Abstract

Background

The contribution of glycemic variability to macrovascular complications remains unclear. We therefore investigated the association between glycemic variability and cervical and/or intracranial atherosclerosis in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study in 216 type 2 diabetic patients with a hemoglobin A1c of 8.3 ± 1.7% and a median diabetes duration of 9.0 years. The standard deviation of blood glucose values (SDBG) and the mean amplitude of glycemic excursion (MAGE) were calculated from continuous glucose monitoring system data for assessing glycemic variability while 24h mean blood glucose (MBG) was calculated for measuring overall blood glucose level. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) was used to detect cervical and/or intracranial plaque, and ultrasonography was used to quantify carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) as an index of subclinical atherosclerosis.

Results

One hundred and fifty-three patients (70.8%) presented with cervical and/or intracranial lesions on MRA among 216 patients in the study. Elder age, increased systolic blood pressure, increased MBG and elevated low density lipoprotein cholesterol were independent contributors to plaque formation. In patients without stenosis (n = 63), SDBG (r = 0.412, P = 0.001) and MAGE (r = 0.365, P = 0.005) were both correlated with carotid IMT and these relationships remained significant in multiple linear regression analysis (multiple R2 = 0.314 for the model including SDBG and multiple R2 = 0.268 for the model including MAGE). However, SDBG and MAGE were not significantly different among patients with different stenosis degrees.

Conclusions

Glycemic variability is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Macrovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease are major complications of type 2 diabetes. Previous studies have shown the association between averaged mean levels of glycemia and macrovascular complications [1, 2]. Meanwhile, several lines of evidence have raised the possibility that glycemic variability, which includes both upward and downward acute glucose changes, is another important component of dysglycemia [3]. Glycemic variability can have deleterious effects on the development and progression of macrovascular complication through oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [4, 5]. With the emergence of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology, the assessment of glycemic variability is now much less cumbersome. However, the exact role of glucose variability in the development of atherosclerosis remains unclear.

Atherosclerosis is a complex multifactorial disease, often preceding the development of diabetic macrovascular complications. Carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), measured noninvasively by ultrasonography, is accepted as an indicator of subclinical atherosclerosis, and has been reported to be directly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [6]. Furthermore, in terms of defining the presence of plaque, the technology of 3D time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (3D-TOF-MRA) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (CEMRA) are reported to be more informative than ultrasonography [7, 8]. To gain insight into the role of glycemic variability in the different stages of atherosclerosis, we used both ultrasonography and MRA to determine preclinical atherosclerosis and plaque formation. The aims of this study were: (i) to investigate the prevalence of atherosclerotic plaque by examining the cervical and intracranial arteries using MRA in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients; and (ii) to explore the role of glycemic variability in both the subclinical stage and plaque formation stage of atherosclerosis in this population.

Methods

Study populations

The study was carried out over a period of 12 months between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2008. We included 216 type 2 diabetic patients who consulted for complications screening at the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism in our hospital on an annual basis. Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed according to 1999 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [9]. Eligibility was based on a stable therapeutic regimen with oral hypoglycemic agents and/or insulin for the previous 3 months. Exclusion criteria included recent acute complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state, severe and recurrent hypoglycemic events in the previous 3 months, a history of hepatic or renal impairment, or of other diseases that can influence glucose metabolism, including recent acute cerebral stroke, acute myocardial infarction, malnutrition, and cancers. In addition, claustrophobic patients, and patients with valvular prostheses, vascular clips, cardiac pacemakers, or other implanted devices sensitive to strong magnetic fields, were also excluded from the study. The original study received approval from the Ethics Committees of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital in accordance with the principle of the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

CGM parameters

Subcutaneous interstitial glucose was monitored continuously for 3 consecutive days using a retrospective CGM system (Medtronic Inc, Northridge, CA, USA). The sensor of the CGM system was inserted on day 0 and removed after 72 h; this generated a daily record of 288 continuous sensor values. A minimum of four capillary blood glucose readings per day, as measured by a SureStep blood glucose meter (LifeScan, Milpitas, CA, USA), were entered into the CGM system for calibration. The 24h mean blood glucose (MBG) level was calculated from the 288 consecutive sensor readings over a 24h period. The 24h MBG and intraday glycemic variability were based on the mean values taken on days 1 and 2. Intraday glycemic variability parameters include the standard deviation of blood glucose values (SDBG) [10] and the mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE) [11]. MAGE was calculated by measuring the arithmetic mean of the differences between consecutive peaks and nadirs; measurement in the peak-to-nadir or nadir-to-peak direction was determined by the first qualifying excursion; only excursions of more than 1 SD of the mean glycemic values were considered because MAGE was designed to quantify only major swings of glycemia instead of minor ones. All patients wore blinded CGM system and received the same therapy as before admission. The CGM monitoring was performed in the hospital and the mean CGM period ± SD was 71 ± 3h. The reference values for CGM system in Chinese population have been reported elsewhere [12, 13].

Patients were instructed to adhere to a standard diet during the three-day period of CGM sensor monitoring. The diet was designed to ensure a total daily caloric intake of 25 kcal/kg/day, with 55% of calories coming from carbohydrates, 17% from proteins, and 28% from fats. Written instructions were provided to achieve the appropriate caloric content and to guide the consumption times, which included breakfast (20% of daily calories, 06:30–07:30), lunch (40%, 11:30–12:30), and dinner (40%, 18:00–19:00).

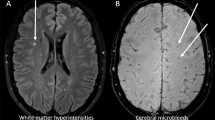

Cervical and intracranial magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) examination

All MRA examinations were performed using a 3.0 tesla MR system (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems). Intracranial MRA was performed using a 3D-TOF-MRA sequence with an 8-channel head coil or a 16-channel craniocervical joint coil. The 3D-TOF-MRA was obtained with repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) 30/3.2 msec, flip angle 20°, field of view (FOV) 250 × 220 mm, four slabs (180 slices), 1.2 mm slice thickness, matrix 1024 × 1024 and an acquisition time of 8 min 56 s. The acquired images were then transferred to a separate workstation (View Forum; Philips Medical Systems) to obtain both the maximum-intensity projection (MIP) and volume rendering (VR) images. Cervical MRA was performed using the high spatial resolution CEMRA sequence with a 16-channel craniocervical joint coil. Parameters were as follows: a 4.7/1.79 msec TR/TE; 27° flip angle; 320 × 320 mm FOV; 150 slices; 1.0 mm slice thickness, matrix 704 × 704 and an acquisition time of 1 min 27 s. A 1 ml bolus dose of gadolinium (0.5 mol/l, Magnevist; Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals) was administered intravenously at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/s by a power injector, followed by 21 ml of saline flush to measure the time taken for the gadolinium to reach the aortic arch. Subsequently, 19 ml of gadolinium was injected at the same rate. The average scanning delay time was 13 s (11–19 s).

The intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery (I-ICA), the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries (ACA, MCA and PCA), the intracranial vertebral artery (I-VA), and the basilar artery (BA) were evaluated by intracranial MRA. The common carotid artery (CCA), the extracranial portion of the internal carotid artery (E-ICA), the extracranial vertebral artery (E-VA), the external carotid artery (ECA), and the subclavian artery (SUB) were evaluated by cervical MRA. All MRA findings were reviewed by two investigators who were blind to patient clinical data. The severity of arterial stenosis was rated into five grades depending on the narrowing of the arteries: without any reduction of arterial diameter; <10% reduction of arterial diameter; 10–50% reduction; 51–99% reduction; and complete occlusion [14]. If stenosis severity for a given artery was different between the right and left sides, the side with more severe stenosis was used for grade assignment and analysis. When two or more stenoses were detected in different arteries, the most severe arterial stenosis grade was used for patient classification.

Ultrasound measurement

Common carotid arteries were assessed using a high resolution B-mode ultrasound (Sequoia 512, Siemens, Germany) equipped with a 10 MHz probe, as previously described [15]. A single sonographer blind to patient clinical characteristics measured bilateral carotid arteries. Both common carotid arteries were scanned from proximal to distal in relation to the bifurcation. IMT was measured at the far wall of both common carotid arteries, approximately 1 cm proximal to the carotid bulb. The carotid IMT value was calculated as the mean of the maximal IMT of each carotid artery.

Anthropometric and biochemical measurements

Each patient had a physical examination including measurements of height, weight, and blood pressure in an air-conditioned, quiet room. We calculated body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg) divided by squared height (m). The blood pressure was measured indirectly using a mercury sphygmomanometer. Sitting blood pressure was measured after 5-min rest with a blood pressure cuff appropriately sized to arm circumference and placed on the subject’s non-dominant arm. The average of three measurements at two minute intervals was used for the analysis. Smoking status was based on an interview. Subjects were classified as nonsmokers or current smokers.

On a separate day from 3-day CGM measurement, venous blood sample was drawn on 6 AM after a 10 hour overnight fasting to test the biochemical measurements. Hepatic biomarkers, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST); renal function biomarkers including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), plasma creatinine, and uric acid; triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), were determined by standard enzymatic methods using a biochemical analyzer (Hitachi 7600–020, Tokyo, Japan). Fasting plasma glucose levels were assayed by the glucose oxidase method. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography with a Variant II Hemoglobin A1c analyzer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± SD, whereas skewed variables are presented as median (interquartile range: 25th to 75th percentile). Clinical characteristics that followed a normal distribution were compared among groups using one-way analysis of variance with post-hoc LSD test, while those with non-normal distribution were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. In addition, a chi-squared test was used to determine the differences between groups in categorical variables. Variables that did not follow a normal distribution were log-transformed. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent factors for cervical and/or intracranial plaque formation. The results of the regression were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). In patients with negative finding on MRA, Spearman correlation coefficients were employed for correlation analysis between carotid IMT and variables. Multiple regression models were used to explore the influence of different variables on carotid IMT and to adjust for covariates. We calculated the number of patients required for the study to reject the null hypothesis 90% of the time (i.e., with a 1-tailed type II error rate of 0.1) when r was 0.40 or higher with a 2-tailed type I error at the 0.05 level of significance. Because this calculation led to a sample size of at least 61, the number 63 of patients who had negative finding on MRA was sufficient. A P value of <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

Subjects had a mean ± SD age of 63 ± 10 years (range: 40–86 years), mean HbA1c levels of 8.3 ± 1.7 %, and a median (interquartile range) diabetes duration of 9.0 (5.0–13.3) years. Patients were classified according to the presence and severity of arterial stenosis: patients without stenosis (n = 63); <10% stenosis group: patients with less than 10% stenosis in the most severely stenotic artery (n = 105); 10–50% stenosis group: patients with 10–50% stenosis in the most severely stenotic artery (n = 40); 51–99% stenosis group: patients with 51–99% stenosis in the most severely stenotic artery (n = 8); no patient had complete occlusion on MRA. The baseline characteristics and laboratory data are shown in Table 1. 10-50% stenosis group and 51-99% stenosis group were combined as one group (10-99% stenosis group) listed in Table 1 because there were only 8 patients in the 51-99% stenosis group. Compared to patients without stenosis, patients in <10% stenosis group and 10-99% group were older and had significant higher TC levels. Also, patients in 10-99% stenosis group had significantly higher systolic blood pressure, MBG and LDL-C levels than the other two groups (all P < 0.05). However, SDBG and MAGE were not statistically different among the three groups (both P > 0.05).

MRA findings

MRA findings are summarized in Table 2. Of all subjects, 153 (70.8%) patients presented with at least one cervical and/or intracranial atherosclerotic lesion. The intracranial atherosclerotic lesions were localized mainly at PCA, I-ICA, ACA, MCA and the cervical atherosclerotic lesions were localized mainly at CCA.

Logistic regression analysis of the different risk factors for cervical and intracranial atherosclerosis

Of potential confounding risk factors, multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that age (OR 1.115; 95.0% CI 1.065–1.168), systolic blood pressure (OR 1.030; 95.0% CI 1.005–1.056), MBG (OR 1.245; 95.0% CI 1.000–1.549) and LDL-C (OR 1.633; 95.0% CI 0.971–2.746) were independent factors for the presence of cervical and/or intracranial lesions. The independent variables included age, sex, BMI, smoking status, diabetes duration, HbA1c, MBG, MAGE, SDBG, blood pressure, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, ALT, AST, diabetes treatment, dyslipidemia treatment, antihypertensive treatment and aspirin use.

Association between carotid IMT and glycemic variability

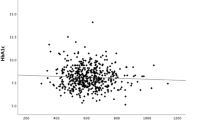

Patients were classified into 2 groups according to MRA results: subjects without plaque (n = 63) and subjects with plaque (n = 153). In the former group, when carotid IMT was tested for simple linear correlations against markers of glucose control and nonglycemic clinical and laboratory variables, statistically significant correlations were found with age (r = 0.497, P < 0.001), MAGE (r = 0.365, P = 0.005) and SDBG (r = 0.412, P = 0.001) (Figure 1). In contrast, in subjects with atherosclerotic plaque (n = 153), carotid IMT only correlated with age (r = 0.173, P = 0.038) among all the markers of glycemic and nonglycemic variables and no correlation was observed with MAGE (r = 0.089, P = 0.298) and SDBG (r = 0.122, P = 0.147).

Correlation between carotid IMT and glycemic variability in subjects without atherosclerotic lesion on MRA. (A) The standard deviation of blood glucose (SDBG) was positively correlated to carotid IMT (r = 0.412, P = 0.001) (n = 63). (B) The mean amplitude of glycemic excursion (MAGE) was positively correlated to carotid IMT (r = 0.365, P = 0.005) (n = 63)

Next, multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess the independent effects of glycemic and nonglycemic variables on carotid IMT in patients without plaque (n = 63) (Table 3). The independent variables included age, diabetes duration, blood pressure, HbA1c, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, MBG, SDBG and MAGE. Because a strong intercorrelation was observed between MAGE and SDBG (r = 0.813; ie, R2 =0.63) in the univariate analysis, 2 independent models were tested, 1 including the SDBG (model 1) and 1 the MAGE (model 2). Both SDBG (standardized β = 0.335, P = 0.005) and MAGE (standardized β = 0.319, P = 0.010) remained significant in stepwise regression analysis (multiple R2 = 0.314 for the model including SDBG and multiple R2 = 0.268 for the model including MAGE). The regression equations are as follows: Model 1: Carotid IMT (mm) = 0.270 mm + (0.007 mm * Age) + (0.065 mm *SDBG). Model 2: Carotid IMT (mm) = 0.272 mm + (0.007 mm * Age) + (0.023 mm * MAGE).

Discussion

The present study revealed a high prevalence of cervical and/or intracranial atherosclerotic lesions among type 2 diabetic patients as evaluated by MRA. More importantly, our study suggested that glycemic variability was associated with subclinical atherosclerosis before plaque formation because (1) SDBG and MAGE correlated with carotid IMT only in patients without atherosclerotic plaque; (2) conventional risk factors including elder age, hypertension, increased MBG and increased LDL-C were independent predictors of plaque formation; and (3) SDBG and MAGE were not significantly different among groups with different degrees of arterial stenosis.

Studies on glycemic variability

Chronic hyperglycemia and glycemic variability are two major glucose characteristics of diabetes. The relationships between chronic hyperglycemia and chronic complications have been well-studied [16]. By contrast, the measure of glucose variability introduces the possibility that multiple fluctuations of blood glucose could be more dangerous than either chronic stable hyperglycemia or a simple episode of acute hyperglycemia. Compared to chronic hyperglycemia, glycemic variability is poorly understood, mainly due to limitations of glucose monitoring techniques. However, the emergence of CGM system has made it possible to record the complete picture of 24 h glucose excursions, and thus the glycemic variability can be accurately and conveniently calculated. Studies on glycemic variability have shown its association with postprandial ß-cell dysfunction [17] and glycemic variability is becoming an important parameter when evaluating the efficacy of different hypoglycemic treatments [18]. Moreover, glycemic variability is also strongly correlated to HbA1c level in elderly male patients with type 2 diabetes [19], albeit glycemic variability does not provide additional prognostic value above and beyond already recognized risk factors for mortality during acute myocardial infarction [20]. On the contrary, the association between intraday glycemic variability and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes has been studied by Su et al. [21]. So far, the relationship between glycemic variability and diabetic macrovascluar complications remains unclear.

Atherosclerosis detection: MRA and ultrasonography

Until now, few studies have addressed the association between glycemic variability and atherosclerosis. Chen et al. [22] studied 36 patients with type 2 diabetes and demonstrated that carotid IMT was correlated with MAGE. However, the authors used ultrasound to detect both preclinical atherosclerosis and the plaque formation. As a quantitative variable, carotid IMT is a feasible technique for evaluating subclinical atherosclerosis but may have several limitations when defining plaque, including inability to visualize intracranial vessels, difficulties in detecting near-total occlusion, and high reliance on operator skill [23, 24]. For the Chinese population, assessing intracranial vessels is particularly important because East Asians were reported to be significantly more susceptible to intracranial atherosclerotic lesions than are Caucasians [25]. Thus, using ultrasound assessment alone, patients with only intracranial plaque cannot be accurately detected. Therefore, in terms of defining the presence of plaque, we evaluated both cervical and intracranial vessels using CEMRA and 3D-TOF-MRA. CEMRA is more specific and can provide additional diagnostic information than ultrasonography, while avoiding the potential complications of conventional angiography in assessing cervical vessels [7]. 3D-TOF-MRA allows more accurate evaluation of intracranial steno-occlusive disease among the noninvasive imaging techniques [8]. In addition, MRA technology depends less on the operator and is associated with lower inter-observer variability than is ultrasonography. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to use both MRA and ultrasonography to evaluate different stages of atherosclerosis in order to explore a potential relationship with glycemic variability.

Glucose fluctuation and atherosclerosis

Using the CGM system we report that, in diabetic patients without atherosclerotic lesions, SDBG and MAGE were significantly related to carotid IMT, raising the intriguing possibility that glycemic variability plays a key role in the subclinical stage of atherosclerosis. Our results are partly in agreement with several in vitro and epidemiological studies suggesting that glucose fluctuation can harm the arterial wall through oxidative stress and/or endothelial dysfunction [4, 5]. Meanwhile, as a major contributor to glycemic variability, postprandial blood glucose, especially the acute hyperglycemia after a meal or glucose load, was found to be strongly associated with endothelial function, carotid IMT and cardiovascular diseases [26, 27]. Suzuki et al. [28] found the attenuation of brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) in the postprandial state was correlated with postprandial glucose fluctuation and the postprandial serum insulin level in individuals with normal glucose tolerance. Esposito, et al. [29] found that incremental glucose peak, the maximal incremental increase in blood glucose obtained at any point after the meal, was correlated with carotid IMT, suggesting postprandial glucose is involved in the process of subclinical atherosclerosis. In addition, the management of postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes is related to regression of atherosclerosis [30]. For example, Mitiglinide, a short-acting insulinotropic agent to ameliorate postprandial hyperglycemia, was shown to reduce excess oxidative stress and inflammation [31].

Hypothesis

We speculate that endothelial dysfunction may underlie the association between glycemic variability and subclinical atherosclerosis. Although atherosclerosis is commonly described as the presence of plaque obstructing the lumen of the conduit arteries, endothelial dysfunction is regarded as the initial step in the development of atherosclerosis and can be observed preceding structural atherosclerotic changes in the vascular wall or ultrasonic evidence of plaque [32, 33]. Hashimoto et al. [34] studied the correlation between carotid IMT and FMD of the brachial artery, and found that FMD was related to carotid IMT only in subjects without overt atherosclerosis, which suggested that endothelial dysfunction correlates with carotid IMT before the development of macroscopic anatomic atherosclerosis. Therefore, because glycemic variability was reported to be associated with endothelial dysfunction [5], and endothelial dysfunction, the initial process of atherosclerosis, seems to be correlated with carotid IMT in subjects without overt plaque, we speculate that the association between larger glycemic variability and increased carotid IMT is most likely due to the mechanism of endothelial dysfunction. Unfortunately, we did not measure any marker to substantiate our assumption in this study. Further studies need to be carried out to elucidate the mechanism.

Clinical significance

Our study revealed that glycemic variability is related to subclinical atherosclerosis before the plaque is formed. On the other hand, we identified conventional risk factors such as age, hypertension, dyslipidemia and increased mean blood glucose level as important independent predictive factors for atherosclerotic plaque formation instead of glycemic variability. Indeed, substantial evidence suggests that chronic hyperglycemia plays a specific role in atherosclerosis progression in patients with diabetes [35]. Needless to say, the combination of antihyperglycemic treatment with lipid-lowering, antihypertensive, and antiplatelet therapy is currently regarded as the primary strategy for reducing the burden of macrovascular complications in diabetes [36–38].

In light of these results, we highlight the importance of adopting a multifactorial approach to the prevention of macrovascular disease in type 2 diabetic patients. Identifying patients at risk for atherosclerotic lesions using MRA technique may be a priority. In patients with lesions, strict blood-pressure control, lipid-lowering therapy should be emphasized. For those who have negative finding by MRA, early initiation of glycemic variability management is likely to be beneficial in preventing the development and progression of atherosclerosis.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, even though all the included patients received stable therapeutic regimen for 3 months before the study, a 2-day CGM profile may not sufficiently reflect the actual glycemic condition over a longer period. Second, because this was a cross-sectional study, our conclusions are based essentially only on correlation analysis. A larger prospective investigation is required in order to further demonstrate the role that glycemic variability plays in the process of atherosclerosis. Third, we did not assess the relationship between endothelial dysfunction and glycemic variability in the study to substantiate our results. Further studies are needed in the future.

Conclusions

In conclusion, glycemic variability is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetic patients. Further studies will be necessary to clarify the role of glucose variability as a potential contributory factor to the complex processes of atherosclerosis development.

Abbreviations

- CGM:

-

Continuous glucose monitoring

- IMT:

-

Intima-media thickness

- 3D-TOF-MRA:

-

3D time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography

- CEMRA:

-

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography

- MBG:

-

Mean blood glucose

- SDBG:

-

Standard deviation of blood glucose

- MAGE:

-

Mean amplitude of glycemic excursions

- I-ICA:

-

Intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery

- ACA:

-

Anterior cerebral artery

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

- PCA:

-

Posterior cerebral artery

- I-VA:

-

Intracranial vertebral artery

- BA:

-

Basilar artery

- CCA:

-

Common carotid artery

- E-ICA:

-

Extracranial portion of the internal carotid artery

- E-VA:

-

Extracranial vertebral artery

- ECA:

-

External carotid artery

- SUB:

-

Subclavian artery

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- FMD:

-

Flow-mediated dilation.

References

Selvin E, Marinopoulos S, Berkenblit G, Rami T, Brancati FL, Powe NR, Golden SH: Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004, 141: 421-431.

Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA: 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359: 1577-1589.

Monnier L, Colette C, Owens DR: Glycemic variability: the third component of the dysglycemia in diabetes. Is it important? How to measure it. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008, 2: 1094-1100.

Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, Michel F, Villon L, Cristol JP, Colette C: Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2006, 295: 1681-1687.

Ceriello A, Esposito K, Piconi L, Ihnat MA, Thorpe JE, Testa R, Boemi M, Giugliano D: Oscillating glucose is more deleterious to endothelial function and oxidative stress than mean glucose in normal and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2008, 57: 1349-1354.

O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK, Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group: Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 14-22.

Phan T, Huston J, Bernstein MA, Riederer SJ, Brown RD: Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of the cervical vessels: experience with 422 patients. Stroke. 2001, 32: 2282-2286.

Heiserman JE, Drayer BP, Keller PJ, Fram EK: Intracranial vascular stenosis and occlusion: evaluation with three-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography. Radiology. 1992, 185: 667-673.

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ: Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998, 15: 539-553.

Service FJ, O’Brien PC, Rizza RA: Measurements of glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1987, 10: 225-237.

Service FJ, Molnar GD, Rosevear JW, Ackerman E, Gatewood LC, Taylor WF: Mean amplitude of glycemic excursions, a measure of diabetic instability. Diabetes. 1970, 19: 644-655.

Zhou J, Li H, Ran X, Yang W, Li Q, Peng Y, Li Y, Gao X, Luan X, Wang W, Jia W: Reference values for continuous glucose monitoring in Chinese subjects. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32: 1188-1193.

Zhou J, Li H, Ran X, Yang W, Li Q, Peng Y, Li Y, Gao X, Luan X, Wang W, Jia W: Establishment of normal reference ranges for glycemic variability in Chinese subjects using continuous glucose monitoring. Med Sci Monit. 2011, 17: CR9-CR13.

Nael K, Villablanca JP, Pope WB, McNamara TO, Laub G, Finn JP: Supraaortic arteries: contrast-enhanced MR angiography at 3.0 T–highly accelerated parallel acquisition for improved spatial resolution over an extended field of view. Radiology. 2007, 242: 600-609.

Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, Oreste P, Paoletti R: Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation. 1986, 74: 1399-1406.

Stettler C, Allemann S, Juni P, Cull CA, Holman RR, Egger M, Krahenbuhl S, Diem P: Glycemic control and macrovascular disease in types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2006, 152: 27-38.

Kohnert KD, Augstein P, Zander E, Heinke P, Peterson K, Freyse EJ, Hovorka R, Salzsieder E: Glycemic variability correlates strongly with postprandial beta-cell dysfunction in a segment of type 2 diabetic patients using oral hypoglycemic agents. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32: 1058-1062.

Bao YQ, Zhou J, Zhou M, Cheng YJ, Lu W, Pan XP, Tang JL, Lu HJ, Jia WP: Glipizide controlled-release tablets, with or without acarbose, improve glycaemic variability in newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010, 37: 564-568.

Fang FS, Li ZB, Li CL, Tian H, Li J, Cheng XL: Influence of glycemic variability on the HbA1c level in elderly male patients with type 2 diabetes. Intern Med. 2012, 51: 3109-3113.

Lipska KJ, Venkitachalam L, Gosch K, Kovatchev B, Van den Berghe G, Meyfroidt G, Jones PG, Inzucchi SE, Spertus JA, DeVries JH, Kosiborod M: Glucose variability and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012, 5: 550-557.

Su G, Mi S, Tao H, Li Z, Yang H, Zheng H, Zhou Y, Ma C: Association of glycemic variability and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011, 10: 19.

Chen XM, Zhang Y, Shen XP, Huang Q, Ma H, Huang YL, Zhang WQ, Wu HJ: Correlation between glucose fluctuations and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010, 90: 95-99.

Mittl RL, Broderick M, Carpenter JP, Goldberg HI, Listerud J, Mishkin MM, Berkowitz HD, Atlas SW: Blinded-reader comparison of magnetic resonance angiography and duplex ultrasonography for carotid artery bifurcation stenosis. Stroke. 1994, 25: 4-10.

Bornstein NM, Beloev ZG, Norris JW: The limitations of diagnosis of carotid occlusion by Doppler ultrasound. Ann Surg. 1988, 207: 315-317.

Nishimaru K, McHenry LC, Toole JF: Cerebral angiographic and clinical differences in carotid system transient ischemic attacks between American Caucasian and Japanese patients. Stroke. 1984, 15: 56-59.

Temelkova-Kurktschiev TS, Koehler C, Henkel E, Leonhardt W, Fuecker K, Hanefeld M: Postchallenge plasma glucose and glycemic spikes are more strongly associated with atherosclerosis than fasting glucose or HbA1c level. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23: 1830-1834.

Bonora E, Muggeo M: Postprandial blood glucose as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in Type II diabetes: the epidemiological evidence. Diabetologia. 2001, 44: 2107-2114.

Suzuki K, Watanabe K, Futami-Suda S, Yano H, Motoyama M, Matsumura N, Igari Y, Suzuki T, Nakano H, Oba K: The effects of postprandial glucose and insulin levels on postprandial endothelial function in subjects with normal glucose tolerance. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012, 11: 98.

Esposito K, Ciotola M, Carleo D, Schisano B, Sardelli L, Di TD, Misso L, Saccomanno F, Ceriello A, Giugliano D: Post-meal glucose peaks at home associate with carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008, 93: 1345-1350.

Esposito K, Giugliano D, Nappo F, Marfella R: Regression of carotid atherosclerosis by control of postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2004, 110: 214-219.

Kitasato L, Tojo T, Hatakeyama Y, Kameda R, Hashikata T, Yamaoka-Tojo M: Postprandial hyperglycemia and endothelial function in type 2 diabetes: focus on mitiglinide. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012, 11: 79.

Luscher TF, Barton M: Biology of the endothelium. Clin Cardiol. 1997, 20 (11 Suppl 2): II-3-II-10.

Ross R: The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993, 362: 801-809.

Hashimoto M, Eto M, Akishita M, Kozaki K, Ako J, Iijima K, Kim S, Toba K, Yoshizumi M, Ouchi Y: Correlation between flow-mediated vasodilatation of the brachial artery and intima-media thickness in the carotid artery in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999, 19: 2795-2800.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group: The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993, 329: 977-986.

Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, Thomason MJ, Mackness MI, Charlton-Menys V, Fuller JH: Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004, 364: 685-696.

Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, Clark NG, Costa F, Eckel R, Fonseca V, Gerstein HC, Grundy S, Nesto RW, Pignone MP, Plutzky J, Porte D, Redberg R, Stitzel KF, Stone NJ: Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation. 2007, 115: 114-126.

Seaquist ER, Miller ME, Bonds DE, Feinglos M, Goff DC, Peterson K, Senior P: The impact of frequent and unrecognized hypoglycemia on mortality in the ACCORD study. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35: 409-414.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the involved clinicians, nurses, and technicians for their dedication to the study. This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81100590), the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (12QA1402500), the Shanghai United Developing Technology Project of Municipal Hospitals (SHDC12010115), and Shanghai Medical Program for Outstanding Young Talent (XYQ2011013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YM, JZ, ML and WJ conceived and designed the study. XM, DL, WL and CH recruited samples, ML and ML reviewed all the MRA results, YM, JZ and ML wrote the first draft of the paper. YW and YB critically reviewed the paper and contributed to discussion, and all authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and have approved the final version.

Yifei Mo, Jian Zhou, Mei Li contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, Y., Zhou, J., Li, M. et al. Glycemic variability is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 12, 15 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-12-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-12-15