Abstract

Background

Topiramate is approved for the prophylaxis (prevention) of migraine headache in adults. The most common adverse events in the three pivotal, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials were paresthesia, fatigue, cognitive impairment, anorexia, nausea, and taste alteration. In these trials, topiramate 100 mg/d significantly improved Migraine-Specific Questionnaire (MSQ) scores versus placebo (p < 0.001). The MSQ measures how much migraine limits/interrupts daily performance. Pooled analyses of pivotal trial data were conducted to further assess how topiramate 100 mg/d affects daily activities and patient functioning.

Methods

Mean MSQ and Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) change scores (baseline to each double-blind assessment point) were calculated for pooled intent-to-treat (ITT) patients. Additionally, pooled ITT patients receiving topiramate 100 mg/d or placebo were combined and divided into two responder groups according to percent reduction in monthly migraine frequency: < 50% responders or ≥ 50% responders. Between-group differences were assessed using analysis of covariance.

Results

Of 756 patients (mean age 39.8 years, 86% female), 384 received topiramate 100 mg/d and 372 placebo. Topiramate significantly improved all three MSQ domains throughout the double-blind phase versus placebo (p = 0.024 [week 8], p < 0.001 [weeks 16 and 26] for role prevention; p < 0.001 for role restriction and emotional function [all time points]). Topiramate 100 mg/d significantly improved SF-36 physical component scores (PCS) throughout the double-blind phase versus placebo (p < 0.001, all time points) and significantly improved mental component scores (MCS) at week 26 (p = 0.043). The greatest topiramate-associated improvements on SF-36 subscales were seen for bodily pain and general health perceptions (p < 0.05; weeks 8, 16, and 26), and physical functioning, vitality, role-physical, and social functioning (p < 0.05; weeks 16 and 26). Significantly greater improvements in all three MSQ domains, as well as the PCS and MCS of SF-36, were observed for ≥ 50% responders versus < 50% responders (p < 0.001). Significantly greater percentages of topiramate-treated patients were ≥ 50% responders versus placebo (46% versus 23%; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Topiramate 100 mg/d significantly improved daily activities and patient functioning at all time points throughout the double-blind phase. Daily function and health status significantly improved for those achieving a ≥ 50% migraine frequency reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Migraine is a significant detriment to daily functioning and productivity during, but also to a certain extent before and after, attacks. Migraine preventive therapy should improve negative, disease-related outcomes, provided that appropriate diagnostic criteria and management guidelines are followed. Although approximately 11.5 million U.S. patients with migraine could benefit from preventive therapy (approximately 40% of all U.S. patients with migraine), only one in five currently receives this type of treatment [1, 2].

In three large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-month, migraine prevention trials [3–6], topiramate 100 mg/d (50 mg bid) was associated with a significant and sustained decrease in mean monthly migraine frequency, observed as early as the first month of therapy. Topiramate 100 mg/d was generally well tolerated and is recommended as the target dose for most patients with migraine [3–6]. Recently, safety and tolerability data for these three trials was pooled and analyzed [6]. The most common adverse events in topiramate-treated patients in these trials were paresthesia (50.5%), fatigue (15.0%), anorexia (14.5%), upper respiratory infection (14.0%), cognitive impairment (13.7%), nausea (13.2%), diarrhea (11.1%), and weight decrease (9.1%). Adverse events were mostly mild to moderate in severity and occurred more frequently during titration to target doses [7]. For a more detailed analysis of safety and tolerability data, the published trials can be reviewed [3–5].

Pooled Migraine-Specific Questionnaire (MSQ) data from the three pivotal trials showed that topiramate 100 mg/d significantly improved each of the three dimensions of MSQ at end point compared with placebo [8]. In addition, analyses of the effects of topiramate migraine preventive therapy on the two activity-related domains of the MSQ and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36), prospectively designated as outcome measures in the North American pivotal trials, were recently published [9, 10]. Improvements in patient-reported MSQ outcomes were significantly better for patients receiving topiramate than for those receiving placebo. In addition, improvements in the selected MSQ and SF-36 domains were significantly correlated with the decrease in mean monthly migraine frequency observed with topiramate treatment [9, 10].

To further assess the impact of topiramate on daily activities and function over time, results derived from both the MSQ and the generic SF-36 were analyzed over the three time points during the 26-week double-blind phase when the questionnaires were administered. Additionally, we sought to determine the relationship between improvement in these quality of life measures and reductions in migraine frequency.

Methods

Study design

The overall study design for patients receiving topiramate 100 mg/d or placebo in the three similar placebo-controlled pivotal trials has been described previously [3–5].

Patients

Patients were required to have three to 12 migraine periods (one period equals 24 hours with migraine; ie, migraine frequency) and no more than 15 headache days during the 28-day prospective baseline phase. Patients were allowed to continue taking specific agents for acute treatment of migraine, but those who overused acute medications were excluded from the placebo-controlled trials [3, 4], except in the trial with propranolol as an active comparator [5]. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population was identified as those who received ≥ 1 post-baseline dose of study medication and contributed efficacy data during the double-blind phase. Demographics for the pooled ITT population are presented in Table 1.

Outcome measures

MSQ and SF-36 data were collected at baseline and at weeks 8, 16, and 26. End point was defined as the last available post-baseline observation in the double-blind phase. The 14-item MSQ assesses the degree to which migraine limits and interrupts daily performance and is divided into three domains: Role Restriction assesses the degree to which migraine limits performance of daily life, social life, and work (seven questions); Role Prevention assesses the degree to which migraine prevents performance of daily life, social life, and work (four questions); and Emotional Function measures the feeling of frustration and helplessness as a result of migraine (three questions). All three MSQ domains are scored from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better functioning [11]. The reliability and validity of the MSQ has been demonstrated in numerous studies [11–13].

The generic SF-36 is a widely used, validated tool that assesses the general impact of medical disorders on multiple domains of patient daily activities and function. It consists of two aggregate summary measures (scales) and eight domain-specific measures (subscales) and is scored from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater function. A change of five points on the SF-36 is generally considered clinically meaningful.

The change in mean MSQ or SF-36 scores from baseline through the double-blind phase was assessed for pooled ITT patients. Baseline values for MSQ and SF-36 are summarized in Table 2. In an additional analysis reflecting International Headache Society clinical trial guidelines, pooled ITT patients on topiramate 100 mg/d or placebo were combined and divided into groups based on whether they had experienced ≥ 50% or < 50% reductions in monthly migraine frequency at the study end point. Changes in MSQ and SF-36 scores from baseline to end point were compared between these responder groups.

Statistical analysis

Between-group differences were analyzed using an analysis of covariance model, with treatment and protocol as main effects and respective baseline values as covariates. The responder rate was analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusting for protocol and analysis center. For these exploratory post hoc analyses, the statistical methodologies used to assess differences between groups were not adjusted for multiplicity. Descriptive statistics were used for the demographic analysis.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients

Demographics and baseline MSQ and SF-36 scores for the pooled ITT population are presented in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 756 patients given topiramate 100 mg/d (n = 384) or placebo (n = 372) were included in this analysis. The mean (± SD) ages of the patients in these trials ranged from 38.3 (± 12.0) years to 40.6 (± 11.0) years (range, 12 to 70 years). The majority of patients in the three trials were female (≥ 76%) and Caucasian (≥ 88%). The mean (± SD) MSQ scores at baseline (± SD) ranged from 48.1 (± 17.2) to 68.6 (± 18.9). The mean (± SD) SF-36 scores at baseline ranged from 42.9 (± 9.1) to 82.1 (± 19.4). Pooled ITT patients receiving topiramate 100 mg/d or placebo were combined and divided into two response groups < 50% response (n = 492) or ≥ 50% response (n = 262).

Outcome measures

MSQ scores

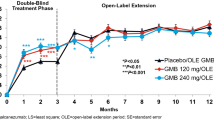

Topiramate 100 mg/d significantly improved the mean scores from baseline for all three domains (Role Restriction, Role Prevention, and Emotional Function) of the MSQ at weeks 8, 16, and 26, and at end point compared with placebo (p < 0.001 for all, except Role Prevention p = 0.024 at week 8) (Figures 1, 2, 3).

SF-36 scores

Topiramate treatment resulted in significant improvement compared with placebo at week 26 on all SF-36 subscales except Role-Emotional (Figure 4, Table 3). Topiramate treatment significantly improved the SF-36 physical component scores throughout the double-blind phase compared with placebo (p < 0.001, all time points) and significantly improved the mental component scores at week 26 (p = 0.043). Maximal topiramate-associated improvements on SF-36 subscales were seen for Bodily Pain and General Health Perceptions (p < 0.05; weeks 8, 16, and 26) and Physical Functioning, Vitality, Role-Physical, and Social Functioning (p < 0.05; weeks 16 and 26).

Radar plots of absolute mean Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) scores at baseline and week 26. PBO = placebo; TPM = topiramate; PF = physical functioning; BP = bodily pain; VT = vitality; GH = general health perceptions; RE = role-emotional; RP = role-physical; MH = mental health; SF = social functioning; ITT = intent-to-treat; TPM = topiramate. All p values versus PBO from baseline to week 26: PF, p = 0.023; BP, p < 0.001; VT, p < 0.001; GH, p = 0.027; RP, p = 0.018); MH, p = 0.034; SF, p = 0.010.

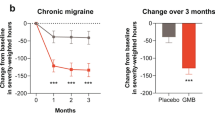

Responder analysis

Significantly greater percentages of patients on topiramate 100 mg/d were ≥ 50% responders versus placebo (46% versus 23%; p < 0.001, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test). The individual responder rates for the three pivotal studies were: 54.0% versus 22.6% placebo (p < 0.001) in Silberstein et al. [3]; 49% vs. 23% placebo (p < 0.001) in Brandes et al. [4]; and 37% versus 22% placebo (p < 0.01) in Diener et al. [5]. Baseline MSQ and SF-36 domain scores for those ITT patients who experienced ≥ 50% or < 50% reductions in monthly migraine frequency at end point (last observation carried forward), regardless of study medication, are presented in Table 4; scores were generally similar between the two responder groups. The ≥ 50% responders had significantly higher improvements from baseline to double-blind end point for all three MSQ domains compared with the < 50% responders (Figure 5; p < 0.001). In addition, the ≥ 50% responders had significantly improved SF-36 Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary scores and significantly improved scores on seven of eight SF-36 subscales at end point compared with the < 50% responders (Figure 6). Of 262 patients identified as responders, 177 (67.6%) were given topiramate and 85 (32.4%) were on placebo.

Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) domain scores at end point (last observation carried forward) for pooled intent-to-treat subjects with *#8805; 50% or < 50% reductions in monthly migraine frequency. *p < 0.001; † P = 0.007; ‡p = 0.013; §p = 0.019, ||p = 0.026 versus < 50% responders. PF = physical functioning; BP = bodily pain; VT = vitality; GH = general health perceptions; RE = role-emotional; RP = role-physical; MH = mental health; SF = social functioning; PCS = physical component summary; MCS = mental component summary.

Discussion

Studies detailing the specific impact of migraine preventive therapy on daily activities are limited despite the obvious clinical relevance of such information. The results of this analysis of pooled MSQ and SF-36 data from three pivotal topiramate migraine prevention trials demonstrated that topiramate 100 mg/d was associated with a significant and sustained improvement in daily activities and function for up to 6 months. All MSQ domain scores were significantly improved by week 8 (first health-related quality-of-life assessment point post baseline). The MSQ results indicated that patients on topiramate 100 mg/d had significantly less migraine-related disruption of daily activities and less frustration and feelings of helplessness due to migraine than those on placebo. Topiramate 100 mg/d was also associated with significant improvements in seven of eight subscales of the SF-36. Topiramate-associated improvements on the disease-specific MSQ were stronger than the generic SF-36 scale, which is not surprising given that generic scales tend to measure constructs that are not necessarily affected by a specific disease. In addition, the MSQ does not fully assess the impact of adverse events of drug treatment and may contribute to the higher change scores observed following topiramate treatment.

The Genetic Epidemiology of Migraine study revealed that patient function was inversely related to migraine attack frequency (p < 0.0002), with those suffering from a high frequency of attacks reporting diminished physical, mental, and social functioning [14]. In this analysis, patients who experienced ≥ 50% decreases in monthly migraine frequency on either topiramate or placebo (≥ 50% responders) experienced significantly more improvement in their functioning levels than those patients who experienced < 50% decreases in monthly migraine frequency. This result indicates that reduced monthly migraine frequency is associated with improved patient ability to carry out daily activities, a result supported by earlier clinical trials [6]. Active treatment is superior to placebo, with topiramate 100 mg/d associated with a significantly higher percentage of ≥ 50% responders (46%) than placebo (23%, p < 0.001, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test) in a pooled analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials [6].

The results of this post-hoc study are consistent with pre-specified analyses from two trials that evaluated MSQ and SF-36 outcomes to measure changes in daily activities and function related to topiramate treatment [9, 10]. Results of an analysis conducted by Silberstein and colleagues found that in the ITT population (N = 469), topiramate (50 mg/d, 100 mg/d, and 200 mg/d) significantly improved mean MSQ Role Restriction domain scores versus placebo (p = 0.035; p < 0.001; p = 0.001, respectively) [9]. Improvements in mean MSQ Role Prevention scores were significant versus placebo only for topiramate 100 mg/d (p = 0.045). SF-36 Role-Physical and SF-36 Vitality domain scores chosen as outcome measures improved but were not significant versus placebo for topiramate 100 mg/d and 200 mg/d. Changes in these MSQ and SF-36 domain scores significantly correlated with changes in mean monthly migraine frequency.

In an analysis conducted by Brandes and colleagues [10], patients receiving topiramate, 100 or 200 mg/d, had significantly reduced mean monthly migraine frequency (p = 0.008 and p < 0.001, respectively) compared with placebo, but not patients receiving topiramate 50 mg/d (p = 0.48). Topiramate significantly improved mean MSQ Role Restriction domain scores (50 mg/d [p = 0.02], 100 mg/d [p < 0.001], and 200 mg/d [p < 0.001]) and mean MSQ Role Prevention domain scores (50 mg/d [p = 0.007], 100 mg/d [p = 0.001], and 200 mg/d [p = 0.002]) versus placebo. Topiramate 100 and 200 mg/d significantly improved mean SF36 Role-Physical domain scores versus placebo (p = 0.02). Changes in prospectively designated domain scores were significantly correlated with changes in mean monthly migraine frequency (p ≤ 0.001, MSQ domains; p ≤ 0.002, SF-36 domains).

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that preventive treatment of migraine with topiramate 100 mg/d improves patients' ability to carry out daily activities as early as week 8, and the effect is maintained during 6-month treatment. Information about such patient-centered outcomes is likely to be of interest to migraine patients and clinicians making treatment decisions, but has not been routinely evaluated for most migraine preventive treatments. Reducing the considerable burden and disability of migraine through effective treatment may improve patients' overall functional capacity.

Abbreviations

- ITT:

-

= intent-to-treat

- MSQ:

-

= Migraine-Specific Questionnaire

- SF-36:

-

= Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36

- PCS:

-

= physical component summary

- MCS:

-

= mental component summary

References

Silberstein S, Diamond S, Loder E, Reed ML, Lipton RB: Prevalence of migraine sufferers who are candidates for preventive therapy: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache 2005, 45: 770–771. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.00250.x

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF, AMPP Advisory Group: Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007, 68: 343–349. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21

Silberstein SD, Neto W, Schmitt J, Jacobs D, MIGR-001 Study Group: Topiramate in migraine prevention: results of a large controlled trial. Arch Neurol 2004, 61: 490–495. 10.1001/archneur.61.4.490

Brandes JL, Saper JR, Diamond M, Couch JR, Lewis DW, Schmitt J, Neto W, Schwabe S, Jacobs D, MIGR-002 Study Group: Topiramate for migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 291: 965–973. 10.1001/jama.291.8.965

Diener HC, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dahlof C, Lainez MJ, Sandrini G, Wang SJ, Neto W, Vijapurkar U, Doyle A, Jacobs D, MIGR-003 Study Group: Topiramate in migraine prophylaxis – results from a placebo-controlled trial with propranolol as an active control. J Neurol 2004, 251: 943–950. 10.1007/s00415-004-0464-6

Bussone G, Diener HC, Pfeil J, Schwalen S: Topiramate 100 mg/day in migraine prevention: a pooled analysis of double-blind randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract 2005, 59: 961–968. 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00612.x

Adelman J, Freitag FG, Lainez MJA, Hulihan J, Shi Y: Analysis of safety and tolerability data obtained from over 1500 patients receiving topiramate for migraine prevention in controlled trials. Pain Med, in press.

Diamond M, Dahlöf C, Papadopoulos G, Neto W, Wu SC: Topiramate improves health-related quality of life when used to prevent migraine. Headache 2005, 45: 1023–1030. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05183.x

Silberstein SD, Loder E, Forde G, Papadopoulos G, Fairclough D, Greenberg S: The impact of migraine on daily activities: effect of topiramate compared with placebo. Curr Med Res Opin 2006, 22: 1021–1019. 10.1185/030079906X104731

Brandes JL, Kudrow DB, Rothrock JF, Rupnow MFT, Fairclough D, Greenberg S: Assessing the ability of topiramate to improve the daily activities of patients with migraine. Mayo Clin Proc 2006, 81: 1–9.

Martin BC, Pathak DS, Sharfman MI, Adelman JU, Taylor F, Kwong WJ, Jhingran P: Validity and reliability of the migraine-specific quality of life questionnaire (MSQ Version 2.1). Headache 2000, 40: 204–215. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00030.x

Jhingran P, Osterhaus JT, Miller DW, Lee JT, Kirchdoerfer L: Development and validation of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Headache 1998, 38: 295–302. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3804295.x

Jhingran P, Davis SM, LaVange LM, Miller DW, Helms RW: MSQ: Migraine-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. Further investigation of the factor structure. Pharmacoeconomics 1998, 13: 707–717. 10.2165/00019053-199813060-00007

Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Tijhuis M, Groenen SM, Picavet HS, Launer LJ: The impact of migraine on quality of life in the general population: the GEM study. Neurology 2000, 55: 624–629.

Acknowledgements

Research and analysis of the pivotal trials was supported by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, LLC, Raritan, NJ. Pooled analysis and writing of this manuscript was supported by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Titusville, NJ., with statistical analysis provided by Lian Mao. Editorial services were provided by Phase Five Communications Inc., New York, NY.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Professor Carl Dahlöf has been a consultant/scientific advisor on advisory boards, clinical trials, and investigator-initiated trials and a speaker for: Allergan, Almirall Prodesfarma, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Merck, Lilly, NMT Medical Inc., Novartis, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Pharmacia, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and St Jude Medical EMEAC.

Elizabeth Loder has had no financial relationship with any pharmaceutical company since July 2006, except grant support from NMT for a clinical trial. She has been a speaker, received grant support, or been a consultant for: OrthoMcNeil, Endo, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Allergan. She serves on the Board of Directors of the American Headache Society, the Executive Council of the International Headache Society, and the Board of the Headache Cooperative of New England.

Merle Diamond has served as a consultant and/or conducted research with AstraZeneca, Ortho-McNeil Neurologics, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Co., Pfizer, and Primary Care Network.

Marcia Rupnow is a full-time salary employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

George Papadopoulos was an employee of J&J Pharmaceutical Services at the time of study completion.

Lian Mao is a full-time salary employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Authors' contributions

All the authors were study investigators and contributed to the development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahlöf, C., Loder, E., Diamond, M. et al. The impact of migraine prevention on daily activities: a longitudinal and responder analysis from three topiramate placebo-controlled clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes 5, 56 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-56

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-56