Abstract

Background

Persistent vascular inflammation has been implicated as an important cause for a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in HIV-infected adults. In several populations at high risk for CVD, vascular 18Fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) uptake quantified using 3D-positron emission-computed tomography (PET-CT) has been used as a molecular level biomarker for the presence of metabolically active proinflammatory macrophages in rupture-prone early atherosclerotic plaques. We hypothesized that 18FDG PET-CT imaging would detect arterial inflammation and early atherosclerosis in HIV-infected adults with modest CVD risk.

Methods

We studied 9 HIV-infected participants with fully suppressed HIV viremia on antiretroviral therapy (8 men, median age 52 yrs, median BMI 29 kg/m2, median CD4 count 655 cells/μL, 33% current smokers) and 5 HIV-negative participants (4 men, median age 44 yrs, median BMI 25 kg/m2, no current smokers). Mean Framingham Risk Scores were higher for HIV-infected persons (9% vs. 2%, p < 0.01). 18FDG (370 MBq) was administered intravenously. 3D-PET-CT images were obtained 3.5 hrs later. 18FDG uptake into both carotid arteries and the aorta was compared between the two groups.

Results

Right and left carotid 18FDG uptake was greater (P < 0.03) in the HIV group (1.77 ±0.26, 1.33 ±0.09 target to background ratio (TBR)) than the control group (1.05 ± 0.10, 1.03 ± 0.05 TBR). 18FDG uptake in the aorta was greater in HIV (1.50 ±0.16 TBR) vs control group (1.24 ± 0.05 TBR), but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.18).

Conclusions

Carotid artery 18FDG PET-CT imaging detected differences in vascular inflammation and early atherosclerosis between HIV-infected adults with CVD risk factors and healthy HIV-seronegative controls. These findings confirm the utility of this molecular level imaging approach for detecting and quantifying glucose uptake into inflammatory macrophages present in metabolically active, rupture-prone atherosclerotic plaques in HIV infected adults; a population with increased CVD risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atherosclerosis is initiated by a series of proinflammatory events that occur in the arterial wall causing endothelial smooth muscle disruption, macrophage activation and infiltration, oxidized lipid accumulation, and plaque formation [1–6]. Several circulating and imaging biomarkers for these proatherogenic processes have been assessed clinically [7–14]. Unfortunately, few are specific for early molecular level events involved in atherogenesis. Thus, they are not predictive biomarkers of subclinical atherosclerosis that identify people at early risk for developing vascular plaques. Moreover, none of these biomarkers provides information about the risk for plaque rupture or thrombosis that result in infarct or stroke.

People living with human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) have a 2-fold greater risk for experiencing a stroke or myocardial infarction than the general population [15–17]. Evidence suggests that chronic low-grade inflammation associated with the host immune response to HIV infection and ongoing viral replication contributes to greater cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk and the higher incidence of CV events in HIV infected adults [18–23]. However, the evidence is based primarily on circulating biomarkers for inflammation (hsCRP, D-dimer, cytokines) which are neither sensitive, nor specific molecular-level predictive biomarkers for early proatherogenesis or vascular plaque in/stability [21, 24].

Several groups have pioneered the use of 18Fluoro-deoxyglucose (18FDG) uptake by proinflammatory macrophages present in the arterial wall as a non-invasive, sensitive, specific, and reproducible molecular level biomarker for early atheroma formation in metabolically active, rupture-prone atherosclerotic plaques [25–51]. Proinflammatory macrophages utilize glucose at a high rate [30, 40, 49], and 3-dimensional positron emission-computed tomography imaging (PET-CT) detects 18FDG uptake by macrophages in the vascular wall of animals and humans. 18FDG PET-CT imaging has been used to detect and quantify vascular inflammation in early atherogenesis and in vulnerable plaques in human aorta and carotid arteries, but not in people living with HIV and asymptomatic CVD.

The purpose of this proof-of-concept pilot study was to determine if 18FDG PET-CT imaging detects greater aortic and carotid inflammation and early atherosclerosis in HIV-infected adults with mild CVD risk and known carotid plaque than in healthy controls without significant CVD risk. If confirmed, 18FDG PET-CT can be used to monitor atherogenesis, determine the independent contributions of HIV infection and anti-retroviral therapy to vascular inflammation, and evaluate the anti-inflammatory, anti-atherogenic effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in people living with HIV.

Participants

Healthy men and women were recruited from Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences Research Participant Registry. Inclusion criteria were: 35–60 yrs old, confirmed HIV seronegative status, fasting plasma glucose <100 mg/dL and <140 mg/dL two hours after ingesting a 75-gr glucose beverage, fasting serum triglycerides <150 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol >40 mg/dL (men), >50 mg/dL(women), resting blood pressures <130/85 mmHg), carotid intima media thickness <0.8 mm and no evidence for carotid plaque, waist circumference (at the umbilicus) <102 cm (men, <88 cm (women). Exclusion criteria were: known cardiac or cerebrovascular disease, kidney or liver disease (active hepatitis B or C), certain medications (e.g., glucose- or lipid-lowering agents, anti-hypertensives, low dose aspirin, or other anti-inflammatory agents), illegal drug use (cocaine, methamphetamines, opiates detected on urine drug screen), pregnancy, cognitive impairment that limited their ability to provide voluntary informed consent, incarcerated or otherwise unable to provide informed consent. We excluded younger adults because the prevalence of atherosclerosis is rare in people <35 yrs old. Before screening, healthy controls were informed that participation required a test for HIV-infection and the implications of a positive HIV test.

HIV infected men and women were recruited from the Washington University AIDS Clinical Trials Unit and Infectious Diseases Clinics. Inclusion criteria were: 35–60 yrs old, documented HIV seropositive status, stable antiretroviral therapy for at least the past 4 months, CD4+ T-cell count >200 cells/μL, plasma HIV RNA <50 copies/mL, fasting plasma glucose 100–126 mg/dL, or 140–200 mg/dL two hours after ingesting 75-gr glucose beverage, or fasting triglycerides >150 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dL (men), <50 mg/dL (women), or resting blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, carotid intima media thickness >0.8 mm or evidence of carotid plaque, or waist circumference ≥102 cm(men), ≥88 cm(women), or BMI 25–35 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria were identical to those used for the healthy controls. By enrolling two groups with distinctly different cardiometabolic phenotypes, we optimized our chances of detecting a difference in arterial inflammation.

We enrolled 9 HIV infected adults with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and documented (ultrasound) carotid intima media thickening or non-obstructive plaque, and 5 HIV seronegative adults with no CVD risk factors (Table 1). Right and left carotid 18FDG PET-CT studies were conducted on all 14 participants. Aorta 18FDG PET-CT studies were added after the first five participants were enrolled, so aorta 18FDG studies were conducted on 4 controls and 5 HIV participants. All participants provided verbal and written informed consent. The informed consent document was approved by the Human Research Protection Office and the Radioactive Drug Research Committee at Washington University School of Medicine. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (#00958815).

Methods

Carotid ultrasound imaging

Carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) was measured by a single vascular sonographer using B-mode images of both carotid arteries expressed as the average thickness of the far walls of the right and left common carotid arteries; each site represents the average of 3 separate measurements [7]. The intra-class correlation coefficient for repeated measures of the CIMT is 0.91 at our laboratory [52]. The presence of carotid plaque was defined as described [7]; focal wall thickening that was ≥50% of the surrounding vessel wall or as a focal region with CIMT >1.5 mm that protruded into the lumen and was distinct from the adjacent boundary. Carotid wall thickening that did not meet this definition (<50% or <1.5 mm) was classified as a non-obstructive plaque.

18FDG PET-CT imaging

After an overnight fast, 18FDG (~370 MBq; 9.9 ± 0.5 mCi) was administered intravenously and 3.5 hr later, 3D-PET-CT images of the thoracic ascending, arch, and descending aorta and carotid arteries were obtained. Prior to 18FDG administration, fasting blood glucose concentration was measured; if >150 mg/dL the scan was rescheduled. To minimize motion artifact during image acquisition, each participant was individually fitted with a thermoplastic mask (Orfit Industries America, Jericho, NY) that was secured to the scanner table and immobilized their head, neck and shoulders.

A Biograph 40 Truepoint PET-CT scanner (Siemens, Malvern, PA) was used to acquire 3-dimensional neck and chest CT attenuation and contrast CT scans. The PET used lutetium oxyorthosilicate detectors (169 crystals/detector block, 192 detector blocks, 52 detector rings) and a 216 mm axial field of view (FOV). The CT has 40 detector rows and a 700 mm transaxial extended FOV. The CT attenuation scans used low dose CT (30 mAs (eff.), 120 kV, 0.5 sec rotation, 0.8 pitch, 28.8 mm collimation, 3 mm slice thickness, 500 mm transaxial FOV).

PET images were obtained at 2 bed positions (15 min per position) and both attenuation corrected and non-attenuation images were reconstructed in a 168 x 168 pixel matrix. Attenuation corrected PET images were reconstructed with ordered subset method of the expectation maximization (OSEM) using 4 iterations, 8 subsets and Gaussian filter 5 mm Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM). Only CT attenuated PET volumes were used for analysis. Contrast CT images were obtained immediately after the PET images were obtained. Contrast CT used 150 mAs (eff.), 120 kV, 0.5 sec rotation, 1.0 pitch, 28.8 mm collimation, 3 mm slice thickness, 500 mm transaxial FOV. Immediately prior to acquiring contrast CT images, 70 mL of Isovue-370 (Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) were infused intravenously. The contrast agent clearly delineated the narrow carotid arteries and jugular veins, and optimized CT and PET image co-registration and analysis.

PET-CT image analysis

Image analysis was conducted using custom extensions of MATLAB (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA). All images were analyzed by the same analyst (blinded to group assignment) using a standardized workflow. In general, MATLAB functions were used to co-register PET, CT attenuation and contrast CT images/datasets, quantify maximum 18FDG uptake (SUV) within the vessels from 1 cm above to 1 cm below the right and left carotid bifurcation, and through the ascending, arch, and descending aorta. Background 18FDG uptake in corresponding regions of the jugular veins and superior vena cava were used to calculate the maximum target-to-background ratio (TBRmax) in both carotid arteries and the aorta.

Specifically, PET volumes were converted to body weight standardized uptake values (SUVbw), where, 1 mL pure water = 1gr of body weight. In both regions of interest (neck, upper chest), axial PET and CT volumes were cropped to focus and reduce the dataset sizes. Within each axial image, rigid anatomical landmarks were identified (neck = cervical vertebrae; upper chest = sternum) and used to align the contrast CT volume with corresponding PET and CT attenuation volumes. Affine volume transformation by normalized cross correlation that allowed for rotation and shift in all three planes was used to register the contrast CT scan with the CT attenuation scan using the nearest rigid (bone) landmark corresponding to the vessel of interest. The contrast CT and CT attenuation co-registration matrix obtained was then used to align the corresponding PET volume. This provided optimal PET volume co-registration with contrast CT-enhanced vascular anatomy. MATLAB functions then quantified 18FDG SUV metrics (mean, median, standard deviation, min, max) along the arterial and venous regions, and these were used to derive carotid and aorta TBRmax[28].

Serum lipids and lipoproteins

Blood was collected from an antecubital vein after a 10-12 hr overnight fast. As described [53], serum triglycerides, total- and HDL-cholesterol were measured and LDL-cholesterol estimated in the Core Laboratory for Clinical Studies at Washington University Medical Center. The accuracy of these methods is verified and standardized by participation in the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Lipid Standardization Program, the CDC Cholesterol Reference Method Laboratory Network, and the College of American Pathologists external proficiency program [54]. Framingham 10-yr coronary heart disease (CHD) risk was determined using an American Heart Association calculator (http://hp2010.nhlbihin.net/atpiii/calculator.asp?usertype=prof).

Blood hormones and metabolites

As described [55], plasma glucose concentration was quantified using an automated YSI glucose analyzer (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH), and plasma insulin and C-peptide concentrations were determined using chemiluminescent immunometric methods (Immulite; Siemens, Los Angeles, CA). The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA) was calculated as described [56].

Systemic inflammatory biomarkers

D-dimer and highly sensitive C-Reactive Protein (hsCRP) concentrations were quantified using particle enhanced immuno-turbidimetric assay kits according to manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Human plasma CRP and D-dimer complex with latex particles coated with a monoclonal antibody directed against CRP or D-dimer epitopes, and the precipitate was assayed for turbidity on a Roche/Hitachi Cobas c system. Adequate amounts of archived plasma from 4 healthy controls and 5 HIV participants were available for these assays.

Data analysis

Mean ± standard error (SE), median, minimum and maximum values are reported for the participant characteristics. Physical and demographic characteristics were compared using a non-parametric Fishers’ exact test or Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks test. Carotid and aorta maximum TBRmax were compared between groups using an unpaired t-test. P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

The two groups had similar demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity; Table 1). Mean and median age for HIV + participants (Mean ± SE; 52 ± 3 yrs, median = 52 yrs) were numerically, but not statistically higher (p = 0.07) than controls (44 ± 3 yrs, median =46 yrs). Immune (CD4+ T-cell count = 771 ± 132 cells/μL) and virologic (all <50 copies HIV RNA/mL) status were stable and controlled in the HIV + participants. By design, cardiovascular disease risk profiles were worse among HIV + participants than controls (Table 1). The Framingham 10-yr coronary heart disease (CHD) risk score was greater (9 ± 2%) in HIV + participants than in controls (2 ± 1%; p < 0.01), but by definition these represent low (<10%) risk for CHD events (MI, stroke). Four of the 9 HIV participants had Framingham 10-yr CHD risk scores between 10-20%. The higher CHD risk score among HIV + participants was attributed to current tobacco use and higher systolic blood pressure (history of hypertension).

The mean intima media thickness of the common carotid arteries was greater (p < 0.01) in HIV + participants (0.78 ± 0.02 mm) than controls (0.54 ± 0.03 mm), and eight of nine HIV + participants had ultrasound detectable non-obstructive plaques in at least one carotid artery, while no plaques were detected in controls. Glycemic control parameters (fasting glucose, insulin, C-peptide, HOMA) were not different between control and HIV + participants. Fasting triglycerides were greater (p = 0.04) in HIV + participants (149 ±35 mg/dL) than controls (63 ± 6 mg/dL), but total-, HDL-, and calculated LDL-cholesterol levels were not different between groups. D-dimer and hsCRP levels were numerically, but not statistically (P > 0.16), higher in HIV + participants than controls.

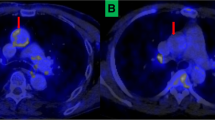

Representative images of carotid 18FDG PET uptake superimposed on the contrast CT images, and the corresponding carotid ultrasound images are provided for an HIV + and a control participant (Figure 1). Right and left carotid 18FDG uptake (TBRmax) was greater (P < 0.03) in HIV + participants (1.77 ±0.26, 1.33 ±0.09) than controls (1.05 ± 0.10, 1.03 ± 0.05; Figure 2). Aorta 18FDG TBRmax tended (P = 0.18) to be greater in HIV + participants (1.50 ± 0.16) than controls (1.24 ±0.05; Figure 2).

Representative co-registered 3-dimensional positron emission (PET) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) images of the right carotid artery of a healthy HIV-seronegative control male (Panel 1), and an HIV infected man with CVD risk factors (Panel 2). Transverse, sagittal, and coronal contrast CT images (A) and PET 18FDG uptake images (B) along with the corresponding carotid ultrasound images for these two men are shown. The anterior wall of the right carotid artery (upper portion of the carotid ultrasound image) is indicated with a yellow arrow and the posterior wall with a red arrow (lower portion of the image). In the HIV infected man (Panel 2), ultrasound imaging detected increased carotid artery intima media thickness in both the anterior and posterior walls and a non-obstructive plaque in the posterior wall of the right carotid artery. In the healthy control male (Panel 1), the intima media thickness was normal and no plaques were present in the anterior or posterior walls of the right carotid artery. Carotid PET imaging detected regions of higher 18FDG uptake (red nodules in blue, red and green ovals) in the HIV infected man (Panel 2B), while less 18FDG uptake was detected in the carotid artery of the healthy control male (Panel 1B).

Right and left carotid18FDG uptake (Mean ± SE) was greater ( P < 0.03) in the HIV group (n = 9; 1.77 ± 0.26, 1.33 ± 0.09 target to background ratio-max (TBR max )) than in the control group (n = 5; 1.05 ± 0.10, 1.03 ±0.05 TBR max ). Aorta 18FDG uptake tended (P = 0.18) to be greater in HIV (n = 5; 1.50 ±0.16 TBRmax) vs control group (n = 4; 1.24 ±0.05 TBRmax).

Discussion

Carotid artery 18FDG PET-CT imaging detected differences in vascular inflammation and early atherosclerosis between HIV-infected adults with CVD risk factors and healthy HIV-seronegative controls. These findings confirm the utility of this molecular level imaging approach for detecting and quantifying glucose uptake into inflammatory macrophages present in metabolically active, rupture-prone atherosclerotic lesions or early non-obstructive plaques in HIV infected adults; a population with increased CVD risk.

Vascular inflammation has been implicated in the underlying pathophysiology for the higher incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke in HIV infected adults taking anti-retroviral medications. However, this suggestion is based on indirect, non-specific measures of circulating pro-inflammatory or pro-oxidant stress biomarkers, or static vascular imaging methods (carotid intima media thickness, coronary calcium deposition). We provide the first direct, molecular-level evidence for the presence of metabolically active, inflammatory vascular lesions/plaques in people living with HIV infection. It is important to note that the HIV participants studied had modest clinical evidence of CVD risk; characterized by carotid intima media thickening or small non-obstructive plaques and low Framingham 10-yr CHD risk profiles (9 ± 2% risk). However, carotid 18FDG PET-CT imaging and greater TBRmax provided clearer evidence of atherosclerotic vascular disease in HIV + participants.

We specifically selected participants with ultrasound-detected carotid intima media thickening and non-obstructive plaques in order to assess the ability of vascular 18FDG PET-CT imaging to detect an expected difference in vascular inflammation between healthy controls and HIV-infected men and women with CHD risk. In agreement with others, we found that not all calcified lesions are metabolically active, inflammatory, rupture-prone plaques [25, 26]. The current study was underpowered to definitively assess the relationship between 18FDG uptake and carotid thickness. The relationship between plaque morphology and 18FDG uptake should be further investigated in future studies.

This imaging method may be useful for addressing several critically important clinical questions in HIV infected people, e.g., Is there vascular inflammation in untreated HIV-infection? Does highly active anti-retroviral therapy reduce or worsen vascular inflammation? Is vascular inflammation worse in older HIV-infected adults than in age- and CVD risk factor-matched HIV-seronegative adults? Do effective treatments for insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, or anti-inflammatory agents reduce vascular inflammation in HIV? In the long-term, does a reduction in vascular inflammation translate to fewer clinical events (stroke, MI) in HIV? This non-invasive method is ideal for examining interactions among vascular inflammation and CVD risk factors (insulin resistance, central obesity, dyslipidemia) on early atherosclerotic progression in HIV and other autoimmune disorders where inflammatory stimuli are implicated (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease).

Circulating inflammatory biomarker levels (hsCRP, D-dimer) were variable, but on average, were 3–4 times higher in HIV than healthy controls. This supports the generalization that even well-controlled HIV (using contemporary anti-viral agents) is associated with a chronic, low-grade, pro-inflammatory state, but the stimulus, source, location and severity of the inflammation cannot be discerned from these plasma biomarkers. HIV related inflammation can be caused by multiple factors, including chronic replicating virus, anti-HIV medications, gut microbial translocation, obesity, diabetes, tobacco/alcohol/illegal drug abuse, hepatitis co-infection, or other co-morbidities. 18FDG PET-CT specifically revealed vascular inflammation in the carotid arteries as a quantifiable source for molecular-level, pro-inflammatory events that are biochemically related to early atherogenesis, and if left unrestrained, can precipitate a CV event.

This study has limitations. We had a small sample size and we may have been underpowered to detect certain between group differences. But, these are expensive imaging studies, and therefore we intended these data to show proof-of-principle for larger clinical studies. On average, the HIV infected adults tended to be older than the healthy controls. Advanced age is associated with more vascular inflammation and 18FDG uptake. But, the focus of this study was not on “what causes vascular inflammation in HIV?” Instead, the focus was on a dichotomous outcome; i.e., can we detect vascular inflammation using 18FDG uptake in HIV with mild CVD risk? The intent was not to address the question “is vascular inflammation worse in age-matched HIV vs healthy controls?” This is an excellent follow-up study, now that we have developed the technique and we understand the usefulness of 18FDG PET-CT imaging for detecting early, low-level vascular inflammation in people living with HIV. We did not attempt to quantify 18FDG uptake in the coronary vessels; these are very narrow, in motion, and surrounded by the glucose-consuming heart muscle. Attempts to image inflammation in the coronary vessels using 18FDG have been made [57]. We cannot determine the specific risk factor that caused greater 18FDG uptake in HIV participants (e.g., tobacco use, hypertension, glycemic control, higher triglycerides) because the two groups were selected based on their distinctly different cardiometabolic phenotypes. Likewise, the study was not designed to determine whether HIV-infection per se, or which specific anti-HIV medication caused greater 18FDG uptake in the HIV + participants. However, these pathogenesis questions can be addressed given the proof-of-principle findings reported here. Indeed, recent studies have begun to investigate these questions using 18FDG PET-CT [58].

Conclusion

Carotid 18FDG PET-CT imaging detected significant vascular inflammation in HIV- infected men and women with low Framingham CHD risk scores, suggesting that this molecular imaging method is sensitive to early pro-atherosclerotic processes in a clinical population suspected of having chronic, low-grade inflammation-induced cardiovascular disease.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three dimensional

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CIMT:

-

Carotid intima media thickness

- cm:

-

centimeters

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- eff:

-

Effective

- 18FDG:

-

18Fluoro deoxy-glucose

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- FWHM:

-

Full width half maximum

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HOMA:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- hr:

-

hours

- hsCRP:

-

Highly sensitive c-reactive protein

- kg:

-

kilograms

- kV:

-

kilovolts

- m:

-

meters

- mAs:

-

milliamperes

- MBq:

-

megabecquerel

- mCi:

-

milliCuries

- mg/dL:

-

milligrams per deciliter

- μg FEU/mL:

-

Micrograms of human fibrinogen equivalent units per milliliter

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- min:

-

minutes

- mL:

-

milliliters

- μL:

-

microliters

- mm:

-

millimeters

- mmHg:

-

millimeters mercury

- μU/mL:

-

microUnits per milliliter

- ng/mL:

-

nanograms per milliliter

- OSEM:

-

Ordered subset method of the expectation maximization

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- SE:

-

Standard error

- sec:

-

seconds

- SUV:

-

Standard uptake value

- TBR:

-

Target to background ratio

- yrs:

-

years.

References

Ross R: Atherosclerosis – an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 115-126. 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207.

Ibañez B, Badimon JJ, Garcia MJ: Diagnosis of atherosclerosis by imaging. Am J Med. 2009, 122: S15-S25. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.10.014.

Liang C-P, Han S, Senokuchi T, Tall AR: The macrophage at the crossroads of insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2007, 100: 1546-1555. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152165.

Rader DJ, Puré E: Lipoproteins, macrophage function, and atherosclerosis: Beyond the foam cell?. Cell Metab. 2005, 1: 223-230. 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.005.

Tabas I, Tall A, Accili D: The impact of macrophage insulin resistance on advanced atherosclerotic plaque progression. Circ Res. 2010, 106: 58-67. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208488.

Andersson J, Libby P, Hansson GK: Adaptive immunity and atherosclerosis. Clin Immunol. 2010, 134: 33-46. 10.1016/j.clim.2009.07.002.

Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, Najjar SS, Rembold CM, Post WS: Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008, 21: 93-111. 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.011.

Poredos P: Intima-media thickness: indicator of cardiovascular risk and measure of the extent of atherosclerosis. Vasc Med. 2004, 9: 46-54. 10.1191/1358863x04vm514ra.

Papadopoulou C, Corrigall V, Taylor PR, Poston RN: The role of the chemokines MCP-1, GRO-a, IL-8 and their receptors in the adhesion of monocytic cells to human atherosclerotic plaques. Cytokine. 2008, 43: 181-186. 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.05.009.

O'Byrne D, Devaraj S, Islam KN, Collazo R, McDonald L, Grundy S, Jialal I: Low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-induced monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion, soluble cell adhesion molecules, and autoantibodies to oxidized-LDL in chronic renal failure patients on dialysis therapy. Metabolism. 2001, 50: 207-215. 10.1053/meta.2001.19486.

Morrow JD: Quantification of isoprostanes as indices of oxidant stress and the risk of atherosclerosis in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005, 25: 279-286.

McNeely MJ, McClelland RL, Bild DE, Jacobs DR, Tracy RP, Cushman M, Goff DC, Astor BC, Shea S, Siscovick DS: The association between A1C and subclinical cardiovascular disease. Diab Care. 2009, 32: 1727-1733. 10.2337/dc09-0074.

Masiá M, Bernal E, Padilla S, Graells ML, Jarrín I, Almenar MV, Molina J, Hernández I, Gutiérrez F: The role of C-reactive protein as a marker for cardiovascular risk associated with antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients. Atherosclerosis. 2007, 195: 167-171. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.013.

Koenig W, Khuseyinova N: Biomarkers of atherosclerotic plaque instability and rupture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007, 27: 15-26. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251503.35795.4f.

Kaplan RC, Tien PC, Lazar J, Zangerle R, Sarcletti M, Pollack TM, Rind DM, Sabin C, Friis-Moller N, Lundgren JD: Antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357: 715-717.

Kingsley LA, Cuervo-Rojasc J, Muñoz A, Palella FJ, Post W, Witt MD, Budoff M, Kuller L: Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis, HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS. 2008, 22: 1589-1599. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328306a6c5.

Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK: Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92: 2506-2512. 10.1210/jc.2006-2190.

Baker JV, Henry WK, Neaton JD: The consequences of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy use for cardiovascular disease risk: shifting paradigms. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009, 4: 176-182. 10.1097/COH.0b013e328329c62f.

Carr A, Ory D: Does HIV cause cardiovascular disease?. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e496-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030496.

Martinez E, Visnegarwala F, Grund B, Thomas A, Gibert C, Shlay J, Drummond F, Pearce D, Edwards S, Reiss P: The effects of intermittent, CD4-guided antiretroviral therapy on body composition and metabolic parameters. AIDS. 2010, 24: 353-363. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283333666.

Phillips AN, Carr A, Neuhaus J, Visnegarwala F, Prineas R, Burman WJ, Williams I, Drummond F, Duprez D, Belloso WH: Interruption of antiretroviral therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease in persons with HIV-1 infection: exploratory analyses from the SMART trial. Antivir Ther. 2008, 13: 177-187.

Stein JH: Cardiovascular risks of antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 1773-1775. 10.1056/NEJMe078037.

El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, Gordin F, Abrams D, Arduino RC, Babiker A, Burman W, Clumeck N, The Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy Study Group: CD4+ Count-Guided Interruption of Antiretroviral Treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 2283-2296.

Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, Wit SD, Drummond F, Lane HC, Ledergerber B, Lundgren J, Neuhaus J, Nixon D: Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 2008, 5: e203-10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203.

Aziz K, Berger K, Claycombe K, Huang R, Patel R, Abela GS: Noninvasive detection and localization of vulnerable plaque and arterial thrombosis with computed tomography angiography/positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2008, 117: 2061-2070. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652313.

Bural GG, Torigian DA, Botvinick E, Houseni M, Basu S, Chen W, Alavi A: A pilot study of changes in 18 F-FDG uptake, calcification and global metabolic activity of the aorta with aging. Hell J Nucl Med. 2009, 12: 123-128.

Davies JR, Rudd JHF, Fryer TD, Graves MJ, Clark JC, Kirkpatrick PJ, Gillard JH, Warburton EA, Weissberg PL: Identification of culprit lesions after transient ischemic attack by combined 18 F Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2005, 36: 2642-2647. 10.1161/01.STR.0000190896.67743.b1.

Graebe M, Borgwardt L, Højgaard L, Sillesen H, Kjaer A: When to image carotid plaque inflammation with FDG PET/CT. Nucl Med Comm. 2010, 31: 773-779. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32833c365e.

Hoh CK: Clinical use of FDG PET. Nucl Med Biol. 2007, 34: 737-742. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.07.001.

Hongming Z, Abass A: 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic imaging in the detection and monitoring of infection and inflammation. Semin Nucl Med. 2002, 32: 47-59. 10.1053/snuc.2002.29278.

Izquierdo-Garcia D, Davies JR, Graves MJ, Rudd JHF, Gillard JH, Weissberg PL, Fryer TD, Warburton EA: Comparison of methods for magnetic resonance-guided [18-F]luorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in human carotid arteries: reproducibility, partial volume correction, and correlation between methods. Stroke. 2009, 40: 86-93. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521393.

Kai H: Novel non-invasive approach for visualizing inflamed atherosclerotic plaques using fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010, 10: 1-8. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00564.x.

Kim TN, Kim S, Yang SJ, Yoo HJ, Seo JA, Kim SG, Kim NH, Baik SH, Choi DS, Choi KM: Vascular inflammation in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes: analysis with18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010, 3: 142-148. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.888909.

Moustafa RR, Izquierdo D, Weissberg PL, Baron JC, Warburton EA: Identifying aortic plaque inflammation as a potential cause of stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008, 79: 236-10.1136/jnnp.2007.123232.

Moustafa RR, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Fryer TD, Graves MJ, Rudd JHF, Gillard JH, Weissberg PL, Baron J-C, Warburton EA: Carotid plaque inflammation is associated with cerebral microembolism in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke: a pilot study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010, 3: 536-541. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.938225.

Okane K, Ibaraki M, Toyoshima H, Sugawara S, Takahashi K, Miura S, Shimosegawa E, Satomi J, Kitamura K, Satoh T: 18 F-FDG accumulation in atherosclerosis: use of CT and MR co-registration of thoracic and carotid arteries. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006, 33: 589-594. 10.1007/s00259-005-0005-2.

Rudd JHF, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Rafique A, Farkouh M, Fuster V, Fayad ZA: 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation is highly reproducible: implications for atherosclerosis therapy trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 50: 892-896. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.024.

Rudd JHF, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Woodward M, Fuster V, Farkouh ME, Fayad ZA: Relationships among regional arterial inflammation, calcification, risk factors, and biomarkers: a prospective fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computed tomography imaging study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009, 2: 107-115. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.811752.

Rudd JHF, Narula J, Strauss HW, Virmani R, Machac J, Klimas M, Tahara N, Fuster V, Warburton EA, Fayad ZA, Tawakol AA: Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation by fluorodeoxyglucose with positron emission tomography: ready for prime time?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55: 2527-2535. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.061.

Rudd JHF, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, Jones HA, Clark JC, Antoun N, Johnstrom P, Davenport AP, Kirkpatrick PJ, Arch BN: Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18 F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002, 105: 2708-2711. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000020548.60110.76.

Subramanian S, Tawakol A: Molecular PET and CT imaging of inflammation and metabolism in atherosclerosis. Curr Cardiovasc Imag Rep. 2010, 3: 92-98. 10.1007/s12410-010-9014-z.

Tahara N, Kai H, Ishibashi M, Nakaura H, Kaida H, Baba K, Hayabuchi N, Imaizumi T: Simvastatin attenuates plaque inflammation: evaluation by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 48: 1825-1831. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.069.

Tahara N, Kai H, Nakaura H, Mizoguchi M, Ishibashi M, Kaida H, Baba K, Hayabuchi N, Imaizumi T: The prevalence of inflammation in carotid atherosclerosis: analysis with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Eur Heart J. 2007, 28: 2243-2248. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm245.

Tahara N, Kai H, Yamagishi S-i, Mizoguchi M, Nakaura H, Ishibashi M, Kaida H, Baba K, Hayabuchi N, Imaizumi T: Vascular inflammation evaluated by [18 F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is associated with the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 49: 1533-1539. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.046.

Tatsumi M, Cohade C, Nakamoto Y, Wahl RL: Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the aortic wall at PET/CT: possible finding for active atherosclerosis. Radiology. 2003, 229: 831-837. 10.1148/radiol.2293021168.

Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, Bedri S, Vermylen D, Cury RC, Yates D, LaMuraglia GM, Furie K, Houser S: In vivo 18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 48: 1818-1824. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.076.

Wassélius J, Larsson S, Jacobsson H: Time-to-time correlation of high-risk atherosclerotic lesions identified with [18 F]-FDG-PET/CT. Ann Nucl Med. 2009, 23: 59-64. 10.1007/s12149-008-0207-3.

Fox JJ, Strauss HW: One step closer to imaging vulnerable plaque in the coronary arteries. J Nucl Med. 2009, 50: 497-500. 10.2967/jnumed.108.056325.

Joshi F, Rosenbaum D, Bordes S, Rudd JHF: Vascular imaging with positron emission tomography. J Intern Med. 2011, 270: 99-109. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02392.x.

Duivenvoorden R, Fayad Z: Utility of atherosclerosis imaging in the evaluation of high-density lipoprotein-raising therapies. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2011, 13: 277-284. 10.1007/s11883-011-0176-1.

Owen DRJ, Lindsay AC, Choudhury RP, Fayad ZA: Imaging of atherosclerosis. Ann Rev Med. 2011, 62: 25-40. 10.1146/annurev-med-041709-133809.

de las Fuentes L, Waggoner AD, Mohammed BS, Stein RI, Miller Iii BV, Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Klein S, Davila-Roman VG: Effect of moderate diet-induced weight loss and weight regain on cardiovascular structure and function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54: 2376-2381. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.054.

Yarasheski KE, Tebas P, Claxton S, Marin D, Coleman T, Powderly WG, Semenkovich CF: Visceral adiposity, C-peptide levels, and low lipase activities predict HIV-dyslipidemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 285: E899-E905.

Standardization of lipid and lipoprotein measurements. . Edited by: Myers GL, Cooper GR, Henderson LO, Hassemer DJ, Kimberly MM. 1997, AACC, Washington, DC, 223-250.

Yarasheski KE, Cade WT, Overton ET, Mondy KE, Hubert S, Laciny E, Bopp C, Lassa-Claxton S, Reeds DN: Exercise training augments the peripheral insulin sensitizing effects of pioglitazone in HIV-infected adults with insulin resistance and central adiposity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 300: E243-E251. 10.1152/ajpendo.00468.2010.

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudneski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC: Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and ß-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985, 28: 412-419. 10.1007/BF00280883.

Wykrzykowska J, Lehman S, Williams G, Parker JA, Palmer MR, Varkey S, Kolodny G, Laham R: Imaging of inflamed and vulnerable plaque in coronary arteries with 18 F-FDG PET/CT in patients with suppression of myocardial uptake using a low-carbohydrate, high-fat preparation. J Nucl Med. 2009, 50: 563-568. 10.2967/jnumed.108.055616.

Subramanian S, Tawakol A, Burdo T, Abbara S, Wei J, Zanni M, Hoffmann U, Williams K, Lo J, Grinspoon S: Increased arterial inflammation in association with monocyte activation in HIV + patients (abstract # 121). 19thConference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 2012, , Seattle, WA, 124-

Acknowledgements

Kitty Krupp, RN provided nursing support in the PET suite. Joann L. Reagan, RN, RVT and Sharon L. Heuerman, RN provided support in the Cardiovascular Imaging and Clinical Research Core Laboratory. This publication was made possible by Grant # UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and NIH grants R01 DK049393 (KEY) and P60 DK020579 (Diabetes Research Training Center). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KEY conceived, designed, and coordinated the study, acquired and interpreted data, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. EL participated in the design and coordination of the study, and acquired data. ETO and DNR participated in the design and coordination of the study, acquired and interpreted data, monitored participants, and helped draft the manuscript. MH and SB participated in the design and coordination of the study, acquired PET-CT images, assisted with PET-CT image analysis, and helped draft the manuscript. VGD-R participated in the design and conduct of the study, acquired, analyzed, interpreted carotid ultrasound images, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yarasheski, K.E., Laciny, E., Overton, E.T. et al. 18FDG PET-CT imaging detects arterial inflammation and early atherosclerosis in HIV-infected adults with cardiovascular disease risk factors. J Inflamm 9, 26 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-9255-9-26

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-9255-9-26