Abstract

The field of cellular therapy of cancer is moving quickly and the issues involved with its advancement are complex and wide ranging. The growing clinical applications and success of adoptive cellular therapy of cancer has been due to the rapid evolution of immunology, cancer biology, gene therapy and stem cell biology and the translation of advances in these fields from the research laboratory to the clinic. The continued development of this field is dependent on the exchange of ideas across these diverse disciplines, the testing of new ideas in the research laboratory and in animal models, the development of new cellular therapies and GMP methods to produce these therapies, and the testing of new adoptive cell therapies in clinical trials. The Summit on Cell Therapy for Cancer to held on November 1 and 2, 2011 at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) campus will include a mix of perspectives, concepts and ideas related to adoptive cellular therapy that are not normally presented together at any single meeting. This novel assembly will generate new ideas and new collaborations and possibly increase the rate of advancement of this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

On November 1 and 2, 2011 at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) campus in Bethesda, Maryland a multidisciplinary summit of laboratory and clinical investigators and individuals involved in the clinical use, manufacture, evaluation and regulation of cellular therapies for the treatment of cancer will meet to discuss the most recent advances and promising cellular therapies of cancer (http://www.sitcancer.org/meetings/am11/summit11). The meeting is sponsored by the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC). The purpose of this Summit is to bring clinical and laboratory investigators and those involved with producing, assessing and regulating cellular therapies, together to present and discuss important scientific and technical advances that currently or will soon impact the field.

The Summit is important because this field is moving quickly and the issues involved with its advancement are complex and wide ranging. Regular, more focused immune therapy of cancer meetings remain important and, in fact, are critical to the advancement of adoptive cellular therapy of cancer, but this and most other areas of clinical therapy will benefit from the cross-fertilization that results from the interactions with other related clinical fields, regulatory agencies and industry.

While immunology, cell biology and cancer biology have been the cornerstones of adoptive cellular therapy, gene transfer, cell reprogramming and stem cell biology are emerging as important contributors to this field. All of these areas will be discussed at the Summit on Cell Therapy for Cancer. The meeting will include lectures on adoptive cellular therapy using tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, reprogramming immune and stem cells, new methods for cell expansion, regulatory considerations and bringing new technologies from the research laboratory to the clinic.

The clinical promise of cellular therapies is growing rapidly. The treatment of metastatic melanoma with TIL, which was pioneered by the Surgery Branch, NCI, NIH, is becoming more effective and its use is becoming more widespread. Since TIL were first used to successfully treat melanoma is 1988 [1], several improvements have been made. Preconditioning patients with lymphocyte depleting chemotherapy increased the proportion of patients with objective clinical responses to 50% [2]. Further intensification of the lymphocyte depleting preconditioning using cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and total body irradiation (TBI) along with marrow rescue by the administration of autologous CD34+ isolated from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood stem cell products improved objective clinical response rates to 72% [3, 4]. Several institutions are now using TIL to treat melanoma [4–7]. Other groups have used expanded antigen specific CD8+ T cells for adoptive cellular therapy of melanoma [8–11]. Some investigators are using autologous dendritic cells or artificial antigen presenting cells pulsed with tumor antigens to expand cytotoxic T cells for melanoma therapy [8, 9].

Immune therapy of cancer has spread well beyond the treatment of melanoma. The field of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is moving from a cell replacement therapy to an adoptive cellular therapy. In fact, in many respects the fields of immune therapy of cancer and HSCT are merging. The non-myleoablative chemotherapy and TBI regimen and autologous CD34+ cell rescue used as part of adoptive cellular therapy protocols used to treat metastatic melanoma are similar to those used for HSCT. For many years lymphocytes collected from HSCT donors have been infused following HSCT as an adoptive cellular therapy to treat leukemia relapse following transplantation; particularly chronic myelogenous leukemia [12]. Lymphocytes from the HSCT donor are also being used to treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) associated B cell lymphoproliferative disease in HSCT recipients. These post-transplant lymphoproliferative diseases (PTLDs) occur most often in recipients of T cell depleted grafts. PTLD can be treated with the infusion of unmanipulated donor lymphocytes, but this is associated with a high risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). In order to avoid GVHD, PTLDs are being treated with donor derived EBV-specific T cells [13, 14]. These EBV-specific T cells are generated by culturing donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid B cell lines (LCL) which effectively express EBV antigens and function as antigen presenting cells. Treatment of PTDL with EBV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) is effective in more than 80% of patients, and when used prophylaxtically in high risk patients is effective at preventing PTDL [15].

A number of groups are investigating the use of T cells specific to the leukemia antigens such as Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) [16, 17] and proteinase 3 (PR3) [18] to prevent or treat leukemia relapse following HSCT. In addition, recently, vaccination has been able to induce robust T cell responses against cancer-associated antigens such as viral oncogenic proteins [19]. This offers the prospect to combine proper vaccine strategies with adoptive transfer of specific T cells to achieve optimal T cell expansion and therapeutic benefit [20].

Adoptive cellular therapy protocols have also begun to use NK cells. Clinical investigators interested in treating both cancer and hematologic malignancies and leukemia have been using both allogeneic and autologous natural killer (NK) cells as adoptive cellular therapy. To treat disease relapse in HSCT recipients with hematologic malignancies NK cells from the HSCT donors are being administering post-transplant. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from the HLA-matched donors are enriched for NK cells by the depletion of CD3+ T cells using anti-CD3 immunomagentic beads or by CD3+ T cell depletion followed by CD56+ cell selection [21]. The allogeneic NK cells are administered to the recipient at the time of disease relapse. The NK cell recipient is immunosuppressed and treated with IL-2 to allow for in vivo NK cell expansion. This NK cell therapy has resulted in complete hematological remission in 5 of 19 patients treated with acute myelogenous leukemia [22]. Similar NK cell preparations and treatment protocols have been used to treat patients with recurrent breast cancer and ovarian cancer [23] and refractory lymphoma [24]. The patients were given a lymphodepleting preparative regimen and were then treated with NK cells from HLA haplotype identical donors followed by 6 doses of IL-2 therapy. Among the 6 patients with refractory lymphoma, 4 have had objective clinical responses [24].

Other investigators are using ex vivo expanded autologous NK cells as primary therapy for cancer [25]. Autologous NK cells were isolated using a two step process from PBMC products collected from the patient by apheresis. PBMCs in the apheresis product are depleted of T cell using anti-CD3 immunomagentic beads and then NK cells are selected using anti-CD56 immunomagentic beads. The isolated NK cells are then expanded by incubation with lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) as feeder cells and IL-2. The autologous expanded NK cells are being used to treat patients with advanced malignancies [26].

Gene therapy is becoming an important part of cellular therapy for cancer and hematologic malignancies, particularly, dendritic cell (DC) therapy. DCs have been used in many clinical trials of immunotherapy for cancer. For these studies DCs are usually generated by incubating peripheral blood monocytes with the differentiating agents IL-4 and GM-CSF to produce immature DCs (iDCs) which are used for some clinical trials, but for most trials iDCs are incubated with maturation agents to produce mature DCs (mDCs) [27]. Typically, DCs are loaded with immune dominant peptides or proteins prior to their administration [8, 9], however, many clinical trials are now using genetically engineered DCs to epitope-load HLA antigens [17]. For many years adoptive cellular therapy using genetically engineered cells has been used to treat Hodgkin's lymphoma. The same EBV-specific CTLs that have used to treat PTLD have also been used to treat EBV-positive Hodgkin's Disease (EBV-HD) [14]. While some patients responded to this therapy, the frequency of T cell clones recognizing the EBV antigen expressed in Hodgkin's disease, LMP2, is low. As a result LMP2 specific CTLs were generated by first culturing T cells with DCs transduced with recombinant adenovirus encoding LMP2A followed by expansion by culture with LCL transduced with the same vector [14]. The treatment of 6 patients with high risk EBV-associated lymphomas in relapse with these LMP2 specific CTLs resulted in clinical responses in 5 patients [28].

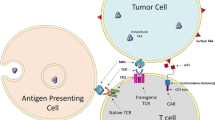

Another very promising use of genetically engineered cells for the treatment of cancer involves arming autologous T cells with T cell receptors (TCR) that have a high affinity to cancer antigens, expanding these genetically modified T cells in vitro and infusing them into patients [29]. T cells transduced with a high affinity TCRs for the melanoma antigens MART-1 and gp100 are being used to treat patients with metastatic melanoma [30, 31]. Clinical responses were seen in 19% and 30% of patients [30, 31]. In addition, high affinity TCRs specific for NY-ESO-1, a cancer antigen expressed by approximately 80% of patients with synovial cell sarcoma and 25% with melanoma, are being transduced into autologous T cells, the T cells are being expanded ex vivo and used to treat patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and metastatic melanoma [32]. This therapy has resulted in objective clinical responses in 4 of 6 patients with synovial cell sarcoma and five of 11 patients with melanoma [32].

Chimeric antigen T cell receptors (CAR) are also being used in adoptive cell therapy of cancer. One CAR that has been tested clinically is made up of the antigen recognition portion of CD19, the zeta chain of the T cell receptor and a portion of the co-stimulatory molecule CD28. Autologous T cells transduced with anti-CD19 CAR are cytolytic to B cell lymphoma cells that express CD19 [33]. While clinical trials of these genetically engineered T cells are just beginning, preliminary results have been encouraging [34].

In order to improve the effectiveness of adoptive cellular therapies with engineered T cells clinical investigators have turned to stem cell biology. While any population of CD8+ T cells can be genetically engineered; naïve, central memory or effector memory cells, engineered T cells produced from these three different types of T cells may not be equally effective in treating cancer. Restifo and colleagues have recently shown that naïve T cells are more capable then central or effector memory T cells of expressing TCR transgenes and in vitro expansion. Furthermore, expanded naïve cells express lower levels of markers of effector differentiation which has been associated with greater adoptive cellular therapy effectiveness and higher levels of CD27 and longer telomeres, which suggests that these cells have a greater in vivo proliferation potential [35]. The number of naïve T cells in the circulation varies among healthy subjects [35] and the levels of circulating native T cells are likely to be more variable among cancer patients due to prior cancer chemotherapy or the cancer itself. Patients who have had extensive chemotherapy may have very low levels of circulating T cells. As a result, investigators are working on cell reprogramming strategies to produce naïve and stem T cells for adoptive cellular therapy.

Patients are not served until new therapies are brought to the clinic. Fortunately, the clinical success of adoptive cellular therapies currently in clinical trials is driving the development of new cell production technologies that will make adoptive cellular therapy more feasible. Investigators at Baylor have found that gas-permeable flasks (e.g., G-Rex flasks, Wilson Wolf Manufacturing, New Brighton, MN) can be used to expand cytotoxic T cells to a much higher concentration than bags or traditional flasks [36]. Cell culture in G-Rex gas-permeable flasks requires approximately one-fifth the quantity of media, AB Serum, IL-2 and anti-CD3, and less equipment than culturing in bags or flasks. This reduction in culture volume and media is extremely important to producing the 10 to 40 × 109 cell used for adoptive cytotoxic T cell and NK cell therapy. Several groups are currently working to develop and validate methods to expand, TIL, T cells, engineered T cells and NK cell in G-Rex gas-permeable flasks. If the promising preliminary results of T and NK cell growth and expansion in G-Rex flasks continues, these methods will likely lead to the more widespread use many adoptive cellular therapies. Cell therapy laboratories are also working with the manufacturer of the G-Rex flasks, Wilson Wolf Manufacturing, to produce a larger gas-permeable flasks specifically designed for good manufacturing practice (GMP) cell growth that will further simply TIL, T cell and NK cell production.

Adoptive cell therapy requires cell growth and culture in multiple types of flasks and bags, with a variety of growth factors, cytokines and antibodies. Cell selection or depletion using monoclonal antibodies or elutriation is often used. Cells are sometimes transduced with retroviral or lentiviral vectors. Bringing these complex therapies to the clinic requires investigators to address a number of issues related to the safety and effectiveness of the final product. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is a critical partner in bringing safe and effective adoptive cellular therapies to the clinic and addressing the complex regulator issues related to cellular therapies. Representatives from the FDA should be included in forums that address important issues in the field of adoptive cellular therapy of cancer.

The growing clinical applications and success of adoptive cellular therapy of cancer has been due to the rapid evolution of immunology, gene therapy and stem cell biology and the translation of advances in these fields from the research laboratory to the clinic. The continued development of this field is dependent on the exchange of ideas across these diverse disciplines, the testing of new ideas in the research laboratory and in animal models, the development of new cellular therapies and GMP methods to produce these therapies, and the testing of new adoptive cell therapies in clinical trials. The Summit on Cell Therapy for Cancer will include a mix of perspectives, concepts and ideas related to adoptive cellular therapy that are not normally presented together at any single meeting. We hope that this novel assembly will generate new ideas and new collaborations and possibly increase the rate of advancement of this field.

References

Rosenberg SA, Packard BS, Aebersold PM, Solomon D, Topalian SL, Toy ST, Simon P, Lotze MT, Yang JC, Seipp CA: Use of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 in the immunotherapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1988, 319: 1676-1680. 10.1056/NEJM198812223192527.

Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, Raffeld M, Duray P, Seipp CA, Rogers-Freezer L, Morton KE, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Rosenberg SA: Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002, 298: 850-854. 10.1126/science.1076514.

Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, Royal RE, Kammula U, White DE, Mavroukakis SA, Rogers LJ, Gracia GJ, Jones SA, Mangiameli DP, Pelletier MM, Gea-Banacloche J, Robinson MR, Berman DM, Filie AC, Abati A, Rosenberg SA: Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 2346-2357. 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240.

Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Phan GQ, Citrin DE, Restifo NP, Robbins PF, Wunderlich JR, Morton KE, Laurencot CM, Steinberg SM, White DE, Dudley ME: Durable Complete Responses in Heavily Pretreted Patients with Metastatic Melanoma Using T Cell Transfer Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011

Zuliani T, David J, Bercegeay S, Pandolfino MC, Rodde-Astier I, Khammari A, Coissac C, Delorme B, Saiagh S, Dreno B: Value of large scale expansion of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in a compartmentalised gas-permeable bag: interests for adoptive immunotherapy. J Transl Med. 2011, 9: 63-10.1186/1479-5876-9-63.

Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Treves AJ, Zippel D, Itzhaki O, Hershkovitz L, Levy D, Kubi A, Hovav E, Chermoshniuk N, Shalmon B, Hardan I, Catane R, Markel G, Apter S, Ben-Nun A, Kuchuk I, Shimoni A, Nagler A, Schachter J: Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010, 16: 2646-2655. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0041.

Labarriere N, Pandolfino MC, Gervois N, Khammari A, Tessier MH, Dreno B, Jotereau F: Therapeutic efficacy of melanoma-reactive TIL injected in stage III melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002, 51: 532-538. 10.1007/s00262-002-0313-3.

Mackensen A, Meidenbauer N, Vogl S, Laumer M, Berger J, Andreesen R: Phase I study of adoptive T-cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cells for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 5060-5069. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1100.

Mitchell MS, Darrah D, Yeung D, Halpern S, Wallace A, Voland J, Jones V, Kan-Mitchell J: Phase I trial of adoptive immunotherapy with cytolytic T lymphocytes immunized against a tyrosinase epitope. J Clin Oncol. 2002, 20: 1075-1086. 10.1200/JCO.20.4.1075.

Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, Greenberg PD: Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 16168-16173. 10.1073/pnas.242600099.

Khammari A, Labarriere N, Vignard V, Nguyen JM, Pandolfino MC, Knol AC, Quereux G, Saiagh S, Brocard A, Jotereau F, Dreno B: Treatment of metastatic melanoma with autologous Melan-A/MART-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones. J Invest Dermatol. 2009, 129: 2835-2842. 10.1038/jid.2009.144.

Kolb HJ, Schattenberg A, Goldman JM, Hertenstein B, Jacobsen N, Arcese W, Ljungman P, Ferrant A, Verdonck L, Niederwieser D, van RF, Mittermueller J, de WT, Holler E, Ansari H: Graft-versus-leukemia effect of donor lymphocyte transfusions in marrow grafted patients. Blood. 1995, 86: 2041-2050.

Heslop HE: How I treat EBV lymphoproliferation. Blood. 2009, 114: 4002-4008. 10.1182/blood-2009-07-143545.

Bollard CM, Cooper LJ, Heslop HE: Immunotherapy targeting EBV-expressing lymphoproliferative diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008, 21: 405-420. 10.1016/j.beha.2008.06.002.

Gottschalk S, Rooney CM, Heslop HE: Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Annu Rev Med. 2005, 56: 29-44. 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104727.

Maslak PG, Dao T, Krug LM, Chanel S, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, Zhang R, Wolchok JD, Yuan J, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Berman E, Weiss M, Jurcic J, Frattini MG, Scheinberg DA: Vaccination with synthetic analog peptides derived from WT1 oncoprotein induces T-cell responses in patients with complete remission from acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010, 116: 171-179. 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250993.

Van T V, Van d V, Van D A, Cools N, Anguille S, Ladell K, Gostick E, Vermeulen K, Pieters K, Nijs G, Stein B, Smits EL, Schroyens WA, Gadisseur AP, Vrelust I, Jorens PG, Goossens H, de V I, Price DA, Oji Y, Oka Y, Sugiyama H, Berneman ZN: Induction of complete and molecular remissions in acute myeloid leukemia by Wilms' tumor 1 antigen-targeted dendritic cell vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010, 107: 13824-13829. 10.1073/pnas.1008051107.

Molldrem JJ, Clave E, Jiang YZ, Mavroudis D, Raptis A, Hensel N, Agarwala V, Barrett AJ: Cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a nonpolymorphic proteinase 3 peptide preferentially inhibit chronic myeloid leukemia colony-forming units. Blood. 1997, 90: 2529-2534.

Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Vloon AP, Essahsah F, Fathers LM, Offringa R, Drijfhout JW, Wafelman AR, Oostendorp J, Fleuren GJ, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ: Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009, 361: 1838-1847. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810097.

Ly LV, Sluijter M, Versluis M, Luyten GP, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ, Jager MJ, van HT: Peptide vaccination after T-cell transfer causes massive clonal expansion, tumor eradication, and manageable cytokine storm. Cancer Res. 2010, 70: 8339-8346. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2288.

McKenna DH, Sumstad D, Bostrom N, Kadidlo DM, Fautsch S, McNearney S, Dewaard R, McGlave PB, Weisdorf DJ, Wagner JE, McCullough J, Miller JS: Good manufacturing practices production of natural killer cells for immunotherapy: a six-year single-institution experience. Transfusion. 2007, 47: 520-528. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01145.x.

Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McNearney SA, Yun GH, Fautsch SK, McKenna D, Le C, DeFor TE, Burns LJ, Orchard PJ, Blazar BR, Wagner JE, Slungaard A, Weisdorf DJ, Okazaki IJ, McGlave PB: Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood. 2005, 105: 3051-3057. 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2974.

Geller MA, Cooley S, Judson PL, Ghebre R, Carson LF, Argenta PA, Jonson AL, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Curtsinger J, McKenna D, Dusenbery K, Bliss R, Downs LS, Miller JS: A phase II study of allogeneic natural killer cell therapy to treat patients with recurrent ovarian and breast cancer. Cytotherapy. 2011, 13: 98-107. 10.3109/14653249.2010.515582.

Bachanova V, Burns LJ, McKenna DH, Curtsinger J, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Lindgren BR, Cooley S, Weisdorf D, Miller JS: Allogeneic natural killer cells for refractory lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010, 59: 1739-1744. 10.1007/s00262-010-0896-z.

Berg M, Lundqvist A, McCoy P, Samsel L, Fan Y, Tawab A, Childs R: Clinical-grade ex vivo-expanded human natural killer cells up-regulate activating receptors and death receptor ligands and have enhanced cytolytic activity against tumor cells. Cytotherapy. 2009, 11: 341-355. 10.1080/14653240902807034.

Berg M, Childs R: Ex-vivo expansion of NK cells: what is the priority--high yield or high purity?. Cytotherapy. 2010, 12: 969-970. 10.3109/14653249.2010.536216.

Castiello L, Sabatino M, Jin P, Clayberger C, Marincola FM, Krensky AM, Stroncek DF: DC maturation strategies and related pathways: a transcriptional veiw. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010,

Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Leen AM, Weiss H, Straathof KC, Carrum G, Khalil M, Wu MF, Huls MH, Chang CC, Gresik MV, Gee AP, Brenner MK, Rooney CM, Heslop HE: Complete responses of relapsed lymphoma following genetic modification of tumor-antigen presenting cells and T-lymphocyte transfer. Blood. 2007, 110: 2838-2845. 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091280.

Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA: Adoptive cell therapy: genetic modification to redirect effector cell specificity. Cancer J. 2010, 16: 336-341. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eb3879.

Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Royal RE, Sherry RM, Wunderlich JR, Lee CC, Restifo NP, Schwarz SL, Cogdill AP, Bishop RJ, Kim H, Brewer CC, Rudy SF, VanWaes C, Davis JL, Mathur A, Ripley RT, Nathan DA, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA: Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009, 114: 535-546. 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714.

Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA: Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006, 314: 126-129. 10.1126/science.1129003.

Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Nahvi AV, Helman LJ, Mackall CL, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Restifo NP, Raffeld M, Lee CC, Levy CL, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Schwarz SL, Laurencot C, Rosenberg SA: Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29: 917-924. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537.

Kochenderfer JN, Yu Z, Frasheri D, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA: Adoptive transfer of syngeneic T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor that recognizes murine CD19 can eradicate lymphoma and normal B cells. Blood. 2010, 116: 3875-3886. 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265041.

Kochenderfer JN, Wilson WH, Janik JE, Dudley ME, Stetler-Stevenson M, Feldman SA, Maric I, Raffeld M, Nathan DA, Lanier BJ, Morgan RA, Rosenberg SA: Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010, 116: 4099-4102. 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931.

Hinrichs CS, Borman ZA, Gattinoni L, Yu Z, Burns WR, Huang J, Klebanoff CA, Johnson LA, Kerkar SP, Yang S, Muranski P, Palmer DC, Scott CD, Morgan RA, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP: Human effector CD8+ T cells derived from naive rather than memory subsets possess superior traits for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2011, 117: 808-814. 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286286.

Vera JF, Brenner LJ, Gerdemann U, Ngo MC, Sili U, Liu H, Wilson J, Dotti G, Heslop HE, Leen AM, Rooney CM: Accelerated production of antigen-specific T cells for preclinical and clinical applications using gas-permeable rapid expansion cultureware (G-Rex). J Immunother. 2010, 33: 305-315. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181c0c3cb.

Acknowledgements

This summit is sponsored by Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) in conjunction with the following participating organizations: AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks), American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy (ASGCT) and Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network (CITN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CJMM and JJO helped plan and write the manuscript. DFS helped plan the manuscript and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Melief, C.J., O'Shea, J.J. & Stroncek, D.F. Summit on cell therapy for cancer: The importance of the interaction of multiple disciplines to advance clinical therapy. J Transl Med 9, 107 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-9-107

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-9-107