Abstract

Background

Evolution of the deuterostome lineage was accompanied by an increase in systematic complexity especially with regard to highly specialized tissues and organs. Based on the observation of an increased number of paralogous genes in vertebrates compared with invertebrates, two entire genome duplications (2R) were proposed during the early evolution of vertebrates. Most glycolytic enzymes occur as several copies in vertebrate genomes, which are specifically expressed in certain tissues. Therefore, the glycolytic pathway is particularly suitable for testing theories of the involvement of gene/genome duplications in enzyme evolution.

Results

We assembled datasets from genomic databases of at least nine vertebrate species and at least three outgroups (one deuterostome and two protostomes), and used maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods to construct phylogenies of the 10 enzymes of the glycolytic pathway. Through this approach, we intended to gain insights into the vertebrate specific evolution of enzymes of the glycolytic pathway. Many of the obtained gene trees generally reflect the history of two rounds of duplication during vertebrate evolution, and were in agreement with the hypothesis of an additional duplication event within the lineage of teleost fish. The retention of paralogs differed greatly between genes, and no direct link to the multimeric structure of the active enzyme was found.

Conclusion

The glycolytic pathway has subsequently evolved by gene duplication and divergence of each constituent enzyme with taxon-specific individual gene losses or lineage-specific duplications. The tissue-specific expression might have led to an increased retention for some genes since paralogs can subdivide the ancestral expression domain or find new functions, which are not necessarily related to the original function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

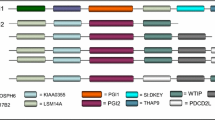

In many cases, evolution is accompanied by an increase of genetic and phenotypic complexity, yet the biochemical machinery necessary for the energy supply of an increasing diversity of cell- and tissue types had to work effectively, even if different tissues have specific conditions such as pH values, ion and substrate concentrations. Based on basic data such as genome sizes and allozymes, Ohno [1] proposed that the increase in complexity-during the evolution of the vertebrate lineage was accompanied by an increase in gene number due to duplication of genes and/or genomes. Recent data from genome sequencing projects showed that genome size is not strongly correlated with the numbers of genes an organism possesses. Nevertheless, for many genes, multiple copies can be found in vertebrates, while basal deuterostomes and invertebrates typically have only one orthologous copy. The "one-two-four" rule is the current model to explain the evolution of gene families and of vertebrate genomes more generally (Figure 1). Based on this model, two rounds of genome duplication occurred early in the vertebrate evolution [2, 3], but see also [4, 5]. An ancestral genome was duplicated to two copies after the first genome duplication (1R), and then to four copies after the second (2R) duplication [6, 7]. While it is commonly accepted that 1/2R occurred before the divergence of Chondrichthyes [8], the position of lamprey and hagfish relative to the 1R still remains unclear, even though there is some evidence for a 1R-early (before divergence of cyclostomes) [9]. Recent data suggest that an additional whole genome duplication occurred in the fish lineage (3R or fish-specific genome duplication, extending the "one-two-four" to a "one-two-four-eight" rule [10–16].

General overview of phylogenetic relationships among gnathostomes and the proposed phylogenetic timing of genome duplication events. Grey rectangles depict the possible position of the first genome duplication (1R); the black ones show the second genome duplication (2R), and fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD or 3R).

Duplicated genes, resulting from large scale duplications, initially possess the same regulatory elements and identical amino-acid sequence and are therefore thought to be redundant in their function, which means that inactivation of one of the two duplicates should have little or no effect on the phenotype, provided that there are no dosage compensation effects [17]. Therefore, since one of the copies is free from functional constraint, mutations in this gene might be selectively neutral and will eventually turn the gene into a non-functional pseudogene. Although gene loss is a frequent event, 20–50% of paralogous genes are retained for longer evolutionary time spans after a genome duplication event [18, 19]. On the other hand, a series of non-deleterious mutations might change the function of the duplicate gene copy [20]. Natural selection can prevent the loss of redundant genes [21] if those genes code for components of multidomain proteins, because mutant alleles disrupt such proteins. A selective advantage due to a novel function might be sufficient to retain this gene copy and to select against replacement substitutions and prevent this functional gene copy from turning into a pseudogene. In this way, genes can pick up new functions (neofunctionalization) [6] or divide the ancestral function between the paralogs (subfunctionalization) [22].

The glycolytic pathway is particularly suitable for testing theories of enzyme evolution and the involvement of gene/genome duplications. Previous phylogenetic analyses of these enzymes mainly focused on deep phylogenies [23, 24] or the evolution of alternative pathways in different organisms, which displays high variability in bacteria [25, 26]. This central metabolic pathway is highly conserved and ancient; it is therefore possible to compare enzymes from phylogenetically distant organisms [27]. The standard pathway includes 10 reaction steps; glucose is processed to pyruvate with the net yield of two molecules of adenosine triphosphate and two reduced molecules of hydrogenated nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide per molecule of glucose broken down. The classical glycolytic reactions are catalyzed by the following 10 enzymes: hexokinase (HK; EC 2.7.1.1), phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI; EC 5.3.1.9), phosphofructokinase (PFK; EC 2.7.1.11), fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA; EC 4.1.2.13); triosephosphate isomerase (TPI; EC 5.3.1.1), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; EC 1.2.1.12), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK; EC 2.7.2.3), phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM; EC 5.4.2.1), enolase (ENO; EC 4.2.1.11), and pyruvate kinase (PK; EC 2.7.1.40) [28].

The tertiary structures of all 10 of these enzymes show a superficial similarity; they are all variations on a common theme [27]. All glycolytic enzymes belong to the class of α/β-barrel proteins. Since this pathway is of crucial importance for the energy delivery of any cell, these genes are thought to be highly conserved and therefore have often been used as phylogenetic markers for "deep" phylogenies [23, 29, 30]. In fact, glycolytic enzymes are probably among the most conserved proteins known. Many vertebrate genes occur in multiple copies in the genome, and are often expressed in a tissue-specific manner. This increased genetic complexity might be utilized for highly specific requirements in terms of substrate optimum, pH value and salt concentration in different types of tissues [31]. Glucokinase, one of the hexokinase isozymes, is expressed in the liver and the pancreas, and requires a high concentration of glucose to reach the maximum turnover rate. As a result of this, high glucose levels after food uptake are reduced by the production of glycogen in the liver [32]. The other hexokinase isozymes work with much lower substrate concentrations.

The main goal of the present work was to contribute to an evolutionary understanding of glycolysis by phylogenetic analyses of the 10 glycolytic enzymes from representatives of the vertebrate lineage. Based on the observation of increased size of gene families in vertebrates [10, 33–40] and their highly specialized tissues, we expected to find duplications of entire pathways in the vertebrate lineage.

Results

For most glycolytic enzymes, two or more copies can be found in vertebrates. The topologies for the inferred gene trees generally reflect the history of one or two rounds of duplications within the vertebrate lineage plus an additional duplication event within the teleost fish. The phylogenetic analyses confirm duplication events leading to multiple copies within vertebrates; these duplications occurred almost invariantly after the divergence of the urochordate C. intestinalis (Figures 2B, 2C, 3B, 4A, 4B, 5A, 5C)

Maximum-likelihood tree of the tetrameric glycolytic enzymes phosphofructokinase (PFK), glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and pyruvate kinase (PK) dataset comprising 44 amino-acid sequences for PFK (430 AA), 22 amino-acid sequences for GAPDH (340 AA), and 23 amino-acid sequences for PK (533 AA). Values at the branches are support values (ML bootstrapping/MB posterior probabilities). "FSGD" depicts putative fish-specific gene duplication events.

Maximum-likelihood tree of the heterodimeric composing glycolytic enzymes enolase (ENO), and phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM) dataset comprising 40 amino-acid sequences for ENO (446 AA), and 32 amino-acid sequences for PGAM (256 AA). Values at the branches are support values (ML bootstrapping/MB posterior probabilities). 'FSGD' depicts putative fish-specific gene duplication events.

Maximum-likelihood tree of the homodimeric composing glycolytic enzymes phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI), and triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) dataset comprising 22 amino-acid sequences for PGI (555 AA), and 16 amino-acid sequences for TPI (250 AA). Values at the branches are support values (ML bootstrapping/MB posterior probabilities). 'FSGD' depicts putative fish-specific gene duplication events.

Maximum-likelihood trees of the monomeric glycolytic enzymes hexokinase (HK), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA) dataset comprising 44 amino-acid sequences for HK (909 AA), 15 amino-acid sequences for PGK (417 AA), and 47 amino-acid sequences for FBA (366 AA). Values at the branches are support values (ML bootstrapping/MB posterior probabilities). 'FSGD' depicts putative fish-specific gene duplication events.

Tetrameric enzymes

Glycolytic enzymes, which are active as tetramers, occur as 1–4 copies in vertebrate genomes, likely as a result of ancient genome duplication events (1R and 2R). They display clearly different evolutionary patterns (Figure 2).

The tree for PFK reflects a perfect 1R/2R topology with three additional 3R events in the liver-specific isoform PFK1, the muscle-specific PFK2, and the platelet isoform PFK4 (Figure 2A). The first duplication led to PFK1/4 and PFK2/3 gene pairs (1R). The second duplication event segregates these precursors into the extant genes (2R). Except for PFK3, all PFK isoforms occur in more than one copy in ray-finned fishes (3R). However, for Danio rerio, searches of genomic and expressed sequence tag (EST) data yielded no second PFK1, PFK2 and PFK4 paralog as in the pufferfishes, where there is strong support for 3R. Since the Danio rerio genome is currently in a rather fragmented and incomplete state, the chances of missing data are quite high. On the other hand, the possibility of gene loss in certain lineages also cannot be neglected. Reciprocal loss of genes has been proposed as a mechanism for speciation [41].

The duplication of GAPDH seems to have occurred before the evolution of the bilaterian animals (Figure 2B). The liver-specific GAPDH (in vertebrates [42]) is found in all bilaterian species included in this analysis, whereas the testis-specific form occurs only in vertebrates. The tree topology of the liver-specific form reflects the general bilaterian phylogeny only in parts, most likely due to the sparse taxon sampling. Notably, the monophyly of protostomes and in particular the ecdysozoans is not recovered, since the two distinct copies of Caenorhabditis were placed as a sister group to the deuterostomes, albeit without significant support. For Xenopus, BLAST searches of genomic and EST data yielded no GAPDH copy.

The phylogeny of PK shows only one duplication event within the vertebrate lineage with an additional clearly resolved fish-specific duplication event, which occurred in the blood-specific [43] form PK1 (Figure 2C).

Heterodimeric enzymes

The topologies for the obtained gene trees of ENO and PGM reflect the history of 1R/2R/3R (Figure 3). We obtained full-length ENO cDNA sequences for two genes each from bichir (Polypterus senegalus) and sturgeon (Acipenser baerii), both basal ray-finned fish, and caecilian (Typhlonectes natans). Database searches revealed three copies of ENO within the vertebrates (Figure 3A). The sequences of lampreys and hagfish cluster with the ENO γ paralogous group, implying that the first duplication (1R) took place before the split of cyclostomes from the gnathostome lineage, as it has also been indicated by a study on Hox genes [9]. The positions of another lamprey sequence is basal to the multiple copies, possibly a long-branch attraction artifact, pulling this fast-evolving sequence towards the outgroup. The liver-specific ENO α is duplicated in actinopterygians, with a proposed timing of the duplication before the divergence of Polypterus and Acipenser. The bootstrap support for this topology, which contradicts the current view of the fish-specific duplication being limited to teleosts, [44–46] is low. For Acipenserformes, however, polyploidy is a known phenomenon [47]. One fish-specific paralog displays an increased rate, especially in Takifugu rubripes. The differences in amino-acid sequence are distributed over the complete sequence and cannot be linked to a specific functional domain. The same is true for all three teleost ENO γ sequences used in this study.

The topology for PGAM reflects the well-supported history 2R/3R in the brain isoform PGAM1 and an additional gene duplication within the human lineage (Figure 3B). The first duplication led to erythrocyte-specific bisphophoglycerate mutase (BGAM) and the precursor of PGM1 and PGM2; the latter is assumed to be a muscle-specific isoform [48].

Homodimeric enzymes

Within PGI and TPI, the major phylogenetic relationships are in agreement with the widely accepted phylogeny of vertebrates (Figure 4). Based on the phylogenetic analyses, duplication events leading to multiple copies within vertebrates could not be shown. However, there were duplication events during the evolution of ray-finned fish, so there are two copies each in zebrafish, puffer fishes, medaka, striped mullet and trout for PGI (Figure 4A), and two copies in zebrafish, platyfish and one pufferfish (Tetraodon nigroviridis) for TPI (Figure 4B), respectively. No second TPI paralog in Takifugu rubripes could be found within genomic and EST databases, which might indicate an event of gene loss.

Enzymes only active as monomers

Figure 5 shows the ML trees of monomeric enzymes obtained in the phylogenetic analyses on the amino-acid level. Based on the phylogenetic analyses, duplication events leading to multiple copies during vertebrate evolution could be detected. The topology for HK shows three rounds of duplication within the vertebrate lineage, which is not in agreement with our expectations. An additional duplication event happened within the lineage of ray-finned fish in the brain isoform, HK1 (Figure 5A). The first duplication led to HK4 (glucokinase), a 50-kDa enzyme, and the protoortholog of HK1, 2, 3 (all 100 kDa). The second duplication produced HK3, which shows a somewhat higher rate of evolution than the other isoforms, and a HK1/2 precursor, which gave rise to HK1 and HK2 in a subsequent gene duplication that most likely occurred in a gnathostome ancestor (2R). Zebrafish paralogs for HK1 and HK 3 could not be found in the last version of the Ensembl database (WTSIZv5). Thus, the timing of duplication events within the ray-finned fish in HK1 cannot be determined, and the duplication might be limited to pufferfish species.

The analyses revealed a mammal specific duplication event for PGK (Figure 5B). They possess a testis-specific isoform (PGK2) and a liver-specific isoform (PGK1). The position of the wallaby sequence implies that the duplication occurred before the divergence of placental mammals and marsupials.

Based on the phylogenetic analyses, the FBA duplication events leading to the multiple copies within vertebrates occurred clearly after the divergence of the lampreys (Figure 5C), which suggests a timing of the 1R/2R after the cyclostome split (but see the ENO tree, Figure 3B). The brain-specific isoform FBA C and the muscle-specific isoform FBA A show additional duplication events within the ray-finned fish lineage. For FBA C within the teleosts, a duplication preceding the split of Polypterus and Acipenser is proposed; this is not in agreement with the current hypothesis of the timing of the FSGD [44–46]. The unexpected topology is probably caused by a reconstruction artifact due to the very fast-evolving sequences of one of the fish-specific copies. A study based on yeast paralogs has shown that an increased evolutionary rate of one copy can lead to errors in phylogenetic reconstruction [49]. The differences in the sequences are distributed over the complete coding sequences and not restricted to a specific domain. The remaining sequences do resemble the general expectations of vertebrate phylogenetic relationships [50]. We also obtained FBA sequences for Acipenser baerii and Polypterus senegalus that clustered in the paralog A group, which is considered to be the muscle-specific isoform. One additional copy of FBA A in Danio rerio placed basal to the zebrafish/pufferfish split rejects the possibility of a zebrafish-specific duplication event. The Typhlonectes natans (caecilian) sequence (FBA A) forms a monophyletic group with the sequences from the Xenopus species, as expected. The FBA B isoform places the basal ray-finned fish (Acipenser baerii, Polypterus ornatipinnis) basal to a cluster containing tetrapods and derived ray-finned fish (Danio rerio, Tetraodon nigroviridis). This might be due to the partial character of these sequences, which were used from a previous study [29].

Discussion

The individual glycolytic enzymes are among the most slowly evolving genes [51], yet the glycolytic pathway has adapted to the varying metabolic requirements of different tissues and different organisms. Genome duplications appear to have been the principal mechanism that gives rise to multiple copies of isoenzymes. The topologies for eight of the gene trees (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5) generally reflect the 1R/2R/3R genome duplication history during vertebrate evolution. Convincing data supporting the 2R hypothesis stems from paralogons, genomic regions containing paralogous genes and therefore being the result of large-scale duplications [52–54]. Only some of the glycolytic enzymes showing 1R/2R duplications are found on chromosomes where paralogons have been previously reported, i.e., PK (PK3 on chromosome 15, PK1 on chromosome 1), ENO (ENOα on chromosome 1, ENOβ on chromosome 17, ENOγ on chromosome 12), HK (HK1 on chromosome 10, HK2 on chromosome 2, HK3 on chromosome5), and FBA (FBAA on chromosome 16, FBAC on chromosome 17).

For many single-copy genes in tetrapods, two copies have been described for ray-finned fish. The first observation of this pattern began with the discovery of more than four Hox clusters in zebrafish (Danio rerio) [55] and medaka (Oryzias latipes) [56]. Recent data from puffer-fish genomes confirmed the existence of at least seven Hox clusters even in these very compact genomes [57, 58]. With an increase of available sequences, especially from genome and EST projects, the number of genes which show a duplication event in the fish lineage increased significantly [10–12, 15, 34, 38, 59–61]. Data from the genes analyzed in this study, including genomic sequences (Tetraodon nigroviridis, Takifugu rubripes) and EST data (Danio rerio), shows that enzyme isoforms were duplicated before the divergence of Ostariophysii (zebrafish) and Neoteleostei (medaka, pufferfishes). The determination of the phylogenetic timing of the duplication event for glycolytic genes is difficult due to missing sequence data for basal actinopterygian species (bichir, sturgeon, gar and bowfin). Also, in many cases a strikingly increased evolutionary rate of at least one copy of the duplicated genes might result in a basal position of this paralogous cluster via LBA artifacts ("outgroup tree topology"). [49, 62] rendering the phylogenetic reconstruction of the ancient events (~400-350 MYA) difficult [63]. Previous studies have shown that the most likely position of the 3R genome duplication event is after the divergence of gar/bowfin (Holostei) from the teleost lineage [44–46].

Hexokinase

Glycolytic enzymes are often expressed in a tissue-specific manner. For example, the different types of vertebrate HK (Figure 5A), each with distinct kinetic properties, are expressed in different kinds of tissue. HK 1 is the predominant isoenzyme in the vertebrate brain, HK 2 predominates in muscle tissue, and HK 4 in hepatocytes and pancreatic islets. The kinetic properties of these three isoenzymes are well adapted to the roles of glucose phosphorylation in the different cell types [64]. Both HK 1 and HK 2 are saturated at glucose concentrations in the normal physiological range for blood, and thus their kinetic activity is largely unaffected by variations. When the availability of glucose is pathologically low, it is more important to satisfy the glucose needs of the brain than those of other tissues, and a low Km of HK 1 allows it to perform at low glucose concentrations. The kinetic behavior of HK 4, which requires high concentrations of glucose for maximal activity, is very different, but this is in agreement with functions in liver and pancreas cells as regulators of blood-glucose concentration [65, 66]. The function of HK 3 is inhibited by excess glucose [67], the reason for this is still not fully understood.

Based on the phylogeny reconstructed here (Figure 5A) as well as previous reports [64], HK 4 is the oldest member of this gene family. HK 4 consists of a 50-kDa fragment, whereas the other HKs have a size of 100 kDa. A more detailed analysis with separately considered amino and carboxy termini suggests that a fusion event led to the present isoenzymes [64]. We were also able to document a fish-specific duplication of HK 1, however, nothing is known about possible functional consequences due to their duplication in terms of sub- or neofunctionalization.

Phosphoglucose isomerase

PGI is a multifunctional protein, also known as neuroleukin (NLK), autocrine mobility factor (AMF), or differentiation and maturation mediator. Although it was proposed that the multiple functions of PGI were gained gradually by amino-acid changes [68], an alternative hypothesis is that PGI is recruited by other proteins for novel functions during evolution [69]. Two lines of evidence support this hypothesis. First, the protein is highly constrained, and second, Bacillus PGI not only can replace the glycolytic aspects of the enzyme, but also fulfil NLK and AMF functions in mammalian cells[70, 71]. The multiple functions were proposed to be innate characteristics of PGI at the origin of the protein [69]. The novel functions of PGI might have evolved by cellular compartmentalization of the protein, dimerization, and evolution of its receptors. The enzyme is found to be active as a dimer in glycolysis. It is not clear whether it is active in its other functions as a monomer or as an oligomer. This multi-functionality and the possible function as an oligomer might explain the retention of two copies in the fish lineage. The topology (Figure 4A) suggests that the only gene-duplication event of PGI occurred in ray-finned fish before the diversification of Acanthopterygii but after the split of ray-finned fish and tetrapods.

Phosphofructokinase

The PFK gene family is composed of four different genes (Figure 2A): They are expressed in liver (PFK1), muscle (PFK2), brain (PFK3) and platelets (PFK4) [27]. These genes differ both in size and physico-chemical properties, and are also expressed in varying amounts in different tissues. PFK occurs in a variety of oligomeric forms from dimer to tetramer to octamer and even larger forms. The vertebrate enzyme, however, is active as a tetramer. Because the subtypes can associate randomly, each tissue contains not only homotetrameric enzymes, but also various types of heterotetramers. These different assemblies of subunits result in complex isoenzymic populations with a wide variety of kinetic properties [72]. It seems likely that the copies result from 2R. The number of possibilities of PFK combinations in ray-finned fish is even higher because of 3R (PFK1, PFK2, PFK4). The functional significance of the complicated quaternary structure of PFK is not entirely clear, but probably relates to the requirement for specific responsive control properties for this enzyme. A wide range of effector molecules have been described [73–75], and some forms of the enzyme can be also regulated by phosphorylation [76–78].

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase

The three FBA isoenzymes A, B, C in vertebrates [79] also have a tissue-specific distribution [80, 81]. FBA A, which is the most efficient in glycolysis, is the major form present in muscle. FBA B seems to function in gluconeogenesis and is only expressed in liver and kidney, where it is the predominant form. FBA C, with intermediate catalytic properties, is found in the brain. In the FBA tree (Figure 5C), the lamprey sequences preceded the first duplication, while the Agnatha clade in the ENO analyses (Figure 3A) clusters with one branch of the duplication. Statistical support for the nodes around 2R and the divergence of cyclostomes, however, is high. Multiple sequences from Chondrostei (sharks and rays) for FBA, which are clearly grouped with the three paralogous groups, suggest a timing of the duplications before their separation from the Osteichthyes lineage. Within the fish lineage, FBA A was duplicated before the divergence of Ostariophysii (zebrafish) and Neoteleostei (medaka, pufferfish). However, in the FBA C subtree, gar and bichir are grouped within one paralogous group. Either one paralogous copy for gar and bichir of this gene has not been found yet, or this reconstruction is due to a reconstruction artifact caused by the extremely fast-evolving sequences of the teleost sequences (zebrafish and pufferfishes), which get drawn to the basis (LBA).

Triosephosphate isomerase

TPI is highly conserved in sequence, structure, and enzymatic properties [82]. The enzyme is functional as a homodimer. The topology (Figure 4B) suggests that the only gene-duplication event of TPI occurred in ray-finned fish before the diversification of Acanthopterygii but after the split of ray-finned fish and tetrapods. This corroborates the results of a previous study [83] supporting a single gene duplication event early in the evolution of ray-finned fish. Comparisons between inferred ancestral TPI sequences indicated that the neural TPI isozyme evolved through a period of positive selection, resulting in the biased accumulation of negatively charged amino acids. If both copies are coexpressed, TPI could act as heterodimer in fish with consequences in specificity or enzyme kinetics.

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

GAPDH is the most highly conserved of all glycolytic enzymes. The rate of evolution of the catalytic domain, for example, is only 3% per 100 million years [27]. Thus, these domains in eukaryotic and eubacterial enzymes are >60% identical. Due to this constraint we had to include basal animal lineages (arthropods, flatworms, nematodes and mollusks) into the analysis to clearly identify the origins of two copies of GAPDH (Figure 2B). The GAPDH acts as a tetramer, however, it is not clear whether this is constituted out of two different isoenzymes in vertebrates similar to the PFK composition. There is evidence for an ancient duplication around the bilaterian origin; however, the testis-specific copy was found only in vertebrates, which makes this scenario rather unlikely. It has been hypothesized that vertebrates acquired a second copy, only expressed in the testis, by retroposition [84, 85]. However, many more new gene copies were created, most of which, if not all, seem to be pseudogenes [42, 86, 87]. This might be also the case for the muscle-specific form, which only occurs in primates. Despite the possibility of requiring variability by composing heterotetramers with additional isoenzymes, it is also possible that paralogs are retained because GAPDH is also involved in the maintenance of specific subcellular structures, e.g. the bundling of microtubules [88].

Phosphoglycerate kinase

The quaternary structure of most glycolytic enzymes has been well conserved during evolution. Monomeric forms are unusual, and one enzyme that is invariably a monomer is phosphoglycerate kinase. In mammals, two different, but functionally similar isoenzymes for phosphoglycerate kinase have been detected. One form occurs in all somatic cells predominantly in the liver. The other form is only found in sperm cells [89]. The gene for the major isoenzyme (pgk1) is X-linked. Expression of this gene coincides with overall activity of the X chromosome. Its transcription is thus constitutive, regardless of the cell type, when the chromosome is active. When spermatogenic cells enter meiosis, the X chromosome is inactivated and the second gene (pgk2), which is autosomal (chromosome 6 in humans), is expressed [90]. It has been proposed that the pgk2 gene, which does not contain any introns in contrast to pgk1, must have evolved from the pgk1 gene by retroposition [89, 91]. Our phylogenetic analysis suggests that this must have happened early in mammalian evolution (Figure 5B). Although weakly supported, the position of the wallaby sequence (Macropus eugenii) implies that the duplication occurred before the divergence of placental mammals and marsupials.

Phosphoglycerate mutase

In the cofactor-dependent PGAM gene family, three paralogs can be found in all vertebrates. These isoenzymes are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and have been classified as brain (PGAM1), muscle (PGAM2) and erythrocyte (BGAM) types. In some tissues, more than one gene is active, resulting in multiple isoenzymes composed of homo- and heterodimers [92]. The phylogenetic analyses (Figure 3B) shows that the three isoenzymes found in vertebrates have evolved from a common ancestor by two separate gene-duplication events. A PGAM3 form was proposed in human and chimp [93], probably as a result of primate-specific gene duplication. Our findings suggest that a more recent duplication gave rise to the PGAM1 and PGAM2 copies. BLAST searches against the chicken genome detected only the PGAM1 form. This could be explained by gene loss of the PGAM2 gene in the avian line, or by the incompleteness of the genome assembly. In our phylogeny, the origin of PGAM predates the PGAM1 and PGAM2 divergence. This clarifies uncertainties of previous studies in unravelling the evolutionary history of PGAM [27, 48]. Vertebrate PGMs are rather versatile and can catalyze three different reactions (they act as mutase, synthase or phosphatase). Initially it was supposed that each of these reactions was catalyzed by a different enzyme, and it was quite surprising when it was realized that the PGM could each catalyze all three of these reactions, albeit at substantially different rates [94]. One can speculate that these differences in activity rates acted in favor of the maintenance of several copies during evolution.

Enolase

For ENO three different isoenzymes also occur in vertebrate tissues, termed α, β and γ. The active enzyme is a homo- or heterodimer. The α form is present in many tissues, especially in the liver, β predominates in muscle and γ is only found in brain cells. The topologies for the gene tree generally reflect the history of 2R/3R for ENO α (Figure 3A). However, the position of the Cyclostomata sequences is not consistent and therefore offers no information about the relative timing of the duplication events. One lamprey sequence precedes the first duplication, while the Agnatha clade in the ENO β analyses clusters with one branch of the duplication, however, there is very little support. This is not in agreement with the current hypothesis of the relative timing of 2R [9]. Two functions have been attributed to ENO in addition to its normal catalytic activity. First, ENO plays a structural role in the eye lens. A major lens protein of lampreys, some fishes and birds is τ-cristallin. This protein and α-ENO appear to be identical [95–97]. The additional duplication within the fish lineage in ENO α might provide a bigger "toolbox" for this gene's function while retaining its glycolytic pathway role simultaneously. The additional role that ENO may fulfill is the acquisition of thermal tolerance [98]. The Enolase genes are positioned in well described paralogons of the human genome on chromosomes 1 (ENO α), 17 (ENO β) and 12 (ENO γ) [53], This implies that they are resulting from a large-scale duplication event, probably a genome duplication.

Pyruvate kinase

It was originally expected that PK had four different isoforms encoded by four different genes. However, it is known now that there are only two different genes: one encoding the PK3 (m-form) isoforms and one for the PK1 (l and r forms) isoenzymes. Additional isoenzymes can arise from differential RNA splicing. Therefore, the phylogeny (Figure 2C) is only considering one gene product for each isoenzyme. The differences between the spliced isoforms are too small to include into a phylogenetic analysis. Both copies seem to be derived from a duplication event in early vertebrate history (1R or 2R) and are expressed in a tissue-specific manner. PK1 is the most abundant form in liver, where gluconeogenesis plays an important role [99]. PK3 is the major form in tissues, where glycolysis predominates such as muscle, heart and brain. Both isoenzymes show different enzyme kinetics according to their occurrence. The PK is active as a tetramer, which is regulated by the thyroid hormone and fructose 1,6-bisphosphate [100, 101]. Usually PK is active as homotetramer but in some cases, it also acts as a heterotetramer. This might be an explanation for why the copies of the fish-specific duplication in PK1 were retained during evolution. As shown previously, the increase in possible combinations of heterotetramers leads to increased specificity in enzyme kinetics.

Conclusion

From our data, we could not detect a 1R/2R/3R trend consistent for all enzymes of the glycolytic pathway. Even though most of them do show a repeated pattern of duplications, which are accompanied by tissue-specific expression, this is not the case for all of them. Considerations of tertiary protein structure also could not give further indications for why some enzymes have four isozymes in tetrapods and others only one. Given the expectation that most genes get lost rather rapidly after a duplication event [17, 18], the tissue-specific expression might have led to an increased retention for some genes since paralogs can subdivide the ancestral expression domain (subfunctionalization) or find new functions, which are not necessarily related to the original function (neofunctionalization [95]). This is, however, not true for all genes, and we can conclude that the pathway is not evolving as a unit but each gene follows its own history, as has been shown previously for Bacteria and Archaea [25, 26]. For a better understanding of the gene-duplication history, further genome projects on a greater diversity of evolutionary lineages will be required.

Methods

Sequencing

ENO and FBA cDNAs for bichir Polypterus ornatipinnis, sturgeon Acipenser baerii and caecilian Typhlonectes natans were sequenced using degenerated primers designed based on amino-acid alignments of previously known sequences and the rapid amplification of cDNA end (RACE) method to obtain complete coding sequences. Total RNA was extracted from muscle tissue freshly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Extractions were performed with Trizol (Gibco, Germany). cDNA first strand syntheses were done using the First Strand synthesis kit following the manufacturers manual (Gibco, Germany). A c-tailing step was added to allow 5' RACE. Fragments were amplified using degenerate primers based on the amino-acid sequences of previously reported sequences. See Table 1 for sequences of degenerate primers. Amplification was performed in 50-μl reactions containing 0.5 units of RedTaq (Sigma, Germany), RedTaq reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 1.1 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin), 0.2 μM of each primer (MWG-Biotech AG, Germany, 0.4 mM dNTPs (Peqlab Biotechnology, Germany) and 0.5 mM MgCl2. Cycle conditions included an initial denaturation step of 94°C, then 35 cycles of 94°C for 10 seconds, 42°C for 1 minute and 72°C for 2 minutes. Final extension was performed at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified either directly or, in cases of multiple bands, by cutting bands from 1% agarose gels and using the QIAGEN spin system. 3' RACE reactions were performed with nested approaches of two sequence-specific primers and the Not-I short primer (AAC TGG AAG AAT TCG CGG CC). 5'RACE were preformed with nested sequence specific primers and the oligo-G primer binding the c-tail at the 5' end of the cDNA (CTA GTA CGG GII GGG IIG GG). Sequences were confirmed by amplification and sequencing of both strands of the complete coding sequences by specific primers located in the 5' and 3' non-coding regions. Cycle sequencing was performed using the ABI sequencing mix and 35 cycles of 94°C for 10 seconds, 42°C – 50°C for 10 seconds and 68°C for 4 minutes. Sequences were run on an ABI3100 capillary sequencer. Sequences were proofread and assembled using Sequence Navigator [102].

Database searches and sequence analyses

Protein sequences of pufferfishes (Tetraodon nigroviridis, Takifugu rubripes) zebrafish (Danio rerio), human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus), rat (Rattus norvegicus) chicken (Gallus gallus), claw frogs (Xenopus laevis, Xenopus tropicalis), sturgeon (Acipenser baerii), caecilian (Typhlonectes natans), bichir (Polypterus sp.), lamprey (Lethenteron sp, Eptatretus burgeri), shark (Cephaloscyllium umbratile), and ray (Potamotrygon motoro) were obtained from the Ensembl database [103] or by conducting BLAST (BLASTp and translated BLAST) searches [104] against GenBank. All accession numbers are listed in the supplementary data. Sequences were aligned with Clustal X [105]. For each alignment, a preliminary tree was drawn. This tree facilitated the identification of identical sequences, sequences that varied only in length, and multiple sequences within species that differed by only few amino acids, all of which were removed from the alignment. Draft trees were reconstructed from the remaining sequences using Poisson-corrected genetic distances and the neighbor-joining algorithm [106] in MEGA 3.0 [107]. If subsequent phylogenetic surveys provided an indication for fish-specific gene duplication, additional BLAST searches were conducted to find more putative actinopterygian copies. With a few exceptions, human "reference sequences" [108] were used as query sequences for the BLAST searches. Species were surveyed one at a time to improve the identification of a drop in sequence similarity, which was used as a "cut-off" criterion.

As outgroup sequences, we used data from Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster and Ciona intestinalis. In one case (GAPDH), we used data from Schistosoma mansoni and Crassostrea gigas as outgroup sequences. In another case (PGK), we extended the dataset with protein sequences from Oryzias latipes, Lepisosteus osseus, Rana sylvatica, Equus caballus, Sus scrofa, Bos taurus and Macropus eugenii. Amino-acid data were analyzed using PHYML [109] and the maximum-likelihood (ML) model, and parameters were chosen based on ProtTest [110] analyses. Confidence in estimated relationships of ML tree topologies was evaluated by a bootstrap analysis with 500 replicates [111] and Bayesian methods of phylogeny inference. Bayesian analyses were initiated with random seed trees and were run for 200,000 generations. The Markov chains were sampled at intervals of 100 generations with a burn-in of 1000 trees. Bayesian phylogenetic analyses were conducted with MrBayes 3.1.1 [112].

References

Ohno S: Evolution by Gene Duplication. 1970, New York: Springer-Verlag

Hokamp K, McLysaght A, Wolfe KH: The 2R hypothesis and the human genome sequence. J Struc Funct Genomics. 2003, 3: 95-110. 10.1023/A:1022661917301.

Panopoulou G, Poustka AJ: Timing and mechanism of ancient vertebrate Genome Duplication. The adventure of a hypothesis. Trends Genet. 2005, 21: 559-567. 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.004.

Hughes AL, Robert F: 2R or not 2R: Testing hypotheses of genome duplication in early vertebrates. J Struc Funct Genomics. 2003, 3: 85-93. 10.1023/A:1022681600462.

Hughes AL: Phylogenies of Developmentally Important Proteins Do Not Support the Hypothesis of Two Rounds of Genome Duplication Early in Vertebrate History. J Mol Evol. 1999, 48: 565-576. 10.1007/PL00006499.

Sidow A: Gen(om)e duplications in the evolution of early vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996, 6: 715-722. 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80026-8.

Sharman AC, Holland PWH: Conservation, duplication, and divergence of developmental genes during chordate evolution. Neth J Zool. 1996, 46: 47-67.

Robinson-Rechavi M, Boussau B, Laudet V: Phylogenetic dating and characterization of gene duplications in vertebrates: the cartilaginous fish reference. Mol Biol Evol. 2004, 21: 580-586. 10.1093/molbev/msh046.

Stadler PF, Fried C, Prohaska S, Bailey WJ, Misof BY, Ruddle FH, Wagner GP: Evidence for independent Hox gene duplications in the hagfish lineage: a PCR-based gene inventory of Eptatretus stoutii. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004, 32: 686-694. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.03.015.

Meyer A, Schartl M: Gene and genome duplications in vertebrates: the one-to-four (-to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999, 11: 699-704. 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00039-3.

Taylor JS, Van de Peer Y, Braasch I, Meyer A: Comparative genomics provides evidence for an ancient genome duplication event in fish. Phil Trans R Soc Lond Ser B. 2001, 356: 1661-1679. 10.1098/rstb.2001.0975.

Taylor JS, Braasch I, Frickey T, Meyer A, Van de Peer Y: Genome duplication, a trait shared by 22000 species of ray-finned fish. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 382-390. 10.1101/gr.640303.

Van de Peer Y, Taylor JS, Meyer A: Are all fish ancient polyploids?. J Struc Funct Genomics. 2003, 2: 65-73. 10.1023/A:1022652814749.

Christoffels A, Koh EG, Chia JM, Brenner S, Aparicio S, Venkatesh B: Fugu genome analysis provides evidence for a whole-genome duplication early during the evolution of ray-finned fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2004, 21: 1146-1151. 10.1093/molbev/msh114.

Vandepoele K, De Vos W, Taylor JS, Meyer A, Van de Peer Y: Major events in the genome evolution of vertebrates: Paranome age and size differs considerably between ray-finned fishes and land vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 1638-1643. 10.1073/pnas.0307968100.

Jaillon O, Aury J-M, Brunet F, Petit J-L, Stange-Thomann N, Mauceli E, Bouneau L, Fischer C, Ozouf-Costaz C, Bernot A, Nicaud S, Jaffe D, Fisher S, Lutfalla G, Dossat C, Segurens B, Dasilva C, Salanoubat M, Levy M, Boudet N, Castellano S, Anthouard V, Jubin C, Castelli V, Katinka M, Vacherie B, Biemont C, Skalli Z, Cattolico L, Poulain J, De Berardinis V, Cruaud C, Duprat S, Brottier P, Coutanceau JP, Gouzy J, Parra G, Lardier G, Chapple C, McKernan KJ, McEwan P, Bosak S, Kellis M, Volff JN, Guigo R, Zody MC, Mesirov J, Lindblad-Toh K, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Kahn D, Robinson-Rechavi M, Laudet V, Schachter V, Quetier F, Saurin W, Scarpelli C, Wincker P, Lander ES, Weissenbach J, Roest Crollius H: Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype. Nature. 2004, 431: 946-957. 10.1038/nature03025.

Lynch M, Conery JS: The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000, 290: 1151-1155. 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151.

Postlethwait JH, Woods IG, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan YL, Kelly PD, Chu F, Huang H, Hill-Force A, Talbot WS: Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res. 2000, 10: 1890-1902. 10.1101/gr.164800.

Lynch M, Force A: The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics. 2000, 154: 459-473.

Ohno S: Ancient linkage groups and frozen accidents. Nature. 1973, 244: 259-262. 10.1038/244259a0.

Gibson TJ, Spring J: Evidence in Favour of Ancient Octaploidy in the Vertebrate Genome. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999, 28: 259-264.

Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J: Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999, 151: 1531-1545.

Canback B, Andersson SG, Kurland CG: The global phylogeny of glycolytic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 6097-6102. 10.1073/pnas.082112499.

Oslancová A, Janecek S: Evolutionary relatedness between glycolytic enzymes most frequently occuring in genomes. Folia Microbiol. 2004, 49: 247-258.

Dandekar T, Schuster S, Snel B, Huynen M, Bork P: Pathway alignment: application to the comparative analysis of glycolytic enzymes. Biochem J. 1999, 343: 115-124. 10.1042/0264-6021:3430115.

Cordwell SJ: Microbial genomes and "missing" enzymes: redefining biochemical pathways. Arch Microbiol. 1999, 172: 269-279. 10.1007/s002030050780.

Fothergill-Gilmore LA, Michels PA: Evolution of glycolysis. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1993, 59: 105-235. 10.1016/0079-6107(93)90001-Z.

Erlandsen H, Abola EE, Stevens RC: Combining structural genomics and enzymology: completing the picture in metabolic pathways and enzyme active sites. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000, 10: 719-730. 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00154-8.

Kikugawa K, Katoh K, Kuraku S, Sakurai H, Ishida O, Iwabe N, Miyata T: Basal jawed vertebrate phylogeny inferred from multiple nuclear DNA-coded genes. BMC Biol. 2004, 2: 3-10.1186/1741-7007-2-3.

Hausdorf B: Early evolution of the bilateria. Syst Biol. 2000, 49: 130-142. 10.1080/10635150050207438.

Middleton RJ: Hexokinases and Glucokinases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990, 19: 180-183.

Youn JH, Youn MS, Bergman RN: Synergism of glucose and fructose in net glycogen synthesis in perfused rat livers. J Biol Chem. 1986, 261: 15960-15969.

Spring J: Vertebrate evolution by interspecific hybridisation-are we polyploid?. FEBS Letters. 1997, 400: 2-8. 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01351-8.

Wittbrodt J, Meyer A, Schartl M: More genes in fish?. BioEssays. 1998, 20: 511-515. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199806)20:6<511::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-3.

Bowles J, Schepers G, Koopman P: Phylogeny of the SOX Family of Developmental Transcription Factors Based on Sequence and Structural Indicators. Dev Biol. 2000, 227: 239-255. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9883.

Camacho-Hubner A, Richard C, Beermann F: Genomic structure and evolutionary conservation of the tyrosinase gene family from Fugu. Gene. 2002, 285: 59-68. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00411-0.

Escriva H, Manzon L, Youson J, Laudet V: Analysis of lamprey and hagfish genes reveals a complex history of gene duplications during early vertebrate evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2002, 19: 1440-1450.

Meyer A, Malaga-Trillo E: Vertebrate genomics: More fishy tales about Hox genes. Curr Biol. 1999, 9: R210-213. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80131-6.

Panopoulou G, Hennig S, Groth D, Krause A, Poustka AJ, Herwig R, Vingron M, Lehrach H: New evidence for genome-wide duplications at the origin of vertebrates using an amphioxus gene set and completed animal genomes. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 1056-1066. 10.1101/gr.874803.

Stock DW, Ellies DL, Zhao Z, Ekker M, Ruddle FH, Weiss KM: The evolution of the vertebrate Dlx gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 10858-10863. 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10858.

Taylor JS, Van de Peer Y, Meyer A: Genome duplication, divergent resolution and speciation. Trends Genet. 2001, 17: 299-301. 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02318-6.

Riad-el Sabrouty S, Blanchard JM, Marty L, Jeanteur P, Piechaczyk M: The muridae glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase family. J Mol Evol. 1989, 29: 212-222. 10.1007/BF02100205.

Fothergill-Gilmore LA: Evolution in glycolysis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1987, 15: 993-995.

Hoegg S, Brinkmann H, Taylor JS, Meyer A: Phylogenetic timing of the fish-specific genome duplication correlates with the diversification of teleost fish. J Mol Evol. 2004, 59: 190-203. 10.1007/s00239-004-2613-z.

Crow KD, Stadler PF, Lynch VT, Amemiya C, Wagner GP: The "fish specific" Hox cluster duplication is coincident with the origin of teleosts. Mol Biol Evol. 2006, 23: 121-136. 10.1093/molbev/msj020.

de Souza FSJ, Bumaschny VF, Low MJ, Rubinstein M: Subfunctionalization of expression and peptide domains following the ancient duplication of the Proopiomelanocortin gene in teleost fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2005, 22: 2417-2427. 10.1093/molbev/msi236.

Ludwig A, Belfiore NM, Pitra C, Svirsky V, Jenneckens I: Genome duplication events and functional reduction of ploidy levels in sturgeon (Acipenser, Huso and Scaphirhynchus). Genetics. 2001, 158: 1203-1215.

Fothergill-Gilmore LA, Watson HC: Phosphoglycerate mutases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990, 18: 190-193.

Fares MA, Byrne KP, Wolfe KH: Rate Asymmetry after Genome Duplication Causes Substantial Long-Branch Attraction Artifacts in the Phylogeny of Saccharomyces Species. Mol Biol Evol. 2006, 23: 245-253. 10.1093/molbev/msj027.

Meyer A, Zardoya R: Recent Advances in the (molecular) Phylogeny of Vertebrates. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 2003, 34: 311-338. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132351.

Fothergill-Gilmore LA: The evolution of the glycolytic pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 1986, 11: 47-51. 10.1016/0968-0004(86)90233-1.

Larhammar D, Lundin LG, Hallbook F: The human Hox-bearing chromosome regions did arise by block or chromosome (or even genome) duplications. Genome Res. 2002, 12: 1910-1920. 10.1101/gr.445702.

Lundin LG, Larhammar D, Hallbook F: Numerous groups of chromosomal regional paralogies strongly indicate two genome doublings at the root of the vertebrates. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2003, 3: 53-63. 10.1023/A:1022600813840.

Dehal P, Boore JL: Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3: e314-10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314.

Amores A, Force A, Yan YL, Joly L, Amemiya C, Fritz A, Ho RK, Langeland J, Prince V, Wang YL, Westerfield M, Ekker M, Postlethwait JH: Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genome evolution. Science. 1998, 282: 1711-1714. 10.1126/science.282.5394.1711.

Naruse K, Fukamachi S, Mitani H, Kondo M, Matsuoka T, Kondo S, Hanamura N, Morita Y, Hasegawa K, Nishigaki R, Shimada A, Wada H, Kusakabe T, Suzuki N, Kinoshita M, Kanamori A, Terado T, Kimura H, Nonaka M, Shima A: A Detailed Linkage Map of Medaka, Oryzias latipes: Comparative Genomics and Genome Evolution. Genetics. 2000, 154: 1773-1784.

Amores A, Suzuki T, Yan YL, Pomeroy J, Singer A, Amemiya C, Postlethwait JH: Developmental roles of pufferfish Hox clusters and genome evolution in ray-fin fish. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 1-10. 10.1101/gr.1717804.

Hoegg S, Meyer A: Hox clusters as models for vertebrate genome evolution. Trends Genet. 2005, 21: 421-424. 10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.004.

Deloukas P, Matthews LH, Ashurst J, Burton J, Gilbert JG, Jones M, Stavrides G, Almeida JP, Babbage AK, Bagguley CL, Bailey J, Barlow KF, Bates KN, Beard LM, Beare DM, Beasley OP, Bird CP, Blakey SE, Bridgeman AM, Brown AJ, Buck D, Burrill W, Butler AP, Carder C, Carter NP, Chapman JC, Clamp M, Clark G, Clark LN, Clark SY, Clee CM, Clegg S, Cobley VE, Collier RE, Connor R, Corby NR, Coulson A, Coville GJ, Deadman R, Dhami P, Dunn M, Ellington AG, Frankland JA, Fraser A, French L, Garner P, Grafham DV, Griffiths C, Griffiths MN, Gwilliam R, Hall RE, Hammond S, Harley JL, Heath PD, Ho S, Holden JL, Howden PJ, Huckle E, Hunt AR, Hunt SE, Jekosch K, Johnson CM, Johnson D, Kay MP, Kimberley AM, King A, Knights A, Laird GK, Lawlor S, Lehvaslaiho MH, Leversha M, Lloyd C, Lloyd DM, Lovell JD, Marsh VL, Martin SL, McConnachie LJ, McLay K, McMurray AA, Milne S, Mistry D, Moore MJ, Mullikin JC, Nickerson T, Oliver K, Parker A, Patel R, Pearce TA, Peck AI, Phillimore BJ, Prathalingam SR, Plumb RW, Ramsay H, Rice CM, Ross MT, Scott CE, Sehra HK, Shownkeen R, Sims S, Skuce CD, Smith ML, Soderlund C, Steward CA, Sulston JE, Swann M, Sycamore N, Taylor R, Tee L, Thomas DW, Thorpe A, Tracey A, Tromans AC, Vaudin M, Wall M, Wallis JM, Whitehead SL, Whittaker P, Willey DL, Williams L, Williams SA, Wilming L, Wray PW, Hubbard T, Durbin RM, Bentley DR, Beck S, Rogers J: The DNA sequence and comparative analysis of human chromosome 20. Nature. 2001, 414: 865-871. 10.1038/414865a.

Ramsden SD, Brinkmann H, Hawryshyn CW, Taylor JS: Mitogenomics and the sister of Salmonidae. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003, 18: 607-610. 10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.020.

Meyer A, Van de Peer Y: From 2R to 3R: evidence for the fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD). Bio Essays. 2005, 27: 1-9.

Van de Peer Y, Frickey T, Taylor J, Meyer A: Dealing with saturation at the amino acid level: a case study based on anciently duplicated zebrafish genes. Gene. 2002, 295: 205-211. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00689-3.

Horton AC, Mahadevan NR, Ruvinsky AO, Gibson-Brown JJ: Phylogenetic analyses alone are insufficient to determine whether genome duplication(s) occurred during early vertebrate evolution. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2003, 299: 41-53. 10.1002/jez.b.40.

Cardenas ML, Cornish-Bowden A, Ureta T: Evolution and regulatory role of the hexokinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998, 1401: 242-264. 10.1016/S0167-4889(97)00150-X.

Niemeyer H, de la Luz Cardenas M, Rabajille E, Ureta T, Clark-Turri L, Penaranda J: Sigmoidal kinetics of glucokinase. Enzyme. 1975, 20: 321-333.

Storer AC, Cornish-Bowden A: Kinetics of rat liver glucokinase. Co-operative interactions with glucose at physiologically significant concentrations. Biochem J. 1976, 159: 7-14.

Ureta T, Radojkovic J, Lagos R, Guixe V, Nunez L: Phylogenetic and ontogenetic studies of glucose phosphorylating isozymes of vertebrates. Arch Biol Med Exp (Santiago). 1979, 12: 587-604.

Jeffery CJ, Bahnson BJ, Chien W, Ringe D, Petsko GA: Crystal structure of rabbit phosphoglucose isomerase, a glycolytic enzyme that moonlights as neuroleukin, autocrine motility factor, and differentiation mediator. Biochemistry. 2000, 39: 955-964. 10.1021/bi991604m.

Kao H-w, Lee S-C: Phosphoglucose Isomerases of Hagfish, Zebrafish, Gray Mullet, Toad, and Snake, with Referenco to the Evolution of the Genes in Vertebrates. Mol Biol Evol. 2002, 19: 367-374.

Sun YJ, Chou CC, Chen WS, Wu RT, Meng M, Hsiao CD: The crystal structure of a multifunctional protein: phosphoglucose isomerase/autocrine motility factor/neuroleukin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 5412-5417. 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5412.

Chou CC, Sun YJ, Meng M, Hsiao CD: The crystal structure of phosphoglucose isomerase/autocrine motility factor/neuroleukin complexed with its carbohydrate phosphate inhibitors suggests its substrate/receptor recognition. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 23154-23160. 10.1074/jbc.M002017200.

Dunaway GA: A review of animal phosphofructokinase isozymes with an emphasis on their physiological role. Mol Cell Biochem. 1983, 52: 75-91. 10.1007/BF00230589.

Sols A: Multimodulation of enzyme activity. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1981, 19: 77-101.

Aragon JJ, Sols A: Regulation of enzyme activity in the cell: effect of enzyme concentration. Faseb J. 1991, 5: 2945-2950.

Fernandez de Mattos S, de los Pinos EE, Joaquin M, Tauler A: Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is required for transcriptional activity of F-type 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase: assessment of the role of protein kinase B and p70 S6 kinase. Biochem J. 2000, 349: 59-65. 10.1042/0264-6021:3490059.

Meurice G, Deborde C, Jacob D, Falentin H, Boyaval P, Dimova D: In silico exploration of the fructose-6-phosphate phosphorylation step in glycolysis: genomic evidence of the coexistence of an atypical ATP-dependent along with a PPi-dependent phosphofructokinase in Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii. In Silico Biol. 2004, 4: 517-528.

Kulkarni G, Rao GS, Srinivasan NG, Hofer HW, Yuan PM, Harris BG: Ascaris suum phosphofructokinase. Phosphorylation by protein kinase and sequence of the phosphopeptide. J Biol Chem. 1987, 262: 32-34.

Huse K, Jergil B, Schwidop WD, Kopperschlager G: Evidence for phosphorylation of yeast phosphofructokinase. FEBS Lett. 1988, 234: 185-188. 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81330-9.

Wang W, Gu X: Evolutionary patterns of gene families generated in the early stage of vertebrates. J Mol Evol. 2000, 51: 88-96.

Gamblin SJ, Davies GJ, Grimes JM, Jackson RM, Littlechild JA, Watson HC: Activity and specificity of human aldolases. J Mol Biol. 1991, 219: 573-576. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90650-U.

Schapira F: Isozymes and differentiation. Biomedicine. 1978, 28: 1-5.

Straus D, Gilbert W: Genetic engineering in the Precambrian: structure of the chicken triosephosphate isomerase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1985, 5: 3497-3506.

Merritt TJS, Quattro JM: Evidence for a period of directional selection following gene duplication in a neurally expresed locus of triosephosphate isomerase. Genetics. 2001, 159: 689-697.

Piechaczyk M, Blanchard JM, Riaad-El Sabouty S, Dani C, Marty L, Jeanteur P: Unusual abundance of vertebrate 3-phosphate dehydrogenase pseudogenes. Nature. 1984, 312: 469-471. 10.1038/312469a0.

Hanauer A, Mandel JL: The glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase gene family: structure of a human cDNA and of an X chromosome linked pseudogene; amazing complexity of the gene family in mouse. Embo J. 1984, 3: 2627-2633.

Tso JY, Sun XH, Kao TH, Reece KS, Wu R: Isolation and characterization of rat and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNAs: genomic complexity and molecular evolution of the gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985, 13: 2485-2502.

Fort P, Marty L, Piechaczyk M, el Sabrouty S, Dani C, Jeanteur P, Blanchard JM: Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985, 13: 1431-1442.

Huitorel P, Pantaloni D: Bundling of microtubules by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and its modulation by ATP. Eur J Biochem. 1985, 150: 265-269. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09016.x.

Boer PH, Adra CN, Lau YF, McBurney MW: The testis-specific phosphoglycerate kinase gene pgk-2 is a recruited retroposon. Mol Cell Biol. 1987, 7: 3107-3112.

McCarrey JR, Kumari M, Aivaliotis MJ, Wang Z, Zhang P, Marshall F, Vandeberg JL: Analysis of the cDNA and encoded protein of the human testis-specific PGK-2 gene. Dev Genet. 1996, 19: 321-332. 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)19:4<321::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-B.

McCarrey JR, Thomas K: Human testis-specific PGK gene lacks introns and possesses characteristics of a processed gene. Nature. 1987, 326: 501-505. 10.1038/326501a0.

Pons G, Bartrons R, Carreras J: Hybrid forms of phosphoglycerate mutase and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate synthase-phosphatase. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1985, 129: 658-663. 10.1016/0006-291X(85)91942-4.

Betran E, Wang W, Jin L, Long M: Evolution of the phosphoglycerate mutase processed gene in human and chimpanzee revealing the origin of a new primate gene. Mol Biol Evol. 2002, 19: 654-663.

Rose ZB: The enzymology of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1980, 51: 211-253.

Wistow GJ, Lietman T, Williams LA, Stapel SO, de Jong WW, Horwitz J, Piatigorsky J: Tau-crystallin/alpha-enolase: one gene encodes both an enzyme and a lens structural protein. J Cell Biol. 1988, 107: 2729-2736. 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2729.

Wistow G: Lens crystallins: gene recruitment and evolutionary dynamism. TIBS. 1993, 18: 301-307.

Piatigorsky J: Crystallin genes: specialization by changes in gene regulation my precede gene duplication. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2003, 3: 131-137. 10.1023/A:1022626304097.

McAlister L, Holland MJ: Targeted deletion of a yeast enolase structural gene. Identification and isolation of yeast enolase isozymes. J Biol Chem. 1982, 257: 7181-7188.

Beutler E, Baronciani L: Mutations in pyruvate kinase. Human Mutation. 1996, 7: 1-6. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)7:1<1::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-H.

Ashizawa K, Willingham MC, Liang CM, Cheng SY: In vivo regulation of monomer-tetramer conversion of pyruvate kinase subtype M2 by glucose is mediated via fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1991, 266: 16842-16846.

Parkison C, Ashizawa K, McPhie P, Lin KH, Cheng SY: The monomer of pyruvate kinase, subtype M1, is both a kinase and a cytosolic thyroid hormone binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991, 179: 668-674. 10.1016/0006-291X(91)91424-B.

Parker SR: Sequence Navigator. Multiple sequence alignment software. Methods Mol Biol. 1997, 70: 145-154.

Hubbard T, Andrews D, Caccamo M, Cameron G, Chen Y, Clamp M, Clarke L, Coates G, Cox T, Cunningham F, Curwen V, Cutts T, Down T, Durbin R, Fernandez-Suarez XM, Gilbert J, Hammond M, Herrero J, Hotz H, Howe K, Iyer V, Jekosch K, Kahari A, Kasprzyk A, Keefe D, Keenan S, Kokocinsci F, London D, Longden I, McVicker G, Melsopp C, Meidl P, Potter S, Proctor G, Rae M, Rios D, Schuster M, Searle S, Severin J, Slater G, Smedley D, Smith J, Spooner W, Stabenau A, Stalker J, Storey R, Trevanion S, Ureta-Vidal A, Vogel J, White S, Woodwark C, Birney E.: Ensembl 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33: D447-453. 10.1093/nar/gki138.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410. 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG: The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 4876-4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876.

Saitou N, Nei M: The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987, 4: 406-425.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M: MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004, 5: 150-163. 10.1093/bib/5.2.150.

Maglott DR, Katz KS, Sicotte H, Pruitt KD: NCBI's LocusLink and RefSeq. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28: 126-128. 10.1093/nar/28.1.126.

Guindon S, Gascuel O: A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003, 52: 696-704. 10.1080/10635150390235520.

Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D: ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 2104-2105. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263.

Felsenstein J: Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution Int J Org Evolution. 1985, 39: 783-791.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F: MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001, 17: 754-755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754.

Acknowledgements

We thank Birte Kalveram for technical assistance. Support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to AM and from the Landesgraduiertenförderung Baden-Württemberg to SH is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also would like to thank Ingo Braasch and three anonymous referees for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DS designed the study, carried out the phylogenetic analyses, and drafted the manuscript. SH conceived the study, carried out the molecular work, participated in the phylogenetic analyses and drafted the manuscript. HB participated in the phylogenetic analyses, and helped to draft the manuscript. AM participated in the study design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Dirk Steinke, Simone Hoegg contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12915_2006_71_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional File 1: A complete list of GenBank, JGI, and Ensembl accession numbers of the amino acid sequences used for the phylogenetic analyses of this study is provided in the file (PDF 170 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Steinke, D., Hoegg, S., Brinkmann, H. et al. Three rounds (1R/2R/3R) of genome duplications and the evolution of the glycolytic pathway in vertebrates . BMC Biol 4, 16 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-4-16

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-4-16