Abstract

Background

Adiponectin acts as an antidiabetic, antiinflammatory and antiatherogenic adipokine. These effects are assumed to be mediated by the recently discovered adiponectin receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to determine whether variations in the AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 genes may contribute to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and inflammation.

Methods

We sequenced all seven coding exons of both genes in 20 unrelated German subjects with metabolic syndrome and tested genetic variants for association with glucose, lipid and inflammatory parameters.

Results

We identified three AdipoR2 variants (+795G/A, +870C/A and +963C/T) in perfect linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 1) with a minor allele frequency of 0.125. This haplotype was associated with higher plasma adiponectin levels and decreased fasting triglyceride, VLDL-triglyceride and VLDL-cholesterol levels. No association, however, was observed between the AdipoR2 SNP cluster and glucose metabolism.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify an association between genetic variants of the adiponectin receptor genes and plasma adiponectin levels. Furthermore, our data suggest that AdipoR2 may play an important role in triglyceride/VLDL metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adiponectin (also known as AdipoQ, APM1, and Acrp30) is a hormone secreted by adipocytes that acts as an antidiabetic [1–5], antiinflammatory [6, 7], and antiatherogenic [8–10] adipokine. Plasma adiponectin levels are significantly reduced in obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease [11–17]. Plasma adiponectin concentrations are inversely correlated with HOMA score, insulin levels, visceral and total adipose tissue mass, plasma triglycerides, total and LDL-cholesterol levels [18]. Conversely, adiponectin is directly correlated with VLDL apoB catabolism and HDL-cholesterol levels [18]. Molecularly, adiponectin was shown to increase insulin sensitivity by enhancing insulin's suppressive effect on glucogenesis [2, 3] and by increasing fatty acid oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle through activation of AMP kinase and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)-α [1, 5, 6]. Adiponectin's antiinflammatory and antiatherogenic effects are thought to be mediated by inhibition of TNF-α induced nuclear factor-κB activation [19], inhibition of expression of adhesion molecules [20], decreased smooth muscle cell proliferation [8], and reduced foam cell formation [21].

Recently, two related but distinct receptors for adiponectin were identified, termed adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1) and adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2) [22]. AdipoR1 was shown to be ubiquitously expressed, whereas AdipoR2 expression is more restricted to skeletal muscle and liver. In vitro overexpression and knockout experiments demonstrated the receptors' ability to ligand-dependently activate AMP kinase and PPAR-α, and to stimulate fatty acid oxidation and glucose uptake in murine hepatocytes and C2C12 myocytes [22]. Civitarese et al. [23] reported that non-diabetic Mexican- American subjects with a family history of type 2 diabetes exhibited significantly lower levels of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 mRNA in skeletal muscle compared with those without a family history. Expression levels of both receptors were positively correlated with insulin sensitivity [23].

Assuming that adiponectin receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 mediate the antidiabetic and antiinflammatory effects of adiponectin, we hypothesized that genetic variation in AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 may contribute to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation. We addressed this question by screening AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 for genetic variants and testing for an association between the observed sequence variation and glucose, lipid, and inflammatory parameters in overweight, non-diabetic, insulin resistant subjects.

Methods

Ascertainment of subjects

Twenty insulin resistant, abdominal overweight, unrelated German individuals were previously recruited for a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study to determine the effect of telmisartan, an angiontensin type-1 receptor blocker with PPAR-γ activating properties, on glucose and lipid metabolism as well as inflammatory parameters [24]. Insulin resistance was defined as HOMA index ≥ 2.3. Subjects with manifest diabetes mellitus or secondary reasons for insulin resistance (e.g. steroid therapy) were excluded. Abdominal overweight was defined as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and waist circumference of ≥ 95 cm in men or ≥ 80 cm in women, respectively. Only subjects with a minimum blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg were included. Subjects with a known history of atherosclerosis (cerebrovascular, peripheral arterial, or coronary) as well as subjects with severe hyperlipoproteinemia (defined as triglycerides >800 mg/dl or LDL-cholesterol >190 mg/dl) were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were a blood pressure of >160/95 mmHg, habitual alcohol consumption of >30 g/d, antihypertensive medication, statin or lipid lowering therapy, consuming illness, or a contraindication against the use of angiotensin II receptor blockers. Subjects were randomised to first receive placebo or telmisartan (40 mg/d) for 12 weeks, after which they received the other medication (telmisartan or placebo). At screening and at the end of each treatment phase primary and secondary parameters were determined. Participating subjects were asked not to change their dietary habits and physical activity throughout the study. The Ethics Committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich approved the study protocol and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Determination of glucose and lipid metabolism parameters

Glucose metabolism was evaluated by fasting plasma glucose (FPG), an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and an intravenous glucose tolerance test (iv GTT). Fasting values included glucose, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations. The OGTT was performed using 75 g glucose following a 12 h fast and was evaluated concerning the (incremental) area under the curve defined by glucose concentrations determined at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. To calculate the (incremental) area under the insulin curve during OGTT, insulin was also determined at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. The intravenous glucose tolerance test was performed using 25 g glucose. Both plasma glucose and insulin were measured at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 minutes after glucose bolus application. The (incremental) area under the curve for plasma glucose and for insulin was determined. First phase insulin secretion, second phase insulin secretion, insulin resistance index, and the composite index (Matsuda) were calculated based on the data derived from the OGTT as previously described [25].

Triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations were measured using a commercial kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Preparative ultracentrifugation was performed to isolate VLDL. Cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were determined in the supernatant and total cholesterol in the infranatant (containing LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol). After precipitation of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins, HDL-cholesterol was determined in the infranatant. LDL-cholesterol was calculated by subtraction of HDL-cholesterol from total cholesterol in the infranatant. Additionally, postprandial lipoprotein metabolism was evaluated using a standardized oral fat tolerance test. After fasting for 12 hours all subjects ingested a fatty meal, consisting of 100 ml milk (3.5% fat), 150 ml cream (30% fat), 70 ml corn oil, 90 g egg, 10 g sugar and 3.5 g coffee flavour. This standard meal yields 1305 kilocalories, 87% from fat, 7% from carbohydrates, and 6% from protein. Following the fat load, samples were taken every 2 h for 10 h. Total triglyerides and triglycerides in the d < 1.006 g/ml fraction (containing chylomicrons, chylomicron remnants and VLDL) were determined.

To elucidate possible effects on inflammatory processes, high-sensitive (hs-) C-reactive protein (CRP) (Dade Behring), interleukin-6 (IL-6) (R&D Systems), fibrinogen (Dade Behring), and adiponectin (R&D Systems) concentrations were determined.

Identification of adiponectin receptor variants

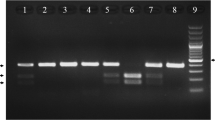

Genotyping was performed on above described 20 unrelated subjects. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for the seven coding exons of both adiponectin receptors were selected in intronic sequence at least 50 base pairs away from the intron/exon boundaries using VectorNTI (Invitrogen). Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using the QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit (Qiagen). PCR reactions containing 100 ng of DNA template were amplified in a final volume of 25 μL by denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles (95°C for 45 seconds, 55°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute), and an extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel, and, after confirmation of a single band with the expected size, were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). Purified fragments then underwent DNA cycle sequencing using ABI PRISM Big Dye terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems) and appropriate sequencing primers. Sequences were aligned using VectorNTI (Invitrogen) software, and electropherograms were viewed using Chromas Version 1.45 program. Allelic variations noted from multiple alignments were verified by inspecting the respective electropherograms.

Statistical analysis

Association of genetic variants with metabolic parameters was tested using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Results of the metabolic studies are depicted as median and interquartile range.

In silico searches were done at the web site of the National Center for Biotechnology Information's database SNP (dbSNP) [26] to determine if any polymorphic sites identified through our sequencing matched those already found.

Results

All seven coding exons of the AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 genes were sequenced in 20 abdominal overweight (BMI 31.0 (29.3–34.6) kg/m2, waist to hip ratio 0.88 (0.83–0.93)), insulin resistant (HOMA 3.35 (2.52–4.43)), unrelated German individuals previously recruited for a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study to determine the effect of telmisartan, an angiotensin type-1 receptor blocker with PPAR-γ activating properties, on glucose and lipid metabolism as well as inflammatory parameters [24]. DNA sequence analysis of the AdipoR1 gene revealed one genetic variation not yet reported in dbSNP (Table 1). In the AdipoR2 gene, sequencing identified seven variants with two of them previously reported in dbSNP (Table 1). Interestingly, three AdipoR2 variants (+795G/A (rs16928751), +870C/A (Ile290Ile) and +963C/T (rs9805042)) were in perfect linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 1) and showed a minor allele frequency of 0.125. Therefore, we decided to focus on this haplotype to study the impact of genetic variants of AdipoR2 on glucose, lipid, and inflammatory parameters in above described subjects.

Subjects with (AdipoR2-SNP) and without the AdipoR2 SNP cluster (AdipoR2) did not differ in age, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, parameters of glucose metabolism, inflammatory parameters, total cholesterol, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol concentrations (Tables 2,3). However, fasting triglycerides were consistently significantly lower in subjects with the AdipoR2 SNP cluster at three different time points (baseline, end of placebo treatment (Figure 1), end of telmisartan treatment) (Tables 2,3). Furthermore, the AdipoR2 SNP cluster showed a trend for association with reduced fasting VLDL-triglyceride and fasting VLDL-cholesterol levels (Table 3). No association was found between the AdipoR2 SNP cluster and parameters of postprandial triglyceride metabolism (Table 3). Interestingly, the AdipoR2 cluster was associated with significantly lower adiponectin levels (Table 3, Figure 2) at two different timepoints and showed a trend for association with lower adiponectin levels at one timepoint (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study was designed to test the hypothesis that genetic variation in the recently identified adiponectin receptor genes may contribute to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation. By sequencing all seven coding exons of the AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 genes in overweight, non-diabetic, insulin resistant subjects we identified a common AdipoR2 SNP cluster that was associated with 1) increased adiponectin levels and 2) decreased fasting triglyceride, VLDL-triglyceride and VLDL-cholesterol levels. Our study therefore suggests that AdipoR2 may play an important role in triglyceride/VLDL metabolism. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report an association between adiponectin receptor gene variants and plasma adiponectin levels.

Stefan et al. [27] recently reported the identification of seven variants of AdipoR2 including the three exonic variants +795G/A, +870C/A and +963C/T referred to as the AdipoR2 SNP cluster in the present study. By examining 502 German non-diabetic patients, Stefan et al. [27] showed these variants to be in high linkage disequilibrium (r2 ≥ 0.95) with a minor allele frequency of 0.12 consistent with the results of our study. In contrast to our results, however, Stefan et al. [27] did not find an association between these variants and adiponectin or triglyceride levels. This discrepancy may be attributed to different characteristics of the study populations. Subjects in the present study showed a markedly higher BMI (means: 31.8 versus 26.4 kg/m2) and insulin resistance index (HOMA (means): 3.78 versus 1.82), lower adiponectin levels (means: 2586 versus 10844 ng/ml) and, considering these differences, most likely higher lipid parameters (Stefan et al. [27] did not present actual lipid data in their manuscript).

Of course, small numbers of subjects can lead to erroneous results and conclusions. However, determination of metabolic parameters at three different timepoints (0, 12 and 24 weeks) yielded consistent and reproducible results, thus making random associations unlikely.

Adiponectin acts as an antidiabetic, antiinflammatory, and antiatherogenic adipokine. Civitarese et al. [23] reported that in non-diabetic Mexican Americans skeletal muscle specific expression levels of AdipoR2 but not AdipoR1 were positively correlated with plasma adiponectin concentrations. Consistent with these data, we demonstrate that genetic variants of AdipoR2 were associated with higher plasma adiponectin levels.

Furthermore, we show that these variants were associated with lower fasting triglyceride, VLDL-triglyceride and VLDL-cholesterol levels suggesting an important role of adiponectin receptor 2 in triglyceride/VLDL metabolism. Staiger et al. [28] demonstrated that AdipoR2 mRNA expression in human myotubes was only associated with plasma triglyceride levels, whereas AdipoR1 mRNA expression was positively correlated with in vivo insulin and C-peptide concentrations, first phase insulin secretion, plasma triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations. The lack of association between genetic variants of AdipoR2 and the triglyceride iAUC in our study suggests that AdipoR2 does not play a role in chylomicron secretion or hydrolysis. In contrast, association with fasting triglyceride, VLDL-triglyceride and VLDL-cholesterol concentrations would be consistent with a role of AdipoR2 in the metabolism of endogenous triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and possibly postprandial remnant lipoproteins. Ng et al. [18] previously reported that adiponectin was inversely associated with plasma triglyceride levels and directly correlated with VLDL apoB catabolism.

The underlying mechanism resulting in an association of the AdipoR2 SNP cluster with increased adiponectin levels and decreased triglyceride/VLDL concentrations still needs to be determined. We hypothesize that these genetic variants, all of them being silent mutations, are in linkage disequilibrium with another yet unidentified functional variation in the AdipoR2 gene.

Damcott et al. [29] recently reported that genetic variation in both adiponectin receptor genes was associated with type 2 diabetes. However, all these genetic variants were non-exonic variants and could therefore not be examined in the present study. Our data did not show any association between the AdipoR2 SNP cluster and glucose metabolism in overweight, non-diabetic, insulin resistant patients.

In conclusion, our data provide the first evidence for an association between variation in the AdipoR2 gene and plasma adiponectin concentrations as well as triglyceride and VLDL levels. Larger studies are necessary to confirm the results of this pilot study.

Abbreviations

- AdipoR1:

-

adiponectin receptor 1

- AdipoR2:

-

adiponectin receptor 2

- apoB:

-

apolipoprotein B

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- HbA1c:

-

hemoglobin A1c

- HDL:

-

high density lipoprotein

- HOMA:

-

homeostasis model assessment

- iAUC:

-

incremental area under the curve

- ivGTT:

-

intravenous glucose tolerance test

- LDL:

-

low density lipoprotein

- OGTT:

-

oral glucose tolerance test

- PPAR:

-

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

- dbSNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism database

- TNF:

-

tumor necrosis factor

- VLDL:

-

very low density lipoprotein

References

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Ezaki O, Akanuma Y, Gavrilova O, Vinson C, Reitman ML, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Yoda M, Nakano Y, Tobe K, Nagai R, Kimura S, Tomita M, Froguel P, Kadowaki T: The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001, 7: 941-946. 10.1038/90984.

Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE: The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2001, 7: 947-953. 10.1038/90992.

Combs TP, Berg AH, Obici S, Scherer PE, Rossetti L: Endogenous glucose production is inhibited by the adipose-derived protein Acrp30. J Clin Invest. 2001, 108: 1875-1881. 10.1172/JCI200114120.

Maeda N, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Nagaretani H, Furuyama N, Kondo H, Takahashi M, Arita Y, Komuro R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Tochino Y, Okutomi K, Horie M, Takeda S, Aoyama T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. Nat Med. 2002, 8: 731-737. 10.1038/nm724.

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, Eto K, Akanuma Y, Froguel P, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Carling D, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kahn BB, Kadowaki T: Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2002, 8: 1288-1295. 10.1038/nm788.

Xu A, Wang Y, Keshaw H, Xu LY, Lam KS, Cooper GJ: The fat-derived hormone adiponectin alleviates alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2003, 112: 91-100. 10.1172/JCI200317797.

Fernandez-Real JM, Lopez-Bermejo A, Casamitjana R, Ricart W: Novel interactions of adiponectin with the endocrine system and inflammatory parameters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88: 2714-2718. 10.1210/jc.2002-021583.

Matsuda M, Shimomura I, Sata M, Arita Y, Nishida M, Maeda N, Kumada M, Okamoto Y, Nagaretani H, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Komuro R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Nagai R, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis. The missing link of adipo-vascular axis. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277: 37487-37491. 10.1074/jbc.M206083200.

Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Nishida M, Arita Y, Kumada M, Ohashi K, Sakai N, Shimomura I, Kobayashi H, Terasaka N, Inaba T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002, 106: 2767-2770. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000042707.50032.19.

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Imai Y, Shimozawa N, Hioki K, Uchida S, Ito Y, Takakuwa K, Matsui J, Takata M, Eto K, Terauchi Y, Komeda K, Tsunoda M, Murakami K, Ohnishi Y, Naitoh T, Yamamura K, Ueyama Y, Froguel P, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kadowaki T: Globular adiponectin protected ob/ob mice from diabetes and ApoE-deficient mice from atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 2461-2468. 10.1074/jbc.M209033200.

Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, Hotta K, Shimomura I, Nakamura T, Miyaoka K, Kuriyama H, Nishida M, Yamashita S, Okubo K, Matsubara K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999, 257: 79-83. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255.

Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuda M, Okamoto Y, Iwahashi H, Kuriyama H, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Nishida M, Kihara S, Sakai N, Nakajima T, Hasegawa K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y: Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000, 20: 1595-1599.

Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, Tataranni PA: Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86: 1930-1935. 10.1210/jc.86.5.1930.

Kumada M, Kihara S, Sumitsuji S, Kawamoto T, Matsumoto S, Ouchi N, Arita Y, Okamoto Y, Shimomura I, Hiraoka H, Nakamura T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Osaka CAD Study Group: Coronary artery disease. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003, 23: 85-89. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000048856.22331.50.

Pischon T, Girman CJ, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Hu FB, Rimm EB: Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA. 2004, 291: 1730-1737. 10.1001/jama.291.14.1730.

Trujillo ME, Scherer PE: Adiponectin-journey from an adipocyte secretory protein to biomarker of the metabolic syndrome. J Intern Med. 2005, 257: 167-175. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01426.x.

Matsuzawa Y: Therapy Insight: adipocytokines in metabolic syndrome and related cardiovascular disease. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006, 3: 35-42. 10.1038/ncpcardio0380.

Ng TW, Watts GF, Farvid MS, Chan DC, Barrett PH: Adipocytokines and VLDL metabolism: independent regulatory effects of adiponectin, insulin resistance, and fat compartments on VLDL apolipoprotein B-100 kinetics?. Diabetes. 2005, 54: 795-802.

Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Okamoto Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Hotta K, Nishida M, Takahashi M, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived plasma protein, inhibits endothelial NF-kappaB signaling through a cAMP-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2000, 102: 1296-1301.

Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, Hotta K, Nishida M, Takahashi M, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. 1999, 100: 2473-2476.

Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Nishida M, Matsuyama A, Okamoto Y, Ishigami M, Kuriyama H, Kishida K, Nishizawa H, Hotta K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Yamashita S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001, 103: 1057-1063.

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, Tsuchida A, Yokomizo T, Kita S, Sugiyama T, Miyagishi M, Hara K, Tsunoda M, Murakami K, Ohteki T, Uchida S, Takekawa S, Waki H, Tsuno NH, Shibata Y, Terauchi Y, Froguel P, Tobe K, Koyasu S, Taira K, Kitamura T, Shimizu T, Nagai R, Kadowaki T: Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature. 2003, 423: 762-769. 10.1038/nature01705.

Civitarese AE, Jenkinson CP, Richardson D, Bajaj M, Cusi K, Kashyap S, Berria R, Belfort R, DeFronzo RA, Mandarino LJ, Ravussin E: Adiponectin receptors gene expression and insulin sensitivity in non-diabetic Mexican Americans with or without a family history of Type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004, 47: 816-820. 10.1007/s00125-004-1359-x.

Nagel JM, Tietz AB, Göke B, Parhofer KG: Telmisartan improves glucose metabolism in non-diabetic subjects with insulin resistance. Metabolism. 2006.

Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Jarvinen H, Van Haeften T, Renn W, Gerich J: Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23: 295-301.

National Center for Biotechnology Information's database SNP (dbSNP). [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/]

Stefan N, Machicao F, Staiger H, Machann J, Schick F, Tschritter O, Spieth C, Weigert C, Fritsche A, Stumvoll M, Haring HU: Polymorphisms in the gene encoding adiponectin receptor 1 are associated with insulin resistance and high liver fat. Diabetologia. 2005, 48: 2282-2291. 10.1007/s00125-005-1948-3.

Staiger H, Kaltenbach S, Staiger K, Stefan N, Fritsche A, Guirguis A, Peterfi C, Weisser M, Machicao F, Stumvoll M, Haring HU: Expression of adiponectin receptor mRNA in human skeletal muscle cells is related to in vivo parameters of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes. 2004, 53: 2195-2201.

Damcott CM, Ott SH, Pollin TI, Reinhart LJ, Wang J, O'connell JR, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR: Genetic variation in adiponectin receptor 1 and adiponectin receptor 2 is associated with type 2 diabetes in the Old Order Amish. Diabetes. 2005, 54: 2245-2250.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research grant "Förderprogramm für Forschung und Lehre" from the University of Munich (UCB). KGP was supported by a research grant from Bayer-Vital. We are indebted to Inge Biller-Friedmann and Kerstin Henze for expert technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

UCB, ML, EFB, ABT, JMN, BG and PL declare that they have no competing interests. KGP was supported by a research grant from Bayer-Vital.

Authors' contributions

UCB and KGP conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. EFB and PL performed the experiments in this study. ABT, JMN and BG recruited the study subjects and participated in the study design and interpretation of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Broedl, U.C., Lehrke, M., Fleischer-Brielmaier, E. et al. Genetic variants of adiponectin receptor 2 are associated with increased adiponectin levels and decreased triglyceride/VLDL levels in patients with metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol 5, 11 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-5-11

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-5-11