Abstract

Background

Hospitalization for heart failure (HF) is associated with high-in-hospital and short- and long-term post discharge mortality. Age and gender are important predictors of mortality in hospitalized HF patients. However, studies assessing short- and long-term risk of death stratified by age and gender are scarce.

Methods

A nationwide cohort was identified (ICD-9 codes 402, 428) and followed through linkage of national registries. The crude 28-day, 1-year and 5-year mortality was computed by age and gender. Cox regression models were used for each period to study sex differences adjusting for potential confounders (age and comorbidities).

Results

14,529 men, mean age 74 ± 11 years and 14,524 women, mean age 78 ± 11 years were identified. Mortality risk after admission for HF increased with age and the risk of death was higher among men than women. Hazard ratio's (men versus women and adjusted for age and co-morbidity) were 1.21 (95%CI 1.14 to 1.28), 1.26 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.31), and 1.28 (95%CI 1.24 to 1.31) for 28 days, 1 year and 5 years mortality, respectively.

Conclusions

This study clearly shows age- and gender differences in short- and long-term risk of death after first hospitalization for HF with men having higher short- and long-term risk of death than women. As our study population includes both men and women from all ages, the estimates we provide maybe a good reflection of 'daily practice' risk of death and therefore be valuable for clinicians and policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Heart failure (HF) is a significant and growing health problem, because of the combination of an ageing population and more effective treatment of its major precursor, myocardial infarction [1]. The prevalence of heart failure, a dominant cause of hospitalization in men and women > 65 years in Western population, is estimated to increase from 0.7% for those 45 to 54 years of age to 8.4% for those aged 75 years or older [2].

Current models that are used for the evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and impact on outcomes of heart failure management programmes or predicting the burden on the health care system use overall mortality risks extracted from studies without detailed information on gender- and age-specific mortality or assumptions concerning death rates are made [3–5]. However, age and gender appear to be important predictors of mortality in hospitalized HF patients [6].

Studies presenting short- and long-term mortality risks stratified by age and gender are scarce. Most available studies present the impact of age and gender on mortality using relative risks or hazard ratios, without providing stratified and detailed mortality risks for age and gender subgroups [6–8]. Some studies reported stratified mortality risks, but these were mostly limited to either age or gender [9–12]. Two studies were identified that reported stratified mortality risks by age and gender [13, 14]. However, these studies were restricted to short-term risk of death. Only one study could be identified that presented both short- and long-term risk of death stratified by age and gender [10]. However, this study did not include patients from all ages. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to estimate detailed short- and long-term mortality risks stratified by age and gender in a large nationwide cohort of patients first hospitalized for HF, including both men and women from all ages.

Methods

For the present study, cohorts were drawn from 1997 and 2000. The choice of these two years was based on pragmatic reasons at the time of the initiation of the project in 2001. The total population of the Netherlands in 1997 and 2000 was 15,567,107 (men 7,696,803, women 7,870,304) and 15,863,950 (men: 7,846,317, women: 8,017, 633), respectively. Approximately 14% of the population was older than 65 years. To construct a cohort of patients admitted for the first time because of HF, information from the national Hospital Discharge Registry (HDR) and the Dutch Population Registry (PR) were linked. Information on cause of death was derived from the Cause of Death Registry of Statistics Netherlands. The registries (which are partly openly available) and linkage procedures have been previously described in detail [15]. In brief, the HDR is a database on admissions, not persons. For each hospital admission a new record is created in the HDR. Following individuals over time based on HDR-information alone is troublesome due to difficulties in identification of different admissions from the same person in time and admissions for the same condition at another hospital (due to referral or to address changes). Yet, linkage (linkage variables date of birth, gender and 4 digits of postal code) with the PR can overcome these issues.

Study population

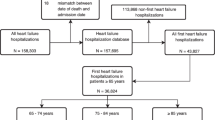

All hospital admissions for HF (ICD-9-CM code 402, 428) between January 1st and December 31st, 1997 and January 1st and December 31st, 2000, were selected from the HDR (which was previously linked with PR). There were 43,738 hospital admissions. In case of multiple HF admissions for an individual within the same year we only used the first admission, yielding a total of 37,386 heart failure patients. Subsequently, information was collected on hospital admission that may have occurred previously (1995-1997 (data earlier than 1995 were not available since linkage with PR is only possible from 1995 onwards) and 1995-2000, respectively) for the same condition. Those with a previous admission for heart failure were excluded (n = 8,333). This resulted in a cohort consisting of 29,053 patients with a first hospitalization for heart failure in 1997 or 2000 in the Netherlands.

Co-morbidity

The presence of co-morbidity (cardiovascular disease (ICD-9-CM codes 390-459) or diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250)) was determined on the basis of the discharge diagnosis of previous hospital admissions or on the basis of a secondary diagnosis at the moment of the index admission. No information on severity of disease, risk factors (hypertension, smoking) or medication use was available in the registry.

Follow-up

Information on mortality of the patients was obtained by linkage of the cohort with national Cause of Death Register. Linkage of the PR (with which the HDR cohort was previously linked) with the Cause of Death Register (Statistics Netherlands) was performed using a unique identification key and therefore was almost complete. Patients were censored if they migrated out of the Netherlands or if their linkage key was not unique anymore during follow-up. Death was coded using the tenth revision of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10).

Data analysis

We analyzed mortality from all causes by examining the proportion of patients that died within 28-days, 1-year, and 5-years after their first admission for heart failure.

Survival time was calculated as the time from the initial admission date in 1997 or 2000 for HF to the date of death from any cause or to the date that a patient was censored, which ever came first. The crude short-term (28 day), 1 year and long-term (5-year) mortality was computed by age and gender according to the actuarial life table method and expressed as percentages. The mortality rate in men was compared to mortality rate in women by calculating relative risks (with 95% CI). Cox regression models were used for each period to study differences between men and women in their risk of death with and without adjusting for potential confounders (age and previous admissions for cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus). Data were analyzed with SPSS software, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). All analyses were performed in agreement with privacy legislation in the Netherlands [16].

Results

A total of 29,053 patients (mean age 76 ± 11) with a first hospitalization for congestive heart failure in 1997 or 2000 were identified. General characteristics are provided in Table 1. Eighteen, 38% and 67% of all men and 27%, 36% and 66% of all women died within 28 days, 1-year and 5 years, respectively.

Cause of death

Cardiovascular disease was the most frequent cause of death at 28-days, 1-year and 5-year (table 2). The contribution of cardiovascular diseases as cause of death decreased with increasing follow-up time while the contribution of cancer as a cause of death increased.

28 day mortality

Short term mortality risk increased with age in men and women (from 7.5% in men younger than 55 years to 32.9% in men older than 85 years and from 6.9% in women younger than 55 years to 27.2% in women older than 85 years). Higher mortality rates in men compared to women were found across all ages above 65 years (Table 3). Crude overall mortality was similar for men and women (hazard ratio 0.99; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.05). However, after adjustment for potential confounders (age, previous admission for cardiovascular diseases or diabetes mellitus) mortality was higher in men than in women (hazard ratio 1.21; 95% CI 1.14 to 1.28) (Table 4).

One-year mortality

One-year mortality risk increased with age in men and women (from 17.2% in men younger than 55 years to 58.6% in men older than 85 years and from 14.9% in women younger than 55 years to 49.9% in women older than 85 years). One-year mortality was higher in men than in women across all ages above 65 years (Table 3). The crude overall mortality was similar for men and women at 1 year (hazard ratio 1.04; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.08). However, after adjustment for potential confounders mortality was higher for men compared to women (Table 4).

Five-year mortality

Five-year mortality risk increased with age in men and women (from 34.2% in men younger than 55 years to 87.1% in men older than 85 years and from 27.6% in women younger than 55 years to 84.1% in women older than 85 years). A higher mortality in men compared to women was found across all ages; but this difference was not statistically significant for men and women between 60 and 64 years (Table 3). After adjustment for potential confounders overall five-year mortality was higher for men compared to women (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study using a nationwide cohort of 29,053 patients first hospitalized for heart failure shows clear age- and gender differences in short- and long-term mortality risk.

We describe a high mortality over a follow-up of 5 years with men having a higher short- and long-term risk of death than women.

Overall mortality risks are presented in several population based cohort studies and in intervention studies evaluating the effect of drug treatment in HF. Similar overall short- and long-term mortality risks were presented in population based cohorts [17, 18]. The ARIC study [19] however, reported lower short- and long-term mortality risk. Though patients were considerable younger in the ARIC study (mean age 57 years versus 76 years). Trials [20–23] also report lower mortality risks (1-year mortality risks ranged from 8 to 31% compared to 37%). This likely reflects the younger age and less co-morbidity of patients participating in trials evaluating the effect of drug treatment for HF [24–26].

The limited available age- and gender specific data show that the Swedish short-term mortality risks were lower, the Scottish short- and long-term mortality risks were higher [10], whereas in the United States 30-day mortality risks were lower while 1-year mortality risks were similar [13]. The differences in mortality risk between the countries might reflect differences in health care system and treatment as well as differences in patient characteristics. The latter however remains a matter of speculation since we had no information about the medication prescribed and limited information on clinical characteristics of the patients.

The higher mortality risks in men compared to women reported in this study have also been reported in previous large epidemiological studies [27]. A better long-term survival after 10-15 years has been reported in women across all age groups [28]. In contrast to these studies, survival was higher in men than in women in the SOLVD trial [29]. In studies of patients admitted to hospital, women were found to have a lower [13, 30] or equal mortality [9]. Possible explanations for the association between gender and mortality risk that have been reported include that men are more likely than women to have an ischemic etiology of their heart failure and that ventricular ejection fraction is higher in female than in male heart failure patients with a nonischemic cause [30].

Our results provide insight in age-and gender-specific risk of death following initial admission for heart failure. As our study population includes both men and women from all ages, the estimates we provide maybe a good reflection of 'daily practice' risk of death and therefore be valuable for clinicians and policymakers. Furthermore, these results can be used for the evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and impact on outcomes of heart failure management programmes that focuses on secondary prevention.

The strength of our study is the large size of the cohort obtained from usual care with a large age range and information on both men and women. Even though the validity of national registries has been questioned, several studies have shown that for the Netherlands, the validity is adequate [31]. Positive predictive values for the use of ICD-9 code 428 to identify patients with HF varies between 80.0% [32] and 94.3% [33]. The quality of the applied linkage strategy has been excellent [31]. The cause of death information used in our study was not validated by medical records or autopsy. As a result, the degree of misclassification in the cause of death is unquantifiable. However, as in almost every study using data from vital statistics, some degree of misclassification is inevitable. In addition, the validity of the Dutch national Cause of Death registry has been reported to be higher than the average validity of eight countries in the European Community [34].

To appreciate the findings of this study the following issues needs consideration. The search for previous admissions to maximum of 6 years before, might have led to that some "first" heart failure patients were actually recurrent heart failure patients. The risk of recurrence is the highest within the first two years (44% readmission within 6 months [35] and 70% readmission within 2 years after a first admission for heart failure [36]). The inclusion of recurrent heart failure patients may cause overestimation of absolute mortality rates (as recurrent heart failure patients may be more severe who are likely to have a higher mortality risk) but its extent is difficult to quantify.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study clearly shows age- and gender differences in short- and long-term risk of death after first hospitalization for heart failure with men having a higher short- and long-term risk of death than women. As our study population includes both men and women from all ages, the estimates we provide maybe a good reflection of 'daily practice' risk of death and therefore be valuable for clinicians and policymakers.

References

Mosterd A, Hoes AW: Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. 2007, 93: 1137-1146. 10.1136/hrt.2003.025270.

Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ: Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003, 289: 194-202. 10.1001/jama.289.2.194.

Bilcke J, Van Damme P, De Smet F, Hanquet G, Van Ranst M, Beutels P: The health and economic burden of rotavirus disease in Belgium. Eur J Pediatr. 2008, 67: 1409-1419. 10.1007/s00431-008-0684-3.

Collins SP, Schauer DP, Gupta A, Brunner H, Storrow AB, Eckman MH: Cost-effectiveness analysis of ED decision making in patients with non-high-risk heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2009, 27: 293-302. 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.02.025.

Miller G, Randolph S, Forkner E, Smith B, Galbreath AD: Long-Term Cost-Effectiveness of Disease Management in Systolic Heart Failure. Med Decis Making. 2009, 29: 325-33. 10.1177/0272989X08327494.

Velavan P, Khan NK, Goode K, Rigby AS, Loh PH, Komajda M, Follath F, Swedberg K, Madeira H, Cleland JG: Predictors of short term mortality in heart failure - Insights from the Euro Heart Failure survey. Int J Cardiol. 2010, 138: 63-69. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.004.

Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, Skali H, McMurray JJ, Granger CB, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Young JB, Michelson EL, Pfeffer MA: Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007, 116: 1482-1487. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696906.

Tribouilloy C, Buiciuc O, Rusinaru D, Malaquin D, Levy F, Peltier M: Long-term outcome after a first episode of heart failure. A prospective 7-year study. Int J Cardiol. 2010, 140: 309-14. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.087.

Galvao M, Kalman J, DeMarco T, Fonarow GC, Galvin C, Ghali JK, Moskowitz RM: Gender differences in in-hospital management and outcomes in patients with decompensated heart failure: analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). J Card Fail. 2006, 12: 100-107. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.09.005.

Jhund PS, Macintyre K, Simpson CR, Lewsey JD, Stewart S, Redpath A, Chalmers JW, Capewell S, McMurray JJ: Long-term trends in first hospitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation. 2009, 119: 515-523. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812172.

Shafazand M, Schaufelberger M, Lappas G, Swedberg K, Rosengren A: Survival trends in men and women with heart failure of ischaemic and non-ischaemic origin: data for the period 1987-2003 from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Registry. Eur Heart J. 2009, 30: 671-678. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn541.

Stewart S, Macintyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJ: More 'malignant' than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001, 3: 315-322. 10.1016/S1388-9842(00)00141-0.

Rathore SS, Foody JM, Wang Y, Herrin J, Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM: Sex, quality of care, and outcomes of elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the National Heart Failure Project. Am Heart J. 2005, 149: 121-128. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.06.008.

Schaufelberger M, Swedberg K, Koster M, Rosen M, Rosengren A: Decreasing one-year mortality and hospitalization rates for heart failure in Sweden; Data from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Registry 1988 to 2000. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25: 300-307. 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.012.

Agyemang C, Vaartjes I, Bots ML, Valkengoed van I, de Munter JS, de Bruin A, Berger-van SM, Reitsma JB, Stronks K: Risk of death after first admission for cardiovascular diseases by country of birth in The Netherlands: a nationwide record-linked retrospective cohort study. Heart. 2009, 95: 747-753. 10.1136/hrt.2008.159285.

Reitsma JB, Kardaun JW, Gevers E, de Bruin A, van der Wal J, Bonsel GJ: Possibilities for anonymous follow-up studies of patients in Dutch national medical registrations using the Municipal Population Register: a pilot study. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003, 147: 2286-2290.

Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ, Thompson SG, Suresh V, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC: Survival of patients with a new diagnosis of heart failure: a population based study. Heart. 2000, 83: 505-510. 10.1136/heart.83.5.505.

Krumholz HM, Butler J, Miller J, Vaccarino V, Williams CS, Mendes de Leon CF, Seeman TE, Kasl SV, Berkman LF: Prognostic importance of emotional support for elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation. 1998, 97: 958-964.

Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE: Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol. 2008, 101: 1016-1022. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061.

Blair JE, Zannad F, Konstam MA, Cook T, Traver B, Burnett JC, Grinfeld L, Krasa H, Maggioni AP, Orlandi C, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zimmer C, Gheorghiade M: Continental differences in clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with worsening heart failure results from the EVEREST (Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure: Outcome Study with Tolvaptan) program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52: 1640-1648. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.056.

Ghali JK, Krause-Steinrauf HJ, Adams KF, Khan SS, Rosenberg YD, Yancy CW, Young JB, Goldman S, Peberdy MA, Lindenfeld J: Gender differences in advanced heart failure: insights from the BEST study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 42: 2128-2134. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.05.012.

O'Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB, McMurray JJ, Pina IL, Granger CB, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Solomon SD, Pocock S, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA: Sex differences in clinical characteristics and prognosis in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: results of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Circulation. 2007, 115: 3111-3120. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.673442.

Ritter M, Laule-Kilian K, Klima T, Christ A, Christ M, Perruchoud A, Mueller C: Gender differences in acute congestive heart failure. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006, 136: 311-317.

Cowie MR, Mosterd A, Wood DA, Deckers JW, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC, Grobbee DE: The epidemiology of heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1997, 18: 208-225.

Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D: The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993, 22: 6A-13A. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90455-A.

Lloyd-Williams F, Mair F, Shiels C, Hanratty B, Goldstein P, Beaton S, Capewell S, Lye M, Mcdonald R, Roberts C, Connelly D: Why are patients in clinical trials of heart failure not like those we see in everyday practice?. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003, 56: 1157-1162. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00205-1.

Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Grossman W, Levy D: Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham Heart Study subjects. Circulation. 1993, 88: 107-115.

Schocken DD, Arrieta MI, Leaverton PE, Ross EA: Prevalence and mortality rate of congestive heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992, 20: 301-306. 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90094-4.

Bourassa MG, Gurne O, Bangdiwala SI, Ghali JK, Young JB, Rousseau M, Johnstone DE, Yusuf S: Natural history and patterns of current practice in heart failure. The Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Investigators. J. Am Coll Cardiol. 1993, 22: 14A-19A. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90456-B.

Adams KF, Dunlap SH, Sueta CA, Clarke SW, Patterson JH, Blauwet MB, Jensen LR, Tomasko L, Koch G: Relation between gender, etiology and survival in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996, 28: 1781-1788. 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00380-4.

Paas GRA, Veenhuizen KCW: Research on the validity of the LMR [In Dutch]. 2002, Prismant: Utrecht

Merry AH, Boer JM, Schouten LJ, Feskens EJ, Verschuren WM, Gorgels AP, van den Brandt PA: Validity of coronary heart diseases and heart failure based on hospital discharge and mortality data in the Netherlands using the cardiovascular registry Maastricht cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009, 24: 237-247. 10.1007/s10654-009-9335-x.

Lee DS, Donovan L, Austin PC, Gong Y, Liu PP, Rouleau JL, Tu JV: Comparison of coding of heart failure and comorbidities in administrative and clinical data for use in outcomes research. Med Care. 2005, 43: 182-188. 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00012.

Mackenbach JP, van Duyne WM, Kelson MC: Certification and coding of two underlying causes of death in The Netherlands and other countries of the European Community. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987, 41: 156-160. 10.1136/jech.41.2.156.

Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, Vaccarino V, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Hennen J: Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997, 157: 99-104. 10.1001/archinte.157.1.99.

Luthi JC, Lund MJ, Sampietro-Colom L, Kleinbaum DG, Ballard DJ, McClellan WM: Readmissions and the quality of care in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003, 15: 413-421. 10.1093/intqhc/mzg055.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/637/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant of the project 'Cardiovascular disease in the Netherlands figures and facts').

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

IV performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. AH conceived of the study and commented the draft. JR participated in the design of this study and commented the draft. AB participated in the design of this study and commented the draft. DG conceived of the study and commented the draft. AM conceived of the study and commented the draft. MB conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaartjes, I., Hoes, A., Reitsma, J. et al. Age- and gender-specific risk of death after first hospitalization for heart failure. BMC Public Health 10, 637 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-637

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-637