Abstract

Background

Following its recent re-emergence, malaria has gained renewed attention as a serious infectious disease in Korea. Three species of the Hyrcanusgroup, Anopheles lesteri, Anopheles sinensis and Anopheles pullus, have long been suspected malaria vectors. However, opinions about their vector ability are controversial. The present study was designed with the aim of determining the susceptibility of these mosquitoes to a Korean isolate of Plasmodium vivax. Also, An. sinensis is primarily suspected to be vector of malaria in Korea, but in Thailand, the same species is described to have less medical importance. Therefore, comparative susceptibility of Thai and Korean strains of An. sinensis with Thai strain of P. vivax may be helpful to understand whether these geographically different strains exhibit differences in their susceptibility or not.

Methods

The comparative susceptibility of An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus was studied by feeding laboratory-reared mosquitoes on blood from patients carrying gametocytes from Korea and Thailand.

Results

In experimental feeding with Korean strain of P. vivax, oocysts developed in An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus. Salivary gland sporozoites were detected only in An. lesteri and An. sinensis but not in An. pullus. Large differences were found in the number of sporozoites in the salivary glands, with An. lesteri carrying much higher densities, up to 2,105 sporozoites in a single microscope field of 750 × 560 μM, whereas a maximum of 14 sporozoites were found in any individual salivary gland of An. sinensis. Similar results were obtained from a susceptibility test of two different strains of An. sinensis to Thai isolate of P. vivax, and differences in vector susceptibility according to geographical variation were not detected.

Conclusion

The high sporozoite rate and sporozoite loads of An. lesteri indicate that this species is highly susceptible to infection with P. vivax. Anopheles sinensis appears to have a markedly reduced ability to develop salivary gland infection, whilst in An. pullus, no sporozoites were found in the salivary glands. Provided that the survival rate of An. lesteri is sufficiently high in the field, it would be a highly competent vector of vivax malaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Plasmodium vivax malaria has re-emerged in many malaria-endemic areas, where the disease was believed to have been eradicated [1]. In South Korea, it was assumed that malaria had been eradicated, since no indigenous case was reported after 1978. However, following the detection of a case in 1993, the annual incidence of malaria increased dramatically and reached a peak of 4,142 cases in 2000 [2–5]. In the meantime, malaria cases in North Korea increased from 1,085 in 1998 to 296,540 in 2001 [6]. As a result, malaria has gained renewed attention as a public health problem throughout the Korean Peninsula.

So far, eight anopheline mosquitoes have been reported from South Korea. Six of these species belong to the Hyrcanus group: Anopheles sinensis, Anopheles lesteri, Anopheles pullus, Anopheles sineroides, Anopheles kleini and Anopheles belenrae [7–10]. Two other non-Hyrcanus group species are Anopheles koreicus and Anopheles lindesayi japonicus [7].

Since vivax malaria has been recognized as an endemic disease particular to countries in the Far East Asia, including Korea, efforts to find the main vector(s) have continuously proceeded from Korea, Japan and China [7, 11–13]. However, there is currently no available report regarding the vector susceptibility of the two non-Hyrcanus species and An. sineroides, because these species are very rare in Korea, Japan and China and, are thus considered medically less important [7, 14, 15]. Although there is some published literature on the two newly reported species, An. belenrae and An. kleini [9], the biting behaviour, larval habitats, and medical importance of these species are still unknown [16]. The results of older studies on the vector abilities of An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus are controversial. Anopheles sinensis has long been considered a primary and strong vector in Korea and Japan [11, 12, 15, 17], while in countries like China and Thailand, this mosquito is treated as a refractory vector with weak transmission capability [13, 18, 19].

Although An. lesteri has been considered a minor and weak vector in Korea and Japan, studies in China showed that it was an important vector [20]. Conflicting reports on the vector ability of An. pullus may also be found [12, 4], with some suggesting that it is a malaria vector whereas others indicate otherwise [21]. Thus, the malarial susceptibility of these vectors remains to be clarified.

In this study, three species of the Hyrcanus group, An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus were experimentally infected with a Korean isolate of P. vivax and the malarial susceptibility of these species was analysed based on their ability to develop oocysts in the midgut and sporozoites in salivary glands. To substantiate the findings of the above experiments and to further understand and verify the existing differences in vector abilities of two geographically distant strains of An. sinensis from Korea and Thailand, experimental infections were conducted with a Thai isolate, and the ability of both these strains to develop oocysts and sporozoites was determined.

Methods

Colonization of mosquitoes

Three mosquito lines of the Korean Anopheles raised in the laboratory were An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus. Among these, An. sinensis and An. pullu s were collected from Paju City, Gyeonggi-do Province, while An. lesteri was collected from So-Rae District, Incheon City in South Korea. The Thai strain of An. sinensis was collected from Mae Tang District, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Anopheles cracens was in a free-mating colony established for more than two decades in the insectariums of the Department of Parasitology, Chiang Mai University, Thailand and was used as a control, since it is known to be highly susceptible to P. vivax [22]. These colonies were reared using the method described by Park et al [23] in an insectary room at 27 ± 2°C, 70–80% relative humidity with 12:12 hr light and dark photoperiods adjusted by fluorescent lighting.

Infected blood

Blood containing gametocytes of Korean P. vivax was supplied by the National Institute of Health (KNIH), from a patient seeking treatment at Gimpo, Gyeonggi-do province. The Thai strain of P. vivax was obtained from malaria patient infected in Mae Tang District of Chiang Mai Province. Informed consent was obtained from the patients before collection and the study protocols were approved by Internal Review Board of Korea National Institute of Health and Thailand Office for Vector Borne Diseases Control, Department of Communicable Diseases Control, Ministry of Public Health. Giemsa staining of the blood film was performed and gametocytes were counted. The gametocyte density of the Korean isolate of P. vivax was 36 gametocytes/200 White Blood Cells (WBC) while that of the Thai strain was 26 gametocytes/200 WBC.

Infection of mosquitoes with P. vivax gametocytes

Three to five days old females were used for infection. To enhance their willingness to feed, the mosquitoes were starved for 12 hours prior to infection and were transferred to paper cups of size 8.5 cm in diameter and 11 cm in depth (about 50 females per cup). The mosquitoes were fed on infected blood containing gametocytes through an artificial membrane feeding technique described by Chomcharn et al [24]. The mosquitoes were allowed to feed for one hour.

Unfed mosquitoes were removed and the fully engorged females were carefully handled and were kept in the insectary. Mosquitoes were then fed on cotton patches, which were soaked in 5% sucrose solution and changed every day, until the mosquitoes were dissected. During infection, three lines of the Korean mosquito: An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus were infected with Korean isolate of P. vivax, while strains of An. sinensis from Thailand and Korea together with An. cracens were infected with Thai isolate of P. vivax.

Eight and 14 days after feeding, mosquitoes were dissected to detect oocysts in the midgut and sporozoites in the salivary glands respectively. Counting of oocysts in mosquitoes was followed by examining wet mounts of the midgut stained in 0.1% mercurochrome and freely moving sporozoites were carefully detected from salivary glands placed in a drop of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2).

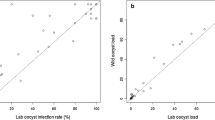

To explore differences in densities of the salivary gland sporozoites between An. lesteri and An. sinensis, two methods were used: 1) for An. lesteri, micrographs were taken at 100× magnification using a camera (Motic Cam 2000) mounted on a compound microscope (Leica DM 2500) and counting of sporozoites was performed within a captured micrograph, the corresponding area of which was approximately 750 μm × 560 μm; 2) sporozoites were counted from whole salivary glands from An. sinensis and were compared to the sporozoite loads within a single microscopic field of An. lesteri. The above counting and comparative procedures were developed because in highly infected An. lesteri, the direct counting of several hundreds of moving sporozoites while observing through the microscope was difficult. It was sometimes impossible to count all of them from salivary glands while in An. sinensis any such possibilities were less and few numbers of sporozoites were directly counted by changing fields. Depending on counting, mosquitoes were graded as 1+ (1–10 sporozoites), 2+ (11–100 sporozoites), 3+ (101–1,000 sporozoites) and 4+ (above 1,000 sporozoites) [25]. The total number of +'s recorded for all infected mosquitoes was gland indexes in terms of sporozoites load.

Results

Infection with Korean strain of Plasmodium vivax

As indicated by oocysts developed in the midgut, infections were detected in all three species eight days post feeding with Korean strain of P. vivax. However, An. lesteri was highly susceptible, in that all nine mosquitoes carried oocysts (100%). Compared to An. lesteri, fewer percent of An. sinesis (87%) and An. pullus (83%) developed oocysts.

During 14 days dissections, all 14 dissected An. lesteri contained oocysts. However, fewer An. sinensis and An. pullus do so. In addition, when detached salivary glands of the infected mosquitoes were examined, nine out of 14 An. lesteri (64%) and only two out of 19 An. sinensis (11%) contained sporozoites, while the examined salivary glands of all 6 An. pullus lacked sporozoites (Table 1).

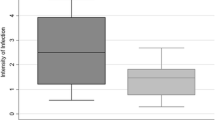

Even if few numbers of An. sinensis contained salivary gland sporozoites, compared to An. lesteri, the sporozoite loads in these species were very low (Figure 1). The highest number of salivary gland sporozoites recorded from An. sinensis was 14. Between two positive An. sinensis, one had a gland index of 1+ (< 10 sporozoites) and the other had 2+ (11–100 sporozoites). While the lowest and highest numbers of sporozoites counted in one microscopic field of An. lesteri were 78 and 2,105. Among 9 infected An. lesteri, one had gland index of 2+ (11–100 sporozoites), four were with 3+ (101–1,000 sporozoites) and remaining four were with 4+ (> 1,000 sporozoites), respectively. When compared to An. sinensis, the lowest and highest numbers of sporozoites of An. lesteri, even in a single microscopic field, were 5–150 times more intense.

Sporozoites detected from salivary gland of the infected mosquitoes. (A) High number of free flowing sporozoites released from the salivary gland of An. lesteri. (B) Arrow pointing to one among a few number of sporozoites released from squashed salivary gland of An. sinensis. Dissection was done 14 days post infection. Bars = 15 μm.

Infection with Thai strain of Plasmodium vivax

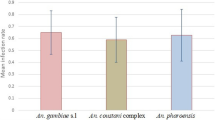

When mosquitoes were dissected eight days after feeding with Thai strain of P. vivax, equal percent of An. sinensis from Thailand and Korea (88%) develop oocysts, except differences were seen in number of the midgut oocysts they carried. All seven dissected specimens of An. cracens (100%), the control species, produced higher number of oocysts compared to both strains of An. sinensis.

Despite 14 days of oocyst development, sporozoites were not detected from the Thai strains of An. sinensis while only one out of 20 specimens of Korean strain (5%) contained salivary gland sporozoites. Furthermore, salivary gland sporozoites were detected from of all An. cracens (100%), the control species (Table 2).

Discussion

The abundance of An. sinensis in the Orient led to early suspicions of its role as a vector, but questions as to its role have continued for several decades [13, 15, 18]. The first successful study on experimental malarial transmission in An. sinensis was conducted by Tsuzuki in Japan, in 1902, which Kamimura suggested later on was actually An. lesteri [7]. Subsequently, Otsuru and Ohmori [15] stated that An. sinensis had a similar ability to develop malaria as An. lesteri in Japan.

Ho et al [13] showed that An. lesteri, besides being the primary vector of filarial parasites, was also the primary vector of malarial parasites in the hilly regions of the Yangtze valley (South China) and also pointed out that An. sinensis, due to its zoophilic behaviour, is an inefficient vector responsible for maintaining a low malaria endemicity in the broad flat rice plains of south China. Similarly, Harrison [26] opined that An. lesteri might well be a more efficient vector than An. sinensis. Lately, Liu [20] recorded a high number of infections in Anopheles anthropophagus (synonymized as An. lesteri) [27] from experimental feeding with P. falciparum gametocytes and also reported the natural infection rates of An. lesteri to be higher than An. sinensis in China. With such findings and along with other essential parameters (human-biting rate, human blood index, vectorial capacity and entomological inoculation rate), An. lesteri was considered to be 20 times more efficient as a malaria vector than An. sinensis in malaria infected regions in China [20, 28]. In South Korea however, the first natural infections in An. sinensis were reported in 1962 [11]. In a similar manner, Hong [12] also reported a very low number of sporozoite positive An. sinensis followed by An. pullus (previously called Anopheles yatshushiroensis). These early studies supported the primary and secondary vector status of An. sinensis and An. pullus.

In recent years, much of the understanding of vector susceptibilities of Korean Anopheles was based on Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Most of these studies indicated An. sinensis to be a vector [21, 29, 30], while recently, Lee et al [4] reported An. kleini and An. pullus to be stronger vectors than An. sinensis. Because Circumsporozoite Protein (CSP) detected by ELISA can equally be detected from developing oocysts, and sporozoites present in haemocoel, positive results from the test do not always indicate that the salivary glands are infected with sporozoites [31]. Thus, immunological evidence supporting the presence of CSP may indicate that the mosquito is a potential vector of malaria, but it is not proof that the sporozoites are located in the salivary glands and can be transmitted to a vertebrate host by a mosquito bite.

In this study, three Korean species of Hyrcanus group (An. lesteri, An. sinensis and An. pullus) were experimentally infected with an indigenous Korean isolate of P. vivax. After eight and 14 days post-infection, examination of midguts showed the presence of high number of oocysts in all three species. However, there were differences in their innate ability to develop sporozoites in the salivary glands. Sporozoites in salivary glands were detected from An. lesteri and An. sinensis but not from An. pullus. Though, sporozoites were detected from An. sinensis, they were very few as compared to An. lesteri. The maximum number of sporozoites in a salivary gland of An. sinensis was 14, which corresponded to the findings of Rongsriyam et al [19]. Assuming that two salivary glands have an equal number of sporozoites, fewer than 30 sporozoites are likely to develop in a pair of salivary glands of the above-mentioned mosquito. Earlier Ito et al [32] reported that mean densities of the sporozoites below 400 were not sufficient enough to initiate infections in mice. In such contest, low numbers of sporozoites detected from An. sinensis can be assumed to play less important role in initiating infections when compared to An. lesteri.

Because sporogony in P. vivax at 25°C is completed within 9 days [33], fourteen days time in this study, after which salivary glands were examined, should have been sufficient for sporozoites to reach to salivary glands. But compared to An. lesteri, very few number of An. sinensis contained salivary gland sporozoites however no sporozoites were detected in An. pullus. This suggests that developmental transitions couldn't proceed from oocysts to sporozoites formation in An. sinensis and An. pullus. Beier et al [33] described that inhibition in transitions from oocysts to sporozoites might be caused due to different mechanisms like oocysts failing to produce sporozoites, sporozoites failing to navigate successfully to the salivary glands, invading salivary glands or surviving in the salivary glands.

In addition to demonstrating sporozoites in salivary glands following laboratory infection, it is necessary to consider the natural survival rates of malaria vectors. At present, there are no connected reports with the matter in An. lesteri. Therefore, future studies regarding survival rate of An. lesteri in wild population can be more supporting evidence for this study. In Korea, the present study is the first of its kind, comparing the malarial susceptibilities of these members through successful malaria development within lab-raised clean colonies. The results are well congruent with Chinese and Thailand reports. So, the outcomes of this study have significant bearings within entire temperate regions where these species are abundant.

Conclusion

Under laboratory conditions, salivary gland sporozoites were developed in An. lesteri, as readily as in the well-recognized vector. Big differences were seen in the rate and densities of sporozoites between An. lesteri and An. sinensis, whereas sporozoites were not detected from salivary glands of An. pullus even after 14 days of oocysts development. Also, geographically distant strains of An. sinensis from Korea and Thailand were similar in their ability to support malaria development. Therefore, An. lesteri is highly susceptible to P. vivax malaria as compared to An. sinensis and An. pullus.

Thus, An. lesteri is a potential malaria vector and its presence may be described as an under-rated public health threat. However, comparative susceptibility of the remaining members of the Hyrcanus group will be important in future to understand their role in malaria epidemiology in Korea.

References

Sattabongkot J, Tsuboi T, Zollner GE, Sirichaisinthop J, Cui L: Plasmodium vivax transmission: chances for control?. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 20: 192-198. 10.1016/j.pt.2004.02.001.

Feighner BH, Pak SI, Novakoski WL, Kelsey LL, Strickman D: Reemergence of Plasmodium vivax malaria in the republic of Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998, 4: 295-297.

Chai IH, Lim GI, Yoon SN, Oh WI, Kim SJ, Chai JY: Occurrence of tertian malaria in a male patient who has never been abroad. Korean J Parasitol. 1994, 32: 195-200.

Lee WJ, Klein TA, Kim HC, Choi YM, Yoon SH, Chang KS, Chong ST, Lee IY, Jones JW, Jacobs JS, Sattabongkot J, Park JS: Anopheles kleini, Anopheles pullus, and Anopheles sinensis: potential vectors of Plasmodium vivax in the Republic of Korea. J Med Entomol. 2007, 44: 1086-1090. 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[1086:AKAPAA]2.0.CO;2.

WHO/UNICEF/RBM: World malaria Report 2005. [http://www.rbm.who.int/wmr2005/profiles/republicofkorea.pdf]

WHO/UNICEF/RBM: World malaria Report 2005. [http://www.rbm.who.int/wmr2005/profiles/dprkorea.pdf]

Tanaka K, Mizusawa K, Saugstad ES: A Revision of the Adult and Larval Mosquitoes of Japan (including the Ryukyu Archipelago and the Ogasawara Islands) and Korea (Diptera: Culicidae). 1979, Contribution of American Entomological Institute

Li C, Lee JS, Groebner JL, Kim HC, Klein TA, O'guinn ML, Wilkerson RC: A newly recognized species in the Anopheles Hyrcanus Group and molecular identification of related species from the republic of South Korea (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa. 2005, 939: 1-8.

Rueda LM: Two new species of Anopheles (Anopheles) Hyrcanus Group (Diptera: Culicidae) from the Republic of Korea. Zootaxa. 2005, 941: 1-26.

Hwang UW: Revisited ITS2 phylogeny of Anopheles (Anopheles) Hyrcanus group mosquitoes: reexamination of unidentified and misidentified ITS2 sequences. Parasitol Res. 2007, 101: 885-894. 10.1007/s00436-007-0553-4.

Ree HI, Hong HK, Paik YH: [Study on natural infection of Plasmodium vivax in Anopheles sinensis in Korea]. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1967, 5 (1): 3-4.

Hong JK: Ecological studies of important mosquitoes in Korea. PhD thesis. 1977, Dongkook University

Ho C, Chou TC, CH'EN TH, Hsueh AT: The Anopheles Hyrcanus Group and its relation to malaria in east China. Chin Med J. 1962, 81: 71-78.

Kim HC, Wilkerson RC, Pecor JE, Lee WJ, Lee JS, O'Guinn M, Klein TA: New Records and Reference Collection of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) on Jeju Island, Republic of Korea. Entomol Research. 2005, 35: 55-66. 10.1111/j.1748-5967.2005.tb00137.x.

Otsuru M, Ohmori Y: Malaria studies in Japan after World War II. Part II. The research for Anopheles sinensis sibling species group. Jpn J Exp Med. 1960, 30: 33-65.

Rueda LM, Kim HC, Klein TA, Pecor JE, Li C, Sithiprasasna R, Debboun M, Wilkerson RC: Distribution and larval habitat characteristics of Anopheles Hyrcanus Group and related mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) in South Korea. J Vector Ecol. 2006, 31: 198-205. 10.3376/1081-1710(2006)31[198:DALHCO]2.0.CO;2.

Ree HI: Studies on Anopheles sinensis, the vector species of vivax malaria in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2005, 43: 75-92. 10.3347/kjp.2005.43.3.75.

Harrison BA, Scanlon JE: Medical entomology studies-II. The Subgenus Anopheles in Thailand (Diptera: Culicidae). 1975, Contribution of American Entomological Institute

Rongsriyam Y, Jitpakdi A, Choochote W, Somboon P, Tookyang B, Suwonkerd W: Comparative susceptibility of two forms of Anopheles sinensis Wiedemann 1828 (Diptera: Culicidae) to infection with Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. yoelii and the determination of misleading factor for sporozoite identification. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998, 29: 159-167.

Liu C: Comparative studies on the role of Anopheles anthropophagus and Anopheles sinensis in malaria transmission in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1990, 11: 360-363.

Lee HW, Shin EH, Cho SH, Lee HI, Kim CL, Lee WG, Moon SU, Lee JS, Lee WJ, Kim TS: Detection of vivax malaria sporozoites naturally infected in Anopheline mosquitoes from endemic areas of northern parts of Gyeonggi-do (Province) in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2002, 40: 75-81.

Junkum A, Jitpakdi A, Jariyapan N, Komalamisra N, Somboon P, Suwonkerd W, Saejeng A, Bates PA, Choochote W: Susceptibility of two karyotypic forms of Anopheles aconitus (Diptera: Culicidae) to Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005, 47: 333-338.

Park SJ, Choochote W, Jitpakdi A, Junkum A, Kim SJ, Jariyapan N, Park JW, Min GS: Evidence for a conspecific relationship between two morphologically and cytologically different forms of Korean Anopheles pullus mosquito. Mol Cells. 2003, 16: 354-360.

Chomcharn Y, Surathin K, Bunnag D, Sucharit S, Harinasuta T: Effect of a single dose of primaquine on a Thai strain of Plasmodium falciparum. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1980, 11: 408-412.

Collins WE: Infection of mosquitoes with primate malaria. The molecular biology of the insect disease vectors, a method manual. Edited by: Crampton JR. 1997, New York: Chapman and Hall, 92-100. 1

Harrison BA: A Lectotype designation and description for Anopheles (An.) sinensis Wiedemann with a discussion of classification and vector status of this and some other Oriental Anopheles. Mosquito systematic. 1828, 5: 1-13.

Wilkerson RC, Li C, Rueda LM, Kim HC, Klein TA, Song GH, Strickman D: Molecular confirmation of Anopheles (Anopheles) lesteri from the Republic of South Korea and its genetic identity with An. (Ano.) anthropophagus from China (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa. 2003, 378: 1-14.

Xu BL, Su YP, Shang LY, Zhang HW: Malaria control in Henan Province, People's Republic of China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 74: 564-567.

Lee HW, Cho SH, Shin EH, Lee JS, Chai JY, Lee SH, Kim TS: Experimental infection of Anopheles sinensis with Korean isolates of Plasmodium vivax. Korean J Parasitol. 2001, 39: 177-183.

Coleman RE, Kiattibut C, Sattabongkot J, Ryan J, Burkett DA, Kim HC, Lee WJ, Klein TA: Evaluation of anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from the republic of Korea for Plasmodium vivax circumsporozoite protein. J Med Entomol. 2002, 39: 244-247.

Methods in Anopheles Research. [http://www.mr4.org/Portals/3/Methods_in_Anopheles_Research.pdf]

Ito J, Ghosh A, Moreira LA, Wimmer EA, Jacobs-Lorena M: Transgenic anopheline mosquitoes impaired in transmission of a malaria parasite. Nature. 2002, 417: 452-455. 10.1038/417452a.

Beier JC: Malaria parasite development in mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1998, 43: 519-543. 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.519.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to staffs at Public Health Centers of Ganghwa, Paju and Gimpo in South Korea for their direct/indirect efforts on collecting infected blood provided to National Institute of Health (KNIH). Authors also acknowledge our lab members at Department of Biological Sciences, Inha University and Department of Parasitology, Chiang Mai University for numerous helps regarding mosquito collection and rearing. This study was partially supported by grants of the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare (03-PJ1-PG1-CH01-0001) and Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (F01-2006-000-10274-0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MGS designed the present study. Prior to this experimental work, WC facilitated DJ and MHP for training on malaria susceptibilities and improved lab colonization of Anopheles mosquitoes. DJ and MHP conducted all experimental studies under the supervision of MGS and WC. Malaria-infected blood was obtained from WC, WS, TSK and JYK. DJ drafted the manuscript with MHP. All the authors read the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Joshi, D., Choochote, W., Park, MH. et al. The susceptibility of Anopheles lesteri to infection with Korean strain of Plasmodium vivax. Malar J 8, 42 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-8-42

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-8-42