Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes and therefore managing cardiovascular (CV) risk is a critical component of diabetes care. As incretin-based therapies are effective recent additions to the glucose-lowering treatment armamentarium for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), understanding their CV safety profiles is of great importance. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have been associated with beneficial effects on CV risk factors, including weight, blood pressure and lipid profiles. Encouragingly, mechanistic studies in preclinical models and in patients with acute coronary syndrome suggest a potential cardioprotective effect of native GLP-1 or GLP-1 receptor agonists following ischaemia. Moreover, meta-analyses of phase 3 development programme data indicate no increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) with incretin-based therapies. Large randomized controlled trials designed to evaluate long-term CV outcomes with incretin-based therapies in individuals with T2D are now in progress, with the first two reporting as this article went to press.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes, and is responsible for half of all deaths of these individuals [1]. Although there are trends toward a fall in this excess mortality risk (perhaps due to earlier detection of type 2 diabetes (T2D) coupled with improvements in care), people with T2D have an elevated risk of CVD compared with those without T2D and a poorer prognosis following an adverse CV event [2, 3]. The excess CV risk associated with T2D may arise from a complex interplay of several factors, including chronic hyperglycaemia, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and obesity [4].

Management of CVD risk factors is therefore of vital importance in T2D care. Improving glycaemic control has provided only limited success in reducing the macrovascular complications associated with T2D [5, 6], and so focus has inexorably shifted towards other CV risk factors (including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and obesity) that contribute to CV morbidity and mortality. More recently, the prevailing assumption that glucose-lowering is inextricably linked with outcome benefit has been challenged [7, 8] with the suspension of the European marketing authorisation for rosiglitazone in 2010, and restriction of its use in the U.S., following concerns of an increased risk of CV disorders, including myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure [9], and stroke [10].

Determining the optimal therapy regimen for individuals with T2D therefore requires careful consideration, and evidence regarding long-term CV safety of glucose-lowering therapies is required to inform better clinical decision-making. In 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) responded to this need by issuing guidelines that mandate a thorough assessment of CV risk in glucose-lowering drug development programmes [11]. The incretin-based therapies are the first drug classes to emerge within this environment of heightened regulatory attention. Clinical studies of incretin-based therapies have demonstrated improved glycaemic control with a low risk of hypoglycaemia and no weight gain, or in the case of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, weight loss [12, 13]. These effects, alongside others (summarised in Figure 1) are attractive therapeutic properties in the management of T2D, and signal potential CV benefit. Long-term CV outcomes trials are currently underway for many of the incretin-based therapies (Table 1) [14–24]. This review provides background information on the endogenous incretin system and incretin-based therapies, and examines the available data regarding the effects on CV risk markers and CV safety with incretin-based therapies.

Evidence acquisition

A literature search of established sources, including congress abstracts, was performed to identify recent publications dealing with the topic for review. Relevant articles were selected for review and discussion in light of the author’s knowledge of the field and clinical judgement. The European label for lixisenatide [25] was consulted for additional information. The official clinical trials registry at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov was also searched to identify long-term CV outcomes clinical trials with incretin-based therapies in individuals with T2D.

The incretin system and incretin-based therapies

Following nutrient intake, two major incretin hormones, GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), are secreted from the gastrointestinal tract into the circulation [26]. It is now recognised that GLP-1 and GIP are responsible for 50–70% of total insulin secretion after oral glucose intake in healthy individuals [26], augmenting insulin release in a glucose-dependent manner, and leading to reductions in average blood glucose levels. GLP-1 exerts an additional glucose-lowering effect through actions at pancreatic alpha cells which result in an inhibition of glucagon secretion [26]. There is evidence to suggest that the incretin system is functionally impaired in people with T2D, although this is not universally observed [27–31]. This impairment may contribute to the characteristic postprandial hyperglycaemia observed in affected individuals [27]. Native GLP-1 has been shown to reduce hyperglycaemia in T2D; however, as GLP-1 is rapidly (within 2–3 minutes) degraded by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), continuous GLP-1 infusion would be required to maintain optimal glycaemic control [32]. Therefore, incretin-based therapies have been developed either to raise endogenous levels of incretin hormones (DPP-4 agonists) or to mimic GLP-1 effects (GLP-1 receptor agonists) over more extended timeframes.

Pharmacological inhibition of the DPP-4 enzyme with DPP-4 inhibitors increases plasma incretin hormone levels. Several different oral DPP-4 inhibitors are clinically available, including sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin, vildagliptin (in the EU and Australia), teneligliptin and analagliptin (both available only in Japan) and gemigliptin (available only in Korea). Subcutaneous injection of GLP-1 receptor agonists mimics the effects of native GLP-1 through stimulation of the Gs-protein coupled GLP-1 receptor. Two GLP-1 receptor agonists are currently widely available: liraglutide (a GLP-1 analogue with 97% homology to native human GLP-1) and exenatide (53% homology to native human GLP-1). Exenatide was introduced to the market in 2007, having been developed from the peptide exendin-4 in the venom of the Gila monster, and is administered twice daily (BID). A major advantage of liraglutide when introduced in 2009 was its once daily administration. An extended release once-weekly formulation of exenatide (also known as exenatide long-acting release [LAR]) is also available in both the European Union [33] and in the U.S. [34]. Lixisenatide, a novel GLP-1 receptor agonist, was recently launched in several regions, including the European Union [25], and a number of GLP-1 receptor agonists are currently in clinical development, including albiglutide.

Cardiovascular effects of native GLP-1

The effects of native GLP-1 on contractility, heart rate and/or blood pressure have been investigated [35–37], but are not well-established. Differing effects of native GLP-1 on these parameters have been observed, presenting a complex picture. These varying effects may arise from differences in species, GLP-1 concentrations and experimental methods used.

Native GLP-1 exerts its effects via the GLP-1 receptor; but may also have GLP-1 receptor-independent effects [38]. The GLP-1 receptor is ubiquitously expressed, located not only in pancreatic cells but also in the lungs, kidneys, intestines, and peripheral and central nervous systems reviewed in [26, 37]. In addition, GLP-1 receptors are expressed in the CV system. In mice, GLP-1 receptors are distributed in myocardial tissue (left and right ventricles, septum and, to a lesser extent, atria), endocardium, microvascular endothelium, and coronary smooth muscle cells [38]. GLP-1 receptor expression in the human heart, including the coronary artery endothelial cells, has also been demonstrated [39, 40].

Data from animal models and pilot clinical studies have indicated that native GLP-1 may have cardioprotective effects in the setting of ischaemia, or following ischaemic injury [37, 38, 41, 42]. For example, in a study of 21 individuals with acute MI and severe systolic dysfunction after successful primary angioplasty, GLP-1 infusion (in addition to standard care) significantly improved left ventricular function compared with control individuals receiving standard care (including aspirin, clopidogrel, heparin, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and/or statins) [41]. Moreover, studies using the technique of brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation (measured by ultrasonography) during GLP-1 infusion in people with T2D and stable coronary artery disease suggest that GLP-1 may improve endothelial function in some individuals with T2D [43]. The effects of GLP-1 on endothelial function have been reviewed by Sjöholm [44].

Interestingly, in preclinical studies, cardioprotective effects were apparent in GLP-1 receptor knockout mice, supporting the hypothesis that certain cardioprotective actions of GLP-1 are mediated through GLP-1 receptor-independent pathways [38].

Effects of incretin-based therapies on cardiovascular risk factors

People with T2D who are overweight or obese, are hypertensive or have dyslipidaemia are at increased risk of adverse CV events. Incretin-based therapies have been shown to have an impact on these CV risk factors; however, differences in these effects between DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists have been noted. These differences may arise from differences in mechanism of action, or levels of GLP-1 receptor activation produced by these individual drug classes [12].

Weight

Obesity increases the risk of CVD mortality in T2D [45]. As more than half of individuals with T2D are obese [46], weight control is an important aspect of CV risk management in T2D. Encouragingly, lifestyle and certain pharmacological interventions that promote weight loss in people with T2D can improve CV risk profiles [47, 48].

DPP-4 inhibitors do not have major effects on weight [12]. Sitagliptin has been associated with changes in body weight of between 0.0 and −1.5 kg [49–52]. Clinical studies examining saxagliptin have shown either dose-independent, numerical decreases (−0.11 to −1.8 kg) or increases (+0.5 to +0.8 kg) in body weight [53–56]. Meanwhile, vildagliptin treatment has been associated with minimal weight gain of 0.2–1.3 kg [57].

In randomized controlled trials, use of the GLP-1 receptor agonists exenatide, liraglutide, or lixisenatide has been associated with body weight reductions. Exenatide BID treatment has been associated with average weight losses of up to 2.8 kg [58–60], and exenatide LAR with mean weight losses of up to 3.7 kg [61–66]. Similarly, in the GetGoal phase 3 development programme, lixisenatide was associated with mean body weight reductions of up to 3.0 kg [67–75], although not all observed weight changes were statistically different from comparators (placebo, exenatide) [67, 69, 70, 75]. In the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes (LEAD) phase 3 clinical trials, consistent, significant improvements in body weight were observed with liraglutide use versus comparator arms, with average weight losses of up to 3.2 kg [76–81].

Head-to-head trials comparing exenatide LAR [62, 64] or liraglutide [82–84] with sitagliptin have confirmed significantly greater changes in weight with the GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Blood pressure

Hypertension is a risk factor for adverse CV events, raising the risk of coronary heart disease by approximately 2-fold and the risk of stroke by 2- to 4-fold [85, 86].

Relatively few studies have examined the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on blood pressure in people with T2D. Limited evidence suggests that sitagliptin may reduce systolic blood pressure (SBP) [83, 87, 88], although this effect has not been observed across all studies [89]. Pooled data from six phase 3 clinical trials indicated similar small decreases in SBP and DBP with linagliptin 5 mg once daily and placebo [90].

The clinically available GLP-1 receptor agonists reduce SBP [12, 25]. In phase 3, placebo-controlled studies of lixisenatide, reductions of up to 2.1 mmHg were observed [25]. In the case of exenatide BID, reductions in SBP of 3.5 mmHg have been observed, with the greatest improvements seen in those who lost most weight (−8.1 mmHg in 25% of subjects) [91]. Liraglutide treatment was associated with reductions in SBP of up to 6.7 mmHg across the LEAD phase 3 development programme [76–82]. Interestingly, the reductions in SBP observed with liraglutide were observed prior to major weight loss, suggesting that SBP reduction does not occur solely via weight reduction [92]. As would be predicted, meta-analysis of the liraglutide phase 3 trials showed that individuals with the highest baseline SBP (>140 mmHg) exhibited the greatest reductions in SBP (−11.4 mmHg) [93], and that these reductions in SBP were independent of antihypertensive treatment [94].

Weight loss (discussed above), natriuresis and vasodilation [95] are likely to contribute to the SBP-lowering effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. A recent mouse model study has linked GLP-1 receptor stimulation by liraglutide to cAMP/Epac2-dependent atrial natriuretic peptide release, which would be predicted to increase natriuresis and vasodilation, thereby lowering blood pressure [95]. Consistent with these observations, a GLP-1 receptor-dependent, nitric oxide- and endothelium-independent vasodilatory effect of GLP-1 has been identified in rat femoral artery preparations [96].

Lipid profiles and other CV risk markers

Elevated fasting triglycerides (TG) and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and reduced high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), are associated with increased risk of CVD [97].

DPP-4 inhibitors have been shown to have either no effects or minor effects on fasting lipid levels in people with T2D [90, 98, 99]; however, they may have an effect on postprandial lipids. Indeed, significant reductions in postprandial TG, apolipoprotein B-48 (ApoB-48, a LDL), very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C) and free fatty acids (FFAs) have been reported following sitagliptin treatment [postprandial area under the curve (AUC) reduced by 9.4, 7.8, 9.3 and 7.6%, respectively, p < 0.05 for all measurements vs. placebo] [100]. Postprandial TG and ApoB-48 reductions and have also been reported following vildagliptin treatment [incremental AUC −2.0 ± 0.8 (p = 0.011) and −0.6 ± 0.3 (p = 0.008), respectively] [101] and alogliptin treatment [incremental AUC −3.4 ± 0.7 (p < 0.001) and −0.9 ± 0.2 (p = 0.028), respectively] [102]. The effects of incretin-based therapies on postprandial hyperlipidaemia have been reviewed elsewhere by Ansar and colleagues [103].

While no lipid profile data have yet been published for lixisenatide, meta-analyses have shown overall improvements in fasting lipids with exenatide (BID and LAR) and liraglutide therapy. Liraglutide reduces LDL, FFA and TG levels (by 0.2, 0.09 and 0.2 mmol/L, respectively, p < 0.01) and exenatide BID decreases LDL levels (by 0.15 mmol/L, p < 0.05 [104]). Trends towards reductions in FFA and TG were also evident with exenatide, but these did not reach statistical significance [104]. Small decreases in HDL reported for both liraglutide and exenatide (0.04 and 0.05 mmol/L, respectively, p < 0.01) may not be clinically meaningful. No reductions in VLDL-C were observed for either GLP-1 receptor agonist [104].

Improvements in surrogate CV risk biomarkers, such as high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) have also been observed following treatment with liraglutide or exenatide BID [105–108].

Effects of incretin-based therapies on heart rate and cardiac repolarisation

Substantial resting heart rate elevation is associated with increased CV mortality, and drugs that prolong cardiac repolarisation carry a risk of provoking adverse CV events [109, 110]. What are the effects of incretin-based therapies on these parameters?

Heart rate

As resting heart rate elevation in excess of 10 beats per minute (bpm) has been positively correlated with CV and all-cause mortality [109], this should be evaluated when considering the CV safety profile of a drug.

A limited amount of data regarding the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on heart rate is available. Saxagliptin treatment has no apparent effect on heart rate [111]. Following high doses of linagliptin (100 mg), small increases in heart rate (>4 bpm compared with placebo) were observed. However, no meaningful changes in heart rate were observed in individuals who received therapeutic doses of linagliptin (5 mg) in the same study [112].

A randomised, double-blind crossover study of intravenous exenatide infusion (0.12 pmol/kg/min) versus placebo in 20 people with T2D and congestive heart failure identified acute and statistically significant increases in placebo-corrected heart rate of 9, 14 and 15 bpm after 1, 3 and 6 hours of exenatide infusion (0.12 pmol/kg/min), respectively [113]. However, in a separate evaluation of individuals with T2D (n = 54) treated chronically with exenatide BID for 12 weeks, heart rate was not significantly elevated above placebo (least square mean 2.1 ± 1.4 for exenatide vs. -0.7 ± 1.4 bpm for placebo, p = 0.16 [114]). Similarly, in one study of healthy volunteers, a transient increase in heart rate was observed with a therapeutic dose of lixisenatide (20 μg), but no mean increases in heart rate were observed with this GLP-1 receptor agonist in phase 3, placebo-controlled studies of individuals with T2D [25]. Studies of exenatide LAR have reported small but significant (p < 0.05) increases in heart rate from baseline (least square mean increase of 4 ± 1 bpm [63]) and liraglutide treatment has also been associated with increases in heart rate of 2–4 bpm [76, 77, 79, 81]. The mechanism behind the increase in heart rate observed with certain GLP-1 receptor agonists is not yet well understood. One possible explanation is that this is a compensation for the above-mentioned decrease in SBP.

QT interval

The electrocardiographic QT interval is a measure of cardiac repolarisation. An increased QT interval is a risk factor for torsades de pointes arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Hence, any drug that prolongs the QT interval may increase the risk of adverse CV events reviewed in [110].

The DPP-4 inhibitors sitagliptin [115], saxagliptin [101] and vildagliptin [116] are not associated with QT interval prolongation at clinically relevant concentrations in healthy individuals.

The effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on QTc interval, that is, corrected for heart rate, have been studied in healthy volunteers. In this population, liraglutide administration (0.6, 1.2. and 1.8 mg OD) produced no significant QTc prolongation [117]. A significant positive correlation between plasma exenatide concentration and QTc interval was reported in one study following single-dose administration of 10 μg exenatide in 62 healthy individuals [regression analysis slope (95% confidence interval; CI), 0.02 (0.01, 0.03), p < 0.001; change in QTcF (Fridericia correction) interval (90% prediction interval) estimated as 4.95 (2.64, 7.25) ms at geometric mean Cmax of exenatide] [118]. However, a further QT interval study in which exenatide was administered by intravenous infusion to achieve supratherapeutic plasma concentrations (up to ~630 pg/mL) was reassuring, indicating no QTc prolongation in a population of 74 healthy adults [119]. To date, the effects of lixisenatide on cardiac repolarisation have not been published.

Potential cardioprotective effects of incretin-based therapies

Consistent with the findings outlined above regarding a cardioprotective effect of native GLP-1 under ischaemic conditions, data from rodent and porcine models indicate that GLP-1 receptor agonists may limit infarct size following ischaemia-reperfusion injury [119–122]. A possible cardioprotective effect of exenatide following myocardial infarction has also been identified in a clinical setting. In people with ST-segment elevation MI undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention, intravenous exenatide administration at the time of reperfusion led to a reduction in the area of myocardium at risk, as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance 3 months after intervention [123]. A post hoc analysis tested the hypothesis that this effect would be more pronounced in those with short duration of ischaemia. Data from 148 participants were stratified according to median time from ambulance call or first contact with healthcare system to first balloon inflation (132 min). In subjects with short duration ischaemia (≤132 min), exenatide reduced final infarct size by 30% and increased myocardial salvage index by 14%; in contrast, no such effects were observed in those longer duration ischaemia (>132 min) [124]. Taken together, these findings highlight a potential cardioprotective effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists in the setting of myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury, provided they are administered early.

Long-term effects of incretin-based therapies on cardiovascular disease

Incretin-based therapies were amongst the first T2D treatments for which detailed evaluation of long-term CV safety was encouraged under the 2008 FDA guidance [11]. This guidance recommends that, with regard to the risk ratio for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), pre-approval clinical trials should demonstrate that the upper boundary of the two-sided 95% CI is less than 1.8 versus the control group, with subsequent outcomes trials indicating a two-sided 95% CI for risk ratio of less than 1.3 [11].

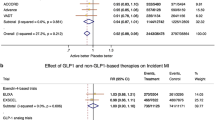

MACE analyses carried out for sitagliptin [125], saxagliptin [111] and alogliptin [126] have not indicated increased CV risk. Consistent with these findings, a recent meta-analysis identified no increased risk of CV events with a pooled group of DPP-4 inhibitors added to metformin versus metformin monotherapy [relative risk (95% CI) 0.54 (0.25-1.19), p = 0.13] [127]. Indeed, DPP-4 monotherapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of CV events than metformin monotherapy [relative risk (95% CI) 0.36 (0.15–0.85), p = 0.0.2], indicating a possible CV benefit of DPP-4 inhibitors [127]. Additionally, linagliptin has been associated with significantly fewer CV events than glimepiride over a 2-year period [both in combination with metformin ± one additional oral antidiabetic drug; relative risk (95% CI): 0.46 (0.23–0.91), p = 0.0213], despite similar reductions in mean HbA1c[128].

MACE analyses conducted for GLP-1 receptor agonists have similarly reported values within the FDA predefined safety limits for diabetes therapies. One meta-analysis of results from randomised trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists (exenatide BID, exenatide LAR, liraglutide, albiglutide) for the period up to November 2010 indicated the following cardiovascular safety margins [Mantel-Haenszel odds ratio for MACE (95% CI)]: all GLP-1 receptor agonists 0.74 (0.50–1.08), p = 0.12; exenatide 0.85 (0.50-1.45), p = 0.55; liraglutide 0.69 (0.40–1.22), p = 0.20 [129]. An as-yet-unpublished meta-analysis of eight, phase 3 studies of lixisenatide indicated a hazard ratio (95% CI) for adjudicated MACE of 1.03 (0.64, 1.66) versus placebo [25]. For liraglutide, retrospective MACE analysis of pooled data from all completed phase 2 and phase 3 randomised trials to date, plus all open-label trial extensions, indicated that the incidence ratio for broad/serious adjudicated MACE versus comparator drugs (metformin, glimepiride, rosiglitazone, insulin glargine) and placebo was 0.73 (95% CI 0.38, 1.41) [130].

These pooled data, mostly from phase 2 and 3 trials, are complemented by reassuring observational data. For example, a retrospective analysis of the U.S. LifeLink™ database of medical and pharmaceutical insurance claims (for the period June 2005 to March 2009) indicated that exenatide BID was not associated with an excess CV risk compared to other glucose-lowering therapies [131]. Consistent with this, another retrospective analysis found no elevated risk of MACE with exenatide BID compared to insulin for ≤1 year [132].

The long-term CV safety and efficacy of many incretin-based therapies are being prospectively evaluated in randomised control trials (Table 1). With the exception of the EXSCEL study, all include people with pre-existing CV disease and/or people with high risk for CV disease [16–24]. As of September 2013, a body of evidence is beginning to emerge on the long-term CV safety profile of incretin-based therapies in individuals at high risk of CV events: the results of the first two trials (SAVOR-TIMI 53 [saxagliptin] [22] and EXAMINE (alogliptin [24]), published as this article went to press, meet the FDA criteria for non-inferiority of these agents over placebo but provide no positive evidence of CV risk reduction. More evidence is eagerly awaited to inform clinical decision-making when seeking to minimise the risk of CVD in people with T2D.

Conclusions

In addition to their glucose-lowering properties, incretin-based therapies have apparently beneficial effects on CV risk factors, accompanied by small effects on heart rate, without clinically meaningful QTc prolongation. There is mechanistic evidence to suggest that GLP-1 receptor agonists may confer cardioprotective effects following ischaemia. Retrospective MACE analyses conducted for the different incretin based therapies have been reassuring. However, as mandated by regulatory agencies, the long-term CV safety of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists is currently under investigation in large CV outcomes trials. The results – which will emerge over the next few years – may also provide data on the efficacy of incretin-based agents in preventing CV events. This information will supply the evidence needed to position the use of these classes rationally amongst other more established glucose-lowering therapies.

Abbreviations

- ApoB-48:

-

Apolipoprotein B-48

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BID:

-

Twice daily

- BNP:

-

B-type natriuretic peptide

- bpm:

-

Beats per minute

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DPP-4:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- FDA:

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FFA:

-

Free fatty acid

- GIP:

-

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- hsCRP:

-

High sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LAR:

-

Long-acting release

- LEAD:

-

Liraglutide effect and action in diabetes

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- OD:

-

Once daily

- PAI-1:

-

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- QTc:

-

Heart rate-corrected QT interval

- QTcF:

-

Fridericia correction QT interval

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- VLDL-C:

-

Very low density lipoprotein cholesterol.

References

Fact sheet 312, diabetes. World health organization. 2012,http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/.

Mak KH, Moliterno DJ, Granger CB, Miller DP, White HD, Wilcox RG, Califf RM, Topol EJ, for the GUSTO-I Investigators: Influence of diabetes mellitus on clinical outcome in the thrombolytic era of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997, 30: 171-179. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00118-6.

Lind M, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Booth GL, Cea-Soriano L, Shah BR, Ekeroth G, Lipscombe LL: Mortality trends in patients with and without diabetes in Ontario, Canada and the UK from 1996 to 2009: a population-based study. Diabetologia. 2013, 10.1007/s00125-013-2949-2.

Aryangat AV, Gerich JE: Type 2 diabetes: postprandial hyperglycemia and increased cardiovascular risk. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010, 6: 145-155.

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, Hadden D, Turner RC, Holman RR: Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000, 321 (7258): 405-412. 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405.

Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Buse JB, Goff DC, Probstfield JL, Cushman WC, Ginsberg HN, Bigger JT, Grimm RH, Byington RP, Rosenberg YD, Friedewald WT, ACCORD Study Group: Long-term effects of intensive glucose lowering on cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2011, 364 (9): 818-828.

Singh S, Loke YK, Furberg CD: Thiazolidinediones and heart failure: a teleo-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2007, 30: 2148-2153. 10.2337/dc07-0141.

Singh S, Loke YK, Furberg CD: Long-term risk of cardiovascular events with rosiglitazone: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007, 298: 1189-1195. 10.1001/jama.298.10.1189.

MHRA. 2010,http://www.mhra.gov.uk/NewsCentre/Pressreleases/CON094127.

Graham DJ, Ouellet-Hellstrom R, MaCurdy TE, Ali F, Sholley C, Worrall C, Kelman JA: Risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in elderly medicare patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone. JAMA. 2010, 304: 411-418. 10.1001/jama.2010.920.

FDA. 2008,http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071627.pdf.

White J: Efficacy and safety of incretin based therapies: clinical trial data. Assoc J Am Pharm (2003). 2009, 49 (1): S30-S40.

Jellinger PS: Focus on incretin-based therapies: targeting the core defects of type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med. 2011, 123: 53-65. 10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2245.

Roche: Media release. 2011,http://www.roche.com/med-cor-2011-02-02-e.rtf.

Ray KK, Petrie J, Bengus M, Bengus M, Ekman S, Dixon M, Herz M, Buse J: Individual participant meta analysis of the cardiovascular safety of taspoglutide among individuals with diabetes. Circulation. 2012, 126 (21 Suppl): A15282

T-EMERGE-8.http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01018173.

Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, Hirshberg B, Ohman P, Frederich R, Wiviott SD, Hoffman EB, Cavender MA, Udell JA, Desal NR, Mozenson O, McGuire DK, Ray KK, Leiter LA, Raz I, the SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators: Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013, 10.1053/NEJMoa1307684.

White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, Nissen SE, Bergenstal RM, Bakris G, Perez AT, Fleck PR, Mehta CR, Kupfer S, Wilson C, Cushman WC, Zannad F, the EXAMINE Investigators: Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013, 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889.

Lyxumia® summary of product characteristics. Paris, France: sanofi-aventis groupe.http://www.sanofi.co.uk/l/gb/en/download.jsp?file=1B4E8D41-8F6C-4399-8C64-338ECDC0CA5A.pdf.

Baggio LL, Drucker DJ: Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132: 2131-2157. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054.

Bagger JI, Knop FK, Lund A, Vestergaard H, Holst JJ, Vilsbøll T: Impaired regulation of the incretin effect in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 96: 737-745. 10.1210/jc.2010-2435.

Nauck M, Stöckmann F, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W: Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia. 1986, 29: 46-52. 10.1007/BF02427280.

Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, Holst JJ, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W: Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7–36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1993, 91: 301-307. 10.1172/JCI116186.

Vilsbøll T, Krarup T, Deacon CF, Madsbad S, Holst JJ: Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon-like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2001, 50: 609-613. 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.609.

Nauck MA, Vardarli I, Deacon CF, Holst JJ, Meier JJ: Secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in type 2 diabetes: what is up, what is down?. Diabetologia. 2011, 54 (1): 10-18. 10.1007/s00125-010-1896-4.

Larsen J, Hylleberg B, Ng K, Damsbo P: Glucagon-like peptide-1 infusion must be maintained for 24 h/day to obtain acceptable glycemia in type 2 diabetic patients who are poorly controlled on sulphonylurea treatment. Diabetes Care. 2001, 24: 1416-1421. 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1416.

European medicines agency. 2011,http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002020/human_med_001457.jsp&murl=menus/medicines/medicines.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d125.

FDA. 2012,http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022200Orig1s000lbledt.pdf.

Vila Petroff MG, Egan JM, Wang X, Sollott SJ: Glucagon-like peptide-1 increases cAMP but fails to augment contraction in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001, 89: 445-452. 10.1161/hh1701.095716.

Gros R, You X, Baggio LL, Kabir MG, Sadi AM, Mungrue IN, Parker TG, Huang Q, Drucker DJ, Husain M: Cardiac function in mice lacking the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. Endocrinology. 2003, 144: 2242-2252. 10.1210/en.2003-0007.

Anagnostis P, Athyros VG, Adamidou F, Panagiotou A, Kita M, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP: Glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies and cardiovascular disease: looking beyond glycaemic control. Diab Obes Metab. 2011, 13: 302-312. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01345.x.

Ban K, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Hoefer J, Bolz SS, Drucker DJ, Husain M: Cardioprotective and vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor are mediated through both glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. Circulation. 2008, 117: 2340-2350. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739938.

Wei Y, Mojsov S: Tissue-specific expression of the human receptor for glucagon-like peptide-I: brain, heart and pancreatic forms have the same deduced amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett. 1995, 358: 219-224. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01430-9.

Erdogdu O, Nathanson D, Sjöholm A, Nyström T, Zhang Q: Exendin-4 stimulates proliferation of human coronary artery endothelial cells through eNOS-, PKA- and PI3K/Akt-dependent pathways and requires GLP-1 receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010, 325 (1–2): 26-35.

Nikolaidis LA, Mankad S, Sokos GG, Miske G, Shah A, Elahi D, Shannon RP: Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction after successful reperfusion. Circulation. 2004, 109: 962-965. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120505.91348.58.

Treiman M, Elvekjaer M, Engstrøm T, Jensen JS: Glucagon-like peptide 1 – a cardiologic dimension. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2010, 20: 8-12. 10.1016/j.tcm.2010.02.012.

Nyström T, Gutniak MK, Zhang Q, Zhang F, Holst JJ, Ahrén B, Sjöholm A: Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 287 (6): E1209-E1215. 10.1152/ajpendo.00237.2004.

Sjöholm A: Impact of glucagon-like peptide-1 on endothelial function. Diab Obes Metab. 2009, 11 (Suppl 3): 19-25.

Logue J, Walker JJ, Leese G, Lindsay R, McKnight J, Morris A, Philip S, Wild S, Sattar N, on behalf of The Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group: The association between BMI measured within a year after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and mortality. Diabetes Care. 2012, 36 (4): 887-893.

Scottish Diabetes Survey Monitoring Group: Scottish diabetes survey. 2011,http://www.diabetesinscotland.org.uk/Publications/SDS%202011.pdf.

Ratner R, Goldberg R, Haffner S, Marcovina S, Orchard T, Fowler S, Temprosa M, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group: Impact of intensive lifestyle and metformin therapy on cardiovascular disease risk factors in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 888-894.

Horton ES, Silberman C, Davis KL, Berria R: Weight loss, glycemic control, and changes in cardiovascular biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving incretin therapies or insulin in a large cohort database. Diabetes Care. 2010, 33: 1759-1765. 10.2337/dc09-2062.

Rosenstock J, Brazg R, Andryuk PJ, Lu K, Stein P, Sitagliptin Study 019 Group: Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing pioglitazone therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Clin Ther. 2006, 28: 1556-1568. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.007.

Goldstein BJ, Feinglos MN, Lunceford JK, Johnson J, Williams-Herman DE, Sitagliptin 036 Study Group: Effect of initial combination therapy with sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, and metformin on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007, 30: 1979-1987. 10.2337/dc07-0627.

Nauck MA, Meininger G, Sheng D, Terranella L, Stein PP, Sitagliptin Study 024 Group: Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, compared with the sulfonylurea, glipizide, in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin alone: a randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007, 9: 194-205. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00704.x.

Hermansen K, Kipnes M, Luo E, Fanurik D, Khatami H, Stein P, Sitagliptin Study 035 Group: Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, sitagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on glimepiride alone or on glimepiride and metformin. Diab Obes Metab. 2007, 9 (5): 733-745. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00744.x.

Rosenstock J, Sankoh S, List JF: Glucose-lowering activity of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor saxagliptin in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Obes Metab. 2008, 10: 376-386. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00876.x.

Chacra AR, Tan GH, Apanovitch A, Ravichandran S, List J, CHen R, CV181-040 Investigators: Saxagliptin added to a submaximal dose of sulphonylurea improves glycaemic control compared with uptitration of sulphonylurea in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2009, 63: 1395-1406. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02143.x.

DeFronzo RA, Hissa MN, Garber AJ, Luiz Gross J, Yuyan Duan R, Ravichandran S, Chen RS, Saxagliptin 014 Study Group: The efficacy and safety of saxagliptin when added to metformin therapy in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes with metformin alone. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32: 1649-1655. 10.2337/dc08-1984.

Jadzinsky M, Pfützner A, Paz-Pacheco E, Xu Z, Allen E, Chen R, CV181-039 Investigators: Saxagliptin given in combination with metformin as initial therapy improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with either monotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Diab Obes Metab. 2009, 11: 611-622. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01056.x.

Mathieu C, Degrande E: Vildagliptin: a new oral treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008, 4: 1349-1360.

DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD: Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 1092-1100. 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1092.

Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD, Exenatide-113 Clinical Study Group: Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 2628-2635. 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2628.

Kendall DM, Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Zhuang D, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD: Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin and a sulfonylurea. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 1083-1091. 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1083.

Drucker DJ, Buse JB, Taylor K, Trautmann M, Zhuang D, Porter L, DURATION-1 Study Group: Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2008, 372 (9645): 1240-1250. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61206-4.

Bergenstal RM, Wysham C, Macconell L, Malloy J, Walsh B, Yan P, Wilhelm K, Malone J, Porter LE, DURATION-2 Study Group: Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus sitagliptin or pioglitazone as an adjunct to metformin for treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION-2): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010, 376 (9739): 431-439. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60590-9.

Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, Northrup J, Cao D, Taylor K, Trautmann M: Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010, 375 (9733): 2234-2243. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60406-0.

Boardman MK, Hanefeld M, Kumar A, Gonzalez JG, de Teresa L, Northrup J, Chan M, Russell-Jones DL: DURATION-4: improvements in glucose control and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide once weekly, metformin, pioglitazone, or sitagliptin. Diabetologia. 2011, 54 (1): S314-Abstract 779

Blevins T, Pullman J, Malloy J, Yan P, Taylor K, Schulteis C, Trautmann M, Porter L: DURATION-5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 96: 1301-1310. 10.1210/jc.2010-2081.

Buse JB, Nauck MA, Forst T, Sheu WHH, Hoogwerf BJ, Shenouda SK, Heilmann CR, Boardman MK, Fineman M, Porter L, Schernthaner G: Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-6): a randomised, open-label study. Diabetologia. 2011, 54 (1): S38-Abstract 75

Fonseca VA, Alvarado-Ruiz R, Raccah D, Boka G, Miossec P, Gerich JE, EFC6018 GetGoal-Mono Study Investigators: Efficacy and safety of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in monotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes (GetGoal-mono). Diabetes Care. 2012, 35: 1225-1231. 10.2337/dc11-1935.

Bolli GB, Munteanu M, Dotsenko S, Niemoeller E, Boka G, Hanefeld M: Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once-daily versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus insufficiently controlled on metformin (GetGoal-F1). Diabetologia. 2011, 54 (1): S316-Abstract 784-P

Ahren B, Leguizamo Dimas A, Miossec P, Saubadu S, Aronson R, IDF: DF 2011 21th world congress abstract book. 2011, Dubai: IDF, 193-Oral 0591

Rosenstock J, Raccah D, Koranyi L, Maffei L, Boka G, Miossec P, Gerich JE: Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once-daily vs exenatide twice-daily in type 2 DM inadequately controlled on metformin (GetGoal-X). Diabetes. 2011, 60 (1A): LB10-33-LB

Pinget M, Goldenberg R, Niemoeller E, Muehlen-Bartmer I, Aronson R: Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on pioglitazone (GetGoal-P). Diabetes. 2012, 55 (1): 1010-P.

Ratner RE, Hanefeld M, Shamanna P, Min K, Boka G, Miossec P, Muehlen-Bartmer I, Rosenstock J: Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once-daily versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus insufficiently controlled on sulfonylurea ± metformin (GetGoal-S). Diabetologia. 2011, 54 (1): S317-Abstract 785-P

Rosenstock J, Forst T, Aronson R, Sauque-Reyna L, Souhami E, Ping L, Riddle MC: Efficacy and safety of once-daily lixisenatide added on to titrated glargine plus oral agents in type 2 diabetes: GetGoal-Duo 1 study. Diabetes. 2012, 61 (1): 62-OR.

Riddle MC, Home P, Marre M, Niemoeller E, Ping L, Rosenstock J: Efficacy and safety of once-daily lixisenatide in type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled with basal insulin ± metformin: GetGoal-L study. Diabetes. 2012, 61 (1): 983-P.

Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A, EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diab Obes Metab. 2012, 14: 910-917. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

Marre M, Shaw J, Brändle M, Bebakar WM, Kamaruddin NA, Strand J, Zdravkovic M, Le Thi TD, Colagiuri S, LEAD-1 SU study group: Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009, 26: 268-278. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02666.x.

Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, Shah NS, Tankova T, Mitha IH, Zdravkovic M, Düring M, MAtthews DR, LEAD-2 Study Group: Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32: 84-90. 10.2337/dc08-1355.

Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, Garcia-Hernandez PA, Rodriguez-Pattzi H, Olvera-Alvarez I, Hale PM, Zdravkovic M, Bode B, LEAD-3 (Mono) Study Group: Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9662): 473-481. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5.

Zinman B, Gerich J, Buse JB, Lewin A, Schwartz S, Raskin P, Hale PM, Zdravkovic M, Blonde L, LEAD-4 Study Investigators: Efficacy and safety of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide in combination with metformin and thiazolidinedione in patients with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-4 Met + TZD). Diabetes Care. 2009, 32: 1224-1230. 10.2337/dc08-2124.

Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, Sethi BK, Lalic N, Antic S, Zdravkovic M, Ravn GM, Simó R, Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes 5 (LEAD-5) met + SU Study Group: Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met + SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009, 52: 2046-2055. 10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y.

Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, Schmidt WE, Montanya E, Brett JH, Zychma M, Blonde L, LEAD-6 Study Group: Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet. 2009, 374 (9683): 39-47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60659-0.

Pratley RE, Nauck M, Bailey T, Montanya E, Cuddihy R, Filetti S, Thomsen AB, Søndergaard RE, Davies M, 1860-LIRA-DPP-4 Study Group: Liraglutide versus sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have adequate glycaemic control with metformin: a 26-week, randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Lancet. 2010, 375 (9724): 1447-1456. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60307-8.

Pratley R, Nauck M, Bailey T, Montanya E, Cuddihy R, Filetti S, Garber A, Thomsen AB, Hartvig H, Davies M, 1860-LIRA-DPP-4 Study Group: One year of liraglutide treatment offers sustained and more effective glycaemic control and weight reduction compared with sitagliptin, both in combination with metformin, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2011, 65: 397-407. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02656.x.

Niswender K, Pi-Sunyer X, Buse J, Jensen KH, Toft AD, Russell-Jones D, Zinman B: Weight change with liraglutide and comparator therapies: an analysis of seven phase 3 trials from the liraglutide diabetes development programme. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013, 15: 42-54. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01673.x.

Padwal R, Straus SE, McAlister FA: Evidence based management of hypertension. Cardiovascular risk factors and their effects on the decision to treat hypertension: evidence based review. BMJ. 2001, 322 (7292): 977-980. 10.1136/bmj.322.7292.977.

Ferrannini E, Cushman WC: Diabetes and hypertension: the bad companions. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9841): 601-610. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60987-8.

Ogawa S, Ishiki M, Nako K, Okamura M, Senda M, Mori T, Ito S: Sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, decreases systolic blood pressure in Japanese hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2011, 223: 133-135. 10.1620/tjem.223.133.

Kubota A, Maeda H, Kanamori A, Matoba K, Jin Y, Minagawa F, Obana M, Iemitsu K, Ito S, Amemiya H, Kaneshiro M, Takai M, Kaneshige H, Hoshino K, Ishikawa M, Minami N, Takuma T, Sasai N, Aoyagi S, Kawata T, Mokubo A, Takeda H, Honda S, Machimura H, Motomiya T, Waseda M, Naka Y, Tanaka Y, Terauchi Y, Matsuba I: Pleiotropic effects of sitagliptin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Clin Med Res. 2012, 4: 309-313.

Koren S, Shemesh-Bar L, Tirosh A, Peleg RK, Berman S, Hamad RA, Vinker S, Golik A, Efrati S: The effect of sitagliptin versus glibenclamide on arterial stiffness, blood pressure, lipids, and inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012, 14: 561-567. 10.1089/dia.2011.0296.

von Eynatten M, Gong Y, Emser A, Woerle HJ: Efficacy and safety of linagliptin in type 2 diabetes subjects at high risk for renal and cardiovascular disease: a pooled analysis of six phase III clinical trials. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013, 12: 60-10.1186/1475-2840-12-60.

Klonoff DC, Buse JB, Nielsen LL, Guan X, Bowlus CL, Holcombe JH, Wintle ME, Maggs DG: Exenatide effects on diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular risk factors and hepatic biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes treated for at least 3 years. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008, 24: 275-286.

Gallwitz B, Vaag A, Falahati A, Madsbad S: Adding liraglutide to oral antidiabetic drug therapy: onset of treatment effects over time. Int J Clin Pract. 2010, 64: 267-276.

Fonseca V, Falahati A, Zychma M, Madsbad S, Plutzky J: Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, reduces systolic blood pressure within 2 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes. 2009, Montreal: IDF 2009 20th World Congress Abstract Book. IDF, 310-Poster D-0908

Fonseca V, Plutzky J, Montanya E, Colagiuri S, Hansen CT, Falahati A, DeVries JH: Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analog, lowers systolic blood pressure (SBP) independently of concomitant antihypertensive treatment. Diabetes. 2010, 59 (1): A78-Abstract 296-OR

Kim M, Platt MJ, Shibasaki T, Quaggin SE, Backx PH, Seino S, Simpson JA, Drucker DJ: GLP-1 receptor activation and Epac2 link atrial natriuretic peptide secretion to control of blood pressure. Nat Med. 2013, 19 (5): 567-575. 10.1038/nm.3128.

Nyström T, Gonon AT, Sjöholm A, Pernow J: Glucagon-like peptide-1 relaxes rat conduit arteries via an endothelium-independent mechanism. Regul Pept. 2005, 125 (1–3): 173-177.

Miller M: Dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk: the importance of early prevention. QJM. 2009, 102: 657-667. 10.1093/qjmed/hcp065.

Sharma MD: Role of saxagliptin as monotherapy or adjunct therapy in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010, 6: 233-237.

Amori RE, Lau J, Pittas AG: Efficacy and safety of incretin therapy in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007, 298: 194-206. 10.1001/jama.298.2.194.

Tremblay AJ, Lamarche B, Deacon CF, Weisnagel SJ, Couture P: Effect of sitagliptin therapy on postprandial lipoprotein levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011, 13: 366-373. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01362.x.

Matikainen N, Mänttäri S, Schweizer A, Ulvestad A, Mills D, Dunning BE, Foley JE, Taskinen MR: Vildagliptin therapy reduces postprandial intestinal triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006, 49: 2049-2057. 10.1007/s00125-006-0340-2.

Eliasson B, Möller-Goede D, Eeg-Olofsson K, Wilson C, Cederholm J, Fleck P, Diamant M, Taskinen MR, Smith U: Lowering of postprandial lipids in individuals with type 2 diabetes treated with alogliptin and/or pioglitazone: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2012, 55 (4): 915-925. 10.1007/s00125-011-2447-3.

Ansar S, Koska J, Reaven PD: Postprandial hyperlipidemia, endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk: focus on incretins. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011, 10: 61-10.1186/1475-2840-10-61.

Plutzky J, Garber A, Toft AD, Toft AD, Poulter NR: Meta-analysis demonstrates that liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, significantly reduces lipids and other markers of cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009, 52 (Suppl. 1): S299.

Plutzky J, Poulter NR, Falahati A, Toft A, Davidson MH: Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is reduced by the once-daily human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide when used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2009, 120 (Suppl. 2): S397.

Varanasi A, Patel P, Makdissi A, Dhindsa S, Chaudhuri A, Dandona P: Clinical Use of liraglutide in type 2 diabetes, and its effects on cardiovascular risk factors. Endocr Pract. 2012, 18: 140-145. 10.4158/EP11169.OR.

Varanasi A, Chaudhuri A, Dhindsa S, Arora A, Lohano T, Vora MR, Dandona P: Durability of effects of exenatide treatment on glycemic control, body weight, systolic blood pressure, C-reactive protein, and triglyceride concentrations. Endocr Pract. 2011, 17: 192-200. 10.4158/EP10199.OR.

Forst T, Michelson G, Ratter F, Weber MM, Anders S, Mitry M, Wilhelm B, Pfützner A: Addition of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes well controlled on metformin monotherapy improves several markers of vascular function. Diabet Med. 2012, 29: 1115-1118.

Jensen MT, Marott JL, Allin KH, Nordestgaard BG, Jensen GB: Resting heart rate is associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality after adjusting for inflammatory markers: the Copenhagen city heart study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012, 19: 102-108. 10.1177/1741826710394274.

van Noord C, Eijgelsheim M, Stricker BH: Drug- and non-drug-associated QT interval prolongation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010, 70: 16-23. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03660.x.

Saxagliptin FDA briefing document.http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/EndocrinologicandMetabolicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM148109.pdf.

Ring A, Port A, Graefe-Mody EU, Revollo I, Iovino M, Dugi KA: The DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin does not prolong the QT interval at therapeutic and supratherapeutic doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011, 72: 39-50. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03931.x.

Nathanson D, Ullman B, Löfström U, Hedman A, Frick M, Sjöholm A, Nyström T: Effects of intravenous exenatide in type 2 diabetic patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind, randomised controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Diabetologia. 2012, 55 (4): 926-935. 10.1007/s00125-011-2440-x.

Gill A, Hoogwerf BJ, Burger J, Bruce S, Macconell L, Yan P, Braun D, Giaconia J, Malone J: Effect of exenatide on heart rate and blood pressure in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2010, 9: 6-10.1186/1475-2840-9-6.

Bloomfield DM, Krishna R, Hreniuk D, Hickey L, Ghosh K, Bergman AJ, Miller J, Gutierrez MJ, Stoltz R, Gottesdiener KM, Herman GA, Wagner JA: A thorough QTc study to assess the effect of sitagliptin, a DPP4 inhibitor, on ventricular repolarization in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009, 49: 937-946. 10.1177/0091270009337511.

He YL, Zhang Y, Serra D, Wang Y, Ligueros-Saylan M, Dole WP: Thorough QT study of the effects of vildagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor, on cardiac repolarization and conduction in healthy volunteers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011, 27: 1453-1463. 10.1185/03007995.2011.585395.

Chatterjee DJ, Khutoryansky N, Zdravkovic M, Sprenger CR, Litwin JS: Absence of QTc prolongation in a thorough QT study with subcutaneous liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analog for treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009, 49: 1353-1362. 10.1177/0091270009339189.

Linnebjerg H, Seger M, Kothare PA, Hunt T, Wolka AM, Mitchell MI: A thorough QT study to evaluate the effects of single dose exenatide 10 μg on cardiac repolarization in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011, 49: 594-604. 10.5414/CP201462.

Darpö B, Sager P, Macconell L, Cirincione B, Mitchell M, Han J, Huang W, Malloy J, Schulteis C, Shen L, Porter L: Exenatide at therapeutic and supratherapeutic concentrations does Not prolong the QTc interval in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012, 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04416.x.

Noyan-Ashraf MH, Momen MA, Ban K, Sadi AM, Zhou YQ, Riazi AM, Baggio LL, Henkelman RM, Husain M, Drucker DJ: GLP-1R agonist liraglutide activates cytoprotective pathways and improves outcomes after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes. 2009, 58: 975-983. 10.2337/db08-1193.

Sonne DP, Engstrøm T, Treiman M: Protective effects of GLP-1 analogues exendin-4 and GLP-1(9–36) amide against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat heart. Regul Pept. 2008, 146: 243-249. 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.10.001.

Timmers L, Henriques JP, de Kleijn DP, Devries JH, Kemperman H, Steendijk P, Verlaan CW, Kerver M, Piek JJ, Doevendans PA, Pasterkamp G, Hoefer IE: Exenatide reduces infarct size and improves cardiac function in a porcine model of ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 53: 501-510. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.033.

Lønborg J, Vejlstrup N, Kelbæk H, Bøtker HE, Kim WY, Mathiasen AB, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Clemmensen P, Holmvang L, Thuesen L, Krusell LR, Jensen JS, Køber L, Treiman M, Holst JJ, Engstrøm T: Exenatide reduces reperfusion injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012, 33: 1491-1499. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr309.

Lønborg J, Kelbæk H, Vejlstrup N, Bøtker HE, Kim WY, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Terkelsen CJ, Schoos MM, Køber L, Clemmensen P, Treiman M, Engstrøm T: Exenatide reduces final infarct size in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction and short-duration of ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012, 5: 288-295. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.968388.

Williams-Herman D, Engel SS, Round E, Johnson J, Golm GT, Guo H, Musser BJ, Davies MJ, Kaufman KD, Goldstein BJ: Safety and tolerability of sitagliptin in clinical studies: a pooled analysis of data from 10,246 patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2010, 10: 7-10.1186/1472-6823-10-7.

White WB, Pratley R, Fleck P, Munsaka M, Hisada M, Wilson C, Menon V: Cardiovascular safety of the dipetidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor alogliptin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013, 15 (7): 668-673. 10.1111/dom.12093.

Wu D, Li L, Liu C: Efficacy and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and metformin as initial combination therapy and as monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013, 10.1111/dom.12174.

Gallwitz B, Rosenstock J, Rauch T, Bhattacharya S, Patel S, von Eynatten M, Dugi KA, Woerle HJ: 2-Year efficacy and safety of linagliptin compared with glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9840): 475-483. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60691-6.

Monami M, Cremasco F, Lamanna C, Colombi C, Desideri CM, Iacomelli I, Marchionni N, Mannucci E: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Exp Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011: 215764-10.1155/2011/215764.

Marso SP, Lindsey JB, Stolker JM, House JA, Martinez Ravn G, Kennedy KF, Jensen TM, Buse JB: Cardiovascular safety of liraglutide assessed in a patient-level pooled analysis of phase 2: 3 liraglutide clinical development studies. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2011, 8: 237-240. 10.1177/1479164111408937.

Best JH, Hoogwerf BJ, Herman WH, Pelletier EM, Smith DB, Wenten M, Hussein MA: Risk of cardiovascular disease events in patients with type 2 diabetes prescribed the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist exenatide twice daily or other glucose-lowering therapies: a retrospective analysis of the LifeLink database. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34: 90-95. 10.2337/dc10-1393.

Ratner R, Han J, Nicewarner D, Yushmanova I, Hoogwerf BJ, Shen L: Cardiovascular safety of exenatide BID: an integrated analysis from controlled clinical trials in participants with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011, 10: 22-10.1186/1475-2840-10-22.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Elien Moës and Laura Elson from Watermeadow Medical, Witney, UK (supported by Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) for their assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JP has received honoraria for lectures, travel support and consultancy services from pharmaceutical companies manufacturing diabetes treatments, including AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi-Aventis and Takeda. He serves on GLP-1 agonist clinical trial committees for Novo-Nordisk and Sanofi-Aventis. He is a recipient of support in kind from Merck-Serono for a JDRF-funded investigator-led study (REMOVAL, NCT01483560; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01483560).

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Petrie, J.R. The cardiovascular safety of incretin-based therapies: a review of the evidence. Cardiovasc Diabetol 12, 130 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-12-130

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-12-130