Abstract

Background

The genome of the important industrial host Bacillus subtilis does not encode the glyoxylate shunt, which is necessary to utilize overflow metabolites, like acetate or acetoin, as carbon source. In this study, the operon encoding the isocitrate lyase (aceB) and malate synthase (aceA) from Bacillus licheniformis was transferred into the chromosome of B. subtilis. The resulting strain was examined in respect to growth characteristics and qualities as an expression host.

Results

Our results show that the modified B. subtilis strain is able to grow on the C2 compound acetate. A combined transcript, protein and metabolite analysis indicated a functional expression of the native glyoxylate shunt of B. lichenifomis in B. subtilis. This metabolically engineered strain revealed better growth behavior and an improved activity of an acetoin-controlled expression system.

Conclusions

The glyoxylate shunt of B. licheniformis can be functionally transferred to B. subtilis. This novel strain offers improved properties for industrial applications, such as growth on additional carbon sources and a greater robustness towards excess glucose feeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

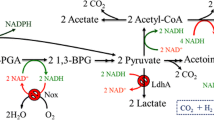

The anaplerotic glyoxylate cycle is a variation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle), which allows acetyl-CoA to be used to replenish carbon for anabolic processes [1]. The isocitrate lyase of this shunt prevents a carbon loss by cleaving isocitrate into glyoxylate and succinate, thus avoiding the decarboxylation of isocitrate and 2-oxoglutarate. Glyoxylate and acetyl-CoA are joined to malate by the malate synthase, the second enzyme of the glyoxylate shunt, which allows for the regeneration of oxaloacetate that is henceforth available for anabolic activities via the TCA cycle or gluconeogenesis. From a bioprocessing viewpoint, this ability is especially interesting for bacteria that previously produced overflow metabolites. In terms of Bacillus subtilis such conditions include aerobic growth with excess glucose or anaerobic nitrate respiration [2, 3] and lead to the formation of acetate as well as acetoin and 2,3-butanediol. Industrial fermentation processes are usually so designed that overflow metabolism is avoided or at least limited. The overflow metabolism leads to metabolic shifts towards less efficient pathways and causes energy spilling reactions [3]. Nevertheless the mixing of incoming, highly concentrated feed solutions is insufficient in industrial-scale bioreactors and always gives rise to zones of excess carbon source [4]. For Escherichia coli it has been shown that the formation of overflow metabolites, especially acetate, hampers large scale fed-batch processes. Accumulated acetate has been observed to have adverse effects on target product formation and cell growth [5].

After depletion of the preferred carbon source (e.g. glucose), the excreted overflow metabolites are converted into metabolically utilizable acetyl-CoA [6]. Since B. subtilis lacks the capability to conduct the glyoxylate cycle, it can only make use of the energy provided by the overflow metabolites in the form of reduction equivalents, which are generated during the TCA cycle. In this study the transfer of the glyoxylate shunt - operon from its close relative Bacillus licheniformis[7] was investigated in B. subtilis. It is shown that the functional expression of this operon enables B. subtilis to utilize the overflow metabolite acetate as a carbon source and resulted in a more robust growth behavior with excess glucose and an increased production of a recombinant reporter enzyme.

Results

Primer extension experiments with B. licheniformis showed that the transcript of the glyoxylate operon (aceBA) starts 231 bp upstream of the aceB gene with a potential promoter sequence at the position of 4,040,629 to 4,040,601 in the genome (personal communication A. Ehrenreich). Analysis of the 3’-end with the Vienna RNA package [8] revealed a potential terminator structure (4,037,415 to 4,037,434; –∆G = 15.2) and typical Shine-Dalgarno sequences (SDS) in front of a hypothetical protein sequence (RBS1: 4,040,515 to 4,038,510), aceB (RBS2: 4,040,338 to 4,040,332) and aceA (RBS3: 4,038,731 to 4,038,726) (Figure 1A). These SDS meet the requirements for an efficient ribosomal binding side of B. subtilis[9].

Structure of the aceBA-operon of B. licheniformis (A) and schematic representation of its transfer into the B. subtilis genome (B). (A) The aceBA-operon of B. licheniformis DSM13 encodes the malate synthase (aceB), the isocitrate lyase (aceA) and a hypothetical protein which is essential for the functional transfer of this operon in B. subtilis. (RBS: ribosome binding site). (B) In a first step, the aceB and aceA genes without a promoter but a neomycin resistance cassette (NeoR) were integrated into the chromosomal amyE-locus of B. subtilis by a double cross-over event. In a second step the resulting strain was transformed with a DNA-fragment containing the gene of the hypothetical protein and the native promoter of the aceBA-operon by selecting on the erythromycin resistance cassette (EryR).

First attempts to construct plasmids containing the complete glyoxylate operon of B. licheniformis failed with E. coli as subcloning host. Transformation of the ligation reaction using E. coli as a shuttle host resulted in plasmids containing different fragments of the genes, but never the complete operon, making it likely that ORFs of the glyoxylate operon are expressed in E. coli and interfere with its metabolism. Therefore, we constructed the plasmids in such a manner that one plasmid contained only the aceB and the aceA genes without a promoter and another plasmid contained the native aceBA-operon specific promoter and the above mentioned hypothetical protein (Figure 1B). Both plasmids could be propagated in E. coli and the transformation of B. subtilis in a two-step-procedure worked well, yielding B. subtilis ACE which contains the native glyoxylate operon of B. licheniformis in its chromosomal amyE locus.

In mineral salt medium containing a mixture of glycerol, acetate and acetoin as carbon sources, the glyoxylate-positive strain B. subtilis ACE reached a significantly higher final maximal optical density than the wild type strain (Figure 2). Glycerol is in this medium the preferred carbon and energy source for B. subtilis. In contrast to the wild type (WT) B. subtilis ACE showed a diauxic growth pattern with a slightly reduced specific growth rate during the mid-exponential growth phase, indicating a utilization of acetate but also acetoin for its growth.

A quantitative aceB-mRNA-analysis indicated a basal expression of the aceBA-operon in B. subtilis ACE during the exponential growth on glycerol (Figure 3). A significant induction (~7-fold) occurred during the diauxic transition phase. The B. subtilis control strain (WT) did not show a detectable aceB-mRNA signal in any of the experiments (data not shown). The expression of the isocitrate lyase (AceA) in the aceBA positive strain was detectable in the cytoplasmic soluble proteome during the transient and stationary phase by mass spectrometry analyses. No AceA-specific peptides could be identified in the negative control (WT). However, no peptides could be detected for the malate synthase (AceB) and the hypothetical protein in any of the samples. The difficulty of the identification of AceB-specific peptides was not unexpected, since the protein has so far eluded identification in several gel-based studies of B. licheniformis (personal communication B. Voigt, [10]). With a molecular weight of about 5 kDa, the absence of peptides for the hypothetical protein can be explained by the difficulties of analyzing such small proteins with the gel-based MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

aceB- mRNA quantification by real-time-RT-PCR. The length of the detected aceB-transcript was 300 nucleotides. ACE = B. subtilis encoding the aceBA-operon. t1-t4 sampling points throughout the growth curve as shown in Figure 2. N = 3, therefore the box plot does not show quartils.

The analysis of extracellular metabolites revealed the consumption of glycerol as the preferred carbon source and a nearly constant level of acetoin and acetate during this first growth phase (Figure 4). Thus, in contrast to growth on glucose [6, 11], B. subtilis does not produce overflow metabolites like acetate or acetoin in detectable amounts while using glycerol as main carbon source. Both strains showed a weak utilization of acetate and acetoin already during the late exponential growth phase on glycerol. However, the glyoxylate cyle - positive ACE strain revealed a significant higher utilization of acetate but also of acetoin compared to the WT. After exhaustion of glycerol the ACE strain started to accumulate glycolic acid. In contrast, no such accumulation could be detected in the B. subtilis WT strain. It is interesting to note that the final glycolic acid concentration in the B. subtilis ACE mutant strain was almost three times as high as that of the aceBA-donor strain B. licheniformis DSM13 (data not shown). Glyoxylate could not be detected in the supernatant of any strain. 2.3-butanediol accumulated in both B. subtilis strains and was not consumed (Figure 4).

Quantification of selected extracellular metabolites. 1H-NMR-quantified metabolites of the added carbon sources and selected byproducts of the B. subtilis wild type (WT) and the B. subtilis ACE strain with the glyoxylate cycle operon (ACE). The corresponding sampling points are indicated in Figure 2.

Simulated fed-batch cultivation experiments using ‘EnBase Flo’ revealed a clear distinction of growth patterns between the WT and the glyxolate cycle - positive mutant (Figure 5). B. subtilis ACE reached higher cell densities and was not negatively affected by the addition of excess glucose. In contrast, the WT only exhibited a relative stable growth behavior without additional glucose. The excess of glucose led to a lysis of the WT cells after 360 min of incubation. All cultures, except the WT cultures with 0.2 or 0.4% glucose, featured a pronounced biofilm formation in the late growth phase (at about 1200 min). Additionally, B. subtilis ACE produced a red pigment, which was not detectable in the WT cultures. The formation of biofilms and pigments hampered the exact determination of the optical density in these experiments. However, the determined trend in the growth behavior was reproducible for all investigated biological replicates. The absorption maximum of the observed red pigment in these cultures was at 410 nm, while only a minor absorption could be observed at 500 nm [12]. Care was as well taken not to pipette the biofilm but only the cells underneath. It should be noted that due to different path lengths and measurement methods of the plate reader in comparison to a standard photometer, OD values shown in Figure 5 are relative values. The final ODs of the cultures measured with a standard 1 cm path length photometer are given in the legend of Figure 5.

Simulated of fed-batch and high glucose conditions with EnBase Flo. Wild type = B. subtilis ΔamyE; B. subtilis ACE = glyoxylate cycle - positive mutant with the aceBA-operon integrated into the amyE-locus. The final optical densities (OD) were measured with a 1 cm path length cuvette with the following results: WT 0% glucose = 8.77; WT 0.2% glucose = 2.05; WT 0.4% glucose = 1.85; ACE 0% glucose = 15.18; ACE 0.2% glucose = 16.16; ACE 0.4% glucose = 16.84.

In order to further characterize the glyoxylate shunt - expressing B. subtilis strain, studies using an acetoin-inducible promoter (acoA) and a secreted alpha-amylase [13] as a reporter enzyme were carried out. In order to increase the transcription activity of the acoA-promoter the MSM growth medium was supplemented with 0.5% acetoin. Similar to the growth experiments shown in Figure 2 the ACE-strain revealed a higher final optical density in comparison to the WT (Figure 6). It is interesting to note that the B. subtilis ACE strain enables an increased acoA-directed amylase overproduction under these conditions. These experiments also indicate that the acoA-promoter is repressed during growth on glycerol [14] and is activated during the transient phase in the WT culture and during growth on acetate in the B. subtilis ACE strain after glycerol has been consumed.

Influence of the glyoxylate shunt on the acoA -controlled amylase overproduction of B. subtilis ACE compared to the WT. In both strains the native alpha-amylase gene was disrupted and a functional copy under control of the acoA-promoter was integrated into the sacA-locus. Exact sampling points for activity measurements are indicated in small type. Medium: MSM + 0.5% acetate, 0.08% glycerol, 0.5% acetoin.

Discussion

Relatively little is known about the regulation of the glyoxylate cycle in Gram-positive bacteria. Results of this study indicate a control of the aceBA-operon of B. licheniformis in B. subtilis at the transcriptional level. A transcriptional regulation of the glyoxylate shunt has also been shown for the Gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum, where the expression of the malate synthase and isocitrate lyase is positively controlled by the LuxR-type transcriptional regulator RamA in the presence of acetate [15]. Voigt et al. detected a strong induction of the AceB expression in B. licheniformis at the transcriptional and translational level as soon as the preferred carbon and energy source glucose is exhausted [16]. Schroeter et al. [10] could determine an induction of the glyoxylate shunt during peroxide stress experiments, which was attributed to an irreversible oxidation of the isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH). However, it is also shown in our study that the region encoding the hypothetical protein (BL02643) in front of aceBA is essential for a functional transfer of the glyoxylate shunt to B. subtilis. Strain constructs missing this putative regulatory region of the operon fail to grow on acetate (data not shown). It can be concluded that this small protein plays an essential role in the regulation of the glyoxylate cycle activity.

The incorporation of the glyoxylate shunt - encoding operon led to growth of B. subtilis ACE on the overflow metabolite acetate and to a lesser degree on acetoin. A diauxic growth with a preferred utilization of glycerol over acetate can be derived from the metabolite analyses (Figure 4). However, the current version of the glyoxylate cycle - positive strain B. subtilis ACE failed to reach the same maximal optical density as B. licheniformis (data not shown). A possible reason for its earlier growth arrest might be the accumulation of glycolic acid (see Figure 4). This small alpha-hydroxy acid has been described as a potent inhibitor of the isocitrate lyase of Pseudomonas indigofera[17] and could disable B. subtilis ACE to continue utilizing acetate as a replenishing carbon source through its glyoxylate cycle. Glycolic acid is also formed in B. licheniformis, but to a much smaller extent (data not shown). B. licheniformis DSM13 possesses a putative glyoxylate reductase (ORF BL02138) which exhibits a 70% identity to a similar enzyme (gyaR) of Bacillus pumilus ATCC 7061. This putative glyoxylate reductase (ORF BL02138) could catalyze the reduction of glyoxylate to glycolic acid and could thus lead to a reduced accumulation of glycolic acid in B. licheniformis.

The accumulation of 2.3-butanediol in B. subtilis during the exponential and stationary phase is likely due to the activity of the acetoin reductase/2.3-butanediol dehydrogenase (bdhA) [18]. The remaining acetoin could block the reverse reaction that would transform the 2.3-butanediol back to acetoin. It has been reported that the presence of acetic acid leads to an increased production of 2.3-butanediol by B. subtilis[19]. In contrast, B. licheniformis is able to utilize acetoin but also 2.3-butanediol entirely (data not shown), which might also have contributed to an increase of biomass. This is most probably also supported by the butanediol/acetoin reductase encoded by the budC (BL01177) gene of B. licheniformis, which catalyzes the irreversible reduction of 2.3-butanediol to acetoin [20]. Interestingly, the subspecies B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii, which is of a different lineage than the used B. subtilis strain 6051HGW [21], encodes the same potential for the 2.3-butanediol utilization as B. licheniformis, highlighting both as potential donors of the butanediol/acetoin reductase for a further optimization of B. subtilis ACE.

The simulated EnBase fed-batch cultivation indicated an advantage of the glyoxylate shunt - active strain B. subtilis ACE in comparison to the WT under high glucose concentration conditions. Induction of a significant overflow metabolism by addition of excess glucose presumably resulted in the growth arrest of the WT, while the activity of the glyoxylate shunt enabled B. subtilis ACE to exploit too high levels of these metabolites and to reach thus elevated cell densities.

This study indicates that the previously described acoA-expression system [13] displays an improved performance in the glyoxylate cycle - positive strain B. subtilis ACE. The promoter of the acoABCL-operon is repressed by PTS–sugars [22], but as demonstrated in this study also by the non-PTS carbon source glycerol. The cheap C-source glycerol in combination with acetate therefore offers an interesting alternative for the control of the acoA-based B. subtilis expression system. Another possible application of B. subtilis ACE may be an auto-inducing system that depends on phosphate limitation. As described by Dauner et al.[3], B. subtilis produces large quantities of acetate during chemostat experiments with high glucose and low phosphate levels. The ability of B. subtilis ACE to produce higher recombinant target protein levels, while growing on acetate, would therefore be a suitable alternative possibility for the application of the acoA-expression system.

Conclusion

The aceBA operon of B. licheniformis is a self-contained metabolic entity that can be functionally transferred to B. subtilis. The obtained strain is able to grow on acetate as carbon source which results in an increased biomass formation and an improved production of a recombinant model protein. In addition, the glyoxylate cycle-positive B. subtilis mutant cells feature greater robustness towards excess glucose cultivations.

Methods

Construction of plasmids, strains, and genome analysis

Chromosomal DNA of Bacillus licheniformis MW3, which is a mutant of B. licheniformis DSM13 [23], was used as template for the amplification of the aceBA-operon. Sequence information was derived from the published genome of B. licheniformis DSM13 [GenBank:NC_006322]. PCRs were performed with the Phusion polymerase. The utilized oligonucleotides are summarized in Table 1, while the constructed plasmids and used strains are listed in Table 2.

The plasmid pACEBA was constructed by amplifying the aceBA-operon without its predicted promoter region and the hypothetical protein. The PCR product and the pBGAB [26] plasmid were cut with XbaI and BamHI and ligated using T4-ligase. To integrate the native promoter and the hypothetical protein in front of the aceBA-operon, the pBGAG plasmid was cut with SmaI and NotI and an erythromycin cassette from pMTL500 [27] was inserted yielding the plasmid pAMYSSE. Hereafter, this plasmid was cut with NarI and EcoRI and the PCR product resulting from the Prom1-primer pair was integrated via a modified sequence and ligation-independent cloning method [24]. Electroporation of the plasmids into E. coli was performed as previously described [28]. All utilized enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt a. M., Germany), oligonucleotides were synthesized by Life Technologies (Darmstadt, Germany).

To obtain an aceBA-encoding strain, B. subtilis 60-51HGW was transformed via natural competence [29] using the linearized plasmid pACEBA. The clones were selected on neomycin and the positive mutants were designated as B. subtilis ACE-P. To functionalize the operon, pProm1 was transformed in the same manner into B. subtilis ACE-P with erythromycin selection resulting in B. subtilis ACE. To examine the expression of a reporter enzyme, B. subtilis ACE and B. subtilis 6051HGW were transformed with pSacAmyE yielding a wild type (B. subtilis WTamyE) and a glyoxylate cycle - positive mutant (B. subtilis ACEamyE) that express and secrete an alpha-amylase under control of the acoA-promoter [13]. pSacAmyE was constructed by cutting pJK168 and pMJS2 [13] with XbaI and ligating the acoA-amyE fragment from pMJS2 into the sacA landing pads of pJK168. To ensure comparable alpha-amylase measurements, the native alpha-amylase of B. subtilis was disrupted by the integration of the aceBA- operon (B. subtilis ACEamyE) and an erythromycin cassette of plasmid pAMYSSE (B. subtilis WTamyE) into the amyE-locus. All plasmid constructs and chromosomal integrations were verified by sequencing.

The publicly available genome sequence of B. licheniformis was annotated in 2004 [7]. Since then, a large amount of novel sequences and annotations have been published, which implicates the necessity to update previous functional assignments for organisms of interest. Accordingly, we reannotated the genome sequence of B. licheniformis DSM13 in the same manner as described for B. subtilis 6051HGW [24]. In short, the GenBank file of B. licheniformis DSM13 [GenBank:AE017333] was imported into the GenDB 2.2 [30] pipeline and the resulting database was used to analyze the ORFs with JCoast [31].

Cultivation conditions

Cultivations were carried out at 37°C and 250 rpm shaking in Erlenmeyer flasks with a maximum culture volume of one fifth of the flasks volume. Pre-cultures were inoculated from a cryo-stock and grown in LB medium for 5 h and then transferred into the appropriate medium for overnight cultures. Main cultures were inoculated from exponentially growing overnight cultures. The composition of the mineral salt medium (MSM) and its trace element solution has been described previously [24]. The MSM was supplemented with 0.08% glycerol, 0.5% acetate, 0.2% acetoin, and 2 mM MgSO4 if not indicated otherwise.

In order to test fed-batch like conditions, we cultivated the glyoxylate cycle - positive mutant and the WT strain with 3 ml EnBase Flo Liquid (# EBLM500, BioSilta Oy, Oulu, Finland) medium in 24-deep-well plates. The EnBase system is based on the slow release of glucose from a polymer through the action of an enzyme, thus acting like a substrate feeding pump [32]. The native amylase of B. subtilis (amyE) has been reported to interfere with this method (personal communication P. Neubauer). Therefore, B. subtilis amylase knock-out strains (Table 2) were used in all EnBase cultivations. Beside the control culture without external glucose addition, cultures supplemented with 0.2% and 0.4% glucose were investigated to simulate high glucose conditions and to stimulate acetate formation. 1.5 U of the EnBase-specific hydrolase (BioSilta Oy, Oulu, Finland) was used in all experiments. Plates were shaken at 300 rpm with an amplitude of 25 mm. Sample volume was 10 μl, with which the OD at 500 nm was determined in a 1:10 dilution in a Tecan infinite M200 plate reader (Männerdorf, CH).

RNA analysis

RNA samples were taken and prepared as previously described [33]. An additional treatment with RNAse-free DNAse (#79254, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was performed followed by a purification with the RNA Clean-Up and Concentration Kit (#23600) from Norgen Biotek (Thorold, Canada).

The aceB-mRNA-standard was created with the primers aceB-for and aceB-rev-T7 (Table 1) using the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (SP6/T7) from Roche (Mannheim, Germany) and substituting the DIG-labeled nucleotides with unlabeled NTPs (Fermentas UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania).

The real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed as described by Hoi et al. [34]. The RNA samples were prepared as recommended by the supplier of the LightCycler® RNA Master SYBR Green I (#03064760001, Roche). The RT-PCR reaction was prepared with the primers aceB-for and aceB-rev (Table 1) and analyzed applying the Roche LightCycler as suggested by the manufacturer with an annealing temperature of 56°C.

Protein analysis

The supernatant required for the alpha-amylase reporter enzyme assay was obtained by centrifugation of 2 ml culture at 10000 x g for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a new tube and stored at -20°C until further processing. The amylase activity was determined by use of the Ceralpha Assay (Megazymes, Wicklow, Ireland). To stay within the linear range, 1:200 dilutions in the suggested buffer were prepared. Measurements were done with a Tecan infinite M200 plate reader.

For the cytosolic proteome analysis, 8 ml of cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with TE-buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) and finally resuspended in 1 ml TE with 2 mM PMSF (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Samples were transferred to cryotubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) filled with 0.25 ml glass beads (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) and the cells were disrupted by bead-beating for 30 seconds at 6.5 m/s. After cooling for 5 min on ice, this procedure was repeated twice. Cell debris was removed by 30 min centrifugation at 17000 x g. The supernatant was stored at -20°C. 5 μg of protein mixture were separated by SDS-PAGE [35] and stained with silver-blue Coomassie [36].

The bands were excised using a sterile scalpel and transferred into 96 well micro titer plates (Greiner bio one, Frickenhausen, Germany). The tryptic digest with subsequent spotting on a MALDI-target was carried out automatically with the Ettan Spot Handling Workstation (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The gel pieces were washed twice with 100 μl of a solution of 50% CH3OH and 0% 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 30 min and once with 100 μl 75% CH3CN for 10 min. After drying at 37°C for 17 min 10 μl trypsin solution containing 4 μg/ml trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added and incubated at 37°C for 120 min. For extraction gel pieces were covered with 60 μl 0.1% TFA in 50% CH3CN and incubated for 30 min at 40°C. The peptide-containing supernatant was transferred into a new microtiter plate and the extraction was repeated with 40 μl of the same solution. The supernatants were completely dried at 40°C for 220 min. The dry residue was resuspended in 0.9 μl α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid matrix (3.3 mg/ml in 50%/49.5%/0.5% (v/v/v) CH3CN/H2O/TFA) and 0.7 μl of this solution was deposited on the MALDI target plate. The samples were allowed to dry on the target 10 to 15 min before measurement by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

The MALDI-TOF measurement was carried out on the AB SCIEX TOF/TOF™ 5800 Analyzer (ABSciex /MDS Analytical Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). This instrument is designed for high throughput measurement, being automatically able to measure the samples, calibrate the spectra and analyze the data using the TOF/TOF™ Series Explorer™ SoftwareV4.1.0. The spectra were recorded in a mass range from 900 to 3700 Da with a focus mass of 1700 Da. For one main spectrum 25 sub-spectra with 100 shots per sub-spectrum were accumulated using a random search pattern. If the autolytical fragment of trypsin with the mono-isotopic (M + H) + m/z at 2211.104 reached a signal to noise ratio (S/N) of at least 40, an internal calibration was automatically performed as one-point-calibration using this peak. The standard mass deviation was less than 0.15 Da. If the automatic mode failed (in less than 1%), the calibration was carried out manually. The five most intense peaks from the TOF-spectra were selected for MS/MS analysis. For one main spectrum 20 sub-spectra with 125 shots per sub-spectrum were accumulated using a random search pattern. The internal calibration was automatically performed as one-point-calibration with the mono-isotopic arginine (M + H) + m/z at 175,119 or Lysine (M + H) + m/z at 147,107 reached a signal to noise ratio (S/N) of at least 5. The peak lists were created by using GPS Explorer™ Software Version 3.6 (build 332) with the following settings for TOF-MS: mass range, 900–3700 Da; peak density, 20 peaks per 200 Da; minimum S/N ratio of 15 and maximal 65 peaks per spot. The TOF-TOF-MS settings were a mass range from 60 to Precursor - 20 Da; a peak density of 50 peaks per 200 Da and maximal 65 peaks per precursor. The peak list was created for an S/N ratio of 10. All peak lists were analysed using Mascot search engine version 2.4.0 (Matrix Science Ltd, London, UK) with a specific user sequence database and specific B. subtilis and B. licheniformis databases.

1H-NMR for extracellular metabolite analysis

2 ml cell culture was rapidly sterile filtered into a 2 ml tube and stored at -20°C. 400 μl of the extracellular sample was buffered to pH 7.0 by addition of 200 μl of a sodium hydrogen phosphate buffer (0.2 mM [pH 7.0], including 1 mM TSP)) made up with 50% D2O to provide a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-lock signal. The samples were measured using 1H-NMR (600.27 MHz) at a nominal temperature of 310 K (Bruker AVANCE-II 600 NMR spectrometer, Bruker Biospin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) as described previously [37]. AMIX 3.9 was used for data processing and analysis.

Software

Graphs were created using R [38] and, where applicable, with the ggplot2 package [39]. Graphs for metabolites were created with VANTED V2.1.3 [40]. Genome analysis was done with Geneious version 5.6.2 created by Biomatters (Auckland, NZ) available from http://www.geneious.com. Free Gibbs-Energy (-∆G) of mRNA structures was determined with UNAfold [41].

References

Kornberg HL, Krebs HA: Synthesis of cell constituents from C2-units by a modified tricarboxylic acid cycle. Nature. 1957, 179 (4568): 988-991. 10.1038/179988a0

Hoffmann T, Frankenberg N, Marino M, Jahn D: Ammonification in Bacillus subtilis utilizing dissimilatory nitrite reductase is dependent on resDE. J Bacteriol. 1998, 180 (1): 186-189.

Dauner M, Storni T, Sauer U: Bacillus subtilis metabolism and energetics in carbon-limited and excess-carbon chemostat culture. J Bacteriol. 2001, 183 (24): 7308-7317. 10.1128/JB.183.24.7308-7317.2001

Enfors SO, Jahic M, Rozkov A, Xu B, Hecker M, Jurgen B, Kruger E, Schweder T, Hamer G, O’Beirne D, et al: Physiological responses to mixing in large scale bioreactors. J Biotechnol. 2001, 85 (2): 175-185. 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00365-5

Nakano K, Rischke M, Sato S, Markl H: Influence of acetic acid on the growth of Escherichia coli K12 during high-cell-density cultivation in a dialysis reactor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997, 48 (5): 597-601. 10.1007/s002530051101

Speck EL, Freese E: Control of metabolite secretion in Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1973, 78 (2): 261-275. 10.1099/00221287-78-2-261

Veith B, Herzberg C, Steckel S, Feesche J, Maurer KH, Ehrenreich P, Bäumer S, Henne A, Liesegang H, Merkl R, et al: The complete genome sequence of Bacillus licheniformis DSM13, an organism with great industrial potential. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004, 7 (4): 204-211. 10.1159/000079829

Hofacker IL: RNA secondary structure analysis using the Vienna RNA package. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009, 26: 12.2.1-12.2.16.

Vellanoweth RL, Rabinowitz JC: The influence of ribosome-binding-site elements on translational efficiency in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 1992, 6 (9): 1105-1114. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01548.x

Schroeter R, Voigt B, Jürgen B, Methling K, Pöther DC, Schafer H, Albrecht D, Mostertz J, Mäder U, Evers S, et al: The peroxide stress response of Bacillus licheniformis. Proteomics. 2011, 11 (14): 2851-2866. 10.1002/pmic.201000461

Thanh TN, Jürgen B, Bauch M, Liebeke M, Lalk M, Ehrenreich A, Evers S, Maurer K-H, Antelmann H, Ernst F, et al: Regulation of acetoin and 2, 3-butanediol utilization in Bacillus licheniformis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010, 87 (6): 2227-2235. 10.1007/s00253-010-2681-5

Canale-Parola E: A Red pigment produced by aerobic sporeforming bacteria. Arch Mikrobiol. 1963, 46 (4): 414-10.1007/BF00408495. 10.1007/BF00408495

Silbersack J, Jürgen B, Hecker M, Schneidinger B, Schmuck R, Schweder T: An acetoin-regulated expression system of Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006, 73 (4): 895-903. 10.1007/s00253-006-0549-5

Fujita Y: Carbon catabolite control of the metabolic network in Bacillus subtilis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009, 73 (2): 245-259. 10.1271/bbb.80479

Maeda T, Wachi M: 3’ Untranslated region-dependent degradation of the aceA mRNA, encoding the glyoxylate cycle enzyme isocitrate lyase, by RNase E/G in corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012, 78 (24): 8753-8761. 10.1128/AEM.02304-12

Voigt B, Hoi LT, Jürgen B, Albrecht D, Ehrenreich A, Veith B, Evers S, Maurer K-H, Hecker M, Schweder T: The glucose and nitrogen starvation response of Bacillus licheniformis. Proteomics. 2007, 7 (3): 413-423. 10.1002/pmic.200600556

McFadden BA, Howes WV: Crystallization and some properties of isocitrate lyase from Pseudomonas indigofera. J Biol Chem. 1963, 238 (5): 1737-

Nicholson WL: The Bacillus subtilis ydjL (bdhA) gene encodes acetoin reductase/2, 3-butanediol dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008, 74 (22): 6832-6838. 10.1128/AEM.00881-08

Biswas R, Yamaoka M, Nakayama H, Kondo T, Yoshida K, Bisaria VS, Kondo A: Enhanced production of 2, 3-butanediol by engineered Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012, 94 (3): 651-658. 10.1007/s00253-011-3774-5

Hohn-Bentz H, Radler F: Bacterial 2, 3-butanediol dehydrogenases. Arch Microbiol. 1978, 116 (2): 197-203. 10.1007/BF00406037

Zeigler DR, Prágai Z, Rodriguez S, Chevreux B, Muffler A, Albert T, Bai R, Wyss M, Perkins JB: The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190 (21): 6983-6995. 10.1128/JB.00722-08

Postma P, Lengeler J, Jacobson G: Phosphoenolpyruvate: carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993, 57 (3): 543-

Waschkau B, Waldeck J, Wieland S, Eichstädt R, Meinhardt F: Generation of readily transformable Bacillus licheniformis mutants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008, 78 (1): 181-188. 10.1007/s00253-007-1278-0

Kabisch J, Thurmer A, Hubel T, Popper L, Daniel R, Schweder T: Characterization and optimization of Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 as an expression host. J Biotechnol. 2012, 163 (2): 97-104.

Grant SG, Jessee J, Bloom FR, Hanahan D: Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990, 87 (12): 4645-4649. 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645

Mogk A, Hayward R, Schumann W: Integrative vectors for constructing single-copy transcriptional fusions between Bacillus subtilis promoters and various reporter genes encoding heat-stable enzymes. Gene. 1996, 182 (1–2): 33-36.

Swinfield TJ, Janniere L, Ehrlich SD, Minton NP: Characterization of a region of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAM beta 1 which enhances the segregational stability of pAM beta 1-derived cloning vectors in Bacillus subtilis. Plasmid. 1991, 26 (3): 209-221. 10.1016/0147-619X(91)90044-W

Sambrook J, Russell DW, et al: Transformation of E. coli by Electroporation. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual Cold Spring Harbor. 1.119-111.122. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1991.

Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J: Requirements for transformation in Bacilus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961, 81 (5): 741-746.

Meyer F, Goesmann A, McHardy AC, Bartels D, Bekel T, Clausen J, Kalinowski J, Linke B, Rupp O, Giegerich R, et al: GenDB–an open source genome annotation system for prokaryote genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (8): 2187-2195. 10.1093/nar/gkg312

Richter M, Lombardot T, Kostadinov I, Kottmann R, Duhaime MB, Peplies J, Glockner FO: JCoast - a biologist-centric software tool for data mining and comparison of prokaryotic (meta)genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008, 9: 177- 10.1186/1471-2105-9-177

Krause M, Ukkonen K, Haataja T, Ruottinen M, Glumoff T, Neubauer A, Neubauer P, Vasala A: A novel fed-batch based cultivation method provides high cell-density and improves yield of soluble recombinant proteins in shaken cultures. Microb Cell Fact. 2010, 9: 11- 10.1186/1475-2859-9-11

Welsch N, Homuth G, Schweder T: Suitability of different beta-galactosidases as reporter enzymes in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012, 93 (1): 381-392. 10.1007/s00253-011-3645-0

le Hoi T, Voigt B, Jurgen B, Ehrenreich A, Gottschalk G, Evers S, Feesche J, Maurer KH, Hecker M, Schweder T: The phosphate-starvation response of Bacillus licheniformis. Proteomics. 2006, 6 (12): 3582-3601. 10.1002/pmic.200500842

Laemmli UK: Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970, 227 (5259): 680-685. 10.1038/227680a0

Candiano G, Bruschi M, Musante L, Santucci L, Ghiggeri GM, Carnemolla B, Orecchia P, Zardi L, Righetti PG: Blue silver: a very sensitive colloidal Coomassie G-250 staining for proteome analysis. Electrophoresis. 2004, 25 (9): 1327-1333. 10.1002/elps.200305844

Hochgrafe F, Wolf C, Fuchs S, Liebeke M, Lalk M, Engelmann S, Hecker M: Nitric oxide stress induces different responses but mediates comparable protein thiol protection in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190 (14): 4997-5008. 10.1128/JB.01846-07

, : R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2008, Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing

Wickham H: ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. 2009, New York: Springer

Rohn H, Junker A, Hartmann A, Grafahrend-Belau E, Treutler H, Klapperstuck M, Czauderna T, Klukas C, Schreiber F: VANTED v2: a framework for systems biology applications. BMC Syst Biol. 2012, 6 (1): 139- 10.1186/1752-0509-6-139

Markham NR, Zuker M: UNAFold: software for nucleic acid folding and hybridization. Methods Mol Biol. 2008, 453: 3-31. 10.1007/978-1-60327-429-6_1

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF reference 0315400A/B) in the frame of the BIOKATALYSE2021 network and the BACELL-SysMo project (reference 031397A). We thank Jana Matulla and Daniel Götze for their excellent technical support and Stephanie Markert for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JK has devised and carried out most of the experiments and written the manuscript. IP has transformed the B. subtilis ACE mutant and has carried out preliminary cultivations and RNA analyses. HM and ML have carried out the metabolomic investigation. DA has performed the MS-analysis and provided the MS-methodology description for the manuscript. AE has provided information about primer extension experiments of the aceBA operon. TS conducted the research, analyzed data and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabisch, J., Pratzka, I., Meyer, H. et al. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for growth on overflow metabolites. Microb Cell Fact 12, 72 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-12-72

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-12-72