Abstract

There is growing evidence of a distinct set of freshly-emitted air pollutants downwind from major highways, motorways, and freeways that include elevated levels of ultrafine particulates (UFP), black carbon (BC), oxides of nitrogen (NOx), and carbon monoxide (CO). People living or otherwise spending substantial time within about 200 m of highways are exposed to these pollutants more so than persons living at a greater distance, even compared to living on busy urban streets. Evidence of the health hazards of these pollutants arises from studies that assess proximity to highways, actual exposure to the pollutants, or both. Taken as a whole, the health studies show elevated risk for development of asthma and reduced lung function in children who live near major highways. Studies of particulate matter (PM) that show associations with cardiac and pulmonary mortality also appear to indicate increasing risk as smaller geographic areas are studied, suggesting localized sources that likely include major highways. Although less work has tested the association between lung cancer and highways, the existing studies suggest an association as well. While the evidence is substantial for a link between near-highway exposures and adverse health outcomes, considerable work remains to understand the exact nature and magnitude of the risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Approximately 11% of US households are located within 100 meters of 4-lane highways [estimated using: [1, 2]]. While it is clear that automobiles are significant sources of air pollution, the exposure of near-highway residents to pollutants in automobile exhaust has only recently begun to be characterized. There are two main reasons for this: (A) federal and state air monitoring programs are typically set up to measure pollutants at the regional, not local scale; and (B) regional monitoring stations typically do not measure all of the types of pollutants that are elevated next to highways. It is, therefore, critical to ask what is known about near-highway exposures and their possible health consequences.

Here we review studies describing measurement of near-highway air pollutants, and epidemiologic studies of cardiac and pulmonary outcomes as they relate to exposure to these pollutants and/or proximity to highways. Although some studies suggest that other health impacts are also important (e.g., birth outcomes), we feel that the case for these health effects are less well developed scientifically and do not have the same potential to drive public policy at this time. We did not seek to fully integrate the relevant cellular biology and toxicological literature, except for a few key references, because they are so vast by themselves.

We started with studies that we knew well and also searched the engineering and health literature on Medline. We were able to find some earlier epidemiologic studies based on citations in more recent articles. We include some studies that assessed motor vehicle-related pollutants at central site monitors (i.e., that did not measure highway proximity or traffic) because we feel that they add to the plausibility of the associations seen in other studies. The relative emphasis given to studies was based on our appraisal of the rigor of their methodology and the significance of their findings. We conclude with a summary and with recommendations for policy and further research.

Motor vehicle pollution

It is well known that motor vehicle exhaust is a significant source of air pollution. The most widely reported pollutants in vehicular exhaust include carbon monoxide, nitrogen and sulfur oxides, unburned hydrocarbons (from fuel and crankcase oil), particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and other organic compounds that derive from combustion [3–5]. While much attention has focused on the transport and transformation of these pollutants in ambient air – particularly in areas where both ambient pollutant concentrations and human exposures are elevated (e.g., congested city centers, tunnels, and urban canyons created by tall buildings), less attention has been given to measuring pollutants and exposures near heavily-trafficked highways. Several lines of evidence now suggest that steep gradients of certain pollutants exist next to heavily traveled highways and that living within these elevated pollution zones can have detrimental effects on human health.

It should be noted that many different types of highways have been studied, ranging from California "freeways" (defined as multi-lane, high-speed roadways with restricted access) to four-lane (two in each direction), variable-speed roadways with unrestricted access. There is considerable variation in the literature in defining highways and we choose to include studies in our review that used a broad range of definitions (see Table 1).

It should also be noted that there may be significant heterogeneity in the types and amounts of vehicles using highways. The typical vehicle fleet in the US is composed of passenger cars, sports utility vehicles, motorcycles, pickup trucks, vans, buses, and small, medium, and large trucks. The composition and size of a fleet on a given highway may vary depending on the time of day, day of the week, and use restrictions for certain classes of vehicles. Fleets may also vary in the average age and state of repair of vehicles, the fractions of vehicles that burn diesel and gasoline, and the fraction of vehicles that have catalytic converters. These factors will influence the kinds and amounts of pollutants in tailpipe emissions. Similarly, driving conditions, fuel chemistry, and meteorology can also significantly impact emissions rates as well as the kinds and concentrations of pollutants present in the near-highway environment. These factors have rarely been taken into consideration in health outcome studies of near-highway exposure.

Based on our review of the literature, the pollutants that have most consistently been reported at elevated levels near highways include ultrafine particles (UFP), black carbon (BC), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and carbon monoxide (CO). In addition, PM2.5, and PM10 were measured in many of the epidemiologic studies we reviewed. UFP are defined as particles having an aerodynamic diameter in the range of 0.005 to 0.1 microns (um). UFP form by condensation of hot vapors in tailpipe emissions, and can grow in size by coagulation. PM2.5 and PM10 refer to particulate matter with aerodynamic diameters of 2.5 and 10 um, respectively. BC (or "soot carbon") is an impure form of elemental carbon that has a graphite-like structure. It is the major light-absorbing component of combustion aerosols. These various constituents can be measured in real time or near-real time using particle counters (UFP) and analyzers that measure light absorption (BC and CO), chemiluminescence (NOx), and weight (PM2.5 and PM10). Because UFP, NOx, BC, and CO derive from a common source – vehicular emissions – they are typically highly inter-correlated.

Air pollutant gradients near highways

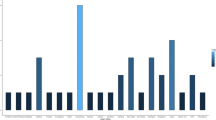

Several recent studies have shown that sharp pollutant gradients exist near highways. Shi et al. [6] measured UFP number concentration and size distribution along a roadway-to-urban-background transect in Birmingham (UK), and found that particle number concentrations decreased nearly 5-fold within 30 m of a major roadway (>30,000 veh/d). Similar observations were made by Zhu et al. [7, 8] in Los Angeles. Zhu et al. measured wind speed and direction, traffic volume, UFP number concentration and size distribution as well as BC and CO along transects downwind of a highway that is dominated by gasoline vehicles (Freeway 405; 13,900 vehicles per hour; veh/h) and a highway that carries a high percentage of diesel vehicles (Freeway 710; 12,180 veh/h). Relative concentrations of CO, BC, and total particle number concentration decreased exponentially between 17 and 150 m downwind from the highways, while at 300 m UFP number concentrations were the same as at upwind sites. An increase in the relative concentrations of larger particles and concomitant decrease in smaller particles was also observed along the transects (see Figure 1). Similar observations were made by Zhang et al. [9] who demonstrated "road-to-ambient" evolution of particle number distributions near highways 405 and 710 in both winter and summer. Zhang et al. observed that between 30–90 m downwind of the highways, particles grew larger than 0.01 um due to condensation, while at distances >90 m, there was both continued particle growth (to >0.1 um) as well as particle shrinkage to <0.01 um due to evaporation. Because condensation, evaporation, and dilution alter size distribution and particle composition, freshly-emitted UFP near highways may differ in chemical composition from UFP that has undergone atmospheric transformation during transport to downwind locations [10].

Two studies in Brisbane (Australia) highlight the importance of wind speed and direction as well as contributions of pollutants from nearby roadways in tracking highway-generated pollutant gradients. Hitchins et al. [11] measured the mass concentrations of 0.1–10 um particles as well as total particle number concentration and size distribution for 0.015–0.7 um particles near highways (2,130–3,400 veh/h). Hitchens et al. observed that the distance from highways at which number and mass concentrations decreased by 50% varied from 100 to 375 m depending on the wind speed and direction. Morawska et al. [12] measured the changes in UFP number concentrations along horizontal and vertical transects near highways to distinguish highway and normal street traffic contributions. It was observed that UFP number concentrations were highest <15 m from highways, while 15–200 m from highways there was no significant difference in UFP number concentrations along either horizontal or vertical transects – presumably due to mixing of highway pollutants with emissions from traffic on nearby, local roadways.

In addition to UFP, other pollutants – such as PM2.5, PM10, NO2 (nitrogen dioxide), VOCs (volatile organic compounds), and particle-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PPAH) – have been studied in relation to heavily-trafficked roadways. Fischer et al. [13] measured PM2.5, PM10, PPAH, and VOC concentrations outside and inside homes on streets with high and low traffic volumes in Amsterdam (<3,000–30,974 veh/d). In this study, PPAH and VOCs were measured using methods based on gas chromatography. Fischer et al. found that while PM2.5 and PM10 mass concentrations were not specific indicators of traffic-related air pollution, PPAH and VOC levels were ~2-fold higher both indoor and outdoor in high traffic areas compared to low traffic areas. Roorda-Knape et al [14] measured PM2.5, PM10, black smoke (which is similar to BC), NO2, and benzene in residential areas <300 m from highways (80,000–152,000 veh/d) in the Netherlands. Black smoke was measured by a reflectance-based method using filtered particles; benzene was measured using a method based on gas chromatography. Roorda-Knape et al reported that outdoor concentrations of black smoke and NO2 decreased with distance from highways, while PM2.5, PM10, and benzene concentrations did not change with distance. In addition, Roorda-Knape et al. found that indoor black smoke concentrations were correlated with truck traffic, and NO2 was correlated with both traffic volume and distance from highways. Janssen et al. [15] studied PM2.5, PM10, benzene, and black smoke in 24 schools in the Netherlands and found that PM2.5 and black smoke increased with truck traffic and decreased with distance from highways (40,000–170,000 veh/d).

In summary, the literature shows that UFP, BC, CO and NOx are elevated near highways (>30,000 veh/d), and that other pollutants including VOCs and PPAHs may also be elevated. Thus, people living within about 30 m of highways are likely to receive much higher exposure to traffic-related air pollutants compared to residents living >200 m (+/- 50 m) from highways.

Cardiovascular health and traffic-related pollution

Results from clinical, epidemiological, and animal studies are converging to indicate that short-term and long-term exposures to traffic-related pollution, especially particulates, have adverse cardiovascular effects [16–18]. Most of these studies have focused on, and/or demonstrated the strongest associations between cardiovascular health outcomes and particulates by weight or number concentrations [19–21] though CO, SO2, NO2, and BC have also been examined. BC has been shown to be associated with decreases in heart rate variability (HRV) [22, 23] and black smoke and NO2 shown to be associated with cardiopulmonary mortality [24].

Short-term exposure to fine particulate pollution exacerbates existing pulmonary and cardiovascular disease and long-term repeated exposures increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and death [25, 26].

Though not focused on near-highway pollution, two large prospective cohort studies, the Six-Cities Study [27] and the American Cancer Society (ACS) Study [28] provided the groundwork for later research on fine particulates and cardiovascular disease. Both of these studies found associations between increased levels of exposure to ambient PM and sulfate air pollution recorded at central city monitors and annual average mortality from cardiopulmonary disease, which at the time combined cardiovascular and pulmonary disease other than lung cancer. The Six-Cities Study examined PM2.5 and PM10/15. The ACS study examined PM 2.5. Relative risk ratios of mortality from cardiopulmonary disease comparing locations with the highest and lowest fine particle concentrations (which had differences of 24.5 and 18.6 ug/m3 respectively) were 1.37 (1.11, 1.68) and 1.31 (1.17, 1.46) in the Six Cities and ACS studies, respectively. These analyses controlled for many confounders, including smoking and gas stoves but not other housing conditions or time spent at home. The studies were subject to intensive replication, validation, and reanalysis that confirmed the original findings. PM2.5 generally declined following implementation of new US Environmental Protection Agency standards in 1997 [17, 29], yet since that time studies have shown elevated health risks due to long-term exposures to the 1997 PM threshold concentrations [29, 30].

Much of the epidemiological research has focused on assessing the early physiological responses to short-term fluctuations in air pollution in order to understand how these exposures may alter cardiovascular risk profiles and exacerbate cardiovascular disease [31]. Heart rate variability, a risk factor for future cardiovascular outcomes, is altered by traffic-related pollutants particularly in older people and people with heart disease [22, 23, 32]. With decreased heart rate variability as the adverse outcome, negative associations between HRV and particulates were strongest for the smallest size fraction studied [33] (PM0.3–1.0); [34] (PM0.02–1). In two studies that included other pollutants, black carbon, an indicator of traffic particles, also elicited a strong association with both time and frequency domain HRV variables; associations were also strong for PM2.5 for both time and frequency HRV variables in the Adar et al study [[23]; this and subsequent near highway studies are summarized in Table 2], however, PM2.5 was not associated with frequency domain variables in the Schwartz et al. study [22].

Several studies show that exposure to PM varies spatially within a city [35–37], and finer spatial analyses show higher risks to individuals living in close proximity to heavily trafficked roads [18, 37]. A 2007 paper from the Woman's' Health Initiative used data from 573 PM2.5 monitors to follow over 65,000 women prospectively. They reported very high hazard ratios for cardiovascular events (1.76; 95% CI, 1.25 to 2.47) possibly due to the fine grain of exposure monitoring [18]. In contrast, studies that relied on central monitors [27, 28] or interpolations from central monitors to highways are prone to exposure misclassification because individuals living close to highways will have a higher exposure than the general area. A possible concern with this interpretation is that social gradients may also situate poorer neighborhoods with potentially more susceptible populations closer to highways [38–40].

At a finer grain, Hoek et al. [24] estimated home exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and black smoke for about 5,000 participants in the Netherlands Cohort Study on Diet and Cancer. Modeled exposure took into consideration proximity to freeways and main roads (100 m and 50 m, respectively). Cardiopulmonary mortality was associated with both modeled levels of pollutants and living near a major road with associations less strong for background levels of both pollutants. A case-control study [41], found a 5% increase in acute myocardial infarction associated with living within 100 m of major roadways. A recent analysis of cohort data found that traffic density was a predictor of mortality more so than was ambient air pollution [42]. There is a need for studies that assess exposure at these scales, e.g., immediate vicinity of highways, to test whether cardiac risk increases still more at even smaller scales.

Although we cannot review it in full here, we note that evidence beyond the epidemiological literature support the contention that PM2.5 and UFP (a sub-fraction of PM2.5) have adverse cardiovascular effects [16, 17]. PM2.5 appears to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease via mechanisms that likely include pulmonary and systemic inflammation, accelerated atherosclerosis and altered cardiac autonomic function [17, 22, 43–46]. Uptake of particles or particle constituents in the blood can affect the autonomic control of the heart and circulatory system. Black smoke, a large proportion of which is derived from mobile source emissions [30], has a high pulmonary deposition efficiency, and due to their surface area-to-volume ratios can carry relatively more adsorbed and condensed toxic air pollutants (e.g., PPAH) compared to larger particles [17, 47, 48]. Based on high particle numbers, high lung deposition efficiency and surface chemistry, UFP may provide a greater potential than PM2.5 for inducing inflammation [10]. UFPs have high cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity, through which numerous inflammatory responses are induced, compared to other particles [10]. Chronically elevated UFP levels such as those to which residents living near heavily trafficked roadways are likely exposed can lead to long-term or repeated increases in systemic inflammation that promote arteriosclerosis [18, 29, 34, 37].

Asthma and highway exposures

Evidence that near highway exposures present elevated risk is relatively well developed with respect to child asthma studies. These studies have evolved over time with the use of different methodologies. Studies that used larger geographic frames and/or overall traffic in the vicinity of the home or school [49–52] or that used self-report of traffic intensity [53] found no association with asthma prevalence. Most recent child asthma studies have, instead, used increasingly narrow definitions of proximity to traffic, including air monitoring or modeling) and have focused on major highways instead of street traffic [54–59]. All of these studies have found statistically significant associations between the prevalence of asthma or wheezing and living very close to high volume vehicle roadways. Confounders considered included housing conditions (pests, pets, gas stoves, water damage), exposure to tobacco smoke, various measures of socioeconomic status (SES), age, sex, and atopy, albeit self-reported and not all in a single study.

Multiple studies have found girls to be at greater risk than boys for asthma resulting from highway exposure [55, 57, 60]. A recent study also reports elevated risk only for children who moved next to the highway before they were 2 years of age, suggesting that early childhood exposure may be key [57]. The combined evidence suggests that living within 100 meters of major highways is a risk factor, although smaller distances may also result in graded increases in risk. The neglect of wind direction and the absence of air monitoring from some studies are notable missing factors. Additionally, recent concerns have been raised that geocoding (attaching a physical location to addresses) could introduce bias due to inaccuracy in locations [61].

Studies that rely on general area monitoring of ambient pollution and assess regional pollution on a scale orders of magnitude greater than the near-roadway gradients have also found associations between traffic generated pollution (CO and NOx) and prevalence of asthma [62] or hospital admission for asthma [63]. Lweguga-Mukasa et al. [64] monitored air up and down wind of a major motor vehicle bridge complex in Buffalo, NY and found that UFP were higher downwind, dropping off with distance. Their statistical models did not, however, support an association of UFP with asthma. A study in the San Francisco Bay Area measured PM2.5, BC and NOX over several months next to schools and found both higher pollution levels downwind from highways and a linear association of BC with asthma in long-term residents [60].

Gauderman et al. [65] measured NO2 next to homes of 208 children. They found an odds ratio (OR) of 1.83 (confidence interval (CI): 1.04–3.22) for outdoor NO2 (probably a surrogate for total highway pollution) and lifetime diagnosis of asthma. They also found a similar association with distance from residence to freeway. Self-report was used to control for numerous confounders, including tobacco smoke, SES, gas stoves, mildew, water damage, cockroaches and pets which did not substantially affect the association. Gauderman's study suggests that ambient air monitoring at the residence substantially increases statistical power to detect association of asthma with highway exposures.

Modeling of elemental carbon attributable to traffic near roadways based on ambient air monitoring of PM2.5 has recently emerged as a viable approach and a study using this method found an association with infant wheezing. The modeled values appear to be better predictors than proximity. Elevation of the residence relative to traffic was also an important factor in this study [66]. A 2007 paper reported on modeled NO2, PM2.5 and soot and the association of these values with asthma and various respiratory symptoms in the Netherlands [67]. While finding modest statistically significant associations for asthma and symptoms, it is somewhat surprising that they found stronger associations for development of sensitization to food allergens.

Pediatric lung function and traffic-related air pollution

Studies of association of children's lung function with traffic pollutants have used a variety of measures of exposure, including: traffic density, distance to roadways, area (city) monitors, monitoring at the home or school and personal monitoring. Studies have assessed both chronic effects on lung development and acute effects and have been both cross-sectional and longitudinal. The wide range of approaches somewhat complicates evaluation of the literature.

Traffic density in school districts in Munich was associated with decreases in forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1/FVC and other measures, although the 2-kilometer (km) areas, the use of sitting position for spirometry and problems with translation for non-German children were limitations [68]. Brunekreef et al. [69] used distance from major roadways, considered wind direction and measured black smoke and NO2 inside schools. They found the largest decrements in lung function in girls living within 300 m of the roadways.

A longitudinal study of children (average age at start = 10 years) in Southern California reported results at 4 [70] and 8 years [71]. Multiple air pollutants were measured at sites in 12 communities. Due to substantial attrition, only 42% of children enrolled at the start were available for the 8-year follow-up. Substantially lower growth in FEV1 was associated with PM10, NO2, PM2.5, acid vapor and elemental carbon at 4 and at 8 years. The analysis could not indicate whether the effects seen were reversible or not [72]. In 2007, it was reported from this same cohort that living within 500 m of a freeway was reported to be associated with reduced lung function [73].

A Dutch study [74] measured PM2.5, NO2, benzene and EC for one year at 24 schools located within 400 m of major roadways. While associations were seen between symptoms and truck traffic and measured pollutants, there was no significant association between any of the environmental measures and FVC < 85% or FEV1 < 85%. Restricting the analysis to children living within 500 m of highways generally increased ORs.

Personal exposure monitoring of NO2 as a surrogate for total traffic pollutants with 298 Korean college students found statistically significant associations with FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and forced expiratory volume between 25 and 75% (FEV25–75), but not with FVC. The multivariate regression model presented suggests that FEV25–75 was the outcome measure that most clearly showed an effect [75]. Cross-sectional studies of children in Korea [76] and France [77] also indicate that lung function is diminished in association with area pollutants that largely derive from traffic.

Time series studies suggest there are also acute effects. A study of 19 asthmatic children measured PM via personally carried monitors, at homes and at central site monitors. The study found deficits in FEV1 that were associated with PM, although many sources besides traffic contributed to exposure. In addition, the results suggest that ability to see associations with health outcomes improves at finer scale of monitoring [78]. PM was associated with reduced FEV1 and FVC in only the asthmatic subset of children in a Seattle study [79]. Studies have also seen associations between PM and self reported peak flow measurements [80, 81] and asthmatic symptoms [82].

Cancer and near highway exposures

As noted above, both the Six-Cities Study [27] and the American Cancer Society (ACS) Study [28] found associations between PM and lung cancer. Follow-up studies using the ACS cohort [29, 37] and the Six-Studies cohort [83] that controlled for smoking and other risk factors also demonstrated significant associations between PM and lung cancer. The original studies were subject to intensive replication, validation, and re-analysis which confirmed the original findings [84].

The ASHMOG study [85] was designed to look specifically at lung cancer and air pollution among Seventh-day Adventists in California, taking advantage of their low smoking rates. Air pollution was interpolated to centroids of zip codes from ambient air monitoring stations. Highway proximity was not considered. The study found associations with ozone (its primary pollutant of consideration), PM10 and SO2. Notably, these are not the pollutants that would be expected to be substantially elevated immediately adjacent to highways.

A case control study of residents of Stockholm, Sweden modeled traffic-related NO2 levels at their homes over 30 years and found that the strongest association involved a 20 year latency period [86]. Another case control study drawn from the European Prospective Investigation on Cancer and Nutrition found statistically significantly elevated ORs for lung cancer with proximity to heavy traffic (>10,000 cars per day) as well as for NO2 and PM10 at nearby ambient monitoring stations [87]. Nafstad et al. [88] used modeled NO2 and SO2 concentrations at the homes of over 16,000 men in Oslo to test associations with lung cancer incidence. The models included traffic and point sources. The study found small, but statistically significant associations between NO2 and lung cancer. Problems that run through all these studies are weak measures of exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke, the use of main roads rather than highways as the exposure group and modeled rather than measured air pollutants.

A study of regional pollution in Japan and a case control study of more localized pollution in a town in Italy also found associations between NO2 and lung cancer and PM and lung cancer [89, 90]. On the other hand, a study that calculated SIRs for specific cancers across lower and higher traffic intensity found little evidence of an association with a range of cancers [91].

The plausibility of near-highway pollution causing lung cancer is bolstered by the presence of known carcinogens in diesel PM. The US EPA has concluded after reviewing the literature that diesel exhaust is "likely to be carcinogenic to humans by inhalation" [92]. An interesting study of UFP and DNA damage adds credibility to an association with cancer [93]. This study had participants bicycle in traffic in Copenhagen and measured personal exposure to UFP and DNA oxidation and strand breaks in mononuclear blood cells. Bicycling in traffic increased UFP exposure and oxidative damage to DNA, thus demonstrating an association between DNA damage and UFP exposure in vivo.

Policy and research recommendations

Based on the literature reviewed above it is plausible that gradients of pollutants next to highways carry elevated health risks that may be larger than the risks of general area ambient pollutants. While the evidence is considerable, it is not overwhelming and is weak in some areas. The strongest evidence comes from studies of development of asthma and reduction of lung function during childhood, while the studies of cardiac health risk require extrapolation from area studies of smaller and larger geographic scales and inference from toxicology laboratory investigations. The lung cancer studies, because they include pollutants such as O3 that are not locally concentrated, are not particularly strong in terms of the case for near-highway risk. There is a need for lung cancer research that uses major highways rather than heavily trafficked roads as the environmental exposure.

While more studies of asthma and lung function in children are needed to confirm existing findings, especially studies that integrate exposure at school, home and during commuting, to refine our knowledge about the association, we would point to the greater need for studies of cardiac health and lung cancer and their association with near highway exposures as the primary research areas needing to be developed. Many of the studies of PM and cardiac or pulmonary health have focused on mortality. Near highway mortality studies may be possible, but would be lengthy if they were initiated as prospective cohorts. Other possibilities include retrospective case control studies of mortality, cross sectional studies or prospective studies that have end points short of mortality, such as biological markers of disease. For all health end points there is a need for studies that adequately address the possible confounding of SES with proximity to highways. There is good reason to think that property values decline near highways and that control for SES by, for example, income, may be inadequate.

Because of the incomplete development of the science regarding the health risks of near highway exposures and the high cost and implication of at least some possible changes in planning and development, policy decisions are complicated. The State of California has largely prohibited siting of schools within 500 feet of freeways (SB 352; approved by the governor October 2, 2003). Perhaps this is a viable model for other states or for national-level response. As it is the only such law of which we are aware, there may be other approaches that will be and should be tried. One limitation of the California approach is that it does nothing to address the population already exposed at schools currently cited near freeways and does not address residence near freeways.

Conclusion

The most susceptible (and overlooked) population in the US subject to serious health effects from air pollution may be those who live very near major regional transportation route, especially highways. Policies that have been technology based and regional in orientation do not efficiently address the very large exposure and health gradients suffered by these populations. This is problematic because even regions that EPA has deemed to be in regional PM "attainment" still include very large numbers of near highway residents who currently are not protected. There is a need for more research, but also a need to begin to explore policy options that would protect the exposed population.

Abbreviations

- UFP:

-

ultra fine particles

- BC:

-

black carbon

- NO2 :

-

nitrogen dioxide

- NOx:

-

oxides of nitrogen

- CO:

-

carbon monoxide

- PM:

-

particulate matter

- PM2.5 :

-

particulate matter less than 2.5 um

- PM10 :

-

particulate matter less than 10 um

- PPAH:

-

particle bound polyaromatic hydrocarbons

- EC:

-

elemental carbon

- VOC:

-

volatile organic compounds

- SO2 :

-

sulfur dioxide

- ACS:

-

American Cancer Society

- SES:

-

socioeconomic status

- EPA:

-

Environmental Protection Agency

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- FEV1 :

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FEV1/FVC:

-

ratio of FEV1 and forced vital capacity

- FEV25–75 :

-

forced expiratory volume between 25 and 75

- FVC:

-

forced vital capacity

- ug/m3 :

-

micrograms per cubic meter of air

- m:

-

meters

- um:

-

micrometers

- veh/d:

-

vehicles per day

- veh/h:

-

vehicles per hour

References

American Housing Survey for the United States: 2003 Series H150/03. Accessed May 2007., [http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/ahs/ahs03/ahs03.html]

2004, Massachusetts Fact Book

Chambers LA: Classification and extent of air pollution problems. Air Pollution. Edited by: Stern AC. 1976, Academic Press, NY, I: 3

Rogge WF, Hildemann LM, Mazurek MA, Cass GR, Simoneit BRT: Sources of fine organic aerosol. 2. Noncatalyst and catalyst-equipped automobiles and heavy-duty diesel trucks. Environmental Science Technology. 1993, 27: 636-651. 10.1021/es00041a007.

Graedel TE, Hawkins DT, Claxton LD: Atmospheric Chemical Compounds: Sources, Occurrence, and Bioassay. 1986, Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY

Shi JP, Khan AA, Harrison RM: Measurements of ultrafine particle concentration and size distribution in the urban atmosphere. The Science of the Total Environment. 1999, 235: 51-64. 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00189-8.

Zhu Y, Hinds WC, Kim S, Sioutas C: Concentration and size distribution of ultrafine particles near a major highway. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association. 2002, 52 (9): 1032-1042.

Zhu Y, Hinds WC, Kim S, Shen S, Sioutas C: Study of ultrafine particles near a major highway with heavy-duty diesel traffic. Atmospheric Environment. 2002, 36: 4323-4335. 10.1016/S1352-2310(02)00354-0.

Zhang KM, Wexler AS, Zhu Y, Hinds WC, Sioutas C: Evolution of particle number distribution near roadways. Part II: the 'Road-to-Ambient' process. Atmospheric Environment. 2004, 38: 6655-6665. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.06.044.

Sioutas C, Delfino RJ, Singh M: Exposure assessment for atmospheric ultrafine particles (UFP) and implications in epidemiologic research. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005, 113 (8): 947-955.

Hitchins J, Morawska L, Wolff R, Gilbert D: Concentrations of submicrometre particles from vehicle emissions near a major road. Atmospheric Environment. 2000, 34: 51-59. 10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00304-0.

Morawska L, Thomas S, Gilbert D, Greenaway C, Rijnders E: A study of the horizontal and vertical profile of submicrometer particulates in relation to a busy road. Atmospheric Environment. 1999, 33: 1261-1274. 10.1016/S1352-2310(98)00266-0.

Fischer PH, Hoek G, van Reeuwijk H, Briggs DJ, Lebret E, van Wijnen JH, Kingham S, Elliott PE: Traffic-related differences in outdoor and indoor concentrations of particles and volatile organic compounds in Amsterdam. Atmospheric Environment. 2000, 34: 3713-3722. 10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00067-4.

Roorda-Knape MC, Janssen NAH, De Hartog JJ, van Vliet PHN, Harssema H, Brunekreef B: Air pollution from traffic in city districts near major motorways. Atmospheric Environment. 1998, 32: 1921-1930. 10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00496-2.

Janssen NAH, van Vliet PHN, Aarts F, Harssema H, Brunekreef B: Assessment of exposure to traffic related air pollution of children attending schools near motorways. Atmospheric Environment. 2001, 35: 3875-3884. 10.1016/S1352-2310(01)00144-3.

National Research Council, Committee on Research Priorities for Airborne Particulate Matter: Research priorities for airborne particulate matter, IV: continuing research progress. 2004, National Academy Press, Washington, DC

US Environmental Protection Agency: Air quality criteria for particulate matter. 2004, Research Triangle Park

Miller KA, Siscovick DS, Sheppard L, Shepherd K, Sullivan JH, Anderson GL, Kaufman JD: Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007, 356: 447-458. 10.1056/NEJMoa054409.

Riedliker M, Cascio WE, Griggs TR, Herbst MC, Bromberg PA, Neas L, Williams RW, Devlin RB: Particulate matter exposure in cars is associated with cardiovascular effects in healthy young men. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004, 169: 934-940. 10.1164/rccm.200310-1463OC.

Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Stang A, Beck E, Dragano N, Möhlenkamp S, Schmermund A, Memmesheimer M, Mann K, Erbel R, Jockel KH, Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study Investigative Group: Residence close to high traffic and prevalence of coronary heart disease. European Heart Journal. 2006, 27: 2696-2702. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl278.

Ruckerl R, Greven S, Ljungman P, Aalto P, Antoniades C, Bellander T, Berglind N, Chrysohoou C, Forastiere F, Jacquemin B, von Klot S, Koenig W, Kuchenhoff H, Lanki T, Pekkanen J, Perucci CA, Schneider A, Sunyer J, Peters A: Air pollution and inflammation (IL-6, CRP, fibrinogen) in myocardial infarction survivors. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007, 115: 1072-1080.

Schwartz J, Litonjua A, Suh H, Verrier M, Zanobetti A, Syring M, Nearing B, Verrier R, Stone P, MacCallum G, Speizer FE, Gold DR: Traffic related pollution and heart rate variability in a panel of elderly subjects. Thorax. 2005, 60: 455-461. 10.1136/thx.2004.024836.

Adar SD, Gold DR, Coull BA, Schwartz J, Stone P, Suh H: Focused exposures to airborne traffic particles and heart rate variability in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2007, 18: 95-103. 10.1097/01.ede.0000249409.81050.46.

Hoek G, Brunekreek B, Goldbohm S, Fischer P, van den Brandt PA: Association between mortality and indicators of traffic-related air pollution in the Netherlands: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2002, 360: 1203-1209. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11280-3.

Peters A, von Klot S, Heier M, Trentinaglia I, Hormann A, Wichmann HE, Lowel H: Exposure to traffic and the onset of myocardial infarction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004, 351: 1861-70. 10.1056/NEJMoa040203.

Pope CA, Dockery DW: Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. Journal of Air and Waste Management. 2006, 56 (6): 709-742.

Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG, Speizer FE: An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993, 329: 1753-9. 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401.

Pope CA, Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Dockery DW, Evans JS, Speizer FE, Hath CW: Particulate air pollution as a predictor of mortality in a prospective study of US adults. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995, 151: 669-674.

Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, Thurston GD: Lung Cancer, Cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002, 287: 1132-1141. 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132.

Kunzli N, Jerrett M, Mack WJ, Beckerman B, LaBree L, Gilliland F, Thomas D, Peters J, Hodis HN: Ambient air pollution and Atherosclerosis in Los Angeles. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005, 113: 201-206.

Peters A: Particulate matter and heart disease: Evidence from epidemiological studies. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2005, 477-482. 10.1016/j.taap.2005.04.030. Suppl 2

Wheeler A, Zanobetti A, Gold DR, Schwartz J, Stone P, Suh H: The relationship between ambient air pollution and heart rate variability differs for individuals with heart and pulmonary disease. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006, 114: 560-566.

Chuang K, Chan C, Chen N, Su T, Lin L: Effects of particle size fractions on reducing heart rate variability in cardiac and hypertensive patients. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005, 113: 1693-1697.

Chan C, Chuang K, Shiao G, Lin L: Personal exposure to submicrometer particles and heart rate variability in human subjects. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004, 112: 1063-1067.

Brauer M, Hoek G, van Vliet P, Meliefste K, Fischer P, Gehring U, Heinrich J, Cyrys J, Bellander T, Lewne M, Brunekreef B: Estimating long-term average particulate air pollution concentrations: application of traffic indicators and geographic information systems. Epidemiology. 2003, 14: 228-239. 10.1097/00001648-200303000-00019.

Brunekreef B, Holgate ST: Air pollution and health. Lancet. 2002, 360: 1233-1242. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8.

Jerrett M, Finkelstein M: Geographies of risk in studies linking chronic air pollution exposure to health outcomes. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 2005, 68: 1207-1242. 10.1080/15287390590936085.

O'Neill MS, Jerrett M, Kawachi I, Levy JI, Cohen AJ, Gouveia N, Wilkinson P, Fletcher T, Cifuentes L, Schwartz J: Workshop on Air Pollution and Socioeconomic Conditions. Health, wealth, and air pollution: advancing theory and methods. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003, 111: 1861-1870.

Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Pope CA, Krewski D, Newbold KB, Thurston G, Shi Y, Finkelstein N, Calle EE, Thun MJ: Spatial Analysis of Air Pollution and Mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology. 2005, 16 (6): 727-736. 10.1097/01.ede.0000181630.15826.7d.

Finkelstein M, Jerrett M, Sears MR: Environmental inequality and circulatory disease mortality gradients. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005, 59: 481-487. 10.1136/jech.2004.026203.

Tonne C, Melly S, Mittleman M, Coull B, Goldberg R, Schwartz J: A case-control analysis of exposure to traffic and acute myocardial infarction. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007, 115: 53-57.

Lipfert FW, Wyzga RE, Baty JD, Miller JP: Traffic density as a surrogate measure of environmental exposures in studies of air pollution health effects: Long-term mortality in a cohort of US veterans. Atmospheric Environment. 2006, 40: 154-169. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.09.027.

Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thurston GD, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Godleski JJ: Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution – Epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 2004, 109: 71-77. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F.

Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith SC, Tager I: Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004, 109: 2655-2671. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8.

Sun Q, Wang A, Jin X, Natanzon A, Duquaine D, Brook RD, Aguinaldo JG, Fayad Z, Fuster V, Lippman M, Chen LC, Rajagopalan S: Long-term air pollution exposure and acceleration of atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation in an animal model. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005, 294: 3003-3010. 10.1001/jama.294.23.3003.

Sandhu RS, Petroni DH, George WJ: Ambient particulate matter, C-reactive protein, and coronary artery disease. Inhalation Toxicology. 2005, 17: 409-413. 10.1080/08958370590929538.

Oberdorster G: Pulmonary effects of inhaled ultrafine particles. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2001, 65: 1531-1543.

Delfino RJ, Sioutas C, Malik S: Potential role of ultrafine particles in associations between airborne particle mass and cardiovascular health. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005, 113: 934-946.

Venn A, Lewis S, Cooper M, Hubbard R, Hill I, Boddy R, Bell M, Britton J: Local road traffic activity and the prevalence, severity, and persistence of wheeze in school children: combined cross sectional and longitudinal study. Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2000, 57: 152-158. 10.1136/oem.57.3.152.

Waldron G, Pottle B, Dod J: Asthma and the motorways – One district's experience. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1995, 17: 85-89.

Lewis SA, Antoniak M, Venn AJ, et al.: Secondhand smoke, dietary fruit intake, road traffic exposures, and the prevalence of asthma: A cross-sectional study in young children. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005, 161: 406-411. 10.1093/aje/kwi059.

English P, Neutra R, Scalf R, Sullivan M, Waller L, Zhu L: Examining associations between childhood asthma and traffic flow using a geographic information system. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1999, 107: 761-767. 10.2307/3434663.

Heinrick J, Topp R, Gerring U, Thefeld W: Traffic at residential address, respiratory health, and atopy in adults; the National German Health Survey 1998. Environmental Research. 2005, 98: 240-249. 10.1016/j.envres.2004.08.004.

Van Vliet P, Knape M, de Hartog J, Janssen N, Harssema H, Brunekreef B: Motor vehicle exhaust and chronic respiratory symptoms in children living near freeways. Environmental Research. 1997, 74: 122-132. 10.1006/enrs.1997.3757.

Venn AJ, Lewis SA, Cooper M, Hubbard R, Britton J: Living near a main road and the risk of wheezing illness in children. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001, 164 (12): 2177-2180.

Venn A, Yemaneberhan H, Lewis S, Parry E, Britton J: Proximity of the home to roads and the risk of wheeze in an Ethiopian population. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2005, 62: 376-380. 10.1136/oem.2004.017228.

McConnell R, Berhane K, Yao L, Jerrett M, Lurmann F, Gilliland F, Kunzli N, Gauderman J, Avol E, Thomas D, Peters J: Traffic susceptibility, and childhood asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006, 114: 766-772.

Nicolai T, Carr D, Weiland SK, Duhme H, von Ehrenstein O, Wagner C, von Mutius E: Urban traffic and pollutant exposure related to respiratory outcomes and atopy in a large sample of children. European Respiratory Journal. 2003, 21: 956-963.

Ryan PH, LeMasters , Biswas P, Levin L, Hu S, Lindsey M, Bernstein DI, Lockey J, Villareal M, Hershey GKH, Grinshpun SA: A comparison of proximity and land use regression traffic exposure models and wheezing in infants. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007, 115: 278-284.

Kim JJ, Smorodinsky S, Lipsett M, Singer BC, Hodgson AT, Ostro B: Traffic-related air pollution near busy roads: The East Bay children's respiratory health study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004, 170: 520-526. 10.1164/rccm.200403-281OC.

Ong P, Graham M, Houston D: Policy and programmatic importance of spatial alignment of data sources. Am J Public Health. 2006, 96: 499-504. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071373.

Hwang BF, Lee YL, Lin YC, Jaakkola JJ, Guo YL: Traffic related air pollution as a determinant of asthma among Taiwanese school children. Thorax. 2005, 60: 467-473. 10.1136/thx.2004.033977.

Migliaretti G, Cadum E, Migliore E, et al.: Traffic air pollution and hospital admissions for asthma: A case control approach in a Turin (Italy) population. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2005, 78: 164-169. 10.1007/s00420-004-0569-3.

Lweguga-Mukasa JS, Oyana TJ, Johjnson C: Local ecological factors, ultrafine particulate concentrations, and asthma prevalence rates in Buffalo, New York, neighborhoods. Journal of Asthma. 2005, 42: 337-348.

Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Lurmann F, Kuenzli N, Gilliland F, Peters J, McConnell R: Childhood asthma and exposure to traffic and nitrogen dioxide. Epidemiology. 2005, 16: 737-743. 10.1097/01.ede.0000181308.51440.75.

Ryan PH, LeMasters GK, Biswas P, Levin L, Hu S, Lindsey M: A comparison of proximity and land use regression traffic exposure models and wheezing in infants. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007, 115: 278-284.

Brauer M, Hoek G, Smit HA, de Jongste JC, Gerritsen J, Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Brunekreef B: Air pollution and development of asthma, allergy and infections in a birth cohort. European Respiratory Journal. 2007, 29: 879-888. 10.1183/09031936.00083406.

Wjst M, Reitmeir P, Dodd S, Wulff A, Nicolai T, von Loeffelholz-Colberg EF, von Mutius E: Road traffic and adverse effects on respiratory health in children. British Medical Journal. 1993, 307: 596-307.

Brunekreef B, Janssen NA, de Hartog J, Harssema H, Knape M, van Vliet P: Air pollution from truck traffic and lung function in children living near motorways. Epidemiology. 1997, 8: 298-303. 10.1097/00001648-199705000-00012.

Gauderman WJ, McConnell , Gilliland F, London S, Thomas D, Avol E, Vora H, Berhane K, Rappaport EB, Lurmann F, Margolis HG, Peters J: Association between air pollution and lung function growth in Southern California Children. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000, 162 (4 Pt 1): 1383-1390.

Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Gilliland F, Vora H, Thomas D, Berhane K, McConnell R, Kuenzli N, Lurmann F, Rappaport E, Margolis H, Bates D, Peters J: The Effect of Air Pollution on Lung Development from 10 to 18 Years of Age. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005, 351: 1057-67. 10.1056/NEJMoa040610.

Merkus PJFM: Air pollution and lung function. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005, 351: 2652-

Gauderman WJ, Vora H, McConnell R, Berhane K, Gilliland F, Thomas D, Lurmann F, Avol E, Kunzli N, Jarrett M, Peters J: Effect of exposure to traffic on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age: A cohort study. The Lancet. 2007, 369: 571-577. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60037-3.

Janssen NA-H, Brunekreef B, van Vliet P, Aarts F, Meliefste K, Harssema H, Fischer P: The relationship between air pollution from heavy traffic and allergic sensitization, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and respiratory symptoms in Dutch school children. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003, 111: 1512-1518.

Hong Y-C, Leem J-H, Lee K-H, Park D-H, Jang J-Y, Kim S-T, Ha E-H: Exposure to air pollution and pulmonary function in university students. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2005, 78: 132-138. 10.1007/s00420-004-0554-x.

Kim HJ, Lim DH, Kim JK, Jeong SJ, Son BK: Effects of particulate matter (PM10) on pulmonary function of middle school children. Journal of the Korean Medical Society. 2005, 20 (1): 42-45.

Penard-Morand C, Charpin D, Raherison C, Kopferschmitt C, Caillaud D, Lavaud F, Annesi-Maesano I: Long-term exposure to background air pollution related to respiratory and allergic health in schoolchildren. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2005, 35: 1279-1287. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02336.x.

Delfino RJ, Quintana PJE, Floro J, Gastanaga VM, Samimi BS, Klienman MT, Liu LJ, Bufalino C, Wu C, McLaren CE: Association of FEV1 in asthmatic children with personal and microenvironment exposure to airborne particulate matter. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004, 112: 932-941.

Koenig JQ, Larson TV, Hanley QS, Rebolledo V, Dumler K, Checkoway H, Wang SZ, Lin D, Pierson WE: Pulmonary function changes in children associated with fine particulate matter. Environmental Research. 1993, 63: 26-38. 10.1006/enrs.1993.1123.

Van der Zee SC, Hoek G, Boezen HM, Schouten JP, van Wijnen JH, Brunekreef B: Acute effects of urban air pollution on respiratory health of children with and without chronic respiratory symptoms. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 1999, 56 (12): 802-813.

Pekkenen J, Timonen KL, Ruuskanen J, Reponen A, Mirme A: Effects of ultrafine and fine particulates in urban air on peak expiratory flow among children with asthmatic symptoms. Environmental Research. 1997, 74: 24-33. 10.1006/enrs.1997.3750.

Peters JM, Avol E, Navidi W, London SJ, Gauderman WJ, Lurmann F, Linn WS, Margolis H, Rappaport E, Gong H, Thomas DC: A study of twelve Southern California communities with differing levels and types of air pollution: Prevalence of respiratory morbidity. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999, 159 (3): 760-767.

Laden F, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, Dockery DE: Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard six-cities study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006, 173: 667-672. 10.1164/rccm.200503-443OC.

Health Effects Institute: Reanalysis of the Harvard six cities study and the American Cancer Society study of particulate air pollution mortality. Final Version; Boston, MA. 2000

Beeson WL, Abbey DE, Knutsen SF: Long-term concentrations of ambient air pollutants and incident lung cancer in California adults: Results from the ASHMOG study. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1998, 106: 813-823. 10.2307/3434125.

Nyberg F, Gustavsson P, Jarup L, Bellander T, Berglind N, Jakobsson R, Pershagen G: Urban air pollution and lung cancer in Stockholm. Epidemiology. 2000, 11: 487-495. 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00002.

Vineis P, Hoek G, Krzyzanowski M, Vigna-Tagliani F, Veglia F, Airoldi L, Autrup H, Dunning A, Garte S, Hainaut P, Malaveille C, Matullo G, Overvad K, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Clavel-Chapelon F, Linseisen J, Boeing H, Trichopoulou A, Palli D, Peluso M, Krogh V, Tumino R, Panico S, Bueno-De-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Lund EE, Gonzalez CA, Martinez C, Dorronsoro M, Barricarte A, Cirera L, Quiros JR, Berglund G, Forsberg B, Day NE, Key TJ, Saracci R, Kaaks R, Riboli E: Air pollution and risk of lung cancer in a prospective study in Europe. International Journal of Cancer. 2006, 119: 169-174. 10.1002/ijc.21801.

Nafstad P, Haheim LL, Oftedal B, Gram F, Holme I, Hjermann I, Leren P: Lung cancer and air pollution: A 27-year follow up of 16 209 Norwegian men. Thorax. 2003, 58: 1071-1076. 10.1136/thorax.58.12.1071.

Choi K-S, Inoue S, Shinozaki R: Air pollution, temperature, and regional differences in lung cancer mortality in Japan. Archives of Environmental Health. 1997, 52: 160-

Biggeri A, Barbone F, Lagazio C, Bovenzi M, Stanta G: Air pollution and lung cancer in Trieste, Italy: Spatial analysis of risk as a function of distance from sources. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1996, 104: 750-754. 10.2307/3433221.

Visser O, van Wijnen JH, van Leeuwen FE: Residential traffic density and cancer incidence in Amsterdam, 1989–1997. Cancer Causes & Control. 2004, 15: 331-339. 10.1023/B:CACO.0000027480.32494.a3.

US Environmental Protection Agency: Health Assessment Document for Diesel Engine Exhaust. Washington, DC. 2002

Vinzents PS, Meller P, Sorensen M, Knudsen LE, Hertel O, Jensen FP, et al.: Personal exposure to ultrafine particulates and oxidative DNA damage. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005, 113: 1485-1490.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wig Zamore for useful insights into the topic. The Jonathan M Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service partially supported the effort of Doug Brugge and Christine Rioux. Figure 1 was reproduced with permission of the publisher.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DB took the lead on the manuscript. He co-wrote the background and wrote the sections on asthma, lung function and cancer and the conclusions. JLD wrote the section on air pollutants near roadways and contributed substantially to the background. CR wrote the section on cardiovascular health. All authors participated in editing and refining the manuscript and all read it multiple times, including the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Brugge, D., Durant, J.L. & Rioux, C. Near-highway pollutants in motor vehicle exhaust: A review of epidemiologic evidence of cardiac and pulmonary health risks. Environ Health 6, 23 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-6-23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-6-23