Abstract

Background

The incidence of transfusion-transmitted malaria is very low in non-endemic countries due to strict donor selection. The optimal strategy to mitigate the risk of transfusion-transmitted malaria in non-endemic countries without unnecessary exclusion of blood donations is, however, still debated and asymptomatic carriers of Plasmodium species may still be qualified to donate blood for transfusion purposes.

Case description

In April 2011, a 59-year-old Dutch woman with spiking fevers for four days was diagnosed with a Plasmodium malariae infection. The patient had never been abroad, but nine weeks before, she had received red blood cell transfusion for anaemia. The presumptive diagnosis of transfusion-transmitted quartan malaria was made and subsequently confirmed by retrospective PCR analysis of donor blood samples. The donor was a 36-year-old Dutch male who started donating blood in May 2006. His travel history outside Europe included a trip to Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar in 2005, to Thailand in 2006 and to Costa Rica in 2007. He only used malaria prophylaxis during his travel to Africa. The donor did not show any abnormalities upon physical examination in 2011, while laboratory examination demonstrated a thrombocytopenia of 126 × 109/L as the sole abnormal finding since 2007. Thick blood smear analysis and the Plasmodium PCR confirmed an ongoing subclinical P. malariae infection. Chloroquine therapy was started, after which the infection cleared and thrombocyte count normalized. Fourteen other recipients who received red blood cells from the involved donor were traced. None of them developed malaria symptoms.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that P. malariae infections in non-immune travellers may occur without symptoms and persist subclinically for years. In addition, this case shows that these infections pose a threat to transfusion safety when subclinically infected persons donate blood after their return in a non-endemic malaria region.

Since thrombocytopenia was the only abnormality associated with the subclinical malaria infection in the donor, this case illustrates that an unexplained low platelet count after a visit to malaria-endemic countries may be an indicator for asymptomatic malaria even when caused by non-falciparum Plasmodium species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Transfusion-transmitted malaria (TTM) was first described in 1911 [1]. The most recent publication on global incidence of TTM, based on data from 1911 to 1979 [2], suggests that the incidence of TTM is about 145 reported cases per year, mostly confined to endemic countries. The relatively high likelihood of TTM via donor blood in sub-Saharan African countries is illustrated by a median prevalence of malaria, determined by microscopic evaluation of thick blood smears, of 10.2% (range: 0.7% in Kenya to 55% in Nigeria) in donor blood samples [3]. In endemic countries differentiating cases of TTM from natural infections is a challenge as malaria, occurring post-transfusion, can be the result of either a natural infection or transfusion-transmitted. Hence, the number of TTM in endemic countries is unquestionably under-reported. In striking contrast, in non-endemic countries the incidence of TTM is low, due to strict donor selection. Three cases were reported in Canada between 1994 and 1999 [4], 14 in the USA between 1990 and 1999 [5] and two in the UK since 1996 [6]. In the past decade, two cases were reported from other European countries, both with fatal consequences for the recipient [7, 8].

The optimal strategy to minimize the risk of TTM in non-endemic countries without unnecessary exclusion of blood donations is still a matter of debate. Reesink and colleagues provided an excellent overview of current strategies in a number of (mainly European) non-endemic countries [9, 10]. In short, most countries apply a strict donor deferral system based on travel history. However, this strategy is not optimal because many healthy donors are deferred unnecessarily, leading to donation loss, and lengthy deferrals may discourage donors to return at all [1]. Despite these strict donor deferral systems, some asymptomatic carriers of Plasmodium spp. may still be accepted for blood donation, and therefore the possibility of TTM is not completely excluded ([11, 12] and this case report).

Potential donor exposure to acquisition of malaria parasites is an increasing problem due to the substantial rise in global travelling and immigration. Therefore, it is more challenging than ever to ensure that the blood supply in non-endemic areas is devoid of potential malaria infections. Donor selection measures, such as geographical-risk questions in order to identify the donors at risk and to temporarily defer them, have been implemented by the blood bank community. In addition, some blood transfusion services in non-endemic areas implemented laboratory testing for shortened deferrals and/or to further reduce the risk of TTM. Donors can be tested by thick blood smear examination, malarial antibody testing and Plasmodium DNA detection by PCR [1, 13, 14]. It is widely accepted that none of these strategies is perfect, due to either lack of test sensitivity or unfavorable cost efficiency. The optimal approach for a given location will vary according to the background level of malaria risk faced by the donor and recipient population, in combination with the resources available.

Case presentation

A case is presented of transfusion-transmitted Plasmodium malariae infection from a long-term asymptomatic, non-immune traveller who had not experienced any clinical malaria before.

The recipient

A 59-year-old Dutch woman was seen at the outpatient clinic of the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) on April 14th 2011, because of spiking fevers for four days. Two months before, on February 14th, she underwent coronary-artery bypass surgery because of symptomatic coronary artery disease (Table 1). She had been feeling tired and nauseous and suffered from a non-productive cough and chest pain on deep inspiration since. She presented with daily fevers up to 38.8°C accompanied by chills, headache, nausea, and night sweats. Upon physical examination no abnormalities were found. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytopaenia (3.6 × 109/L) and thrombocytopenia (71 × 109/L). In the peripheral blood smear malaria parasites were seen which were subsequently identified as P. malariae by morphology and PCR. The parasitaemia was 2%. The patient was treated with chloroquine (25 mg/kg) and recovered completely.

The patient had never been abroad, neither had she recently been near an international airport. During her admission in February 2011, she had received one unit of packed red blood cells immediately after surgery. Hence, the presumptive diagnosis of transfusion-transmitted quartan malaria was made.

The donor

The Dutch blood bank was notified immediately about the presumptive diagnosis of TTM, after which the involved donor was informed and donation records were retrieved. Stored plasma from the involved donation as well as subsequent collected blood was examined for malaria (Tables 1 and 2). Thin and thick blood smears were negative, but immune fluorescence assay (IFA) was weakly positive and the sensitive Plasmodium- specific semi-quantitative real-time PCR showed a weak, though positive signal for P. malariae (Ct-value 38), confirming the persistent, asymptomatic P. malariae infection in the donor (Table 2).

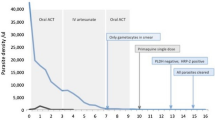

The blood donor was then referred to the Rotterdam Harbour Hospital in August 2011. The donor was a 36-year-old Dutch male without relevant medical history. In particular, he did not have any complaints of fever or chills in the past five years, nor did he take any medication. The donor had a secretarial job and lived about 50 km from the nearest international airport. He started donating blood in May 2006 and had given 15 whole blood donations until 2011 (Table 1). His travel history outside Europe included a trip to Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar in 2005, for which he had used atovaquone/proguanil as malaria prophylaxis. In 2006 and 2007 he visited Thailand and Costa Rica, respectively. On both occasions he did not use malaria chemoprophylaxis. According to the donor, he only stayed in low risk areas for malaria in Thailand. Therefore, the donor was only deferred from blood donations for six months following his visit to Africa and Costa Rica, according to the European Union directive (Figure 1) [15].

Time line of important donor events. Blood donations by the donor are indicated by open triangles. Visits to Africa, Thailand and Costa Rica are indicated by #, * and +, respectively. Deferral periods are indicated by grey bars. The solid line connects the platelet count numbers in course of time. The dashed line indicates the lower reference value for normal thrombocyte concentrations. The arrow indicates the start of oral chloroquine treatment.

Physical examination showed no abnormalities and the spleen was not enlarged (11.5 cm) on abdominal ultrasound examination. Laboratory examination demonstrated a thrombocytopenia of 126 × 109/L, hemoglobin 9.6 mmol/L, leucocyte count of 4.1 × 109/L and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 163 U/L. Standard malaria diagnostics by a malaria rapid test, thin and thick blood smears as well as quantitative buffy coat (QBC) analysis were negative. However, upon his second visit in November 2011, a single malaria parasite was detected after meticulous investigations of over five thick and five thin blood smears (Figure 2). A subsequently ordered Plasmodium- specific semi-quantitative real-time PCR was positive for P. malariae (Ct-value 37), confirming an ongoing subclinical P. malariae infection. The high Ct-values (37-38) observed in the subsequent blood specimens of the donor are close to the detection level of these tests and correspond to extremely low parasite numbers in the order of 1-100 parasites per mL.

Plasma and thrombocytes from the donor were never used for transfusion, but red blood cells were transfused into 15 recipients. None of the other 14 recipients developed malaria symptoms after transfusion. When the look-back procedure was performed, already 11 recipients had died of reasons other than malaria. The remaining three recipients were invited for a thorough malaria screening. One recipient was tested negative for malaria by both serology and real-time PCR. The two other recipients had no clinical signs of malaria and declined the invitation.

In retrospect, laboratory screening by the blood bank upon application of the donor to volunteer for platelet donations by aphaeresis, already revealed an unexplained thrombocytopenia (94 × 109/L) in February and May 2007. The blood bank staff then advised the donor to consult his general practitioner. To exclude other causes of thrombocytopenia apart from malaria, bone marrow morphology was examined, which demonstrated no abnormalities. In addition, no platelet antibodies were detected and the donor had normal thrombopoietin levels (13 E/mL; n = 4-32). All results together with the longstanding thrombocytopenia and travel history demonstrated that the donor must have had a subclinical P. malariae infection for at least four years and that the infection was most probably acquired during his travel through Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar in 2005 or during his visit to Thailand in 2006. He was treated orally with chloroquine 600 mg followed by a dose of 300 mg after six, 24 and 48 hours, respectively. On follow-up, his platelet count quickly normalized (Figure 2) and all malaria tests (thick and thin blood smears, QBC, malaria rapid tests, PCR, and serology) turned negative (Table 2).

Discussion

This case of TTM is remarkable, not only for being the first TTM case in the Netherlands in 43 years [16], but also because the donor was a non-immune traveller from a non-endemic country who never suffered from malaria and was without any symptoms for at least four years after acquisition of the P. malariae infection. Parasite counts in P. malariae are usually low, due to the low number of merozoites produced per asexual cycle in the erythrocyte, the slow replication cycle of 72 hours in erythrocytes and the preference of the parasite to develop in older erythrocytes. These factors usually allow for earlier development of immunity by the human host if left untreated. Blood stage P. malariae can persist for extremely long periods, often, it is believed, for the life of the human host [17]. Although subclinical malaria is relatively common in endemic countries [18], asymptomatic P. malariae infections in non-immune travellers are probably very rare, as reports of experimental P. malariae infections for the treatment of neurosyphilis patients between 1940 and 1963 recorded only a single patient without fever out of 69 infected patients [17, 19].

Thrombocytopenia is a common feature of malaria, occurring in 24-93% of cases of acute disease [20, 21]. In asymptomatic Plasmodium spp. carriers thrombocyte numbers are unknown, although one paper from Nigeria showed that asymptomatic carriers of Plasmodium spp. had a moderately lower platelet count than non-parasitaemic subjects [22]. The only abnormality in the donor in this case was a thrombocytopenia that was first observed in May 2007 and persisted until the malaria infection was cleared by chloroquine treatment. This now suggests that thrombocytopenia may be an indicator for asymptomatic infections by Plasmodium species other than P. falciparum as well. Further studies are needed to determine whether, and to what extent, this finding holds true in a larger group of asymptomatic carriers of Plasmodium spp.

For asymptomatic visitors to malaria-endemic areas, other than ex-residents and individuals with a history of malaria infection, the European Union directive for technical requirements for blood and blood components states that they shall be excluded from blood donation for six months after leaving the endemic area [15]. The donor in this case was qualified to donate blood according with the provisions of this directive (Table 1). This illustrates that a donor deferral policy based on geographic-risks reduces the risks of TTM, but cannot prevent incidents from occurring. It is noteworthy that the most commonly used serological test for screening donors for IgG antibodies to Plasmodium spp., the Malaria Total Antibody EIA kit (Lab21, Healthcare Ltd., Kentford, UK), used by the Dutch blood bank as well as by several other blood transfusion services in non-endemic countries to shorten deferral periods for ex-residents of malaria endemic areas and for individuals with a history of malaria, did not detect this asymptomatic malaria infection in the donor. This test was performed retrospectively (Table 2).

Only expensive methods, such as the sensitive serological immune fluorescence assay (IFA) and real-time PCR analysis (Table 2), did detect the asymptomatic P. malariae infection in the donor. As long as effective methods for pathogen inactivation of red cell units or whole blood are not available, cases of TTM can continue to occur in areas that are not endemic for malaria, irrespective of the safety measures currently adopted by the blood bank community.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that asymptomatic chronic P. malariae infections can occur in non-immune persons after a visit to malaria-endemic areas and thus pose a continued threat to transfusion safety. Since thrombocytopenia was the only abnormality associated with this asymptomatic P. malariae infection in the donor, an unexplained low platelet count may be an indicator for asymptomatic malaria even when caused by non-falciparum Plasmodium species.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Kitchen AD, Chiodini PL: Malaria and blood transfusion. Vox Sang. 2006, 90: 77-84. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00733.x.

Bruce-Chwatt LJ: Transfusion malaria revisited. Trop Dis Bull. 1982, 79: 827-840.

Owusu-Ofori AK, Parry C, Bates I: Transfusion-transmitted malaria in countries where malaria is endemic: a review of the literature from sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 51: 1192-1198. 10.1086/656806.

Slinger R, Giulivi A, Bodie-Collins M, Hindieh F, John RS, Sher G, Goldman M, Ricketts M, Kain KC: Transfusion-transmitted malaria in Canada. CMAJ. 2001, 164: 377-379.

Mungai M, Tegtmeier G, Chamberland M, Parise M: Transfusion-transmitted malaria in the United States from 1963 through 1999. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 1973-1978. 10.1056/NEJM200106283442603.

Watkins NA, Dobra S, Bennett P, Cairns J, Turner ML: The management of blood safety in the presence of uncertain risk: a United kingdom perspective. Transfus Med Rev. 2012, 26: 238-251. 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.09.003.

Frey-Wettstein M, Maier A, Markwalder K, Munch U: A case of transfusion transmitted malaria in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001, 131: 320-

Bruneel F, Thellier M, Eloy O, Mazier D, Boulard G, Danis M, Bedos JP: Transfusion-transmitted malaria. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30: 1851-1852.

Reesink HW: European strategies against the parasite transfusion risk. Transfus Clin Biol. 2005, 12: 1-4. 10.1016/j.tracli.2004.12.001.

Reesink HW, Panzer S, Wendel S, Levi JE, Ullum H, Ekblom-Kullberg S, Seifried E, Schmidt M, Shinar E, Prati D, Berzuini A, Ghosh S, Flesland Ø, Jeansson S, Zhiburt E, Piron M, Sauleda S, Ekermo B, Eglin R, Kitchen A, Dodd RY, Leiby DA, Katz LM, Kleinman S: The use of malaria antibody tests in the prevention of transfusion-transmitted malaria. Vox Sang. 2010, 98: 468-478. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01301.x.

Kitchen AD, Barbara JA, Hewitt PE: Documented cases of post-transfusion malaria occurring in England: a review in relation to current and proposed donor-selection guidelines. Vox Sang. 2005, 89: 77-80. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00661.x.

Garraud O, Assal A, Pelletier B, Danic B, Kerleguer A, David B, Joussemet M, de Micco P: Overview of revised measures to prevent malaria transmission by blood transfusion in France. Vox Sang. 2008, 95: 226-231. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01090.x.

Shehata N, Kohli M, Detsky A: The cost-effectiveness of screening blood donors for malaria by PCR. Transfusion. 2004, 44: 217-228. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.00644.x.

Seed CR, Kee G, Wong T, Law M, Ismay S: Assessing the safety and efficacy of a test-based, targeted donor screening strategy to minimize transfusion transmitted malaria. Vox Sang. 2010, 98: e182-e192. 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01251.x.

2004/33/EC CD: Implementing Directive 2002/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards certain technical requirements for blood and blood components. Off J Eur Union. 2004, L91: 25-39.

Stichting TRIP: TRIP rapport 2011 hemovigilantie. 2012

Collins WE, Jeffery GM: Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007, 20: 579-592. 10.1128/CMR.00027-07.

Laishram DD, Sutton PL, Nanda N, Sharma VL, Sobti RC, Carlton JM, Joshi H: The complexities of malaria disease manifestations with a focus on asymptomatic malaria. Malar J. 2012, 11: 29-10.1186/1475-2875-11-29.

McKenzie FE, Jeffery GM, Collins WE: Plasmodium malariae blood-stage dynamics. J Parasitol. 2001, 87: 626-637.

Lacerda MV, Mourao MP, Coelho HC, Santos JB: Thrombocytopenia in malaria: who cares?. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011, 106: 52-63.

te Witt R, van Wolfswinkel ME, Petit PL, van Hellemond JJ, Koelewijn R, van Belkum A, van Genderen PJ: Neopterin and procalcitonin are suitable biomarkers for exclusion of severe Plasmodium falciparum disease at the initial clinical assessment of travellers with imported malaria. Malar J. 2010, 9: 255-10.1186/1475-2875-9-255.

Igbeneghu C, Odaibo AB, Olaleye DO: Impact of asymptomatic malaria on some hematological parameters in the Iwo community in Southwestern Nigeria. Med Princ Pract. 2011, 20: 459-463. 10.1159/000327673.

Acknowledgements

Rob Koelewijn (Laboratory for Parasitology, Harbour Hospital Rotterdam) is thanked for preparation of Figure 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EEB, JvH, PG, LVL, ES, LV and PJW contributed to acquisition of the clinical and laboratory data. EEB prepared the draft version of manuscript and all authors contributed to the concept and design of manuscript and approved its final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Brouwer, E.E., van Hellemond, J.J., van Genderen, P.J. et al. A case report of transfusion-transmitted Plasmodium malariae from an asymptomatic non-immune traveller. Malar J 12, 439 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-439

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-439