Abstract

Background

Raised blood pressure (BP) is associated with the incidence of metabolic syndrome (MetS). It is unknown if subjects with different BP levels may develop certain components of MetS over time. We investigated the incidence of MetS relative to different levels of BP over a 5-year period in a Chinese population in Tongren Hospital, Beijing.

Methods

During the period of 2006–2011, we recruited 2,781 participants with no MetS, or self-reported type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease at baseline. Association rule was used to identify the transitions of MetS components over time.

Results

The incidence of MetS at follow-up was 9.74% for men and 3.21% for women in the group with optimal BP; 10.29% and 7.22%, respectively, in the group with normal BP; 10.49% and 10.84%, respectively, in the group with high-normal BP; and 14.48% and 23.21%, respectively in the group with high BP. The most common transition was from healthy to healthy in the groups with optimal or normal BP (17.9–49.3%), whereas in the high-normal BP group, 16.9-22.1% of subjects with raised BP returned to healthy status or stayed unchanged, while 13.8-21.4% of people with high BP tended to develop raised fasting glucose levels.

Conclusions

The incidence of MetS increased in parallel with the increase in BP. People with optimal and normal BP levels were less susceptible to developing MetS over time, whereas abnormal BP seemed to be a pre-existing phase of MetS. High-normal BP was a crucial status for MetS prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a complex medical condition comprising five inter-related risk factors within an individual: obesity, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and hyperglycemia [1, 2]. It is a growing public-health issue and with approximately one quarter of the world adult population having the disorder [3]. Several studies have indicated that insulin resistance is a major underlying cause of MetS [4–6]. And MetS is frequently reported to be in association with cardiovascular disease (CVD) [7–10]. But the clinical value of MetS and its effect on a patient life is still controversial [11, 12]. As a result, there is an absence of conclusive recommendations for patients with MetS [13].

Hypertension may trigger the pathogenesis of CVD, and has been shown to be a key factor of MetS [14]. The Framingham Heart Study showed that hypertension played a central role in MetS, and was the most commonly associated risk factor for MetS [15]. Subjects with certain combinations of MetS components showed greater arterial changes, and MetS might be a consequence of raised blood pressure (BP). Thus, MetS predicts the onset of CVD, as it has deleterious effects associated with central arterial aging [16, 17].

Although these results may provide clues as to which risk factors underlie the pathophysiology of MetS, there have been few studies investigating which MetS components tend to cluster dominantly, and how the state of each risk factor changes over time [15, 18].

In the present study, we classified subjects with different levels of BP into four groups at baseline in order to investigate: 1) whether there is a correlation between the level of BP and the incidence of MetS; 2) what risk factors tend to develop at each level of BP; and 3) how these risk factors change with time.

Methods

Survey methodology and laboratory tests

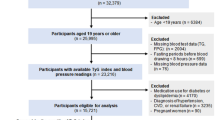

At Beijing Tongren Hospital, subjects’ health records of routine physical check-ups have been computerized since 2006. We selected the records of adult visitors who had a physical check-up, using in 2006/2007 as the baseline, and 2010/2011 as the end point. Totally, there were 7,512 people who had check-up records both at baseline and the follow-up. 3,406 subjects with missing data of weight, height, systolic or diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP), fasting blood glucose (FPG), triglycerides(TG), or HDL-C were excluded. 950 subjects with any medical history of stroke, heart failure, angina pectoris or myocardial infarction, or in use of any hypoglycemic, anti-dislipidemic, or antihypertensive treatment were excluded as well. 975 subjects who had MetS at baseline were ruled out. The final cohort was composed of 2,781 participants.

The physical check-ups included measurements of weight, height, and BP, and analyses of blood biochemistry parameters. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Patients were given a five-minute rest in a seated position before systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP) were measured with a mercury sphygmomanometer.

The blood biochemical analyses included FPG and HDL-C. The blood samples were taken from the cubital vein in the morning after 8 o’clock. Each individual confirmed that there had been no food intake for least 10 hours. The samples were analyzed immediately after pre-treatment or stored at -80°C for further analysis. Serum HDL-C concentration was measured photometrically (Hitachi 704; Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and TG and FPG concentrations were determined enzymatically (Hitachi 717; Roche Diagnostics), with all analyses performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Definition of metabolic syndrome

Diagnostic criteria for the assessment of MetS components were defined according to the Joint Scientific Statement of MetS [19]. However, as waist circumference was not obtained, BMI was taken as a substitute for the component of obesity, as it was reported previously that BMI was strongly associated hypertension and CVD in a population of northern Chinese [20]. The diagnosis criteria used in our research were as follows:

-

Overweight: BMI ≥ 25 and < 30 kg/m2; obese: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2[21];

-

Raised TG level (drug treatment for raised triglyceride level is an alternative indicator): ≥ 150 mg/dl (1.7 mmol/L) [19];

-

Reduced HDL-C level (drug treatment for reduced HDL-C level is an alternative indicator): < 40 mg/dl (1.0 mmol/L) in male; < 50 mg/dl (1.3 mmol/L) in female [19];

-

Raised BP (antihypertensive drug treatment in a patient with a history of hypertension is an alternate indicator): SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg [19];

-

Raised FPG level (drug treatment of raised glucose is an alternative indicator): ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) [19];

Participants fulfilling at least three out of these five components were diagnosed as having MetS.

Layered approach for blood pressure levels at baseline

Subjects were divided into subgroups according to their BP at entry time using the WHO classification criteria [22]. To avoid the overlap of “optimal pressure” and “normal pressure” in the WHO criteria, we defined optimal pressure as SBP < 120 and DBP < 80 mmHg; normal BP as SBP ≥120 and <130 mmHg, and/or DBP ≥80 and <85 mmHg; high-normal BP as SBP ≥130 and <140 mmHg, and/or DBP ≥85 and <90 mmHg; and high BP as either SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90 mmHg. When a visitor’s SBP and DBP were in different categories, the higher category was used.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as percentages, and continuous data as mean plus standard deviation (SD). The five individual risk factor states were analyzed at baseline and follow-up.

We performed association rule to analyze the changes in MetS component or their combinations during the five-year period in our cohort. As the subjects at baseline were people with two or less MetS components, there were 16 (i.e. ) possible states at baseline, with 32 (i.e. 25) possible states at follow-up. Theoretically, there were 512 (i.e. 16 × 32) possible transitions between states from baseline to follow-up. The data are presented as transitions of states. The module of association rule in SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to generate the change from a risk factor state to another, with “healthy” defined as being the state free of MetS component. Data preparation and descriptive statistics were using the same software.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Capital Medical University of China, and performed in accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki (reference no. 2013SY26).

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Results

At baseline, of the 2,781 subject, 43.7% were mens with the median age of 36.0 years-old (39.0 ± 11.1, mean ± SD), while 56.3% were women with the median age of 39.0 years-old (39.3 ± 10.2). The follow-up interval was 4.83 ± 0.44 years for men and 4.76 ± 0.48 years for women, respectively. To adjust for confounding variables, gender, age, BMI, FPG, SBP, TG and HDL-C at baseline were included in binary logistic regression. The results are shown in Table 1.

The components of MetS in the population at baseline and follow-up were grouped by BP level at baseline (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5). Subjects were divided in two age groups (18–49 and ≥50), which stands for young and old people. The incidence of MetS at follow-up was analyzed by gender and BP level at baseline (Figures 1 and 2). Young men with optimal, normal and high-normal BP had a higher incidence of MetS compared with women in the same groups (23.98% vs. 7.76%, 24.25% vs. 12.84% and 29.20% vs. 22.22%, respectively). The numbers of each gender were almost the same in the high BP group (45.45% vs. 43.08%). Whereas old men with optimal, normal and high-normal BP had a higher incidence of MetS compared with women in the same groups (27.27% vs. 22.22%, 38.64% vs. 31.71, respectively). The numbers of each gender were almost the same in the high-normal and high BP group (27.78% vs. 28.00%, 42.37% vs. 44.74).

The five most common transitions in each subgroup were identified (Figures 3 and 4). As the sample size was too small after grouping by age. The association rule is applied without sub-stratification of age. The support rate of transitions (defined as the percentage of initial state to another state in all possible transitions) was examined in the period 2006/2007 to 2010/2011 in the different subgroups at baseline. For visual simplicity, the five most commonly observed transitions are shown in the parts of the relevant figures. The most common transition in both genders with optimal and normal BP was “healthy” to “healthy”, whereas for the high-normal BP group, the main transition was from “high BP” to “healthy”, and for the group with high BP, the major transition was from “high BP” to “high BP with high fasting glucose”. The rates of transition are shown for each gender and BP group. The confidence rate means how many cases transitioned within a certain status. For example, 244 male subjects were initially healthy at baseline, and 142 (53.79%) of these stayed healthy, while 23 (8.71%) transitioned to hypertension and high fasting glucose at the end of the observation period.

The support and confidence rate of the top five transitions in female subjects from 2006/2007 to 2010/2011 in different blood pressure groups. The support and confidence rate of the top five transitions in male subjects from 2006/2007 to 2010/2011 in different blood pressure groups. (A) in optimal BP group; (B) in normal BP group; (C) in normal-high BP group; (D) in high BP group. Abbreviations: H, health, with the absence of any MetS components; P, high blood pressure; G, high fasting plasma glucose; I, elevated body mass index; T, raised triglycerides level.

The support and confidence rate of the top five transitions in male subjects from 2006/2007 to 2010/2011 in different blood pressure groups. The support and confidence rate of the top five transitions in female subjects from 2006/2007 to 2010/2011 in different blood pressure groups. (A) in optimal BP group; (B) in normal BP group; (C) in normal-high BP group; (D) in high BP group. Abbreviations: H, health, with the absence of any MetS components; P, high blood pressure; G, high fasting plasma glucose; I, elevated body mass index; T, raised triglycerides level.

Discussion

The present cohort study, comprising 2,781 subjects in Beijing Tongren Hospital, focused on detecting how the incidence of MetS changed relative to BP level and what MetS components tend to emerge and change during a 5-year follow-up period. Our study revealed that the higher the BP at baseline, the higher the incidence of MetS at a later stage. We identified that people with different levels of BP would develop different combinations of risk factors. On analyzing the change in risk factors, we found that people with high BP tended to have impaired fasting glucose as the most common additional and new-onset MetS component, and that people with a lower BP level developed raised BP as the initial risk factor of MetS.

SBP and DBP of people with optimal and normal blood pressure at baseline tended to increase with time, while the SBP or DBP dropped in the subjects with high-normal and high blood pressure, according to original Tables 1 and 2. People with high-normal and high blood pressure may be more alert to their health as health education and promotion programs are popular in varies media in Beijing, possible actions could be intentionally or unintentionally taken, and their SBP/ DBP is, therefore, controlled or even lowered.

An association between raised BP and MetS has been reported as the most common MetS component [23], or even serves as an independent predictor for CVD [24]. Several studies with structural equation modeling indicated that hypertension might play both a direct and indirect roles in the development of MetS [25–27]. However, physiologically, it is not easy to connect insulin-resistance with MetS [28]. In the present study, we found that people with optimal and normal BP tended to have a relative lower incidence of MetS after 5 years comparing with people with high BP, and were less susceptible to developing the disorder. Most subjects who started off as “healthy” remained “healthy”, similar to a previous study in a German population [29]. However, abnormal BP tended to be the first risk factor for MetS. About 17% of subjects with high-normal BP returned to “healthy”, while 12% continued to be in the condition.

By analyzing the shifts in MetS components, we found that raised BP was the most common risk factor for all groups. Previous studies have also shown that hypertension was the most important MetS component for men and one of the three most important components for women [30]. Previous study suggested that prehypertension (SBP = 120–139 mmHg, and/or DBP = 80–89 mmHg) was predictive for risk of MetS [31].

In our study, subjects with high BP tended to have impaired fasting plasma glucose as a secondary risk factor. This is accordance with other studies, which found that raised fasting glucose was the second common component of MetS and people with MetS tended to have a disorder of glucose metabolism [32]. Prehypertension may be an end-point related to each of the other four components. It is mainly a consequence of systemic low-grade inflammation and apoA-I dysfunction. In addition to the five components of MetS, prothrombotic and proinflammatory states are essential features based on the evidence of impaired function of HDL and apo A-I particles is discernible by biological evidence of functional defectiveness via outcomes studies and/or correlations with inflammatory and anti-inflammatory biomarkers [33]. The aggregation to lipoprotein (Lp)(a) of apolipoprotein (apo) A-I underlies HDL dysfunction, and is an independent risk factor of magnitude similar to conventional components of MetS [34]. Some studies indicated that proinflammatory state and oxidative stress are crucial for cardiometabolic disorders. Factors such as creatinine, platelet-activating factor, acetylhydrolase, thyroid stimulating hormone, acylation-stimulating protein, asymmetric dimethylarginine, and serum lipoprotein (Lp) (a) are key to trigger systemic low-grade inflammation and enhanced autoimmune reactions, which may induce impaired glucose and metabolic syndrome [35].

In most circumstances, “healthy” was the predominant state, and people with a single risk factor tended to return to the “healthy” state. High-normal BP was a crucial status for MetS prevention. As hypertension has a low rate of awareness in China, it is an important preventable risk factor for MetS and CVD events [36].

The strengths of this research were that it was a longitudinal study of 5 years in a Chinese population with data of relatively good quality. The limitation was the lack of waist circumference as an indicator for central obesity; however, we used BMI for substitute according to the WHO expert consultation [21]. As Tongren Hospital is located in the center of Beijing, bias may be that there were more people with an urban life style recruited for the research. In addition, this study was based on a population attending for routine health check-up. Further studies using the general population would be desirable.

Conclusions

The incidence of MetS augments with the elevation of BP over time. People with optimal and normal BP were less susceptible than people with higher BP to developing MetS. Although most cases stayed “healthy”, they tended to have abnormal BP as the initial sign of MetS. High-normal BP was a crucial status for MetS prevention as some of the cases were able to return “healthy”. In the high BP group, high fasting glucose was a secondary risk factor. More efforts are needed to identify effective intervention for individuals with abnormal BP to prevent those developing MetS.

References

Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J: The metabolic syndrome–a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005, 366 (9491): 1059-1062. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8.

Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J: Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006, 23 (5): 469-480. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x.

Cameron AJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ: The metabolic syndrome: prevalence in worldwide populations. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2004, 33 (2): 351-375. 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.03.005. table of contents

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001, 285 (19): 2486-2497. 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, et al: Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart association/national heart, lung, and blood institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005, 112 (17): 2735-2752. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404.

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002, 106 (25): 3143-3421.

Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ: The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9468): 1415-1428. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7.

Eberly LE, Prineas R, Cohen JD, Vazquez G, Zhi X, Neaton JD, Kuller LH: Metabolic syndrome: risk factor distribution and 18-year mortality in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Diabetes care. 2006, 29 (1): 123-130. 10.2337/diacare.29.01.06.dc05-1320.

McNeill AM, Katz R, Girman CJ, Rosamond WD, Wagenknecht LE, Barzilay JI, Tracy RP, Savage PJ, Jackson SA: Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in older people: the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006, 54 (9): 1317-1324. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00862.x.

Marroquin OC, Kip KE, Kelley DE, Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Sharaf BL, Pepine CJ, Sopko G, Reis SE: Metabolic syndrome modifies the cardiovascular risk associated with angiographic coronary artery disease in women: a report from the women’s Ischemia syndrome evaluation. Circulation. 2004, 109 (6): 714-721. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115517.26897.A7.

Mitka M: Does the metabolic syndrome really exist? Diabetes and heart disease groups spar over issue. JAMA. 2005, 294 (16): 2010-2013. 10.1001/jama.294.16.2010.

Borch-Johnsen K, Wareham N: The rise and fall of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 2010, 53 (4): 597-599. 10.1007/s00125-010-1659-2.

Gale EA: The myth of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 2005, 48 (9): 1679-1683. 10.1007/s00125-005-1873-5.

Tseng LN, Tseng YH, Jiang YD, Chang CH, Chung CH, Lin BJ, Chuang LM, Tai TY, Sheu WH: Prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidemia and their associations with micro- and macrovascular diseases in patients with diabetes in Taiwan: an analysis of nationwide data for 2000–2009. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012, 111 (11): 625-636. 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.09.010.

Franco OH, Massaro JM, Civil J, Cobain MR, O’Malley B, D’Agostino RB: Trajectories of entering the metabolic syndrome: the framingham heart study. Circulation. 2009, 120 (20): 1943-1950. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.855817.

Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru M, Usala G, Piras MG, Ferrucci L, Cao A, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Lakatta EG: The central arterial burden of the metabolic syndrome is similar in men and women: the SardiNIA study. Eur Heart J. 2010, 31 (5): 602-613. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp491.

Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Lakatta EG: Arterial aging: is it an immutable cardiovascular risk factor?. Hypertension. 2005, 46 (3): 454-462. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000177474.06749.98.

Scuteri A, Morrell CH, Najjar SS, Muller D, Andres R, Ferrucci L, Lakatta EG: Longitudinal paths to the metabolic syndrome: can the incidence of the metabolic syndrome be predicted? The Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009, 64 (5): 590-598.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC: Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009, 120 (16): 1640-1645. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644.

Feng RN, Zhao C, Wang C, Niu YC, Li K, Guo FC, Li ST, Sun CH, Li Y: BMI is strongly associated with hypertension, and waist circumference is strongly associated with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia, in northern Chinese adults. J Epidemiol. 2012, 22 (4): 317-323. 10.2188/jea.JE20110120.

WHO Expert Consultation: Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004, 363 (9403): 157-163.

Chalmers J, MacMahon S, Mancia G, Whitworth J, Beilin L, Hansson L, Neal B, Rodgers A, Ni Mhurchu C, Clark T: World health organization-international society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the world health organization. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1999, 21 (5–6): 1009-1060.

Chimonas T, Karagiannis A, Athyros VG, Achimastos A, Elisaf M, Panagiotakos DB: Blood pressure levels constitute the most important determinant of the metabolic syndrome in a Mediterranean population: a discrimination analysis. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010, 8 (6): 523-529. 10.1089/met.2010.0023.

Foucan L, Deloumeaux J, Donnet JP, Bangou J, Larifla L, Messerchmitt C, Salmi LR, Kangambega P: Metabolic syndrome components in Indian migrants with type 2 diabetes: a matched comparative study. Diabetes Metab. 2006, 32 (4): 337-342. 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70288-4.

Shen BJ, Todaro JF, Niaura R, McCaffery JM, Zhang J, Spiro A, Ward KD: Are metabolic risk factors one unified syndrome? Modeling the structure of the metabolic syndrome X. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 157 (8): 701-711. 10.1093/aje/kwg045.

Ferguson TF, Funkhouser E, Roseman J: Factor analysis of metabolic syndrome components in the coronary artery risk Development in young adults (CARDIA) study: examination of factors by race-sex groups and across time. Ann Epidemiol. 2010, 20 (3): 194-200. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.11.002.

Shen BJ, Goldberg RB, Llabre MM, Schneiderman N: Is the factor structure of the metabolic syndrome comparable between men and women and across three ethnic groups: the Miami community health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006, 16 (2): 131-137. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.049.

Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW: Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and incident cardiovascular events in the Framingham offspring study. Diabetes. 2005, 54 (11): 3252-3257. 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3252.

Haring R, Rosvall M, Volker U, Volzke H, Kroemer H, Nauck M, Wallaschofski H: A network-based approach to visualize prevalence and progression of metabolic syndrome components. PloS one. 2012, 7 (6): e39461-10.1371/journal.pone.0039461.

Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH: Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among u.s. Adults. Diabetes care. 2004, 27 (10): 2444-2449. 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444.

Onat A, Yazici M, Can G, Kaya Z, Bulur S, Hergenc G: Predictive value of prehypertension for metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and coronary heart disease among Turks. Am J Hypertens. 2008, 21 (8): 890-895. 10.1038/ajh.2008.212.

Liese AD, Mayer-Davis EJ, Haffner SM: Development of the multiple metabolic syndrome: an epidemiologic perspective. Epidemiol Rev. 1998, 20 (2): 157-172. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017978.

Onat A: Metabolic syndrome: nature, therapeutic solutions and options. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011, 12 (12): 1887-1900. 10.1517/14656566.2011.585462.

Onat A, Can G, Murat S, Cicek G, Ornek E, Yuksel H: Aggregation of lipoprotein (a) to apolipoprotein A-I underlying HDL dysfunction as a major coronary risk factor. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2013, 13: 543-551.

Onat A, Can G: Enhanced proinflammatory state and autoimmune activation: a breakthrough to understanding chronic diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2013, [Epub ahead of print]

Gu D, Gupta A, Muntner P, Hu S, Duan X, Chen J, Reynolds RF, Whelton PK, He J: Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor clustering among the adult population of China: results from the international collaborative study of cardiovascular disease in Asia (InterAsia). Circulation. 2005, 112 (5): 658-665. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.515072.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/912/prepub

Acknowledgements

Funding: Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Serial Number: 7131002); Key Projects in the National Science & Technology Pillar Program in the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period of China (Serial Number: 2011BAI08B01); The Program of Natural Science Fund of China (Serial Number: 81373099); Funding Project for Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Serial Number: 7122016)

All funding sources were independent and had no influence on the study design; the collection, analyses, and interpretation of our data; the writing of this report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DH, LT, XL, and WW contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the article, critical revision of the article, and statistical analysis; ZW, DC and XG contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, field investigation and quality control; DH, LT, XY, YL and XG contributed to the drafting of the article, and critical revision of the article; XG had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors gave their final approval for the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Huo, D., Tao, L., Li, X. et al. Association of blood pressure with development of metabolic syndrome components: a five-year Retrospective Cohort study in Beijing. BMC Public Health 13, 912 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-912

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-912