Abstract

Background

Febrile neutropenia is a frequently occurring and occasionally life-threatening complication of treatment for childhood cancer. Many biomarkers have been proposed as predictors of adverse events. We aimed to undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize evidence on the discriminatory ability of initial serum biomarkers of febrile neutropenic episodes in children and young people.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Center for Reviews and Dissemination Methods, using three random effects models to undertake meta-analysis. It was registered with the HTA Registry of systematic reviews, CRD32009100485.

Results

We found that 25 studies exploring 14 different biomarkers were assessed in 3,585 episodes of febrile neutropenia. C-reactive protein (CRP), pro-calcitonin (PCT), and interleukin-6 (IL6) were subject to quantitative meta-analysis, and revealed huge inconsistencies and heterogeneity in the studies included in this review. Only CRP has been evaluated in assessing its value over the predictive value of simple clinical decision rules.

Conclusions

The limited data available describing the predictive value of biomarkers in the setting of pediatric febrile neutropenia mean firm conclusions cannot yet be reached, although the use of IL6, IL8 and procalcitonin warrant further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With multi-modality therapies, children with malignancy have an excellent chance of survival, with overall rates approaching 75% [1]. Deaths are largely due to their disease, but around 16% of deaths are from complications of therapy [2, 3]. This proportion depends on the underlying malignancy, and the risk of death from infection remains high in some groups, for example, acute myeloid leukemia [4]. Robust risk stratification, which reliably predicted those children at high risk of complications, could target more aggressive management, where children at very low risk of having a significant infection could be treated with reduced intensity and/or duration of hospitalized antibiotic therapy [5]. There are a wide range of differing approaches to this risk stratification, largely built on simple clinical data [6–8], demonstrating only moderate discriminatory ability.

The ability of specific serum biomarkers to predict adverse consequences in patients with febrile neutropenia has been explored, for example, C-reactive protein (CRP), pro-calcitonin (PCT), interleukin-6 (IL6) or interleukin-8 (IL8) [9–12]. These studies have been small in the numbers of patients and episodes and the researchers could not reach definitive conclusions. Drawing these reports together and synthesizing their results should improve our understanding of their clinical usefulness.

Although systematic reviews have been conducted previously in adults [13] and non- immunocompromised children [14, 15], their results are difficult to compare. There are data to suggest children and adults with neutropenic fever vary in the nature of the infections which afflict them [16], implying any review needs to take into account the specific population under study.

This review aimed to identify, critically appraise and synthesize information on the use of biomarkers at initial evaluation for the prediction of the outcome of febrile neutropenic episodes in children/young adults and to highlight important problems in the current methods used in such analyses.

Methods

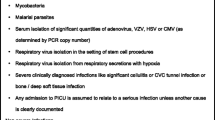

The review was conducted in accordance with "Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care" [17] and registered on the HTA Registry of Systematic Reviews: CRD32009100485. It sought studies which evaluated the diagnostic ability of serum biomarkers of inflammation/infection in children or young people aged 0 to 18 years of age, taken at the onset (within 12 hours) of an episode of febrile neutropenia. Both prospective and retrospective cohorts were included, but those using a case-control approach were excluded as these have been previously shown to exaggerate diagnostic accuracy estimates [18].

Search strategy and selection criteria

An electronic search strategy (See Additional file 1) was developed to examine a range of databases from inception to February 2009, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Conference Proceedings Citation Index - Science and LILACS.

Reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included articles were reviewed for further relevant articles. Published and unpublished studies were sought without language restrictions. Non-English language studies were translated. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies for inclusion, and then the full text of retrieved articles. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The validity of each study was assessed using 11 of the 14 questions from the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) assessment tool for diagnostic accuracy studies [19] (see footnote of Additional file 2). The QUADAS tool was adapted specifically for the review, as suggested by current guidance [20], omitting questions on "time between index and reference test", "intermediate results" and "explanation of withdrawals". The index test (biomarkers) and reference test were always examined within a single episode of febrile neutropenia, making this question indiscriminating. Tests of biomarkers are not reported as 'positive' and 'negative', and so "intermediate" results are not found in these types of studies. Rather than addressing "incomplete data" as a validity item, it was addressed in the data analysis.

Data were extracted by one researcher using a standardized data extraction form and accuracy confirmed independently by a second; except with foreign language papers where a translator working with a reviewer undertook the extraction. Clinical data extracted included participant demographics, geographical location, participant inclusion/exclusion criteria and antibiotics used. Methodological information included methods used to adjust the predictive estimate, including the variables considered, and methods of analysis. The reference standard outcomes considered relevant included survival, need for intensive/high-dependency care, single organ impairment, invasive bacterial or fungal infection, presence of documented infection, including radiologically confirmed pneumonia, and duration of hospitalization. The sensitivity and specificity of the biomarkers were extracted, preferentially as 2 × 2 tables comparing dichotomized test results against the reference standard. Where data were only presented as mean and standard deviation, conversion was undertaken using the assumption of Normality and deriving a 2 × 2 table for cut-offs reported by other studies (Anzures, Cochrane Colloquium Freiburg 2008).

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Quantitative synthesis was undertaken for studies which tested the same diagnostic test for similar clinical outcomes and, where appropriate, was investigated for sources of heterogeneity.

Three approaches were used for meta-analysis. The first approach (Method 1) pooled data from the most commonly reported threshold, using a single data point from each study that provided relevant information, for example, each study reporting serum CRP > 50 mg/dL. This was expressed as the average test sensitivity and specificity, with a 95% confidence interval. This was calculated by fitting the standard bivariate random effects model using STATA (version 10) [21] with metandi [22] and midas [23] for analyses of four or more studies; for those with fewer than four studies a random effects linear regression was directly fitted using xmelogit. The bivariate model is the most commonly used technique in diagnostic meta-analysis, and has benefits of being easily interpretable, as it provides a point estimate of the test accuracy in this context for a defined cut-off value, and is technically straightforward to undertake. Its weaknesses lie in the partial use of data from all the included studies, (since accuracy at multiple test cut-offs was available from many studies), which may lead to reduced power and consequent imprecision, and increased risk of bias from a selective use of data.

The second approach (Method 2) again pooled one data point from each study, but combined information from multiple thresholds, for example, serum CRP > 40 mg/dL, > 50 mg/dL and > 90 mg/dL, and the output was expressed as a hierarchical summary receiver operator curve (HSROC). The HSROC describes the relationship between sensitivity and specificity derived from the individual receiver operator curves (ROC) of each study. In this way, it describes the 'average' relationship between a continuous cut-off value and discriminatory ability in the 'average' population. This increases the information used in the meta-analysis and better represents the data. The same routines were used in STATA (version 10) [21] to produce these estimates. This approach is again technically straightforward to perform, and the output allows clinicians to estimate how changing thresholds will alter the diagnostic utility of the test under study. Its weaknesses relate to the difficulty in interpreting exactly what performance is associated with each cut-off level, and its lack of explicit inclusion of threshold data when producing the curve.

The third analysis (Method 3) allowed multiple data points from multiple thresholds from each study to be included, and was undertaken using a multinomial random effects method deriving proportions of the population with/without the outcome at each cut-off level of the biomarkers. These were then used to derive likelihood ratios for each level [24]. This provides the richest model, including all of the available data from the studies and should produce the clearest possible descriptions of the predictive value of the biomarkers. This was accomplished using a previously published method [8] and non-informative priors. Analyses were undertaken using WinBUGS 1.4.3 [25]. The code is available upon request. This method is theoretically superior to the other methods, as it includes all of the available data, unlike Method 1, explicitly uses the threshold values, unlike Method 2, and produces threshold-specific estimates of diagnostic test performance, which can be interpreted directly by clinicians. It is the most technically challenging of all the methods used, requiring specific code to be written for each analysis, rather than the use of easily available software packages.

Heterogeneity between study results was explored through consideration of study populations, design, predictor variables and outcomes. Meta-regression was not undertaken due to the small number of studies. When quantitative synthesis was not possible, a narrative approach was used to synthesize the information.

Results

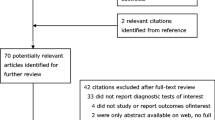

Three hundred, sixty-eight articles were initially reviewed, and 72 retrieved for more detailed examination. Twenty-five articles provided quantitative outcome data in the form required for the review (see Additional file 3). The included studies included 2,089 patients and over 3,585 episodes, assessing 14 different markers of inflammation or infection (see Table 1). The study outcomes were grouped into: bacteremia, invasive fungal infection, significant/documented bacterial infection, sepsis and death. The population in the studies varied, with most being a mixture of hematological and solid malignancies, and very little data from stem cell transplant recipients (see Table 2 for further detail). Thirteen of these contributed to 1 or more meta-analyses while the remaining 12 studies did not provide data which could be included in any meta-analysis. (see Figure 1). Three biomarkers and 2 outcomes could be included in the meta-analysis: 11 studies provided data on CRP [9, 26–35] and documented infection. Four studies provided data on PCT [28, 29, 31, 33] and documented infection. Four provided data on IL6 [31, 36–38] and documented infection or gram negative bacteremia.

Quality assessment

The studies varied in quality; see Additional file 2. The major deficiencies in most studies were in a failure to report if the marker test and outcomes were interpreted blind to each other. One study [26] assessing CRP demonstrated a potential contamination of the reference standard with the diagnostic test: the outcome included CRP > 150 mg/dl. One short report did not detail the exact outcome used [39]. Twenty different definitions of 'febrile neutropenia' were described, including six definitions of neutropenia ranging from < 200 cells/mm3 to < 1,000 cells/mm3; four definitions of peak fever, from > 37.5°C to > 39°C; and six of sustained temperature, from > 38°C to > 38.5°C over varying durations. There were a total of 14 combinations to define 'febrile'.

Data handling and analysis

Detailed analysis of the statistical modeling used in the original studies revealed potential problems in adjustment of estimates for other factors, limited event-per-variable ratios, poorly described handling of multiple episodes and missing data, and use of data-driven dichotomies in the reporting of test accuracy.

Diagnostic test performance

Data were available for meta-analysis for CRP for microbiologically or clinically documented infection; for PCT assessing microbiologically or clinically documented infection; and IL6 reporting microbiologically or clinically documented infection, and gram negative bacteremia. Individual results for these studies and outcomes are given in Additional file 3.

Meta-analysis using the three specified approaches illustrated how the standard, simple approach to pooling of test accuracy data may be misleading and lead to clinically inappropriate conclusions.

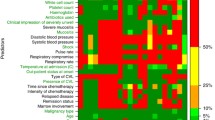

For studies with similar outcomes and where identical cut-off values were reported in more than one study, meta-analysis was undertaken to calculate a single diagnostic test accuracy estimate using the standard random effects bivariate approach: Method 1 (see Table 3 and Figure 2). This approach is the commonly applied technique, yet does not take into account the inconsistency of the full data set (see Methods).

There is marked heterogeneity in the results of this meta-analysis, with sensitivity heterogeneous in all markers, and specificity most heterogeneous in PCT and CRP. This can be appreciated by comparison of the point estimates and confidence intervals in the y (sensitivity) axis and x (reverse-specificity) axis in Figure 2.

Using the second approach, producing HSROC, it was possible for CRP and PCT to detect 'documented infection': Method 2. No further HSROC curves were derived as no other combinations of outcome and biomarker were available in more than three studies. In this analysis, the threshold variation was not adhered to, as can be seen in the example of CRP. Figure 3a shows the curve without threshold, and 3b shows how the values are not in the order expected. The expectation is that a higher cut-off produces a lower sensitivity and higher specificity; this is not the case and so this makes clinical interpretation of the curve impossible.

The meta-analysis method (Method 3), which maximizes the use data, including multiple thresholds from studies using a multinomial random effects model, demonstrates that these problems arise because of the inconsistencies in the reported data. Again, the CRP data are used to demonstrate this (see Figure 4). This shows that some of the lower thresholds are less sensitive than higher thresholds; for example, using a cut-off of > 20 mg/dL produced more false negative results than a cut-off of > 50 mg/dL. These differences are beyond those expected by chance and led to the analyses producing clinically meaningless results. This is likely to be due to the extreme heterogeneity and sparse data.

Data on the diagnostic value of nine other markers are presented in Table 4. IL8 was most frequently described [27, 38, 39]. Most of these studies were exploratory, proposing new biomarkers and deriving cut-offs, for example, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 or Adenosine deaminase. The predictive value of these biomarkers is also heterogeneous, and subject to potential biases.

Discussion

This systematic review of the predictive value of serum markers of inflammation and infection in children presenting with febrile neutropenia found 25 studies reporting 14 different markers. Of these, CRP, PCT, IL6 and IL8 were most commonly examined. The finding of a diverse range of potentially useful markers, but such little consistency across studies, is unfortunately common in such research [40], and may reflect the relative lack of coordination in supportive care studies.

The studies presented similar challenges in reporting, methodology and analysis. Reporting if the test was interpreted 'blind' to the results of the outcome analysis, and vice-versa, was very poorly reported. Many studies failed to assess if the marker had supplementary value above the simple admission data collected by clinicians at every encounter: age, malignancy, temperature, vital statistics and blood count. Analysis of the data was frequently undertaken by episode, with no account of multiple admissions for the same patient. Such an analysis ignores the variation which may be expected from genetic polymorphisms for the production of the biomarker under investigation [39], or in individual genetic susceptibility to infection [41, 42]. The biomarker cut-off values reported were frequently derived from the dataset to which they were then applied, which is likely to produce significant overestimations of accuracy [43]. The data were sometimes presented as mean and standard deviation estimates, from which measures of test accuracy were derived. Although this may raise concerns because of the assumption of a normal distribution, there is some empiric justification for this procedure [44].

Quantitative meta-analysis using three approaches demonstrated how the commonly used, simple techniques may fail to reflect inconsistencies in the whole data set and so produce misleadingly precise results. The example of this review is important to recall when appraising other reviews where inconsistencies may not have been as extensively investigated.

The analysis undertaken using only the most commonly reported cut-off in a restricted number of studies produced excessively precise results which did not reflect the uncertainty of the whole data set, and so should be rejected. A similar problem was found with the use of data points with different thresholds to produce a hierarchical summary receiver operator curve (HSROC). The HSROC modelled by these techniques does not take into account the actual value of the thresholds. This is frequently reasonable: it is impossible to quantify the thresholds used by different radiologists to call a radiograph 'positive' for pneumonia. In cases where the values are known, an ordered relationship should be possible to determine, flowing from high to low cut-offs from left to right on the curve. This ordered relationship did not hold true for analyses of CRP and PCT and so should call into question analyses in other studies which do not assess whether thresholds vary according to the implicit structure of the model.

A previously developed [8] technique to undertake the ordered pooling of all the results was used to attempt to overcome these difficulties of only selective use of the data, and of incorrect relationships between test thresholds. This approach failed to produce meaningful results for the ability of PCT and CRP to identify patients who developed a documented infection, reflecting the inconsistencies and great heterogeneity of the data.

Some of the observed heterogeneity may be due to differences in measurement between apparently similar outcomes. While bacteremia is likely to be similarly reported across the studies, the diagnosis of a soft-tissue infection may vary between clinicians and centers. Very few studies reported in detail the exact definitions of the outcomes they reported. Further variation may have been introduced by the varying definitions of fever and neutropenia. In this review, 20 different combinations of criteria were used to define febrile neutropenia. These data could not be directly assessed to explore their relationship with the diagnostic value of the biomarkers, but as the depth of neutropenia and peak, and duration of temperature may affect the generation of biomarkers, the variation may further account for some of the heterogeneity. Additionally, although the assay techniques used in the studies were reported to be similar, there was no calibration of assays across the various studies. Other differences in the populations studied, such as the nature of the malignancies, recent surgical interventions and duration of therapy, may also add heterogeneity to interpreting markers which are themselves affected by a malignant disease. A more prosaic reason for heterogeneity may be publication bias: the tendency for reports demonstrating good predictive value to be published than those showing poor discrimination [45–47].

In order to interpret the information from this review in a clinically meaningful way, both the estimates of predictive effectiveness and the uncertainty that surrounds these estimates need to be taken into account. CRP has been most extensively studied in this setting; it is a ubiquitous test and the only one which has been shown to add to the predictive ability of clinically-based decision rules [26, 34]. These studies chose two differing cut-offs (> 50 mg/dl [26] or > 90 mg/dl [34]). It is at best only moderately discriminatory in the setting of detecting documented infection (Sensitivity 0.65; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.84, Specificity 0.73; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.82), which is in keeping with estimates drawn from its value in the detection of serious bacterial infection in non-neutropenic children [48], and may be a significant overestimation of its value. The clinical role of CRP as a screening tool may be limited, however, if another biomarker is shown to be a more discriminatory test.

Data from this review and meta-analytic comparisons of CRP and PCT in the non-neutropenic population [49] are suggestive of the improved predictive value of PCT over CRP. This has a strong pathophysiological basis, as PCT levels are reported to rise within 3 to 4 hours in response to infection as compared with the 24 to 48 hours required for CRP [33]. However, the data for the improved predictive value of PCT are quite varied (see Additional file 3 and previously published reviews [13]). This may be related to the degree of neutropenia, as reports from the post-transplant setting have shown disappointingly poor discrimination [50], or this again may be due to small studies and publication bias [47, 51]. Based on the data from this review, procalcitonin cannot yet be recommended for use in routine clinical practice

Similar pathophysiological claims for improved predictive ability can be advanced for IL6 and IL8 [52]. In this review, IL6 level shows potential to be a better discriminator than CRP of those children who will develop a serious infectious complication. IL8 also appears to have moderate discriminatory ability and has been used in combination with clinical data in a small pilot study to withhold antibiotics to a highly select group of patients with febrile neutropenia [53]. Both of these cytokines show promise, and should be subject to further investigation.

Given the very limited data available for other potential biomarkers of infection in the setting of pediatric febrile neutropenia identified by this review, no strong clinical conclusions for their use can be reached without further studies.

These conclusions are drawn from an extensive and detailed systematic review of the available evidence using advanced techniques of meta-analysis, supplemented by rational clinical and pathophysiological reasoning. It should be clearly understood that they are uncertain and unstable, as only small amounts of new data may substantially alter these findings.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates flaws in our current understanding of the value of biomarkers in the prediction of adverse outcomes from episodes of febrile neutropenia, but also provides us with clear opportunities for development. All further investigation should estimate the additional value of biomarker measurements, beyond the discrimination already achieved by clinical variables. This should take into account key features of the treatment, for example, stem-cell transplantation and any clinically defined risk stratification already undertaken.

This includes the use of individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis, which should allow the effective added-value of markers to be measured when the best clinical data have been taken into account in differing sub-groups. Such a venture is in progress [54]. The biomarkers IL6, IL8 and PCT appear promising, and should certainly be subject to new primary studies investigating more thoroughly the prediction of significant infectious morbidity, which includes both clearly defined infections and the sepsis syndrome, across a variety of clinical settings. By developing harmonized definitions of outcomes for such studies, greater confidence could be placed upon their results. The new SIOP Supportive Care group is ideally placed to lead on such a venture, and allow pediatric oncology/hematology to once more push the boundaries of international, collaborative clinical research.

Abbreviations

- CRD:

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- FNP:

-

febrile neutropenia

- HSROC:

-

hierarchical summary receiver operator curve

- IL6:

-

interleukin 6

- IL8:

-

interleukin 8

- PCT:

-

procalcitonin

- QUADAS:

-

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

- ROC:

-

receiver operator curve

- SIOP:

-

Societe Internationale d'Oncologie Paediatrique.

References

Pritchard-Jones K, Kaatsch P, Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller CA, Coebergh JWW: Cancer in children and adolescents in Europe: developments over 20 years and future challenges. Eur J Cancer. 2006, 42: 2183-2190. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.06.006.

Freycon F, Trombert-Paviot B: Trends in treatment-related deaths (TRDs) in childhood cancer and leukemia over time: a follow-up of patients included in the childhood cancer registry of the Rhone-Alpes region in France (ARCERRA). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008, 50: 1213-1220. 10.1002/pbc.21506.

Hargrave DR, Hann IM: Progressive reduction in treatment-related deaths in Medical Research Council childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia trials from 1980 to 1997 (UKALL VIII, × and XI). Br J Haematol. 2001, 112: 293-299. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02543.x.

Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, Dworzak M, Stary J, Lehrnbecher T: Early deaths and treatment-related mortality in children undergoing therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: analysis of the multicenter clinical trials AML-BFM 93 and AML-BFM 98. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 4384-4393. 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.191.

Ammann RA, Simon A, de Bont ES: Low risk episodes of fever and neutropenia in pediatric oncology: Is outpatient oral antibiotic therapy the new gold standard of care?. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005, 45: 244-247. 10.1002/pbc.20287.

Phillips B, Selwood K, Lane SM, Skinner R, Gibson F, Chisholm JC: Variation in policies for the management of febrile neutropenia in United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group centres. Arch Dis Child. 2007, 92: 495-498. 10.1136/adc.2006.102699.

Boragina M, Patel H: Management of febrile neutropenia in pediatric oncology patients: a Canadian survey. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007, 48: 521-526. 10.1002/pbc.20810.

Phillips B, Wade R, Stewart LA, Sutton AJ: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the discriminatory performance of risk prediction rules in febrile neutropaenic episodes in children and young people. Eur J Cancer. 2010, 46: 2950-2964. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.024.

Santolaya M, Cofre J, Beresi V: C-reactive protein: a valuable aid for the management of febrile children with cancer and neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1994, 18: 589-595. 10.1093/clinids/18.4.589.

Nijhuis CO, Kamps WA, Daenen SMG, Gietema JA, van der Graaf WTA, Groen HJM, Vellenga E, ten Vergert EM, Vermeulen KM, de Vries-Hospers HG, de Bont ESJM: Feasibility of withholding antibiotics in selected febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 7437-7444. 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5264.

Lehrnbecher T, Fleischhack G, Hanisch M, Deinlein F, Simon A, Bernig T, Chanock SJ, Klingebiel T: Circulating levels and promoter polymorphisms of interleukins-6 and 8 in pediatric cancer patients with fever and neutropenia. Hematologica. 2004, 89: 234-236.

Stryjewski GR, Nylen ES, Bell MJ, Snider RH, Becker KL, Wu A, Lawlor C, Dalton H: Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and a rapid and sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors for the determination of bacterial sepsis in febrile neutropenic children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005, 6: 129-135. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149317.15274.48.

Sakr Y, Sponholz C, Tuche F, Brunkhorst F, Reinhart K: The role of procalcitonin in febrile neutropenic patients: review of the literature. Infection. 2008, 36: 396-407. 10.1007/s15010-008-7374-y.

Hugle T, Schuetz P, Mueller B, Laifer G, Tyndall A, Regenass S, Daikeler T: Serum procalcitonin for discrimination between septic and non-septic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 26: 453-456.

Dubos F, Martinot A, Gendrel D, Breart G, Chalumeau M: Clinical decision rules for evaluating meningitis in children. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009, 22: 288-293. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832b240e.

Hann I, Viscoli C, Paesmans M, Gaya H, Glauser M: A comparison of outcome from febrile neutropenic episodes in children compared with adults: results from four EORTC studies. International Antimicrobial Therapy Cooperative Group (IATCG) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Br J Haematol. 1997, 99: 580-588. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.4453255.x.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Systematic Review: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 2009, York, UK: University of York

Lijmer JG, Mol BW, Heisterkamp S, Bonsel GJ, Prins MH, van der Meulen JH, Bossuyt PM: Empirical evidence of design-related bias in studies of diagnostic tests. JAMA. 1999, 282: 1061-1066. 10.1001/jama.282.11.1061.

Whiting P, Rutjes A, Reitsma J, Bossuyt P, Kleijnen J: The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003, 3: 25-10.1186/1471-2288-3-25.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Systematic reviews of clinical tests. Systematic Review: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 2009, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. York, UK: University of York, 109-156.

Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. 2007, College Station, TX:StataCorp LP

Harbord R: METANDI: Stata module to perform meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. METANDI: Stata Module to Perform Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy. 2008, Bristol, UK: Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol

Dwamena BA: MIDAS: Stata module for meta-analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies. MIDAS: Stata Module for Meta-analytical Integration of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies. 2009, Chestnut Hill, MA: Boston College Department of Economics

Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL: Users' guides to the medical literature: III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994, 271: 703-707. 10.1001/jama.1994.03510330081039.

Lunn D, Thomas A, Best N, Spiegelhalter D: WinBUGS - a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput. 2000, 10: 325-337. 10.1023/A:1008929526011.

Ammann RA, Hirt A, Luthy AR, Aebi C: Identification of children presenting with fever in chemotherapy-induced neutropenia at low risk for severe bacterial infection. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003, 41: 436-443. 10.1002/mpo.10320.

El-Maghraby SM, Moneer MM, Ismail MM, Shalaby LM, El-Mahallawy HA: The diagnostic value of C-reactive protein, interleukin-8, and monocyte chemotactic protein in risk stratification of febrile neutropenic children with hematologic malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007, 29: 131-136. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180308770.

Hatzistilianou M, Rekleity A, Athanassiadou F, DeLutiis MA, Conti P, Catriu D: Serial procalcitonin responses in infection of children with secondary immunodeficiency. Clin Invest Med. 2007, 30: E75-85.

Hitoglou-Hatzi S, Hatzistilianou M, Gougoustamou D, Rekliti A, Agguridaki C, Athanassiadou F, Frydas S, Kotsis A, Catriu D: Serum adenosine deaminase and procalcitonin concentrations in neutropenic febrile children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Clin Exp Med. 2005, 5: 60-65. 10.1007/s10238-005-0067-2.

Katz JA, Mustafa MM, Bash RO, Cash JV, Buchanan GR: Value of C-reactive protein determination in the initial diagnostic evaluation of the febrile, neutropenic child with cancer. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992, 11: 708-712. 10.1097/00006454-199209000-00007.

Kitanovski L, Jazbec J, Hojker S, Gubina M, Derganc M: Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin and interleukin-6 values for predicting bacteremia and clinical sepsis in febrile neutropenic children with cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006, 25: 413-415. 10.1007/s10096-006-0143-x.

Riikonen P, Jalanko H, Hovi L, Saarinen UM: Fever and neutropenia in children with cancer: diagnostic parameters at presentation. Acta Paediatr. 1993, 82: 271-275. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12658.x.

Secmeer G, Devrim I, Kara A, Ceyhan M, Cengiz B, Kutluk T, Buyukpamukcu M, Yetgin S, Tuncer M, Uludag AK, Tezer H, Yildirim I: Role of procalcitonin and CRP in differentiating a stable from a deteriorating clinical course in pediatric febrile neutropenia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007, 29: 107-111. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180320b5b.

Santolaya ME, Alvarez AM, Becker A, Cofre J, Enriquez N, O'Ryan M, Paya E, Pilorget J, Salgado C, Tordecilla J, Varas M, Villarroel M, Viviani T, Zubieta M: Prospective, multicenter evaluation of risk factors associated with invasive bacterial infection in children with cancer, neutropenia, and fever. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 19: 3415-3421.

Spasova MI, Terzieva DD, Tzvetkova TZ, Stoyanova AA, Mumdzhiev IN, Yanev IB, Genev ED: Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, interleukin-10, and C-reactive protein in febrile neutropenia in children with malignant diseases. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2005, 47: 46-52.

Riikonen P, Saarinen UM, Teppo AM, Metsarinne K, Fyhrquist F, Jalanko H: Cytokine and acute-phase reactant levels in serum of children with cancer admitted for fever and neutropenia. J Infect Dis. 1992, 166: 432-436. 10.1093/infdis/166.2.432.

Lehrnbecher T, Venzon D, de Haas M, Chanock SJ, Kuhl J: Assessment of measuring circulating levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, C-reactive protein, soluble Fc gamma receptor type III, and mannose-binding protein in febrile children with cancer and neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999, 29: 414-419. 10.1086/520224.

Diepold M, Noellke P, Duffner U, Kontny U, Berner R: Performance of interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 serum levels in pediatric oncology patients with neutropenia and fever for the assessment of low-risk. BMC Infect Dis. 2008, 8: 28-10.1186/1471-2334-8-28.

Lehrnbecher T, Fleischhack G, Hanisch M, Deinlein F, Simon A, Bernig T, Chanock SJ, Klingebiel T: Circulating levels and promoter polymorphisms of interleukins-6 and 8 in pediatric cancer patients with fever and neutropenia. Haematologica. 2004, 89: 234-236.

Riley RD, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG: Prognostic markers in cancer: the evolution of evidence from single studies to meta-analysis, and beyond. Br J Cancer. 2009, 100: 1219-1229. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604999.

Frakking FN, van de Wetering MD, Brouwer N, Dolman KM, Geissler J, Lemkes B, Caron HN, Kuijpers TW: The role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in paediatric oncology patients with febrile neutropenia. Eur J Cancer. 2006, 42: 909-916. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.10.027.

Schlapbach LJ, Aebi C, Hansen AG, Hirt A, Jensenius JC, Ammann RA: H-ficolin serum concentration and susceptibility to fever and neutropenia in paediatric cancer patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009, 157: 83-89. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03957.x.

Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD: Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001, 54: 774-781. 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9.

Hozo S, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I: Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005, 5: 13-10.1186/1471-2288-5-13.

Kyzas PA, Denaxa-Kyza D, Ioannidis JPA: Quality of reporting of cancer prognostic marker studies: association with reported prognostic effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007, 99: 236-243. 10.1093/jnci/djk032.

Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J: Sources of variation and bias in studies of diagnostic accuracy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2004, 140: 189-202.

Knudsen TB, Kristiansen TB: Issues pertaining to data extraction and classification and publication bias in meta analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of markers for bacterial infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 40: 1372-1373. 10.1086/429507.

Sanders S, Barnett A, Correa-Velez I, Coulthard M, Doust J: Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of c-reactive protein to detect bacterial infection in nonhospitalized infants and children with fever. J Pediatr. 2008, 153: 570-574. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.023.

Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, Saint-Louis P, Lacroix J: Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 39: 206-217. 10.1086/421997.

Persson L, Engervall P, Magnuson A, Vikerfors T, Soderquist B, Hansson LO, Tidefelt U: Use of inflammatory markers for early detection of bacteraemia in patients with febrile neutropenia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004, 36: 365-371. 10.1080/00365540410020217.

Simon R, Altman DG: Statistical aspects of prognostic factor studies in oncology. Br J Cancer. 1994, 69: 979-985. 10.1038/bjc.1994.192.

de Bont ES, Vellenga E, Swaanenburg JC, Fidler V, Visser-van Brummen PJ, Kamps WA: Plasma IL-8 and IL-6 levels can be used to define a group with low risk of septicaemia among cancer patients with fever and neutropenia. Br J Haematol. 1999, 107: 375-380. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01707.x.

Oude Nijhuis C, Kamps WA, Daenen SMG, Gietema JA, van der Graaf WTA, Groen HJM, Vellenga E, Ten Vergert EM, Vermeulen KM, de Vries-Hospers HG, de Bont ESJM: Feasibility of withholding antibiotics in selected febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 7437-7444. 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5264.

Predicting Infectious Complications in Febrile Neutropenic Children with Cancer (PICNICC). [http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/projects/picnicc_clinician.htm]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/10/6/prepub

Acknowledgements

RSP is supported by an MRC Research Training Fellowship G0800472, which also supported RW for this review. TL, AJS and LAS received no external funding for their work in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RSP developed the concept for the review with LS and AJS. The protocol was further developed by RSP, RW, LS and AJS. Study screening and data extraction were undertaken by RSP and RW. Data analysis was undertaken by RSP and AJS. Interpretation and conclusions were drawn from this work by all authors, with particular clinical input from TL and methodological discussion with AJS. All authors have contributed to and reviewed the final paper. RSP is the guarantor of this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12916_2011_511_MOESM2_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 2: QUADAS assessments. Full list of assessed QUADAS (diagnostic test accuracy critical appraisal) criteria for the 25 included studies. (DOCX 15 KB)

12916_2011_511_MOESM3_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 3: Per-study results used in meta-analysis. Individual study results used in pooled analyses presented by marker, outcome and cut-off. (DOCX 18 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, R.S., Wade, R., Lehrnbecher, T. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the value of initial biomarkers in predicting adverse outcome in febrile neutropenic episodes in children and young people with cancer. BMC Med 10, 6 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-6