Abstract

Background

The emphasis placed on the activities of mobile teams in the detection of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) can at times obscure the major role played by fixed health facilities in HAT control and surveillance. The lack of consistent and detailed data on the coverage of passive case-finding and treatment further constrains our ability to appreciate the full contribution of the health system to the control of HAT.

Methods

A survey was made of all fixed health facilities that are active in the control and surveillance of gambiense HAT. Information on their diagnostic and treatment capabilities was collected, reviewed and harmonized. Health facilities were geo-referenced. Time-cost distance analysis was conducted to estimate physical accessibility and the potential coverage of the population at-risk of gambiense HAT.

Results

Information provided by the National Sleeping Sickness Control Programmes revealed the existence of 632 fixed health facilities that are active in the control and surveillance of gambiense HAT in endemic countries having reported cases or having conducted active screening activities during the period 2000-2012. Different types of diagnosis (clinical, serological, parasitological and disease staging) are available from 622 facilities. Treatment with pentamidine for first-stage disease is provided by 495 health facilities, while for second-stage disease various types of treatment are available in 206 health facilities only. Over 80% of the population at-risk for gambiense HAT lives within 5-hour travel of a fixed health facility offering diagnosis and treatment for the disease.

Conclusions

Fixed health facilities have played a crucial role in the diagnosis, treatment and coverage of at-risk-population for gambiense HAT. As the number of reported cases continues to dwindle, their role will become increasingly important for the prospects of disease elimination. Future updates of the database here presented will regularly provide evidence to inform and monitor a rational deployment of control and surveillance efforts. Support to the development and, if successful, the implementation of new control tools (e.g. new diagnostics and new drugs) is crucial, both for strengthening and expanding the existing network of fixed health facilities by improving access to diagnosis and treatment and for securing a sustainable control and surveillance of gambiense HAT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alongside the continued, albeit geographically limited, engagement of bilateral cooperation and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), it was the commitment of private sector in 2001 to support WHO that marked a turning point in the fight against human African trypanosomiasis (HAT)[1]. From that moment, control actions by the National Sleeping Sickness Control Programmes (NSSCPs) improved across the continent, and a dramatic decrease in the number of gambiense HAT cases followed. The annual number of cases reported to WHO by disease-endemic countries dropped by 73% from 25,865 in 2000 to 7,106 in 2012[2].

This observed drop in cases reported was accompanied and made possible by strengthened capacity of NSSCPs to perform active and passive case-detection, as well as an improvement in reporting[3]. The withdrawal of NGOs which focused on HAT emergencies (while in the early 2000 31 NGO-run programmes were active, in December 2012 only two were registered) and the difficulties in recruiting patients for clinical trials to develop new tools for HAT control, support the notion that the trend reported over the last decade reflects a real abatement of disease transmission in the field. Furthermore, substantially improved management and reporting of data – embodied in the HAT Atlas initiative[4, 5] – also contribute to the reliability of the available epidemiological information.

Nevertheless, because of the occurrence of gambiense HAT in remote rural areas and the weakness of health systems, an unspecified number of sleeping sickness cases still escape detection and reporting. For gambiense HAT little is known of the true extent of this underreporting phenomenon, and specific studies are needed to estimate its magnitude and thereby accurately to assess the progress made in curbing transmission globally. At the same time, some insights into the likelihood of underdetection/underreporting can be gained by looking at the distribution and intensity of control and surveillance activities involving both mobile teams and fixed health facilities.

Arguably, a narrow focus on active case-finding activities alone may give the impression that only a small proportion of the population at-risk of HAT is reached by control and surveillance activities. In fact, while recent estimates put the population at risk of gambiense HAT at approximately 57 million people[6, 7], only an average of 2 million are screened every year by mobile teams (period 2000-2012) (data not shown). Active surveillance alone appears inadequate to ensure a satisfactory coverage of populations at-risk of gambiense HAT, and consequently it may seem reasonable to question the reported abatement in disease transmission. However, the role played by fixed health facilities embedded in the health system must be taken into account if a complete picture of the coverage and outcomes of HAT control and surveillance is to be drawn.

Indeed, control of gambiense HAT has relied, in addition to the impressive and well known active case-finding surveys carried out by mobile teams, also on the quiet contribution of passive screening performed in fixed health structures. For example, in the period 2000-2012, 93,561 cases of gambiense HAT (48.9% of the reported total) were diagnosed by passive case-finding carried out in fixed health facilities (Table 1).

However, the lack of consistent and detailed data on the extent, capacities and coverage of passive case-finding and treatment constrains our ability to appreciate its full relevance in HAT control and surveillance. The present study aims to contribute to filling this gap.

The paper explores the geographic distribution and the diagnostic and treatment capabilities of fixed health facilities involved in gambiense HAT control and surveillance. It also aims to estimate the at-risk population potentially covered by passive case-finding and treatment by using Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

The inventory of this passive surveillance and treatment network provides the dimension of what is available today. At the same time, it gives insights into the work needed in terms of capacity development and improvement and expansion of the network, aiming at covering the whole population at risk.

The paper focuses on all endemic countries having reported gambiense HAT cases or having conducted active screening activities during the period 2000-2012 (i.e. Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Togo and Uganda). Capabilities for diagnosis and treatment in non-endemic countries have been reviewed elsewhere[8].

Rhodesiense HAT being characterized by different epidemiological patterns and approaches to disease control is not directly considered in this study.

Methods

Data collection

Fixed health facilities active in gambiense HAT control and surveillance were identified through direct interviews with the coordinators of the NSSCPs. Standardized forms were circulated requesting information on the name and location of the health structures, and on their diagnostic and treatment capabilities for HAT. The survey started in December 2012 and was completed in August 2013.

Diagnostic capabilities were categorized as follows. Clinical diagnosis (DxC) refers to the ability of health centres systematically to raise a clinical suspicion of trypanosomal infection and refer the suspect to the next level for further diagnosis or, if available, to perform it in the same facility. Serological diagnosis (DxS) concerns the capability of performing serological tests, thus identifying serological suspects. In this context, the serological test considered is the card agglutination test for trypanosomiasis – CATT[9]. Parasitological diagnosis (DxP) pertains to the competence of the health centre to execute any type of parasitological test in order to confirm trypanosome infection in clinical or serological suspects through direct observation of the parasite in body fluids. Health centres were also classified according to their capability to carry out the stage determination (DxPh) by examination of cerebrospinal fluid obtained through lumbar puncture.

Treatment capabilities were categorized in a similar fashion. This includes treatment of first stage infections with pentamidine (Tx1P), and treatment of second-stage cases with melarsoprol (Tx2M), eflornithine (Tx2E) or nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy – NECT (Tx2N).

All data on the HAT health centres provided by NSSCPs were harmonized and assembled in a database. Mapping was subsequently carried out using geo-referencing procedures already described[10].

Data analysis

Physical accessibility to HAT diagnosis and treatment was estimated through a cost-distance function. This type of geographical functions determines the shortest weighted distance (or least cumulated travel time-cost) from any location to the nearest destination. In our study, travel cost was measured in time units, and the destinations were represented by health facilities having capabilities for HAT diagnosis and treatment.

The time-cost of travel was derived from a recently generated ‘friction’ layer for Africa[11]. In this type of geo-spatial dataset, such GIS maps as land cover, water bodies, slope and road network are combined to empirically derived travel speeds to estimate a pixel-by-pixel travel time. Various means of transportation are contemplated, depending on the network infrastructure and terrain. The friction grid utilized in this study has a spatial resolution of approximately 1-km (i.e. 30 arcseconds). Importantly, affordability (or economic cost of travel) is not considered in this model.

The least time-cost path function enabled a map of accessibility to be generated across the study countries, whereby the shortest travel time to the closest HAT diagnostic or treatment facility was estimated for each pixel. This enabled population coverage to be assessed for different cumulated travel times. In particular, results are provided for three different travel time-cost thresholds: 1, 3 and 5 hours.

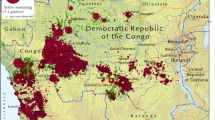

Total population coverage was subsequently stratified by level of gambiense HAT risk. To this end, a previously derived risk surface for gambiense HAT was used, which was based on spatial smoothing of HAT reported cases and human population layers[7]. From this dataset three broad categories of risk were extracted: high and very high (≥ 1 HAT case per 103 people per annum – p.a.), moderate (≥ 1 HAT case per 104 people and < 1 HAT case per 103 people p.a.), and low and very low (≥ 1 HAT case per 106 people and < 1 HAT case per 104 people p.a.) (Figure 1).

The risk of T. b. gambiense infection in Africa. Adapted from[7]. Risk is based on the reported number of gambiense HAT cases in the period 2000-2009 and on Landscan™ human population layers for the same period[6]. As a backdrop, the predicted distribution of the palpalis group of tsetse flies is provided. The palpalis group (Genus: Glossina, subgenus: Nemorhina) includes all the major vector species of gambiense HAT.

For estimating both the total population coverage and the coverage of at-risk population, the dataset Landscan™ 2009 was used[12]. This was the same layer previously used to estimate at-risk population[7], and therefore it provided a precise baseline for comparison. Uncertainties and limitations of the available global human population layers, including Landscan™, have been discussed in a number of papers (e.g.[13, 14]).

Ethical considerations

The study is based on the analysis of a database obtained through administrative data provided by health authorities in the selected countries. No experimental research was carried on humans nor on animals. The database does not contain any individual or attributable information. Therefore for this study no Institutional Review Board was sought and the Helsinki declaration and Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research were not applicable.

Results

Fixed health facilities for diagnosis and treatment of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis

Information provided by the NSSCPs revealed the existence of 632 fixed health facilities that are involved in the control and surveillance of gambiense HAT in disease-endemic countries.

Their diagnostic and treatment capacities are summarized in Table 2, while the complete list of health facilities including the names and geographical coordinates is provided in Additional file1.

Diagnosis is available in 622 facilities, 84.2% of which are found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Although all of the 622 centres are able to identify clinical suspects, only 56% of them are able to go further performing serological test. The number of centres able to carry out parasitological diagnosis (DxP) and disease staging (DxPh) decreases to 49% and 39% respectively, mainly due to the need for complex tools and highly skilled staff.

Access to treatment for gambiense HAT is slightly more limited (495 health centres – 81.6% of which in DRC). While all of these centres are able to offer treatment for first-stage disease, only 36.4% can offer first line treatment for second-stage disease (Tx2N). This is mainly due to the challenges inherent in the distribution and the administration of NECT.

Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of the health structures involved in gambiense HAT diagnosis (A) and treatment (B). In this figure, no distinction is made between different levels of diagnostic or treatment capabilities. Separate maps showing the distribution of centres able to perform the various types of diagnosis and treatment are provided in Additional file2. Distribution maps at the national and focus level will be made available from the WHO HAT web site (http://www.who.int/trypanosomiasis_african/en/).

Geographic distribution of fixed health facilities having capacities for gambiense HAT diagnosis (A) and treatment (B). Data were collected by WHO between December 2012 and August 2013 from National Sleeping Sickness Control Programmes in the study countries (i.e. Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Togo and Uganda).

Diagnosis coverage by fixed health facilities of population at-risk of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis

The map of physical accessibility to HAT diagnostic facilities is shown in Figure 3. In the study countries, we estimate that 31, 85 and 154 million people are respectively within 1, 3 and 5 hours travel of a facility with capacity for HAT diagnosis.

Travel time (or physical accessibility) to health facilities having capabilities for diagnosis of gambiense HAT [hours]. Physical accessibility was calculated through a cost-distance function. Travel cost was measured in time units, and the destinations were represented by health facilities having capabilities for HAT diagnosis (Figure 2A). The time-cost of travel was derived from a ‘friction’ layer for Africa[11].

Focusing on gambiense HAT at-risk population, their coverage by diagnostic facilities is summarized in Table 3. Our analysis indicates that 23.4, 40.2, and 47.4 million people at risk are respectively within 1, 3 and 5 hours travel of a facility with capacity for gambiense HAT diagnosis. This corresponds to 41, 71, and 83% of the total at-risk population. For the 10-hour travel threshold, the coverage of at-risk population is 96% (Additional file3).

Coverage is not homogeneous across the risk categories, with higher risk categories being characterized by comparatively better coverage. For example, for populations at high and very high risk, coverage is estimated at 48, 77 and 87% for the travel time thresholds of 1, 3 and 5 hours respectively. These percentages decrease for moderate and for low and very low risk categories – the health systems deploying better equipped facilities and skilled staff in areas where transmission of the disease is more intense.

Full details for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all risk categories are provided in Additional file3. These country-level data indicate that there are no major differences between countries in terms of the proportion of at-risk population potentially covered by HAT diagnostic facilities.

Cost-distance analysis was also conducted separately for the different types of diagnosis. Results are summarized in Table 4, while detailed data for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all risk categories are provided in Additional file4.

Treatment coverage by fixed health facilities of population at-risk of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis

The map of physical accessibility to HAT treatment facilities is shown in Additional file5. We estimate that in the study countries 27, 73 and 133 million people are respectively within 1, 3 and 5 hours travel of a facility with capacity for gambiense HAT treatment.

Looking at population at risk, the coverage by treatment facilities is summarized in Table 5, while full details for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all risk categories are provided in Additional file6. Our analysis indicates that 21.6, 38.8, and 46.5 million people at risk are respectively within 1, 3 and 5 hours travel of a facility with capacity for gambiense HAT treatment. This corresponds to 38, 68, and 82% of the total population at risk. For the 10-hour travel threshold, the coverage of at-risk population is 95% (Additional file6).

Cost-distance analysis was also conducted separately for the different types of treatment. Results are summarized in Table 6, while detailed data for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all risk categories are provided in Additional file7. All facilities involved in gambiense HAT treatment have capacity for treatment of the first-stage of the disease. Lower coverage is available for the treatment of the second-stage of the disease.

Conclusions

The decreasing trend in the reported number of gambiense HAT cases has led to target the disease for elimination in the WHO Road Map on Neglected Tropical Disease[15]. However, the low number of people at risk covered by active case-finding surveys is often cited to raise doubts on the reliability of the reported figures. In this study we show that a narrow focus on the intensity of active case-finding is inadequate to fully describe the coverage of HAT control and surveillance activities. Gambiense HAT is a chronic disease that is characterized by a sufficiently long duration[16] to allow passive case detection in fixed health facilities to complement the coverage of active case detection. At the same time, the interval between infection and diagnosis in fixed health structure allowed the persistence and the spread of the disease. As a matter of fact, active screening by mobile teams that has been decisive in tackling the worrisome situation of HAT at the beginning of this century, can only be conducted in selected villages of determined areas of disease transmission. Covered locations are rarely visited more than once a year, and the interval between successive visits is often longer. Even on the occasion when a village is visited by a mobile team, coverage is unfortunately far from 100%[17]. Because of these limitations of active case-finding, the role of the fixed health facilities in gambiense HAT transmission areas has been extremely important to fill a part of the screening and coverage gap. Indeed, passive screening detected 93,561 cases during the period 2000-2012, which represent approximately half of the total cases reported.

The present analysis reveals the existence of a network of fixed health facilities involved in the passive control and surveillance of gambiense HAT. A census of the diagnosis and treatment capabilities was made for the 632 fixed health facilities identified. It must be stressed that our survey did not address the quality control of services provided in the fixed health facilities involved in HAT control and surveillance, nor did it explore population attendance. The results illustrate the substantial attempts made by the health system in disease-endemic countries in tackling the disease, although efforts on capacity building and equipment must be undertaken to get this network fully operational. Over 80% of the population at-risk lives within 5-hour travel of a fixed health facility offering diagnosis and treatment for gambiense HAT. The results also indicate that coverage for clinical diagnosis is the most widely available, while access to serological and parasitological diagnosis becomes progressively more difficult. This observation supports the notion that that the current test for serological screening (CATT), although very useful for serological mass screening by mobile teams, does not fulfil the requirements for its use in the rural health facilities where gambiense HAT is endemic – most notably because of the format (50 tests per vial) and the need for cold chain and electric power. The new Individual Screening Tests (IST, often called rapid diagnostic tests) do not require cold chain nor electric power, and they hold the potential to expand the network of fixed health facilities able to detect serological suspects – which is presently available only in 55.6% of the facilities able to detect clinical suspects – and therefore they could widen and improve access to gambiense HAT diagnosis[18]. Concerning parasitological diagnosis, the coverage gap can partly be ascribed to the cumbersome nature of and the skilled staff required by the current parasitological diagnostic tests. First evaluation on clinical samples of new molecular techniques procedures (i.e. the loop-mediated isothermal amplification — LAMP) has shown similar performance to conventional PCR[19]. However, LAMP is still more complicated than the parasitological methods available and requires further studies to assess its accuracy. Therefore it does not fulfil all requirements to replace the laborious process for demonstrating the presence of the parasite in body fluids of people giving positive results in serological screening tests. At this point in time, the weakness of laboratory capacities in the rural health facilities remains a challenge for parasitological diagnosis of gambiense HAT[20].

Concerning treatment, thanks to the fact that some cases diagnosed and staged in highest centres as first stage can be referred for treatment to lower health centres, 82% of the people at risk of gambiense HAT have access to a centre offering treatment for first-stage patients within a 5-hour travel-time, while 69% have access to a health care facility administering the recommended first line treatment for second-stage gambiense HAT (NECT) within the same travel-time threshold. These figures show that people affected by second-stage gambiense HAT have to make more efforts to receive appropriate treatment. This is mainly because of the complexity of administration and the demanding logistics of current first line treatment for second-stage gambiense HAT. The hopes to overcome these hurdles rest in the ongoing development of new drugs not requiring skilled staff and complex equipment (i.e. fexinidazole and oxaborol)[21, 22]. An oral, safe drug, effective for both stages of the disease could greatly improve access to treatment; at the same time, it would remove the need for staging through lumbar puncture, which is not always well accepted and can only be offered by 38.5% of the facilities involved in the treatment of gambiense HAT.

In the light of the new challenges to achieve sustainable elimination of gambiense HAT, the meeting on HAT elimination held in Geneva in December 2012[23] emphasized the importance of maintaining mobile teams in selected areas and in particular epidemiological circumstances, as well as the value of reinforcing the health system and involving it fully in passive control and surveillance. This message has been voiced by the disease-endemic countries[23] and in a recent WHO Expert Committee on HAT[2]. Strengthening and expanding fixed health facilities involved in control and surveillance to reach 100% of people at risk require the provision of appropriate tools and capacity building. Support from both international partners and from operational national teams is needed to monitor and evaluate the network, as well as to collect and analyze data obtained and to provide appropriate response.

It is important to note that two factors have contributed to the good performance of passive detection in recent years: the knowledge of the disease among health staff and among affected communities. This knowledge facilitates diagnosis both at the level of fixed health facilities, but also at the community level, where infected individuals can be identified and advised to visit a hospital for proper diagnosis and care. Retirement of skilled staff and the decreasing number of cases in the community reduce familiarity with the disease and can greatly decrease the effectiveness of passive diagnosis. A need exists therefore for capacity building of health staff, for less complicated control tools, and for awareness-raising campaigns among populations at risk of gambiense HAT.

Moreover, low attendance rates in some health care facilities (the average annual attendance rate of health services in DRC is estimated at 0.15 per inhabitant[24]) are unfortunately not only due to difficulties at the technical level (i.e. skilled staff and adapted tools) but are also at the structural level. Indeed, attendance of populations to health facilities does not depend only on physical accessibility, but also on economic and socio-cultural factors and on the perceived benefit of skilled care[25]. Furthermore, due to the location of the main fixed health structure (towns), passive screening is likely to address more urban than rural people. Therefore, attention must be paid to appreciate the level of attendance of population at risk of HAT (e.g. number of people screen by new IST by year and by village of origin), as well as their characteristics (sex, age, urban/rural, activities, etc.) in order to evaluate the coverage of fixed health facilities in the case of HAT surveillance.

On the other hand, attendance to facilities providing services of diagnosis of HAT does not mean that the tests available are applied automatically. Several visits are sometimes necessary before HAT diagnostic tools are applied, and awareness of staff in the presence of the disease is required to prescribe their use[26]. Continuous monitoring and evaluation are therefore needed, with a view to ensuring that an effective surveillance of gambiense HAT is in place to sustain the disease elimination process.

The data and coverage estimates herewith presented will be regularly updated, thus continuously providing evidence to inform a rational deployment of control and surveillance efforts. Coverage estimates of population at risk will also provide indicators to monitor the process of elimination of gambiense HAT[23].

References

WHO: Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness): epidemiological update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006, 81 (8): 71-80.

WHO: Control and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis. Technical Report Series. 2013, Geneva: World Health Organization

Simarro PP, Jannin J, Cattand P: Eliminating human african trypanosomiasis: where do we stand and what comes next. PLoS Med. 2008, 5 (2): e55-10.1371/journal.pmed.0050055.

Cecchi G, Courtin F, Paone M, Diarra A, Franco JR, Mattioli RC, Simarro PP: Mapping sleeping sickness in Western Africa in a context of demographic transition and climate change. Parasite. 2009, 16 (2): 99-106. 10.1051/parasite/2009162099.

Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Paone M, Franco JR, Diarra A, Ruiz JA, Fèvre EM, Courtin F, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG: The Atlas of human African trypanosomiasis: a contribution to global mapping of neglected tropical diseases. Int J Health Geogr. 2010, 9: 57-10.1186/1476-072X-9-57.

Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Franco JR, Paone M, Fèvre EM, Diarra A, Ruiz JA, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG: Risk for human african trypanosomiasis, central africa, 2000-2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17 (12): 2322-2324. 10.3201/eid1712.110921.

Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Franco JR, Paone M, Fèvre EM, Diarra A, Ruiz JA, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG: Estimating and mapping the population at risk of sleeping sickness. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012, 6 (10): e1859-10.1371/journal.pntd.0001859.

Simarro PP, Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, Diarra A, Ruiz JA, Jannin JG: Human African trypanosomiasis in non-endemic countries (2000-2010). J Travel Med. 2012, 19 (1): 44-53. 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00576.x.

Magnus E, Vervoort T, Van Meirvenne N: A card-agglutination test with stained trypanosomes (CATT) for the serological diagnosis of TB gambiense trypanosomiasis. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1977, 58 (3): 169-176.

Cecchi G, Paone M, Franco JR, Fèvre E, Diarra A, Ruiz J, Mattioli R, Simarro PP: Towards the Atlas of human African trypanosomiasis. Int J Health Geogr. 2009, 8: 15-10.1186/1476-072X-8-15.

Tatem AJ, Hemelaar J, Gray RR, Salemi M: Spatial accessibility and the spread of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants. AIDS. 2012, 26 (18): 2351-2360. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359a904.

Dobson J, Bright E, Coleman P, Durfee R, Worley B: LandScan: a global population database for estimating populations at risk. Photogramm Eng Remote Sensing. 2000, 66 (7): 849-857.

Tatem AJ, Campiz N, Gething PW, Snow RW, Linard C: The effects of spatial population dataset choice on estimates of population at risk of disease. Population Health Metrics. 2011, 9 (1): 4-10.1186/1478-7954-9-4.

Linard C, Tatem AJ: Large-scale spatial population databases in infectious disease research. Int J Health Geogr. 2012, 11: 7-10.1186/1476-072X-11-7.

WHO: Accelerating Work To Overcome Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Roadmap For Implementation. 2012, Geneva: World Health Organization

Checchi F, Filipe JA, Barrett MP, Chandramohan D: The natural progression of Gambiense sleeping sickness: what is the evidence?. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008, 2 (12): e303-10.1371/journal.pntd.0000303.

Mpanya A, Hendrickx D, Vuna M, Kanyinda A, Lumbala C, Tshilombo V, Mitashi P, Luboya O, Kande V, Boelaert M, Lefèvre P, Lutumba P: Should I get screened for sleeping sickness? a qualitative study in kasai province, democratic republic of congo. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012, 6 (1): e1467-10.1371/journal.pntd.0001467.

Buscher P, Gilleman Q, Lejon V: Rapid diagnostic test for sleeping sickness. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368 (11): 1069-1070. 10.1056/NEJMc1210373.

Mitashi P, Hasker E, Mumba Ngoyi D, Patient Pyana P, Lejon V, Van der Veeken W, Lutumba P, Büscher P, Boelaert M, Deborggraeve S: Diagnostic accuracy of Loopamp™ trypanosoma brucei detection Kit for diagnosis of human African trypanosomiasis in clinical samples. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. In Press

Lejon V, Jacobs J, Simarro P: Elimination of sleeping sickness hindered by difficult diagnosis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013, 91: 718-10.2471/BLT.13.126474.

Torreele E, Bourdin Trunz B, Tweats D, Kaiser M, Brun R, Mazue G, Bray MA, Pecoul B: Fexinidazole–a new oral nitroimidazole drug candidate entering clinical development for the treatment of sleeping sickness. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010, 4 (12): e923-10.1371/journal.pntd.0000923.

Jacobs RT, Nare B, Wring SA, Orr MD, Chen D, Sligar JM, Jenks MX, Noe RA, Bowling TS, Mercer LT, Rewerts C, Gaukel E, Owens J, Parham R, Randolph R, Beaudet B, Bacchi CJ, Yarlett N, Plattner JJ, Freund Y, Ding C, Akama T, Zhang YK, Brun R, Kaiser M, Scandale I, Don R: SCYX-7158, an orally-active benzoxaborole for the treatment of stage 2 human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011, 5 (6): e1151-10.1371/journal.pntd.0001151.

WHO: Report Of A WHO Meeting On Elimination Of African Trypanosomiasis (Trypanosoma brucei gambiense). 2013, Geneva: World Health Organization

Wembonyama S, Mpaka S, Tshilolo L: [Medicine and health in the democratic republic of congo: from independence to the third republic]. Med Trop (Mars). 2007, 67 (5): 447-457.

Gabrysch S, Campbell OM: Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009, 9: 34-10.1186/1471-2393-9-34.

Hasker E, Lumbala C, Mbo F, Mpanya A, Kande V, Lutumba P, Boelaert M: Health care-seeking behaviour and diagnostic delays for human african trypanosomiasis in the democratic republic of the congo. Trop Med Int Health. 2011, 16 (7): 869-874. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02772.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the coordinators of the National Sleeping Sickness Control Programmes that provided data for the analysis: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Togo and Uganda.

The activities described in this paper are an initiative of the Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases - WHO. They were implemented through a technical collaboration between WHO and FAO in the framework of PAAT. The contribution of FAO is supported by the Government of Italy through the FAO Trust Fund for Food Security and Food Safety (Project GTFS/RAF/474/ITA – Improving food security in sub-Saharan Africa by supporting the progressive reduction of tsetse-transmitted trypanosomosis in the framework of the NEPAD).

Disclaimers

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on the maps presented in this paper do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO and FAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of WHO and FAO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PPS coordinated the study. GC supervised the technical aspects related to data management and GIS, and conducted the analysis. PPS and GC jointly drafted the manuscript. MP implemented geo-positioning procedures and managed the data. PPS, JRF, AD and JAR collated and screened the data used as input. PPS, JRF, RCM and JGJ coordinated and supervised the collaboration between WHO and FAO in the framework of the Programme Against African Trypanosomosis (PAAT). All authors have contributed to conceptualizing the manuscript, and commented on and approved the final draft.

Electronic supplementary material

12942_2013_577_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1:Fixed health facilities that are active in the control and surveillance of gambiense HAT. Table S1. Fixed health facilities that are active in the control and surveillance of gambiense HAT in Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Togo and Uganda. Table S2. Fixed health facilities that are active in the control and surveillance of gambiense HAT in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (DOCX 181 KB)

12942_2013_577_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Additional file 2:Geographic distribution of fixed health facilities having capacities for diagnosis of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. Figure S1. Geographic distribution of fixed health facilities having capacities for clinical diagnosis of gambiense HAT (A) and serological diagnosis (B). Figure 2. Geographic distribution of fixed health facilities having capacities for parasitological diagnosis of gambiense HAT (A) and stage determination (B). Figure 3. Geographic distribution of fixed health facilities having capacities for treatment of gambiense HAT first-stage infections with pentamidine (A) and second-stage infection with melarsoprol (B). Figure 4. Geographic distribution of fixed health facilities having capacities for treatment of gambiense HAT second-stage infections with eflornithine (A) and with nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (B). (DOCX 3 MB)

12942_2013_577_MOESM3_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 3:Diagnosis coverage by fixed health facilities of population at-risk of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. Diagnosis coverage is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. (XLSX 57 KB)

12942_2013_577_MOESM4_ESM.zip

Additional file 4:Coverage for the different types of diagnosis. Annex_DxC.xlsx: Clinical diagnosis coverage is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. Annex_DxS.xlsx: Serological diagnosis coverage is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. Annex_DxP.xlsx: Parasitological diagnosis coverage is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. Annex_DxPh.xlsx: Disease staging coverage is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. (ZIP 200 KB)

12942_2013_577_MOESM5_ESM.docx

Additional file 5:Travel time (or physical accessibility) to health facilities having capabilities for treatment of gambiense HAT [hours]. Physical accessibility was calculated through a cost-distance function. Travel cost was measured in time units, and the destinations were represented by health facilities having capabilities for HAT treatment. The time-cost of travel was derived from a ‘friction’ layer for Africa[11]. (DOCX 1 MB)

12942_2013_577_MOESM6_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 6:Treatment coverage by fixed health facilities of population at-risk of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. Treatment coverage is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. (XLSX 55 KB)

12942_2013_577_MOESM7_ESM.zip

Additional file 7:Coverage for the different types of treatment. Annex_Tx1P.xlsx: Coverage for treatment of first-stage infection with pentamidine is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. Annex_Tx2M.xlsx: Coverage for treatment of second-stage infection with melarsoprol is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. Annex_Tx2E.xlsx: Coverage for treatment of second-stage infection with eflornithine is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. Annex_Tx2N.xlsx: Coverage for treatment of second-stage infection with nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy is provided for a range of travel-times, for all study countries and for all HAT-risk categories. (ZIP 197 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Simarro, P.P., Cecchi, G., Franco, J.R. et al. Mapping the capacities of fixed health facilities to cover people at risk of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. Int J Health Geogr 13, 4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-4