Abstract

The visual pathway is tasked with processing incoming signals from the retina and converting this information into adaptive behavior. Recent studies of the larval zebrafish tectum have begun to clarify how the 'micro-circuitry' of this highly organized midbrain structure filters visual input, which arrives in the superficial layers and directs motor output through efferent projections from its deep layers. The new emphasis has been on the specific function of neuronal cell types, which can now be reproducibly labeled, imaged and manipulated using genetic and optical techniques. Here, we discuss recent advances and emerging experimental approaches for studying tectal circuits as models for visual processing and sensorimotor transformation by the vertebrate brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

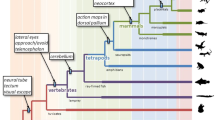

The basic 'macro-circuit' of the vertebrate visual system

The transformation of visual sensory inputs into motor and endocrine responses requires specialized neural processing, often distributed across multiple structures or pathways in the brain. A classical and still vigorous branch of neuroscience, best referred to as 'functional neuroanatomy', assigns functions to specific areas in the brain. The interconnectivity of multiple areas involved in a particular sensory or behavioral task are often represented using a set of boxes, connected by arrows. The most famous such wiring diagram identified roughly 40 visual processing areas in primates [1]. Similar 'macro-circuits' have been drawn up for the visual pathway of 'lower' vertebrates [2]. In toads, a detailed circuit underlying prey capture behavior has been derived from heroic work over three decades involving tract tracing and electrophysiological mapping [3] (Figure 1a). However, none of these studies has generated a comprehensive list of essential circuit components (cell types and their connections) for a specific behavior or the processing of a specific visual stimulus. This gap in our knowledge of 'micro-circuitry' is a major obstacle to understanding the mechanisms of perception and behavior.

Classical and neoclassical methods of parsing the visual system. (a) Neural network underlying prey capture in anuran amphibians [3]. Anatomical studies from 1969 to 1999 were compiled to show the complex interconnectivity of visual and olfactory inputs, forebrain and midbrain contributions, and motor outputs. The retina is boxed in blue, and retinorecipient regions are boxed in red. Such schemes provide a framework for further study but do not address the pathways' micro-circuitry. A, anterior thalamus; PT, pretectum; OT, optic tectum; R, retina; V, ventral thalamus. Modified from [3]. (b) Scheme showing the major retinofugal connections in the larval zebrafish. Colored circles are stand-ins for diverse cell types, already known or yet to be discovered. The quantities in parentheses are estimates of the number of cell types (data compiled from work on zebrafish and other cyprinids). The retina comprises three cellular layers with five types of photoreceptors (4 cones, 1 rod), at least 11 bipolar cell types, about 70 amacrine cell types [100], and so on. The number of tectal neuron types is also large. Distinct RGC types (colors) likely have specific roles and connections with ten retinorecipient arborization fields (AF1 to AF9 plus AF10, which is the tectum) in the brain. Some anatomical details (as far as known): the RGCs that are connected to AF7 project a collateral to SO; RGC axons projecting to SAC/SPV in the tectum are routed through AF9. Abbreviations: AC, amacrine cell; AF, arborization field; BC, bipolar cell; GC, ganglion cell; HC, horizontal cell; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; PhR, photoreceptor; PVN, periventricular neuron; SAC, stratum album centrale; SFGS, stratum fibrosum et griseum superficiale; SGC, stratum griseum centrale; SIN, superficial interneuron; SO, stratum opticum; SPV, stratum periventriculare.

The zebrafish has emerged as a valuable model system with which we can hope to close this gap [4–7]. Ten different anatomical areas have been identified that serve as targets for the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons that connect the eye to the brain [8] (Figure 1b). These ten arborization fields, referred to as AF1 to AF10, probably correspond to the primary visual nuclei identified in adult teleost fish and are homologous to areas in mammals, such as the suprachiasmatic nuclei (AF1), the pretectal nucleus of the optic tract (AF9) and the superior colliculus/optic tectum (AF10). Not very much is known about the behavioral functions of these arborization fields in zebrafish or other fish species (with the exception of the optic tectum - see below), but it is clear that specific visual functions are initiated by activation of a fixed complement of one or very few of these nuclei [9]. Table 1 contains a comprehensive list of visually evoked behaviors reported for zebrafish.

Here, we focus on the larval zebrafish tectum (AF10), a structure suitable for circuit analyses. The tectum sits at the surface of the brain (its name means 'roof' in Latin) and is therefore accessible to electrophysiology, laser ablations, optical imaging, and control of neuronal activity with optogenetic effectors. The tectum's broad function is known; it is involved in tasks that require a map of visual space, such as phototaxis, the approach of prey or the avoidance of obstacles (Table 1, third column). The tectum converts a visuotopic sensory map into a map of directed motor outputs. An intact tectum is dispensable for measurements of ambient light levels or for reflexes to broad moving stimuli, such as optomotor or optokinetic responses, visual background adaptation, the dorsal light reflex or photo-entrainment of circadian rhythms. In the laboratory, these behaviors can serve as negative controls for the specificity of tectum manipulations. The tectum's cellular architecture is beginning to be understood, providing an opportunity to match the structure of its micro-circuitry to its function. The zebrafish tectum is amenable to genetic manipulations. Some of the mutants and transgenic lines useful for analysis of tectal visuomotor function are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Important contributions to the renaissance of interest in the tectum's inner workings have also been made in Xenopus tadpoles. We will be lumping efforts in fish and frog together here, as they are truly complementary, each capitalizing on specific experimental advantages of the two systems.

Spatial patterning of information flow in the optic tectum

The zebrafish larval tectum is roughly divided into two regions, a deep cell body layer, the stratum periventriculare (SPV), and a superficial neuropil area, which contains the dendrites and axons of tectal neurons, a sparse assortment of tectal interneurons and afferent axons arriving at the tectum, chiefly from the retina (Figure 1b; colored circles indicate the diverse tectal cell types - see next section). Tectal processing begins with visual signals transmitted via the axons of RGCs. These axons enter the zebrafish tectal neuropil from the anterior end at six levels corresponding to the six retinorecipient laminae (Figure 1b) [10]. A similar pattern has been observed in adult teleosts [11]. As a strict rule, each RGC axon is targeted to a single lamina and arborizes exclusively in this lamina [12]. Most (80%) RGC axons innervate three sublayers of the stratum fibrosum et griseum superficiale (SFGS). A smaller number (15%) innervate the most superficial stratum opticum (SO). The remaining RGC axons (5%) project into the stratum griseum centrale (SGC) and into the interface between the stratum album centrale and the SPV (SAC/SPV). Each retinorecipient lamina is topographically organized: retinal axons project into the plane of each layer in a visuotopic order, such that the retinotectal map is in fact an array of six parallel maps stacked on top of each other. Objects in the forward visual field of the contralateral eye are represented in anterior tectum, whereas objects behind the fish are mapped to the posterior tectum. Objects in the upper visual field activate the dorsal (medial) tectum, whereas the ventral (lateral) tectum responds to visual stimuli from below the fish. This fine-grained map is thought to allow the localization of a stimulus in the visual field.

Several general rules govern information processing in the fish tectum. Information flows primarily from the superficial layers to the deeper layers. The vast majority of retinal afferents enter the superficial layers of the tectum, where they make excitatory (glutamatergic) synaptic connections with the dendrites of tectal interneurons. The information then travels along the vertically oriented dendrites of the periventricular neurons (PVNs) to the deeper layers [13]. As a demonstration of this, Kinoshita et al. [14] labeled tectal slices of adult rainbow trout with a voltage-sensitive dye and imaged the propagation of activity as current was applied to the anterior pole of the SO and SFGS. This cross-sectional view of the working tectum confirmed that the wave of depolarization proceeds in a stereotyped pattern. Fast depolarization travels anterior to posterior in the SO and SFGS, presumably along the paths of RGC axons. At each point along the anterior-posterior axis, a slower vertical depolarization is triggered, proceeding radially to the deeper SGC and SAC.

In the deeper neuropil layers, information is transmitted from the axons of interneurons to other interneurons or to tectal projection neurons that send axons to premotor areas in the midbrain and hindbrain. Intratectal connections are inhibitory (releasing the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and thus called GABAergic) or excitatory (releasing glutamate; glutamatergic). In addition, a small percentage of PVNs are cholinergic (releasing acetylcholine). Tectal outputs from the deeper neuropil layers are wired to the appropriate combination of premotor nuclei to govern behavioral responses. The cell bodies of most tectal neurons are spatially removed from the site of actual processing, which seems to take place exclusively in the neuropil. The cell body is not required as an intermediate between input and output because of the peculiar 'monopolar' morphology of fish tectal cells, which are reminiscent of insect neurons. The dendritic segments of the neurites are contiguous with the axonal segments. In the voltage-sensitive dye recordings mentioned above [14], the SPV was not detectably activated, suggesting that the bulk of activity 'fades' in the proximal neurites before it reaches the cell bodies.

This cellular architecture probably has functional implications. Bollmann et al. [15] imaged individually dye-loaded tectal neurons in Xenopus tadpoles. Their study demonstrated that visually evoked dendritic calcium elevations are unevenly elicited across individual dendritic trees in a pattern consistent with the retinotopic map. Given that many tectal neurons have axons that emerge from among the dendritic branches, different levels of activation across the dendritic arbor might influence neuronal output differently. If so, dendrites nearer the initial axon segment would have more influence than more distal branches in spike generation. It is not clear how this bias, favoring certain retinotopic positions over others, might contribute to the shape of the PVN's receptive field.

Studies of genetic mutants have helped to identify mechanisms that govern the processing of visual information in the zebrafish tectum (Table 2). One example is the blumenkohl mutant, which shows a selective deficit in the capture of small prey items (but not large ones). This impairment is due to a deletion of vesicular glutamate transporter 2, encoded by the vglut2a gene. In response to decreased levels of glutamate at retinotectal synapses, the arbors of retinal axons become enlarged, resulting in an increase of the receptive fields of tectal neurons [16]. Accurate processing of visual stimuli requires spatially precise vertical streams of activity that subsequently recruit small subpopulations of projection neurons to initiate a motor response. In blumenkohl mutants, these parallel processing streams are less precisely aligned owing to a greater overlap of receptive fields among neighboring tectal PVNs. This seems to degrade either visual acuity or motor control (or both).

Cell type diversity and complexity of tectal responses

Early electrophysiological recordings found heterogeneous responses among tectal neurons in adult zebrafish [17]. Some neurons were responsive to looming stimuli, others to moving edges or to objects of a certain size range. The colored circles in the schematic drawing in Figure 1b represent this diversity. Calcium imaging studies refined this work, showing that these distinct tuning properties arise early and are largely constant during embryonic and early larval development [18]. For these studies, larvae had their tecta loaded with a calcium indicator dye and were mounted with a miniature liquid-crystal display (LCD) screen for projecting images to the eye, and calcium signals from tectal cells were recorded by two-photon laser-scanning microscopy. PVNs could be sorted into numerous types according to their tuning profiles. Although some were broadly responsive, showing spontaneous and sustained activity in the dark, others were altogether unresponsive to the visual stimuli tested. However, the majority of PVNs were sensitive to spots in the visual field, with optimal responses to either stationary flashing spots, moving spots regardless of their size or direction, or small spots moving in particular directions. Thus, PVN ensemble activity probably encodes information about the location, size and movement of small objects in the visual field, evidently supporting the behavioral functions of the tectum.

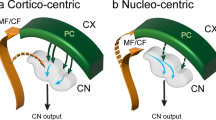

A landmark neuro-anatomical study, using the Golgi labeling technique, in adult goldfish, a species closely related to zebrafish (both are in the family Cyprinidae), catalogued tectal neuron types on the basis of cell body location and neurite arborization pattern [19] (Figure 2a). (Golgi-labeling is a classical neuroanatomical technique for sparsely labeling neurons; it shares a name - from the physician scientist Camillo Golgi - with the cellular compartment, but is functionally unrelated.) Anatomical surveys of transgenically labeled neurons have now extended this classical work to larval zebrafish. In a screen, our group [20, 21] identified three enhancer trap lines with strong and fairly specific expression of our Gal4 trap construct in tectal cells (Table 3). To examine individual neuron morphologies, we crossed these fish with carriers of a highly variegated UAS:mGFP construct contained within the Brn3c:Gal4, UAS:mGFP (BGUG) transgene (Table 3; GFP refers to green fluorescent protein and Brn3c to a member of the POU domain transcription factor family that is expressed in specific neurons). This method allows the visualization of single or sparse neurons with a membrane-targeted GFP. A distinct subset of these tectal neurons has been further characterized using a Dlx4/5:GFP transgenic reporter (ER, SJ Smith and HB, unpublished work). Together with single-cell electroporations labeling random subsets of tectal neurons with GFP [22], such 'genetic Golgi' stains have yielded a preliminary catalog of neuron types in larval zebrafish tectum (Figure 2b). Importantly, many of these neuron types resemble miniature versions of those described in the adult goldfish (compare Figure 2a and 2b) and other teleosts [23, 24].

Cell type diversity and (some) functional connectivity of the fish optic tectum. (a) Cells described from classical Golgi studies in the adult goldfish tectum [19]. Fourteen types of neuron were identified on the basis of cell body position and morphology. Modified from [19]. (b) A sampling of neuron morphologies observed in the larval zebrafish tectum using 'genetic Golgi' methods. These include: radial glia (RG), periventricular projection neurons (PVPNs), periventricular interneurons (PVINs) and superficial interneurons (SINs). Retinorecipient laminae in the tectum are indicated by shading. Note the diverse dendrite morphologies of both projection neurons and interneurons in the tectum. In particular, PVINs have been observed containing arbors that are non-stratified (nsPVINs), mono-stratified (msPVINs) or bi-stratified (bsPVINs). (c) Hypothetical neural circuit responsible for size tuning of PVNs in the optic tectum [36]. Retinal afferents targeting the superficial layers of the SO and SFGS form excitatory synapses onto PVINs containing superficial dendrites and an axonal arbor in a deeper layer. These PVINs may mediate the vertical flow of excitation in response to small visual stimuli by activating PVPNs with dendrites located in deeper neuropil layers. In contrast, large visual stimuli additionally activate SIN cells, which inhibit the PVIN-mediated vertical flow of information to PVPNs.

A quarter of the neurons in our survey [20, 21] have cell bodies in the SPV, radially oriented dendrites that reach to the superficial, retinorecipient layers and a local axon. We call this group the periventricular interneurons (PVINs). Little is known about their function. A substantial fraction of PVINs are GABAergic (the rest being glutamatergic or cholinergic), and these may filter incoming signals by inhibiting responses to non-salient stimuli. Feedforward inhibitory connections need to be in place for gain control given the high ratio of retinotectal axons to tectal efferents (neurons projecting from the tectum), estimated to be between 30:1 and 100:1 [25]. Most other periventricular neurons (70%) have axons exiting the tectum, reaching the hindbrain reticular formation, the medulla or the Raphe nucleus [20]. As a rule, these periventricular projection neurons (PVPNs) have dendrite arbors in the deep and intermediate regions of the neuropil, but not in the superficial SO/SFGS zone [20, 25, 26]. This morphology reinforces the observation that information flows chiefly from superficial to deep [13] and further suggests that processed, rather than raw, visual information governs tectal output.

A study [27] of efferent projections from the deep layers of the tectal neuropil to the hindbrain suggests that spatially patterned tectal outputs may help coordinate motor responses. The tectobulbar tract is composed of ipsilateral and contralateral projections to premotor structures in the hindbrain reticular formation. Hindbrain target neurons, in turn, project to primary motor neurons in the spinal cord. Sato et al. [27] used a clever combination of Gal4/UAS and Cre/LoxP systems to label small numbers of PVPNs, allowing a direct comparison of retinotopic position of tectal cell bodies with the hindbrain targets of their axons. Each mini-region of the tectum projects axons to a wide array of hindbrain segments (rhombomeres); for example, one area the size of a single retinotectal arbor had projections to almost all rhombomeres. These observations support a model in which tectal output from a small region reaches multiple premotor sites in order to coordinate a full body response.

The topographic organization of tectofugal projections to the reticular formation is functionally important, as shown in mammals, amphibians and fish [28–32]. In goldfish, anterior tectal efferents preferentially innervate midbrain sites that generate small horizontal eye movements, and posterior efferents innervate sites associated with large saccades (fast reset movements). In larval zebrafish, there is a similar mapping of tectal efferents onto the reticular formation [27]. Posterior tectal neurons are more likely to project to rhombomere 2, whereas middle to anterior neurons are more likely to innervate rhombomere 6. This suggests that the behavioral responses that are controlled by the reticular motor map are tailored to the location of the visual stimulus (as they should be). Although we do not know the identity or function of neurons in rhombomere 2 that receive input primarily from the posterior tectum, we predict that they have a role in executing a behavioral response, perhaps a large horizontal saccade or a turning response, to stimuli behind the animal.

Filtering of visual inputs by tectal micro-circuits

The role of local inhibition in the tectum for visual discrimination has been brought to light in two studies. In the first, Ramdya and Engert [33] surgically removed one tectum from a developing zebrafish embryo, which resulted in bilateral retinal innervation of the remaining tectum. This allowed them to characterize the binocular response properties of normally monocular tectal neurons. As in monocular tectum, binocular tectal neurons sometimes responded to motion in a direction-selective manner. Even a stripped-down motion stimulus, consisting of a dot jumping between two movie frames from left to right, generated a response. The authors exploited this unnatural binocular response to ask how motion sensitivity is generated in the tectum. They created an artificial 'motion stimulus' visible only to a binocular cell by parsing the dot's jump between the two eyes: one movie frame was shown only to the right eye and the other frame only to the left eye. Interestingly, this two-frame movie was sufficient to stimulate direction-sensitive tectal neurons. Given that neither retina's signal, on its own, could encode motion direction - each was shown a flashing, stationary dot - it can be concluded that circuitry intrinsic to the tectum underlies this sensitivity. These results are consistent with a model in which a direction-sensitive cell responsive to motion in the anterior direction is flanked anteriorly by retinorecipient cells that inhibit its activity. The direction-sensitive cell is therefore inhibited by its anterior neighbors and shows reduced activity when activated by a stimulus moving in a posterior direction across its receptive field, but responds more vigorously to an anteriorly moving spot. A similar model partially accounts for the directional selectivity seen in neurons of mammalian visual cortex [34, 35]. The Ramdya and Engert study [33] showed that such a direction-sensitive circuit exists in the zebrafish tectum and that it is probably hardwired (genetically specified).

The role of a specific, anatomically identified class of tectal inhibitory interneurons has recently emerged in another calcium imaging study carried out in our laboratory [36]. This work used the enhancer trap lines generated by Scott et al. [21] to express the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP in specific populations of tectal cells in order to image response dynamics in different tectal layers. As previously observed in the superior colliculus of mammals and corroborated in the larval zebrafish [18] (see above), many tectal neurons respond most strongly to small spots or bars in visual space. The new results identify a synaptic basis for this small-spot bias. When presented on a small LCD screen, all visual stimuli registered post-synaptic responses in the superficial neuropil (SO and SFGS), but only for spatially restricted stimuli were these signals fully propagated into the deeper neuropil (SGC and SAC). Tectal administration of bicuculline eliminated this size selectivity - in the presence of this GABA antagonist, large (50°) stimuli elicited responses in both superficial and deep neuropil. This implicates GABA-based inhibition in tectal filtering [36].

Further work was able to identify the cell type responsible for the selectivity [36]. With another Gal4 line, a type of interneuron called a superficial inhibitory neuron (SIN) could be labeled, whose cell body resides between SO and SFGS (Figure 2c). These cells have broad arbors in the SFGS, are GABAergic, and are probably homologous to Meek and Schellart's type III neurons (Figure 2a) [19]. Calcium imaging showed that these cells have the unusual property of responding to full-screen stimuli (and not to small stimuli). These data raised the possibility that SINs may be mediating the small spot selectivity of tectal filtering. To demonstrate their necessity in this process, SINs were photo-ablated with KillerRed [37]. This lesion had a similar effect to the application of bicuculline; deep tectal neuropil layers responded to large and small stimuli alike. Moreover, silencing of synaptic transmission by SINs with the tetanus toxin light chain impaired the fish's prey capture behavior, but not optomotor responses, a behavior independent of the tectum [38]. The new experiments [36] are the first elucidation of the role of a morphologically and genetically designated cell type in tectal processing.

Remaining questions and emerging approaches

The tectum integrates and processes visual information for export to premotor targets. Several steps in this sensorimotor transformation are still mysterious. The rules governing the PVIN to PVPN transmission are unknown, as are the contributions of afferent inputs to the tectum from diverse brain regions and sensory modalities [39–41]. And although efferent targets have been identified anatomically, we know little of the spatial or temporal patterns of tectal output activity. Even more mysteriously, tectal circuitry shows oscillations of activity in response to a periodic visual stimulus, which can continue long (tens of seconds) after the stimulus has stopped. These entrained mental 'reverberations' can even drive rhythmic motor activity [42]. We do not know which neuronal networks carry these oscillations, and whether they could potentially provide a substrate for working memory. A complete catalog of cell types, together with a comprehensive description of their connections within the tectum and beyond, will be useful to deduce this and other computations carried out by tectal micro-circuits.

Given the tectum's superficial position in the dorsal brain and the transparency of larval zebrafish, these questions can now be addressed using in vivo imaging and emerging optogenetic tools (reviewed in [43]). A large number of genetically encoded fluorescent and luminescent indicators of calcium concentration [42, 44–46], voltage [47–49] or neurotransmitter release [50–52] are available, some of which have already proven effective in zebrafish [53, 54]. Activating proteins, such as channelrhodopsins and LiGluR, and silencing proteins, including halorhodopsin, have recently been used in zebrafish to link targeted neurons conclusively to their roles in simple behaviors [55–60]. To take full advantage of these methods, more specific lines expressing transgenes in subsets of tectal neurons will have to be generated. Extrapolating from the rapid pace of recent discoveries, we expect that many of the anatomical components of the tectal circuitry will soon be understood in terms of their function in visual perception and behavior.

The mammalian superior colliculus also receives topographically organized retinal inputs and, like the tectum, has a stratified architecture that is principally visual in the superficial layers and multimodal with motor outputs in deeper layers [61]. Although extrinsic collicular circuits, including a number of command projections from the forebrain, are better characterized in mammals and birds than in zebrafish, understanding of the micro-circuitry is sketchy. In this way, investigations in different vertebrate species are complementary, and findings from one enable targeted studies in the other. Mammalian equivalents to SINs would be an appealing first target. The means by which PVINs and other tectal interneurons filter visual information could also be shared between fish and mammals, and as these processes are elucidated in the tectum, they will probably provide insights into collicular function.

More broadly, studies in the tectum have provided glimpses of how a three-dimensional array of neurons, whose architecture is simple by central nervous system standards, can filter input, represent visual space and detect motion. Genetic, behavioral and optical access to the tectum should allow the underlying cellular mechanisms to be described in the coming years. As these details emerge, we will probably learn important fundamentals of how diverse neural networks function.

References

Van Essen DC, Anderson CH, Felleman DJ: Information processing in the primate visual system: an integrated systems perspective. Science. 1992, 255: 419-423. 10.1126/science.1734518.

Fite KV: Pretectal and accessory-optic visual nuclei of fish, amphibia and reptiles: theme and variations. Brain Behav Evol. 1985, 26: 71-90. 10.1159/000118769.

Ewert JP, Buxbaum-Conradi H, Dreisvogt F, Glagow M, Merkel-Harff C, Röttgen A, Schörg-Pfeiffer E, Schwippert WW: Neural modulation of visuomotor functions underlying prey-catching behaviour in anurans: perception, attention, motor performance, learning. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2001, 128: 417-461. 10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00333-0.

Baier H: Zebrafish on the move: towards a behavior-genetic analysis of vertebrate vision. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000, 10: 451-455. 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00116-1.

Friedrich RW, Jacobson GA, Zhu P: Circuit neuroscience in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2010

Gahtan E, Baier H: Of lasers, mutants, and see-through brains: functional neuroanatomy in zebrafish. J Neurobiol. 2004, 59: 147-161. 10.1002/neu.20000.

Portugues R, Engert F: The neural basis of visual behaviors in the larval zebrafish. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009, 19: 644-647. 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.007.

Burrill JD, Easter SS: Development of the retinofugal projections in the embryonic and larval zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). J Comp Neurol. 1994, 346: 583-600. 10.1002/cne.903460410.

Ullén F, Deliagina TG, Orlovsky GN, Grillner S: Visual pathways for postural control and negative phototaxis in lamprey. J Neurophysiol. 1997, 78: 960-976.

Xiao T, Roeser T, Staub W, Baier H: A GFP-based genetic screen reveals mutations that disrupt the architecture of the zebrafish retinotectal projection. Development. 2005, 132: 2955-2967. 10.1242/dev.01861.

Vanegas H, Ito H: Morphological aspects of the teleostean visual system: a review. Brain Res. 1983, 287: 117-137.

Xiao T, Baier H: Lamina-specific axonal projections in the zebrafish tectum require the type IV collagen Dragnet. Nat Neurosci. 2007, 10: 1529-1537. 10.1038/nn2002.

Kinoshita M, Ito E: Roles of periventricular neurons in retinotectal transmission in the optic tectum. Prog Neurobiol. 2006, 79: 112-121. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.06.002.

Kinoshita M, Ueda R, Kojima S, Sato K, Watanabe M, Urano A, Ito E: Multiple-site optical recording for characterization of functional synaptic organization of the optic tectum of rainbow trout. Eur J Neurosci. 2002, 16: 868-876. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02160.x.

Bollmann JH, Engert F: Subcellular topography of visually driven dendritic activity in the vertebrate visual system. Neuron. 2009, 61: 895-905. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.018.

Smear MC, Tao HW, Staub W, Orger MB, Gosse NJ, Liu Y, Takahashi K, Poo Mm, Baier H: Vesicular glutamate transport at a central synapse limits the acuity of visual perception in zebrafish. Neuron. 2007, 53: 65-77. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.013.

Sajovic P, Levinthal C: Visual cells of zebrafish optic tectum: mapping with small spots. Neuroscience. 1982, 7: 2407-2426. 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90204-4.

Niell CM, Smith SJ: Functional imaging reveals rapid development of visual response properties in the zebrafish tectum. Neuron. 2005, 45: 941-951. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.047.

Meek J, Schellart NAM: A golgi study of goldfish optic tectum. J Comp Neurol. 1978, 182: 89-111. 10.1002/cne.901820107.

Scott EK, Baier H: The cellular architecture of the larval zebrafish tectum, as revealed by gal4 enhancer trap lines. Front Neural Circuits. 2009, 3: 13-10.3389/neuro.04.013.2009.

Scott EK, Mason L, Arrenberg AB, Ziv L, Gosse NJ, Xiao T, Chi NC, Asakawa K, Kawakami K, Baier H: Targeting neural circuitry in zebrafish using GAL4 enhancer trapping. Nat Methods. 2007, 4: 323-326.

Gosse NJ, Nevin LM, Baier H: Retinotopic order in the absence of axon competition. Nature. 2008, 452: 892-895. 10.1038/nature06816.

Heiligenberg W, Rose GJ: The optic tectum of the gymnotiform electric fish, Eigenmannia: labeling of physiologically identified cells. Neuroscience. 1987, 22: 331-340. 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90224-7.

Kinoshita M, Ito E, Urano A, Ito H, Yamamoto N: Periventricular efferent neurons in the optic tectum of rainbow trout. J Comp Neurol. 2006, 499: 546-564. 10.1002/cne.21080.

Meek J: Functional anatomy of the tectum mesencephali of the goldfish. An explorative analysis of the functional implications of the laminar structural organization of the tectum. Brain Res. 1983, 287: 247-297.

Meek J: A Golgi-electron microscopic study of goldfish optic tectum. I. Description of afferents, cell types, and synapses. J Comp Neurol. 1981, 199: 149-173. 10.1002/cne.901990202.

Sato T, Hamaoka T, Aizawa H, Hosoya T, Okamoto H: Genetic single-cell mosaic analysis implicates ephrinB2 reverse signaling in projections from the posterior tectum to the hindbrain in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2007, 27: 5271-5279. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0883-07.2007.

Cohen B, Buttner-Ennever JA: Projections from the superior colliculus to a region of the central mesencephalic reticular formation (cMRF) associated with horizontal saccadic eye movements. Exp Brain Res. 1984, 57: 167-176. 10.1007/BF00231143.

Herrero L, Pérez P, Núnez Abades P, Hardy O, Torres B: Tectotectal connectivity in goldfish. J Comp Neurol. 1999, 411: 455-471. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990830)411:3<455::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-7.

Herrero L, Rodríguez F, Salas C, Torres B: Tail and eye movements evoked by electrical microstimulation of the optic tectum in goldfish. Exp Brain Res. 1998, 120: 291-305. 10.1007/s002210050403.

Pérez-Pérez MP, Luque MA, Herrero L, Nuñez-Abades PA, Torres B: Connectivity of the goldfish optic tectum with the mesencephalic and rhombencephalic reticular formation. Exp Brain Res. 2003, 151: 123-135. 10.1007/s00221-003-1432-6.

Salas C, Herrero L, Rodriguez F, Torres B: Tectal codification of eye movements in goldfish studied by electrical microstimulation. Neuroscience. 1997, 78: 271-288. 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)83048-5.

Ramdya P, Engert F: Emergence of binocular functional properties in a monocular neural circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2008, 11: 1083-1090. 10.1038/nn.2166.

Clifford CWG, Ibbotson MR: Fundamental mechanisms of visual motion detection: models, cells and functions. Prog Neurobiol. 2002, 68: 409-437. 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00154-5.

Livingstone MS: Mechanisms of direction selectivity in macaque V1. Neuron. 1998, 20: 509-526. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80991-5.

Del Bene F, Wyart C, Robles E, Tran A, Looger L, Scott EK, Isacoff EY, Baier H: Filtering of visual information in the tectum by an identified neural circuit. Science. 2010

Bulina ME, Chudakov DM, Britanova OV, Yanushevich YG, Staroverov DB, Chepurnykh TV, Merzlyak EM, Shkrob MA, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA: A genetically encoded photosensitizer. Nat Biotechnol. 2006, 24: 95-99. 10.1038/nbt1175.

Roeser T, Baier H: Visuomotor behaviors in larval zebrafish after GFP-guided laser ablation of the optic tectum. J Neurosci. 2003, 23: 3726-3734.

Deeg KE, Sears IB, Aizenman CD: Development of multisensory convergence in the Xenopus optic tectum. J Neurophysiol. 2009, 102: 3392-3404. 10.1152/jn.00632.2009.

Hiramoto M, Cline HT: Convergence of multisensory inputs in Xenopus tadpole tectum. Dev Neurobiol. 2009, 69: 959-971. 10.1002/dneu.20754.

Pérez-Pérez MP, Luque MA, Herrero L, Nuñez-Abades PA, Torres B: Afferent connectivity to different functional zones of the optic tectum in goldfish. Vis Neurosci. 2003, 20: 397-410. 10.1017/S0952523803204053.

Sumbre G, Muto A, Baier H, Poo MM: Entrained rhythmic activities of neuronal ensembles as perceptual memory of time interval. Nature. 2008, 456: 102-106. 10.1038/nature07351.

Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K: Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron. 2008, 57: 634-660. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.002.

Chi NC, Shaw RM, Jungblut B, Huisken J, Ferrer T, Arnaout R, Scott I, Beis D, Xiao T, Baier H, Jan LY, Tristani-Firouzi M, Stainier DY: Genetic and physiologic dissection of the vertebrate cardiac conduction system. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6: e109-10.1371/journal.pbio.0060109.

Li J, Mack JA, Souren M, Yaksi E, Higashijima SI, Mione M, Fetcho JR, Friedrich RW: Early development of functional spatial maps in the zebrafish olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2005, 25: 5784-5795. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0922-05.2005.

Naumann EA, Kampff AR, Prober DA, Schier AF, Engert F: Monitoring neural activity with bioluminescence during natural behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2010, 13: 513-520. 10.1038/nn.2518.

Lundby A, Mutoh H, Dimitrov D, Akemann W, Knöpfel T: Engineering of a genetically encodable fluorescent voltage sensor exploiting fast Ci-VSP voltage-sensing movements. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3: e2514-10.1371/journal.pone.0002514.

Tsutsui H, Higashijima S, Miyawaki A, Okamura Y: Visualizing voltage dynamics in zebrafish heart. J Physiol. 2010, 588: 2017-2021. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189126.

Tsutsui H, Karasawa S, Okamura Y, Miyawaki A: Improving membrane voltage measurements using FRET with new fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2008, 5: 683-685. 10.1038/nmeth.1235.

Dreosti E, Odermatt B, Dorostkar MM, Lagnado L: A genetically encoded reporter of synaptic activity in vivo. Nat Methods. 2009, 6: 883-889. 10.1038/nmeth.1399.

Ng M, Roorda RD, Lima SQ, Zemelman BV, Morcillo P, Miesenböck G: Transmission of olfactory information between three populations of neurons in the antennal lobe of the fly. Neuron. 2002, 36: 463-474. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00975-3.

Yuste R, Miller RB, Holthoff K, Zhang S, Miesenbock G: Synapto-pHluorins: chimeras between pH-sensitive mutants of green fluorescent protein and synaptic vesicle membrane proteins as reporters of neurotransmitter release. Methods Enzymol. 2000, 327: 522-546. 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)27300-X.

Baier H, Scott EK: Genetic and optical targeting of neural circuits and behavior--zebrafish in the spotlight. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009, 19: 553-560. 10.1016/j.conb.2009.08.001.

Scott EK: The Gal4/UAS toolbox in zebrafish: new approaches for defining behavioral circuits. J Neurochem. 2009, 110: 441-456. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06161.x.

Szobota S, Gorostiza P, Del Bene F, Wyart C, Fortin DL, Kolstad KD, Tulyathan O, Volgraf M, Numano R, Aaron HL, Scott EK, Kramer RH, Flannery J, Baier H, Trauner D, Isacoff EY: Remote control of neuronal activity with a light-gated glutamate receptor. Neuron. 2007, 54: 535-545. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.010.

Wyart C, Bene FD, Warp E, Scott EK, Trauner D, Baier H, Isacoff EY: Optogenetic dissection of a behavioural module in the vertebrate spinal cord. Nature. 2009, 461: 407-410. 10.1038/nature08323.

Douglass AD, Kraves S, Deisseroth K, Schier AF, Engert F: Escape behavior elicited by single, channelrhodopsin-2-evoked spikes in zebrafish somatosensory neurons. Curr Biol. 2008, 18: 1133-1137. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.077.

Zhu P, Narita Y, Bundschuh ST, Fajardo O, Scharer YP, Chattopadhyaya B, Bouldoires EA, Stepien AE, Deisseroth K, Arber S, Sprengel R, Rijli FM, Friedrich RW: Optogenetic dissection of neuronal circuits in zebrafish using viral gene transfer and the Tet system. Front Neural Circuits. 2009, 3: 21-10.3389/neuro.04.021.2009.

Arrenberg AB, Del Bene F, Baier H: Optical control of zebrafish behavior with halorhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106: 17968-17973. 10.1073/pnas.0906252106.

Schoonheim PJ, Arrenberg AB, Del Bene F, Baier H: Optogenetic localization and genetic perturbation of saccade-generating neurons in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2010, 30: 7111-7120. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5193-09.2010.

May PJ: The mammalian superior colliculus: laminar structure and connections. Prog Brain Res. 2006, 151: 321-378. full_text.

Easter SS, Nicola GN: The development of vision in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Dev Biol. 1996, 180: 646-663. 10.1006/dbio.1996.0335.

Emran F, Rihel J, Dowling JE: A behavioral assay to measure responsiveness of zebrafish to changes in light intensities. J Vis Exp. 2008, 20: 923-

Kimmel CB, Patterson J, Kimmel RO: The development and behavioral characteristics of the startle response in the zebra fish. Dev Psychobiol. 1974, 7: 47-60. 10.1002/dev.420070109.

Kokel D, Bryan J, Laggner C, White R, Cheung CY, Mateus R, Healey D, Kim S, Werdich AA, Haggarty SJ, Macrae CA, Shoichet B, Peterson RT: Rapid behavior-based identification of neuroactive small molecules in the zebrafish. Nat Chem Biol. 2010, 6: 231-237. 10.1038/nchembio.307.

Kay JN, Finger-Baier KC, Roeser T, Staub W, Baier H: Retinal ganglion cell genesis requires lakritz, a Zebrafish atonal Homolog. Neuron. 2001, 30: 725-736. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00312-9.

Neuhauss SCF, Biehlmaier O, Seeliger MW, Das T, Kohler K, Harris WA, Baier H: Genetic disorders of vision revealed by a behavioral screen of 400 essential loci in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 1999, 19: 8603-8615.

Emran F, Rihel J, Adolph AR, Dowling JE: Zebrafish larvae lose vision at night. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010, 107: 6034-6039. 10.1073/pnas.0914718107.

Li L, Dowling JE: Zebrafish visual sensitivity is regulated by a circadian clock. Vis Neurosci. 1998, 15: 851-857.

Brockerhoff SE, Hurley JB, Janssen-Bienhold U, Neuhauss SCF, Driever W, Dowling JE: A behavioral screen for isolating zebrafish mutants with visual system defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995, 92: 10545-10549. 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10545.

Burgess HA, Schoch H, Granato M: Distinct retinal pathways drive spatial orientation behaviors in zebrafish navigation. Curr Biol. 2010, 20: 381-386. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.022.

Orger MB, Baier H: Channeling of red and green cone inputs to the zebrafish optomotor response. Vis Neurosci. 2005, 22: 275-281. 10.1017/S0952523805223039.

Maximino C, Marques de Brito T, Dias CA, Gouveia A, Morato S: Scototaxis as anxiety-like behavior in fish. Nat Protoc. 2010, 5: 209-216. 10.1038/nprot.2009.225.

Nicolson T, Rusch A, Friedrich RW, Granato M, Ruppersberg JP, Nusslein-Volhard C: Genetic analysis of vertebrate sensory hair cell mechanosensation: the zebrafish circler mutants. Neuron. 1998, 20: 271-283. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80455-9.

Beck JC, Gilland E, Tank DW, Baker R: Quantifying the ontogeny of optokinetic and vestibuloocular behaviors in zebrafish, medaka, and goldfish. J Neurophysiol. 2004, 92: 3546-3561. 10.1152/jn.00311.2004.

Rinner O, Rick JM, Neuhauss SCF: Contrast sensitivity, spatial and temporal tuning of the larval zebrafish optokinetic response. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005, 46: 137-142. 10.1167/iovs.04-0682.

Bilotta J: Effects of abnormal lighting on the development of zebrafish visual behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2000, 116: 81-87. 10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00264-3.

Orger MB, Kampff AR, Severi KE, Bollmann JH, Engert F: Control of visually guided behavior by distinct populations of spinal projection neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2008, 11: 327-333. 10.1038/nn2048.

Orger MB, Smear MC, Anstis SM, Baier H: Perception of Fourier and non-Fourier motion by larval zebrafish. Nat Neurosci. 2000, 3: 1128-1133. 10.1038/80649.

Dill LM: The escape response of the zebra danio (Brachydanio rerio). I. The stimulus for escape. Anim Behav. 1974, 22: 711-722. 10.1016/S0003-3472(74)80022-9.

Li L, Dowling JE: A dominant form of inherited retinal degeneration caused by a non-photoreceptor cell-specific mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 11645-11650. 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11645.

Borla MA, Palecek B, Budick S, O'Malley DM: Prey capture by larval zebrafish: evidence for fine axial motor control. Brain Behav Evol. 2002, 60: 207-229. 10.1159/000066699.

Budick SA, O'Malley DM: Locomotor repertoire of the larval zebrafish: swimming, turning and prey capture. J Exp Biol. 2000, 203: 2565-2579.

Gahtan E, Tanger P, Baier H: Visual prey capture in larval zebrafish is controlled by identified reticulospinal neurons downstream of the tectum. J Neurosci. 2005, 25: 9294-9303. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2678-05.2005.

Bass SLS, Gerlai R: Zebrafish (Danio rerio) responds differentially to stimulus fish: the effects of sympatric and allopatric predators and harmless fish. Behav Brain Res. 2008, 186: 107-117. 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.037.

Gerlai R, Fernandes Y, Pereira T: Zebrafish (Danio rerio) responds to the animated image of a predator: towards the development of an automated aversive task. Behav Brain Res. 2009, 201: 318-324. 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.003.

Engeszer RE, Ryan MJ, Parichy DM: Learned social preference in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2004, 14: 881-884. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.042.

Engeszer RE, Wang G, Ryan MJ, Parichy DM: Sex-specific perceptual spaces for a vertebrate basal social aggregative behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008, 105: 929-933. 10.1073/pnas.0708778105.

McCann LI, Koehn DJ, Kline NJ: The effects of body size and body markings on nonpolarized schooling behavior of zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio). J Psychol. 1971, 79: 71-75. 10.1080/00223980.1971.9923769.

Miller N, Gerlai R: Quantification of shoaling behaviour in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Behav Brain Res. 2007, 184: 157-166. 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.007.

Saverino C, Gerlai R: The social zebrafish: behavioral responses to conspecific, heterospecific, and computer animated fish. Behav Brain Res. 2008, 191: 77-87. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.013.

Turnell ER, Mann KD, Rosenthal GG, Gerlach G: Mate choice in zebrafish (Danio rerio) analyzed with video-stimulus techniques. Biol Bull. 2003, 205: 225-226. 10.2307/1543265.

Huang YY, Tschopp M, Neuhauss SCF: Illusionary self-motion perception in zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2009, 4: e6550-10.1371/journal.pone.0006550.

Rick JM, Horschke I, Neuhauss SCF: Optokinetic behavior is reversed in achiasmatic mutant zebrafish larvae. Curr Biol. 2000, 10: 595-598. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00495-4.

Nevin LM, Taylor MR, Baier H: Hardwiring of fine synaptic layers in the zebrafish visual pathway. Neural Dev. 2008, 3: 36-10.1186/1749-8104-3-36.

Kay JN, Link BA, Baier H: Staggered cell-intrinsic timing of ath5 expression underlies the wave of ganglion cell neurogenesis in the zebrafish retina. Development. 2005, 132: 2573-2585. 10.1242/dev.01831.

Masai I, Lele Z, Yamaguchi M, Komori A, Nakata A, Nishiwaki Y, Wada H, Tanaka H, Nojima Y, Hammerschmidt M, Wilson SW, Okamoto H: N-cadherin mediates retinal lamination, maintenance of forebrain compartments and patterning of retinal neurites. Development. 2003, 130: 2479-2494. 10.1242/dev.00465.

Zolessi FR, Poggi L, Wilkinson CJ, Chien CB, Harris WA: Polarization and orientation of retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Neural Dev. 2006, 1: 2-10.1186/1749-8104-1-2.

Pittman AJ, Law MY, Chien CB: Pathfinding in a large vertebrate axon tract: isotypic interactions guide retinotectal axons at multiple choice points. Development. 2008, 135: 2865-2871. 10.1242/dev.025049.

Wagner HJ, Wagner E: Amacrine cells in the retina of a teleost fish, the roach (Rutilus rutilus): a Golgi study on differentiation and layering. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1988, 321: 263-324. 10.1098/rstb.1988.0094.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our laboratory for discussions. Work in the authors' laboratory was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the March of Dimes Foundation, NARSAD and HFSP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nevin, L.M., Robles, E., Baier, H. et al. Focusing on optic tectum circuitry through the lens of genetics. BMC Biol 8, 126 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-8-126

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-8-126