Abstract

Background

In an effort to identify new alternatives for long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC n-3 PUFA) supplementation, the effect of three sources of omega 3 fatty acids (algae, fish and Echium oils) on lipid profile and inflammation biomarkers was evaluated in LDL receptor knockout mice.

Methods

The animals received a high fat diet and were supplemented by gavage with an emulsion containing water (CON), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 42.89%) from algae oil (ALG), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 19.97%) plus DHA (11.51%) from fish oil (FIS), and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, 26.75%) plus stearidonic acid (SDA, 11.13%) from Echium oil (ECH) for 4 weeks.

Results

Animals supplemented with Echium oil presented lower cholesterol total and triacylglycerol concentrations than control group (CON) and lower VLDL than all of the other groups, constituting the best lipoprotein profile observed in our study. Moreover, the Echium oil attenuated the hepatic steatosis caused by the high fat diet. However, in contrast to the marine oils, Echium oil did not affect the levels of transcription factors involved in lipid metabolism, such as Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor α (PPAR α) and Liver X Receptor α (LXR α), suggesting that it exerts its beneficial effects by a mechanism other than those observed to EPA and DHA. Echium oil also reduced N-6/N-3 FA ratio in hepatic tissue, which can have been responsible for the attenuation of steatosis hepatic observed in ECH group. None of the supplemented oils reduced the inflammation biomarkers.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that Echium oil represents an alternative as natural ingredient to be applied in functional foods to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increased intake of omega-6 fatty acids during the 20th century as a result of an elevation in vegetal oil consumption (of more than 1,000-fold) contributed to a decline in the tissue concentration of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC n-3 PUFA) [1, 2], which might be associated with the increased incidence of inflammatory disorders, such as atherosclerosis [3]. The development of atherosclerotic plaques is associated with several clinical cardiovascular events. Considering the health effects of LC n-3 PUFA toward the reduction of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [4, 5], many industries have added eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) from marine oils to food formulations or supplements, aiming to explore this health claim. In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) qualified the health claim of products containing EPA and DHA [6]. A similar recommendation was also provided by the American Heart Association (AHA), who suggested consumption of 1 g/day of EPA + DHA for patients with CVD and 2–4 g/day for patients with hypertriglyceridaemia [7].

The cardioprotective effects of LC N-3 PUFA appear to be due to a synergism between multiple mechanisms including triacylglycerol (TG) lowering, improving membrane fluidity, anti-inflammatory, antiarrhythmic and antithrombotic effects [5]. The scientific evidence concerning the beneficial effects of the LC N-3 PUFA on lipid profile and inflammation were obtained from several studies using animal and human models. However, these effects and the mechanisms by which they occur are restricted to the action of EPA and DHA [8]. Other non-marine sources of omega 3 fatty acids (N-3 FA), such as alpha- linolenic acid (ALA) or stearidonic acid (SDA), can be converted in vivo to EPA and DHA by the desaturase and elongase enzymes in a tissue-dependent manner, the liver being the major site of this conversion [9]. It has been reported that the conversion rate of ALA is low (5-10% for EPA and < 1% for DHA), which diminishes the efficacy of these alternative sources in the reduction of cardiovascular risk [10–12]. However, due to dietary preferences, safety, sustainability, cost and oxidative stability aspects, other non-marine oils alternatives must be evaluated [3, 9–11, 13, 14]. It has been suggested that the low rate by which ALA is converted to EPA is a result of the limited activity of Δ6-desaturase when linoleic acid (LNA) is also present [15]. However SDA, a precursor of EPA that is found in plants, such as Echium (Echium plantagineum), black currant seed and other genetically modified seeds, does not need Δ6-desaturase activity to be converted into EPA [3, 10]. In an effort to identify new alternatives for LC N-3 PUFA supplementation, the objective of this study was to compare the effects of three sources of N-3 FA (algae, fish and Echium oil) on lipid composition and some inflammatory biomarkers using LDL receptor deficient mice (LDLr knockout mice) as model.

Methods

Oils and reagents

The N-3 FA used in this study were commercial products: the algae oil containing 40% DHA (DHASCO) was obtained from Martek Biosciences® (Winchester, KY, USA), the fish oil (EPA1T1600 MEG-3™) containing EPA (20%) + DHA (12%) was obtained from Ocean Nutrition® (Dartmouth, NS, Canada) and the Echium oil containing 11.5% SDA (AW39144ECH) was obtained from Oil Seed Extraction® (Ashburton, New Zealand). All reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Calbiochem Technology Inc. (Boston, MA, USA) and GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, Bucks, UK). The aqueous solutions were prepared with ultra-pure Milli-Q water (Millipore Ind. Com. Ltd., SP, Brazil), and the organic solvents were of HPLC grade. Fatty acids profile of the oils used in this study was analyzed by gas chromatography and is shown in Table 1.

Animals and diets

Forty male homozygous LDL receptor-deficient mice (LDLr Knockout mice, C57BL/6) weighing 25–29 g (4.0-4.5 months of age) were purchased from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences (São Paulo, Brazil). The mice were housed in plastic cages (5 animals/cage) at constant temperature (22 ± 2°C) and relative humidity (55 ± 10%), with a 12-h light–dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum, and animals were divided into four groups. All groups were fed with a high fat diet for 4 weeks (Table 2), and were supplemented with an oil-in-water emulsion (190 – 240 μL/d) per mouse containing fish oil (FIS), algae oil (ALG), Echium oil (ECH) or water (CON) by gavage. Amount of EPA, DHA, SDA and ALA ingested from added oil per day is presented in Table 3. We opted to compare the effect of the same amount of EPA+DHA in all groups. To achieve this objective the rate of conversion from SDA to EPA (4:1) proposed by Whelan [16] was adopted in our study. By this way, the EPA+DHA dosage applied was 0.7, 0.8 and 0.7 mg/day using Fish, Alagae and Echium oil respectively (Table 3). The emulsions were prepared weekly by mixing the respective oil with water using a high-pressure homogenizer (Homolab mod A-10, Alitec, São Paulo, Brazil). The emulsions were prepared in less than 2 minutes, and the temperature was kept below 40°C, during this short time. After, the emulsions were transferred to 2 mL eppendorf tubes, immediately immersed in nitrogen and kept at -80°C until the time of gavage. All this procedure was repeated twice a week. Emulsion characteristics are presented in Table 3. Diet consumption was measured daily and animals were weighed individually twice a week. After 4 weeks, the mice were fasted for 12 h, and anaesthetised with a mixture containing xylazine 2% (Sespo Ind. e Com. Ltda., Paulínia, Brazil), ketamine (Syntec do Brasil Ltda., Cotia, Brazil) and acepromazine (Vetnil Ind. e Com. de Prod. Veterinários Ltda., Louveira, Brazil). Blood samples collected from the brachial plexus were immediately centrifuged (1,600 × g for 15 min at 4°C), frozen under liquid nitrogen and stored (-80°C) for further analysis. The liver was excised, dried with lint and weighed. Small pieces of the larger lobe were frozen for Western blotting and further analysis, and a piece of the smaller lobe was immersed in 10% buffered formalin solution for histopathological examination. Subsequently, the animals were perfused with a cold NaCl solution (0.9%, 240.0 mL) via their left ventricle to remove the excess of blood. The animal protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Studies of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences (São Paulo, Brazil).

Measurements

Fatty acids were isolated from the liver and diets using the extraction methodology proposed by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (method 996.06) [17]. The fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) were suspended in hexane and analyzed by a gas chromatograph (GC17A Shimadzu Class CG, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a 30 m × 0.25 mm (i.d.), 0.25 μm film thickness fused silica capillary column (Supelcowax, Bellefont, PA, USA) and a flame ionization detector. Helium was used as a carrier gas, and the fatty acids were separated using a 10°C/min gradient from 80 to 150°C and then a 6°C/min gradient from 150°C to 230°C. Standard mixtures with 37 FAME and PUFA 3 methyl esters from Menhaden oil (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to identify the peaks. The results were expressed as percentage of the total fatty acids present.

The serum lipoprotein concentrations, including total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) and TG, were quantified using an enzymatic colorimetric test from Labtest (Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil). The low density lipoprotein levels (LDL) and VLDL were estimated using the Friedewald formula [18]. The inflammation biomarkers (C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin–6 (IL-6) vascular cell-adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM), Inter-Cellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM) and adiponectin) were analysed in serum samples using Multiplex commercial Kits (Millipore, St. Charles, MO, USA).

Liver histology

The representative liver fragments were fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution for approximately 48 hours. Then, the fragments were fixed in paraffin. The material was submitted to microtomy with a cut of 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological evaluation [19].

Western blotting analysis of hepatic peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α (PPARα) and liver X receptor α (LXRα)

The total nuclear protein was extracted from the frozen liver tissue samples using the specific commercial Kit NEPER (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Bucks, UK). Subsequently, 15 μg of the proteins present in the supernatant was separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to Amersham™ Hybond™-ECL™ nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare UK Ltd.-Amershan Place, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) using a humid system composed of buffer containing 25 mM Tris base, 192.0 mM glycine, 0.02% SDS, and 10% methanol (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Bucks, UK). The membranes were then blocked with 5% ECL advance blocking agent in TBST (Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20) for 1.5 h to prevent the occurrence of nonspecific binding, and they were incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit polyclonal to LXRα – ab 82774 and rabbit polyclonal to PPARα – ab 8934, ABCAM plc., Cambridge, MA, USA) diluted in a ratio of 1:345 and 1:500, respectively. After this step, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Bucks, UK). Following three washes in TBST, the immunoreactive bands were visualised using the ECL advance detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). To standardise the immunoblots, a digital detection system was applied (IMAGE QUANTTM 400 version 1.0.0, Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) using proliferating cell nuclear antigen – PCNA (ABCAM plc., Cambridge, MA, USA) as standard. The densitometry was quantified using the Discovery series™ Quantity one® Analysis Software version 4.6.3 (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The effect of each N-3 FA source on biomarkers was compared by one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD test. Equivalent non-parametric ANOVA was applied when there was no homogeneity of variances (Hartley test). A probability value of 0.05 was adopted to reject the null hypothesis. All calculations and graphs were performed using the software Statistica v.9 (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, USA).

Results

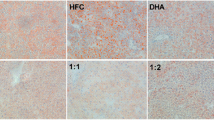

All groups showed the same weight gain and diet consumption (Table 4). Animals supplemented with Echium oil presented lower total cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations than Control, and lower VLDL than all of the other groups, constituting the best lipoprotein profile observed in this study. None of the N-3 FA sources altered any of the inflammation biomarkers (Table 4). The effect of N-3 FA associated with high fat diet on the histological evaluation of the liver tissue is presented in Figure 1. Hepatic steatosis can be observed in the CON group with fatty infiltration around the portal space. Fish and Echium oils attenuated hepatic steatosis, whereas algae oil did not promote any protection against the hepatic steatosis induced by the high fat diet. The N-3 FA must be present in liver to exert their effects on lipid metabolism. Of the main N-3 FA applied in our study (ALA, SDA, EPA and DHA) (Figure 2), only EPA was observed in a higher concentration in the liver homogenate of animals supplemented with fish and Echium oils (Table 5). Moreover, a lower omega 6/ omega 3 ratio (N-6/N-3 FA ratio) (p<0.001) was observed in liver of animals supplemented with Echium oil (Table 5). In order to better investigate the action of N-3 FA on the hepatic steatosis, two transcription factors involved in lipid metabolism were evaluated. Figures 3 and 4 present the influence of the N-3 FA supplementation on the hepatic transcription factors LXRα and PPARα, which are associated with fatty acids synthesis and oxidation, respectively. Animals supplemented with algae oil experienced a significant increase of PPARα expression when compared to all other groups (Figure 3). A decrease in LXRα expression was observed in the groups supplemented with fish and algae oils (Figure 4), whereas Echium oil did not alter any of these two transcription factors.

Representative photomicrographs of liver sections: (CON) - fatty infiltration around the portal space; (FIS) and (ECH) - antisteatogenic effect exhibiting well-defined cells and low-fat vacuoles in the cytoplasm, and (ALG): hepatocytes presenting fatty infiltration around the portal space. Original magnification 10X.

Fatty acids content in the animal liver after the trial: (A) C18:3 – (ALA) α-linolenic (n-3), (B) C18:3 – (GLA) γ- linolenic (n-6); (C) C20:5 – (EPA) eicosapenatenoic (n-3) and (D) C22:6 – (DHA) docosaexaenoic (n-3) - water (CON), fish oil (FIS), algae oil (ALG) and Echium oil (ECH). Bars followed by the same upperscrit letter do not differ (P<0.05). Data are mean±SE (raw data).

Discussion

The three sources of N-3 FA fatty acids were effective in improving the plasma lipid profile of the LDLr knockout mice. Among them, Echium oil provided the best results in terms of VLDL and total cholesterol reduction and contributed to the attenuation of hepatic steatosis. None of these oils was able to reduce the inflammation caused by the high fat diet, according to the biomarkers evaluated in this study.

The supplementation with fish and Echium oils increased EPA concentrations in liver homogenate. The capacity of SDA to increase EPA content in different tissues is still controversial. Zhang et al. [20] reported that the supplementation of LDLr knockout mice with Echium oil (10% of total energy intake) resulted in a significant enrichment of EPA in plasma lipids. According Harris [21] the direct dietary intake of SDA has been proposed to be another strategy to increase tissue EPA levels, since SDA does not depend of Δ6-desaturase to be converted in EPA.

LXRs and PPARs are nuclear receptors that play crucial role in the regulation of fatty acid metabolism [22]. The hypolipidaemic effect of algae and fish oils has been partially attributed to the downregulation of LXRα, with a subsequent inhibition of fatty acid synthesis, associated with the upregulation of PPARα, which promotes β-oxidation. Several studies have demonstrated that EPA and DHA reduce TG and VLDL acting as PPARα agonists and LXRα antagonists [5, 23, 24]. According to Chilton et al. [3], SDA and EPA reduce the level of mRNA for Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1C (SREBP1c), Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS) and stearoyl CoA desaturase 1 (SCD) in liver, suggesting that a possible mechanism to explain TG reduction would be associated with a decrease in the LXRα and consequently in the genes that codify proteins involved in fatty acids hepatic synthesis. This mechanism could be clearly observed to the both marine oils applied in our study, but not to the Echium oil. Animals supplemented with Echium oil showed the most significant VLDL reduction and attenuated steatosis, although no differences had been in regards to LXRα and PPARα expression. In fact, the mechanisms for the reduction of the plasma TG levels by Echium oil are unknown. Although the dose applied in our study was 5-fold lower, our results agree with those reported by Zhang et al. [20], who observed a reduction in TG and VLDL levels after Echium oil supplementation without changes in PPARα and LXRα expression. These results suggest that Echium oil can exert its beneficial effect on lipid metabolism and hepatic steatosis via mechanisms other than those reported for marine oils. In addition, it has been recommended [25] that studies involving SDA adopt a dose equivalent to EPA for supplementation. However, when this procedure was carried out in our study (Table 3), N-6/N-3 FA ratio of emulsion containing Echium oil (6.7) became lower than emulsions with algae (16.7) and fish (16.6) oils. Thus, differences observed in biomarkers between ECH group and the other two supplemented groups (ALG and FIS) can have also been influenced by these difference in N-6/N-3 FA ratio.

Mice supplemented with Echium oil showed reduction of N-6/N-3 ratio in liver (Table 5). According to Parker et al. [26] the increase of N-6/N-3 FA ratio in liver is associated with higher steatosis, since this condition can favor lipogenesis and inflammation processes. These findings have also been confirmed in human and animal studies [27, 28]. Thus, the lower N-6/N-3 FA ratio in liver homogenate can have contributed to the attenuation of steatosis observed in ECH group.

None of these three N-3 FA fatty acids sources was able to reduce serum inflammatory biomarkers. Ishihara et al. [29] observed that, in whole blood of Balb/c mice, the production of Tumor Necrosis Factor - α (TNFα) was suppressed by ALA, SDA and EPA supplementation. However, the dose applied by the authors was 53-fold higher than the dose used in our study. Our high-fat diet was formulated on basis of the diet applied by Safwat et al. [30] to promote hepatic steatosis in rats. The authors observed that after 10 weeks, the animals developed hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridaemia, and increased VLDL levels, but they observed no evidence of hepatic inflammation or fibrosis, suggesting that the hepatic steatosis was in its early stages. It is possible that the dose of EPA, DHA and SDA used in our study, although corresponding to an intake of 2 g/day for humans, was not sufficient to reduce the inflammation biomarkers when the process is at its initial steps. In spite of this, the high N6/N3 FA ratio present in the diet (16:1), typical of Western diet [5], may have annulled the potential LC N-3 PUFA anti-inflammatory action due to the higher availability of ARA than EPA as substrate to the oxidation mediated by cyclooxygenase and lipooxygenase enzymes.

Conclusions

In our study, the supplementation with three different sources of N-3 FA fatty acids was evaluated using LDLr knockout animals fed with a high fat diet. It was observed that the best combination of results, in terms of plasma lipid profile and steatosis, was achieved by the supplementation with Echium oil, and the mechanism involved in this favourable result seems to be different from those involved with EPA and DHA metabolism, maybe due to the lower N-6/N-3 FA ratio present in the liver of animals supplemented with Echium oil. Theoretically, it is possible to transfer a metabolic pathway for EPA and DHA synthesis from a marine organism to an oilseed crop plant [14]. However, while this option is not available, our study confirms that Echium oil represents an alternative as natural ingredient to be applied in functional foods to reduce cardiovascular disease risk.

Abbreviations

- ALA:

-

α - Linolenic acid

- ALG:

-

Algae oil group

- CON:

-

Control group

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- ECH:

-

Echium oil group

- EPA:

-

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- FAME:

-

Fatty acid methyl ester

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- FIS:

-

Fish oil group

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- ICAM:

-

Inter-cellular adhesion molecule

- IL- 6:

-

Interleukin 6

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

Receptor deficient mice

- LDLr:

-

Knockout mice

- LNA:

-

Linoleic acid

- LXR- α:

-

Liver X receptor α

- LC n-3 PUFA:

-

Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

- N-3 FA:

-

Omega 3 fatty acids

- N-6/N-3 FA:

-

Omega 6 fatty acids/omega 3 fatty acids

- PPAR-α:

-

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α

- SDA:

-

Stearidonic acid

- TG:

-

Triacylglycerol

- TNF- α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor –α

- VCAM:

-

Vascular cell adhesion molecule

- VLDL:

-

Very low density lipoprotein.

References

Blasbalg TL, Hibbeln JR, Ramsden CE, Majchrzak SF, Rawlings RR: Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011, 93: 950-62. 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643

Shapiro H, Tehilla M, Attal-Singer J, Bruck R, Luzzatti R, Singer P: The therapeutic potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2011, 30: 6-19. 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.06.001

Chilton FH, Rudel LL, Parks JS, Arm JP, Seeds MC: Mechanisms by which botanical lipids affect inflammatory disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 87: 498S-503S.

Balk EM, Lichtenstein AH, Chung M, Kupelnick B, Chew P, Lau J: Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on serum markers of cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2006, 189: 19-30. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.012

Adkins Y, Kelley DS: Mechanisms underlying the cardioprotective effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Nutr Biochem. 2010, 21: 781-92. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.12.004

Food and Drug Administration: Office of nutritional products, labeling, and dietary supplements, center for food safety and applied nutrition, US food and drug administration. Omega-3 fatty acids & coronary heart disease. Docket No. 2003Q-0401. http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm064923.htm. Accessed February 27, 2013.

Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ: Fish comsumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002, 106: 2747-57. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038493.65177.94

Wang C, Harris WS, Chung M, Lichtenstein AH, Balk EM, Kupelnick B, Jordan HS, Lau J: n-3 Fatty acids from fish or fish-oil supplements, but not α-linolenic acid, benefit cardiovascular disease outcomes in primary- and secondary-prevention studies: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 84: 5-17.

Barceló-Coblijn G, Murphy EJ: Alpha-linolenic acid and its conversion to longer chain n-3 fatty acids: benefits for human health and a role in maintaining tissue n-3 fatty acid levels. Prog Lipid Res. 2009, 48: 355-74. 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.07.002

Lemke SL, Vicini JL, Su H, Goldstein DA, Nemeth MA, Krul ES, Harris WS: Dietary intake of stearidonic acid-enriched soybean oil increases the omega-3 index: randomized, double-blind clinical study of efficacy and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 92: 766-75. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29072

Venegas-Calerón M, Sayanova O, Napier JA: An alternative to fish oils: metabolic engineering of oil-seed crops to produce omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 2010, 49: 108-19. 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.10.001

Poudyal H, Panchal SK, Diwan V, Brown L: Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: effects and emerging mechanisms of action. Prog Lipid Res. 2011, 50: 372-87. 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.06.003

Tahvonen RL, Schwab US, Linderborg KM, Mykkänen HM, Kallio HP: Black currant seed oil and fish oil supplements differ in their effects on fatty acid profiles of plasma lipids, and concentrations of serum total and lipoprotein lipids, plasma glucose and insulin. J Nutr Biochem. 2005, 16: 353-9. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.004

Damude HG, Kinney AJ: Engineering oilseed plants for a sustainable, land-based source of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids. 2007, 42: 179-85. 10.1007/s11745-007-3049-1

Yamazaki K, Fujikawa M, Hamazaki T, Yano S, Shono T: Comparison of the conversion rates of alpha-linolenic acid (18:3(n - 3)) and stearidonic acid (18:4(n - 3)) to longer polyunsaturated fatty acids in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992, 1123: 18-26. 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90166-S

Whelan J: Dietary stearidonic acid is a long chain (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid with potential health benefits. J Nutr. 2009, 139: 5-10.

AOAC: Official methods n. 996.06, Fat (Total, Saturated, and Monounsaturated) in Foods. Offic Meth Anal. 2002, 41: 20-24A.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972, 18: 499-502.

Tillmann T, Kamino K, Dasenbrock C, Kohler M, Morawietz G, Campo E, Cardesa A, Tomatis L, Mohr U: Quality control of three methods for lung tumorigenesis studies. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1999, 51: 99-104. 10.1016/S0940-2993(99)80078-5

Zhang P, Boudyguina E, Wilsom MD, Gebre AK, Parks JS: Echium oil reduces plasma lipids and hepatic lipogenic gene expression in apoB100-only LDL receptor knockout mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2008, 19: 655-63. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.08.005

Harris WS: Stearidonic acid-enhaced soybean oil: a plant-based source of n-3 fatty acids for foods. J Nutr. 2012, 142: 600S-604S. 10.3945/jn.111.146613

Yoshikawa T, Ide T, Shimano H, Yahagi N, Amemiya-Kudo M, Matsuzaka T, Yatoh S, Kitamine T, Okazaki H, Tamura Y, Sekiya M, Takahashi A, Hasty AH, Sato R, Sone H, Osuga J, Ishibashi S, Yamada N: Cross-talk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and liver X receptor (LXR) in nutritional regulation of fatty acid metabolism. I. PPARs suppress sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c promoter through inhibition of LXR signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2003, 17: 1240-54. 10.1210/me.2002-0190

Byrne CD: Fatty liver: role of inflammation and fatty acid nutrition. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010, 82: 265-71. 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.012

Harris WS, Miller M, Tighe AP, Davidson MH, Schaefer EJ: Omega-3 fatty acids and coronary heart disease risk: clinical and mechanistic perspectives. Atherosclerosis. 2008, 197: 12-24. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.008

Whelan J, Gouffon J, Zhao Y: Effects of dietary stearidonic acid on biomarkers of lipid metabolism. J Nutr. 2012, 142: 630S-634S. 10.3945/jn.111.149138

Parker HM, Johnson NA, Burdon CA, Cohn JS, O’ Connor HT, George J: Omega-3 supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2012, 56: 944-951. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.018

Sekiya M, Yahagi N, Matsuzaka T, Najima Y, Nakakuki M, Nagai R, Ishibashi S, Osuga J, Yamada N, Shimano H: Polyunsaturated fatty acids ameliorate hepatic steatosis in obese mice by SREBP-1 suppression. Hepatology. 2003, 38: 1529-1539.

Araya J, Rodrigo R, Videla LA, Thielemann L, Orellana M, Pettinelli P, Poniachik J: Increase in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid n-6/n-3 ratio in relation to hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Sci. 2004, 106: 635-643. 10.1042/CS20030326

Ishihara K, Komatsu W, Saito H, Shinohara K: Comparison of the effects of dietary α- Linolenic, stearidonic, and eicosapentaenoic acids on production of inflammatory mediators in mice. Lipids. 2002, 37: 481-6. 10.1007/s11745-002-0921-3

Safwat GM, Pisanò S, D’Amore E, Borioni G, Napolitano M, Kamal AA, Ballanti P, Botham KM, Bravo E: Induction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance by feeding a high-fat diet in rats: does coenzyme Q monomethyl ether have a modulatory effect?. Nutrition. 2009, 25: 1157-68. 10.1016/j.nut.2009.02.009

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to FAPESP (09/15649-7; 10/12042-1, 10/08225-3) for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

PBB conducted the research and wrote the manuscript. KRM performed part of the experiments. MMR participated in critical revision of the study. IAC contributed to the design of the study, analysis of data, drafting the manuscript and was responsible for the financial support. IAC had primary responsibility for the final content. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Botelho, P.B., Mariano, K.d.R., Rogero, M.M. et al. Effect of Echium oil compared with marine oils on lipid profile and inhibition of hepatic steatosis in LDLr knockout mice. Lipids Health Dis 12, 38 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-12-38

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-12-38