Abstract

Background

Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) is an established tool to evaluate for changes associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but has not been studied in sub-clinical IBD. We sought to evaluate the use of MRE in children with spondyloarthritis (SpA), who are at risk of having sub-clinical gut inflammation.

Methods

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) with evidence of intestinal inflammation as evidence by an abnormal fecal calprotectin assay were offered MRE of their intestines. Flavored sports drink containing polyethylene glycol 3350 was used as oral contrast. Glucagon was used to arrest peristalsis. Patients were imaged in the prone position on a 1.5 T scanner. Heavily T2-weighted fat-suppressed coronal and axial images using breath-hold technique were obtained, followed by post-gadolinium fat-suppressed T1-weighted gradient echo images.

Results

We recruited five children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA); four had SpA, and one had poly-articular JIA. All five had evidence of intestinal inflammation based upon a positive fecal calprotectin assay and successfully completed the MRE. Three of the studies showed findings suggestive of IBD, including thickening and contrast uptake at the terminal ileum (TI) in one child, contrast uptake of the distal ileum in another, and prominent vasa recta and mesenteric lymph nodes in the third. The child with evidence of inflammatory changes at the TI underwent colonoscopy, which revealed inflammatory bowel disease limited to the TI.

Conclusions

MRE can be used to evaluate for subclinical IBD in children with JIA. This protocol was safe and well-tolerated, and identified mild changes in three of the subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately two-thirds of adults with spondyloarthritis (SpA) have inflammatory intestinal changes similar to those detected in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [1]. Similar findings were reported in a small pediatric study [2]. However, these studies used colonoscopy, an expensive and invasive tool and thus one that is not well suited for research studies. Studies using barium swallow and sigmoidoscopy have identified sub-clinical intestinal inflammation in lower percentages of SpA patients, suggesting decreased sensitivity in that population [3, 4]. Computed tomography involves significant amounts of radiation exposure, and ultrasound is limited in some centers by operator-dependence [5]. However, one potential tool that could be used safely to evaluate the intestines in children and adults with SpA is magnetic resonance enterography (MRE).

MRE is an accepted tool to diagnose and monitor IBD. Although it does not visualize early mucosal changes such as aphthous ulcerations, MRE allows for the detection of bowel wall thickening and enhancement, as well as extramural complications of IBD, including strictures, fistulas, sinus tracts, abscesses, fibro-fatty proliferation, and lymphadenopathy [5–10]. Studies in adults and children have shown MRE to be accurate in the diagnosis of IBD, distinguishing it from other causes of abdominal pain with sensitivity 82 - 96% and specificity > 90% [11–15].

These studies raise the possibility that MRE may be of benefit to screen for subclinical intestinal inflammation in SpA patients. We previously recruited children with enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) and other subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), and obtained measurements of fecal calprotectin, a stool study that assesses the presence of inflammation based on neutrophil-derived proteins that are resistant to metabolic breakdown by intestinal bacteria and can assist in differentiating inflammatory from non- inflammatory states [16]. In that study, we showed elevated fecal calprotectin levels in ERA patients, as compared to children with other JIA subtypes, as well as controls consisting of children with unrelated connective tissue diseases and non-inflammatory causes of joint pain [17]. A limitation of fecal calprotectin is that it does not provide any information as to the location of the inflammation or the presence of specific complications potentially associated with IBD. Thus, to evaluate the anatomic location and extent of sub-clinical intestinal inflammation in children potentially at higher risk of intestinal inflammation, we performed a sub-study of the above, offering MRE to JIA patients with elevated fecal calprotectin levels.

Methods

Patients

This was a prospective sub-study of fecal calprotectin levels among patients with JIA [17], diagnosed according to the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) criteria [18]. Calprotectin levels were measured via ELISA in a commercial laboratory (ARUP, Salt Lake City, UT), with values < 50 micrograms/gm considered negative, 50 - 120 borderline, and ≥ 121 elevated. Inclusion criteria for the current study were a fecal calprotectin level of at least 121 micrograms/gm obtained as part of that study. Exclusion criteria were inability to cooperate with the procedure, allergy to IV contrast, renal insufficiency, MRI incompatible devices or implants, and pregnancy; in practice, the only exclusion criteria applied was inability to undergo MRI without sedation. There was no strict age cut-off, although most children under age 8 or 9 would not be expected to be able to undergo unsedated MRI. All of the JIA patients with elevated fecal calprotectin levels (≥ 121 micrograms/gm) who were potentially mature enough to undergo MRI without sedation were invited to do so; of the 8 who met the inclusion criteria, 5 agreed to participate. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the UT Southwestern Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from each subject's legal guardian, and assent was obtained from each child.

MR enterography

Preparation

Patients were NPO for six hours prior to the study. We used one packet (17 gm) of polyethylene glycol 3350 (over the counter Miralax®) dissolved in a flavored commercial sports beverage (Gatorade®) in order to increase bowel wall distension. Over the course of 2.5 hours, they were given a total volume of 1250 ml; one quarter of the total volume was taken approximately every 30 minutes, with the final dose given 15 - 30 minutes prior to the study. To inhibit bowel peristalsis, patients were administered 0.5 mg glucagon IV at the onset of the study; a second dose was given if the radiologist (MDR) determined that there was motion artifact suggestive of peristalsis.

MR examination

Patients were imaged in the prone position. Utilizing a body surface coil an MRI exam was acquired on a GE 1.5 Tesla (Milwaukee, WI) MR scanner. To minimize motion artifact, the patient was asked to hold his or her breath during image acquisition, and as stated above, bowel motion was reduced with the administration of glucagon. Sequences and parameters are summarized in Table 1. The precontrast images allowed visualization of bowel wall thickening, mesenteric lymph nodes, and prominent vasa recta. IV gadolinium, 0.1 mmole/kg (max 10 mmole) of gadoteridol (Prohance; Bracco diagnostics) was then administered, and additional images were acquired for the detection of bowel enhancement suggesting active inflammation.

Results and discussion

Patient population

Nine subjects with JIA had elevated fecal calprotectin levels. One was incapable of undergoing unsedated MRI, and three declined to participate in the MRI study. Thus, five patients agreed to participate, and all five completed the study (Table 2). There were no obvious differences between active joint count, disease duration, or presence vs absence of gastroenterology symptoms between the five who participated and the three who did not (data not shown.) All five had JIA and had an elevated fecal calprotectin level (median 249). Four had ERA; one had poly-articular JIA. Only one (patient # 4) had significant gastrointestinal symptoms, consisting of abdominal pain and weight loss prior to treatment with corticosteroids, although he was asymptomatic at the time of the study.

MR enterography findings

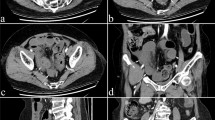

Patients # 2 and 3 had normal studies (Figure 1.) Patient 1 revealed increased bowel wall thickness (4 mm; Figure 2A) and enhancement (2B) at the terminal ileum (TI). Patient 4 showed multiple mesenteric lymph nodes and prominent vasa recta (Figure 3.) Patient 5 showed increased contrast uptake at the distal ileum, without thickening (Figure 4.) There was no obvious correlation between the presence or type of bowel wall inflammation and the fecal calprotectin levels.

Normal bowel. Axial T1 fSPGR with fat saturation post contrast at the area of the distal ileum in 16 yo male with ERA (patient 2); no bowel thickening or contrast uptake is evident a. Coronal 2D FIESTA (pre-contrast image) in 11 yo female with poly-articular JIA, with a normal TI indicated by the arrow (patient 3) b.

Safety

The study was tolerated without any serious adverse events. Patient 1 had mild emesis after the second dose of glucagon. No other adverse events were reported.

Patient follow-up

The patients were followed for a median of 9.6 months (range 5.3 - 15) after the MRI. Patient 1 subsequently developed abdominal pain and was therefore referred to gastroenterology; 5 weeks after the MRE, he underwent colonoscopy, which revealed non-specific inflammatory changes limited to the TI, prompting a diagnosis of IBD. His medical management was changed from etanercept to adalimumab, in order to treat his underlying bowel disease; he subsequently has had improvement in arthritis, albeit still active at the final visit. Patient # 4 was referred to gastroenterology but never made the appointment. Nevertheless, due to the presence of active arthritis as well as acute anterior uveitis, he was also started on adalimumab, with improvement in his arthritis symptoms, but continued to have active arthritis at the end of the follow-up period. None of the other patients underwent changes in their medical management and were doing well at the final follow-up. Patients 2, 3, and 5 were not diagnosed with IBD or other intestinal illnesses.

The primary implication of this study is in demonstrating that MRE may be a tool with which investigators can evaluate for subtle inflammatory changes in patients with SpA. The gold standard, ileocolonoscopy, is invasive and expensive, and thus not well-suited for research purposes. Fecal calprotectin levels are elevated in children with SpA [17], but they do not provide specific anatomical information within the intestines, and it appears that their levels can be increased nearly two-fold by use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [19, 20]. Likewise, wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) can identify subclinical changes in SpA patients [21]; however, WCE does not identify changes beyond the intestinal mucosa, and is limited by risk of obstruction.

This study also provides further exploration of the connection between intestinal inflammation and SpA. We have previously hypothesized that in children with SpA, intestinal inflammation helps maintain peripheral synovitis via mechanisms yet unclear [22]. However, the extent of inflammation need not be extensive; indeed, while the majority of patients with SpA have intestinal inflammation [1], only a minority develop frank IBD. Likewise, in our study, the MRI findings were subtle, and none showed the extensive complications previously reported in IBD patients [9, 10], and thus none of the patients were diagnosed with IBD on the basis of the MRI. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors differ in their capacity to treat established IBD, with etanercept less efficacious as compared to some of the TNF monoclonal antagonists [23, 24]. It follows that they may also differ in their capacity to treat sub-clinical intestinal inflammation, such as that identified in this study. If it is indeed the case that sub-clinical intestinal inflammation helps maintain peripheral arthritis in SpA, long-lasting remission may not be possible in the absence of control of this intestinal inflammation. Indeed, registry data indicates that successful withdrawal of etanercept in children with ERA is rare [25].

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small, there was no control population, and there was no gold standard study performed. Nevertheless, we believe that these findings are specific and meaningful; two of the patients had changes in the distal ileum, a common site of inflammation in IBD [26], and in one, colonoscopy confirmed inflammation at that location.

Conclusions

Magnetic resonance enterography identified subclinical intestinal inflammation in three children with spondyloarthritis. Future studies should prospectively screen newly-diagnosed children with ERA for intestinal inflammation with tools such as fecal calprotectin or MRE and evaluate whether or not the presence of such inflammation predicts response to anti-TNF therapy or ability to be withdrawn successfully from such therapy.

Abbreviations

- ERA:

-

enthesitis-related arthritis

- FIESTA:

-

fast imaging employing steady state acquisition

- fSPRG:

-

fast spoiled gradient recalled echo

- IBD:

-

inflammatory bowel disease

- JIA:

-

juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- LAVA:

-

liver acquisition with volume acceleration

- MRE:

-

magnetic resonance enterography

- SpA:

-

spondyloarthritis

- TI:

-

terminal ileum.

References

Mielants H, Veys EM, Goemaere S, Goethals K, Cuvelier C, De Vos M: Gut inflammation in the spondyloarthropathies: clinical, radiologic, biologic and genetic features in relation to the type of histology. A prospective study. J Rheumatol. 1991, 18 (10): 1542-51.

Mielants H, Veys EM, Cuvelier C, De Vos M, Goemaere S, Maertens M, Joos R: Gut inflammation in children with late onset pauciarticular juvenile chronic arthritis and evolution to adult spondyloarthropathy--a prospective study. J Rheumatol. 1993, 20 (9): 1567-72.

McBride JA, King MJ, Baikie AG, Crean GP, Sircus W: Ankylosing Spondylitis and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases of the Intestines. Br Med J. 1963, 2 (5355): 483-6. 10.1136/bmj.2.5355.483.

Costello PB, Alea JA, Kennedy AC, McCluskey RT, Green FA: Prevalence of occult inflammatory bowel disease in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1980, 39 (5): 453-6. 10.1136/ard.39.5.453.

Tolan DJ, Greenhalgh R, Zealley IA, Halligan S, Taylor SA: MR enterographic manifestations of small bowel Crohn disease. Radiographics. 2010, 30 (2): 367-84. 10.1148/rg.302095028.

Bernstein CN, Greenberg H, Boult I, Chubey S, Leblanc C, Ryner L: A prospective comparison study of MRI versus small bowel follow-through in recurrent Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005, 100 (11): 2493-502. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00239.x.

Mann EH: Inflammatory bowel disease: imaging of the pediatric patient. Semin Roentgenol. 2008, 43 (1): 29-38. 10.1053/j.ro.2007.08.005.

Lin MF, Narra V: Developing role of magnetic resonance imaging in Crohn's disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008, 24 (2): 135-40. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f49b14.

Frokjaer JB, Larsen E, Steffensen E, Nielsen AH, Drewes AM: Magnetic resonance imaging of the small bowel in Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005, 40 (7): 832-42. 10.1080/00365520510015683.

Torkzad MR, Ullberg U, Nystrom N, Blomqvist L, Hellstrom P, Fagerberg UL: Manifestations of small bowel disease in pediatric Crohn's disease on magnetic resonance enterography. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011

Laghi A, Borrelli O, Paolantonio P, Dito L, Buena de Mesquita M, Falconieri P, Cucchiara S: Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the terminal ileum in children with Crohn's disease. Gut. 2003, 52 (3): 393-7. 10.1136/gut.52.3.393.

Darbari A, Sena L, Argani P, Oliva-Hemker JM, Thompson R, Cuffari C: Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: a useful radiological tool in diagnosing pediatric IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004, 10 (2): 67-72. 10.1097/00054725-200403000-00001.

Borthne AS, Abdelnoor M, Rugtveit J, Perminow G, Reiseter T, Klow NE: Bowel magnetic resonance imaging of pediatric patients with oral mannitol MRI compared to endoscopy and intestinal ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2006, 16 (1): 207-14. 10.1007/s00330-005-2793-y.

Magnano G, Granata C, Barabino A, Magnaguagno F, Rossi U, Calevo MG, Toma P: Polyethylene glycol and contrast-enhanced MRI of Crohn's disease in children: preliminary experience. Pediatr Radiol. 2003, 33 (6): 385-91.

Horsthuis K, Bipat S, Bennink RJ, Stoker J: Inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed with US, MR, scintigraphy, and CT: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Radiology. 2008, 247 (1): 64-79. 10.1148/radiol.2471070611.

Tibble J, Teahon K, Thjodleifsson B, Roseth A, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, Foster R, Sherwood R, Fagerhol M, Bjarnason I: A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2000, 47 (4): 506-13. 10.1136/gut.47.4.506.

Stoll ML, Punaro M, Patel AS: Fecal Calprotectin in Children with the Enthesitis-related Arthritis Subtype of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011, 38 (10): 2274-5. 10.3899/jrheum.110508.

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J: International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004, 31 (2): 390-2.

Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Scott D, Fagerhol MK, Roseth A, Bjarnason I: High prevalence of NSAID enteropathy as shown by a simple faecal test. Gut. 1999, 45 (3): 362-6. 10.1136/gut.45.3.362.

Meling TR, Aabakken L, Roseth A, Osnes M: Faecal calprotectin shedding after short-term treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996, 31 (4): 339-44. 10.3109/00365529609006407.

Eliakim R, Karban A, Markovits D, Bardan E, Bar-Meir S, Abramowich D, Scapa E: Comparison of capsule endoscopy with ileocolonoscopy for detecting small-bowel lesions in patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Endoscopy. 2005, 37 (12): 1165-9. 10.1055/s-2005-870559.

Stoll ML: Interactions of the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system in the pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29 (2): 322-30.

Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, O'Connor P, Emery P: Efficacy of etanercept for treatment of Crohn's related spondyloarthritis but not colitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003, 62 (1): 74-6. 10.1136/ard.62.1.74.

Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P: Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011, 106 (4): 644-59. 10.1038/ajg.2011.73. quiz 660

Otten MH, Prince FH, Twilt M, Ten Cate R, Armbrust W, Hoppenreijs EP, Koopman-Keemink Y, Wulffraat NM, Gorter SL, Dolman KM, Swart JF, van den Berg JM, van Rossum MA, van Suijlekom-Smit LW: Tumor necrosis factor-blocking agents for children with enthesitis-related arthritis--data from the dutch arthritis and biologicals in children register, 1999-2010. J Rheumatol. 2011, 38 (10): 2258-63. 10.3899/jrheum.110145.

Caprilli R: Why does Crohn's disease usually occur in terminal ileum?. J Crohns Colitis. 2008, 2 (4): 352-6. 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.06.001.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Stoll was supported by Grant Number UL1RR024982, titled, "North and Central Texas Clinical and Translational Science Initiative" (Milton Packer, M.D., PI) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MS - study design, patient recruitment, manuscript preparation; AP - data analysis, manuscript review; MP - study design; MDR - study design, interpretation of MR images, manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Stoll, M.L., Patel, A.S., Punaro, M. et al. MR enterography to evaluate sub-clinical intestinal inflammation in children with spondyloarthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol 10, 6 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-10-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-10-6