Abstract

A metagenomic library was prepared using pCC2FOS vector containing about 3.0 Gbp of community DNA from the microbial assemblage of activated sludge. Screening of a part of the un-amplified library resulted in the finding of 1 unique lipolytic clone capable of hydrolyzing tributyrin, in which an esterase gene was identified. This esterase/lipase gene consists of 834 bp and encodes a polypeptide (designated EstAS) of 277 amino acid residuals with a molecular mass of 31 kDa. Sequence analysis indicated that it showed 33% and 31% amino acid identity to esterase/lipase from Gemmata obscuriglobus UQM 2246 (ZP_02733109) and Yarrowia lipolytica CLIB122 (XP_504639), respectively; and several conserved regions were identified, including the putative active site, HSMGG, a catalytic triad (Ser92, His125 and Asp216) and a LHYFRG conserved motif. The EstAS was overexpressed, purified and shown to hydrolyse p-nitrophenyl (NP) esters of fatty acids with short chain lengths (≤ C8). This EstAS had optimal temperature and pH at 35°C and 9.0, respectively, by hydrolysis of p-NP hexanoate. It also exhibited the same level of stability over wide temperature and pH ranges and in the presence of metal ions or detergents. The high level of stability of esterase EstAS with its unique substrate specificities make itself highly useful for biotechnological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipolytic enzymes such as esterases (EC3.1.1.1) and lipases (EC3.1.1.3) catalyze both the fat hydrolysis and the synthesis of fatty acid esters including acylglycerides as biocatalysts [1]. Lipolytic enzymes are ubiquitous α/β hydrolyzing enzymes existed in animals, plants, and microbes, including fungi and bacteria. Microbial esterases are showing considerable industrial potential where their regiospecificity and enantioselectivity are desired characteristics [2], such as production of fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, in the food industry and are widely used in biotechnology [2–4].

Modern biotechnology has a steadily increasing demand for novel biocatalysts, thereby prompting the development of novel experimental approaches to find and identify novel biocatalyst-encoding genes. Metagenome is the total microbial genome directly isolated from natural environments, and the power of metagenomics is the access, without prior sequence information, to the so far uncultured majority, which is estimated to be more than 99% of the prokaryotic organisms [5–7]. In fact, the metagenomic approach was successful in searching for novel lipolytic enzymes in varied environments, and also, several genes encoding metagenomic esterases have been identified in metagenomic libraries prepared from varied environmental samples, including soils [6–9], marine sediment [10–12], pond and lake water [13–15], and tidal flat sediment [16].

Studies based on 16S rDNA library have extensively redefined and expanded our knowledge of microbial diversity in activated sludge from low-temperature aromatic wastewater treatment bioreactor, including members of various un-culturable groups (unpublished data). To the best of our knowledge, activated sludge microbial communities have not been exploited by culture-independent methods for isolation of lipolytic genes. Here, we report the isolation, sequence analysis, and enzymatic characterization of a novel esterase, EstAS, from an activated sludge derived metagenomic library. The discovery of EstAS led to the identification of a new family of bacterial lipolytic enzymes.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Activated sludge was collected from a low temperature sequencing batch bioreactor (SBR) treating nitrogen-containing aromatic wastewater in our laboratory.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

The starting strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics [17], at 12.5 μg/ml for chloramphenical, 100 μg/ml for ampicillin and 25 μg/ml for kanamycin.

DNA preparation and manipulation

E. coli cells were transformed by the calcium chloride procedure [17]. Recombinant plasmid DNA was isolated by the method of Birnboim and Doly [18] or with a Tian-prep Mini kit (TianGen). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatases were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, USA) or Takara (Tokyo, Japan) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Construction of metagenomic DNA library and sublibrary

Activated sludge DNA extraction was carried out using SDS and proteinase K treatment [19], and the removal of humic acids (HAs) prior to DNA extraction was conducted by using HAs removing buffer [20]. Approximately 100 μg of metagenomic DNA was run on a preparative pulsed-field gel (Bio-Rad CHEF DR®III; 0.1-40 s switch time, 6 V/cm, 0.5 × TBE buffer, 120° included angle, 16 h), and the appropriate size of DNA ranging from 30-50 kb was isolated, electroeluted, and dialyzed against 0.5 × TE buffer for further Fosmid library construction. The purified DNA fragments were end-repaired by End-repaired enzyme mix. After size fractionation and purification, the blunt-ended, 5'-phosphorylated DNA was ligated into the cloning-ready Copycontrol pCC2FOS vector, and the recombinant molecules were packaged in vitro with a MaxPlaxTM Lambda packaging kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The selected unique fosmid clone was named FosB12L1 (showing strong lipolytic activity on tributyrin plate), and purified, partially digested with Sau 3AI to obtain 3-5 kb size DNA, and ligated into a purified Bam HI/BAP pUC118 vector from Takara. Ligation products were transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells (Tiangen) and spread out on LB (ampicillin, 100 μg/ml) plates containing 1% (v/v) tributyrin as the indicator substrate [21].

Identification of lipolytic clones and DNA sequence analysis

The DNA fragment obtained was sequenced with primer walking method by SinoGenoMax Co. Ltd (Chinese National Human Genome Center, Beijing). The ORFs were analyzed using DNAstar (Lynnon Biosoft) and GeneTool software (Syngene), Database searches were performed with the BLAST program via GenomeNet World Wide Web server. Peptide sequences of various enzymes or subunits were extracted from National Center for Biotechnology Information (Washington, D.C).

Phylogenetic analysis

Deduced amino acid sequences of 8 lipolytic enzymes were subjected to protein phylogenetic analysis. Sequence alignment was performed by using CLUSTAL_W program [23] and visually examined with BoxShade Server program. Phylogenetic tree was generated using the neighbor joining method of Saitou and Nei [22] with MEGA 4.0 software [24].

Protein expression and purification

For the overexpression of EstAS, the full length of the estAS gene was amplified using primers EstAS-f and EstAS-r (Table 2) and high fidelity PrimeSTAR™HS DNA Polymerase (code: DR010SA, Takara). The primer pairs with restriction enzyme sites (underlined) for Hind III and Nde I were designed to generate an N-terminal His-tag of the recombinant esterase. The integrity of the nucleotide sequence of all newly constructed plasmids was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The EstAS gene was cloned into an expression vector, pET28a(+), and the recombinant plasmid pEstAS-His was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. When the cell density at 600 nm reached around 0.6, 1 mM isopropylthio-β-D-galactoside was added for the induction, following a further cultivation for 4 h at 30°C. Then cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM imidazole, and disrupted by sonication. The protein was applied to metal-chelating chromatography using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out according to Sambrook and Russell [17].

Characterization and biochemical properties of EstAS

The substrate specificity of the purified enzyme was analyzed using the following substrates of p-NP-fatty acyl esters [21, 25]: acetate (C2), butyrate (C4), hexanoate (C6), caprylate (C8), decanonate (C10), laurate (C12), myristate (C14) and palmitate (C16). The enzyme was incubated with the ester derivatives (0.5 mM) in 5 ml Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0) at 40°C for 10 min. The reaction was quenched by adding 5 ml trichloroacetic acid (0.5 mM) and then recovered the original pH value with 5.15 ml NaOH (0.5 mM), and the amount of released p-NP was determined by an absorption increase at 405 nm against an enzyme-free blank on a Biospec-1601 spectrophotometer [26, 27]. One unit of esterase is defined as the amount needed to release 1 μmol p-NP per min under the above conditions. The highest enzyme activity on a substrate (i. e. p-NP-hexanoate) was defined as 100%. To determine the presence of esterase activity, the triglyceride derivative 1,2-di-O-lauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid 6'-methylresorufin ester (DGGR) (Sigma Aldrich) was used as a chromogenic substrate, and the formation of methyresorufin was analyzed spectrophotometrically at 580 nm [1, 28, 29]. Candida rugosa lipase (Sigma Aldrich) was used as a positive control.

Using p-NP-hexanoate (0.5 mM) as substrate, the optimal temperature and pH of purified EstAS was determined, by measuring the enzyme activity after incubation at various temperatures (10-65°C) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) or after incubation at 35°C for 10 min in the following buffers: 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 5.0-7.5), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0-10.5).

Various metal ions (CoCl2, CaCl2, ZnCl2, MgCl2, K2SO4, FeSO4, CuSO4, Ni(NO3)2 and MnSO4), and chelating agent EDTA at final concentration of 1 mM were added to the enzyme in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), then assayed for esterase activity after preincubation at 35°C. Effect of detergents or reductors on esterase activity was determined by incubating the enzyme for 30 min at 35°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), containing (1%, v/v) Triton X-100, Tween 20 and 80, β-mercaptoethanol, 1, 4-dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and diethypyrocarbonate (DEPC), respectively. The enzyme activity without metal ions and detergents was defined as 100%.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The DNA sequence of EstAS was deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession number of FJ386490.

Results and discussion

Construction of a metagenomic library and screening

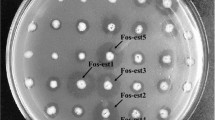

About 100 μg DNA was extracted from 1 g activated sludge (wet-weight), and 1.5 μg of size-selected, pulse-field gel-purified high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA suitable for fosmid cloning was obtained. 300 ng of 30-45 kb purified metagenomic DNA was ligated into the copy control pCC2FOS vector and transfected into E. coli EPI300-T1R, producing a metagenomic library of more than 100, 000 fosmids with insert sizes ranging from 28 kb to 40 kb (average size of 35 kb), covering approximately 3.0 Gbp of the total metagenomic DNA. The prokaryotic origin of the library was confirmed by end-sequencing of randomly selected fosmids and comparison with known ORFs in NCBI. Expression screening of the fosmid library based on the hydrolysis of emulsified tributyrin (1%) resulted in the detection of a recombinant clone, FosB12L1, forming a clear zone on the indicator plate.

Subcloning and identification of the esterase

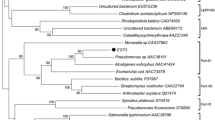

The DNA insert (36 kb) of fosmid B12L1 was partial digested by Sau 3AI and subcloned into pUC118, producing a subclone library of more than 3,000 clones with an average insert size of 3-5 kb. 300 subclones were screened for lipolytic activity. One subclone expressing extracellular lipase/esterase activity was sequenced and assembled into a contig of 3780 bp (data not shown). An ORF of 834 bp encoding a putative lipase/esterase (named EstAS) of 277 amino acid residuals was identified. Amino acid sequence alignment indicated that this EstAS showed quite low identity with other esterase/lipases, highest with the esterase/lipase from Gemmata obscuriglobus UQM 2246 (ZP_02733109, 33% identity), followed by the lipase from Yarrowia lipolytica CLIB122 (XP_504639, 31% identity), the putative lipase/esterase from Magnaporthe grisea 70-15 and Saccharomyces cerevisiase Tg12p (XP_368471, 31% identity; and NP_010343, 29% identity, respectively), members of the family of fungal hydrolases. And also, the EstAS contained a catalytic triad (Ser92, His125, and Asp249) and a LHYFRG conserved motif (starting from His36), as shown in Fig. 1, which is in close proximity to the active site contributing to the formation of the oxyanion hole that is likely to participate directly in the catalytic process [2, 30, 31]. Furthermore, to clarify the phylogenetic relationship of the EstAS with other esterases or lipases, a neighbour joining tree was constructed using the amino acid sequence, as shown in Fig. 2. In this tree, EstAS is located closest to the branch of esterase/lipase (accession number X53053) of strain Moraxella sp. TA144, and also Streptomyces sp. M11, Streptomyces albus G (accession numbers M86351 and U03114, respectively), which constitute family III lipases. This result might suggest that the EstAS is a new member of family III lipases.

Conserved sequence blocks from multiple sequence alignment of EstAS from activated sludge metagenomic library and other related proteins. Sequence alignment was carried out with CLUSTAL_W [24] and BoxShade Server http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html. XP_504639, esterase/lipase from Yarrowia lipolytica CLIB122; XP_368471, LipA from Magnaporthe grisea 70-15; NP_010343, esterase/lipase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tg12p; ZP_02733109, lipase from Gemmata obscuriglobus UQM 2246.

Phylogenetic analysis of EstAS and closely related proteins. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the program MEGA 4.0. Except for EstAS, the protein sequences for previously bacterial lipolytic enzymes were retrieved from GenBank http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. The numbers at node indicate the bootstrap percentages of 1000 resamples.

Expression and purification of recombinant EstAS

To investigate the property of this EstAS, EstAS gene was expressed as an N-terminal His-tag fusion protein using pET-28a(+) expression system in E. coli BL21(DE3). SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified EstAS showed a single band corresponding to about 31 kDa (Fig. 3), quite agreement with the predicted full length of EstAS. The purity of the purified protein was more than 98% according to SDS-PAGE analysis.

Substrate specificity of EstAS

We expressed EstAS as a hexahistidine-tagged (His-tagged) protein and investigated its chain length specificity using p-nitrophenyl esters (Sigma). EstAS showed high activity towards short-chain fatty acids (C4, C6 and C8), while much lower towards long-chain fatty acids (>C8) (Fig. 4). In addition, EstAS showed no fluorescence on olive oil plates with rhodamine B. Moreover, the EstAS was not able to hydrolyse DGGR (data not shown), while the lipase from Candida rugosa (used as a positive control) was able to hydrolyse DGGR to form chromogenic product, methylresorufin. These results indicate that EstAS is an esterase but a lipase [1, 25, 32, 33].

Substrate specificity of overexpressed and purified esterase. Relative activity was shown as the percentage of the activity towards 4-nitrophenyl hexanoate. All measurements were done in triplicate. C2, p-NP acetate; C4, p-NP butyrate; C6, p-NP hexanoate; C8, p-NP caprylate; C10, p-NP decanoate; C12, p-NP laurate; C14, p-NP myristate and C16, p-NP palmitate.

Effect of temperature and pH on EstAS

Purified esterase EstAS showed a broader temperature range (optimum at 35°C) than other original esterases, and retained over 65% activity at 60°C (Fig. 5). The esterase YlLip2 from Yarrowia lipolytica showed an optimum temperature at 40°C [34], however, it showed a poor thermostability since it lost activity just only incubation at 45°C for 4h. And also, the esterase EstAS showed activity in a rather broad pH range of 5.5-10.5. Maximal activity was observed at pH 9.0 and nearly 23% was still left at pH 10.5 (Fig. 6).

Apparent temperature optimum of esterase EstAS. Relative activity of p-NP-hexanoate hydrolysis at different temperatures by purified EstAS. The activity was determined at different temperatures at pH 8.0 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer. The activity at 35°C was set as 100% (4760 U/ml). All measurements were done in triplicate.

Effect of pH on the purified esterae EstAS. Relative activity of p-NP-hexanoate hydrolysis was performed in various pH buffers at 35°C (pH 5.0-7.5, 50 mM phosphate buffer; pH 8.0-10.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer). The activity at pH 9.0 was set as 100% (4917 U/ml). All measurements were done in triplicate.

Effect of metal ions on esterase EstAS

The effect of metal ions on esterase EstAS activity is depicted in Table 3. Among metal ions tested, the activity was slightly increased by Co2+ (117%), Zn2+ (114%) and Fe2+ (103%), and strongly promoted by 1 mM Mn2+ (190%), in comparison with the control. However, it was a bit inhibited by Mg2+ and Ni2+ and almost totally inhibited by Cu2+ (7% residual activity). The fact that its activity was not affected by the chelating agent EDTA might suggest that this esterase is not a metalloenzyme. These results indicated that divalent metal ions, especially Mn2+, are necessary for the catalytic activity of esterase EstAS, similarly to metagenomic lipase LipG [35] and esterase EstA from marine metagenome [36]. Therefore, manganese ions might carry out three distinct roles in esterase action: removal of fatty acids as insoluble Mn2+ salts in certain cases, direct enzyme activation acting as cofactor, and stabilizing effect on the enzyme.

Effect of detergents and reductors on esterase EstAS

The effects of detergents and reductors on esterase activity are shown in Table 4. A significant increase in lipolytic activity was observed with addition of 0.1% Tween 80 (128%), Tween 20 (135%), and 1 mM CTAB (138%), Triton X-100 (119%), after 0.5 h preincubation at 35°C. 1 mM β-mercaptoethanl, DTT did not affect the lipolytic activity (102% and 101%, respectively). However, DEPC and SDS had a strong inhibitory effect. In accordance with the esterase reported by Nawani et al. [36], a total loss of activity in the presence of SDS but an enhanced activity in the presence of Triton X-100, and Tween 20 and 80. Interesting, the esterase EstAS activity was not affected by 1 mM PMSF, suggesting it may possess a lid structure, which could eliminate the inhibition effect of PMSF, as some other esterases [10, 37, 38] and site-directed mutagenesis of amino acid Ser92 will be carried out to confirm the function of Ser92.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we identified a new esterase EstAS belonging to family III lipases from SBR activated sludge metagenomic library. EstAS is a very interesting enzyme with high potential for downstream biotechnological applications. This was confirmed by extensive biochemical characterization, substrate specificity, stability towards addictives including metal ions and detergents, and also, wide pH and temperature spectra. This study also demonstrated that the metagenomic approach is very useful for expanding our knowledge of enzyme diversity, especially for bacterial esterases. Accessing the metagenomic pool of lipases and esterases can be an immediate source of novel biocatalysts, or yield enzymes that can be further specialized by directed evolution.

References

Jaeger KE, Dijkstra BW, Reetz MT: Bacterial biocatalysts: molecular biology, three-dimensional structures, and biotechnological applications of lipases. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999, 53: 315-351. 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.315.

Jaeger KE, Ransac S, Dijkstra BW, Colson C, Heuvel M van, Misset O: Bacterial lipases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994, 15 (1): 29-63. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00121.x.

Schmid A, Dordick JS, Hauer B, Kiener A, Wubbolts M, Witholt B: Industrial biocatalysis today and tomorrow. Nature. 2001, 409 (6817): 258-268. 10.1038/35051736.

Straathof AJ, Panke S, Schmid A: The production of fine chemicals by biotransformations. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002, 13 (6): 548-556. 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00360-9.

Handelsman J: Metagenomics: Application of genomics to uncultured microorganisms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004, 68 (4): 669-685. 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.669-685.2004.

Lee SW, Won K, Lim HK, Kim JC, Choi GJ, Cho KY: Screening for novel lipolytic enzymes from uncultured soil microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004, 65 (6): 720-726. 10.1007/s00253-004-1722-3.

Elend C, Schmeisser C, Leggewie C, Babiak P, Carballeira JD, Steele HL, Reymond JL, Jaeger KE, Streit WR: Isolation and biochemical characterization of two novel metagenome-derived esterases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72 (5): 3637-3645. 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3637-3645.2006.

Henne A, Schmitz RA, Bomeke M, Gottschalk G, Daniel R: Screening of environmental DNA libraries for the presence of genes conferring lipolytic activity on Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000, 66 (7): 3113-3116. 10.1128/AEM.66.7.3113-3116.2000.

Li G, Wang K, Liu YH: Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel pyrethroid-hydrolyzing esterase originating from the metagenome. Microb Cell Fact. 2008, 7 (38):

Chu XM, He HZ, Guo CQ, Sun BL: Identification of two novel esterases from a marine metagenomic library derived from South China Sea. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008, 80 (4): 615-625. 10.1007/s00253-008-1566-3.

Jeon JH, Kim JT, Kim YJ, Kim HK, Lee HS, Kang SG, Kim SJ, Lee JH: Cloning and characterization of a new cold-active lipase from a deep-sea sediment metagenome. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009, 81 (5): 865-874. 10.1007/s00253-008-1656-2.

Park HJ, Jeon JH, Kang SG, Lee JH, Lee SA, Kim HK: Functional expression and refolding of new alkaline esterase, EM2L8 from deep-sea sediment metagenome. Prot Expr Purif. 2007, 52 (2): 340-347. 10.1016/j.pep.2006.10.010.

Ranjan R, Grover A, Kapardar RK, Sharma R: Isolation of novel lipolytic genes from uncultured bacteria of pond water. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005, 335 (1): 57-65. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.046.

Rees HC, Grant S, Jones B, Grant WD, Heaphy S: Detecting cellulase and esterase enzyme activities encoded by novel genes present in environmental DNA libraries. Extremophiles. 2003, 7 (5): 415-421. 10.1007/s00792-003-0339-2.

Rhee JK, Ahn DG, Kim YG, Oh JW: New thermophilic and thermostable esterase with sequence similarity to the hormone-sensitive lipase family, cloned from a metagenomic library. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71 (2): 817-825. 10.1128/AEM.71.2.817-825.2005.

Wu C, Sun BL: Identification of novel esterase from metagenomic library of Yangtze River. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009, 19 (2): 187-193. 10.4014/jmb.0804.292.

Sambrook J, Russell DW: Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2001, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York

Birnboim HC, Doly J: A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979, 7 (6): 1513-1523. 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513.

Zhou J, Bruns MA, Tiedje JM: DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996, 62 (2): 316-322.

Xi F, Fu LY, Wang GZ, Zheng TL: A simple method for removing humic acids from marine sediment samples prior to DNA extraction. Chin High Technol Lett. 2006, 16 (5): 539-544.

Roh C, Villatte F: Isolation of a low-temperature adapted lipolytic enzyme from uncultivated microorganism. J Appl Microbiol. 2008, 105 (1): 116-123. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03717.x.

Saitou N, Nei M: The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987, 4 (4): 406-425.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG: The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25 (24): 4876-4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876.

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007, 24 (8): 1596-1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092.

Hardeman F, Sjoling S: Metagenomic approach for the isolation of a novel low-temperature-active lipase from uncultured bacteria of marine sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007, 59 (2): 524-534. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00206.x.

Jiang HF, Wang YQ, Liu CG: Comparison and improvement of three determination methods for lipase activity. Chem Eng. 2007, 24 (8): 72-75.

Pignede G, Wang HJ, Fudalej F, Gaillardin C, Seman M, Nicaud JM: Characterization of an extracellular lipase encoded by LIP2 in Yarrowia lipolytica. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182 (10): 2802-2810. 10.1128/JB.182.10.2802-2810.2000.

Panteghini M, Bonora R, Pagani F: Measurement of pancreatic lipase activity in serum by a kinetic colorimetric assay using a new chromogenic substrate. Ann Clin Biochem. 2001, 38 (4): 365-370. 10.1258/0004563011900876.

Zandonella G, Haalck L, Spener F, Faber K, Paltauf F, Hermetter A: Enantiomeric perylene-glycerolipids as fluorogenic substrates for a dual wavelength assay of lipase activity and stereoselectivity. Chirality. 1996, 8 (7): 481-489. 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1996)8:7<481::AID-CHIR4>3.0.CO;2-E.

Ollis DL, Cheah E, Cygler M, Dijkstra B, Frolow F, Franken SM, Harel M, Remington SJ, Silman I, Schrag J, Sussman JL, Verschueren KHG, Goldman A: The alpha/beta-hydrolase Fold. Protein Eng. 1992, 5 (3): 197-211. 10.1093/protein/5.3.197.

Bell PJL, Sunna A, Gibbs MD, Curach NC, Nevalainen H, Bergquist PL: Prospecting for novel lipase genes using PCR. Microbiology-Sgm. 2002, 148 (8): 2283-2291.

Verger R: Interfacial activation of lipases: Facts and artifacts. Trends Biotechnol. 1997, 15 (1): 32-38. 10.1016/S0167-7799(96)10064-0.

Jaeger KE, Eggert T: Lipases for biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002, 13 (4): 390-397. 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00341-5.

Yu MR, Qin SW, Tan TW: Purification and characterization of the extracellular lipase Lip2 from Yarrowia lipolytica. Process Biochem. 2007, 42 (3): 384-391. 10.1016/j.procbio.2006.09.019.

Lee MH, Lee CH, Oh TK, Song JK, Yoon JH: Isolation and characterization of a novel lipase from a metagenomic library of tidal flat sediments: evidence for a new family of bacterial lipases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72 (11): 7406-7409. 10.1128/AEM.01157-06.

Nawani N, Dosanjh NS, Kaur J: A novel thermostable lipase from a thermophilic Bacillus sp.: Characterization and esterification studies. Biotechnol Lett. 1998, 20 (10): 997-1000. 10.1023/A:1005430215849. 10.1023/A:1005430215849.

De Simone G, Menchise V, Manco G, Mandrich L, Sorrentino N, Lang D, Rossi M, Pedone C: The crystal structure of a hyper-thermophilic carboxylesterase from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. J Mol Biol. 2001, 314 (3): 507-518. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5152.

De Simone G, Galdiero S, Manco G, Lang D, Rossi M, Pedone C: A snapshot of a transition state analogue of a novel thermophilic esterase belonging to the subfamily of mammalian hormone-sensitive lipase. J Mol Biol. 2000, 303 (5): 385-10.1006/jmbi.2000.4195. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4195.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants of Hi-Tech Research and Development Program of China ("863" program, No. 2006AA06Z316) and the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. KJCX2-YW-L08 and KSCS2-YW-G-055-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TZ participated in the design of experiments, and carried out the study and drafted the manuscript. WJH carried out the SDS-PAGE experiment and sequence alignment. ZPL conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Tao Zhang, Wen-Jun Han contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Han, WJ. & Liu, ZP. Gene cloning and characterization of a novel esterase from activated sludge metagenome. Microb Cell Fact 8, 67 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-8-67

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-8-67