Abstract

Introduction

With the introduction of newer atypical antipsychotic agents, a question emerged, concerning their use as complementary pharmacotherapy or even as monotherapy in mental disorders other than psychosis.

Material and method

MEDLINE was searched with the combination of each one of the key words: risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine with key words that refered to every DSM-IV diagnosis other than schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and dementia and memory disorders. All papers were scored on the basis of the JADAD index.

Results

The search returned 483 papers. The selection process restricted the sample to 59 papers concerning Risperidone, 37 concerning Olanzapine and 4 concerning Quetiapine (100 in total). Ten papers (7 concerning Risperidone and 3 concerning Olanzapine) had JADAD index above 2. Data suggest that further research would be of value concerning the use of risperidone in the treatment of refractory OCD, Pervasive Developmental disorder, stuttering and Tourette's syndrome, and the use of olanzapine for the treatment of refractory depression and borderline personality disorder.

Discussion

Data on the off-label usefulness of newer atypical antipsychotics are limited, but positive cues suggest that further research may provide with sufficient hard data to warrant the use of these agents in a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders, either as monotherapy, or as an augmentation strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Newer antipsychotic agents exhibit a well documented beneficial effect on schizophrenia and psychosis in general. Their use in bipolar disorder is also well established. Also their use in the treatment of psychotic and behavioral disorders in the frame of dementia of various types may warrant further study.

However, in 1999, almost 70% of prescriptions concerned an off-label use of antipsychotics. Psychiatrists around the world used to apply low doses of antipsychotics to a variety of refractory non-psychotic patients, already during the pre-atypical era.

An earlier review paper by Potenza and McDougle [1] reported no hard evidence concerning the use of atypical antipsychotics in non-psychotic disorders. These authors traced several positive uncontrolled studies concerning risperidone, but also concluded that clozapine is rather not useful in non-psychotic cases. A more recent review by Schweitzer (2001) [2] does not address the literature systematically and mainly focuses on Obssessive-Compulsive disorder, dementia, bipolar disorder and psychotic depression.

The aim of the current study was to search the literature and review the data concerning the use of newer antipsychotics in other cases than psychotic disorders or dementia. The search was limited to Risperidone, Olanzapine and Quetiapine.

All these agents are potent serotonine (5-HT2A) and dopamine (D2) antagonist [3] with proven antipsychotic activity [4, 5], but their exact mode of action to produce their antipsychotic effect is still largely unknown [6, 7].

Material and Method

The MEDLINE was searched with the combination of each one of the key words risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine with key words that referred to every DSM-IV diagnosis other than schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, dementia and memory disorders.

These key-words were the following:

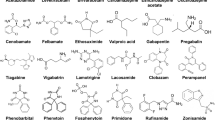

Anxiety, Agoraphobia, Anorexia, Autism, Body dysmorphic disorder, Boulimia, Conversion, Depression, Dissociative, Dysthymia, Explosive, Factitious, GAD, Gambling, Hypochondriasis, Impulse-control disorders, Kleptomania, Neurotic, Non-psychotic, OCD, Pain, Panic, Paraphilia, Parasomnia, Personality, Phobia, PTSD, Pyromania, Somatization, Somatoform, substance abuse, Tic, Trichotillomania.

All papers were scored on the basis of the Jadad index-Instrument to Measure the Likelihood of Bias in Pain Research Reports (table 1) [8].

Results

The MEDLINE search returned 483 papers. This number concerns June 2002.

Two hundred and forty four (244) of them concerned Risperidone, 181 concerned Olanzapine (+2 concerning its anti-vomiting action in cancer patients and +1 concerning the treatment of headache) and 58 papers concerned Quetiapine.

The selection process restricted the sample to 59 papers concerning Risperidone [9–67], 37 concerning Olanzapine [68–104], and 4 concerning Quetiapine [105–108] (100 in total). Only these 100 papers reported patient data of any kind (case-reports, open-label studies, double-blind studies)

Out of these 100 papers, 60 concerned adult psychiatry [8–11, 20, 26, 29, 31–35, 37, 40–45, 47, 48, 50, 53, 54, 56, 58–62, 67, 69–85, 87, 88, 91–94, 96–100, 102–105, 107], 36 child and adolescence psychiatry and 4 geriatric psychiatry.

The disorders with the higher number of papers were obsessive compulsive disorder (17 papers) [10, 19, 23, 27, 31, 32, 40, 41, 50, 54, 56, 60, 62, 72, 75, 85, 105], depression (16 papers) [34, 43, 47, 48, 61, 68, 70, 77, 84, 91, 94, 97–99, 103, 107], pervasive developmental disorder (15 papers) [14–18, 22, 28, 30, 38, 39, 42, 49, 52, 63, 66] and Tourette's syndrome (10 papers) [12, 13, 25, 55, 64, 71, 73, 92, 102, 108].

Ninety-one papers reported a beneficial result, 2 reported neither a positive nor a negative result [26, 74] and 7 papers reported worsening of the patients [10, 19, 27, 86, 91, 105, 106].

A detailed list of disorders, number of papers per disorder and agent, the reported outcome, the drug dosage and the source of financial support are presented in table 2.

The JADAD index was below 2 in 90 papers. Ten papers (7 concerning Risperidone [12, 15, 26, 37, 40, 42, 63] and 3 concerning Olanzapine [74, 99, 104]) had JADAD index above 2. The list of disorders by pharmaceutical agents and outcome are shown in table 3.

In fact, all double-blind studies received a score above 2 in the current review.

Analysis of reports

The statistics of the MEDLINE search results suggest that there are only a few papers that fulfill high scientific quality requirements. The number of experimental studies that provide any kind of data and not only assumptions is also limited. Thus, only 100 papers report observations on patients, and only 10 of them do this in a rigorous manner (fig 1).

The vast majority of papers (91 papers) reported a beneficial effect from the use of the specific agent in patients with the disorder. Two papers reported no beneficial effect while in 7 papers the outcome was the worsening of symptomatology. This of course could suggest that the accumulation of data lead to the conclusion that there is indeed a positive effect from the off-label use of atypical antipsychotics. However, even strongly established therapies do not reach a 90% effect. Thus, this is rather the effect of the 'file drawer' syndrome, that is, the tendency to publish positive and beneficial results and to forget negative ones. This syndrome affects both authors and journals, and leads to the following phenomenon: researchers chase positive results while negative ones are published only as a response to previously published positive ones.

In this frame, only the ten papers with Jadad score above 2 are of high value, and are discussed in detail in the present study [12, 15, 26, 37, 40, 42, 63, 74, 99, 104]. It is interesting to note that 7 of them concern risperidone, and 3 of them concern olanzapine. None concerns quetiapine. It seems that the number of papers largely reflect the years since the introduction of the agent in the market.

Tourette's syndrome

There is only 1 paper involving the use of risperidone in the treatment of Tourette's syndrome [12] by Bruggeman et al in 2001. This paper was supported by the Janssen Research Foundation (Beerse, Belgium) and was a multicenter one. It included an adequate double blind and randomized design (computer-generated randomization code, identical capsules and administration schedules for both agents), and a sufficient description of withdrawals and dropouts. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 5. The study included 50 patients (26 on risperidone and 24 on pimozide) and all were treated with flexible doses of up to 6 mg per os of each agent per day. Their age was 11–50 years and their age of onset was 3–16 years. Twenty-three had a comorbid OCD (14 in the pimozide treated group), 3 generalized anxiety disorder and 2 Attention deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The study period was 12-weeks long. At endpoint, the mean risperidone dose was 3.8 mg/day and the mean pimozide dose was 2.9 mg/day. The results suggested that risperidone is at least as effective as pimozide in the treatment of Tourette's disorder, with a comparable effect also on comorbid conditions and equal efficacy and safety for both children and adults.

Tourett's disorder is characterized by multiple motor and vocal tics with onset before the age of 18[109]. Comorbidity is common, with high frequency of comorbid ADHD, OCD, anxiety and depression. Thus, patients are usually treated with a combination of agents, with neuroleptics being effective for the treatment of tics. Haloperidol and particularly pimozide are the two most widely used compounds [110], but their use is restricted by the occurrence of side-effects. On the other hand, not all neuroleptics were proved effective. For example Clozapine is not[111].

Pervasive developmental disorder

There are 3 papers, all involving the use of risperidone in the treatment of pervasive developmental disorder [15, 42, 63].

a. The study of McDougle et al in 1998 [42] was supported by a number of research grants unrelated to the pharmaceutical industry. It included an adequate double blind and randomized design (computer-generated randomization code, identical capsules and administration schedules for both agents), and a sufficient description of withdrawals and dropouts. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 5. The study included 31 adults suffering from autism (N = 17) or pervasive developmental disorder NOS (N = 14) (9 women, 22 men) with at least 'moderate' severity of symptoms. Twenty-four (77%) had received previous treatment with psychotropic drugs. Their age was 28.1 ± 7.3 years. The study period was 12-weeks long, and 24 patients completed the study. At endpoint, the mean risperidone dose was 2.9 ± 1.4 mg/day. Eight (57% of the risperidone treated patients responded, compared with none of the placebo group. The results suggested that risperidone is significantly more effective than placebo for decreasing many of the interfering behavioral symptoms of adults with autism and PDD NOS. Specifically, risperidone was found effective for the treatment of repetitive behaviors and aggression towards self, others and property. Social relationships, language and sensory response did not improve. Treatment response was not related to diagnostic subtype, sex, treatment setting baseline scale scores, or dose of risperidone. Side effects were low in both groups and no significant differences were detected. Weight gain was observed in only 2 subjects of the risperidone group and was mild.

b. The study of Buitelaar et al in 2001 [15] was supported by the Janssen-Cilag BV, Tilburg, the Netherlands. Two centers participated. It included an adequate randomized design (computer-generated randomization code), but the double blind procedure did not included identical capsules and administration schedules for both agent and placebo. There was a sufficient description of withdrawals and dropouts. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 3. The study included 38 adolescents (33 boys, 10 with subaverage IQ, 14 with borderline IQ and 14 with mild mental retardation). Their age was 14.0 ± 1.5 years for the risperidone group and 13.7 ± 2.0 for the placebo group. and their age of onset was 3–16 years. The study period was 6-weeks long. At endpoint, the mean risperidone dose was 2.9 mg/day (range 1.5–4 mg/day), equivalent to 0.044 mg/kgr/day (range 0.019–0.080 mg/kgr/day). The results suggested that risperidone is significantly more effective than placebo in the treatment of pathologic aggression (and particularly of physical aggression and aggression to property at the ward and hyperactivity at school), with only 21% of risperidone treated patients being disturbed at endpoint in comparison to 84% of patients in the placebo group. Side effects were low in both groups and no significant differences were detected. The mean body weight increased by 2.3 kgr (3.5%) in the risperidone group in comparison to 0.6 kgr (1.1%) in the placebo group. A disadvantage of this study is the heterogeneous study sample and the short-term study period.

c. The study of Van Bellinghen and De Troch in 2001 [63] was supported by the Janssen Pharmaceutica, Berchem, Belgium. It included a randomized design (not described), and the double blind procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo (oral solution once daily). There were no withdrawals and dropouts to describe. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 3. The study included 13 patients (5 boys, 8 girls) with IQ, scores between 65 and 85. Their age was 10.5 (6–14) years for the risperidone group and 11 (7–14) for the placebo group. The study period was 4-weeks long. At endpoint, the mean risperidone dose was 1.2 mg/day, equivalent to 0.05 mg/kgr/day (range 0.03–0.06 mg/kgr/day). Antiepileptic medication was allowed during the trial. The results suggested that risperidone is significantly more effective than placebo for the treatment of irritation, hyperactivity and inappropriate speech. Side effects were mild and risperidone was well tolerated. Two risperidone-treated patients had their body weight increased by 7%.

Controlled trials suggest that typical antipsychotics like haloperidol are superior to placebo in the treatment of various symptoms of autism, like withdrawal, hyperactivity abnormal object relationships angry and labile affect[112]. Also, SSRI's may be effective for the controlling of interfering repetitive behavior and aggression, as well as enhancing social behavior [113–115].

Substance abuse

There is only 1 paper involving the use of risperidone in the treatment of substance abuse[26], by Grabowski et al in 2000. It was supported by NIDA grants. It included a randomized design (not described), and the double blind procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo. Withdrawals and dropouts are well described, and were due to adverse effects. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 3. The study included 125 uncomplicated cocaine-dependent patients with good medical health out of the 193 who were initially screened (74% male). Their age was 34.8 ± 7.0 years. The study period was 12-weeks long. At endpoint, no patient under 8 mg risperidone remained in the study, due to adverse effects. However, neither patients under 2 mg nor under 4 mg of risperidone showed significant improvement concerning cocaine abuse, neither in terms of discontinuation, nor in terms of reduced use.

It is true that thus far no agent was proved to be efficient for the treatment of drug abuse. There is a line of evidence suggesting that risperidone could be an ideal and efficient agent for this purpose. First of all, it has a dual action, both on 5-HT and dopamine systems. The selective 5-HT2 antagonist ritanserin was reported to reduce cocaine consumption in animals[116]. Antidopaminergic agents are supposed to be able to block intracerebral self-stimulation and cocaine-induced agitation and stereotypical behavior[117]. However, hard evidence are against this proposal. Many factors may be responsible for this failure. Patients may have increased their intake in order to overcome stimulation blockade by risperidone; higher but difficult to tolerate doses may be necessary to adequately block self-stimulation, or simply, the neurobiology of drug abuse is far more complex than the simplified model which predicted a favorable effect from the use of risperidone.

Stuttering

There is only 1 paper involving the use of risperidone in the treatment of stuttering[37], by Maguire et al, in 1999. There is no mention of supporting grants. It included a randomized design (not described), and the procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo, but is not described as blind. The description of the study however implies a blind procedure. No withdrawals nor dropouts were observed. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 3. The study included 21 patients suffering from a developmental form of stuttering (onset before the age of 6; 16 men and 5 women) with mild to very severe symptomatology. Their mean age was 40.75 years. The study period was 6-weeks long. At endpoint, the risperidone dose was below 2 mg per os daily. The results of this study suggest that the risperidone group showed a significant improvement concerning the severity of the symptomatology but not concerning the total time spent stuttering. In addition, no significant differences were detected concerning the comorbid cognitive impairment and social alienation-personal disorganization.

Obsessive Compulsive disorder (OCD)

There is only 1 paper involving the use of risperidone in the treatment of OCD[41], by McDougle et al, in 2000. It was supported by several State and independent grants. It included a randomized design (computer-generated list), and the double blind procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo. Withdrawals and dropouts are well described. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 5. The study included 36 refractory patients (21 male) suffering from OCD out of 70 initially screened. Their age was 24–59 years. The study period was 6-weeks long and included the comparison of two groups: one under SRI plus placebo and one under risperidone plus SRI. Placebo was used to make the administration procedure identical for both groups. The SRI dose was the equivalent of 80 mg of fluoxetine daily. At endpoint, the mean risperidone dose was 2.2 ± 0.7 mg per day. The results showed that half of the refractory OCD patients under the combination of risperidone with an SRI responded in comparison to no patient under the combination of risperidone and placebo. The difference was significant and included obsessive-compulsive, depressive and anxious symptomatology. No significant differences were found between OCD patients with and without comorbid chronic tic disorder or Schizotypal Personality. The most frequent side-effect was mild sedation.

Considering earlier reports, one might expect that an atypical antipsychotic would induce or exacerbate OCD symptoms. But these reports did not include true OCD patients, but rather psychotic patients with OCD symptoms. The standard therapy for OCD includes high doses of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs). The addition of agents that further enhance serotonin activity (e.g. lithium) in refractory patients did not solve the problem. On the contrary, the use of low-dose dopamine antagonists (e.g. haloperidol[118]) was effective but primarily in patients with comorbid tic disorders or schizotypal personality, which was not the case with the study reviewed here.

Post-Traumatic Stress disorder

There is only 1 paper involving the use of olanzapine in the treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress disorder[74], by Butterfield et al, in 2001. It was supported by Eli Lilly. It included a randomized design (not described), and the double blind procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo. Withdrawals and dropouts are well described. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 3. The study included 15 patients (14 female). All suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Comorbid diagnosis were Major Depression (N = 8), Generalized Anxiety disorder (N = 9) and Panic disorder (N = 8). Rape was the most common traumatic event (N = 8). Their age was 43.2 ± 14.7 years. The study period was 10-weeks long and included the comparison of two groups: one under olanzapine (N = 10), and one under placebo (N = 5). At endpoint, the mean olanzapine dose was 14.1 mg per day. There was no significant differences between olanzapine and placebo in terms of therapeutic response. A significant observation concerned the high placebo response. The main adverse effect was weight gain, averaging more than with 5.21 ± 2 kgr for the olanzapine treated patients over the study period vs. 0.40 ± 0.02 kgr for the placebo group. The authors report no efficacy of olanzapine for the treatment of PTSD, and suggest that further research is necessary with longer study periods (up to 6–9 months).

Depression

There is only 1 paper involving the use of olanzapine in the treatment of refractory non-psychotic depression[99] by Shelton et al in 2001. It was supported both by Eli Lilly and NIMH grants. It included a randomized design (not described), and the double blind procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo. Withdrawals and dropouts are well described. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 3. The study included 28 patients out of 34 initially screened (75% female). All suffered from unipolar non-psychotic treatment resistant depression. Their age was 42 ± 11 years. The study period was 8-weeks long and included the comparison of three groups: one under olanzapine monotherapy, one under fluoxetine monotherapy and one under a combination of both. Placebo was used to make the administration procedure identical for all groups. At endpoint, the mean fluoxetine dose was 52 mg per day for both groups and the mean olanzapine dose was 12.5 mg/day for the monotherapy group and 13.5 mg/day for the combination group. The combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine produced superior improvements over either agent alone. Either agent alone was ineffective in this population. Clinical response was evident by the first week. The main adverse effect was weight gain, averaging more than 6 kgr for the olanzapine treated patients over the double-blind period.

The possible mechanism for this favorable combined administration may lay in the fact that in animals the combined administration of fluoxetine and olanzapine increased by 269% the norepinephrine and by 349% the dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex. Olanzapine alone stabilizes and returns the levels to baseline, while fluoxetine alone increases them by 188% and 143% respectively[119].

Personality disorders

There is only 1 paper involving the use of olanzapine in the treatment of Borderline Personality disorder[104], by Zanarini et al in 2001. It was supported in part by a grant from Eli Lilly. It included a randomized design (random number sequence), and the double blind procedure included an identical procedure of administration for both agent and placebo. Withdrawals and dropouts are well described. Thus, it is given a Jadad score of 5. The study included 28 female patients. All suffered from borderline personality disorder with moderate severity of symptomatology, without comorbid affective or psychotic disorder. Their age was 27.6 ± 7.7 years for the olanzapine group and 25.8 ± 4.5 years for the placebo group. The study period was 6-months long. At endpoint, the mean olanzapine dose was 5.33 ± 3.43 mg per day. Side effects were few. Olanzapine showed greater efficacy than placebo in the treatment of anxiety, paranoia, impulsivity and interpersonal sensitivity, but not depression. The main adverse effects concerned minor sedation and weight gain, with 1.29 ± 2.56 kgr gained for the olanzapine treated patients while the placebo treated patients lost 0.78 ± 2.59 kgr.

Disadvantages of this study were the inclusion of women alone in the study sample; thus, generalization of results to men is questionable. Also, only 1 patient in the placebo group and 8 in the olanzapine group actually completed the entire 6-months period, thus disputing the magnitude of the therapeutic effect of olanzapine, and its true clinical usefulness.

Previous studies with typical antipsychotics[120, 121] produced equivocal results; those patients with more severe symptomatology or psychotic features seemed to benefit more. Side-effects restrict the use of these agents while their effect on the core of 'true' borderline symptoms (i.e. not on comorbid disorders) is unknown.

Discussion

Although the recommendation to use atypical antipsychotics in a variety of off-label situations is widespread in the literature, the current review proved that data are few and can not really support an evidence based recommendation. In fact, it is impressive that the number of papers without experimental data are four times more in comparison to the experimental ones, and forty times those with controlled double-blind methodology. Therefore, the landscape is not clear, and it is evident that further research is necessary. Also, it should be mentioned that all controlled studies reviewed in the current paper were published after the publication of the review of Potenza and McDougle [1].

What is encouraging is that of those 10 controlled studies, only about half were directly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, while the rest were independently supported. Thus, it is not likely that the intervention of pharmaceutical companies and thus the complication caused by conflicts of interest, would have enlarged the file drawer phenomenon. However this phenomenon is present and should be considered in order to arrive at reliable conclusions.

The current review suggests that there are some evidence that support the usefulness of atypical antipsychotics in some off-label situations. The generalization of these observations may be invalid. It is not proper to conclude that since one agent is effective, the others will be also.

There are preliminary data suggesting that further research would be of value concerning the use of risperidone in the treatment of refractory OCD, Pervasive Developmental disorder, stuttering and Tourette's syndrome, and the use of olanzapine for the treatment of refractory depression and borderline personality disorder.

In all studies side-effects were low, and sedation and fatigue were the most frequent reported. Weight gain was reported in some studies but it was not pronounced as long as the drug is applied at low doses (e.g. 2 mg of risperidone or 5 mg of olanzapine daily). On the contrary, when higher doses are involved, at least for olanzapine, weight gain tends to be more significant.

Conclusion

Data on the off-label usefulness of newer atypical antipsychotics are limited, but positive cues suggest that further research may provide with sufficient hard data to warrant the use of these agents in a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders, either as monotherapy, or as an augmentation strategy.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

Potenza MN, McDougle CJ: Potential of Atypical Antipsychotics in the Treatment of NonPsychotic Disorders. CNS Drugs. 1998, 9: 213-232.

Schweitzer I: Does Risperidone have a place in the treatment of nonschizophrenic patients?. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001, 1-19. 10.1097/00004850-200101000-00001.

Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Megens AA, Schotte A: Risperidone: a novel antipsychotic with balanced serotonin-dopamine antagonism, receptor occupancy profile, and pharmacologic activity. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994, 55 suppl: 5-12.

Chouinard G, Jones B, Remington G, Bloom D, Addington D, MacEwan GW, Labelle A, Beauclair L, W Arnot: A Canadian multicenter placebo-controlled study of fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1993, 25-40.

Marder SR, Meilbach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994, 151: 825-835.

Kapur S, Seeman P: Does fast dissociation from the dopamine D2 receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics?: A new hypothesis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 360-369. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.360.

Kapur S, Zipursky RB, Remington G: Clinical and theoretical implications of 5-HT2 and D2 receptor occupancy of clozapine, risperidone and olanzapine in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999, 156: 286-293.

Jadad A, Moore A, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Ad-Dab'bagh Y, Greenfield B, Milne-Smith J, Freedman H: Inpatient treatment of severe disruptive behaviour disorders with risperidone and milieu therapy. Can J Psychiatry. 2000, 45: 376-382.

Andrade C: Risperidone may worsen fluoxetine-treated OCD. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998, 59: 255-256.

Bourgeois JA, Klein M: Risperidone and fluoxetine in the treatment of pedophilia with comorbid dysthymia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996, 16: 257-258. 10.1097/00004714-199606000-00015.

Bruggeman R, van der Linden C, Buitelaar JK, Gericke GS, Hawkridge SM, Temlett JA: Risperidone versus pimozide in Tourette's disorder: a comparative double-blind parallel-group study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62: 50-56.

Bruun RD, Budman CL: Risperidone as a treatment for Tourette's syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996, 57: 29-31.

Buitelaar JK: Open-label treatment with risperidone of 26 psychiatrically-hospitalized children and adolescents with mixed diagnoses and aggressive behavior. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000, 10: 19-26.

Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ, Cohen-Kettenis P, Melman CT: A randomized controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of aggression in hospitalized adolescents with subaverage cognitive abilities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62: 239-248.

Dartnall NA, Holmes JP, Morgan SN, McDougle CJ: Brief report: two-year control of behavioral symptoms with risperidone in two profoundly retarded adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999, 29: 87-91. 10.1023/A:1025926817928.

Demb HB: Risperidone in young children with pervasive developmental disorders and other developmental disabilities. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1996, 6: 79-80.

Doan RJ: Risperidone for insomnia in PDDs. Can J Psychiatry. 1998, 43: 1050-1051.

Dryden-Edwards RC, Reiss AL: Differential response of psychotic and obsessive symptoms to risperidone in an adolescent. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1996, 6: 139-145.

Eidelman I, Seedat S, Stein DJ: Risperidone in the treatment of acute stress disorder in physically traumatized in-patients. Depress Anxiety. 2000, 11: 187-188. 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<187::AID-DA9>3.3.CO;2-3.

Epperson CN, Fasula D, Wasylink S, Price LH, McDougle CJ: Risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant trichotillomania: three cases. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999, 9: 43-49.

Fisman S, Steele M: Use of risperidone in pervasive developmental disorders: a case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1996, 6: 177-190.

Fitzgerald KD, Stewart CM, Tawile V, Rosenberg DR: Risperidone augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment of pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999, 9: 115-123.

Gabriel A: A case of resistant trichotillomania treated with risperidone-augmented fluvoxamine. Can J Psychiatry. 2001, 46: 285-286.

Giakas WJ: Risperidone treatment for a Tourette's disorder patient with comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995, 152: 1097-1098.

Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Silverman P, Schmitz JM, Stotts A, Creson D, Bailey R: Risperidone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: randomized, double-blind trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000, 20: 305-310. 10.1097/00004714-200006000-00003.

Hanna GL, Fluent TE, Fischer DJ: Separation anxiety in children and adolescents treated with risperidone. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999, 9: 277-283.

Hardan A, Johnson K, Johnson C, Hrecznyj B: Case study: risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996, 35: 1551-1556. 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00025.

Hirose S: Effective treatment of aggression and impulsivity in antisocial personality disorder with risperidone. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001, 55: 161-162. 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00805.x.

Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ: Risperidone and explosive aggressive autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1997, 27: 313-323. 10.1023/A:1025854532079.

Jacobsen FM: Risperidone in the treatment of affective illness and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995, 56: 423-429.

Kawahara T, Ueda Y, Mitsuyama Y: A case report of refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder improved by risperidone augmentation of clomipramine treatment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000, 54: 599-601. 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00760.x.

Khouzam HR, Donnelly NJ: Remission of self-mutilation in a patient with borderline personality during risperidone therapy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997, 185: 348-349. 10.1097/00005053-199705000-00011.

Knopf U, Hubrich-Ungureanu P, Thome J: [Paroxetine augmentation with risperidone in therapy-resistant depression]. Psychiatr Prax. 2001, 28: 405-406. 10.1055/s-2001-18610.

Krashin D, Oates EW: Risperidone as an adjunct therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 1999, 164: 605-606.

Lombroso PJ, Scahill L, King RA, Lynch KA, Chappell PB, Peterson BS, McDougle CJ, Leckman JF: Risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with chronic tic disorders: a preliminary report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995, 34: 1147-1152.

Maguire GA, Gottschalk LA, Riley GD, Franklin DL, Bechtel RJ, Ashurst J: Stuttering: neuropsychiatric features measured by content analysis of speech and the effect of risperidone on stuttering severity. Compr Psychiatry. 1999, 40: 308-314.

Masi G, Cosenza A, Mucci M, Brovedani P: Open trial of risperidone in 24 young children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001, 40: 1206-1214. 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00015.

Masi G, Cosenza A, Mucci M, De Vito G: Risperidone monotherapy in preschool children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Neurol. 2001, 16: 395-400.

McDougle CJ, Epperson CN, Pelton GH, Wasylink S, Price LH: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000, 57: 794-801. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.794.

McDougle CJ, Fleischmann RL, Epperson CN, Wasylink S, Leckman JF, Price LH: Risperidone addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: three cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995, 56: 526-528.

McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, Pelton GH, Cohen DJ, Price LH: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998, 55: 633-641. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.633.

Miodownik C, Lerner V: Risperidone in the treatment of psychotic depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2000, 23: 335-337. 10.1097/00002826-200011000-00007.

Monnelly EP, Ciraulo DA: Risperidone effects on irritable aggression in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999, 19: 377-378. 10.1097/00004714-199908000-00016.

Newton TF, Ling W, Kalechstein AD, Uslaner J, Tervo K: Risperidone pre-treatment reduces the euphoric effects of experimentally administered cocaine. Psychiatry Research. 2001, 102: 227-233. 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00255-4.

Nicolson R, Awad G, Sloman L: An open trial of risperidone in young autistic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998, 37: 372-376. 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00014.

O'Connor M, Silver H: Adding risperidone to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor improves chronic depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998, 18: 89-91. 10.1097/00004714-199802000-00018.

Ostroff RB, Nelson JC: Risperidone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999, 60: 256-259.

Perry R, Pataki C, Munoz-Silva DM, Armenteros J, Silva RR: Risperidone in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorder: pilot trial and follow-up. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1997, 7: 167-179.

Pfanner C, Marazziti D, Dell'Osso L, Presta S, Gemignani A, Milanfranchi A, Cassano GB: Risperidone augmentation in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000, 15: 297-301.

Posey DJ, Walsh KH, Wilson GA, McDougle CJ: Risperidone in the treatment of two very young children with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999, 9: 273-276.

Purdon SE, Lit W, Labelle A, Jones BD: Risperidone in the treatment of pervasive developmental disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1994, 39: 400-405.

Raheja RK, Bharwani I, Penetrante AE: Efficacy of risperidone for behavioral disorders in the elderly: a clinical observation. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995, 8: 159-161.

Ravizza L, Barzega G, Bellino S, Bogetto F, Maina G: Therapeutic effect and safety of adjunctive risperidone in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996, 32: 677-682.

Sandor P, Stephens RJ: Risperidone treatment of aggressive behavior in children with Tourette syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000, 20: 710-712. 10.1097/00004714-200012000-00025.

Saxena S, Wang D, Bystritsky A, Baxter L. R., Jr.: Risperidone augmentation of SRI treatment for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996, 57: 303-306.

Schreier HA: Risperidone for young children with mood disorders and aggressive behavior. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1998, 8: 49-59.

Seedat S, Kesler S, Niehaus DJ, Stein DJ: Pathological gambling behaviour: emergence secondary to treatment of Parkinson's disease with dopaminergic agents. Depress Anxiety. 2000, 11: 185-186. 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<185::AID-DA8>3.3.CO;2-8.

Smelson DA, Roy A, Roy M: Risperidone diminishes cue-elicited craving in withdrawn cocaine-dependent patients. Can J Psychiatry. 1997, 42: 984-

Stein DJ, Bouwer C, Hawkridge S, Emsley RA: Risperidone augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997, 58: 119-122.

Stoll AL, Haura G: Tranylcypromine plus risperidone for treatment-refractory major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000, 20: 495-496. 10.1097/00004714-200008000-00020.

Sun TF, Lin PY, Wu CK: Risperidone augmentation of specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: report of two cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2001, 24: 587-592.

Van Bellinghen M, De Troch C: Risperidone in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in children and adolescents with borderline intellectual functioning: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001, 11: 5-13. 10.1089/104454601750143348.

van der Linden C, Bruggeman R, van Woerkom TC: Serotonin-dopamine antagonist and Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome: an open pilot dose-titration study with risperidone. Mov Disord. 1994, 9: 687-688.

Vercellino F, Zanotto E, Ravera G, Veneselli E: Open-label risperidone treatment of 6 children and adolescents with autism. Can J Psychiatry. 2001, 46: 559-560.

Zuddas A, Di Martino A, Muglia P, Cianchetti C: Long-term risperidone for pervasive developmental disorder: efficacy, tolerability, and discontinuation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000, 10: 79-90.

Findling RL, Maxwell K, Wiznitzer M: An open clinical trial of risperidone monotherapy in young children with autistic disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997, 33: 155-159.

Adli M, Rossius W, Bauer M: [Olanzapine in the treatment of depressive disorders with psychotic symptoms]. Nervenarzt. 1999, 70: 68-71. 10.1007/s001150050402.

Ashton AK: Olanzapine augmentation for trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 1929-1930. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1929-a.

Benazzi F: Fluoxetine and Olanzapine for Resistant Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002, 159: 155-10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.155.

Bhadrinath BR: Olanzapine in Tourette syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1998, 172: 366-

Bogetto F, Bellino S, Vaschetto P, Ziero S: Olanzapine augmentation of fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): a 12-week open trial. Psychiatry Res. 2000, 96: 91-98. 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00203-1.

Budman CL, Gayer A, Lesser M, Shi Q, Bruun RD: An open-label study of the treatment efficacy of olanzapine for Tourette's disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62: 290-294.

Butterfield MI, Becker ME, Connor KM, Sutherland S, Churchill LE, Davidson JR: Olanzapine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001, 16: 197-203. 10.1097/00004850-200107000-00003.

Francobandiera G: Olanzapine augmentation of serotonin uptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open study. Can J Psychiatry. 2001, 46: 356-358.

Garnis-Jones S, Collins S, Rosenthal D: Treatment of self-mutilation with olanzapine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000, 4: 161-163.

Ghaemi SN, Cherry EL, Katzow JA, Goodwin FK: Does olanzapine have antidepressant properties? A retrospective preliminary study. Bipolar Disord. 2000, 2: 196-199. 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020109.x.

Grant JE: Successful treatment of nondelusional body dysmorphic disorder with olanzapine: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62: 297-298.

Gupta MA, Gupta AK: Olanzapine is effective in the management of some self-induced dermatoses: three case reports. Cutis. 2000, 66: 143-146.

Gupta MA, Gupta AK: Olanzapine may be an effective adjunctive therapy in the management of acne excoriee: a case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001, 5: 25-27.

Hansen L: Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry. 1999, 175: 592-

Hough DW: Low-dose olanzapine for self-mutilation behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62: 296-297.

Jensen VS, Mejlhede A: Anorexia nervosa: treatment with olanzapine. Br J Psychiatry. 2000, 177: 87-10.1192/bjp.177.1.87.

Konig F, von Hippel C, Petersdorff T, Neuhoffer-Weiss M, Wolfersdorf M, Kaschka WP: First experiences in combination therapy using olanzapine with SSRIs (citalopram, paroxetine) in delusional depression. Neuropsychobiology. 2001, 43: 170-174. 10.1159/000054886.

Koran LM, Ringold AL, Elliott MA: Olanzapine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000, 61: 514-517.

Krishnamoorthy J, King BH: Open-label olanzapine treatment in five preadolescent children. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1998, 8: 107-113.

La Via MC, Gray N, Kaye WH: Case reports of olanzapine treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000, 27: 363-366. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200004)27:3<363::AID-EAT16>3.3.CO;2-X.

Labbate LA, Douglas S: Olanzapine for nightmares and sleep disturbance in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Can J Psychiatry. 2000, 45: 667-668.

Malek-Ahmadi P, Simonds JF: Olanzapine for autistic disorder with hyperactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998, 37: 902-10.1097/00004583-199809000-00006.

Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, Choudhury MS, Delaney MA: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001, 40: 887-894. 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00009.

Nelson LA, Swartz CM: Melancholic symptoms during concurrent olanzapine and fluoxetine. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000, 12: 167-170. 10.1023/A:1009021119654.

Onofrj M, Paci C, D'Andreamatteo G, Toma L: Olanzapine in severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a 52-week double-blind cross-over study vs. low-dose pimozide. J Neurol. 2000, 247: 443-446. 10.1007/s004150070173.

Petty F, Brannan S, Casada J, Davis LL, Gajewski V, Kramer GL, Stone RC, Teten AL, Worchel J, Young KA: Olanzapine treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: an open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001, 16: 331-337. 10.1097/00004850-200111000-00003.

Pitchot W, Ansseau M: Addition of olanzapine for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 1737-1738. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1737-a.

Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, McDougle CJ: Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: an open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999, 19: 37-44. 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00008.

Potenza MN, Wasylink S, Epperson CN, McDougle CJ: Olanzapine augmentation of fluoxetine in the treatment of trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 1998, 155: 1299-1300.

Rothschild AJ, Bates KS, Boehringer KL, Syed A: Olanzapine response in psychotic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999, 60: 116-118.

Schulz SC, Camlin KL, Berry SA, Jesberger JA: Olanzapine safety and efficacy in patients with borderline personality disorder and comorbid dysthymia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999, 46: 1429-1435. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00128-6.

Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, Stahl S, Gannon KS, Jacobs TG, Buras WR, Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Spencer KA, Feldman PD, Meltzer HY: A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 131-134. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.131.

Soler J, Campins MJ, Perez V, Puigdemont D, Perez-Blanco E, Alvarez E: [Olanzapine and cognitive-behavioural group therapy in borderline personality disorder]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2001, 29: 85-90.

Squitieri F, Cannella M, Piorcellini A, Brusa L, Simonelli M, Ruggieri S: Short-term effects of olanzapine in Huntington disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2001, 14: 69-72.

Stamenkovic M, Schindler SD, Aschauer HN, De Zwaan M, Willinger U, Resinger E, Kasper S: Effective open-label treatment of tourette's disorder with olanzapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000, 15: 23-28.

Weisler RH, Ahearn EP, Davidson JR, Wallace CD: Adjunctive use of olanzapine in mood disorders: five case reports. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1997, 9: 259-262. 10.1023/A:1022312612221.

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR: Olanzapine treatment of female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001, 62: 849-854.

Khullar A, Chue P, Tibbo P: Quetiapine and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS): case report and review of atypical antipsychotic-induced OCS. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001, 26: 55-59.

Martin A, Koenig K, Scahill L, Bregman J: Open-label quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999, 9: 99-107.

Padla D: Quetiapine resolves psychotic depression in an adolescent boy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001, 11: 207-208. 10.1089/104454601750284153.

Parraga HC, Parraga MI, Woodward RL, Fenning PA: Quetiapine treatment of children with Tourette's syndrome: report of two cases. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001, 11: 187-191. 10.1089/104454601750284108.

APA: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, 4th Edition. 1994, Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press

Shapiro E, Shapiro AK,, Fulop G: Controlled study of haloperidol, pimozide and placebo for the treatment of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989, 46: 722-730.

Caine ED, Polinsky RJ, Kartzinel R: The trial use of clozapine for abnormal involuntary movement disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979, 317-320.

Anderson LT, Cambell M, Grega DM, Perry R, Small AM, Green WH: Haloperidol in the treatment of infantile autism: effects on learning and behavioral symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984, 141: 1195-1202.

Gordon CT, Rapoport JL, Hamburger SD, State RC, Mannheim GB: Differential response of seven subjects with autistic disorder to clomipramine and desipramine. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992, 149: 363-366.

Gordon CT, State RC, Nelson JE, Hamburger SD, Rapoport JL: A double-blind comparison of clomipramine, desipramine and placebo in the treatment of autistic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993, 50: 441-447.

McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, FV Volkmar, Heninger GR, LH Price: A double-blind placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996, 53: 1001-1008.

Meert TF, PAJ Janssen: Ritanserin: a new therapeutic approach for drug abuse. Part 2: effects on cocaine. Drug Development Research. 1992, 39-53.

Schotte A, Janssen PMF, Gommeren W, Luyten WHML, VanGompel P, Lesage AS, DeLoore K, Leysen J: Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding. Psychopharmacology (Berlin). 1996, 57-73.

McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Price LH, Delgado PL, Krystal JH, Charney DS, Heninger GR: Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obssessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990, 302-308.

Zhang W, Perry WK, Wong DT, Potts BD, Bao J, Tollefson GD, Bymaster FP: Synergistic effects of olanzapine and other antipsychotic agents in combination with fluoxetine on neorepinephrine and dopamine release in rat prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000, 250-262. 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00119-6.

Leone NF: Response of borderline patients to loxapine and chlorpromazine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1982, 148-150.

Soloff PH, George A, Nathan RS: Amitriptyline versus haloperidol in borderlines: final outcome and predictors of response. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1989, 238-246.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Fountoulakis, K.N., Nimatoudis, I., Iacovides, A. et al. Off-label indications for atypical antipsychotics: A systematic review. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 3, 4 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2832-3-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2832-3-4