay the onset of dyskinesia.

While medications are the main therapeutic avenue for the alleviation of PD symptoms, surgical procedures can also provide symptomatic relief in some patients. Ablative surgeries have been used in the treatment of motor dysfunction in PD for several decades and can be very effective [58]. Several nuclei of the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical pathways are targeted using this technique, such as the thalamus [58–69], the globus pallidus internus (GPi) [70–80] and the subthalamic nucleus (STN) [76, 81–90]. More recently, deep brain stimulation (DBS) has become an invaluable clinical management tool for medically intractable motor symptoms. Interestingly, DBS targets the same structures that are targeted in ablative surgeries [91]. DBS therapy has the advantage that it is reversible and can be titrated but it suffers from complications and inconveniences related to prosthetic implants [92–98]. In recent years, STN and GPi DBS [95, 99–109] have become the targets of choice for effective relief of many motor symptoms associated with PD, including marked reduction of dyskinesia [110, 111]. Other structures were recently investigated for the alleviation of specific symptoms [112]. For example, the pedonculopontine nucleus (PPN) [113–116] was targeted for DBS in patients with gait and postural imbalance issues. The centro-median-parafascicular (CM/Pf) complex [117] and the zona incerta [118–121], on the other hand, were targeted in patients with tremor, as an alternative to the well-established thalamic ventrolateral (VL) nucleus. However, whether DBS within these alternative structures has an impact on dyskinesia has yet to be assessed.

Novel and experimental treatments of motor symptoms of PD, some of which are potentially disease-modifying, have also been introduced. One promising avenue is the development of novel drugs for the treatment of PD symptoms. For instance, Adenosine A2A-receptor antagonists offer the potential to provide benefits that are not delivered by traditional dopaminergic medications and might avoid dopaminergic side effects through a reduction of the over-activity in the striatopallidal pathway [122]. Many of these drugs are currently in development and are at different phases of clinical trials. Prodrugs are another class of medication currently under development. They are inactive or poorly active compounds that undergo in vivo chemical or enzymatic activation that transforms them into an active drug [123]. They have better pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties than active drugs, thus having the potential of improved oral absorption, stability and passage of the blood brain barrier. For instance, different prodrugs are under development for dopamine, dopamine receptor agonists, better use of the endogenous transport systems of the blood brain barrier as well as different peptide and glutamatergic transport systems [124]. Cell transplant approaches for PD have been considered for several decades with equivocal initial results, especially when compared to currently available treatments. However, recent work has highlighted the potential of this treatment for dopaminergic neuron replacement [125–127]. Finally, there are many potential uses for gene therapy in PD. For example, it can be used to promote the expression of agents which cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, such as neurotrophins [128–131]. Preclinical models using neurotrophic factors provided promising neuroprotective or neuroregenerative outcomes, but initial trials in humans have been mainly disappointing. Gene therapy can also be used to modify the inherent properties of neurons within specific anatomical structures. For example, gene therapy was used to modify the phenotype of STN neurons from predominantly excitatory to predominantly inhibitory in order to restore balance within the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical network [132–134]. While these are all promising treatments for PD, much work is required with regard to therapy and side effects prior to clinical application to larger patient groups. Relevant to the present paper, it is mainly unknown whether these emerging therapies may delay, treat or worsen dyskinesia.

What are the main issues with current treatments?

Long-term use of dopamimetic agents, in combination with continued dopaminergic denervation, can generate dyskinesia. Indeed, while dyskinesia are mainly associated with functional alterations within the basal ganglia pathways related to prolonged exposure to L-DOPA, dopamine agonists and DBS can also cause the appearance of dyskinesia [135–138]. The exact mechanism underlying dopamine agonist- or DBS-induced dyskinesia is still under investigation, but it is believed to stem from maladaptive mechanisms related to dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems (see [135] for review). Patients receiving intra-striatal dopaminergic neural grafts can also experience dyskinesia, also without the presence of exogenous dopaminergic agents (off-dyskinesia), possibly due to inappropriate responses to dopamine release by grafted neurons [126, 139–141].

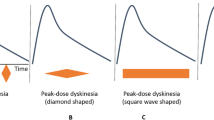

There are several different classifications or types of dyskinesia, such as dystonic, ballistic, choreic and myoclonic, which can be monophasic or bi-phasic [142–145], occurring at different times in relation to administration of dopaminergic medication. The most common dyskinesia remain the monophasic choreic type, which are involuntary movements that occur at peak-dose and are considered to be purposeless, non-rhythmic, abrupt, rapid, irregular and un-sustained [143]. We have recently provided the first characterization of the movement patterns of monophasic choreic dyskinesia based on quantitative measures of whole-body movements which highlight their complexity, and variability in amplitude and location over short periods of time [146–150]. This might explain the relative difficulty of patients to control or compensate for their dyskinesia while attempting to either plan or execute everyday motor activities.

Several risk factors are associated with the occurrence of dyskinesia including age of onset of PD [151–154], body weight [155, 156], disease duration [157, 158], and the level of exposure to L-DOPA [153, 159, 160]. A necessary factor in the development of dyskinesia appears to be the combination of dopaminergic denervation and long-term exposure to dopamine replacement therapy that promotes changes in the receptor environment and results in an altered clinical response to dopamine [161–164]. Under physiological conditions, striatal and synaptic dopamine levels are maintained at a relatively constant level [165]. The dopaminergic denervation observed in PD, in association with the administration of L-DOPA at intervals during the day, induces oscillations in the concentration of striatal and synaptic dopamine levels [166, 167]. This pulsatile stimulation of dopaminergic receptor is associated with functional changes within the basal ganglia [168, 169], which results in altered neural activity in the basal ganglia, thalamus and cerebral cortex [115] with associated involuntary movements.

Several fundamental functional alterations in the synaptic environment of the striatum are associated with development of dyskinesia. Dopaminergic denervation-induced pre-synaptic modifications occur at the cellular level which hinders dopamine homeostasis [153, 170–172]. In addition, morphological and functional alterations occur in serotoninergic neurons, which may be a homeostatic attempt to counteract the dysregulation in dopamine levels [173]. Changes also occur at the post-synaptic level where dopamine receptor trafficking [158, 174], signalling [157] and sensitivity [161, 175] are all altered in dyskinetic PD patients. Furthermore, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) [151, 152, 176, 177] as well as metabotropic glutamate receptors [178–181] have been implicated in the maladaptive plasticity associated with dyskinesia (see [135] for review). While the definite mechanisms behind their relative involvement remain to be determined, these receptors are currently being investigated as potential targets for the management of dyskinesia.

Aside from these pre- and post-synaptic changes, other functional and structural changes also play a role in the pathogenesis of dyskinesia. Astrocytes modulate the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor [182], resulting in microvascular remodelling which may be an integral part of the changes in the neural environment that lead to dyskinesia. Over-activity of adenosine A2A receptors may also play a role in the generation of dyskinesia [183–188] through facilitation of the striatopallidal pathway [189]. Additionally, modified extracellular concentrations of glutamate [190–193] as well as an altered expression of glutamate transporter genes [191, 194, 195] have been observed in different basal ganglia structures when dyskinesia are present. Finally, recent studies suggested that degeneration of inter-hemispheric striatal mechanisms may play a significant role in the genesis of dyskinesia through yet undefined mechanisms [196, 197]. Taken together, these functional alterations point towards a complex multi-factorial mechanism behind the generation and expression of dyskinesia which could explain why the management of those motor complications is so problematic.

Why is managing dyskinesia as much art as science?

Due to the complex pathophysiology of dyskinesia, there has been considerable debate about which treatment is more efficacious for best symptom management while still avoiding motor complications [28, 32–34, 40, 44, 47, 48, 51, 52, 198–201]. Several studies examined the incidence of dyskinesia with different medication (see [41] for an extensive review). Here, we focus on possible treatment options when dyskinesia have already occurred. The primary option for clinicians is to reduce medication dosage; however, this can lead to the resurgence of typical parkinsonian symptoms. The second option is to fragment dosage, reducing each dose and increasing its frequency for more constant delivery as the pulsatile delivery of L-DOPA is, in part, responsible for the observed functional alterations within the basal ganglia. The use of controlled-release oral medication may limit this pulsatile effect [202]. However, the efficacy of such controlled release drugs in treating dyskinesia is investigational at best and there is little evidence to suggest that they may delay the onset of dyskinesia [41]. Nonetheless, the concept behind controlled-release formulations, that is, a more continuous delivery of medication rather than a pulsatile increase in medication normally observed with PD medication, has spurred the development of continuous drug delivery (CDD) systems such as mini-pump guided continuous apomorphine infusion [203], duodenal L-DOPA infusion (Duodopa) [30, 201], and transdermal delivery of rotigotine (dopamine agonist) through a patch [204]. Several continuous drug delivery treatments are proposed as useful in reducing the incidence or treatment of dyskinesia [203, 205–207], but there is insufficient evidence to characterize them as unequivocally effective [41]. For example, a study on an animal model of PD demonstrated that continuous delivery of rotigotine did not induce dyskinesia and functional sensitization, whereas using an oral formulation at different intervals did [208]. On the other hand, a pilot study on duodenal infusion of L-DOPA was shown to induce similar levels of dyskinesia as pulsatile delivery systems; however, once dyskinesia are present, switching to duodenal L-DOPA reduces the duration of dyskinesia [209]. This highlights the variability in the effectiveness of these treatments. Furthermore, these approaches to dyskinesia treatment are limited due to the complexity of the procedure and the difficult long-term management of patients. Indeed, the invasive nature of some of these treatments limits the number of potential candidates; and the potential for severe complications requires adequate monitoring. Another option is to control dyskinesia by reducing the L-DOPA dose and introducing dopamine agonists. Again, this option is not without problems, including the lower efficacy of dopamine agonists in treating motor symptoms [210–213], as well as increasing the incidence of other disabling side effects such as somnolence, sleep attacks, dizziness, nausea, delusions, impulse control disorders, hallucinations and confusion [214, 215]. In addition, one must keep in mind that some studies have observed the appearance of dyskinesia with the use of dopamine agonists without the concomitant presence of L-DOPA [213].

There are currently very limited direct drug treatments for dyskinesia as only two medications were shown to be efficacious: amantadine and clozapine [41]. Amantadine is a NMDA receptor antagonist [216] that was shown to reduce significantly the duration and severity of dyskinesia in several studies [216–218]. However, its mechanism of action leading to reduction in dyskinesia has yet to be conclusively determined. Clozapine is a high affinity serotoninergic agonist as well as a low affinity dopamine agonist [219–221]. One study demonstrated the ability of clozapine to reduce dyskinesia significantly [222]. However, the severe side effects associated with clozapine, such as agranulocytosis [223], central nervous system depression, seizures, dementia, and myocarditis [224], limit its use in clinical practice as it requires strict monitoring.

Surgical interventions can also reduce dyskinesia in a subset of patients as both STN and GPi DBS were shown to reduce dyskinesia effectively [103, 109]. One possible mechanism behind the reduction in dyskinesia is reduction in medication dose following surgical treatment [225]. However, the end result is highly dependent on several factors such as lead placement, stimulation parameters and level of reduction in medications. Another surgical intervention that has demonstrated a reduction in dyskinesia is pallidotomy [73, 74, 226]. In fact, this intervention was shown to be as effective as STN DBS for the reduction of dyskinesia [74]. Again, the outcome of this procedure is greatly dependent on lesion extent and location.

Future avenues for drug treatment of dyskinesia include the development of adenosine A2A receptor antagonists [227, 228] as well as the use of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) antagonists [229] and orthosteric metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4) agonists [230]. While these compounds are currently in different testing phases, a few studies using adenosine A2A receptor antagonists and mGluR5 antagonists have demonstrated a significant reduction in dyskinesia induction in animal models [183, 186, 231] and subgroups of human samples [227, 229, 232]. On the other hand, orthosteric mGluR4 agonists are only beginning to be studied for their effect on the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia.

Maintaining therapeutic efficacy while at the same time trying to control dyskinesia can be difficult with all treatments for PD. Clinicians often progressively introduce an intricate combination of medications that could help re-establish neurotransmitter balance and avoid motor fluctuations. Unfortunately, the unavoidable dopaminergic denervation and receptor imbalances render this task increasingly difficult as the disease progresses.

How prominent is the problem of dyskinesia and its management?

The incidence of dyskinesia is estimated at 30% to 50% after five years of initiating L-DOPA treatment [142, 198]. As the disease progresses, the incidence can increase to 60% to 100% after 10 years [65, 198, 211, 233, 234]. These figures are even higher in young-onset PD where it is observed that almost all patients experience dyskinesia after only six years of treatment [22]. Once these motor fluctuations occur, increased monitoring of patients is required. However, the lack of movement disorders specialists able to handle such complex side effects of medication hinders proper monitoring of these patients. In the United States, the ratio of neurologists varies drastically between regions ranging from a low of 1 and a high of 11/100 000 population [235] with an average close to 5/100 000 population [236]. In Canada, in 2008, the number of neurologists varied between 0 and 3/100 000 population in different regions of a geographically vast country [237]. While most European countries fare relatively well with an average of 5 neurologists per 100 000 population [236], Asia, where the majority of the world's population resides and where the expected number of PD cases is expected to grow several fold in upcoming years [238], is in dire need of neurologists with less than 1/100 000 population [236]. Of note is that these figures encompass all neurologists; the number of movement disorders specialists, who possess the necessary tools to adequately manage the symptoms of PD and motor complications associated with their treatment, is much lower, and to our knowledge, has never been evaluated. Another issue facing patients with motor fluctuations is that most movement disorders specialists are located in larger cities; thus forcing patients from remote communities to travel great distances for medical consultations and follow-ups. These issues may explain why only 45% of patients with PD in Ontario (Canada) have access to a specialist at least once a year [239]. The lack of access to trained clinicians has a negative impact on patient care since constant management of medication is required to delay or negate the undesired motor fluctuations.

What would be the impact of better management of dyskinesia on quality of life?

The ability to engage and maintain social interactions is inevitably linked to the ability to interact with the physical environment and, as such, is associated on the level of independence of patients. In patients with PD, reduced participation in social activities appears in part related to loss of mobility and impairs quality of life [240, 241]. This phenomenon is later exacerbated due to disease progression and complications related to treatments [242, 243]. However, the actual impact of dyskinesia on quality of life is still controversial. Some researchers have suggested that dyskinesia have only a moderate impact on quality of life of patients [198, 244–246]. One study even observed an improvement in quality of life in PD patients with dyskinesia [244]. Another recent study demonstrated that 'Patients with PD experiencing dyskinesia are less likely to be concerned about dyskinesia and more likely to prefer dyskinesia over parkinsonian symptoms compared to patients without dyskinesia' [247]. This may be explained by the patient's own perspective on the impact of dyskinesia on his/her motor repertoire, that is, the movements a particular patient deems important for his/her quality of life. Of course, if dyskinesia have a moderate impact on the motor repertoire, it is likely that he/she will not consider dyskinesia as problematic. Patients would rather be able to perform their activities than be constricted by their parkinsonian symptoms. However, such findings must be interpreted carefully, in light of recent evidence showing that dyskinetic patients may suffer from anosognosia, that is unawareness of deficits associated with an illness [248]. Accordingly, even if they do not complain about their involuntary movements, dyskinesia may still have a deleterious effect on their motor repertoire. As such, mild dyskinesia themselves may not be problematic, but more severe forms may reduce quality of life by impacting on the patients' motor repertoire.

In fact, other studies showed that the presence of dyskinesia is a key factor in determining the quality of life of patients [249–251], especially in young patients who participate in the workforce. Studies showed that the main dimensions of quality of life that are affected by dyskinesia are psychological, social [252, 253] and stigma [253–255]. This may be the result of loss in mobility, increased falls [256], weight loss [156] and even modifications of motor behavior in the OFF state [257]. Other studies demonstrated that the reduction in quality of life of PD patients with dyskinesia [258–260] could also be a result of higher levels of anxiety [261–264] and depression[260], more so than in patients without dyskinesia. However, in the study of Montel et al. [253], the only factor that had a significant impact on quality of life was the presence of dyskinesia, not neuropsychiatric manifestations. This indicates that dyskinesia can affect patient quality of life directly and also by inducing, or at least modulating the level of different neuropsychiatric disorders.

The impact of dyskinesia on the quality of life of PD patients can also be evaluated by assessing the effectiveness of interventions aimed at controlling dyskinesia on quality of life. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that PD patients had a significant improvement in quality of life after 18 months of continuous intra-duodenal L-DOPA infusion [265]. Interestingly, they did not observe a significant change in 'ON medication' motor symptomatology after treatment but did observe a significant reduction in dyskinesia. As such, the reduction in dyskinesia may have played a role in the improvement of quality of life. Similar results were obtained in patients undergoing GPi DBS where the reduction in dyskinesia scores was highly correlated with the improvement in overall quality of life [266]. While these are merely two examples of studies using quality of life as primary or secondary endpoints to assess the impact of different interventions, it is becoming more common to use quality of life to evaluate therapeutic effectiveness.

Another issue to consider is that dyskinesia also impact upon on the quality of life of patients' primary caregivers (for example, spouses). Indeed, as the disease progresses and patients with PD begin dealing with a loss of independence, the quality of life of their caregiver also degrades as they are more prone to social isolation, psychological problems, such as depression, and physical issues [267–270]. This is evident through the results of McCabe et al. [271] where PD patients and caregivers only differed in physical- and psychological-related quality of life. Social interaction and environmental quality of life scores were not significantly different [271]. These issues become more prominent with disease progression when motor complications, such as dyskinesia, are apparent [272]. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that psychosocial factors such as social support are critically important to the caregivers' quality of life [273]. As health-care systems are over-extended and promote the implementation of community care programs as a means of alleviating pressure on the system, the capacity of caregivers to provide support becomes essential [274]. If caregiver burden is excessive, it may reduce the quality of the care patients require [273]. As such, it is important to acknowledge and find ways to optimize the caregivers' quality of life.

What would be the impact of better management of dyskinesia on the health-care system?

As the disease progresses, so does the burden on patients and the health community [83, 275]. Studies have demonstrated the immense effect of dyskinesia on the costs of treating PD patients. For instance, a European study showed that the average cost per annum for the treatment of PD patients without dyskinesia was €11,412, but it more than doubled to €24,990 in patients with severe dyskinesia [260]. This increase in treatment cost was accounted for by both non-medical expenditures, such as community services and unpaid help provided by the caregiver, and medical expenditures related to medication and hospitalization due to more complex and expensive treatment regimens [260]. A French study also demonstrated that the presence of dyskinesia more than doubled treatment costs and increased medical visits [276]. They also observed that the severity of dyskinesia increased medical costs by increasing the need for caregivers. This led them to estimate the total annual medical cost of dyskinesia in France to be between 588 and 812 million francs [276]. Furthermore, a recent study from the United States showed that dyskinesia resulted in an increase in total treatment costs by 29%, and PD-related treatment costs by 78% compared to costs incurred by PD patients without dyskinesia [277]. This translates into an increase of $5,549 in the year following the first appearance of dyskinesia when compared to PD patients without dyskinesia. The majority of this amount was related to an increase in PD-related costs of $4,456 in patients with dyskinesia; not to costs associated with co-mobidities [277].

A major problem is that these direct costs have to be added to the already increased health-related expenditures associated with having PD compared to healthy aging [278]. In Canada, the annual direct costs related to PD were estimated at $202 million, which includes hospital (44%), drugs (49%) and physician consultations (7%). Indirect costs associated with mortality (38%) and morbidity (62%) were estimated at $245 million, for a total of approximately $447 million [278]. Interestingly, a great proportion of indirect costs are related to early retirement. The direct health-care cost of PD in the United States was estimated at $10,349 per patient per year [279]. Combining these direct costs with estimates of indirect costs, the total costs of PD in the United States may be as high as $23 billion annually [279]. If we consider that the number of persons 65 years of age and older is expected to increase significantly over the upcoming years, the cost of treating PD patients is likely to exceed $50 billion annually in the United States by 2040 [279]. In China, the problem is even greater because of the larger number of patients. In 2004, it was estimated that the yearly health-care cost was about $925 per patient, which represents half of the mean individual annual income [280], for a total of $1.57 billion annually. The total cost correlated significantly with disease severity and the frequency of outpatient visits [280]. It is clear that better patient management is required and one approach is to develop and implement evidence-based practice. The question then becomes if the reduction of dyskinesia incidence and severity can modulate the costs. A recent study examined the effectiveness (time to levodopa and time to levodopa-induced dyskinesia), cost, and quality-adjusted life-years in two trials of dopamine agonists. They showed that rasagiline delayed the onset of dyskinesia by 10% and reduced costs by 18% per patient over five years [281]. Furthermore, a French study estimated that each 10% of reduction in OFF periods would result in a 5% reduction of direct medical costs [282]. These studies demonstrate that finding approaches to control either the incidence or the severity of dyskinesia and other motor fluctuations should be developed and implemented in order to reduce the burden on the health-care system.

What is the theory behind our proposed approach to the treatment of dyskinesia?

Evidence-based practice aims to apply the best available evidence from scientific investigations to clinical decision making. To apply evidence-based practice for the management of dyskinesia, information about the influence of dyskinesia on voluntary movements must be known so as to understand the challenges facing patients when planning and executing movements from their motor repertoire. It is important to discriminate between activities of daily living and motor repertoire of patients as activities of daily living are essential for minimal functional independence while the motor repertoire encompasses all movements deemed important for a good quality of life for a specific patient. As such, the motor repertoire will be personalized and will vary greatly depending on the movements patients wish to perform on a regular basis. Finally, it is important to assess whether other symptoms are concomitantly present with dyskinesia; which may in fact be responsible for motor deficits. To date, several algorithms have been proposed to manage dyskinesia [283, 284]. Interestingly, these algorithms are geared towards markedly reducing or eliminating dyskinesia, without necessarily taking into account how the proposed strategy affects the motor repertoire of patients. This is important since some patients may rather have mild dyskinesia then undergo the process of medication change, especially if dyskinesia do not hinder their motor repertoire. Indeed, the reduction in dyskinesia through either a reduction in medication dosage or a change in medication could lead to a resurgence of typical hypo- or hyper-kinetic parkinsonian symptoms impeding the patient's voluntary motor behaviors and hence reduce his quality of life for that specific period. The clinician will judge whether the reduction in dyskinesia following treatment regimen modification based on these algorithms is clinically satisfactory. For this, clinicians rely mostly on their experience and patient feedback. They can also use clinical scales [285–288] to assess the amplitude of dyskinesia and their impact on activities of daily living. However, current scales only provide a general sense of the amplitude of dyskinesia and their impact. Most do not measure the impact of the amplitude of dyskinesia on voluntary movements and certainly not on the entire motor repertoire of patients. In fact, a recent review of the different scales for the assessment of dyskinesia found that of the eight scales used in PD, only two were recommended for use (that is, the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), and the Rush Dyskinesia scale) [288]. The AIMS assesses the amplitude of dyskinesia in each limb whereas the Rush also incorporates a section on the impact of dyskinesia on certain activities of daily living such as putting on a coat. A recent scale, the PDYS-26, a patient-based questionnaire, focuses solely on the impact of dyskinesia on activities of daily living [289]. One main issue of these scales is that they cannot segregate the impact of dyskinesia and cardinal symptoms of PD on the performance of motor behaviors. Another point that requires attention is that, as mentioned above, activities of daily living do not circumscribe the whole motor repertoire deemed necessary by each patient; they merely represent general tasks that provide some functional independence. For example, a patient who is an artist painter with low amplitude dyskinesia may deem that his/her dyskinesia are devastating, while most daily living activities are actually intact (that is, he can put on a coat, cut his food and dress himself but, he cannot perform the fine voluntary movements required for him to paint a canvas). Then, one could legitimately ask the following question: how does the amplitude of dyskinesia relate to its impact on voluntary movements performed in daily life? The opposite could also be true. A patient with high levels of dyskinesia may judge that his/her involuntary movements are not an issue since they prefer to be dyskinetic rather than OFF, as proposed in a recent paper [247].

We propose that the evaluation of the impact of dyskinesia be viewed as a function of a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The concept of the SNR is based on the fact that success of voluntary movements (the motor output) is directly correlated to the magnitude of the intended voluntary movement (the signal) and inversely correlated with the magnitude of the involuntary movement (the noise) in the motor stream [290–297]. In other words, the likelihood of success in performing voluntary movements is not only dependent on the magnitude of the symptoms present, but also dependent on the type of movement performed by the patients. Such an analysis would make it possible to determine the motor repertoire available to patients based on the magnitude of symptoms. For instance, if a patient presents only with tremor, the SNR could be represented by equation 1:

Here, tremor would become deleterious only if the intended movement is below a threshold that will allow tremor to be close to, or supersede, the voluntary movement in amplitude. It could also be deleterious if the frequency of the intended movement is close to the frequency of that tremor [298–300]. Of course, this is an oversimplification as PD patients rarely exhibit only one motor symptom. Therefore, a more accurate representation of the SNR observed in PD patients would be equation 2:

Here, the noise would be the sum of all cardinal motor symptoms, regardless of their neural origin. Indeed, bradykinesia could be caused by bradyphrenia during complex decision making, rather than a lack of cortical activation by thalamo-cortical pathways. Interestingly, as the disease progresses and motor complications arise, more 'noise' parameters could be added to equation 2 such that dyskinesia could be taken into account (equation 3):

Success for a particular task would be predicated upon the ratio between the amplitude of the intended movement (the signal; the numerator) and the magnitude of symptoms (noise; the denominator) (see Figure 1).

This relationship between voluntary and involuntary movements was demonstrated by us in previous work [290–297]. For instance, we showed that during slow alternating movements at the wrist, tremor was detected [295], and its amplitude was directly correlated with deficits of accuracy [294]. During fast movement, tremor was undetected, and its amplitude previously assessed in the postural condition was unrelated to performance [294, 297]. Furthermore, we showed that ventro-lateral thalamotomy [59, 61, 294] had no impact on fast movements, but increased the SNR by removing tremor, hence improving tremendously the accuracy during slow movements [294]. We also showed that in tasks where the voluntary movement was performed with varying amplitude and velocity, the faster sections presented with higher SNR, and there was a reduction in deviation from the intended trajectory of the movement [294, 295]. Accordingly, the amplitude of velocity of the intended movement seemed to be important in determining the impact of involuntary movements on voluntary motor acts. This concept relates to Fitts law [301], which proposes that two movements having the same amplitude may possess different velocity profiles, depending on the difficulty (target size) of the task. For example, bringing a glass of water to the mouth may have the same amplitude as bringing a spoon full of soup, but the velocity will not be the same because of the increased difficulty associated with keeping the soup in the spoon. As such, in order to properly assess the complexity of a voluntary movement, both its amplitude and velocity must be examined. In patients where whole-body peak-dose dyskinesia were recorded simultaneously with voluntary movements (same tasks as above), we found that during fast hand movements, dyskinesia were not visible [296]. Interestingly, patients with dyskinesia presented with levels of bradykinesia similar to those of PD patients without dyskinesia [296]. We also found no relationship between the level of dyskinesia and accuracy during slow movements [293], indicating that dyskinesia may not have been the primary source of error during movements that required accuracy. This strongly supports the concept that 'noise' is not limited to visible involuntary movements, but may also include other symptoms such as rigidity or bradykinesia [291] as proposed in equations 2 and 3. In the aforementioned study, patients had little or no clinically-detectable rigidity, so bradykinesia was probably the main cause of reduction in motor performance. Taken together, this illustrates that different types of noise observed in PD can be independent from each other at the neurophysiological level but can each contribute to the performance of a given task. In another study, we demonstrated that patients with Huntington's disease presenting with chorea were not impaired during fast hand movements. However, they presented with large errors during slow manual tracking, which correlated with the amplitude of chorea. This illustrates again that involuntary movements can be of no consequence when the SNR is large enough. This also indicates that the SNR concept could be applied to pathologies other than PD.

The aforementioned data on PD fits well with issues facing clinicians. Indeed, any reduction in dyskinesia levels could lead to increased typical parkinsonian motor symptoms. Accordingly, clinicians may be replacing one kind of noise with another one (this concept is illustrated in Figure 2).

Two examples to illustrate opposite results following drug regimen change. In situation 1, a change in drug regimen decreased dyskinesia amplitude which then led to increased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (dark grey lines), and consequently increased motor repertoire. In situation 2, the same change in drug regimen also led to a reduction of dyskinesia amplitude. However, there is resurgence of typical motor symptoms associated with PD, thus increasing the noise, which will induce a decrease of overall SNR, hence a reduction in the motor repertoire (light grey lines). Here, the patient did not benefit from the reduction of dyskinesia, as his/her motor repertoire worsened. These examples illustrate the challenges faced by clinicians when managing dyskinesia. PD, Parkinson's disease.

To better illustrate this theory, we present below two hypothetical situations that could be encountered in clinical practice (Figure 2).

Situation 1: the clinician reduces L-DOPA or dopamine agonist dosage and the level of dyskinesia is reduced. This results in an increased motor repertoire because of the increased SNR. Dyskinesia management is effective and should be pursued.

Situation 2: the clinician reduces medication dosage and the level of dyskinesia is reduced, but leads to a reduction in motor repertoire. As such, the dyskinesia portion of the noise is reduced but is accompanied by an increase in noise associated with typical parkinsonian symptoms present when medication is lacking, such as bradykinesia or rigidity. Here, the treatment regimen should be modified until situation 1 is achieved. If situation 1 cannot be achieved, it may be that having some dyskinesia is the preferred solution since the motor repertoire is greater with dyskinesia, as discussed by our group [293, 296] and others [302]. Surgery may be considered as an alternative in this case because, as mentioned above, it may control dyskinesia possibly through a reduction in medication. The aforementioned approach would seem logical to movement disorders specialists, but may be more difficult to implement by less experienced clinicians treating patients with PD experiencing motor fluctuations.

Accordingly, we propose that there is a SNR related to dyskinesia below which the execution of a voluntary movement is rendered impossible (or not functionally possible). Whether this SNR is systematic across patients or specific to each patient is currently under investigation in our laboratory. We also propose that a reduction of dyskinesia amplitude through a proper medication regimen modification will result in an increased motor repertoire only if typical parkinsonian symptoms do not re-emerge to levels affecting significantly the SNR for specific tasks.

How may this strategy be translated into clinical practice?

We propose that clinicians may be able to view treatment success as an optimization of each patient's motor repertoire, rather than simply targeting symptomatology. Highly-trained movement disorders specialists probably use such an approach intuitively, but it is the lack of tools to help clinicians less experienced in dealing with PD patients that should be addressed. For instance, the presence of dyskinesia should be deemed detrimental if it significantly impacts the SNR and thus the motor repertoire of each patient. Based on the aforementioned evidence, there is a need to develop clinical evaluation protocols that specifically assess the motor repertoire of patients. Such a tool must reflect the wide range of movements performed during everyday life activities, it must incorporate a customizable section and be easy to perform, as well as give clinicians the ability to follow the progression within patients and compare the results between patients. While acknowledging that current clinical scales for the evaluation of dyskinesia provide invaluable information regarding their amplitude and impact on some activities of daily living, they lack the specificity for evaluating the range of the motor repertoire accessible to patients. We understand the immense difficulties associated with the development of a clinical scale of this type but, using such an evaluation, the clinician would be in a better position to determine whether the intervention was helpful to the patient, regardless of its effect on symptomatology. We are currently in the process of assessing the motor repertoire of patients without dyskinesia and with different levels of dyskinesia in order to develop a model of interaction between symptomatology and motor behaviors. Once this relationship is known, the development of such a tool could be envisioned.

Summary

The treatment of PD requires the evaluation of several motor symptoms affecting the quality of life of patients. The limited number of movement disorders specialists and the increasing number of patients with PD places a toll on health-care systems world-wide. The need to develop and implement evidence-based medicine is urgent. In this review, we proposed a novel way to view the clinical management of motor symptoms in PD and more specifically of dyskinesia. While we acknowledge that this view requires further testing, we believe that systematizing the approach to the treatment of motor symptoms in PD will lead to an improvement in patient quality of life and, hopefully, a relief on our health-care system.

Abbreviations

- AIMS:

-

Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale

- AMPA:

-

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- CDD:

-

continuous drug delivery

- CM/pF:

-

centro-median-parafascicular complex

- COMT:

-

catechol-O-methyl tttransferase

- DBS:

-

deep brain stimulation

- GPi:

-

globus pallidus internus

- L-DOPA:

-

L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine

- MAO-B:

-

monoamine oxydase B

- mGluR4:

-

metabotropic glutamate receptor 4

- mGluR5:

-

metabotropic glutamate receptor 5

- NMDA:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PD:

-

Parkinson's disease

- PPN:

-

pedonculopontine nucleus

- SNR:

-

signal-to-noise ratio

- STN:

-

subthalamic nucleus

- VL thalamus:

-

ventrolateral thalamus.

References

Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O: [Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system]. Klin Wochenschr. 1960, 38: 1236-1239.

Jankovic J: Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008, 79 (4): 368-376.

Zgaljardic DJ, Foldi NS, Borod JC: Cognitive and behavioral dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: neurochemical and clinicopathological contributions. J Neural Transm. 2004, 111: 1287-1301.

Gallagher DA, Schrag A: Psychosis, apathy, depression and anxiety in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2012, 46: 581-589.

Gagnon JF, Postuma RB, Mazza S, Doyon J, Montplaisir J: Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5: 424-432.

Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Vendette M, Charland K, Montplaisir J: Manifestations of Parkinson disease differ in association with REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2008, 23: 1665-1672.

Tan LC: Mood disorders in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012, 18 (Suppl 1): S74-76.

Hemmerle AM, Herman JP, Seroogy KB: Stress, depression and Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2012, 233: 79-86.

Peavy GM: Mild cognitive deficits in Parkinson disease: where there is bradykinesia, there is bradyphrenia. Neurology. 2010, 75: 1038-1039.

Perez Trullen JM, Modrego Pardo PJ, Vazquez Andre ML: Bradyphrenia and parkinsonism. Age Ageing. 1994, 23: 524.

Rogers D: Bradyphrenia in parkinsonism: a historical review. Psychol Med. 1986, 16: 257-265.

Rogers D: Bradyphrenia in Parkinson's disease. Br J Hosp Med. 1988, 39: 128-130.

Doty RL: Olfaction in Parkinson's disease and related disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2012, 46: 527-552.

Del Sorbo F, Albanese A: Clinical management of pain and fatigue in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012, 18 (Suppl 1): S233-236.

de Rijk MC, Breteler MM, Graveland GA, Ott A, Grobbee DE, van der Meche FG, Hofman A: Prevalence of Parkinson's disease in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1995, 45: 2143-2146.

de Rijk MC, Launer LJ, Berger K, Breteler MM, Dartigues JF, Baldereschi M, Fratiglioni L, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage J, Trenkwalder C, Hofman A: Prevalence of Parkinson's disease in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology. 2000, 54 (Suppl 5): S21-23.

de Rijk MC, Tzourio C, Breteler MM, Dartigues JF, Amaducci L, Lopez-Pousa S, Manubens-Bertran JM, Alperovitch A, Rocca WA: Prevalence of parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease in Europe: the EUROPARKINSON Collaborative Study. European Community Concerted Action on the Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997, 62: 10-15.

Li SC, Schoenberg BS, Wang CC, Cheng XM, Rui DY, Bolis CL, Schoenberg DG: A prevalence survey of Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders in the People's Republic of China. Arch Neurol. 1985, 42: 655-657.

Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Quinn NP: Cross sectional prevalence survey of idiopathic Parkinson's disease and Parkinsonism in London. BMJ. 2000, 321: 21-22.

de Lau LM, Giesbergen PC, de Rijk MC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM: Incidence of parkinsonism and Parkinson disease in a general population: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2004, 63: 1240-1244.

Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Bernstein AL, Fross RD, Leimpeter A, Bloch DA, Nelson LM: Incidence of Parkinson's disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 157: 1015-1022.

Quinn N, Critchley P, Marsden CD: Young onset Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 1987, 2: 73-91.

Morris ME: Movement disorders in people with Parkinson disease: a model for physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2000, 80: 578-597.

Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ: Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992, 55: 181-184.

Diamond SG, Markham CH, Hoehn MM, McDowell FH, Muenter MD: Effect of age at onset on progression and mortality in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1989, 39: 1187-1190.

Harada H, Nishikawa S, Takahashi K: Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease in a Japanese city. Arch Neurol. 1983, 40: 151-154.

Barbeau A, Pourcher E: New data on the genetics of Parkinson's disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1982, 9: 53-60.

Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Brown R, Marsden CD, Quinn N: Young-onset Parkinson's disease revisited--clinical features, natural history, and mortality. Mov Disord. 1998, 13: 885-894.

Parkinson Study Group: A controlled trial of rasagiline in early Parkinson disease: the TEMPO Study. Arch Neurol. 2002, 59: 1937-1943.

Kurlan R, Rubin AJ, Miller C, Rivera-Calimlim L, Clarke A, Shoulson I: Duodenal delivery of levodopa for on-off fluctuations in parkinsonism: preliminary observations. Ann Neurol. 1986, 20: 262-265.

Gibb WR, Lees AJ: A comparison of clinical and pathological features of young- and old-onset Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1988, 38: 1402-1406.

Pederzoli M, Girotti F, Scigliano G, Aiello G, Carella F, Caraceni T: L-DOPA long-term treatment in Parkinson's disease: age-related side effects. Neurology. 1983, 33: 1518-1522.

Ishihara LS, Cheesbrough A, Brayne C, Schrag A: Estimated life expectancy of Parkinson's patients compared with the UK population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007, 78: 1304-1309.

Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, Quinn N, Jahanshahi M: Young- versus older-onset Parkinson's disease: impact of disease and psychosocial consequences. Mov Disord. 2003, 18: 1250-1256.

Kostic V, Przedborski S, Flaster E, Sternic N: Early development of levodopa-induced dyskinesias and response fluctuations in young-onset Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1991, 41: 202-205.

Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB: The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989, 12: 366-375.

Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL: Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986, 9: 357-381.

Crossman AR: Primate models of dyskinesia: the experimental approach to the study of basal ganglia-related involuntary movement disorders. Neuroscience. 1987, 21: 1-40.

Alexander GE, Crutcher MD: Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990, 13: 266-271.

Kravitz AV, Freeze BS, Parker PR, Kay K, Thwin MT, Deisseroth K, Kreitzer AC: Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature. 2010, 466: 622-626.

Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, Ravina B, Seppi K, Coelho M, Poewe W, Rascol O, Goetz CG, Sampaio C: The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011, 26 (Suppl 3): S2-41.

Cenci MA, Ohlin KE, Odin P: Current options and future possibilities for the treatment of dyskinesia and motor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011, 10: 670-684.

Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O: [The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1961, 73: 787-788.

Fahn S: The history of dopamine and levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008, 23 (Suppl 3): S497-508.

Barbeau A, Murphy GF, Sourkes TL: Excretion of dopamine in diseases of basal ganglia. Science. 1961, 133: 1706-1707.

Stern MB, Marek KL, Friedman J, Hauser RA, LeWitt PA, Tarsy D, Olanow CW: Double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of rasagiline as monotherapy in early Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord. 2004, 19: 916-923.

Nutt JG, Fellman JH: Pharmacokinetics of levodopa. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1984, 7: 35-49.

Bianchine JR, Messiha FS, Hsu TH: Peripheral aromatic L-amino acids decarboxylase inhibitor in parkinsonism. II. Effect on metabolism of L-2- 14 C-dopa. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972, 13: 584-594.

Kuruma I, Bartholini G, Tissot R, Fletscher A: Comparative investigation of inhibitors of extracerebral dopa decarboxylase in man and rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1972, 24: 289-294.

Contin M, Riva R, Albani F, Baruzzi A: Pharmacokinetic optimisation in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996, 30: 463-481.

Nyholm D: Pharmacokinetic optimisation in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006, 45: 109-136.

Riederer P, Youdim MB: Monoamine oxidase activity and monoamine metabolism in brains of parkinsonian patients treated with l-deprenyl. J Neurochem. 1986, 46: 1359-1365.

Effect of deprenyl on the progression of disability in early Parkinson's disease. The Parkinson Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321: 1364-1371.

Palhagen S, Heinonen EH, Hagglund J, Kaugesaar T, Kontants H, Maki-Ikola O, Palm R, Turunen J: Selegiline delays the onset of disability in de novo parkinsonian patients. Swedish Parkinson Study Group. Neurology. 1998, 51: 520-525.

Seppi K, Weintraub D, Coelho M, Perez-Lloret S, Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Hametner EM, Poewe W, Rascol O, Goetz CG, Sampaio C: The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: treatments for the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011, 26 (Suppl 3): S42-80.

Watts RL: The role of dopamine agonists in early Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1997, 49 (Suppl 1): S34-48.

Olanow CW: The role of dopamine agonists in the treatment of early Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2002, 58 (Suppl 1): S33-41.

Scott RM, Brody JA, Cooper IS: The effect of thalamotomy on the progress of unilateral Parkinson's disease. J Neurosurg. 1970, 32: 286-288.

Duval C, Panisset M, Bertrand G, Sadikot AF: Evidence that ventrolateral thalamotomy may eliminate the supraspinal component of both pathological and physiological tremors. Exp Brain Res. 2000, 132: 216-222.

Duval C, Panisset M, Strafella AP, Sadikot AF: The impact of ventrolateral thalamotomy on tremor and voluntary motor behavior in patients with Parkinson's disease. Exp Brain Res. 2006, 170: 160-171.

Duval C, Strafella AP, Sadikot AF: The impact of ventrolateral thalamotomy on high-frequency components of tremor. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005, 116: 1391-1399.

Atkinson JD, Collins DL, Bertrand G, Peters TM, Pike GB, Sadikot AF: Optimal location of thalamotomy lesions for tremor associated with Parkinson disease: a probabilistic analysis based on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging and an integrated digital atlas. J Neurosurg. 2002, 96: 854-866.

Ohye C, Higuchi Y, Shibazaki T, Hashimoto T, Koyama T, Hirai T, Matsuda S, Serizawa T, Hori T, Hayashi M, Ochiai T, Samura H, Yamashiro K: Gamma knife thalamotomy for Parkinson disease and essential tremor: a prospective multicenter study. Neurosurgery. 2012, 70: 526-535. discussion 535-526

Fox MW, Ahlskog JE, Kelly PJ: Stereotactic ventrolateralis thalamotomy for medically refractory tremor in post-levodopa era Parkinson's disease patients. J Neurosurg. 1991, 75: 723-730.

Hurtig HI, Stern MB: Thalamotomy for Parkinson's disease. J Neurosurg. 1985, 62: 163-165.

Matsumoto K, Shichijo F, Fukami T: Long-term follow-up review of cases of Parkinson's disease after unilateral or bilateral thalamotomy. J Neurosurg. 1984, 60: 1033-1044.

Mosso JA, Rand RW: Management of parkinson's disease--combined therapy with levodopa and thalamotomy. West J Med. 1975, 122: 1-6.

Tasker RR, Munz M, Junn FS, Kiss ZH, Davis K, Dostrovsky JO, Lozano AM: Deep brain stimulation and thalamotomy for tremor compared. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1997, 68: 49-53.

Tasker RR, Siqueira J, Hawrylyshyn P, Organ LW: What happened to VIM thalamotomy for Parkinson's disease?. Appl Neurophysiol. 1983, 46: 68-83.

de Bie RM, de Haan RJ, Schuurman PR, Esselink RA, Bosch DA, Speelman JD: Morbidity and mortality following pallidotomy in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Neurology. 2002, 58: 1008-1012.

De Bie RM, Schuurman PR, Esselink RA, Bosch DA, Speelman JD: Bilateral pallidotomy in Parkinson's disease: a retrospective study. Mov Disord. 2002, 17: 533-538.

Esselink RA, de Bie RM, de Haan RJ, Lenders MW, Nijssen PC, Staal MJ, Smeding HM, Schuurman PR, Bosch DA, Speelman JD: Unilateral pallidotomy versus bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in PD: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2004, 62: 201-207.

Esselink RA, de Bie RM, de Haan RJ, Lenders MW, Nijssen PC, van Laar T, Schuurman PR, Bosch DA, Speelman JD: Long-term superiority of subthalamic nucleus stimulation over pallidotomy in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009, 73: 151-153.

Esselink RA, de Bie RM, de Haan RJ, Steur EN, Beute GN, Portman AT, Schuurman PR, Bosch DA, Speelman JD: Unilateral pallidotomy versus bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson's disease: one year follow-up of a randomised observer-blind multi centre trial. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006, 148: 1247-1255. discussion 1255

Smeding HM, Esselink RA, Schmand B, Koning-Haanstra M, Nijhuis I, Wijnalda EM, Speelman JD: Unilateral pallidotomy versus bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in PD--a comparison of neuropsychological effects. J Neurol. 2005, 252: 176-182.

Coban A, Hanagasi HA, Karamursel S, Barlas O: Comparison of unilateral pallidotomy and subthalamotomy findings in advanced idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Br J Neurosurg. 2009, 23: 23-29.

Bronstein JM, DeSalles A, DeLong MR: Stereotactic pallidotomy in the treatment of Parkinson disease: an expert opinion. Arch Neurol. 1999, 56: 1064-1069.

Gironell A, Kulisevsky J, Rami L, Fortuny N, Garcia-Sanchez C, Pascual-Sedano B: Effects of pallidotomy and bilateral subthalamic stimulation on cognitive function in Parkinson disease. A controlled comparative study. J Neurol. 2003, 250: 917-923.

Hariz MI, Bergenheim AT: A 10-year follow-up review of patients who underwent Leksell's posteroventral pallidotomy for Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2001, 94: 552-558.

Intemann PM, Masterman D, Subramanian I, DeSalles A, Behnke E, Frysinger R, Bronstein JM: Staged bilateral pallidotomy for treatment of Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2001, 94: 437-444.

Alvarez L, Macias R, Pavon N, Lopez G, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Rodriguez R, Alvarez M, Pedroso I, Teijeiro J, Fernandez R, Casabona E, Salazar S, Maragoto C, Carballo M, García I, Guridi J, Juncos JL, DeLong MR, Obeso JA: Therapeutic efficacy of unilateral subthalamotomy in Parkinson's disease: results in 89 patients followed for up to 36 months. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009, 80: 979-985.

Merello M, Tenca E, Perez Lloret S, Martin ME, Bruno V, Cavanagh S, Antico J, Cerquetti D, Leiguarda R: Prospective randomized 1-year follow-up comparison of bilateral subthalamotomy versus bilateral subthalamic stimulation and the combination of both in Parkinson's disease patients: a pilot study. Br J Neurosurg. 2008, 22: 415-422.

Alvarez L, Macias R, Lopez G, Alvarez E, Pavon N, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Juncos JL, Maragoto C, Guridi J, Litvan I, Tolosa ES, Koller W, Vitek J, DeLong MR, Obeso JA: Bilateral subthalamotomy in Parkinson's disease: initial and long-term response. Brain. 2005, 128: 570-583.

Gill SS, Heywood P: Bilateral dorsolateral subthalamotomy for advanced Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 1997, 350: 1224.

Obeso JA, Jahanshahi M, Alvarez L, Macias R, Pedroso I, Wilkinson L, Pavon N, Day B, Pinto S, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Tejeiro J, Artieda J, Talelli P, Swayne O, Rodríguez R, Bhatia K, Rodriguez-Diaz M, Lopez G, Guridi J, Rothwell JC: What can man do without basal ganglia motor output? The effect of combined unilateral subthalamotomy and pallidotomy in a patient with Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2009, 220: 283-292.

Patel NK, Heywood P, O'Sullivan K, McCarter R, Love S, Gill SS: Unilateral subthalamotomy in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2003, 126: 1136-1145.

Su PC, Tseng HM: Subthalamotomy for end-stage severe Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002, 17: 625-627. author reply 627

Su PC, Tseng HM, Liu HM, Yen RF, Liou HH: Subthalamotomy for advanced Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2002, 97: 598-606.

Su PC, Tseng HM, Liu HM, Yen RF, Liou HH: Treatment of advanced Parkinson's disease by subthalamotomy: one-year results. Mov Disord. 2003, 18: 531-538.

Tseng HM, Su PC, Liu HM, Liou HH, Yen RF: Bilateral subthalamotomy for advanced Parkinson disease. Surg Neurol. 2007, 68 (Suppl 1): S43-50. discussion S50-41

Ponce FA, Lozano AM: Deep brain stimulation state of the art and novel stimulation targets. Prog Brain Res. 2010, 184: 311-324.

Videnovic A, Metman LV: Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: prevalence of adverse events and need for standardized reporting. Mov Disord. 2008, 23: 343-349.

Seijo FJ, Alvarez-Vega MA, Gutierrez JC, Fdez-Glez F, Lozano B: Complications in subthalamic nucleus stimulation surgery for treatment of Parkinson's disease. Review of 272 procedures. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007, 149: 867-875. discussion 876

Hu X, Jiang X, Zhou X, Liang J, Wang L, Cao Y, Liu J, Jin A, Yang P: Avoidance and management of surgical and hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2010, 88: 296-303.

Bronstein JM, Tagliati M, Alterman RL, Lozano AM, Volkmann J, Stefani A, Horak FB, Okun MS, Foote KD, Krack P, Pahwa R, Henderson JM, Hariz MI, Bakay RA, Rezai A, Marks WJ, Moro E, Vitek JL, Weaver FM, Gross RE, DeLong MR: Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: an expert consensus and review of key issues. Arch Neurol. 2011, 68: 165.

Lanotte M, Verna G, Panciani PP, Taveggia A, Zibetti M, Lopiano L, Ducati A: Management of skin erosion following deep brain stimulation. Neurosurg Rev. 2009, 32: 111-114. discussion 114-115

Lyons KE, Wilkinson SB, Overman J, Pahwa R: Surgical and hardware complications of subthalamic stimulation: a series of 160 procedures. Neurology. 2004, 63: 612-616.

Hariz MI, Rehncrona S, Quinn NP, Speelman JD, Wensing C: Multicenter study on deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease: an independent assessment of reported adverse events at 4 years. Mov Disord. 2008, 23: 416-421.

Follett KA, Torres-Russotto D: Deep brain stimulation of globus pallidus interna, subthalamic nucleus, and pedunculopontine nucleus for Parkinson's disease: which target?. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012, 18 (Suppl 1): S165-167.

Weaver FM, Follett KA, Stern M, Luo P, Harris CL, Hur K, Marks WJ, Rothlind J, Sagher O, Moy C, Pahwa R, Burchiel K, Hogarth P, Lai EC, Duda JE, Holloway K, Samii A, Horn S, Bronstein JM, Stoner G, Starr PA, Simpson R, Baltuch G, De Salles A, Huang GD, Reda DJ, CSP 468 Study Group: Randomized trial of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: thirty-six-month outcomes. Neurology. 2012, 79: 55-65.

Gervais-Bernard H, Xie-Brustolin J, Mertens P, Polo G, Klinger H, Adamec D, Broussolle E, Thobois S: Bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in advanced Parkinson's disease: five year follow-up. J Neurol. 2009, 256: 225-233.

Kleiner-Fisman G, Herzog J, Fisman DN, Tamma F, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Lang AE, Deuschl G: Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: summary and meta-analysis of outcomes. Mov Disord. 2006, 21 (Suppl 14): S290-304.

Follett KA, Weaver FM, Stern M, Hur K, Harris CL, Luo P, Marks WJ, Rothlind J, Sagher O, Moy C, Pahwa R, Burchiel K, Hogarth P, Lai EC, Duda JE, Holloway K, Samii A, Horn S, Bronstein JM, Stoner G, Starr PA, Simpson R, Baltuch G, De Salles A, Huang GD, Reda DJ, CSP 468 Study Group: Pallidal versus subthalamic deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010, 362: 2077-2091.

Odekerken VJ, van Laar T, Staal MJ, Mosch A, Hoffmann CF, Nijssen PC, Beute GN, van Vugt JP, Lenders MW, Contarino MF, Mink MS, Bour LJ, van den Munckhof P, Schmand BA, de Haan RJ, Schuurman PR, de Bie RM: Subthalamic nucleus versus globus pallidus bilateral deep brain stimulation for advanced Parkinson's disease (NSTAPS study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12: 37-55.

Okun MS, Foote KD: Parkinson's disease DBS: what, when, who and why? The time has come to tailor DBS targets. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010, 10: 1847-1857.

Taba HA, Wu SS, Foote KD, Hass CJ, Fernandez HH, Malaty IA, Rodriguez RL, Dai Y, Zeilman PR, Jacobson CE, Okun MS: A closer look at unilateral versus bilateral deep brain stimulation: results of the National Institutes of Health COMPARE cohort. J Neurosurg. 2010, 113: 1224-1229.

Moro E, Lozano AM, Pollak P, Agid Y, Rehncrona S, Volkmann J, Kulisevsky J, Obeso JA, Albanese A, Hariz MI, Quinn NP, Speelman JD, Benabid AL, Fraix V, Mendes A, Welter ML, Houeto JL, Cornu P, Dormont D, Tornqvist AL, Ekberg R, Schnitzler A, Timmermann L, Wojtecki L, Gironell A, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Guridi J, Bentivoglio AR, Contarino MF, Romito L, et al: Long-term results of a multicenter study on subthalamic and pallidal stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010, 25: 578-586.

Volkmann J, Albanese A, Kulisevsky J, Tornqvist AL, Houeto JL, Pidoux B, Bonnet AM, Mendes A, Benabid AL, Fraix V, Van Blercom N, Xie J, Obeso J, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Guridi J, Schnitzler A, Timmermann L, Gironell AA, Molet J, Pascual-Sedano B, Rehncrona S, Moro E, Lang AC, Lozano AM, Bentivoglio AR, Scerrati M, Contarino MF, Romito L, Janssens M, Agid Y: Long-term effects of pallidal or subthalamic deep brain stimulation on quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009, 24: 1154-1161.

Anderson VC, Burchiel KJ, Hogarth P, Favre J, Hammerstad JP: Pallidal vs subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2005, 62: 554-560.

Apetauerova D, Ryan RK, Ro SI, Arle J, Shils J, Papavassiliou E, Tarsy D: End of day dyskinesia in advanced Parkinson's disease can be eliminated by bilateral subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord. 2006, 21: 1277-1279.

Romito LM, Contarino MF, Vanacore N, Bentivoglio AR, Scerrati M, Albanese A: Replacement of dopaminergic medication with subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson's disease: long-term observation. Mov Disord. 2009, 24: 557-563.

Benabid AL, Torres N: New targets for DBS. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012, 18 (Suppl 1): S21-23.

Lee MS, Rinne JO, Marsden CD: The pedunculopontine nucleus: its role in the genesis of movement disorders. Yonsei Med J. 2000, 41: 167-184.

Moreau C, Defebvre L, Devos D, Marchetti F, Destee A, Stefani A, Peppe A: STN versus PPN-DBS for alleviating freezing of gait: toward a frequency modulation approach?. Mov Disord. 2009, 24: 2164-2166.

Stefani A, Lozano AM, Peppe A, Stanzione P, Galati S, Tropepi D, Pierantozzi M, Brusa L, Scarnati E, Mazzone P: Bilateral deep brain stimulation of the pedunculopontine and subthalamic nuclei in severe Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2007, 130: 1596-1607.

Yelnik J: PPN or PPD, what is the target for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease?. Brain. 2007, 130: e79-author reply e80

Peppe A, Gasbarra A, Stefani A, Chiavalon C, Pierantozzi M, Fermi E, Stanzione P, Caltagirone C, Mazzone P: Deep brain stimulation of CM/PF of thalamus could be the new elective target for tremor in advanced Parkinson's Disease?. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008, 14: 501-504.

Karlsson F, Unger E, Wahlgren S, Blomstedt P, Linder J, Nordh E, Zafar H, van Doorn J: Deep brain stimulation of caudal zona incerta and subthalamic nucleus in patients with Parkinson's disease: effects on diadochokinetic rate. Parkinsons Dis. 2011, 2011: 605607-doi: 10.4061/2011/605607

Lundgren S, Saeys T, Karlsson F, Olofsson K, Blomstedt P, Linder J, Nordh E, Zafar H, van Doorn J: Deep brain stimulation of caudal zona incerta and subthalamic nucleus in patients with Parkinson's disease: effects on voice intensity. Parkinsons Dis. 2011, 2011: 658956-doi: 10.4061/2011/658956

Sundstedt S, Olofsson K, van Doorn J, Linder J, Nordh E, Blomstedt P: Swallowing function in Parkinson's patients following Zona Incerta deep brain stimulation. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012, 126: 350356.

Taira T: Will ventralis intermedius deep brain stimulation for tremor be replaced by posterior subthalamic area or caudal zona incerta stimulation?. World Neurosurg. 2012, 78: 445-446.

Hauser RA, Schwarzschild MA: Adenosine A2A receptor antagonists for Parkinson's disease: rationale, therapeutic potential and clinical experience. Drugs Aging. 2005, 22: 471-482.

Hsieh PW, Hung CF, Fang JY: Current prodrug design for drug discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2009, 15: 2236-2250.

Sozio P, Cerasa LS, Abbadessa A, Di Stefano A: Designing prodrugs for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2012, 7: 385-406.

Politis M, Wu K, Loane C, Kiferle L, Molloy S, Brooks DJ, Piccini P: Staging of serotonergic dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: an in vivo 11C-DASB PET study. Neurobiol Dis. 2010, 40: 216-221.

Politis M, Wu K, Loane C, Quinn NP, Brooks DJ, Rehncrona S, Bjorklund A, Lindvall O, Piccini P: Serotonergic neurons mediate dyskinesia side effects in Parkinson's patients with neural transplants. Sci Transl Med. 2010, 2: 38ra46.

Dunnett SB, Bjorklund A, Lindvall O: Cell therapy in Parkinson's disease - stop or go?. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001, 2: 365-369.

Marks WJ, Bartus RT, Siffert J, Davis CS, Lozano A, Boulis N, Vitek J, Stacy M, Turner D, Verhagen L, Bakay R, Watts R, Guthrie B, Jankovic J, Simpson R, Tagliati M, Alterman R, Stern M, Baltuch G, Starr PA, Larson PS, Ostrem JL, Nutt J, Kieburtz K, Kordower JH, Olanow CW: Gene delivery of AAV2-neurturin for Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9: 1164-1172.

Marks WJ, Ostrem JL, Verhagen L, Starr PA, Larson PS, Bakay RA, Taylor R, Cahn-Weiner DA, Stoessl AJ, Olanow CW, Bartus RT: Safety and tolerability of intraputaminal delivery of CERE-120 (adeno-associated virus serotype 2-neurturin) to patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease: an open-label, phase I trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7: 400-408.

Gasmi M, Herzog CD, Brandon EP, Cunningham JJ, Ramirez GA, Ketchum ET, Bartus RT: Striatal delivery of neurturin by CERE-120, an AAV2 vector for the treatment of dopaminergic neuron degeneration in Parkinson's disease. Mol Ther. 2007, 15: 62-68.

Herzog CD, Dass B, Holden JE, Stansell J, Gasmi M, Tuszynski MH, Bartus RT, Kordower JH: Striatal delivery of CERE-120, an AAV2 vector encoding human neurturin, enhances activity of the dopaminergic nigrostriatal system in aged monkeys. Mov Disord. 2007, 22: 1124-1132.

Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, Fitzsimons HL, Mattis P, Lawlor PA, Bland RJ, Young D, Strybing K, Eidelberg D, During MJ: Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson's disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007, 369: 2097-2105.

LeWitt PA, Rezai AR, Leehey MA, Ojemann SG, Flaherty AW, Eskandar EN, Kostyk SK, Thomas K, Sarkar A, Siddiqui MS, Tatter SB, Schwalb JM, Poston KL, Henderson JM, Kurlan RM, Richard IH, Van Meter L, Sapan CV, During MJ, Kaplitt MG, Feigin A: AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10: 309-319.

Luo J, Kaplitt MG, Fitzsimons HL, Zuzga DS, Liu Y, Oshinsky ML, During MJ: Subthalamic GAD gene therapy in a Parkinson's disease rat model. Science. 2002, 298: 425-429.

Sgambato-Faure V, Cenci MA: Glutamatergic mechanisms in the dyskinesias induced by pharmacological dopamine replacement and deep brain stimulation for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2012, 96: 69-86.

Krack P, Batir A, Van Blercom N, Chabardes S, Fraix V, Ardouin C, Koudsie A, Limousin PD, Benazzouz A, LeBas JF, Benabid AL, Pollak P: Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349: 1925-1934.

Krack P, Fraix V, Mendes A, Benabid AL, Pollak P: Postoperative management of subthalamic nucleus stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002, 17 (Suppl 3): S188-197.

Limousin P, Pollak P, Hoffmann D, Benazzouz A, Perret JE, Benabid AL: Abnormal involuntary movements induced by subthalamic nucleus stimulation in parkinsonian patients. Mov Disord. 1996, 11: 231-235.

Hagell P, Piccini P, Bjorklund A, Brundin P, Rehncrona S, Widner H, Crabb L, Pavese N, Oertel WH, Quinn N, Brooks DJ, Lindvall O: Dyskinesias following neural transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2002, 5: 627-628.

Freed CR, Greene PE, Breeze RE, Tsai WY, DuMouchel W, Kao R, Dillon S, Winfield H, Culver S, Trojanowski JQ, Eidelberg D, Fahn S: Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 710-719.

Politis M: Dyskinesias after neural transplantation in Parkinson's disease: what do we know and what is next?. BMC Med. 2010, 8: 80.

Ahlskog JE, Muenter MD: Frequency of levodopa-related dyskinesias and motor fluctuations as estimated from the cumulative literature. Mov Disord. 2001, 16: 448-458.

Fahn S: The spectrum of levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Ann Neurol. 2000, 47 (Suppl 1): S2-9. discussion S9-11

Klawans HL, Goetz C, Bergen D: Levodopa-induced myoclonus. Arch Neurol. 1975, 32: 330-334.

Nutt JG: Motor fluctuations and dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2001, 8: 101-108.

Gour J, Edwards R, Lemieux S, Ghassemi M, Jog M, Duval C: Movement patterns of peak-dose levodopa-induced dyskinesias in patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain Res Bull. 2007, 74: 66-74.

Fenney A, Jog MS, Duval C: Short-term variability in amplitude and motor topography of whole-body involuntary movements in Parkinson's disease dyskinesias and in Huntington's chorea. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008, 110: 160-167.