Abstract

Background

The main vector of malaria in Solomon Islands is Anopheles farauti, which has a mainly coastal distribution. In Northern Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, high densities of An. farauti are supported by large brackish streams, which in the dry season are dammed by localized sand migration. The factors controlling the high larval productivity of these breeding sites have not been identified. Accordingly the influence of environmental factors on the presence and density of An. farauti larvae was assessed in three large naturally dammed streams.

Methods

Larval sites were mapped and anopheline larvae were collected monthly for 12 months (July 2007 to June 2008) from three streams using standard dippers. Larval collections were made from 10 locations spaced at 50 m intervals along the edge of each stream starting from the coast. At each collection point, floating filamentous algae, aquatic emergent plants, sun exposure, and salinity were measured. These environmental parameters along with rainfall were correlated with larval presence and density.

Results

The presence and abundance of An. farauti larvae varied between streams and was influenced by the month of collection, and distance from the ocean (p < 0.001). Larvae were more frequently present and more abundant within 50 m of the ocean during the dry season when the streams were dammed. The presence and density of larvae were positively associated with aquatic emergent plants (presence: p = 0.049; density: p = 0.001). Although filamentous algae did not influence the presence of larvae, this factor did significantly influence the density of larvae (p < 0.001). Rainfall for the month prior to sampling was negatively associated with both larval presence and abundance (p < 0.001), as high rainfall flushed larvae from the streams. Salinity significantly influenced both the presence (p = 0.002) and density (p = 0.014) of larvae, with larvae being most present and abundant in brackish water at < 10‰ seawater.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that the presence and abundance An. farauti larvae are influenced by environmental factors within the large streams. Understanding these parameters will allow for targeted cost effective implementation of source reduction and larviciding to support the frontline malaria control measures i.e. indoor residual spraying (IRS) and distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the Solomon Islands, malaria is transmitted by members of the Anopheles punctulatus group, including Anopheles farauti, Anopheles punctulatus and Anopheles koliensis[1]. Of these, An. punctulatus and An. koliensis have become uncommon and with limited distributions due to the past malaria eradication and control campaigns using indoor residual spraying (IRS) and the distribution of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) [2–4]. However, An. farauti changed its feeding behaviour from late night to outdoor early evening allowing it to avoid the insecticide [5]. An. farauti has become the major vector [1, 6, 7] and the early outdoor feeding behavior of An. farauti reduces the efficacy of IRS and ITNs; therefore, additional complementary vector control tools which target other stages of the mosquito life-cycle are needed, one example being larviciding.

An. farauti breeds both in fresh water and brackish with water up to 70% seawater [8–10]. An. farauti has been found to breed in a variety of fresh water filled depressions either natural or man-made such as drains, vehicle tracks, foot prints, pig wallows and borrow pits [11]. These sites are small and suffer the vagaries of rainfall, continually drying out or being flushed out; the adult output from these types of sites is low [8, 12]. In the coastal areas of the Solomon Islands very high densities of An. farauti are maintained due to the presence of large, permanent, brackish water streams and swamps that form, during the dry season, behind sand bars which block the flow of water into the sea [8, 12–14]. As many as 32 permanent coastal streams and swamps have been identified in the northern part of Guadalcanal [15, 16]. Previous studies have recorded high adult biting densities and parasite rates in the villages co-located with these coastal streams and swamps [4, 17].

Recent empirical [18, 19] and theoretical [20] studies have demonstrated that in situations where the proportion of indoor exposure to mosquito bites is less than 50%, the level of protection provided by IRS and LLINs, although still valuable, is significantly reduced. In such situations, additional control measures, i.e. larval control, should be considered when developing integrated vector control programmes to complement the use of IRS and LLINs. To support potential larviciding operations, knowledge of the environmental, biotic and climatic factors that regulate the presence and abundance of An. farauti in these breeding sites will enable programme managers to make evidence-based decisions that will best achieve the desired malaria control outcomes. The present study was carried out to determine the association of environmental factors with larval presence and abundance from three large coastal brackish water streams in North Guadalcanal and to discuss the implications for malaria control.

Methods

Study site

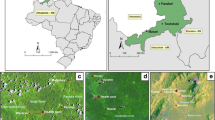

The study was conducted at three coastal streams at: Red Beach (9.255883° S, 160.062177° E), Gilutae (9.421717° S, 160.131569° E) and Komuporo (9.411026° S, 160.160111° E) (Figure 1) on the north coast of Guadalcanal Province from July 2007 to June 2008 (no collections were made in February of 2008 due to heavy rain and flooding). These large streams are approximately 5 km apart and measure 10-20 m in width with a length ranging from 500 m at Red Beach to up to 1,000 m at Gilutae and Komuporo. The criteria used in selecting the three sites for this study were a) a periodic sandbar blocking the outflow of water to the sea, producing a pool of stagnant water (Figure 2 A, B) and 2b) high levels of An. farauti breeding in the large streams. The communities adjacent to these brackish water streams are rural settlements scattered throughout the surrounding bushland on an extensive coastal plain (Figure 1), who experience intense year-round malaria transmission [4].

Larval collections

Monthly larval collections were made along the margin of the streams from the sea end to about 450 m inland. For each site, 10 sampling stations were set at 50 m apart, giving a total of 30 edge habitat sites (Figure 1). Each station was sampled using standard larval dippers (350 ml), 10 dips per site were taken from different locations with a 1 × 5 m sampling station along the edge of each stream. The collected larvae were counted, and 3rd and 4th instar larvae were reared through to adults which were identified by morphology using standard taxonomic keys [1]. A sample of these mosquitoes were desiccated on silica gel and transported to the National Yang-Ming University in Taiwan for molecular verification. The isomorphic species composition of the An. farauti complex was verified by polymerase chain reaction - restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) using the internal transcribed spacer region 2 of the ribosomal DNA. The analysis, DNA extraction, amplification, restriction digest, fragment separation, and visualization were as previously described [21].

Estimation of environmental factors

The percentage cover of filamentous algae and aquatic emergent plants was estimated using the method described by Mckenzie et al[22]. The percentage cover of filamentous algae, aquatic emergent plants was estimated using a 1 × 1 m quadrat within each 1 × 5 m sampling station. The quadrat, which was made from 4 × 1 m steel wires and floatable polystyrene foam, was placed systematically at four different places and spaced 25 cm apart along the length of the sampling station. Using a digital camera (Pentax, model K100D) photographs were taken from an angle as vertical as possible on the entire quadrat frame and corresponding quadrat label, taking care to avoid any shadows or patches of reflection off any water in the field of view. The total percentage cover of emergent plant vegetation was estimated by drawing the outline of any areas of algal cover onto tracing paper superimposed on the photographs and averaging the shaded area as a proportion of the total surface area using quadrat grids.

The percentage of sunlight was estimated using the method described by Nichols et al[23]. Here, at each larval sampling station, the larval sampling area that would be shaded by the riparian vegetation when the sun is directly overhead was estimated by drawing on a tracing paper as above and then superimposed the drawings on the percentage shading diagrams from Nichols et al, and the proportion shading was estimated [23]. Measurements were taken monthly at all larval sampling stations between 11:00 and 13:00 h.

Salinity was measured in situ with a Hand Held Refractometer (Atago Co.Ltd, Japan). One drop of surface water from each larval sampling station was placed on the prism face of the refractometer and the reading on the scale was taken. This procedure was repeated 3 times and the values were averaged.

Statistics

The association of the spatial factors (individual streams and the larval sampling stations), and the temporal factor (time of the collection - month) with anopheline larval presence was assessed with a generalized linear model (GLM) with a binomial distribution and a logit link function. The influence of six environmental factors on the presence and density of anopheline larvae was analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with large dammed streams, larval sampling stations and month as subject variables to account for repeated sampling. The six environmental factors were: filamentous algae, emergent aquatic plants, current rainfall, rainfall lagged by one month, salinity and sun exposure. The data was analyzed with two different distributions: 1) binary data (presence or absence) was fitted to a binomial distribution with a logit link function and 2) count data was fitted to a negative binomial distribution with a log link function because data was not normally distributed. For the density analysis, all larval collecting stations with zero counts of larvae were excluded. The level of significance for all tests was set at α = 0.05. All analyses were conducted with SPSS ver 17.

Results

A total of 2,930 An. farauti larvae were collected of which 83% (n = 1,932) were early instars (I-II) and 17% (n = 499) late instars (III-IV). Of the 459 specimens reared successfully to adults, all were identified morphologically as An. farauti s.l. and verified by PCR-RFLP as An. farauti. There was no An. punctulatus or An. koliensis found (Table 1).

Larval presence and abundance in relation to spatial and temporal factors

The spatial and temporal factors significantly influenced the presence or absence of An. farauti larvae: different times of the collections (χ2 = 59.08, df = 10, p < 0.001), between the three streams (χ2 = 22.32, df = 2, p < 0.001) and between the larval sampling stations (χ2 = 45.18, df = 9, p < 0.001). Regarding time of collection, larvae occurred more often, and at significantly higher densities, during the dry season (July 2007 to December 2007) compared to the wet season (January to June 2008) (Figure 3A, B). In the wet season, when the sandbars were naturally removed and the streams were open to the ocean, the larvae were more susceptible to being flushed away during heavy storms whereas during the dry season with the large streams closed off there is little water flow. In the selected large streams (sites), the mean number of anopheline larvae from Gilutae, 6.82 ± 2.11 per 10 dips/station (total: 750) was lower than at Red Beach, 9.42 ± 1.77 per 10 dips/station (total 1046) and Komporo, 9.45 ± 1.77 per 10 dips/station (total: 1134). The larval sampling stations, that were located within 50 meters from the sea had significantly more larvae than the upstream larval sampling stations (Figure 3 C, D).

Environmental factors in relation to spatial and temporal factors

Both spatial and temporal factors influenced the microclimate of the streams. Regarding temporal changes, the percentage algal cover was highest during the dry season compared to the wet season (Figure 4 A). Mean salinity ranged from 2‰ to 5‰ during the dry season, but was > 10‰ when the streams mouths were open during the wet season (Figure 4C). In contrast, there was no temporal difference in the percentage aquatic emergent plants (Figure 4D). Regarding spatial differences between the sampling stations, the percentage of algae and aquatic emergent plants and salinity was highest at stations less than 50 m from the sea (Figure 4 E, F, G).

Larval presence and environmental factors

The influence of the six environmental factors with larval presence or absence was assessed (Figure 5). Three factors significantly influenced larval presence (Table 2): emergent aquatic plants (p = 0.049), rainfall lagged by one month (p < 0.001) and salinity (p = 0.002). Emergent aquatic plants had a positive association with the presence of larvae, meaning that as the percentage of plants increased so did the chance of finding larvae. Rainfall, lagged by one month, had a negative association with larvae, when rainfall was high there was a lower chance of finding larvae the following month. With salinity, larvae were most commonly associated with brackish water being salinity readings ranged between 2‰ and 5‰ (Figure 5E). The factors that did not influence larval presence were: filamentous algae, sun exposure and current rainfall (Table 2, Figure 5).

Correlations between larval An. farauti presence and the 6 environmental factors in the study streams: filamentous algae, emergent aquatic plants, current rainfall, rainfall lagged by one month, salinity and sun exposure. The factors with a pink top-panel were significantly associated with An. farauti presence (see Table 2).

Larval density and environmental factors

The three factors that influenced the presence of larvae also significantly influenced the density of larvae (Table 2) with emergent aquatic plants being positively associated (p = 0.001), rainfall lagged by one month being negatively associated (p < 0.001) and salinity also negatively associated (p = 0.014) (Figure 6). Additionally larval density was significantly influenced by filamentous algae (p < 0.001). Filamentous algae had a positive association with the density of larvae, meaning that as algal coverage increased so did the density of larvae (Figure 6). The factors that did not influence larval density were: current rainfall and sun exposure (Table 2, Figure 6).

Correlations between larval An. farauti density and the 6 environmental factors in dammed brackish water streams: filamentous algae, emergent aquatic plants, current rainfall, rainfall lagged by one month, salinity and sun exposure. The factors with a pink top-panel were significantly associated with An. farauti density (see Table 2).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the presence and density of An. farauti larvae varied significantly between large streams, larval sampling stations, and the time of sampling. Within individual streams, larval densities were highest at stations near the ocean where the water was generally brackish (2-5‰ salinity) and the coverage of filamentous algae and emergent aquatic plants was highest. This corresponds with previous observations made in the same region of Guadalcanal (Vutu, 500 m east of Gilutae) where larval densities were highest at the stream mouth and decreased inland [24]. Larval presence and density varied seasonally and was primarily driven by rainfall and the opening of the stream mouth. When rainfall was high, the sandbar at the mouth of the streams were washed away and in the following month the presence and density of larvae was lower. Similarly, severe rainfall has previously been associated with reduced adult densities of An. farauti in Papua New Guinea [25] and also larval densities of Anopheles gambiae in Kenya [26].

An. farauti larval presence and abundance was negatively associated with salinity, with the most occurrences and densities of larvae occurring in brackish water (2 - 5‰ salinity), conversely high salinities (10 - 28‰ salinity) were associated with lower presence and densities of larvae. In the wild, An. farauti has been found breeding in water ranging from fresh to seawater (35‰), however the conditions influencing the selection of these sites was unknown as was the successful emergence of adults [27]. Laboratory studies have indicated that oviposition of An. farauti will occur in water ranging from fresh to 35‰ salinity [8, 28] however in choice studies there was a preference for fresh [28] or brackish water (< 50% seawater) [8]. Further laboratory studies have indicated that larval survival, from first instar, does not differ between fresh water and 50% seawater (96-92% survival) [9] and that survival from egg through to adults only occurs at < 65% seawater [8]. The work reported here is the first time that a detailed field study of larval salinity tolerance has been conducted longitudinally and while the salinity tolerance results generally concur with previous laboratory findings [9, 10] there was a preference with the An. farauti population for lower salinities of 2-5‰ [5-14% seawater], although this may be confounded by the high percentage of algae and emergent aquatic plants also found at the stream mouth.

Filamentous algae and aquatic emergent plants were important predictors for An. farauti presence and abundance. Some Anopheles species are known to exhibit thigmotaxis, a tendency to maintain bodily contact with solid objects [1] and are rarely found in open water. In the streams studied here, the algae and emergent aquatic plants were able to satisfy this requirement for An. farauti. The presence of vegetation also provides a food source and some protection from predators and currents [8]. Observations that An. farauti is associated with vegetation have been reported in Solomon Islands and Vanuatu [5, 8, 29]. Positive association with vegetations have also been reported for An. gambiae in Kenya [30, 31] and Anopheles pseudopunctipennis in Belize [32]. Filamentous algae have also been implicated in attracting gravid Anopheles females for oviposition [33].

Sun exposure was not an important predictor for An. farauti larval occurrence and abundance. This result contradicts previous findings that An. farauti prefer to breed in a more exposed environment compared to other anophelines of the Anopheles lungae complex [13]; however these observations were made prior to the use of molecular-based identification of An. farauti complex members and the observations may be confounded by the presence of Anopheles hinesorum or Anopheles irenicus, two other members of the An. farauti complex which occur in the Solomon Islands and which are morphologically very similar to An. farauti. In Vanuatu, where only An. farauti occurs, this species showed no preference for either shaded or sunlit sites, being commonly found in either [8]. The degree of exposure to sunlight is difficult to determine and interpret with regards to the occurrence of larvae. Breeding sites such as these dammed streams with surrounding vegetation and thick emergent vegetation will be shaded at some times of the day. As oviposition occurs at night, selection of either shaded or sunlit sites by gravid adults would not be possible and it would be the larvae themselves that select the degree of exposure to sunlight if such selection is important. It is more likely that a solid surface to rest against, avoidance of predators, and food requirements result in the larvae being in filamentous algae and aquatic emergent plants which always provide some shade.

This ecological data indicating where An. farauti larvae is most likely to be found and in what densities, is essential for designing cost-effective and evidence-based vector control programmes. Considering that these large streams are so highly productive, but relatively few in number, they present an opportunity where larval control could be targeted to the prime breeding habitats of An. farauti. The two most feasible options for targeting such highly productive large naturally dammed streams are: environmental manipulation or larviciding. Biological control using predacious fish would be ineffective as these streams are already stocked with local fish species which do not appear to have any impact on the larval populations most likely due to the protection offered by the vegetation.

With regards to environmental manipulation, managing the salinity and/or algae or plants in the system may be able to reduce the An. farauti larval population in such large dammed streams. It may be possible to manipulate the salinity and water flow of the streams by manually removing the sand bar. This would allow sea water into the site at high tides and also increase water flow removing vegetation from along the edges of the site and reducing suitable oviposition sites and larval harborage [15]. However, the mouth of the streams might be blocked again by sand migration in the dry season. For example, in Vanuatu An. farauti larvae and adults were eliminated from an entire village when one of these large dammed streams was naturally opened up to the sea, however when tides reestablished the sand dunes blocked the mouth and An. farauti quickly returned [8]. Alternatively, high density plastic pipelines could be installed underneath the sandbar to introduce the sea water into the dammed brackish water stream, but this technique is expensive and also requires constant maintenance. Other studies have manually manipulated the density of algae and plants in the environment to successfully reduce larval abundance; for example this has been seen in Mexico with the of immature stages of An. pseudopunctipennis[34, 35]. However such methods would be financially expensive, logistically difficult and maintenance is on-going.

The best practical control method would be using a slow release larvicide, for example insect growth regulators. Recent evidence from both Africa and Asia has demonstrated empirically [36–40] and theoretically [41, 42] that larviciding has potential to be an extremely successful vector control tool. For the current situation, granular formulations of a residual bio-larvicide could be placed along the edges of the brackish water streams (in some type of open weave bag). This study has established associations between environmental parameters and larval presence and abundance which would be useful in determining how extensive baiting would have to be to protect the people in the surrounding villages.

Conclusion

The present study described for the first time in Solomon Islands, the relationship between larvae occurrence and density with environmental factors. Obviously there are subtle microclimates preferred during larval development including, a positive association with filamentous algae and aquatic emergent plants, while salinities over 10% seawater showed a negative association with larval occurrence and density, as did rainfall and the wet season. Overall the findings in this study support the notion that larval control is a feasible option for vector control that could complement the wide-scale use of LLINs and IRS in the region. Tools such as larval control and source reduction present an excellent opportunity to build complementary integrated vector control programmes that will be able to hit the vector at different stages of the life cycle, something that will be essential for the Solomon Islands where the primary vector An. farauti tends to be exophagic and exophilic. There is a need for further research into the efficacy of various larval control options for use in North Guadalcanal; however our results indicate that environmental manipulation or larviciding are both feasible options.

References

Belkin JN: The mosquitoes of the South Pacific (Diptera, Culicidae). 1962, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

Slooff R: Mosquitoes collected in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate between March 1964 and October 1968 (Diptera: Culicidae). Entomologische Berichten. 1972, 32: 171-181.

Taylor B: Observations on malaria vectors of the Anopheles punctulatus complex in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. J Med Entomol. 1975, 11: 677-687.

Hii JLK, Kanai L, Foligela A, Kan SKP, Burkot TR, Wirtz RA: Impact of permethrin-impregnated mosquito nets compared with DDT house spraying against malaria transmission by Anopheles farauti and An. punctulatus in the Solomon Islands. Med Vet Entomol. 1993, 7: 333-338. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1993.tb00701.x.

Taylor B: Changes in the feeding behaviour of a malaria vector, Anopheles farauti Lav., following the use of DDT as a residual spray in houses in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. Tran R Entomol Soc Lond. 1975, 127: 227-292.

Beebe NW, Bakotee H, Ellis JT, Cooper RD: Differential ecology of Anopheles puntucaltus and three members of the Anopheles farauti complex of mosquitoes on Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, identified by PCR-RFLP analysis. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 41: 308-312.

Avery J: A review of the malaria eradication programme in the British Solomon Islands 1970-1972. PN GMed J. 1974, 17: 50-60.

Daggy RH: The biology and seasonal cycle of Anopheles farauti on Espirtu Santo, New Hebrides. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1945, 38: 3-13.

Sweeney AW: Larval salinity tolerances of the sibling species of Anopheles farauti. J Am Mosq Contrl Assoc. 1987, 8: 589-592.

Bell D, Bryan J, Cameron A, Foley D, Pholsyna K: Salinity tolerance of Anopheles farauti Laveran sensu stricto. P N G Med J. 1999, 42: 5-9.

Cooper RD, Waterson DGE, Frances SP, Beebe NW, Sweeney AW: Speciation and distribution of the members of the Anopheles punctulatus (Diptera: Culicidae) group in Papua New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 2002, 39: 16-27. 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.16.

Sweeney AW: Variations in density of Anopheles farauti Laveran in the Carteret Islands. PN G Med J. 1968, 11: 11-18.

Taylor B, Maffi M: A review of the mosquito fauna of the Solomon Islands (Diptera: Culicidae). Pacific Insects. 1978, 19: 165-248.

Charlwood JD, Graves PM, Alpers MP: The ecology of the Anopheles punctulatus group of mosqutioes from Papua New Guinea: A review of recent work. PNG Med J. 1986, 29: 19-26.

Paik Y-H: Influence of stagnation of water pathways on mosquito population density in connection with malaria transmission in the Solomon Islands. Jpn J Exp Med. 1987, 57: 47-52.

Government of Solomon Islands, WHO, I Wallis: Environmental modification for vector control. WHO. 1995, Report number WP/SOL/CTD/301

Hii JLK, Birley MH, Kanai L, Foligeli A, Wagner J: Comparative effects of permethrin-impregnated bednets and DDT house spraying on survival rates and oviposition interval of Anopheles farauti No. 1 (Diptera: Culicidae) in Solomon Islands. Ann Trop Med and Parasitol. 1995, 89: 521-529.

Bugoro H, Cooper RD, Butafa C, Iro'ofa C, Mackenzie DO, Chen CC, Russell TL: Bionomics of the malaria vector Anopheles farauti in Temotu province, Solomon Islands: issues for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2011, 10: 133-10.1186/1475-2875-10-133.

Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killen GF: Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011, 10: 80-10.1186/1475-2875-10-80.

Govella NJ, Okumu F, Killen GF: Isecticide-treated nets can reduce malaria transmission by mosquitoes which feed outdoors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 82: 415-419. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0579.

Beebe NW, Ellis JT, Cooper RD, Saul A: DNA sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA ITS2 region for the Anopheles punctulatus group of mosquitoes. Insect Mol Biol. 1999, 8: 381-390. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.83127.x.

Mckenzie LJ, Campbell S, Roder CA: Seagrass-Watch: Manual for mapping and monitoring seagrass resources by community (citizen) volunteers. 2001, (QFS, NFC, Cairns), 100-

Nichols S, Sloane P, Coysh J, Williams C, Norris R: Australia-wide assessment of river health: Australian Capital Territory AusRivAS sampling and processing mannual. 2002, Monitoring River Health Iniative Report # 14 Commonwealth of Australia and University of Canberra

Suzuki H: Malaria vector mosquitoes in the Solomon Islands. Malaria research in the Solomon Islands. Edited by: Ishii A, Nihei N, Sasa M. 1998, Tokyo: Inter Group Corporation, 104-113.

Charlwood JD, Birley MH, Dagoro H, Paru R, Holmes PR: Assessing Survival Rates of Anopheles farauti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Papua New Guinea. J Animal Ecol. 1985, 54: 1003-1016. 10.2307/4393.

Paaijmans KP, Wandago M, Githeko AK, Takken W: Unexpected high losses of Anopheles gambiae larvae due to rainfall. PLoS ONE. 2007, 11: e1146-

Cooper RD, Frances SP, Waterson DGE, Piper RG, Sweeney AW: Distribution of Anopheline mosquitoes in Northern Australia. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1996, 12: 656-663.

Foley DH, Bryan JH: Oviposition preference for freshwater in the coastal malaria vector, Anopheles farauti. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1999, 15: 291-294.

Laird M: Mosquitos and malaria in the hill country of the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands. Bull Entomol Res. 1955, 46: 275-289. 10.1017/S0007485300030911.

Mwangangi JM, Mbogo C, Muturi EJ, Nzovu JG, Kabiru EW, Githure JI, Novak RJ, Beier JC: Influence of biological and physiochemical characteristics of larval habitats on the body size of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) along the Kenyan coast. J Vector Borne Dis. 2007, 44: 122-127.

Fillinger U, Sombroek H, Majambere S, van Loon E, Takken W, Lindsay SW: Identifying the most productive breeding sites for malaria mosquitoes in the Gambia. Malar J. 2009, 8: 62-10.1186/1475-2875-8-62.

Bond JG, Arredondo-Jimerez JI, Rodriquez MH, Quiroz-martinez H, Williams T: Oviposition habitat selection for predator refuge and food source in a mosquito. Ecol Entomol. 2005, 30: 255-263. 10.1111/j.0307-6946.2005.00704.x.

Torres-Estrada JL, Meza-Alvarez RA, Cruz-Lopez L, Rodriguez MH, Arredondo-Jimenez JI: Attraction of gravid Anopheles pseudopunctipennis females to oviposition substrates by spyrogyra majuscula (Zygnematales: Zygnmataceae) algae under laboratory conditions. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2007, 23: 18-23. 10.2987/8756-971X(2007)23[18:AOGAPF]2.0.CO;2.

Bond JG, Quiroz-Martinez H, Rojas JC, Valle J, Ulloa A, Williams T: Impact of environmental manipulation for Anopheles pseudopunctipennis Theobaldcontrol on aquatic insect communities in southern Mexico. J Vect Ecol. 2007, 32: 41-53. 10.3376/1081-1710(2007)32[41:IOEMFA]2.0.CO;2.

Bond JG, Rojas JC, Arredondo-Jimenez JI, Quiroz-martinez H, Valle J, Williams T: Population control of the malaria vector Anopheles pseudopunctipennis by habitat manipulation. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2004, 271: 2161-2169. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2826.

Darabi H, Vatandoost H, Abaei MR, Gharibi O, Pakbaz F: Effectiveness of methoprene, an insect groth regulator against malaria vectors in Fars, Iran: A field study. Pakistan J Biol Sc. 2011, 14: 69-73.

Fillinger U, Lindsay SW: Suppression of exposure to malaria vectors by an order of magnitude using microbial larvicides in rural Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2006, 11: 1-4. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01544.x.

Geissbuhler Y, Kanady K, Chaki PP, Emidi B, Govella NJ, Mayagaya V, Matasiwa D, Mshinda H, Lindsay SW, Tanner M, Fillinger U, de castro MC, Killen GF: Microbial larvicide application by large-scale, community-based program reduces malaria infection prevalence in urban Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PloS ONE. 2009, 4: e5107-10.1371/journal.pone.0005107.

Majambere S, Lindsay SW, Green C, Kandeh B, Fillinger U: Microbial larvicides for malaria control in The Gambia. Malar J. 2007, 6: 76-10.1186/1475-2875-6-76.

Walker K, Lynch M: Contributions of Anopheles larval control to malaria suppression in tropical Africa: review of achievements and potential. Med Vet Entomol. 2007, 21: 2-21. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00674.x.

Killen GF, Fillinger U, Knols BG: Advantages of larval control for African malaria vectors: low mobility and behavioural responses of immature mosquito stages allow high effective coverage. Malar J. 2002, 1: 8-10.1186/1475-2875-1-8.

Yakob L, Yan G: Modelling the effects of integrating larval habitat source reduction and insecticide treated nets for malaria control. PloS ONE. 2009, 4: e6921-10.1371/journal.pone.0006921.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Vector-Borne Disease Control Programme in North Guadalcanal area, Alfred Siria, Dulcie Ausuta, Dr Kung-Yee Liang and I-Yu Tsao for technical assistance when carrying the entomological work in the field and in the laboratory. HB was supported by grant from the Taiwan International Development Fund and CCC was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Taiwan. This study was funded by Global Fund grant MWP-507-G05-M in 2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HB, JH conceived the study. HB, TLR, RDC analyzed the data. HB, RDC, TLR, CCC wrote the manuscript. HB, JH, CB, CI, AA, CCC performed the field collections. HB, CCC performed the molecular analysis. JH, RDC, BKKC, AB, TLR reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bugoro, H., Hii, J., Russell, T.L. et al. Influence of environmental factors on the abundance of Anopheles farauti larvae in large brackish water streams in Northern Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Malar J 10, 262 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-262

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-262