Abstract

Background

It has been known that hypertension is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). CVD is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in developed and developing countries. Elevation of blood pressure (BP) increases the adverse effect for cardiovascular outcomes. Prevention of increased BP plays a crucial role in a reduction of those outcomes, leading to a decrease in mortality. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of dietary black sesame meal on BP and oxidative stress in individuals with prehypertension.

Methods

Twenty-two women and eight men (aged 49.8 ± 6.6 years) with prehypertension were randomly divided into two groups, 15 subjects per group. They ingested 2.52 g black sesame meal capsules or placebo capsules each day for 4 weeks. Blood samples were obtained after overnight fasting for measurement of plasma lipid, malondialdehyde (MDA) and vitamin E levels. Anthropometry, body composition and BP were measured before and after 4-week administration of black sesame meal or a placebo.

Results

The results showed that 4-week administration of black sesame meal significantly decreased systolic BP (129.3 ± 6.8 vs. 121.0 ± 9.0 mmHg, P < 0.05) and MDA level (1.8 ± 0.6 vs. 1.2 ± 0.6 μmol/L, P < 0.05), and increased vitamin E level (29.4 ± 6.0 vs. 38.2 ± 7.8 μmol/L, P < 0.01). In the black sesame meal group, the change in SBP tended to be positively related to the change in MDA (R = 0.50, P = 0.05), while the change in DBP was negatively related to the change in vitamin E (R = -0.55, P < 0.05). There were no correlations between changes in BP and oxidative stress in the control group.

Conclusions

These results suggest the possible antihypertensive effects of black sesame meal on improving antioxidant status and decreasing oxidant stress. These data may imply a beneficial effect of black sesame meal on prevention of CVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in developing countries. Elevation of blood pressure (BP) is a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including stroke, myocardial infarction, renal failure and death [1]. Prevention of increased BP therefore plays a crucial role in a reduction of those outcomes. Impaired balance between relaxing and contracting factors in the endothelium of blood vessels is an important pathogenic mechanism of hypertension. Increased pro-oxidant and decreased antioxidant activities have been shown to be some of the mechanisms of the pathogenesis of hypertension [2].

It has been reported that sesame seeds can improve oxidative stress due to actions of their contents of vitamin E and lignans including sesamin, sesamolin and sesamol [3–7]. Thus, sesame is likely to have potential health benefits in relation to CVD by its antihypertensive effects [8–11]. Although many previous studies have shown different effects of vitamin E on BP [12–14], these studies investigated the effect of supplementation of either alpha-tocopherol alone or mixed with gamma-tocopherol on BP in diabetic [12, 13] or hypertensive [14] patients who took antihypertensive drugs. Interactions between alpha-tocopherol and the drug may diminish the antihypertensive effect on BP [15]. Moreover, the dose of vitamin E in those previous studies may have been so high that it caused increased or unchanged effects on BP.

Interestingly, the antihypertensive effect of black sesame (Sesamum indicum Linn.) meal, a product of sesame oil manufacturing, does not seem to have been previously investigated. Positive results may provide additional value to the manufactured product. Since we wanted to examine preventive effects, we performed the research on pre-hypertensive [16] healthy individuals who did not take any medicine; hence the vitamin E could exercise its antioxidant activity without interference with any antihypertensive drug. Moreover, black sesame meal contains gamma-tocopherol which was reported to be lower in patients with coronary heart disease than control subjects [17]. Taken together with the safety dose of vitamin E in black sesame meal in this study [18], this may reveal an anti-hypertensive effect of black sesame meal.

Based on knowledge of the effects of sesame seed and lignans on oxidative stress, which is one of mechanisms of the pathogenesis of hypertension [2], it was hypothesized that black sesame meal may have an antihypertensive effect in pre-hypertensive humans via improving antioxidant status and decreasing oxidant stress. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effects of 4-week administration of black sesame meal on BP and oxidative stress in pre-hypertensive humans.

Methods

Study design

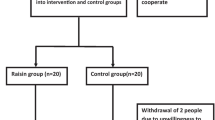

A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation was undertaken. Subjects were divided into two groups, with 11 men and 4 women in each group, matched by age, BMI and BP: a black sesame meal group (SG) (N = 15, aged 49.3 ± 7.7 years), and a placebo group (PG) (N = 15, aged 50.3 ± 5.6 years). Subjects and investigators were blinded as to the composition of the black sesame meal and placebo capsules. After being screened by physical and blood examination, all subjects were asked to complete health questionnaires in order to provide health information including cardiovascular risk factors. Subjects were seen on two visits: before and after 4-week administration of either black sesame meal capsules or placebo capsules. During the 4 weeks, subjects were asked to take 6 capsules each time, three times a day, with water after a meal. They were asked to avoid vitamins and other dietary supplements during the administration period. Subjects were instructed not to change their diet and exercise routine throughout the trial. At both visits, after a 12-h fasting period, blood samples were collected to measure blood parameters. Anthropometry (height, weight, and waist and hip circumferences), body composition and BP were also measured.

Subjects

Thirty middle-aged subjects (22 men and 8 women) were recruited from the general population, supported by an annual health checkup program performed at the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, during 2008-2009. Subjects had no other diseases except prehypertension as indicated either by systolic blood pressure (SBP) from 120 to 139 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) from 80 to 89 mmHg [16]. The patients were not currently taking any medication or dietary supplementation that affected BP. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University (HE 510254). Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects; verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Power calculation

A change in SBP after the ingestion of black sesame meal was used to calculate the sample size of this study [9]. The magnitude of the change in SBP was 5 mmHg for the power calculation. It was decided to require 90% power at a significance level of 0.05. Thus, having at least 15 subjects was required to finish this study.

Preparation of black sesame meal

The black sesame meal was prepared at the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand. The sesame seeds were roasted before being pressed. The remaining sesame meal was grounded into powder and mixed with an adsorbent. This process is the same as that used for commercial preparation. Each capsule of black sesame meal was formulated to contain 0.42 g of black sesame meal. The contents (mean ± SD) of carbohydrate, protein and fiber of the black sesame meal were 46.37%, 21.57% and 14.12%, respectively. Moreover, sesamin and sesamolin contents were 1.172 ± 0.002 mg/g DW and 0.605 ± 0.003 mg/g DW, respectively [19]. Total tocopherol was 105.41 ± 2.49 μg/g DW, mostly consisting of gamma-tocopherol (102.78 ± 2.46 μg/g DW); alpha-tocopherol was not detectable [19]. The placebo capsule contained the same contents, but without any black sesame meal. Both capsules were the same shape and color.

Measurement of BP

BP (mmHg) and heart rate (HR,/min) were measured in the morning, after a 20-min rest, using an automatic sphygmomanometer (Accurtorr 1A; Datascope, Japan) on the right upper arm while the subject was in a sitting position. Average BP and HR were calculated from three measurements after an almost stable BP seemed to have been reached. SBP and DBP were used to calculate mean arterial pressure (MAP) by the formula: MAP = DBP + 1/3 (SBP - DBP).

Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA)

A plasma lipid peroxidation marker, MDA, was estimated using thiobarbituric acid, as previously described [20]. In brief, 150 μl of plasma was reacted with 125 μl 10% trichloroacetic acid, 125 μl 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 125 μl 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 10 μl 0.5 μg/ml butylated hydroxytoluene. After vortexing vigorously for 30 s, the mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then 500 μl 0.6% thiobarbituric acid was added, and the mixture was heated at 95°C for 30 min. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer (Genesys 20, SN: 35 gk 130009; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). A standard curve was generated with appropriate concentrations of 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane standard (0.3-10 μmol/L); the plasma MDA concentration was expressed as μmol/L of plasma.

Measurement of vitamin E

Serum vitamin E was determined using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), according to the method of Thurnham [21], by injection into a reversed-phase C-18 Spherisorb ODS2 column (diameter 5 μm, 4.6 × 100 mm; Waters, USA). The mobile phase consisted of methanol/acetonitrile/dichloromethane at a ratio of 4:4:1 with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. A wavelength UV-visible detector (model 2847, Waters) was set at a wavelength of 292 nm for the detection of vitamin E. Quantification was based on peak-height measurement, using the Clarity 2.2.0.67 software program, version C22 (DataApex, Czech Republic).

Statistical analysis

All statistics were generated using Stata statistical software, version 10 (StataCorp, USA). Data were expressed as means ± SD. Changes in BP, MDA and vitamin E levels between groups were compared by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with adjustment for baseline values. The variables under study before and after the administration within groups were compared by Student's paired t-test. The relationships between changes in oxidative stress variables and BP were analyzed by Pearson's correlation. Statistical analyses were two-sided. If the statistical probability (P -value) was less than 0.05, the differences were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1. All subjects were pre-hypertensive individuals. No significant differences in age, anthropometry, body composition, and levels of MDA and vitamin E, SBP, DBP, MAP and HR were found between SG and PG groups.

In the SG group, after 4 weeks of administration of black sesame meal, SBP was significantly decreased when compared with before administration (121.0 ± 9.0 vs. 129.3 ± 6.8 mmHg, P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). Meanwhile, in the PG group, SBP was slightly decreased after the placebo administration when compared with before administration values (130.4 ± 4.8 vs. 130.6 ± 9.5 mmHg, P = 0.52). The decrease in SBP in the SG group was significantly greater than that in the PG group (P < 0.05) with adjustment for baseline values. There were no apparent side effects induced by black sesame meal throughout the study.

In the SG group, after 4 weeks of administration of black sesame meal, DBP was decreased when compared with before administration (72.8 ± 9.8 vs. 77.0 ± 7.4 mmHg, P = 0.20) (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, in the PG group (85.9 ± 12.1 vs. 80.6 ± 7.7 mmHg, P = 0.14), where the level was higher than before administration. However, the changes in DBP between groups with adjustment for baseline values were not significantly different.

Moreover, there was no significant difference in changes of average HR with adjustment for baseline values in both PG and SG subjects (66.8 ± 7.4 and 68.7 ± 9.1/min before and 71.2 ± 11.1 and 71.4 ± 6.4/min after 4-week administration of black sesame meal and placebo, P = 0.76).

Plasma MDA concentrations significantly decreased after the 4-week administration of black sesame meal when compared with before administration concentrations (1.2 ± 0.6 vs. 1.8 ± 0.6 μmol/L, P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in MDA concentrations, however, before and after 4-week administration of a placebo (1.8 ± 0.5 vs. 1.9 ± 0.6 μmol/L, P = NS). When compared with the PG subjects, the SG subjects had significantly lower plasma MDA concentrations after the 4-week administration with adjustment for baseline values (1.8 ± 0.5 (PG), 1.2 ± 0.6 (SG) μmol/L, P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

As shown in Figure 3, plasma vitamin E (total tocopherol) concentrations after 4-week administration of black sesame meal were significantly increased when compared with before administration concentrations (38.2 ± 7.8 vs. 29.4 ± 6.0 μmol/L, P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in vitamin E concentrations before and after 4-week administration of the placebo (29.8 ± 6.0 vs. 26.5 ± 5.5 μmol/L, P = NS). When compared with the PG group, the SG group had significantly greater plasma vitamin E concentrations after 4-week of administration with adjustment for baseline values (29.8 ± 6.0 (PG), 38.2 ± 7.8 (SG) μmol/L, P < 0.01).

Only in the black sesame meal group did the change in SBP tend to be positively related to the change in MDA concentration (R = 0.50, P = 0.05), while the change in DBP was negatively related to the change in vitamin E concentration (R = 0.55, P < 0.05). There were no significant correlations between changes in BP and oxidative stress indicators in the placebo group.

Discussion

This study appears to be the first to reveal the possible antihypertensive effects of black sesame meal in participants with prehypertension. The results demonstrated that after matching for age, BMI and BP, 4-week daily administration of 2.52 g black sesame meal caused a significant reduction in SBP, by an average of 8.2 mmHg.

Interestingly, the INTERSALT study revealed that a reduction of 2 to 3 mmHg of SBP was associated with a 4% decrease in mortality from CVD in the USA and UK [22] and a 6.4% decrease in mortality from cerebral vascular disease in Japan [1]. Based on these longer term studies, if the present reduction in BP with sesame meal (8.2 mmHg) was sustained in the long term, this could reduce the risk of CVD and stroke by 16.4% and 26.2% respectively. This study shows that the ingestion of black sesame meal may have a potential effect on reduction in mortality from CVD and stroke.

Although no previous study has directly investigated the effect of black sesame meal on BP, many studies have reported the potential antihypertensive effect of sesame's contents (i.e. lignan and vitamin E) in humans and rats [8–11, 23]. However, this is inconsistent with many other previous studies which reported different results [12–14]. Some previous studies have reported that supplementation of either alpha-tocopherol alone or mixed with gamma-tocopherol increased [12] or did not change [13] BP in diabetic or treated hypertensive patients [14]. This may be attributed to an interference of alpha-tocopherol and the antihypertensive drug taken by some subjects in previous studies; whereas subjects in this study were healthy and did not take any antihypertensive drug. Moreover, the dose of vitamin E in those previous studies may have been so high that it caused increased or unchanged effects on BP.

A possible mechanism responsible for the antihypertensive effect of black sesame meal in this study may be an improved balance between relaxing and contracting factors in the endothelium of blood vessels. In this study, black sesame meal may have enhanced the relaxing factor, resulting in improved endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in the pre-hypertensive participants relating to oxidative stress. The antihypertensive effect of sesamin, in mildly hypertensive humans was supported by a previous study [9]. The authors reported that the ingestion of 60 g of sesamin per day for 4 weeks decreased SBP by an average of 3.5 mmHg, and DBP by 1.9 mmHg [9]. Moreover, the increased plasma vitamin E in this study may be due to the increased vitamin E or the inhibition of catabolism of vitamin E. In addition, bioavailability of vitamin E may be increased by interactions between sesame lignan and tocopherols [24]. The accumulation of vitamin E acts by detoxifying the hydroxyl and proxy radicals, leading to reduced lipid peroxidation, or by reducing excess tissue aldehydes [11]. This is supported by many previous studies, in which supplementation of either vitamin E or sesamin and sesamolin demonstrated that these antioxidants inhibit lipid peroxidation [3–7, 25]. The antioxidant effect is likely to contribute to the decreased endothelial dysfunction from free radicals [26], resulting in an increase in the vasorelaxing factor, nitric oxide (NO) [27].

However, a mechanism that is not relevant to oxidative stress cannot be ruled out. This was supported by a study by Ward et al. (2004) which failed to show a link between oxidative stress and BP [28]. It was shown that gamma-tocopherol supplementation increased protein expression of nitric oxide synthase [29], which stimulates vasorelaxation. Moreover, the potential effect of vitamin E on membrane fluidity is likely to be another mechanism of antihypertension. In vitro study, vitamin E was shown to preserve endothelial cell (EC) migration in oxidized low-density lipoprotein cells (oxLDL) and restore the endothelial monolayer after injury by inhibiting changes in membrane integrity caused by oxLDL [30]. A previous study in rats demonstrated that antihypertensive rats had lower BP than normotensive rats due to reduced membrane fluidity after ingestion of vitamin E 3 d/week for 3 weeks [31]. These non-antioxidant properties of vitamin E could be important in the prevention of atherosclerosis, resulting in a reduction in BP in humans. Sesamin supplementation also induced NO and inhibited endothelin-1 production by EC [32]. These findings indicate an improved ability of the endothelium to relax. In addition, a recent study has shown that sesamin inhibited some CYP450 enzymes and the production of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE), which might influence BP independently of any effects on oxidative stress [33]. Moreover, sesamin increased Ca2+ antagonistic vasorelaxing activity [34]. It should be emphasized in this discussion that these hypotheses are only on the basis of the decrease in MDA and increased vitamin E, because other possible mechanisms were not measured.

A limitation of this study is a lack of data on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation determined by NO and other antioxidants such as vitamin C. Moreover, the potential effect of vitamin E on membrane fluidity and the ability of sesame lignans to inhibit 20-HETE synthesis in human renal and liver microsomes were not investigated by this study. Thus, further investigation of these variables explaining the mechanisms of black sesame meal on prevention of hypertension is needed. Importantly, having no discernible side effects from the ingestion of black sesame meal throughout this study implies that it may be safe as a nutritional supplement for health promotion.

Conclusions

This study suggests a beneficial effect of dietary black sesame meal on a reduction in blood pressure in pre-hypertensive humans. It is likely that the antihypertensive effect is due to decreased oxidative stress. Taken together with the absence of side effects and inexpensive preparation, the regular ingestion of dietary black sesame meal may be beneficial for CVD prevention in individuals with prehypertension, or even those with hypertension. A future study that investigates this advantageous effect is suggested.

References

Japanese Society of Hypertension: Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2004). Hypertens Res. 2006, 29 (Suppl): S1-S105. 10.1291/hypres.29.S1.

Dhalla NS, Temsah RM, Netticadan T: Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J Hypertens. 2000, 18: 655-673. 10.1097/00004872-200018060-00002.

Cooney RV, Custer LJ, Okinaka L, Franke AA: Effects of dietary sesame seeds on plasma tocopherol levels. Nutr Cancer. 2001, 39: 66-71. 10.1207/S15327914nc391_9.

Ikeda S, Kagaya M, Kobayashi K, Tohyama T, Kiso Y, Higuchi N, Yamashita K: Dietary sesame lignans decrease lipid peroxidation in rats fed docosahexaenoic acid. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2003, 49: 270-276.

Kang MH, Naito M, Tsujihara N, Osawa T: Sesamolin inhibits lipid peroxidation in rat liver and kidney. J Nutr. 1998, 128: 1018-1022.

Nakai M, Harada M, Nakahara K, Akimoto K, Shibata H, Miki W, Kiso Y: Novel antioxidative metabolites in rat liver with ingested sesamin. J Agric Food Chem. 2003, 51: 1666-1670. 10.1021/jf0258961.

Yamashita K, Iizuka Y, Imai T, Namiki M: Sesame seed and its lignans produce marked enhancement of vitamin E activity in rats fed a low alpha-tocopherol diet. Lipids. 1995, 30: 1019-1028. 10.1007/BF02536287.

Boshtam M, Rafiei M, Sadeghi K, Sarraf-Zadegan N: Vitamin E can reduce blood pressure in mild hypertensives. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2002, 72: 309-314. 10.1024/0300-9831.72.5.309.

Miyawaki T, Aono H, Toyoda-Ono Y, Maeda H, Kiso Y, Moriyama K: Antihypertensive effects of sesamin in humans. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2009, 55: 87-91. 10.3177/jnsv.55.87.

Sankar D, Rao MR, Sambandam G, Pugalendi KV: Effect of sesame oil on diuretics or β-blockers in the modulation of blood pressure, anthropometry, lipid profile, and redox status. Yale J Biol Med. 2006, 79: 19-26.

Sankar D, Sambandam G, Rao MR, Pugalendi KV: Modulation of blood pressure, lipid profiles and redox status in hypertensive patients taking different edible oils. Clin Chim Acta. 2005, 355: 97-104. 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.12.009.

Ward NC, Wu JH, Clarke MW, Puddey IB, Burke V, Croft KD, Hodgson JM: The effect of vitamin E on blood pressure in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2007, 25: 227-234. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000254373.96111.43.

Economides PA, Khaodhiar L, Caselli A, Caballero AE, Keenan H, Bursell SE, King GL, Johnstone MT, Horton RS, Veves A: The effect of vitamin E on endothelial function of micro- and macrocirculation and left ventricular function in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2005, 54: 204-211. 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.204.

Palumbo G, Avanzini F, Alli C, Roncaglioni MC, Ronchi E, Cristofari M, Capra A, Rossi S, Nosotti L, Costantini C, Cavalera C: Effects of vitamin E on clinic and ambulatory blood pressure in treated hypertensive patients. Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project (PPP) - Hypertension study. Am J Hypertens. 2000, 5 (Pt 1): 564-567.

Brigelius-Flohé R: Vitamin E and drug metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003, 305: 737-740. 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00811-8.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003, 289: 2560-2571. 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560.

Kontush A, Spranger T, Reich A, Baum K, Beisiegel U: Lipophilic antioxidants in blood plasma as markers of atherosclerosis: the role of alpha-carotene and gamma-tocopherol. Atherosclerosis. 1999, 144: 117-122.

Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board: Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. 2000, Washington, DC: National Academy Press

Rangkadilok N, Pholphana N, Mahidol C, Wongyai W, Saengsooksree K, Nookabkaew S, Satayavivad J: Variation of sesamin, sesamolin and tocopherols in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seeds and oil products in Thailand. Food Chemistry. 2010, 122: 724-730. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.044.

Draper HH, Squires EJ, Mahmoodi H, Wu J, Agarwal S, Hadley M: A comparative evaluation of thiobarbituric acid methods for the determination of malondialdehyde in biological materials. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993, 15: 353-363. 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90035-S.

Thurnham DI, Smith E, Flora PS: Concurrent liquid-chromatographic assay of retinol, alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, lycopene, and beta-cryptoxanthin in plasma, with tocopherol acetate as internal standard. Clin Chem. 1988, 34: 377-381.

Stamler J, Rose G, Stamler R, Elliott P, Dyer A, Marmot M: INTERSALT study finding: public health and medical care implications. Hypertension. 1989, 14: 570-577.

Noguchi T, Ikeda K, Sasaki Y, Yamamoto J, Yamori Y: Effects of vitamin E and sesamin on hypertension and cerebral thrombogenesis in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004, 31 (Suppl 2): 24-26.

Kamal-Eldin A, Frank J, Razdan A, Tengblad S, Basu S, Vessby B: Effects of dietary phenolic compounds on tocopherol, cholesterol, and fatty acids in rats. Lipids. 2000, 35: 427-435. 10.1007/s11745-000-541-y.

Ikeda S, Abe C, Uchida T, Ichikawa T, Horio F, Yamashita K: Dietary sesame seed and its lignan increase both ascorbic acid concentration in some tissues and urinary excretion by stimulating biosynthesis in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2007, 53: 383-392. 10.3177/jnsv.53.383.

Ito H, Torii M, Suzuki T: Comparative study on free radical injury in the endothelium of SHR and WKY aorta. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995, 22 (Suppl 2): 157-159.

Thomas SR, Chen K, Keaney JF: Oxidative stress and endothelial nitric oxide bioactivity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003, 5: 181-194. 10.1089/152308603764816541.

Ward NC, Hodgson JM, Puddey IB, Mori TA, Beilin LJ, Croft KD: Oxidative stress in human hypertension: association with antihypertensive treatment, gender, nutrition, and lifestyle. Free Radical Biol Med. 2004, 36: 226-232. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.10.021.

Li D, Saldeen T, Romeo F, Mehta JL: Relative effects of alpha- and gamma-tocopherol on low-density lipoprotein oxidation and superoxide dismutase and nitric oxide synthase activity and protein expression in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 1999, 4: 219-226. 10.1177/107424849900400403.

van Aalst JA, Burmeister W, Fox PL, Graham LM: Alpha-tocopherol preserves endothelial cell migration in the presence of cell-oxidized low-density lipoprotein by inhibiting changes in cell membrane fluidity. J Vasc Surg. 2004, 39: 229-237. 10.1016/S0741-5214(03)01038-3.

Pezeshk A, Derick Dalhouse A: Vitamin E, membrane fluidity, and blood pressure in hypertensive and normotensive rats. Life Sci. 2000, 67: 1881-1889. 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00775-X.

Lee CC, Chen PR, Lin S, Tsai SC, Wang BW, Chen WW, Tsai CE, Shyu KG: Sesamin induces nitric oxide and decreases endothelin-1 production in HUVECs: possible implications for its antihypertensive effect. J Hypertens. 2004, 22: 2329-2338. 10.1097/00004872-200412000-00015.

Wu JH, Hodgson JM, Clarke MW, Indrawan AP, Barden AE, Puddey IB, Croft KD: Inhibition of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthesis using specific plant lignans: in vitro and human studies. Hypertension. 2009, 54: 1151-1158. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139352.

Nakano D, Kwak CJ, Fujii K, Ikemura K, Satake A, Ohkita M, Takaoka M, Ono Y, Nakai M, Tomimori N, Kiso Y, Matsumura Y: Sesamin metabolites induce an endothelial nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation through their antioxidative property-independent mechanisms: possible involvement of the metabolites in the antihypertensive effect of sesamin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006, 318: 328-335. 10.1124/jpet.105.100149.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the assistance of the physical therapists at Queen Sirikit Heart Center of Northeast Thailand. We also appreciate Exercise and Sport Sciences Development and Research Group and Cardiovascular Research Group, Khon Kaen University (a grant number 511010008), Thailand for financial supports. We also would like to thank all subjects for their enthusiastic participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors are applying for a patent on black sesame meal.

Authors' contributions

JW participated in the design of the study and carried out the plasma MDA and vitamin E assay, physiological measurements and statistical analysis. NW prepared the black sesame meal. PB carried out the vitamin E assay. SS performed the medical cover. NL conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination. NR analyzed vitamin E and lignans in black sesame meal. JW and NL drafted the manuscript. NL is a member of Exercise and Sport Sciences Development and Research Group. NW, CS, NS, NK, SS and YT are members of Cardiovascular Research Group. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wichitsranoi, J., Weerapreeyakul, N., Boonsiri, P. et al. Antihypertensive and antioxidant effects of dietary black sesame meal in pre-hypertensive humans. Nutr J 10, 82 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-82

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-82