Abstract

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are a high risk population for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Our study aims to find whether MSM who were recruited online had a higher prevalence of self-reported unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) than those who were recruited offline.

Methods

A meta-analysis was conducted from the results of published studies. The analysis was stratified by the participants’ geographic location, the sample size and the date of the last reported UAI.

Results

Based on fourteen studies, MSM who were recruited online (online-based group) reported that 33.9% (5,961/17,580) of them had UAI versus 24.9% (2,700/10,853) of MSM who were recruited offline (offline-based group). The results showed that it is more likely for an online-based MSM group to have UAI with male partners than an offline-based MSM group [odds ratio (OR) = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.13-1.62, P < 0.01]. The subgroup analysis results also showed that the prevalence of UAI was higher in the European subsample (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.17-1.63, P < 0.01) and in sample sizes of more than 500 individuals (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.09-1.61, P < 0.01) in the online group compared to the offline group. The prevalence of UAI was also significantly higher when the time of the last UAI was during the last 3 or more months (OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.13-1.74, P < 0.05) in the online group compared to the offline group. A sensitivity analysis was used to test the reliability of the results, and it reported that the results remained unchanged and had the same estimates after deleting any one of the included studies.

Conclusions

A substantial percentage of MSM were recruited online, and they were more inclined to engage in UAI than MSM who were recruited offline. Targeted interventions of HIV prevention programs or services are recommended when designing preventive interventions to be delivered via the Internet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Currently, the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among men who have sex with men (MSM) is rapidly increasing worldwide [1–4]. MSM are also at a high risk of infection with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) [5, 6] because of related risky behaviors, such as having multiple partners and engaging in unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) [7]. Many studies showed that MSM seeking male sexual partners (sampled offline or from fixed venues, such as gay bars, bathrooms, or clubs) engage in several risky sexual behaviors, such as UAI, having multiple sex partners and anal sex [8–12]. However, the studies are limited because offline sampling misses MSM who do not go to these venues due to fear of discrimination, and some HIV-positive MSM who are at high risk for transmission of HIV or STDs may not go to these places either.

The recruitment of MSM for studies is a challenge for researchers because no sampling frame exists for MSM and public acknowledgement of membership may also be stigmatized in some cases [13]. The Internet, with its convenience of accessibility to communication, information, entertainment and web-based communities [14], has become a basic tool for MSM who seek sex partners and for arranging liaisons [15]. MSM can find sexual partners through chat rooms or the corresponding social forums online (eg. http://www.gaydar.net/); they also perceive that this method is convenient and cost-effective because it is private, anonymous, safe and convenient in the process of communication. Although many studies have applied offline-based sampling to MSM [16–19], several studies [20–22] sampling MSM who seek male sexual partners via the Internet have shown that such online-based sampling is cost-effective and has lots of advantages.

Some studies have shown that online-based MSM were more likely to report different socio-demographic profiles [1] and risky sexual behaviors, such as self-identified sexual orientation [1, 7], UAI [1, 23, 24] and having multiple sex partners [24, 25], compared with offline-based MSM. The online-based sample was significantly younger (Internet sample mean age 33.2 years old, offline 37.6 years old) and was comprised of more bisexual men (Internet sample 20%, offline 5%) than the offline MSM sample [26]. In addition, epidemiological studies performed in European [27, 28], American [29] and Asian [1, 7] MSMs reported risky sexual behavior (e.g., UAI, having multiple sex partners) and showed an increase in the prevalence of UAI.

It is important to examine the validity of sampling online compared to more established venue-based methods because the individuals recruited by sampling online may be fundamentally different from those recruited offline, with respect to their sexual risks. In the past few decades, several studies [26, 28–31] have reported that online-based MSM were more likely to have UAI with male sex partners than offline-based MSM, but the findings are inconsistent and show some conflicting outcomes due to different regions or low statistical power. In our research, we conducted a meta-analysis to assess whether online-based MSM had a higher self-reported UAI prevalence than offline-based MSM.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Studies published before December 2013 that examined the prevalence of UAI among MSM were carefully selected from the following databases: PubMed (1966 to 2013), Springer (1996 to 2013), Cochrane Library (1993 to 2013), Google Scholar (1987 to 2013), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, 1979 to 2013) and the Wanfang database (Chinese, 1990 to 2013). The date of the last search was February 8, 2014. The databases were searched using the following key words: “men who have sex with men”, “Internet”, “web”, “online”, “offline”, “venue”, “MSM”, “gay”, “homosexuality”, “risky behavior”, “sexual behavior” or “anal intercourse”. No language restrictions were carried out for this study. All of the studies that investigated the prevalence of UAI among online-based MSM or offline-based MSM were evaluated carefully. The selection criteria are listed as follows: (1) the reports were full-length, published papers; (2) the studies reported data for UAI among MSM, and the duration of UAI was not limited; and (3) all of the studies recruited MSM both online and offline. We excluded the studies in which the reported UAI data were from MSM recruited either only online or offline and any meeting or conference abstract data.

Search methods

Two investigators (Yang ZR and Zhang SC) reviewed the abstracts independently to determine whether the studies conformed to the eligibility criteria for this study. Two other investigators (Jin MH and Dong ZQ) reviewed the references in the papers to identify any additional studies. A third investigator (Han JK) carried out additional assessments if discrepancies were generated. In our study, there were no discrepancies.

Data extraction

The data items included study details (e.g., sample size, year of publication, location of participants), characteristics of participants (e.g., age, proportion of MSM), and different risky sexual behaviors (e.g., never used a condom in the process of anal intercourse with partners in the last year, inconsistent condom use during anal intercourse in the last year, UAI with a male partner in the past three months, etc.). Two investigators (Yang ZR and Dong ZQ) extracted the data independently using the standardized protocol by coding forms, and a third investigator (Jin MH) reviewed the results.

For each study, we recorded the first author’s name, the publication year, the country and geographic location, the definition of UAI (risky sexual behaviors, such as UAI in the last x months, UAI with a casual partner, etc.), the sample size and the prevalence of UAI. UAI was defined as having never used a condom during anal sex in the last year, using condoms inconsistently in the process of anal intercourse in the last year, UAI with a serodiscordant or HIV-unknown male partner, UAI with a male partner in the last three months, UAI in the last two months, UAI with any male partner in the last three months, UAI with a casual partner in the last six months, UAI in the last three months, UAI with a male partner in the last incident of anal sex, any UAI with any partner, or being engaged in any MSM UAI in the last year.

Meta-analysis methods

This study assessed the comparison of the UAI prevalence between MSM who were recruited online (online-based group) vs. those who were recruited offline (offline-based group). The online-based group’s participants were investigated through the Internet (online), and the respondents of the offline-based group were surveyed in bathhouses, bars, clubs, etc. We examined the association with the prevalence of UAI among MSM between the online-based group and the offline-based group. Then, we merged data from the same geographic location, sample size and the last incidence of UAI by means of subgroup analysis.

The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated with respect to each study. We quantified the effect of heterogeneity by means of the formula I 2 = 100% × (Q − df)/Q [32]. We also estimated the within-study and between-study variation or heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q-statistic [33]. The random effect model was then used for the meta-analysis if a significant Q-statistic (P < 0.10) existed; otherwise, the fixed effect model was used [34].

The overall OR, or the pooled estimate of risk, was obtained using the Mantel-Haenszel method in the fixed effect model [35] and using the DerSimonian and Laid method in the random effect model [36]. The pooled OR in the meta-analysis was calculated by weighting the individual ORs using the inverse of their variance [34]. The significance of the pooled OR was determined using a Z-test [37]. To test the reliability of the results, we also performed a sensitivity analysis after deleting any one of the included studies.

Evaluation of publication bias

We measured the asymmetry of the funnel plot by using Egger’s linear regression [38], which assessed funnel plot asymmetry using the natural logarithm scale of the OR [34]. The intercept α provides a measure of asymmetry: the larger its deviation from zero, the more pronounced the asymmetry [38].

The meta-analysis was conducted with Review Manager 5.1 software (Cochrane Collaboration, http://tech.cochrane.org/revman) and the STATA software package v.11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). All the P values were two-sided. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

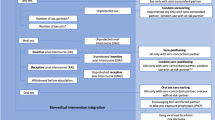

There were 1515 reports or literature pieces related to the search terms (PubMed: 569; Springer: 149; Cochrane Library: 8; Google Scholar: 268; CNKI: 321; Wanfang: 200). The flow chart of study enrollment for this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1. A total of 317 studies were potentially relevant after duplicate or unrelated studies were excluded. During the abstract screening procedure, 249 papers were removed (56 were review articles; 125 had no data on UAI; 68 did not include MSM). A total of 68 articles were retained for full text review, and 54 papers (23 due to reporting UAI data from MSM recruited either only online or offline; 31 due to unavailability of data) were removed after full text review.

A total of 14 studies published between 2000 and 2012 were included in this meta-analysis. The characteristics of the selected studies are listed in Table 1. There were 28,433 participants (online group 17,580; offline group 10,853) in this meta-analysis. Six of the studies were carried out in Europe [23, 26–28, 30, 31], three in Asia [1, 7, 39] and five in America [29, 40–43]. The prevalence of UAI varied between 9.8% and 59.9% in the online-based group and between 7.5% and 64.9% in the offline-based group. We merged the research data according to the same geographic location, sample size and time of last UAI; we also analyzed these subgroups independently.

Overall results of the meta-analysis on the UAI prevalence

The summary of the prevalence of UAI among MSM is shown in Table 1. The results of the fourteen separate studies indicated that 33.9% (5,961/17,580) of MSM in the online group had UAI compared to 24.9% (2,700/10,853) of MSM in the offline group. As shown in Table 2, we found that the prevalence of UAI among online-based MSM was higher than the offline-based group in the overall analysis. The pooled OR was 1.35 (95% CI = 1.13-1.62, P < 0.01) for UAI between the online-based group and the offline-based group using the random effect model because between-study heterogeneity was significant (Q = 93.06, P < 0.001, I 2 = 86.0%).

Subgroup meta-analysis for UAI prevalence

We performed subgroup analyses stratified by the participants’ geographic location, the sample size and the time of last UAI in this study (Table 2). The subgroup analysis results showed that the prevalence of UAI was higher in the European subsample (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.17-1.63, P < 0.01) and in sample sizes of more than 500 individuals (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.09-1.61, P < 0.01) in the online group compared to the offline group. The prevalence of UAI was also significantly higher when the time of the last UAI was during the last 3 or more months (OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.13-1.74, P < 0.05) in the online group compared to the offline group.

Sensitivity analysis

The effect of any single research study on the overall meta-analysis was carried out by deleting one study at a time. The exclusion of any individual study did not make a significant difference to this meta-analysis, suggesting that the results of our study are statistically reliable.

Evaluation of publication bias

The Egger’s linear regression test was evaluated for funnel plot asymmetry (Table 3). The results showed that no publication bias existed in the overall analysis or the subgroup analysis.

Discussion

We extracted fourteen studies that included 17,580 MSM who were recruited online (online group) and 10,853 MSM who were recruited offline (offline group) to evaluate the prevalence of UAI among MSM in this study. Our meta-analysis suggested that there was a higher prevalence of UAI among MSM who were recruited online than those recruited offline. The prevalence of UAI was defined differently in the fourteen studies of this meta-analysis, with the prevalence varying between 9.8% and 59.9% among MSM who were recruited online and between 7.5% and 64.9% among those who were recruited offline. These results suggest that the populations under study and the evaluation of risk groups vary in different, we should lead to caution when interpretating differences based on the mode of recruitment.

We performed subgroup analyses stratified by the participants’ geographic location (Europe, America and Asia), sample size (groups of more than 500 and less than or equal to 500 individuals) and the time of last UAI (UAI in the last six or more months and UAI in the last three or less months) to decrease the differences based on the mode of recruitment. The subgroup analyses showed that MSM who were recruited online were associated with increased UAI in studies with a sample size of more than 500 individuals but not in studies with a cohort of less than or equal to 500; this may have been due to reduced sampling bias in studies with larger samples. In addition, a high rate of UAI is primarily due to the definition or scope of UAI; therefore, if the definition or scope of UAI is broader (a broader definition of UAI means that the scope of UAI is unlimited or less limited), the UAI rate would be accordingly higher. Recently, a meta-analysis [15] demonstrated that online-based MSM were more likely to have UAI with male sex partners than offline-based MSM. That study provided the hypothesis for this meta-analysis and the results of that study [15] are consistent with our results, but that study did not perform subgroup analyses, such as subsample-based analyses, sample size-based analyses and last UAI time-based analyses.

Some limitations of this study should be discussed as well. First, only published studies were included in the present meta-analysis [44]. Thus, publication bias of our research may be possible; however, this was not observed in the statistical test. Second, this study assumes that the sample of MSM recruited online is representative of those MSM who met sexual partners online, and it also assumes that the sample of MSM recruited offline is representative of those MSM who met sexual partners at gay venues. Therefore, this study may have a generalization bias. In addition, statistically significance between-study heterogeneity was detected in the current study and may be distorting the results of this meta-analysis [45]. For example, men who were recruited through social networking sites, such as Facebook, are likely to be behaviorally very different from men who were recruited through sex-seeking sites, such as ManHunt. However, this was not a major problem because the self-reported risky sexual behavior involving UAI by MSM recruited online or offline was heterogeneous. Different subsamples may also contribute to the heterogeneity; therefore, the results of our meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution because the subsamples from the six countries used in this study were not uniform.

Our study found that MSM who were recruited online are more likely to engage in UAI with male partners than offline-based MSM, so data obtained from MSM using convenient Internet networks can provide potentially powerful tools for informing public health interventions. Most of the previous studies were conducted using offline-recruited (venue-based) sampling methods among MSM. Researchers used the results of those studies to design intervention measures targeting ordinary MSM, and these measures may not be suitable for online-based MSM who seek sexual partners [1]. The Internet provides researchers with valuable opportunities for conducting behavioral surveys among MSM because some MSM who are at a high risk of STDs or HIV infection may not participate in research when the investigation is conducted in the gay-specific venues [28]. The reasons why online MSM may be engaging in more UAI compared with offline MSM are as follows, those online-based MSM are less likely to be tested for HIV and more likely to have UAI with partners compared with offline-based MSM [46], and online-based HIV-negative MSM are more inclined to have UAI with potentially serodiscordant partners than offline-based MSM as well [47]. The risk of HIV infection should decrease after both an increased rate of condom use and standardized STD treatment for MSM [48]. There are valuable interventions for AIDS/STD prevention and treatment among MSM through the Internet, including promoting the use of condoms and encouraging the treatment of STDs.

Specific Internet related interventions may be helpful for online-based MSM, and it is crucial for HIV/STD control and prevention staff to pay more attention to this population to increase the awareness of self-protection and decrease the risk of HIV/STDs among online-based MSM.

Conclusions

Increased sexual risk behavior has been linked to MSM who seek their partners online. This new situation will have extremely important implications for worldwide HIV/AIDS prevention, and increased attention should be paid to MSM because of this association. This study supports the results that a substantial percentage of MSM who were recruited online are more likely to engage in UAI than MSM who were recruited offline. Because we only used published papers in this study, we also need to pay close attention to the influences of unpublished studies, such as dissertations and papers presented at various conferences, which may help to confirm the results of this study. Targeted interventions of HIV prevention programs or services are recommended when designing preventive interventions to be delivered through the Internet.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- UAI:

-

Unprotected anal intercourse

- STD:

-

Sexually transmitted diseases

- CNKI:

-

China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

References

Tsui HY, Lau JT: Comparison of risk behaviors and socio-cultural profile of men who have sex with men survey respondents recruited via venues and the internet. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 232-10.1186/1471-2458-10-232.

Mitsch A, Hu X, Harrison KMD, Durant T: Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among men who have sex with men–33 states, 2001–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008, 57: 681-686.

Macdonald N, Dougan S, McGarrigle CA, Baster K, Rice BD, Evans BG, Fenton KA: Recent trends in diagnoses of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in England and Wales among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2004, 80: 492-497. 10.1136/sti.2004.011197.

Ma X, Zhang Q, He X, Sun W, Yue H, Chen S, Raymond HF, Li Y, Xu M, Du H, McFarland W: Trends in prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Results of 3 consecutive respondent-driven sampling surveys in Beijing, 2004 through 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 45: 581-587. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811eadbc.

Torian LV, Makki HA, Menzies IB, Murrill CS, Weisfuse IB: HIV infection in men who have sex with men, New York City Department of Health sexually transmitted disease clinics, 1990-1999: a decade of serosurveillance finds that racial disparities and associations between HIV and gonorrhea persist. Sex Transm Dis. 2002, 29: 73-78. 10.1097/00007435-200202000-00002.

Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Bright D, Cranston K, Isenberg D, Bland S, Barker TA, Mayer KH: Clinically significant depressive symptoms as a risk factor for HIV infection among black MSM in Massachusetts. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13: 798-810. 10.1007/s10461-009-9571-9.

Xing JM, Zhang KL, Chen X, Zheng J: A cross-sectional study among men who have sex with men: a comparison of online and offline samples in Hunan Province, China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2008, 121: 2342-2345.

Katz MH, McFarland W, Guillin V, Fenstersheib M, Shaw M, Kellogg T, Lemp GF, MacKellar D, Valleroy LA: Continuing high prevalence of HIV and risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men: the young men’s survey in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1992 to 1993 and in 1994 to 1995. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998, 19: 178-181. 10.1097/00042560-199810010-00012.

O’Donnell L, Agronick G, San DA, Duran R, Myint-U A, Stueve A: Ethnic and gay community attachments and sexual risk behaviors among urban Latino young men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002, 14: 457-471. 10.1521/aeap.14.8.457.24109.

Crosby R, Holtgrave DR, Stall R, Peterson JL, Shouse L: Differences in HIV risk behaviors among black and white men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007, 34: 744-748.

Akin M, Fernandez MI, Bowen GS, Warren JC: HIV risk behaviors of Latin American and Caribbean men who have sex with men in Miami, Florida, USA. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2008, 23: 341-348. 10.1590/S1020-49892008000500006.

Velter A, Barin F, Bouyssou A, Guinard J, Leon L, Le Vu S, Pillonel J, Spire B, Semaille C: HIV prevalence and sexual risk behaviors associated with awareness of HIV status among men who have sex with men in Paris, France. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17: 1266-1278. 10.1007/s10461-012-0303-1.

Carballo-Dieguez A, Balan I, Marone R, Dolezal C, Barreda V, Leu CS, Avila MM: Use of respondent driven sampling (RDS) generates a very diverse sample of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e27447-10.1371/journal.pone.0027447.

Kubicek K, Carpineto J, McDavitt B, Weiss G, Kipke MD: Use and perceptions of the internet for sexual information and partners: a study of young men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2011, 40: 803-816. 10.1007/s10508-010-9666-4.

Liau A, Millett G, Marks G: Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006, 33: 576-584. 10.1097/01.olq.0000204710.35332.c5.

Li SW, Zhang XY, Li XX, Wang MJ, Li DL, Ruan YH, Zhang XX, Shao YM: Detection of recent HIV-1 infections among men who have sex with men in Beijing during 2005–2006. Chin Med J (Engl). 2008, 121: 1105-1108.

Forrest DW, Metsch LR, LaLota M, Cardenas G, Beck DW, Jeanty Y: Crystal methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive and HIV-negative men who have sex with men in South Florida. J Urban Health. 2010, 87: 480-485. 10.1007/s11524-009-9422-z.

Magnus M, Kuo I, Phillips G, Shelley K, Rawls A, Montanez L, Peterson J, West-Ojo T, Hader S, Greenberg AE: Elevated HIV prevalence despite lower rates of sexual risk behaviors among black men in the District of Columbia who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010, 24: 615-622. 10.1089/apc.2010.0111.

Jenness SM, Neaigus A, Murrill CS, Gelpi-Acosta C, Wendel T, Hagan H: Recruitment-adjusted estimates of HIV prevalence and risk among men who have sex with men: effects of weighting venue-based sampling data. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126: 635-642.

Jakopanec I, Schimmer B, Grjibovski AM, Klouman E, Aavitsland P: Self-reported sexually transmitted infections and their correlates among men who have sex with men in Norway: an Internet-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2010, 10: 261-10.1186/1471-2334-10-261.

Mimiaga MJ, Tetu AM, Gortmaker S, Koenen KC, Fair AD, Novak DS, Vanderwarker R, Bertrand T, Adelson S, Mayer KH: HIV and STD status among MSM and attitudes about Internet partner notification for STD exposure. Sex Transm Dis. 2008, 35: 111-116. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181573d84.

Zhang D, Bi P, Lv F, Tang H, Zhang J, Hiller JE: Internet use and risk behaviours: an online survey of visitors to three gay websites in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2007, 83: 571-576. 10.1136/sti.2007.026138.

Evans AR, Wiggins RD, Mercer CH, Bolding GJ, Elford J: Men who have sex with men in Great Britain: comparison of a self-selected internet sample with a national probability sample. Sex Transm Infect. 2007, 83: 200-205. discussion 205

Benotsch EG, Kalichman S, Cage M: Men who have met sex partners via the Internet: prevalence, predictors, and implications for HIV prevention. Arch Sex Behav. 2002, 31: 177-183. 10.1023/A:1014739203657.

Horvath KJ, Rosser BR, Remafedi G: Sexual risk taking among young internet-using men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98: 1059-1067. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111070.

Hospers HJ, Kok G, Harterink P, De Zwart O: A new meeting place: chatting on the Internet, e-dating and sexual risk behaviour among Dutch men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2005, 19: 1097-1101. 10.1097/01.aids.0000174457.08992.62.

Fernández-Dávila P, Zaragoza LK: Internet and sexual risk in men who have sex with men. Gac Sanit. 2009, 23: 380-387. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2008.11.004.

Elford J, Bolding G, Davis M, Sherr L, Hart G: Web-based behavioral surveillance among men who have sex with men: a comparison of online and offline samples in London, UK. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004, 35: 421-426. 10.1097/00126334-200404010-00012.

Knapp WD, Seeley S, St LJS: A comparison of Web- with paper-based surveys of gay and bisexual men who vacationed in a gay resort community. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004, 16: 476-485. 10.1521/aeap.16.5.476.48735.

Ross MW, Tikkanen R, Mansson SA: Differences between Internet samples and conventional samples of men who have sex with men: implications for research and HIV interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2000, 51: 749-758. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00493-1.

Bolding G, Davis M, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J: Gay men who look for sex on the Internet: is there more HIV/STI risk with online partners. AIDS. 2005, 19: 961-968. 10.1097/01.aids.0000171411.84231.f6.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003, 327: 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ: Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. BMJ Books. 2005, 285-312. [Part IV: Statistical methods and computer software.]

Fan Y, Li LH, Pan HF, Tao JH, Sun ZQ, Ye DQ: Association of ITGAM polymorphism with systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011, 25: 271-275. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03776.x.

Mantel N, Haenszel W: Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959, 22: 719-748.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Munafo MR, Bowes L, Clark TG, Flint J: Lack of association of the COMT (Val158/108 Met) gene and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2005, 10: 765-770. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001664.

Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315: 629-634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Liu KL, Gao Y, Wu ZY: Study on the feasibility of using Internet to survey men who have sex with men. Chin J Epidemiol (in chinese). 2011, 32: 207-208.

Rhodes SD, DiClemente RJ, Cecil H, Hergenrather KC, Yee LJ: Risk among men who have sex with men in the United States: a comparison of an Internet sample and a conventional outreach sample. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002, 14: 41-50. 10.1521/aeap.14.1.41.24334.

Raymond HF, Rebchook G, Curotto A, Vaudrey J, Amsden M, Levine D, McFarland W: Comparing internet-based and venue-based methods to sample MSM in the San Francisco Bay Area. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14: 218-224. 10.1007/s10461-009-9521-6.

Grov C: HIV risk and substance use in men who have sex with men surveyed in bathhouses, bars/clubs, and on Craigslist.org: venue of recruitment matters. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16: 807-817. 10.1007/s10461-011-9999-6.

Sanchez T, Smith A, Denson D, Dinenno E, Lansky A: Internet-based methods may reach higher-risk men who have sex with men not reached through venue-based sampling. Open AIDS J. 2012, 6: 83-89. 10.2174/1874613601206010083.

Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Buter J, Berkhof J, Slotman BJ: The additional value of chemotherapy to radiotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 4604-4612. 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.074.

Lee YH, Rho YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG, Nath SK, Harley JB: The PTPN22 C1858T functional polymorphism and autoimmune diseases–a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007, 46: 49-56. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel170.

Tikkanen R, Ross MW: Looking for sexual compatibility: experiences among Swedish men in visiting Internet gay chat rooms. CyberPsychology Behav. 2004, 3: 605-616.

Berry M, Raymond HF, Kellogg T, McFarland W: The Internet, HIV serosorting and transmission risk among men who have sex with men, San Francisco. AIDS. 2008, 22: 787-789. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f55559.

Ma N, Zheng M, Liu M, Chen X, Zheng J, Chen HG, Wang N: Impact of condom use and standardized sexually transmitted disease treatment on HIV prevention among men who have sex with men in hunan province: using the Asian epidemic model. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012, 28: 1273-1279. 10.1089/aid.2011.0294.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/508/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank everyone for their valuable contributions to this article. The study is funded by the science and technology plan projects of Huzhou city.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JM, HJ and DZ participated in the design of the study and data collection. YZ performed the statistical analysis. YZ and ZS conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Zhongrong Yang, Sichao Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Zhang, S., Dong, Z. et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse in men who have sex with men recruited online versus offline: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 14, 508 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-508

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-508