Abstract

Background

Extragonadal localization of germ cell tumors (GCTs) is rare; to the best of our knowledge, a location in the soft tissue of the arm has never been previously reported in the literature.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 37-year-old man who presented with a primary malignant mixed non-seminomatous GCT (teratocarcinoma variety) in the right arm, treated by a combination of cisplatin-based chemotherapy and surgery. After 18 months of close follow-up, no locoregional recurrence or distant metastases have been detected.

Conclusions

A combination of chemotherapy and surgery is the most appropriate treatment strategy for extragonadal GCTs, to ensure both local and systemic control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) are classified as extragonadal if there is no evidence of a primary tumor in either the testes or ovaries [1]; they typically arise in midline locations. In adults, the most common sites, in order of frequency, are the anterior mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and the pineal and suprasellar regions. To date, there have been no reported cases of germ cell tumors arising in the arm.

The aim of the present work was not only to report what is to the best of our knowledge the first observation of a mixed non-seminomatous GCT of the arm, but to also increase exposure of the various hypotheses that could explain this unusual location. We also discuss the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this entity.

Case presentation

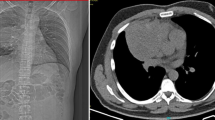

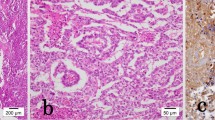

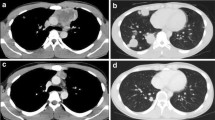

A 37-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of painless swelling of the right arm with a gradual increase in size. A physical examination was normal except for a well circumscribed non-tender mass in the upper two-thirds of the right arm and multiple lymph nodes in the right axilla. Imaging revealed a 53 × 40 mm diameter soft tissue mass that was hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI in the posterior compartment of the right arm, with no bone or vascular invasion (Figures 1 and 2). Surgical biopsy of the mass and axillary lymph node excision were performed; the laboratory received two fragments with soft consistency, measuring 2 × 1 × 0.3 cm and 2.5 × 1 × 0.5 cm. Histopathological examination showed a desembryoplastic multitissular tumor, containing a sarcomatous component constituted by spindle cells and organized in bundles with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. There was also an immature and malignant neuroglial component, and this tumor additionally showed epithelial structures with squamous or glandular differentiation; some cells were compatible with embryonal carcinoma. These various tissular structures were very confluent, without transition. Atypical immature cartilage and bone components were observed associated with necrosis. The axillary lymph node excised was metastatic. There was no need for immunohistochemical staining to confirm the diagnosis of malignant mixed GCT (teratocarcinoma variety) (Figure 3). Testicular palpation and ultrasonography results were normal. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no abnormalities. Serum α-fetoprotein (AFP), β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were all within normal ranges. The patient received four courses of chemotherapy (bleomycin 30 units intravenous injection, days 1, 8, and 15; etoposide 100 mg/m2 intravenously, days 1 through 5; cisplatin 20 mg/m2 intravenously, days 1 through 5). A clinical evaluation of response at the end of chemotherapy showed a stable disease. Then, 1 month later, a wide excision with axillary dissection was performed; the excised tumor was partially well circumscribed and measured 57 × 42 × 38 mm and had a uniform, yellowish, solid, and partially nodular appearance on the cut surface. Final pathology revealed the same histological aspect as observed in the biopsy but did not revealed tumoral necrotic patterns. All surgical margins were free, and one of six lymph nodes identified was involved without extracapsular spread (Figures 4 and 5). Two further cycles of chemotherapy using the same protocol were added. At 18 months of close follow-up, no locoregional recurrence or distant metastases have been detected.

Discussion

Primary GCTs of extragonadal origin comprise 3% to 5% of all germ cell tumors. Extragonadal GCTs arise from midline structures [2, 3]. A case of extragonadal malignant teratoma of the extremities has been reported by Chinoy et al. [4]. Herein, we describe what is to the best of our knowledge the first reported case of a mixed non-seminomatous germ cell tumor (teratocarcinoma) located in the soft tissue of the right arm. The histogenesis of extragonadal GCTs is not clearly defined: two competing hypotheses have been proposed, but there are inadequate data to determine which, if either, is correct. The first hypothesis is that extragonadal GCTs are derived from primordial germ cells that fail to complete the normal migration along the urogenital ridge to the gonadal ridges during embryonal development. This may be due to an abnormality in the primordial germ cell itself or in its microenvironment [5]. The second main hypothesis is that germ cells transformed in the testes undergo reverse migration [6]. This hypothesis is supported by genetic data suggesting that extragonadal GCTs and testicular GCTs share a common cell of origin [7, 8]. The etiology of extragonadal GCTs is unknown; in rare cases, they have been associated with Klinefelter syndrome [9–12]. A biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis and treatment of extragonadal GCTs; the majority of patients have clear evidence of germ cell features or teratoma, while a small subset have a poorly differentiated tumor without distinctive germ cell features. In our patient’s case the diagnosis of teratocarcinoma was established on the basis of pathological examination, which showed the combination of teratoma and embryonal carcinoma [13]. However it is important to note that the term teratocarcinoma has largely been abandoned, and these tumors are referred to as a malignant mixed GCT, with a description of the specific germ cell tumor elements present. Once the diagnosis of a germ cell tumor has been established, a primary testicular tumor must be excluded. Testicular palpation is insufficient to exclude a testicular primary; ultrasonography should be performed in all patients [14]. It may be difficult to distinguish true extragonadal GCTs from metastatic tumors in which the primary testicular lesion has regressed [15–17]. Extragonadal non-seminomatous GCT should be considered in the differential diagnosis of histologically poorly differentiated cancer and of neoplasms of unknown primary site, particularly in young men with midline disease. In our patient’s case another uncommon differential diagnosis must be evocated: it is a soft tissue metastasis from primary testicular cancer [18].

Because an extragonadal GCT may be curable with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, many recommend that the diagnostic evaluation in such cases should include measurement of the serum tumor markers AFP and β-HCG, immunohistochemical assessment of the biopsy [19], and cytogenetic analysis for abnormalities of chromosome arm 12p [20]. However, isochromosome 12p is not pathognomonic of GCTs [21, 22]. Mixed GCTs, mainly teratomas with additional malignant components (other germ cell tumors, carcinomas or sarcomas), have been reported to be more aggressive. More than 50% of those patients died within 2 years of follow-up due to local invasion or distant metastases (lymph nodes, liver, lung, heart, bone, and brain) [23, 24]. A multimodality approach is generally used, utilizing chemotherapy initially followed by surgery for any residual mass. We recommend four cycles of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy as the initial therapy, rather than surgery or radiation therapy; for patients with a residual mass following initial chemotherapy, we recommend complete surgical resection if technically feasible. If viable malignancy is identified, two additional cycles of chemotherapy should be given [25, 26].

Conclusions

Regardless of the location, the therapeutic approach of extragonadal GCTs should be multidisciplinary, combining systemic chemotherapy and surgery.

The decision of the number and timing of cycles of chemotherapy depends on the disease stage and histological analysis of the surgical specimen.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report. A copy of the written consent is available for review from the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Misc

Hicham Ait Benali and lssam Lalya are equally contributed.

References

Droz JP, Horwich A: Extragonadal germ cell tumors. Comprehensive Textbook of Genitourinary Oncology. Edited by: Vogelzang NJ, Scardino PT, Shipley WU, Doffey DS. 2000, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, New York, NY, 2

Morse MJ, Whitmore WF: Neoplasms of the testis. Campbell’s Urology. Edited by: Walsh PC, Gittes RF, Perlmutter AD, Stamey TA. 1986, WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia, PA, 1535-5

Buskirk SS, Evans RG, Farrow G, Earle JP: Primary retroperitoneal seminoma. Cancer. 1934, 1982: 49-

Chinoy RF, Soman CS, Swaroop D, Badwar RA: Extragonadal malignant teratoma of the foot. Indian J Cancer. 1992, 29: 96-99.

Glenn OA, Barkovich AJ: Intracranial germ cell tumors: a comprehensive review of proposed embryologic derivation. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996, 24: 242-

Chaganti RS, Houldsworth J: Genetics and biology of adult human male germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 1475-

Hailemariam S, Engeler DS, Bannwart F, Amin MB: Primary mediastinal germ cell tumor with intratubular germ cell neoplasia of the testis-further support for germ cell origin of these tumors: a case report. Cancer. 1997, 79: 1031-

Chaganti RS, Rodriguez E, Mathew S: Origin of adult male mediastinal germ-cell tumours. Lancet. 1994, 343: 1130-

Chen CK, Chang YL, Jou ST, Tseng YT, Lee YC: Treatment of mediastinal immature teratoma in a child with precocious puberty and Klinefelter’s syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1906, 2006: 82-

Phowthongkum P: The second case of de novo intracranial germinoma association with Klinefelter’s syndrome. Surg Neurol. 2006, 66: 332-

Aguirre D, Nieto K, Lazos M, Peña YR, Palma I, Kofman-Alfaro S, Queipo G: Extragonadal germ cell tumors are often associated with Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Pathol. 2006, 37: 477-

Völkl TM, Langer T, Aigner T, Greess H, Beck JD, Rauch AM, Dörr HG: Klinefelter syndrome and mediastinal germ cell tumors. Am J Med Genet A. 2006, 140: 471-

Gonzalez-Crussi F: Extragonadal teratomas. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Volume 18. Edited by: Hartmann WH, Cowan WR. 1982, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1-49.

Bšhle A, Studer UE, Sonntag RW, Scheidegger JR: Primary or secondary extragonadal germ cell tumors?. J Urol. 1986, 135: 939-

McAleer JJ, Nicholls J, Horwich A: Does extragonadal presentation impart a worse prognosis to abdominal germ-cell tumours?. Eur J Cancer. 1992, 28A: 825-

Comiter CV, Renshaw AA, Benson CB, Loughlin KR: Burned-out primary testicular cancer: sonographic and pathological characteristics. J Urol. 1996, 156: 85-

Balzer BL, Ulbright TM: Spontaneous regression of testicular germ cell tumors: an analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006, 30: 858-

Bilici A, Ustaalioglu BB, Seker M, Kayahan S: Case report:soft tissue metastasis from immature teratoma of the testis: second case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010, 468: 2541-2544.

Cheng L: Establishing a germ cell origin for metastatic tumors using OCT4 immunohistochemistry. Cancer. 2006, 2004: 101-

Motzer RJ, Rodriguez E, Reuter VE, Bosl GJ, Mazumdar M, Chaganti RS: Molecular and cytogenetic studies in the diagnosis of patients with poorly differentiated carcinomas of unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol. 1995, 13: 274-

Heinonen K, Rao PN, Slack JL, Cruz J, Bloomfield CD, Mrózek K: Isochromosome 12p in two cases of acute myeloid leukaemia without evidence of germ cell tumour. Br J Haematol. 1996, 93: 677-

Genet P, Mossafa H, Pulik M: Isochromosome 12p in mediastinal centroblastic lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2000, 108: 885-

Moran CA, Suster S: Primary germ cell tumors of the mediastinum: Analysis of 322 cases with special emphasis on teratomatous lesions and a proposal for histopathologic classification and clinical staging. Cancer. 1997, 80: 681-690.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermerlink HK, Harris CC: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 2004, IARC Press, Lyon, France

Wright CD, Kesler KA, Nichols CR: Primary mediastinal non seminomatous germ cell tumors, Results of a multimodality approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990, 99: 210-217.

Chetaille B, Massard G, Falcozb PE: Mediastinal germ cell tumors: anatomopathology, classification, teratomas and malignant tumors. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2010, 66: 63-70.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IL and HA performed the literature review, composed the case report and wrote the manuscript. MA and AB were involved with conception and design and collection and assembly of data. BEK and MA analyzed and interpreted the anatomopathology findings. SB, NB and ME approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Benali, H.A., Lalya, l., Allaoui, M. et al. Extragonadal mixed germ cell tumor of the right arm: description of the first case in the literature. World J Surg Onc 10, 69 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-10-69

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-10-69